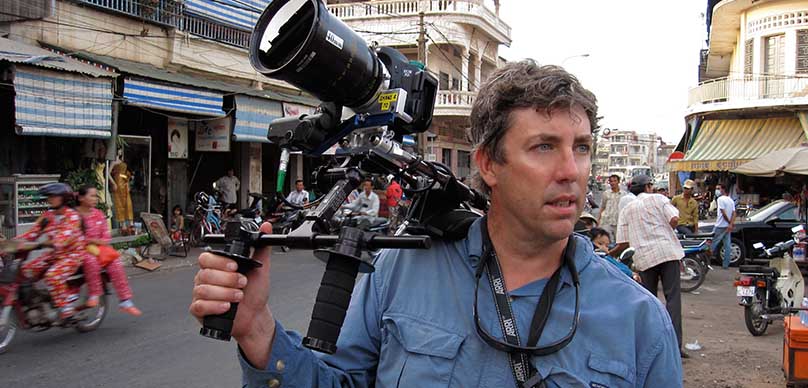

Pat McGowan is a longtime Film & Video Creator from Ottawa, Canada. As with many in the “biz”, his career started as a musician, moved into audio post and then into directing, producing, shooting and editing. Until recently Pat was the owner/operator of inMotion.ca, a video production company in Ottawa & Toronto. Pat has a passion for wildlife videography and can be found in the Canadian Arctic looking for Polar bears, Narwhals, and Bowhead Whales.

After a successful career spanning over two decades, Pat had an epiphany, and that led to the idea and creation of BlackBox Global. He wants nothing less than to change the relationships that creators have with each other and the global market so they can have better lives. He invites his fellow film & video peeps to join BlackBox and make the world a place where creators can be free to do what they love, own the content they make, and be fairly compensated.

Alex Ferrari 1:44

Enjoy today's episode with guest host Dave Bullis.

Dave Bullis 1:48

My next guest is a filmer videographer from Ottawa, Canada, he has been in the business for years making different wildlife videos. And he likes to talk a lot about videography, doing interviews, even like this. You know, what happens when somebody you know, you do a project and somebody says, Hey, Mike, get my kid to make this for cheaper? Why am I paying you $10,000 or $5,000, I can get my kid to do it with an iPhone, we talk all about that stuff, which happens a lot nowadays, which is one of the reasons why I don't do it anymore. Because it just got, it just got such a pain in the ass. Because if your kid can do it, why the hell you've been talking to me. And I took a little bit of some stories in this tool about some of the things that I've encountered. And we're going to talk about black box, which is what my next guest decided to make. And it's a really, really cool venture. So without further ado, Pat McGowan.

Pat McGowan 2:36

I was always a kid that was interested in a lot of different things that I think I was pretty visual, but I was more on the audio side, I was a musician. I was interested in the music business, I worked as a musician for a long time, but I also had my scientific side. So I ended up doing like pre meds and biology and psychology at college. And, and I was a photographer when I was a kid. So I was just kind of this mishmash, mixed up kid didn't know what I wanted to do. But I had an opportunity when I was in college to join a rock band and, and do some studio work. And when I walked into the actual recording studio was a 16 track recording studio in Toronto. And I'll never forget the feeling that I was home. So I was really, I was a studio guy. And that led me into film as a composer and as an audio post guy, and then led me into more as a director. And, you know, it's kind of best of all worlds for me.

Dave Bullis 3:40

So but you know, the viewer will always very interest interests, they usually end up making the most interesting people.

Pat McGowan 3:46

Well, I'm not gonna say that maybe you can, at the end of the interview, let's see what you have to say then.

Dave Bullis 3:52

All right. All right. Now now the pressure is on Pat. Now it has to be interesting. So basically, when you were going to college, you know, and you were just doing all these different things. I kind of sounds like my route to because you know, when I was going to college, yeah, I was doing 10,000 different things. But I was always the one thing I was study was screenwriting and stuff like that. And by the time I was ready to graduate, I was like, I don't want to do this one thing anymore, which was business. I was like, I don't want to go in that anymore. I'm about to get a degree in it. What the hell?

Pat McGowan 4:20

I hear you, man. Absolutely. We're really lucky to do what we do. You know, because we get to be involved in so many different things in so many different aspects of life. We get to travel we get to meet a lot of people. You know, in my in my corporate and government and and film production life. I was on a new subject matter every week or two, you know, and you had to become an instant expert, and you had to be able to hold your own. Especially if you're interviewing people like you do. And, you know, it's just been a wonderful ride.

Dave Bullis 4:58

Yeah, interviewing people. I I, you know, just as a side of this podcast has really helped me in other ways, too. It's only made me a better conversationalist. But it's just, you know, you can you can put it out, and I'll talk to anybody. I mean, I was always pretty good before at networking. But I think this is maybe from like, good to, like, great, because now you could just be you have the confidence just to go up and strike a conversation about anything. Yeah,

Pat McGowan 5:20

for sure. Man, you just have to ask two or three questions and, and know people, people love to talk about themselves and what they do. And if you just get out of their way, normally, normally, you'll get some gold. Yeah,

Dave Bullis 5:33

very, very true. That's why I tend to let people just sort of the look, the guests take that take over the conversation, because a lot of times, they might my guests will say, Oh, my God, I just was talking, talking and talking. And I said, Well, that's a good thing. Because because I'm here every week, you know, I go, the guest is only here for the one time, so I might as well you know, showcase them?

Pat McGowan 5:53

Well, once you get me going, you're not going to shut me up that easily.

Dave Bullis 5:58

Yeah, I always say feel free to talk as much as you want. And I will edit it and make it look better. Anything. All

Pat McGowan 6:03

right. Sounds good to me, man.

Dave Bullis 6:05

So so when you're going out there, and you're doing like freelance video, videography work and stuff like that, and you do a commercial work, and etc. What are some of the things that you learned, or some of the tips that you could like, give because I, you know, I had a friend of mine, for instance, he always would go into like different stores, like like mom and pop stores and pizza places and stuff. And he'd always, you know, say to the owner, hey, this is a really cool place. You know, this is a really cool, blah, blah. And he always would try to, you know, different locations, he always would keep in the back of his mind, in case you ever had to film there for whatever reason, you know, have you ever do you have any tips like that about how you you'll maybe get, you know, maybe met different people at different places?

Pat McGowan 6:46

Yeah, no question about that, especially because of some of the work that I do. And a lot of the work that I ended up doing had to do with filming, you know, B roll on stock footage. So you're always on the lookout for friendly people that can give you access, you're always on the lookout for great locations that you can return to later. So yeah, you just really keep your eyes peeled, and, and, you know, figure it out. And if you end up doing, you know, a TV series, or whatever you kind of got, you know, in my case, I'm Canadian, and I've got Canada mapped. I've been all over the country, I've been all in every single province, I've been in every single city. And we know a lot of people. And you know, the thing is, is that we're all kind of connected now. So once you make those relationships, and you understand the mapping, then it's so much easier to go back. And the next time you're there, you kind of know where you are. And yeah, so you just kind of keep your eyes peeled and and develop the relationships as you move along.

Dave Bullis 7:48

Yeah, building relationships. That is the key part of this, my friend building relationships.

Pat McGowan 7:52

It's all about people, no question. And it's getting more and more about people every day, in spite of the fact that we've been, I think we've been kind of trained with social media and so on that we can, you know, live in our hobbit holes and still be connected, which is true. But actually sitting down and talking to people and getting to know them. And being with them is the only way to really connect. And I think we have an opportunity now, you know, to do that more and more on a global level, what possibly kind of put it all together and say we've got all these platforms now then. But when you go there, and just the relationship to the world is getting smaller and smaller and smaller. And it's not a virtual world. It's a virtual and a real world. Napa live in both. Yeah,

Dave Bullis 8:42

yeah. And you know, I'm guilty of that, too, where I tried to just, well, I did I consciously made that decision. You know, I don't know about you, Pat. But I got burned out from going to networking events. I mean, I got burned out. I used to be Mr. Networking Event too. And eventually I stopped because I said, You know what, eventually you start to realize, you know, half these people are never going to they don't, they're not going to make anything, because they really don't want to make anything they want to go somewhere and be seen and take photos and stuff like that. And your goals aren't the same thing as as them you know what I mean?

Pat McGowan 9:16

Yeah, I don't really know how to respond to that, Dave, because I do a fair bit of networking. And I usually end up meeting at least one or two people at you know, whatever the event is, where you ended up actually getting a good forged relationship button. You know, I think you're right. I think a lot of people are just going to party, a drinker, whatever their thing is, and, you know, you kind of have to be able to weed that out. We did a networking event networking event in Toronto about a month ago. And yeah, there were a lot of people there that were just for their for the beer. But a number of people I ended up developing, you know, some really good contacts with and relationships. With,

Alex Ferrari 10:01

we'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Pat McGowan 10:11

Because as we'll get into a little bit later, we're actually trying to grow a global movement. So that means that we, we have to find the people that are interested in having that connection, and then reaching out and having that global network. So that, you know, creators like us actually have a safer place to operate. So yeah, I know what you mean, though, like some of the networking events, there's a lot of posing and posturing and a lot of bullshit. But you do, you know, there's usually some pretty good people that most of these things.

Dave Bullis 10:44

Yeah, and I always feel free to always disagree with me. You know, most people do, it's always and it's always good to, to hear, hear two different opinions on the podcast, you know, and so let's just say, you know, go to these networking events, you know, whether they're in Canada like you are, or they're in the United States, like I am, wherever they might be listening to this, you know, what are some of the tips that you have for networking, you know, just like going out there and meeting people and, and some of the things that you maybe even like warning signs that you kind of see people to stay away from?

Pat McGowan 11:15

Well, I think the main thing is just to be open and honest and transparent. And, you know, again, you know, it comes down to some people skills to being able to walk up to somebody and say, Hey, my name is what's your name? What do you do? Tell me more, be able to ask those three or four questions that are going to get them comfortable so that they can, you know, actually participate in a conversation with you? Or if they're cagey, you know, you kind of break down their defenses a little bit. And, you know, so that you can actually have a one on one conversation, the thing I always watch for is eye contact, actually, if people are not going to engage you with eye contact, and it's going to be tougher work. Or if they're kind of, you know, looking around to see if there's a better person to talk to, and maybe they think you're not worth it, or you've gotten nothing for them. I also really kind of watch out for people that don't ask questions back, because that means that they're not engaged in the conversation. And if you got to prod and prod and prod, I'd say just cut it off, say thanks a lot and move on and go talk to somebody else. And you

Dave Bullis 12:24

know, I like that two packs, I think that works for, you know, even on, you know, virtual meetings, like, you know, if you meet somebody online, maybe see their Facebook or something or their Twitter or whatever, I you know, I found that people who just kind of, you have to keep prodding them, whether it be like, hey, this or that, you know, about this or that, or whatever, you know, they don't want to ask you about what you do, or whatever. Those are the generally that people were kind of like, alright, they're not in this meeting, and you know, what is wasting each other's time at this point?

Pat McGowan 12:53

Yeah, I would totally agree with that. But again, you know, like, we got kind of get back to this whole idea of what we do professionally to, and I interview a lot of people, I mean, I've actually, if I had to count the interviews, I've done, I've done 1000s In my career. And, you know, I kind of conduct myself as if I'm doing an interview, I like to ask a lot of questions. So if I'm trying to engage somebody, even on Facebook, you know, I'll ask them, What do you do? You know, What's your specialty? You know, what are you up to? What kind of projects are you're working on? What's pissing you off? You know, like, what barriers do you have in your, in your life right now that, you know, you could do better with? And I find that, you know, I'd say, I'd say that probably seven out of 10 people are willing to have the conversation, once they realize the big thing these days is no one wants to be sold to. And so they're always they're always on guard about, you know, what do you want from me, right? So, if you can kind of break through that, it's, it's easier to get a more meaningful discussion going. And yeah, hey, man, I'm not gonna lie, sometimes I am selling sometimes I do want you to get involved with what we're doing. But if you go right in with that pitch hard at the beginning, your chances are going to go down. So you know, you've got to really get get human, you know, have a human conversation, be sincere, be honest. And like I said, I think seven out of 10 people will generally engage. And the other three, well, you know what, so be it. No, no big deal, no problem, or maybe they'll come back later. Who knows?

Dave Bullis 14:36

So you mentioned doing 1000s and 1000s, of interviews, you know, so let's just go back to that and how you sort of got started doing that, you know, back to to actually going around and just, you know, talking to all these different people. So how did that whole journey start? Were you just going around interviewing all these people?

Pat McGowan 14:53

Well, I usually interview people when I'm on assignment. So if we're producing In your video where we need to collect interviews, or we're doing the doc, that's my job. So I'm the guy that sits in the chair and directs the shoot and does the interviewing. And, you know, I've learned a whole lot doing it. And I learned a lot about psychology a lot about people. But yeah, so it all starts with a project. And, you know, typically, I love to go in cold, I don't do a lot of research. When I do interviews, I want to explore the information along the path of the interview, rather than walking in with 39 questions and just running through the questions. We want to find out what people are passionate about. So you've got to read their body language, like interviewing is a really interesting thing, you're usually working at at least two levels, and us and probably three. So you've got your physical situation where you got to engage with body language that allows the person to feel a comfortable, but be also there while you want them to know that you're interested in body language has an awful lot to do with that, you can turn people off so easily with the Ron Ron body language, so you got to be really well versed in how that works. And you also have to be able to read body language to know know where you're going to go with this thing. The other level you're working at is at the intellectual level. So you're gonna, you know, I would say, you know, when I'm recording when I'm when I'm doing interviews, my brain is actually recording the interview so that I know where all the contextual points are, I know where the pickups and drop offs are, I know how to correct people, I know how to redirect them. So as I'm sitting there, you know, nodding and smiling and using body language, my brain is just furiously processing what they're saying. So you have to listen, and actually process it and embed it and store it. So that later in the interview, you can come back and make a make a what I call a contextual link to what was said before, and that is often when you get the best stuff. And then you've got the other of the other level, which is the conversation level, because now I've got to respond in a conversational way, it is actually reasonably intelligent. And, you know, unless people know that I'm, I care about what they're saying, I understand what they're saying. And I know enough about what they're saying to actually have them feel validated and engaged. So it's a really, really interesting process and you and you end up exhausted at the end of them, you know, some interviews, you just burned so much brain energy that, I mean, you need it, you need to go for lunch, like right away. So it's an amazing process, actually, and you know, a lot of people, you know, I see some young folks coming out. And the biggest caution that I would say is don't just run the questions, right? Don't just run the questions, get yourself into that conversation. Be interested in what people are saying. And you'd be amazed at what you're going to get. And one tip I always use with, with a lot of the people I interview is I don't respond to them as soon as they stop talking. Because sometimes if you leave a five second pregnant pause in the conversation, they're going to say what they really need, right? Because a lot of people get very nervous. And they're vetting what they're saying. And you know, we've had people in the chair crying because they couldn't do the interview. Because they were so nervous. But if you just let them sit, you know, just let it go. And don't stop the camera and don't cut. Sometimes that's when the best stuff happens.

Dave Bullis 18:47

I was giving you the pregnant pause there. But, you know, it's a friend of mine once gave me this piece of advice. And he said, he said to me that whenever he's negotiating, he always puts in that pregnant pause on purpose. Because he always says the first person that talks loses.

Pat McGowan 19:08

You know what, as on the business side? If you talk too much, you lose the deal. That's all there is to it. You got to learn how to sit.

Dave Bullis 19:18

Yeah. Alright. And then he's a fellow Canadian to bet. Oh, yeah. Where is he from? I believe he's from Toronto. Okay, because

Pat McGowan 19:27

that's where all the sharks live in, in Canada.

Dave Bullis 19:32

All he does is talk about the housing market there but that's a whole nother podcast

Pat McGowan 19:39

especially now. Yeah,

Dave Bullis 19:41

he all he does is talk about the housing market and he just liked it about the insanity of it. But But again, that's a whole other whole thing. Once you know maybe it's interesting, maybe something he's accusing some some people of like Chinese millionaires and billionaires.

Alex Ferrari 19:58

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show

Dave Bullis 20:07

of using these houses as sort of like a money laundering scam. I don't know if it's true or not, but you know, hey, you know, anything's possible.

Pat McGowan 20:17

While you're out there, and I think that happens in London, New York, Los Angeles, Seattle, Vancouver. Certainly west coast, definitely. There's a lot of Chinese money on the move. I don't know if it's dirty money or not. I have no opinion about that. But I know, you know, Vancouver, Vancouver is ridiculous. And it's actually more ridiculous than Toronto. But there's a big correction about to happen. So I wouldn't be buying any high priced real estate in Toronto just right now. I think I walk away from that.

Dave Bullis 20:49

Yeah, it's, I heard about that, too. But that correction, but But you know, just to get back to what we're talking about with interviewing. You know, I wanted to ask you a question. And I'll and I'll, you know, I'll tell you my funny story. First, I want to ask you about one of the worst interviews you've ever done. Because, again, we always learn more from our mistakes than from our successes. And so what happened was, when I was working in higher ed, they had asked me, so I do this, some, this probably is the worst one, but it's the funniest one. So they asked me to do this, this interview segment with the girls volleyball team. And the coach who, you know, who was a part time coach showed up late. And he has all these questions, just hand skills scribbled on a piece of paper, it's all you know, cut up, he just ripped it out of a notebook. And he's asking these questions, all these girls are talking about stuff that I could never ever use. In a school setting. They're talking about doing drugs, they're talking about their, their, their trash talking their teammates. They're doing this and that. And the coach was reading the same questions to each girl because we told him to. And then he would be, you know, ask a couple of different questions here and there. And finally, when he asked me, he could have I put the cut up, put this together. And I said, you don't want me to use any of that. I said, you know, except for one girl, you ever lose girls where you do trash talking girls, shit talk and this and that. And he goes, Yeah, I guess well, you just put something together. So I put this thing together. And bat let me tell you his face dropped. And he goes, I he goes, You're right. I could never use any of this. He goes, it will. It was it was the was so hilarious. Because what I would do is I kind of given that the MTV self editing, where I was like, here you go, here's what they think of this, this and this. And it was like, you know, they they thought, Oh, what do you think of this thing? Oh, it's terrible. It sucks. Bah, bah, I'm like, you can't use any of that you can have in school promote this. But it was just it was just hilarious. Just because of how ridiculous it was so bad. I want to throw the question to you, you know, what was one of the worst, you know, times you've had, you know, doing an interview segment?

Pat McGowan 22:53

Well, I was telling you a few minutes ago, I had this this poor woman who was so upset that she couldn't perform. So you know, this is one of the things that we tell people do not try to memorize what you're going to say in the interview, like, don't take our quietly a lot of a lot of the institutional or government types or you know, bureaucratic types. They want you to send them the questions in advance so they can prepare. So they ended up writing, you know, writing banner, so that they can answer these questions. And it's just ridiculous. They come in with no, like pages and pages and pages. And it just like, I'm gone, you can't possibly like, there's no way you're gonna be able to do that. And this lady that I was working with, and it was a very serious subject matter. And she was like, the CEO, and she was brilliant, really intelligent person, very, you know, beautiful woman. Clearly very professional. But boy, she was nervous. And I could tell as soon as she walked in the room, it was going to be trouble. So we got her in the chair was in a studio setting, you know, everything's controlled environment. And we got her in the chair, and she could not just could not do it. could not do it. And I think she had like a tiny little nervous breakdown. Anyways, we had her in the chair for two hours, because she wouldn't quit either. He kept telling her, you know, you need to take a break. You know, don't worry about it. And we're being really, really kind, you know, and accommodating. And she was in this chair for two hours, and I thought she was just gonna snap. It was it was a horrible experience. It was it was painful, actually, for everybody in the room. Even the camera guy and producer was in. But her colleagues were in the room and everybody just felt so bad. So that's, you know, I know that's not like talking to a bunch of teenage girls trash talk and each other really have that experience. But, you know, that was probably the worst one and it's just terrible when you get people who are so upset. that, that they're judging themselves so harshly when all they have to do is just talk like we're having coffee, right. And I've got like a zillion techniques that I use to get people to settle down and to relax and stop being so freaked out. But sometimes they just don't work, you know, they just don't work. And, you know, some of the worst ones we do are actually when the client, you know, tells us, well, we don't have travel budget to send you the location. So, you know, we're gonna hire a camera guy locally, and can you direct by Skype. And those are really, really hard to do. Because you don't have the personal connection, you can't do eye contact properly. And if you get somebody who's tough to deal with in that situation, you know, sometimes the clients grinding on you because Oh, I couldn't you get I worked so hard about this, and I'm going well, you know, I guess you haven't done several 1000 interviews, so it's gonna be hard for me to explain this to you. But they sucked. So what do you want me to do? I can't force these people that to give a good interview, basically. So yeah, I mean, there's a lot of pressure and, you know, there's money on the line and everything. So my attitude is always the same. And I always asked myself this question in all production situations, it's basically like, who's gonna die here? Like, what are the stakes? Okay, so nobody's gonna die. Everybody relax. Let's just, let's just do our jobs. And we're do our good jobs. We're all professionals just get this done. But, you know, we don't need stress and pressure in production situations. It's just, it's just a completely ridiculous waste of time when you do that. Yes,

Dave Bullis 26:46

I could not agree more, man, I have been a part of both of both productions like that, where it's been, you know, sort of more loose, and then other was where it was just, you know, you walk on set, and you could just feel the tension, you know, with it with the director doesn't like the DP, the DP doesn't like the producer, or the producers and the director. And you're just kind of like, wow, you know, who the hell needs this stuff?

Pat McGowan 27:09

It's just bullshit. Yeah. So, you know, I came to a point in my career where I just said, I'm not doing bullshit anymore. I'm not, I'm just not doing it. It's not worth it. So now, I haunt situations with my startup blackbox, where it's a no bullshit deal. And even when I do some freelance work, or doing contract work, I just, I try to work at so that there's there's no bullshit, and it's all about the work, and doing good work. And, you know, making sure they have a pleasant experience, and you end up with a good product. And that's the bottom line, because there's just no need for that.

Dave Bullis 27:49

Yeah, you know, that's so true. And I also liked that phrase, you know, there's no more bullshit products, or projects, I'm sorry. And there was a point, by the way, Pat, where you know, what, what was it? Was there a project in particular that finally just set you over the edge?

Pat McGowan 28:06

Well, you know, that's a big question gates. So let, the answer is yes. And no, I had a huge project that we had one that was a museum job. And it was a million dollar contract, it was a big, big contract. And there were a number of players involved, design agency out of the states, and a lot of curators and a lot of experts. And it was a very, very difficult project, the product at the end was absolutely wonderful. But there were so many human imposed turf defending types of interactions during the process, that it really became a very unpleasant project. And it could have been, you know, really rewarding to do. So it was just basically people being people, you know, and defending their turf, and, you know, whatever was going on. And really, it was during that project that I said to myself, Okay, I've been in this business a long time, I've had a great career. I think I'm ready to move away from doing this type of work. Because the bureaucracy and the layers of crap, were sucked the soul right out of your chest, and then you couldn't even be creative anymore. Because they took all the fun out of it. And, you know, I don't want to be cynical or anything, but there's a lot of that going on these days, right? Where it's just, there's so much bureaucracy, there's so much political correctness. There's so much business pressure that honestly a lot of these jobs just aren't fun to do anymore.

Alex Ferrari 29:53

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Dave Bullis 30:03

Yes. And that's what happened to me too. When I got burned out, not even just doing freelance work. But like other work in general, you know, and just, you know, here's another story for you. I when I was doing freelance work, somebody asked me to come do this very. So they said, it's just an interview, they said, it's just an interview, we're going over all this stuff, etc, etc. And I get there. And it's a completely it's a whole 180 from what they told me it was going to be. Instead it's, it's a competition. It was just a competition about who could use like, who could, you know, use the soul the fastest or whatever. And it was like this whole sort of convention. And I said to the guy said, Wait a minute, this is completely different than what you said it was gonna be. And I mean, he was like, Well, for me, it was the kicker was too bad. I showed up there. And he had no idea who I was. And I said, Aren't you and I won't use his name. And I said, Aren't you blank? And he goes, Yeah. And I said, Well, I'm Dave, I, the videographer. He was Viagra for what? And I said, Well, you're doing some interview thing today or something. And he goes, I don't know what you're talking about. So I go outside. I looked at the business. And I'm like, wait, yeah, this is it. This is the place. And I call my friend who had who had introduced us and she comes out, she goes, Oh, yeah, that's him. And I go back in there. And I look at him and I say, hey, you know, Dave, we've been talking back and forth, like a month now. And he goes, Oh, yeah, I forgot you were coming. And I'm like, Jesus Christ. This, and it just went downhill from there, Pat?

Pat McGowan 31:29

Well, you know what, you know, I don't want to get on my on a negative soapbox or anything, because, you know, things have changed, that's for sure. But this is just an example of how I think. I think the perceptions of what we do in the industry have changed a lot over the past five years, let's say. So I think the perception of, you know, how professional we are, how well trained and experienced we are. I think some people think that we are a bit of a commodity, right? You know, it's just a video guy. Oh, yeah, whatever, right. But they still want it done perfectly. But I don't even know what that entails. So, you know, like I said, I don't want to get down on it too much, because I'm gonna sound like a grumpy old man. But, you know, things have changed. And the perception of what a professional does in our industry and who they are, has has changed a lot. And, you know, quite frankly, I think, in a lot of instances, we're seeing a lot of bad work being done, you know, in that context, and the clients don't even know that it's bad work anymore, because the wrong person on their team is actually handling it. So, you know, we got this weird thing going on right now where, you know, it's, and it's always been that way. I mean, we always had what we call the bottom feeders in the industry that just did shitty work. But everyone knows who they were, and so on. And they, you know, they got hired on certain gigs, but usually not. And those of us that were kind of working the higher end of the market, and we knew we knew who was who. But these days, it's like, you know, if I didn't tell a client, I have a client, tell me one more time to me eating well, you know, you guys are just super overpriced. Because, you know, actually, my son is taking film studies, and he's gonna do it for us for 100 bucks. And, you know, I just got tired of having those meetings, honestly. And these days, you know, the question, the one question I get asked by my clients in meetings is, can you do it cheaper? consistently? So, it's time to say, actually, no, I can't do it cheaper. And if you want it done cheaper, you can get it done by somebody else, no problem. But you know, at the same time, the work is a little more scarce than it was, let's say 10 years ago. And the prices of the higher price jobs are actually coming down. So we're looking at a situation where our market is becoming commoditized. As, as I say, you know, we are less of a custom valued service than we were we're now expected to do work. For the same rate that we're working for, Hey, man, 20 years ago, think about it. The rates haven't changed really very much if at all, and now they're going down again, for the contract work that we do and video and film.

Dave Bullis 34:45

So, so what point you know it again, when I read your bio, you mentioned that, you know, you realize you woke up one day and you realize you have been disrupted you know, and I think that's a big part of it. Because what you said there is with with you know, hey, I'm just going to have my Don't do it. I actually, let me tell you I've had other people say that too. And, you know, you're I'm gonna have my son edit this or whatever else. And, you know, it's a game where poverty if you think that, you know, your son could do it, you know, it's just one of those things. But so at what point did you then create, you know, black box?

Pat McGowan 35:21

Well, it's I created black box where I didn't create it three years ago ideated it three years ago. So I, I was sitting in my boardroom, realizing that I had built, you know, a beautiful company, I had 40 employees, I had offices in two cities, had a really great team. And I realized that the market had changed. So I realized a couple of things. First of all, we were involved in some broadcast work here in Canada. And I mean, you're familiar with the cutting the cord phenomenon, but what happens in markets like Canada is when the cord gets cut, the cable fees that people were paying are no longer allocated for broadcast production by the broadcaster's because that's how they get their money. And, and then in our market, the Canadian government has, you know, some fun matching programs and, and so on tax credits, that are all predicated on the broadcaster's coming to the table. Well, the broadcaster's stopped coming to the table, because they were making less money because people were cutting the cord. Now, why were they cutting the cord to go and watch content from digital platforms like Netflix, and YouTube and what have you. So that's the first thing that happened. The second thing that happened at the same time is that technology became much more readily available with the advent of DSLR camera technology. So all of a sudden, the cost of acquiring equipment went down. If that's what you were gonna buy, you know, it wasn't high end gear, it was low end gear, but it was low end gear that was doing good looking product. And the third thing that happened is, we have a lot of young people coming into the market, and people like to beat up on millennials. Personally, I don't think that's right. I know a lot of millennials, and I really liked these guys. But unfortunately, they came into a market where they could tool themselves. And were competent enough because they were doing some good work. I mean, when I say that the son could do it, the son could really do it. But the son should have been getting paid 500 bucks a day rather than 100. That's my point. So the commodification happened on the perceived value of the of the work right, from the client saying, Well, my kid can do it for 100 bucks, rather than you doing it for 500 bucks, or whatever. And we're 1000, you know, which is what we used to get. So now we've got these three factors, we've got a glut of labor willing to work at lower pricing, and why would Millennials work at lower pricing? Well, a lot of them were either living in apartments with roommates, so they don't have car payments, they don't have college funds to build, they're not building for retirement. Now they're young. And because he used to be, you know, there were barriers to entry coming into the market. If you were going to be a video production company owner, you better have the ability to acquire capital. So you could buy high end cameras for $100,000 each. And IT systems cost a fortune, you had to have an edit bay, you had a voiceover booth, you had to have a small studio, but all that's gone now like people kids are at these millennials. Sorry, again, I don't like the term but younger people. You know, they're editing at Starbucks, or they're forming into collectives where they're sharing small office spaces, and that's okay with them. Because they can cut the video on on a on a MacBook, or a surface or whatever. And they can shoot it on a DSLR. And they're not using a $20,000 Sachtler tripod anymore. They're using $1,000, you know, vinten or whatever, or a man for auto. So everything. It wasn't just the one thing commodified and disrupted, everything changed at the same time. And then you had a lot of institutional clients like government clients or, you know, businesses, even bigger businesses, smaller businesses, bringing somebody in house, so they would hire a young person to do it in house. And why well, because the young person had the camera had the edit bay, in their pocket, had control over and these kids are quite well trained. And they're multifaceted. Like they can shoot and edit. They know how to do audio. They're not terrible, and they're good at it. So you know, this disruption had to do with that whole change from you know, a team of three or four people doing work.

Alex Ferrari 39:54

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show

Pat McGowan 40:03

to a team of one or two doing work that didn't have an office probably weren't insured. You know what I mean? Didn't have staff. So all of this happened at the same time. So here I am sitting there a 25 year veteran of the business. And yeah, we did get disrupted, we got disrupted at three levels. We have in 19, or 2015, we had four, I believe, for broadcast projects cancelled. Because at whatever, there were three different broadcasters involved, we're laying people off. So you know, there were just canceling series, and we had four series canceled was a huge amount of money involved. So yeah, we got hit pretty hard. So I'm sitting in my boardroom with my wife. And I'm, I'm like, Okay, we're not making money, who's making money? What's going on here? So we sat, and we did a bunch of research. And we concluded that there were two ends of the spectrum that were making money, there was the YouTube crowd. And that was prior to the YouTube pocalypse that happened a year or so ago. And that was before they changed the monetization. But that's another problem that we can talk about. But there were a lot of YouTubers were making money. And we found, you know, we just said, let's go look at the top 10 YouTubers and see who's making money and see what they're making. And you know, as a kind of a trained, experienced filmmaker, it was pretty shocking, because I hadn't paid much attention to YouTube's Stupid me. And you're kind of looking at going, wow, this stuff is popular. Why? Well, you know, we kind of figured with a couple of things. It was probably because a four year old sitting in the back of mommy's SUV, hitting the iPad again and again and again. And people were making millions of dollars. There's this one channel we found called Disney collector. And this is a Hispanic woman with really nice, Blinky fingernails, and a really sweet sounding boys, who shows you how to use Play Doh. Right? Disney character playdough shit. And the woman has has now got 250 million views on one of her videos, or more. And she's were purported to make $12 million a year or more from her YouTube box. Okay, so that's just a wild an eye opener. And then I looked at the other end of the spectrum with Netflix and Netflix had not even started to I mean, I don't even think Orange is the New Black had been produced 2015 Yeah, maybe it was that I guess they're going into season four, at any rates, and we started to think, Okay, well, we've got this distribution platform that's actually starting to create content. So what they're doing is they're aggregating the rights to intellectual property at the top of their organization. And producers who used to make shows own shows, and license shows to broadcasters, are not going to be able to do that for very long. So maybe you kind of think, you know, the term that I believe came to me at the time was user generated content. So you've got YouTubers making user generated content, and you got Netflix making user generated content. But we're creators and all of that. Well, in the YouTube case, you've got one or two people making the stuff there are very many teams of trained people doing it, although there's lots of cool stuff going on in YouTube right now. But in the in the Netflix example, basically, creators were turned into workers. So and that's not bad, when the rates are good and everything, but as I understand it, you know, the rates are dropping. And the people that I know, in markets where, you know, big platforms are making a lot of content. The rates are static, and they're still installed. And even studio owners and equipment rental houses are getting really, really pushed down rate. So basically, you know, everybody's making money except Netflix. And people who want a gig in this industry, you know, they're really just looking for work. And they're being forced to take longer hour days for less money. And I'm not saying that's happening everywhere. Lots of people are gonna say, Hey, man, that's not true where I am or whatever, but it is true where a lot of people are, because through our platform, I hear these people, I know them, and they want a better deal. So I decided to create a platform that was all about creators, being able to do user generated content alone or in groups, and gain access to global markets not have to sell themselves as workers, but convert to being own Because of the content that they make, and take advantage of all the licensing fees, longtail revenue, or residuals, they're all the terms apply and do better in their lives. And we want to do that on a global context, where every creator all over the world actually has the same access, because they have the same access to technology and tools, but they don't have the same access to markets and business systems. So what we designed as a platform that is really has really captured and automated all of the things that creators need, in order to work together to make content to co own the content, and to share and the revenue streams have to develop through these new digital platforms. So we think it's really revolutionary.

Dave Bullis 45:48

So it's, you know, you touched on YouTube. And, you know, I had friends who were creators who saw their, their, you know, their monetization, cut down some channels, hell were even gotten into trouble with all the new rules. You know, I have another friend who's just getting back into it, and he has one of the top YouTube channels ever, which is crazy. But, but just going back to black box, you know, it's, you know, it's allowing. So basically, it's a, it's cutting out the middleman, essentially, you know what I mean? It's, you can actually, you know, go on there and actually don't have to worry about, you know, selling. You don't want to say you basically cutting out the middleman. Yeah,

Pat McGowan 46:31

oh, but I think I can help you understand a little bit, but we're not cutting anybody out. Because they're already cut out. Okay, being a producer is a much harder game, because you be actually been turned into a worker again. Now, there are people who are, who are developing product as producers and selling it to Netflix or licensing Netflix, and that hasn't died. But a lot of that business has gone away. So what's happened is, like people that used to be producers, like actual producers have become service producers. So they're getting paid, you know, by whoever their client is. And that could be ABC, NBC, it could be Hulu, it could be Netflix could be anybody. They're getting paid to manufacture the project for those companies, not with them. Right. So that's really changed. So everybody all the way down the line is now a worker. But and that would be fine. As long as as, as the, you know, the disruption wasn't happening, where the rates were dropping. So I mean, it's bad enough that that the business model changed to the point where people, you know, couldn't own their own content, but, but the rates are going down. So what does that mean, for the future? Well, you know, means we're gonna have a commodified labor market. Look at what happened in visual effects, right? Visual effects, you used to go to LA, and you go down by Santa Monica Pier. And there were all these nice two, three storey buildings that were full of visual effects, fences. Well, they're all gone now. And there's a saying, in Hollywood, amongst certain executive producers, that said, that goes like this. And if you haven't put a VFX company's company out of business on your film, you're not doing your job, right. So what's happened with VFX? Companies? I mean, when you go and see blockbuster movies now used to see like ILM wouldn't be in there or whoever, right? Well, now, you see, look at the end credits, there are hundreds and hundreds of people who employ it in the VFX game, but they're working for 50 companies. Right. So instead of seeing ILM crew of 200 people on the end credit that you now you're seeing, you know, 50 companies with 10 to 15 people. So what's happened there is that the VFX companies have been divided and conquered into smaller and smaller units. So now the producers, the big guys can actually go in and hammer them on price a little more effectively, because they're playing them off against each other. And I know that sounds horribly cynical, them you know, if there's a Netflix exact listening, you know, hey, I'm just coming from the Creator perspective, right? Where I think that there's a better deal for creators, the creators should, and can now have the ability to have their piece of the pie. And to have better lives as a result of that and to be able to do the work they do with a lot more freedom. You know, I create a black box to have more freedom for me, and for my Creator colleagues, because we are special people, you know, I call it the Creator class, actually. And so the Creator class for me are people who are talented, generous, kind, hardworking, resourceful, honest, people.

Alex Ferrari 49:56

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Pat McGowan 50:05

And I would say 99% of the people that I know there are creators fall into those categories. So that means we're gonna get beat up as business people, plain and simple. So what we do is kind of give a we create a platform, that's a safe haven, that allows creators to actually not worry about all that business stuff. Because just like so many other businesses, we want to automate a lot of it. So that there's not a lot of backroom deals going on there, the sharks can't play, you know, basically, we put a product and we move it through a market just like any other industry, you look at the auto manufacturing industry, right, they've got this thing called the supply chain. And the supply chain means that all these parts are created by all these suppliers, and brought together at the assembly plant. And it has to be it has to be all coordinated properly. Well, you know, on making the movies, no different than building a car, it's a supply chain, you have to bring all these resources together, they have to happen at the right time. budgets have to be respected and and then you deliver to the customer. So what I've done is created a platform that allows creators to be part of the supply chain, and to own the end product as they're moving along. So it's a really, it's a really big shift in in terms of an economic reality. We liken it, Dave to a return to the guild system, you know, prior to the Industrial Revolution, where guilds actually had these inherent protections in place. You know, if you were building a cathedral and you need his stonework done, you went to the stonemasons and the Peter needed a bunch of pews pews down and woodwork done in the church, you went to the carpenters guilt. And so what we are is a Creators Guild, and we're global, and we're digital, and we are going to change the face of the industry.

Dave Bullis 52:06

And I know exactly where you're coming from, by the way about the VX subnet, the VX situation, I actually have a friend, what are you cuz I've had, I've actually had friends who've worked in the industry, and they were describing, you know, pretty much what you just described as well. But you know, black box looks awesome. I'm all in favor of anything that allows, you know, creator, creators, good creators, to, you know, to share their stuff and to actually get seen, because, you know, like I've said before this podcast, the idea of just uploading something to YouTube now and saying, Hey, it'll go viral is like a one in a million shot. And you can't rest anything on that, that's on a

Pat McGowan 52:43

business plan. For sure, man. Well, that, you know, that's just that standard fragmentation. But we're working within a global context. And we're working within a digital platform context, nobody's done this before. So no one really knows the rules. But we do know that there is an awful lot of money being aggregated at the top of these multinational corporations. And, and then you then you have to bring in the idea that they are some of them are publicly traded corporations. So that whole dynamic is very different to so who end up who ends up getting caught in the vise, are the individual creators, because in fact, as these companies blew apart, you know, big either company with 40 people, right? And that company is pretty much gone now. So the protections that were afforded to the workers within that relationship, they with me as their boss, there are oh now, right. So what we're doing is we actually say, Look, we don't want to aggregate these people back into a company again, but we want to have a platform that performs those functions for them that allows them to have a little more predictability and security in their life. So I should tell you that we analyze the market and we said, look, ultimately, we want black boxers, we call them black boxers to be able to do the work they love to do. So if they are, they want to work on feature films, and they're a gaffer, we want them and they love being a gaffer, we want them to be able to be a gaffer on a great feature film, on regular work. And if they're an actress, we want them to be an actress. And if they're a musician, we want them to be a composer, we want them to be able to do what they love to do. So what we allow them to do is come together into groups of like minded creators and make the project they want to make that is that has a lot more creative freedom for everybody. Now, not a lot of not most, sorry, not most, a lot of people, they just want a gig and they want to get paid, they want to go home and they want to be saved and they want to make money and they want to take care of their families. And that's that's never going to end but we offer an alternative to people who you know, kind of feel that desire to to really be involved in something That takes a lot of craft a lot of love, and ends up being a very valuable product. So I'm going to give you an example. Moonlight won the Academy Award two years ago. And Moonlight was made for reputedly 150 Sorry, 1.5 million bucks. And then there was a big marketing budget, well, not big 5 million, probably the one against it. So moonlight ends getting ends up getting a theatrical run that did well. And then they ended up doing very well on VOD, and cable, and they won an Academy Award. And, but I have to wonder, okay, this movie is going to make $150 million after production net? Who's getting that money? Is it the people that sacrificed their rate showed up? Did the extra hours put the love into it? And made the movie? Or is it somebody else? Well, I think we all know the answer. Is it somebody else? So what if my question is, what if a group of filmmakers could come together, make a product like moonlight. And now the budget is not going to be 1.5 million because no one's getting paid, you're doing it in kind for ownership in the movie. And then if you've got some fixed costs, but we can bring everybody into this scenario, studio owners that are getting squeezed, can actually let us use the studio for a piece of the movie camera department. Maybe they've got two year old cameras that aren't being rented for full price anymore, that they'll put on the movie for a piece in the action. Craft, anybody, anybody involved location owners. Transport, that works. And you're still gonna have some fixed costs. So now you can make the movie for a really good movie for two or $300,000 or less. It all depends on you know what your consumables are. So now you make the movie great. And it's owned by the people that made it. Okay, this is a key thing. Now, if that movie goes out, and it makes $150 million net after distribution, or whatever, okay? And you can even bring a marketing team in to be part of your group. So you don't have to go pay for marketing, you can find a marketing group and say, Do you want to be part of this, right? Anybody can be part of it, the district distribution, people can be part of it. So you create this wonderful waterfall saying, okay, all these dollars that come in, they're all going pro rata to the people that own the property. And by my math, on a $1.5 million feature that does $150 million net after distribution over a period of time, because it's long tail money. And that's how money gets made on distribution platforms now, everyone would get paid 100 times the rate. Good, bad. What do you think? That

Dave Bullis 57:52

sounds like a good, a good trade off.

Pat McGowan 57:54

Yeah, man. So where we started is saying we're gonna dream big, right at BlackFox. We're gonna dream big. We're gonna say, we want to make blockbuster feature films, we would love to be able to make a Black Panther in five years, and have all the people that made the movie, get a really nice paycheck, right? Because they deserve it. We love these people they need they need this opportunity. Because right now, it's just it's not working out. So good. Right. So that's our dream. But we couldn't start there. So we decided to build our platform in a smaller, more highly defined market. And that's the stock market. So currently, our platform service is stock footage. So what you can do is you can take your camera right now, like you're a camera guy, right? Yeah. Okay, do you own your own gear?

Dave Bullis 58:48

Yeah, I have over here. Actually, it's actually right behind me. You can't see because it's a podcast. But yeah, sorry about that.

Pat McGowan 58:53

So what kind of camera Iran,

Dave Bullis 58:55

I have a Canon Rebel. I think it's the was it the 6070. Okay,

Pat McGowan 59:01

so let's say you've got a 60 You could probably walk out of where you are right now. And it's not daylight there anymore. So let's say you get up in the morning and go for a while. And you see something beautiful that you want to capture. So you do it. And then you see something else you want to capture, or maybe, you know, whatever. And this is a very simple example, might you so but you can then go home. And you can actually curate that into five very nice clips, that you can put them up to our platform, we'll take them out to all the big stock agencies. And when the money comes, it returns to black box. And then we take 15% of the net sale and we deliver the rest to you. So basically, it's an upload once get too many scheme. Now, let's say you go back to your house and you say, Oh, I don't really don't want to edit this. Pat.

Alex Ferrari 59:58

We'll be right back. After a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Pat McGowan 1:00:08

You want to edit this and you call me up and say you want to edit my clips. I'm like, Yeah, sure, I'll do it for 30%. And you go, Okay, deal 30%. So now you can upload those clips to black box, your, or send me sorry, send me the raw. And I will actually edit them, upload them, tag them and do the metadata. And then when, and then when the money comes blackbox auditing automatically pays me my share, and you automatically get paid your share, you don't touch my money, don't touch your money. Or another option is you want to edit but you hate doing the metadata, you hate doing the keywords and the descriptions and all that. So you can actually edit them, upload them and then hand off to me. And I'll do the metadata. And I'll do it for 15%. So that's what we built, and it actually works. So we've got 1000s of people all over the world doing this. I just saw a project go through where a guy in South Africa had 700 clips, he put them all up on the platform. And he assigned the curation to the metadata curation to, to a woman here in Ottawa, where I live actually has a very good out of there. So now we've got this nasty international collaboration going. And it all happens within our platform. So that's where we started. And our next move is into short form and long form. And you can do YouTube videos this way. So like, like I said earlier, a lot of YouTubers, they want to do everything themselves, because they want to keep the money, right? Like, and they don't know what they're gonna make. And it's like, it's all freaking everybody out. Well, what have you said, Well, why don't we do this as a team? Why don't we actually do some produced content, where we actually use real writer, real director real, you know, real, real real. And everybody works together and make some product as watchable. And then you put it the black box, and we manage the whole process of getting it the audience, and then dividing the revenue. And it works. I mean, that's all I have to say it works. It works really, really well. And then as as, as we grow, we're going to take on bigger projects, indie films. Right now, if there are indie filmmakers that have had no luck distributing their film, you can contact me and I will find a way to get your film onto our platform, you will have to go back and figure out who did what on the movie. So you can make sure that everybody gets compensated when the money comes. And then we will, through our developing relationships with distribution, and VOD will have a good chance of getting your movie seen. So this is what we're trying to do.

Dave Bullis 1:02:49

And, you know, I think that's great. Too bad. I mean, you mentioned you mentioned Black Panther. I'm always in favor of movies like like moonlight, where or movies like, obviously, the Blair Witch or paranormal activity, you know, those movies that come out of left field that just, you know, a go, they go apeshit, you know, Big Fat Greek Wedding, you know, these movies that are shot for, like $20,000. And they have a pretty good return, you know, and, you know, just just as we talked about, you know, gear and producers and stuff. You know, I once had a friend of mine who was going to make a movie for 10 grand, and this, this person who owned a rental house, got a hold of them. And he came back to tell me, he goes, Dave, I can't do over 10,000 anymore, I need a quarter of a million. And I said, Well, I said, No, you don't. I said with a fool of God, you don't need a quote, I've read a script. And he did not need a quarter million dollars. He could have done it for $10,000 at the max. Because it only took place in one room. There was no stones or explosives. There's no squibs there's nothing there's no famous people that were needed, or were going to be in it. So I was like, man, just just don't even worry about that stuff.

Pat McGowan 1:03:59

Well, you know, the whole point here is that making a good like, you can make a movie, anybody can make a movie, I got an iPhone, I can make a movie right now, like no problem, right? But are you going to make a movie that's going to be compelling that that someone's going to want to watch. And yeah, you can bank on having the next Blair Witch or whatever. But I believe that for the same reasons that our labor market have disrupted, we have an army of young filmmakers who are actually quite talented and capable, who are coming along. But the problem is they're trying to do it all themselves. Like they're trying to self self produce, self make and self distribute movies. And I think that that's a missed opportunity. Because when we put together when we put groups of talented people together, it makes for a better product. And we work together and we try to develop platforms like black box that help people do the business end, which is often where things fall apart, right? Like for example, you know, I make a movie For 10 grand, and I call in all the favors in town, right? Well, if that movie ends up going viral and I make, I don't know, two and a half million dollars on it, how much that money is going to go back to the people that helped me. There are no deals in place. There's no structure, there's no system. And it's very likely that those people aren't going to get paid because they did it as a favor. Right? So what slack bots does is eliminates the favors. We don't do favors. And we don't do deferrals. No one ever gets paid on deferral, you know, anyone that's ever paid on deferral? It's a big joke. I know. I know, Hollywood actors, you know, who I talked to, like, I was talking to a guy named Martin Cove. There was the sensei and the Karate Kid. And Martin's a great guy. And I said, Hey, Martin, how many deferrals Have you ever been paid on, he just laughed. He laughed. He said, No, and people don't get paid on deferrals. And he's bullish on black box, actually, like, there's a lot of actors in Hollywood that will that'll do this, because it's not a deferral. And it's not a favor. And it's not a rate reduction, either. It's a fair share of the movie that you make. So if it makes money, and when it makes money, you get paid your share, our system is guaranteed to pay you. So suppose for a guy that wants to do a $10,000 movie, I would say, make a million dollar movie, but make sure it's all in kind, and then your fixed costs will only be $10,000. If you happen to have to buy some squats. So bring the rental house in as a partner, bring the studio in, as a partner, bring the locations in as a partner, bring the actors in, bring the crew in, bring everybody in as a partner. I mean, even in the point where you're making in India, and you say you know what, we're not catering this, bring your own lunch, right? And, and make a great movie and capture the passion of all those people and get the best people involved. Right, like don't get your cousin to hold the boom, get a sound guy to do it, get somebody who's really good at it to do it. And then guess what you're gonna have usable audio and post. Right, and you move you're not gonna sound like crap. And you can get yourself a decent composure. And, you know, it just goes on and on and on and on and on. And we learned all of this through the stock footage thing, because you know, what we see, we see people who are learning faster, doing better work and making more money. We've got people actually on our platform right now who are getting ready to quit their jobs, and they're not taking gigs anymore, because they're making enough money off of their stock footage portfolio, to to float their boat. And now what they're doing is they're saying, Great, I'm floating my boat from my stock work. So I'm going to go make my movie now. And they're going to make it using a black box, or the black box platform. I know it's a big idea. Like a lot of people are sitting out there in your audience right now going What the hell is Pat talking about? I don't get this at all right. But because it is a huge, huge shift. It's an absolutely it's, it's a paradigm shift. Like it's revolutionary. And I'm not saying that because you know, hey, you know, Pat's, a smart guy did a revolutionary thing. I actually did this, so that I could have a better life facing a disruptive market. And I did it so that my peeps, the creators who I know, could have a better life too. And we did it as well. So that the guy living in Nairobi, which is a bad place to be right now with all the flooding, but the guy living in Nairobi, could go out and capture images of all the wonderful natural beauty that there is in Nairobi, Kenya, as opposed to having a bunch of white guys flying on a plane with an airy Alexa and, and meanwhile, imagery and all the guy God was in his Puerto feet. So we can actually go in and entertain that guy, and maybe even help him get equipped, so that he can be the content creator, because he's possibly very talented. So we're gonna liberate a lot of creators using this platform, and we're gonna flatten out the world, and we're gonna make it a fair deal.

Dave Bullis 1:09:15

Yeah, and when you were talking about everyone getting paid deferrals and stuff like that, it always reminds me of the what they call the Hollywood accounting side of things, where, you know, you know, we will get points and in the movie never turns a profit, so you never see those points. But when you were talking about blackbox, Pat, I, you know, all of this, you know, makes sense to me. It sounds like a really, really, really cool platform, where people can actually collectively get together. And if you do decide to hire this DP or hire this person or hire this, whatever, you know, people will get, you know, people who now are bound to get paid rather than deferrals or like, you know, promises or, you know, whatever.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:56

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Dave Bullis 1:10:05

Which I, which sometimes by the way, you know, I just want to mention, I've seen that getting people to a lot of trouble before to deferrals. You know, I actually had a project that, that I saw I was involved in, and feelings were laid out on Facebook. And you know how what happens, that pattern just snowballs, and all of a sudden you have people yelling at each other and social media?

Pat McGowan 1:10:29

Exactly, it just gets ugly. Exactly. You know? Well, you know, the one, the one point I would like to leave people people with is that you can work or you can earn. Okay, so blackbox allows people to earn, it converts you from being a worker into an earner, and an owner of the content that you make. It's like, it's like, you know, there's lots of good analogies out there. I think farming is a good analogy. Do you want to be a paid farm worker getting a low rate? Or do you want to be a sharecropper, and own part of the product that goes up? You know, and so what we're creating is an environment where you have that choice, because nobody works. In black box, there, it's not a job, it's not a gig. Not at all, actually, it's very different. And just so everybody knows, the website is www dot black box dot global, it's not a.com, it's a dot global. So www dot black box dot global, I had to throw that in there, Dave. And, you know, come to the website, check it out, see what you think. It doesn't cost anything to join this. If you do join, you know, we want to see you get active, and we're gonna try to help you do that. But it's not free candy, like you got to work, you got to do the work. And, you know, there's stuff that you have to do, you got to make content, you got to edit it, you got to curate it, you got to upload it. But if you're trying to go to five stock footage libraries, right, now, you got to upload five times. And it is not fun work. So we take that whole aggro out for you. And then if you're trying to share revenue with a collaborator, you know, like, for instance, if you want to do a shoot tomorrow with three models in a cafe, you could actually instead of having to pay the cafe and the models, you could say to the model in the cafe and find people who are willing to do this, to take a share of the revenue or the footage. Awesome. And we got a lot of people doing this, we have a member that did a cool shoot in a hospital and did a whole bunch of medical stuff. And everybody is getting paid on a share basis. So you see these little micro transactions going through. But it adds up. There really does like a lot of the stuff that I've done, I've been lucky, you know, I'm not a genius cinematographer or anything, but I know what I'm doing. And I've done lots and lots of shoots, where I go out for a week and do wildlife stuff, where I would have gotten paid anywhere from six to $10,000 For the week, if I was working for network. And my projection on some of those shoots is $100,000. To me, because the market is so the market demand is so high for that type of footage. So like you can make your day rate over a period of years using black box, or you can make five to 10 times your day right or more. And we've got lots of examples of that are some really spectacular examples of people making a lot more money doing this than they would get on a game. So it's looking really, really promising. We're really excited. And we really want to welcome as many creators in I mean, Dave, I'm going to invite you to join but just go to the website and register and maybe you got a bunch of clips you want to throw out there and then be part of the community. And that's another thing about this we've got, we've got a great community feel like we have a Facebook group for members where it's the least toxic Facebook group I've ever seen. It's almost too nice. And everybody is so cooperative and supportive and is getting into the spirit of what we're trying to do. Because it's black box is not a doggy dog world. It's a place where we're all in it together. And when we when when one person succeeds, everybody succeeds.

Dave Bullis 1:14:32

You know, and I'm going to link to all that in the show notes everybody, and I'm going to check it out. I am dead serious Pat. I also want to check out this non toxic Facebook group because I have one myself and I keep it I'm the moderator so it's always kept non toxic but I've never seen anybody else have a non toxic facebook facebook group because usually the voids into something and funny enough it's usually screenwriting Facebook groups that go bad. And I've seen the fights that I've seen everything else man um But, you know, I was going to ask you, where can people find you online, but you, you know, you know, I will make sure to link to that you You already gave the URL, but I I'm gonna link to that and everything else. We talked about everyone in the show notes at Dave voices.com. Pat, I want to say thank you so much for coming on. Man.

Pat McGowan 1:15:19

It's been a real pleasure. Know, you're a great interviewer. So thanks for that. Thanks. You know, thanks for letting me talk about black box.

Dave Bullis 1:15:27

Now, my pleasure, Pat. And you know, let's talk again real soon.

Pat McGowan 1:15:31

You got a brother. Thanks a million.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

LINKS

- Pat McGowan – IMDB

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Filmmaking or Screenwriting Audiobook