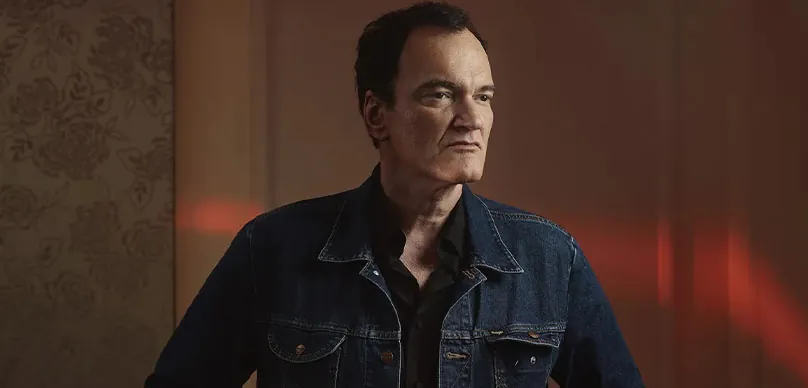

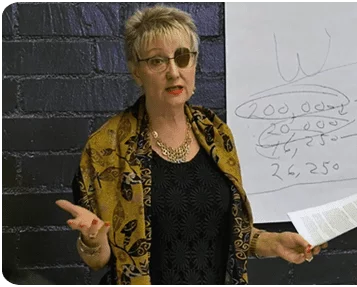

The story of cinema is often the story of unlikely beginnings. On today’s episode, we welcome Dale Sherman, an author who began his career chronicling the world of rock music before turning his attention to one of the most distinctive filmmakers of our time—Quentin Tarantino. Best known for his books on Kiss and Alice Cooper, Dale’s latest work, The Quentin Tarantino FAQ, is a deep dive into the life, craft, and legacy of the director who reshaped independent film.

Dale’s own path mirrors the persistence required of any filmmaker. In the early ’80s, he was part of a fan magazine scene, writing and producing work at a time when exposure was rare and self-publishing meant Xerox machines and stapled pages. That grassroots hustle translated into authorship, and eventually, into a fascination with film. When deciding on his next subject, Dale saw Tarantino as a perfect study: “People know his films, but they don’t know the man.” For filmmakers, this book offers not only behind-the-scenes anecdotes but also a map of how vision, persistence, and timing can converge to launch a career.

Dale walks us through Tarantino’s early days—stories of odd jobs, unfinished projects, and his first attempt at a feature, My Best Friend’s Birthday. Though the film collapsed in execution, Dale emphasizes how even failure provided Tarantino with a kind of rehearsal for the industry. “You look at his early script and you think, this really works,” Dale notes, underscoring that the DNA of Tarantino’s later brilliance was already present. For filmmakers, it’s a reminder that abandoned projects and rough first drafts are not wasted—they’re training grounds.

The turning point came with screenplays like True Romance and Natural Born Killers, born from an earlier script titled The Open Road. These works not only earned him recognition but also the financial means to pursue Reservoir Dogs. Initially envisioned as a $50,000 black-and-white project starring his friends, the film exploded into something much larger after Harvey Keitel came onboard. Filmmakers will recognize this pivot: the moment when a small independent vision suddenly attracts momentum and becomes a cultural event.

Dale’s book also examines Tarantino’s evolution through films like Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown, Kill Bill, and beyond. He explores how Tarantino developed signature techniques: weaving pop culture references into dialogue, using music as an almost narrative force, and structuring non-linear stories that challenged Hollywood norms. For directors and writers, these insights are valuable lessons in how a personal voice can both shape and disrupt an industry.

No discussion of Tarantino is complete without controversy. Dale doesn’t avoid debates around violence, language, or Tarantino’s own cameos. Filmmakers may find inspiration in how Tarantino navigates criticism. As Dale points out, Tarantino faces questions about violence or offensive dialogue with the same persistence he faced rejection in his early years. Rather than retreat, he continues to double down on authenticity, even when it divides audiences.

What makes Dale’s book stand out is the depth of research. Instead of relying solely on retrospective interviews, he digs into contemporary articles and early reactions, contrasting them with later reinterpretations. For filmmakers, this approach is a lesson in the importance of context—understanding how a work is received in its moment and how that reception changes over time. It also reflects the reality of any creative career: today’s controversy can become tomorrow’s milestone.

In the end, Dale Sherman’s exploration of Tarantino is more than biography—it’s a case study in independent filmmaking, artistic persistence, and the messy but vital process of creating work that endures. For filmmakers navigating their own uncertain paths, the story of a video store clerk who transformed cinema serves as both cautionary tale and inspiration.