The movie ‘Mad Max: Fury Road’ is one replete with actions, blood, and gore. It tells a story of how a vicious and tyrannical leader Immortal Joe is relieved of his secret harem containing five beautiful princesses.

These princesses were kidnapped as children and kept as breeding machines for Immorta Joe. However, his most trusted war leader, Furiosa, betrays him by carting away with his prized possessions. Furiosa, the warrior woman, tries to take the women to her childhood home -the green place- where she was also kidnapped. The road to ‘paradise’ is fraught with danger. There is no hiding place as Furiosa, her side kick, Max and the women try to escape the tyrannical warlord. An angry leader who is hard on their tail along with thousands of fierce armed warriors whose only rule is to kill the betrayer and return the harem unharmed.

This reverting movie has a lot in common with comic strips and superhero films. It uses explicit scenes to portray the plot. The film was created mostly from the story boarding style of about 3,500 different comic books. The writer George Miller, and his artists worked for two years, tirelessly building the action in drawings before adding any form of dialogue with the story board. ‘Fury Road’ is majorly created through art and sketches. If you view most of the scenes in the movie alongside with the story board, it would seem like a comic book adaptation.

To prioritize the images or visuals of the film, George Miller lets his characters speak only when necessary. Meaning, the movie is all about action and less about dialogue. Unlike conventional movies where dialogue is used to paint pictures, Fury Road is the opposite. The film uses images to replace words, a nuance employed in comic books. Even Miller’s story board contains no words at all.

Another way Miller has been able to make this movie otherworldly is the unusual names he gave his characters. The names like Furiosa, Immortal Joe, Nux, etc., make them seem unreal, almost like they are their alter egos or aliases just like how comic heroes are.

He portrays Immorta Joe as a villainous character who aims to deny his people of natural resources. Making them beggarly, diseased, and dependent on his benevolence. His minions are kept loyal, with a ridiculous promise of an afterlife that rivals paradise and fear of retribution if they disobey him. Just like the evil villains in popular comics such as Spider Man.

Mad Max: Fury road relies heavily on the elements of a superhero movie or a comic book even though it’s neither. But, it just as well might be seen as the best of either cadre.

It is said that the movie Mad Max Fury Road has finally been made into a comic strip to the delight of its fans. The influence of storyboarding in this movie is epic.

If you are new to directing and need a better understanding of shot selections, storyboard and what they mean to your storytelling process what the video below.

There’s a storyboard template to fit any creative desire below. Happy filmmaking!

Spoiler

Storyboard Template

Another choice when it comes to angles is also the question of, are you going to show an upshot? Where you don’t see the ground at all because you’re just looking up into the sky or are you going to show the down shot? And you not be asking yourself, okay, Sherm, what is it, which do I want to show? Well here’s a good part is you get to choose and the whole point to choosing, is that as long as you have good reason for what you’re going to be choosing. You’re probably going to be doing the right choice.

Here is what I’m talking about. If every one of these choices has meaning behind it and usually it has to do with that camera being representing us and our attention. And so if you imagine that your story involves somebody walking up and looking of a tall building, that’s going to be part of the story. For example, let’s say this guy is fresh out of the sticks he’s and never been to New York City before. He’s looking up at giant building.

Well that story is going to tell us something, that’s just going to, we’re probably going to want to draw something like this, which is from his vantage point or his P.O.V, which is his point of view. What point of view does is it’s really the heart of getting us as a viewer to identify with character, because if we identify with the character then what happens to the character on the screen is going to matter to us. And that again is just the heart of making that connection with the viewer. So this choice of angle and composition is really, really important for getting an emotional involvement with the viewer.

So again the beginning, when we’re talking about cutting, we’re talking about we need to choose what to shall and that’s pretty much just information. We haven’t decided yet how we’re going to show it, but an angle composition, we’re talking about now how to show it. And we’re getting more into the character of more into their point of view. For characters using up shots and down shots quite frequently if you have two different sized characters in a show. When they’re talking to each other, this character is generally going to be looking up at this character.

And this character is generally going to looking down at this character. So frequently your characters are going to be drawn in up shots and slide down trust pending on their size. Well, a lot of people get really thrown when they try to draw up shots of characters. For example, they may try to draw the underside of her nose and have difficulty with the character’s features drawing from such an unusual angle, and for example you can see the ceiling and the walls of the room. And what I wanted to show you is that frequently, especially with animation.

These kind of up shots can be done much more simply despite implying the upshot using the background. So if your character normally looks like this in a three-quarter view from straight on, just by adjusting the background a little bit and showing that same ceiling. You have a slight upshot, but without the weirdness that can come with trying to draw on upshot, a character that hasn’t really been designed for that.

So this right here is something that could save you quite a lot of time and trouble because generally you’re not going to have that kind of extreme angle where this one will read just the same. The same will follow for another character if you’re working in a down shot. If you have a little character like a mouse, very frequently you’re going to be looking way down on them, well you could spend a lot of time trying to figure out what he looks like from that position, but he’s going to look probably pretty weird and pretty off model.

So again, it’s just as easy, and you’ll see this in a lot of kind of cartoons that have these sort of characters that you can just draw that same character from more of a standard point of view, but still show the floor to represent a down shot. This is a total miracle when it comes to trying to draw characters on model.

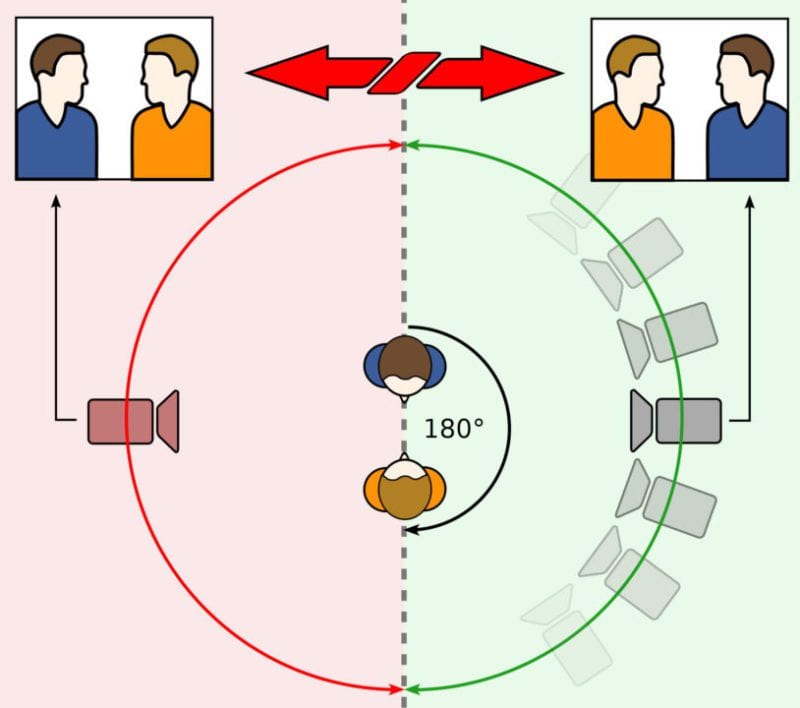

I’ve just seen so many people struggle and struggle with this, because most model sheets that animation will show you is going to show characters from pretty much a straight on view, but in 360 degrees. Again even if you’re work on live-action. These kind of shots could be very difficult to draw. Drawing up shots on characters and down shots tend to be a lot more challenging and if you’re wanting to just get a convincing shot that reads very clearly, you can just use this technique of manipulating the background.

So again that is for down shots and up shots and again this has to do with who’s mind it is that we’re getting into. So when we see this sort of shot, the viewers aren’t thinking about it very much, but they are going to get the feeling subliminally that they’re looking from a low point of view, because we can see that ceiling. You might even put a little, it might be a little lamp up there.

There might be other background elements, like a picture frame or maybe a lamp on a table. Regarding composition, I would also stress that other decorative elements like that when put into a background are there to still support the scene, background design is one of many things that you’re going to have to deal with and an artist that draws flat or unconvincing or cluttered backgrounds are just going to have a difficult time getting people who like their work. So this is kind of arrangement of background details that you would want to have.

And even if you really look at the schematic of this room and you thought oh no you know what that light, that light should really be here and there’s a chain hanging down like right there. Well these kind of elements start touching and tangent against the main character will really start to distract the viewer and they are totally distracting. And we’ll talk about this other topic of tangents.

Today we are doing storyboarding, which is one of my favorite parts. Because you’re making the movie before you make the movie. I absolutely love it. We tried to capture the whole process of making those boards to show you guys so let’s not delay any longer Shall we jump right into it.

So I’m working on storyboards.

Now we’ve been working on it for a while. First, of course, comes a shot list and things like that. And once I have a clear vision of what I want the thing to look like, it’s time for me to board now storyboarding isn’t a completely mandatory thing for you to do. There are some directors who don’t most do storyboard. Some don’t do it before time, like Ridley Scott will board what he wants to shoot that day the day before or on the way into shoot the actual film, but some will board way in advance and get really detailed with it. I’m the type of person who likes to board every single shot in the film.

The reason I like to do this is because I set such a clear plan before time I make my entire film before we ever step on set. And by doing that, it is really easy for me to throw everything out the window when I want to because there’s a clear plan in place, I don’t have to be stressed out or constantly thinking how I’m going to do the next thing I have something to fall back on and this structure to work off of.

So I can really get creative and do whatever I want. After that. So when I bored before, anytime I would do storyboarding before, I was always doing it by myself, I didn’t really have a budget or the network to bring somebody in to help me do storyboarding. And you can do that if you don’t have an artist or you can draw, you can still do your boards or stuff like taking pictures, and making your storyboard through pictures.

There’s an app on iPhone called cinematic, which we’ve talked about on the show before which is awesome and has everything you need to make a storyboard. Just go around your house with your friends, getting the clear idea of what it is you want your film to look like. It’s really, really helpful, especially when you’re working with a crew to be able to just show people not try to explain but actually just show this is what I’m talking about. Another great one is frame forge 3d. That’s an awesome program where you can actually find your shots.

And once you have your shots set up, it also makes camera plots for you. You can do different frame sizes, you can do different lenses, you can also get all the measurements, if you know where you’re shooting, you can get the measurements of the room and build it exactly, you’ll know all the heights of your camera. And what I love most about frame forge 3d is the fact that you can find shots this way.

Like it’s a great thing to just move the camera around this virtual world and find the exact shot you want to come in zooming out, you can really learn different focal lengths and what what they’ll make that scene feel like so there’s a lot to that program that’s really beneficial. But with this one, I really wanted to work with a storyboard artist because I was convinced by Fred Dan that that was the way to go when you’re directing, especially with your first big project working with a storyboard artist, he says is the first time that you direct your film, and I gotta say he’s 100% right, having to give my vision to another person verbally for them to put it down visually, has really helped me I mean, I’ve had to justify shots and the way a scene played out, that made me completely rethink the scene because I was wrong.

Once I was seeing it there. And I was explaining why one moment happened to the next, I found out that this was something I was gonna change on set. And given that we only have a certain amount of time to shoot, we’re having a crunch crunch our days, because of the budget, we got to keep the budget down. But working with so many people to find that issue onset was something like this would really be difficult for the production, I mean, something like tell or losses, that’s fine, we’re there with a bunch of friends, it’s not that big of a deal.

But something like this, I really need to make sure all my stuff is locked down. And when I get on there, I know exactly what I want. That way I have the freedom to move around a little bit if I want to. So having Jordan who is the storyboard artist I used, write, draw up the boards and even give me ideas for things was really, really helpful. They bring out they want it I talked a lot.

There was a lot of explaining but now on day three of boarding, which is, I guess 18 hours into boarding. There’s kind of like an unsaid language happening where she totally gets my style. And now I just kind of get the idea of what the morals but I just watch her rip what’s in my head directly out and draw it into a frame. But again, these boards don’t need to be super detailed.

I mean, Jordan isn’t even spending a ton of time to make this look like a comic book. It’s just what you need to get the detail across of what you’re trying to do. I mean if all you’re doing is drawing stick figures and it still gives the idea of perspective and composition. Well then you have yourself a storyboard and I think it’s really important especially when you’re shooting a film. Because you’re shooting completely out of order, you’re all over the place. This helps you retain your original intention of what you wanted for that scene what you wanted the camera to do.

Because in pre production, you have all the time in the world to really dive into your script and figure out what you want your audience to be filming, when you’re on set, it gets really stressful. And it’s really easy to forget where you’re at, under that sort of stress. But with a storyboard, you can easily just go look at the image. And it all comes right back to what you originally wanted for that scene. So it’s really a kind of a safety net, to ensure that what you originally wanted, is still going to find its way to the film.

Another thing that I thought was interesting that I hadn’t thought of before was the actual location we started boarding before I found my locations. And once I found them, we actually redid a few boards, because I had to redo my shot list based on the location, some things when it worked, then I was able to show my artist, some images of our location. And she started tailoring her images to what the location actually looked like, which was really going to help us once we’re there, we know exactly where I wanted the camera, originally, thanks to the storyboards. And it helped us see what we were able to actually do with the camera and not since we know what sort of obstructions are actually in the scene.

Now if you can’t see the location first, it’s really not that big of an issue. The storyboard is still going to help you to know what sort of thing you want. And so you can easily rearrange your shot based on the location you have still getting all those ideas and punctuations that you had in the storyboard. So here’s how it worked. First of all, how did I find a storyboard artist? Well, I just searched the internet, I googled storyboard artists, and then around my location, and I spent days looking for people that I think would be down to do it, that wouldn’t cost a ridiculous amount of money, what you can do is look for people in art school, if someone’s actually still in college, they’re going to be down to do your project desk, just to have a credit just to get experience, it’ll probably do it for free. Of course, it’s nice to give them any amount of money you possibly can. But most of these people in these art schools will probably just hook you up for free, and they’re going to be very, very talented people.

Now, when I met up with Jordan, of course, we start going through the boards one by one starting from our first shot. And I actually went through the script in chronological order. So jumping from scenes back and forth, so I could kind of see my movie layout in front of me, I would describe the shot and draw very, very poorly on a notebook to try to express what I’m trying to think of what’s one thing that helped us a lot was doing Google Hangouts, since I’m in pre production, I couldn’t meet that much. So we would do Google Hangouts, and you could do a screen share. And I was able to show her my screen with frame for Janet, and then position the camera to kind of kind of give her a general idea of what I wanted to do.

And she could go off that. So frame forge really helped me out there too. So the first thing she does is thumbnailing, which is just these really basic, really sloppy images to where only her and I can really tell what that is, then she’s gonna take that back, and then she fixes it up to the second round of roughs. This is a lot more intelligible, you can tell what you’re looking at, it gives me a clear idea of where the camera is perspective and angle.

And then once I approve all those, or have corrections, move up, move down, left, right, I’m very picky about because I want everybody to know exactly what I wanted, she goes back and she makes the final boards, including shading and everything else that really captures the tone for the rest of the crew to see, which is why I’ve been really loving using an actual artist. Because not only is the angle that I want in there, but the actual tone is being represented for people to be able to see there’s also a side to storyboarding that’s kind of like screenwriting. Whereas screenwriting, there’s a secret language to it, that formatting kind of shows someone that the person writing knows what they’re doing, since their formatting is correct, well, storyboarding does have something similar to that. And that is the way that it shows how a character is moving or the cameras moving in and out.

So the usual way that you show the different camera moves is just drawing arrows with usually the cameras written inside them. But for something like zoom, you want to show like the zoomed out version. So this larger frame is where it starts. And the smaller frame is where within and then just draw on the arrows to show the direction of the zoom. So for the reverse zooming out, you do the same thing, you show where it starts. And then you show where it ends, these chunkier arrows are usually what you use for camera moves, there’s like, as you can see, there’s kind of an infinite amount of shapes that you can have the four character moves, what you want to do is use these like skinnier arrows, just so you have a difference between the two. And you can tell what, what the arrow is talking about. So if this guy is going to move this way, you want to draw a little arrow that’s going that way.

I mean, really, what a storyboard is going to do is keep you on track. Like I said, when you’re on production, it’s a little bigger, more than you’ve ever handled before. And it’s crap hits the fan, you start getting crazy stressed out, this is going to help you keep in mind your original intention of what you wanted, and get everybody else on the same page with you. Now if you’re looking for a storyboard artist, you could always use the storyboard artist I used you she can be found right here. She’s incredibly talented, and she’s not going to rip you off, which is nice.

She also has a Twitter right here that you can follow and you should follow because she is quite talented. But that’s it for today. I hope that was helpful to you guys. And of course, again, if you don’t want to draw the thing you can use frame forward, you can use Cinemax, you can just use pictures if you want however you want to do it. Just the idea is to put your vision on paper for you to keep in mind and for everyone else to see. But now, back to the rest of this pre pro and I’ll see you guys next week.

You know, when it comes to camera angles in framing, the full shot or full body shot includes the feet and the frame. For this type of shot, remember to never cut off just the feet. In fact, it’s bad practice to cut off your subject or your knees and below, made look like you basically did it unintentionally or by mistake, like you can see here. It also just looks awkward when the person’s legs are cut off below the knees. Now this, in fact, is not a rule by any means. In fact, I don’t really think there are any rules and film.

But it’s just, you know, bad practice. If you’re going to frame your subject like this, then you better have a good reason for it. Otherwise, it will just confuse your audience and will just simply look like you don’t know what what you’re doing. So basically, for full body shot, you should, you know, stick to something like this. next shot is a medium full shot, that’s when you go in a bit closer, and it’s usually also when you cut off your subject somewhere in between the knees and the waist. And once you frame up above basic the waist area, that’s called a medium shot.

After that, we move in for a close shot that frames from around the breast area and app. And then this here is a close up view which basically frames mainly just the subjects head. Once you move in even closer where you start to cut off the forehead or the chin. That’s usually referred to as an extreme close up, even once you move in to just frame the eyes, for example. Now what you got to remember is that there is no standard by which to go when naming these types of shots. These are simply the names that I use.

There are others out there that use different names. What’s important is that you know what type of shots you want to get. So you know, when you’re planning your shots or doing your storyboards, you always use the same names for the shot type. So you basically don’t end up confusing yourself later on down the road when you go back to look at your notes or your storyboards. And next we’ll talk about the types of shots or angles like over the shoulder or a two shot. These are most commonly used in a scene where two characters are talking to each other.

The shots refer more to the angle than what the exact framing is, for example, you can have a close up over the shoulder or a medium over the shoulder like you see here. And you can even go to a full body over the shoulder. Same goes for the for the two shot. Here we have a full body to shot and then a medium to shot. And then a close up to shot.

Or you know you can also have a three or four shot or whatever and and depends on how many characters you have in your shot. Other shot types you might hear about are an insert or a cutaway, which is basically a close up on a part of the scene or you know, could be a POV of one of the characters we’ll be seeing basically a certain detail in that scene like we see here, where one of the characters passes the car keys to the other. And many times people ask me what size lens should they use to get, for example, a good medium shot?

And really, there is no one correct answer. The types of shots or the framing really have nothing to do with the lens. For example, you can have a medium shot that’s shot using a wide angle lens, such as this 16 millimeter Canon lens that I’m using here. Or you can have a medium shot that shot using a 50 millimeter lens.

Same if you use 100 millimeter or even a 300 millimeter telephoto lens. They all produce medium shots. But of course, each of those lenses gives that shot a different look and effect. The framing doesn’t change. It’s just a perspective. So remember that shot framing has nothing to do with the lens size. And the only way you’ll ever really know what type of lens to use in your scenario is once you have a lot of experience going out there and filming, you know, just trying out different types of lenses and experimenting, then you know afterwards, you should come home and compare what kind of effects you got using various lenses on different types of shots.

Because there’s virtually an infinite amount of effects that you can get when you’re mixing up different types of framing, shot types, angles and lenses. For example, let’s take a close up and do a few versions of it and see what kind of effects we can get. If we were to use a mid sized lens such as this 50 millimeter, then you would get something like this, you know an average type of kind of looking shot.

But for example, if you’re filming, let’s say a comedy and you want it to show a person you know in a funny way, then it might be better to go in and real close and use a wide angle such as the 16 millimeter lens, which will make your subjects features look a bit distorted or exaggerated. It’s not actually the lens that makes your subject look that way but your relative position to the subject.

Basically, the closer you move to subject the more dramatic the perspective will be. But obviously you got to use a wide angle lens when shooting this close. Right now we’re about two feet away from the subject. Now if we were to use a 15 millimeter lens at that same distance, then the perspective doesn’t change. But the framing obviously will, because we’re basically just zooming in. So all you end up seeing is this, it will be the same view look at this shot that we got using a 16 millimeter lens, and then digitally zoomed in. The only difference being that the depth of field will be the same as the 60 millimeter lens. And of course, we end up losing a lot of the resolution, which is why we use different lenses.

Or if you’re using a camera that doesn’t have interchangeable lenses, then you would simply zoom in or zoom out. Now let’s take a look at a full body shot. To get it with a 16 millimeter lens, we have to move away from the subject a few more feet, if you were to move away from your subject to about 250 feet, and this wide angle might be good if you’re trying to get let’s say a wide shot of the location.

Because your subject is so small that it’s really hard to even see him. So that’s when you do want to use a long lens such as this 300 millimeter to basically zoom in. Now when you’re this far away, that’s when the subjects will look more flat and less exaggerated. Since you’re seeing all the features from pretty much the same perspective. It will also bring other surrounding objects such such as this mailbox that we have there in the background, closer to our main subject.

Whereas if we were you know, a bit closer, and let’s say using a 50 millimeter lens, it looks like that mailbox is a lot further away. They’re both the same types of shots, a full body shot, but what changes now is our relative position to the subject. And since with the 300 millimeter lens, we have to move away so much further. And then zooming optically, we end up also zooming in on the mailbox, which is why it makes it look like it’s basically a lot closer to our subject. And then for example you can see in this full body shot that we got using our 50 millimeter lens.

So anyway, next time you’re wondering what lens you should use in your setting, just simply go out there with your camera test all different lenses experiment, and above all, just have fun, because that’s really the best way to learn.

In the logo, you know, I feel like every time that I look up storyboards and how they’re supposed to look, they always look really nice. And I used to think that to do them properly, you actually had to be a good artist, which I am the exact opposite of, which I guess is just a bad artist. But today I’m going to show you the basics of doing storyboards and show you that I can do them, anyone can.

storyboards are done so that you can visualize your film scenes before you actually shoot them, which is a huge help to have on set, it makes your life so much easier, it’s a lot harder to forget to get a shot or you know, not get coverage or a certain insert shots that you wanted to have. And you just forgot while you were on set, it’s a lot harder to do that when you have a good visual reference on set.

And you know what the final product needs to look like. And there are some amazing storyboard artists out there like really good to the point where you feel like you can already see the final look of the movie when you look at them seriously, really amazing people out there. But if you’re like me, then you are not one of those people. I mean, this is how I drew Griffin. It’s like a preschooler with not a lot of talent.

But you don’t need to. But you don’t need to be really good at drawing to be a good storyboard artist. The important thing is that you can interpret what you’ve drawn, and that you can effectively translate them into the images, you want to demonstrate just how bad an artist you can be and still make this work. I’m going to use a few very quick excerpts from the short film script that I’ve been working on and no laughing all No.

Now, as you can see here, that’s supposed to be the cabbies head in the foreground, that is William in the mirror, those are supposed to be the buildings that’s supposed to be the street. So as you can see, I’m not very good. I just make it so you can identify the characters like I know that that’s William in the backseat, because of that really well drawn cowboy hat that’s on him. It’s pretty still shot.

But alongside your storyboards, you can add notes that tell you things like the lighting in this case, I wanted Williams faces and shadow now I already sort of shade it in his face to get that across. But just so that people understand that if they look at this and can’t quite understand what I’ve drawn Williams face and shadow except for brief flashes from exterior light. You can also say the action that’s supposed to take place cabbie, adjust the mirror, I’m not drawing a really bad arm reaching up. But you know, it will be understood that that happens in the shot.

Here’s a line from later in the script. Now he kind of does the dramatic turn back like and says line. Now if you want to show on screen movement, you can use arrows within the frame. In this case, I’m showing that his head is turning around but not his body. You can use this for anything, you can use it for walking, you can use it for any small movement that you feel you can animate just using an arrow, you can do that.

Now on this shot, I also want the camera to push in. Now I could draw a second closer picture to show that that’s what I want to have happen and then just label it accordingly. Something I’m going to show in just a second. But in this case, I can show that the camera needs to push in just by doing this, I’ve drawn what the final framing will be these arrows here show that the camera will push in that just to show that it’s a push and not zoom again down in the notes camera pushes in from medium to close up.

Now I’ve got the shot where the car full of the thugs is driving up slowly. And they’re all looking away from the camera out of the parking lot and the building in the background. Looking for a particular car. Now I drew the worst car ever. But for the actual framing, I wanted it to be tighter. So I’ve adjusted the frame accordingly, you can actually draw the rest of the picture and just keep the frame for visual reference as to how it’s supposed to look when it’s shot. And again, I want the camera to move. But this time I’m not, you know pushing in or zooming in. But I actually just wanted to track along with the car. This is easier to get across if you use arrows that kind of crossed the line from outside the frame into inside. And in this case, just for reference, I’ve written track, that is pretty simple. Drawing a car is not as simple for me.

Now this is if you have one long shot, but you want to show multiple frames to show what the action is going to be. This one is going to be a shot that starts off on the ground showing the door of a car opening the legs stepping out of the camera pushes in and raises up and shows the character of William they’re raising his gun and about the fire. Now as you go through your storyboards, you should number them. And if you have multiple frames for the same shot, you just label it one a or whatever number a than B and C etc. And that’s just a few brief storyboards for me but they’re good examples of what you can do when you really can’t draw. But you do have other options if it’s a quicker shoot and you just sort of quick notes on how things need to look.

You can actually do small thumbnails in the margins like this one here, which was just going to be a two shot of the two characters in the cab and I didn’t need to do anything fancy. I just show the two characters are sitting alongside each other face in the camera. That’s the framing, nothing fancy but it’s good to have on set if that’s all you can do. Some people don’t like to completely visualize that they just like to make a shot list. They have a list of shots that they want to get like extreme close up, insert and master shot and they’ll just in writing describe what they want.

And those can also be put in the margins there also pewter programs that you can use that you can make digital art storyboards. And there’s quite a few out there if you don’t even want to touch pen and paper. And it doesn’t always have to be as messy as what I’ve done here. So if you want to look a little bit more professional, you can find templates for storyboards, and shot lists and all that online. And that’s really it. For me, again, I’m not good at this. I’ve said that 100 times at this point, but you don’t have to be, you just need to be able to translate your images to the screen.

And when we actually start shooting the short film, we’ll come back to the storyboard and see just how well I was able to capture that. And another thing you can do that Robert Rodriguez actually does is that you can actually just go on set with a camera and just sort of video storyboard with your actors, have them stand in their spots, get an idea of what you want it to look like and just leave it at that. That’s one of the videos we’re going to be showing in the playlist at the end here is a little featurette on how he does his video storyboarding one video I couldn’t find anywhere online, unfortunately.

But if you have the seven DVD you should check it out. There’s an alternate ending where all they had was the storyboards and they had actors do voiceovers and they sort of animated it, which is called an animatic, which is a whole other thing for another episode.

I know what you’re thinking Mad Max, a comic book film. What enough is this guy talking about? Well Hear me out for the entirety of this video and then just maybe you too will see how Mad Max Fury Road is an unconventional comic book film. Everything that we’ve seen on screen and Fury Road is largely practical effects. We’ve all heard the story about how George Miller and his crew wanted the film to feel tangible and truly kinetic and energy. But what if I told you that 80% of what we see on screen was recreated from 3500 panels of comic book style storyboarding?

In fact, take a look at this. And now this, Miller and his team of artists worked tirelessly for two years drawing out the entire film before even putting any dialogue to paper. It’s important to note that these are genuine panels almost as though they could be printed instantaneously and passed off as comic books for many films on the go to storyboard process.

Very few do so without actually knowing the dialogue they are working off Fury Road was conceived through art and sketches. And if we continue to view the side by side shots of the panel and then the film, it almost feels like a pulpy comic book adaptation, something similar to this perhaps. From an artistic standpoint, the whole visual and feel of Mad Max would not look out of place if say, US DC or Marvel logo slapped in the opening credits of it. In fact, Fury Road is the greatest superhero film of this decade.

Because yes, let’s face it, this is eerily reminiscent of the world of a superhero. And it all starts with Furiosa. Our protagonist could easily be compared with Batman, for example, her parents of dad she rose this vast world alone and effectively by the end risks her life to better and protect that of the people around her. She even has a trusty sidekick, Max. that camaraderie and short could be conversations but yet another strong facet of this forms layered comic book style nuances. While the dialogue is minimal. This only adds to the sheer hilarity and sometimes cheesiness of it all.

Mila himself had this to say about the dialogue, or something which was pretty nonverbal. I mean, people obviously speak in the movie, but they speak only when it’s necessary. And I think that quote is super important, especially as it’s a way of prioritizing the images as vivid replacements of words. There’s the often spout cliche in screenwriting, where you can paint a picture with words for Fury Road almost subverts this, as this pictures evoke words. Instead, the minimal dialogue has its roots deeply ingrained in the comic book style, with Miller storyboards, even after the script containing zero words. Another little nuance which solidifies Fury Road as a somewhat unconventional comic book film is the character names.

They don’t usually feel like real people almost as though these are their aliases. alter egos. Furiosa max rocker tans be immortan Joe slip knocks, the list goes on. And the comedy for he’s pretty awesome.

It almost establishes an idea of hierarchy as the longer name characters are often the most powerful. Meanwhile, those with shorter names are more expendable. The names alone concoct this world that feels as though it exists in a realm of imagination. Get the images much like Gotham and Metropolis remind us that this is a world like ours where if something goes wrong, we could very well end up inhabiting it’s almost cautionary in a way I live in comparison. swampthing in the both deal with nature and the environment as a rustling of society.

The point here is in the Mad Max is ripped off these comic book arcs or films, or was even influenced by them, but it’s simply a fun anecdote that helps this action epic operate as a quasi comic book film. On the topic of characters Fury Road also delivers the brutish villain in in Walton Joe, a man hungry for water and oil depriving everyone of natural resources for his own presidential like power is cold season Come on the wall boys into giving up their lives for him if need be. In return, he promises them a birth in the afterlife of Valhalla.

We’ve seen this type of manipulative and power hungry villain and the likes of Green Goblin and many Spider Man arcs or the Joker and His endless band of goons, the myth and legend of immortan Joe makes him as compelling as the best comic book villains to even has that stereotypical muffled voice of the comic book villain like say Bane, for example.

And as a side note, Fury Road has recently been turned into an actual comic book series. It may not explicitly be a comic book or superhero film, The Mad Max Fury Road toys so heavily with elements of the two that it might as well be and if it constitutes as one then it may very well be at the top of many lists as the best. Hey guys, I’d like to thank you all for watching the video.

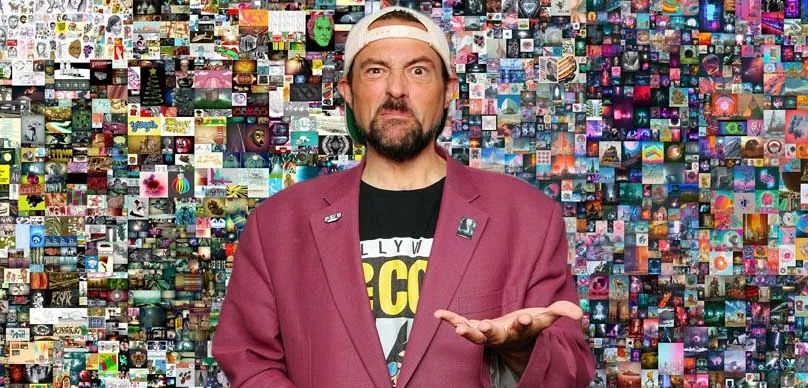

Storyboards are illustrations that represent the shots that will ultimately make up a movie. They allow you to build the world of your film before you actually build it. There are any strict exacting rules on how to do storyboards conveying information is what’s important. storyboards are ultimately a technical document a tool. So it doesn’t matter if you’re a skilled illustrator or not. This can work just as well. Is this a way they could take care of? Yes, no problems. I’ll put them on my cat.

Even if you struggle with the perspective or can barely draw a stick figure you can still convey what types of shots you want and their basic composition. Who storyboards typically, the director sits down with a storyboard artists to help articulate their vision. However, it’s not uncommon for cinematographers and production designers to join in the process as well.

I usually meet with the director and produce rough thumbnail sketches that summarize the important information each panel and then afterward I’ll fill in the details on my own meeting with the director once again after completing the panels to make sure everything works. Well then share the completed panels with the rest of the team. Let’s break down the parts of a storyboard.

The panel or frame is a rectangle that represents what the camera will see. panels come in a bunch of different shapes. Pick a panel shape that matches your shooting aspect ratio square widescreen, really really widescreen. A person drawn really small on the panel is a wide or establishing shot. A big head taking up half the panel is a close up. You’d like them. deciding where you put the person your frame is the basis of your composition. This may seem really basic, but this has a huge impact on how you prepare for your shoot these illustrations give your cinematographer a starting point things like camera angles, lighting, depth of field the whole gamut of decisions can be informed by the storyboards.

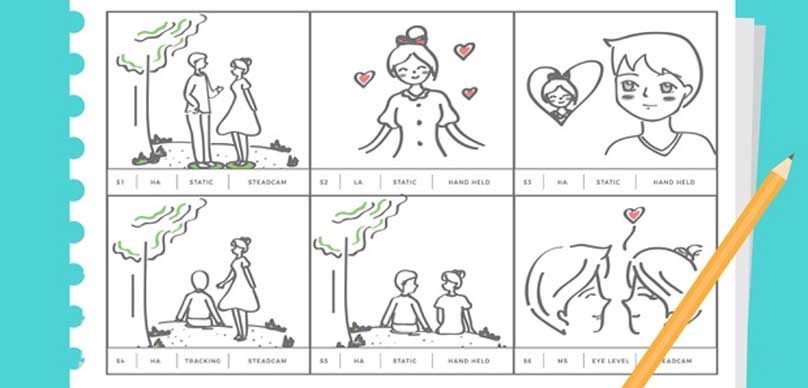

It’s also a great way to decide what you’ll need out of your locations. Do you really need a giant bottomless pit? Or can you get away with one visual effects wide shot and then cover the rest and tighter shots? Okay, let’s talk about arrows. So now that we have a panel with a character in it, let’s say that character is moving to the left by dragging an arrow pointing to the left we show where that character or door or dinosaur is moving. There’s no real rule to drawing arrows and everyone has their own personal style. But what’s important is that your arrows are easy to read and make sense.

Here’s some examples of arrows. Arrows for characters moving towards camera arrows for characters moving away from camera, this character is kneeling down, and this character’s head is falling off. Arrows within the panel usually mean a subject is moving in the shot arrows around the edges usually imply some sort of camera movement. So here the Raptor lenses right, and the camera pans left.

Now let’s talk about camera movement. camera movement. Arrows also aren’t really standardized, but let’s go over some common ways camera movement is illustrated. Dolly movements are typically done with one arrow often narrowing a little bit to suggest movement in or out of 3d space. Both Dolly shots and zooms can also be illustrated by placing arrows in all four corners of the panel. This shows a widening or narrowing of perspective, you can draw a panel within your panel to show how far your dollar zoom goes.

Clearly conveying information is key. So it’s better to over explain than to confuse people. Hands are often shown with an arrow on the side of the panel, either pointing to the left or to the right tilts up and down are done much the same way. Except with the arrows at the top or bottom of the panel. You can also elongate the panel to fit the entire shot in a single drawing.

Since this can get a little confusing, it’s okay to make a note indicating whether or not the shot is tracking versus panning or dollying versus zooming. Because arrows are often used the same way in both instances, you can make your notes beside the panel or in the arrow itself. Sometimes you’ll need more than one drawing to illustrate what’s happening in a single shot, especially if it’s a really complicated action or camera movement. When you take panels with angle composition on screen movement and camera movement, and then combine these panels into a sequence, you have the foundation of your movie

storyboards are pretty Pick really useful for preparing scenes that require multiple effects techniques.

For the scene from truck flipper versus bus puncher, we use storyboards to decide what was going to be stunts, what was going to be practical onset special effects, what was going to be green screen and what was going to be CGI based on exactly what kind of action was needed in each specific shot without planning ahead. A scene like this would have been impossible to shoot in the amount of time we had available. storyboards are typically created based off a completed script. But if you’re doing a story that’s extremely visual storyboards essentially can be your script like with Mad Max Fury Road.

Since it’s such a visual film, the beats were more effectively planned out with pictures than with text on a page. While this is an extreme example, this holds true for preparing all visually complex scenes. There’s also plenty of other alternatives to storyboarding, Stanley Kubrick used actual photos from his location scouts to find his compositions. It’s also worth mentioning that filmmakers who’ve adapted comics and graphic novels often use the original artwork essentially as storyboards for the final film, you can make animatics of your sequences on your computer to include motion and timing. You can also videotape your prevas which is really useful for complex action.

You don’t need the actual set costumes or magical flying speeder bikes to test out your ideas. In the original Star Wars, George Lucas used real world war two documentary footage to help pre visualize the space battles headache.

Animation has also been used to help capture complex sequences, Jurassic Park, you stop motion animation to pre visualize the dinosaur scene. When the decision was made to use CGI in the final film, they had already planned ahead and painstaking detail and knew exactly what specific movements the CGI was going to need to be able to do.

By the time Peter Jackson did the Lord of the Rings trilogy, digital technology had developed to the point where they were able to motion capture the cave troll sequence, and then move a digital camera around in 3d space to pre visualize the entire scene in a virtual setting. There’s no hard and fast rules are one way to do it. But the ultimate goal is planning and clear communication. So whatever tool is going to help you prepare and share your vision the most use it it’ll pay off when you get to set and will help empower you to make the best film possible.