Right-click here to download the MP3

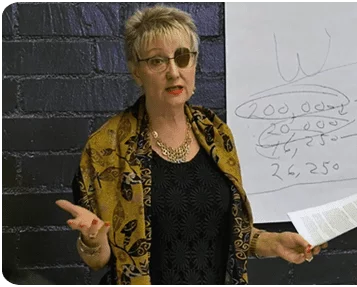

I am a huge fan of today’s guest. Since seeing one of her first documentaries, I was transfixed by her power of storytelling. Our guest is an Emmy and Peabody award-winning documentary filmmaker, Lynn Novick—a formidable and respected PBS documentary filmmaker with thirty-plus years of experience in the business.

Her archival mini and docu-series documentaries bring historically true events to the big screen alongside her filmmaking partner, Ken Burns.

You’ve most likely seen some of her landmark documentary films. The likes of Vietnam (2017), TV Mini-Series documentary The Civil War (1990), College Behind Bars (2019), eighteen hours mini-series, Baseball (2010), and many more. All are available on PBS Documentaries Prime Video Channel.

Just this year, the pair premiered their latest co-produced and co-directed three parts documentary on PBD—recapitulating the life, loves, and labors of Ernest Hemingway. The series explores the painstaking process through which Hemingway created some of the most important works of fiction in American letters.

Novick is an experienced-learned documentary filmmaker. In the mid-1980s, she applied to film school but did not pursue that lane when she couldn’t find a documentary filmmaking-specific program. Instead, she sought out apprenticeships. Starting at the PBS station in New York City WNET, for six months. And then worked for Bill Moyers as an assistant producer on a series of projects, including her debut production in 1994 with Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth, followed by A World of Ideas with Bill Moyers, etc.

The Civil War is a comprehensive survey of the American Civil War.

Novick’s decades-long collaboration with Ken Burns emerged in 1989 and has led to the co-production of a number of renowned docu-series. First, there was the highly acclaimed ‘The Civil War’ which traced the course of the U.S. Civil War from the abolitionist movement through all the major battles to the death of President Lincoln and the beginnings of Reconstruction.

Her vast experience as a researcher comes in handy on these kinds of projects, she explains during our convo.

She won an Emmy Award in 1994 for producing the Baseball documentary and won a Peabody Award in 1998 for her co-directing and co-producing of Frank Lloyd Wright‘s documentary.

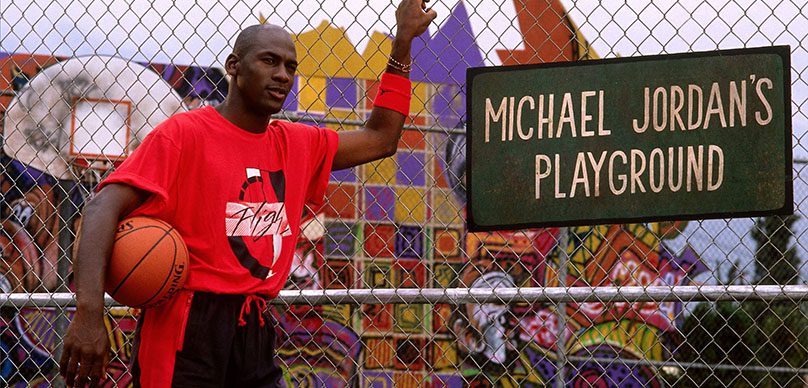

Baseball covers the history of the sport with major topics including Afro-American players, player/team owner relations, and the resilience of the game.

Other must mention include multi-Emmy nominations documentary ‘Prohibition’, The Vietnam War, Jazz, and Novick’s first solo directing, College Behind Bars (2019).

College Behind Bars explores urgent questions like What is the essence of prisons? Who in America has access to educational opportunities? Six years in the making, the series immerses viewers in the inspiring and transformational journey of a small group of incarcerated men and women serving time for serious crimes, as they try to earn college degrees in one of the most rigorous prison education programs in America – the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI).

Novick is one of those filmmakers who have combed through an obscene amount of knowledge and understanding of documentary films. I have a feeling you will enjoy this chat as much as I did.

Enjoy my conversation with Lynn Novick.

Alex Ferrari 0:15

I'd like to welcome to the show, Lynn Novick. How you doing, Lynn?

Lynn Novick 0:19

Great. Thanks so much for having me.

Alex Ferrari 0:20

Thank you so much for being on the show. I am a big fan of your work. I've seen many of your documentaries over the years, I've gifted many of your documentaries, especially to to my father who just devoured baseball. And other things like that. And jazz. I know you were part of those projects with Kenya, as well. So and I dying to ask you how the hell you do these things. So before we get started, how did you get into the business? How did you get into being a filmmaker?

Lynn Novick 0:52

Sure. Well, first, before I get started, thank you for having me. I'm a little bit subconscious, because I had some dental work, and I'm missing a tooth. And so anyway, I asked your forgiveness about that. But it's a temporary situation. So there you are

Alex Ferrari 1:02

in there it is, in looking in the world that we live in a missing tooth is very low on the priority list of things that could happen so anyway.

Lynn Novick 1:20

Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 1:21

in the grand scheme of things, the way the world is working, a little bit of dental is, I'll take that over the worst things that could happen to you in today's world.

Lynn Novick 1:29

So for sure, especially nowadays, my goodness, yeah,

Alex Ferrari 1:32

exactly.

Lynn Novick 1:32

Minor nothing. Yeah, exactly.

Alex Ferrari 1:34

So how did you get it? Yeah.

Lynn Novick 1:36

So you know, I was, I would say, if I look back on my trajectory, such as it is, now it didn't, wasn't clear to me when I was first starting out. I didn't know what I went through. When I got out of college, I was very kind of lost. And I actually saw a number of documentaries, both on PBS and in the movie theater back in those days, which is in the mid 80s. That made me think, wow, you know, I don't really know what I want to do with my life, I might go to law school, or maybe I'm gonna be a professor, I really didn't know. And I just was so transfixed by the power of storytelling, true stories on a big screen based on history and things that really happened. And I love photography, and I loved history. And I just thought maybe I could do that. No idea how or what it would involve. And you know, if a film is well made, you really don't see the effort. It's like the swan going along, and you're just gliding on the water, but you don't see the feet, doing all this below the surface. So I had no clue what was involved in making a documentary, or how challenging it can be or how rewarding but I just naively thought I'd like to do that. And I actually applied to film school. And I got in. This was in the mid 1980s. There weren't many programs where I couldn't find any that taught documentary filmmaking. They're all narrative, scripted, based. And so I decided not to go to film school because I didn't think I had the imagination, frankly, to make up stories and to tell them on the big screen. And I really want to tell true stories. So I decided to apprentice myself if I could. And I really did go through kind of an apprenticeship starting at the PBS station in New York City WNET, for six months. And then I worked for Bill Moyers on a series of programs that he was doing at the time. And then I freelance for a while and I kind of each job I had, I learned a little bit more about the process, and different pieces of it that I could sort of master. So archival research, filming interviews, organizing material, writing a script, you know, different aspects of what kind of goes into any particular film. And luckily for me, I did hear that this filmmaker named Ken Burns was working on a film about the Civil War. And I thought, wow, that that's my dream job. And I managed to meet someone who knew someone who knew someone who can, and literally was so lucky that somebody quit as he was finishing the film. And he really needed someone to come in and help finish up the sort of administrative licensing process for all the pictures they used. So I just walked in the door at the right time, I had enough experience to do the job he needed done. And when we finished that, I was looking for another job. We only had a six month job when I first came. And he said, Oh, wait, don't leave. I'm going to do the series on Baseball, and you should stay and produce it. Wow. That was for me jumping off the high diving board. I had never produced a series I didn'y know about baseball,

Alex Ferrari 4:26

like a 38 hour looking like

Lynn Novick 4:31

joking the other day because the original proposal he told me was five hours. It turned out to be 18. Exactly. Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 4:39

So when you work when you work with Bill, memoria, did you work on a power of myth?

Lynn Novick 4:44

I did.

Alex Ferrari 4:45

Oh, my God, you were. So you were there with Joseph Campbell. And we're not there. But

Lynn Novick 4:50

I wasn't there. Actually, when I came onto the project. This is a series of interviews with this incredible philosopher Joseph Campbell about the power of myth and different cultures and how there's, we tell this Same stories in different cultures, whether the Aztecs or the Greeks, or you know the Norse gods, he found these incredible patterns of kind of the human journey he had passed away. Before I came on the project, he was quite elderly when Bill started interviewing him. So they were organizing the material. And my job was to find the visuals. So he mentioned the Aztec ballgame. I had to figure out what are we going to show where he mentioned, you know,

Alex Ferrari 5:25

Star Wars, the Wayne

Lynn Novick 5:26

and the, you know, the Holy Grail, we had to find stained glass that could show sort of he he covered such a wide range of topics. And I was in those days, sending snail mail letters to the far flung corners of the earth trying to get images to show.

Alex Ferrari 5:42

Right, and I'm assuming, how did you get the licensing? Well, I guess the licensing for Star Wars was pretty easy, because you could just start talking to George.

Lynn Novick 5:48

That's what Bill did. Exactly. So the Star Wars, right. So George Lucas was hugely influenced by these works, and this writer. And so that is how the project I believe, got started that Bill Moyers and George Lucas basically agreed that bill would do the interviews of Joseph Campbell, and they had them at Skywalker Ranch. And then George Lucas, let them use the footage, I believe for, you know, some nominal fee. So that that was the organizing principle. And I have to say, when we were working on it, I did not realize how popular it would be. I thought to myself, what did I know who's gonna want to listen to some old guy talk about the Aztec ball game and Hercules and whatever. And it was huge. It was huge. So it was really it was a wonderful experience to see that people really responded to it.

Alex Ferrari 6:31

Oh, no, absolutely. And I actually saw years later, Bill did an interview with George Lucas on the power of myth on just George Lucas's version of that. I remember watching as well, no, I was a huge fan of that. I mean, I've seen that power of myth thing. 1000 times. It's just so awesome. And any filmmaker, any favorite maker listening today should absolutely watch that. Because also the narrative structure that he talks about, is involved sometimes in documentary and documentary work as well. Just the the, because that's life. That's what the myth, hey, it's life in all our lives as the call to adventure, the refusal, I don't want to go take that new job in, in New York. You know, I live in Kansas, and I'm scared, but then I go and the adventures and the tricksters, and that's life. So it is really, really powerful. So I think why it's so popular.

Lynn Novick 7:21

I agree. And I was just very naive. And I just didn't appreciate the power of what Joseph Campbell had to say and how it touched that deep nerve. And people have tried to find meaning, trying to understand our human condition. And the moment we're in and how it resonates with what happened, people in the past, you know, had the same questions that we have. It was it was, I should go back and watch it again. Because I think it also does have some storytelling lessons for, you know, how to put the pieces together so that the story unfolds in the way that people can watch it.

Alex Ferrari 7:54

So I've always been fascinated, because when you can go down this road to make a just, just ridiculous 18 hours. I mean, they're, they're obscene. They're obscene. How long jazz? How long was jazz? jazz was like 10 hours, eight hours, I

Lynn Novick 8:09

think it was more like 20 because it was 10 parts. Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 8:12

expect that going on. So how do you start a project like that? Like, how do you you're not just covering like Hemingway is a fairly large. We'll talk about your latest project in a minute. Hemingway is a man's life. I know you guys didn't, Mark. I'm sure if you did. I know Ken did Mark Twain. And you have Frank Frank Lloyd Wright's poster in the back. So those are specific people's lives. And that's pretty extensive. When you tackle a concept like baseball, or jazz, like the obscene amount of knowledge that you have to comb through? How do you start a project like that?

Lynn Novick 8:45

Yeah, I find the beginnings of project probably the most terrifying, because you don't at least for me, I usually don't know that much about it. So I have a huge amount to learn. And then to figure out well, how does this fit into something that could be on television, people would want to watch. And, you know, I have to say that one of the critical ways that we go about doing this is in collaboration with other people. So our writer, Jeff Ward, who Kent has worked with for longer than I've worked with Ken, he wrote the Civil War script and several other scripts before that. And he wrote baseball and jazz and all the other films Ken and I've made together so he dives into the deep end of the pool. Also, we order a lot of books, we start to read them, we start to take notes, we started to make outlines. And then we also figure out who is a smart people who are experts, in whatever subject, it happens to be, who are they and can they help us? So when the history of jazz it was when Marsalis you know, we went to see him early in the process and said, Will you help us? And he said, Yes. And then he said, here's the 10 people, you should talk to hear the 20 books you should read, and that lead to other people. So we build a kind of a team of people who really keep us on the straight and narrow in terms of what's important to include and what we don't have to include and you know how to understand that A picture that we're trying to tell. So in the start is hard.

Alex Ferrari 10:04

And I'm assuming though, as you're going through this process that, let's say you have a structured outline, and then all of a sudden you read a new book, or you hear something new from a new interview, and you're like, Oh, God, everything's got to be shifted. We got to insert this here. Now. Now, everything has been all. And I'm assuming that's a constant. It doesn't happen once in a project that happens constantly, because you discover new things in your archival or archaeology. archaeological dig, that you going through

Lynn Novick 10:29

Yes. And once the word goes out that we're working on something, people are always sending us stuff, which is so great. So the worst thing that can happen is after the film is done, and then that happening has every project Yes, of course. And it's just you sort of just feel I wish I knew about that two years ago, but what can you do? So you know, but we don't try to be the last word. So new materials always coming out about every subject. And someone else can take up the baton and continue telling that story in some other way. And you know, that's fine. With baseball, one of the challenges was there, you know, so much, there's more to now but there wasn't a lot of serious academic historical scholarship on the topic. Frankly, there were, you know, history of the Boston Red Sox, or biography of Babe Ruth, or you know, something about baseball, and the Black Sox scandal, but there wasn't really a big shelf of serious kind of academic historical work. So we really had to find historians who knew American history and happened to be baseball fans, and they could help us kind of get this in the context, because we weren't just doing a sports show, we really wanted it to be about the story of America through the lens of baseball,

Alex Ferrari 11:34

right in the watch national national parks one was, because I'm a huge national parks fan. And that's actually kind of my dream project as well, because you guys got to travel to every single

Lynn Novick 11:44

measure the water, I did work on that, but I, I know, an invitation to go to all those incredible places may have it

Alex Ferrari 11:51

must have been a rough job, like okay, we're gonna go to Yellowstone again, oh, we gotta, we gotta go to Yosemite again, you know, but those, that's another thing that you guys get to do. And sometimes, obviously, depending on the on the, on the topic, but you get to meet some of the most interesting human beings who've ever lived, you know, and, and you're talking to people who either know a lot about a subject or are part of the subject, like you said, a jet and jazz with Marcellus. He, he is like a living legend. So to talk to someone like that. I mean, that must be amazing as a documentarian to be able to talk to you talking to history, essentially,

Lynn Novick 12:28

yeah, that's one of the best parts of my job, I would say is the chance to meet and get to know people, really spend time with them and hear their stories. And, you know, you inevitably understand the history in a completely different way, once you've talked to someone who lived through it. So, I mean, I will never forget, we're working on a film on the Second World War. And some of the people we meet don't end up in the film for whatever variety of reasons. So we were trying to find some people who had been on D day and Omaha Beach, and I remember going to visit the veteran and his daughter had contacted us, and this happened a lot on that project where a family members would say you should talk to my dad or my uncle. So we would go to their home. And I remember going into this man's kitchen, and his daughter said, Dad, Dad, you know, Linda's here that they're making the document tree, they want to hear about your time in the war. And he was saying, okay, okay. And I said, so, you know, after chitchat, whatever, just not talking about the weather, then I sort of got to my point. So I understand you were on D day. And he said, Yes, I was in the engineers Battalion, which means I had to get out early to kind of take out the mines and blow up things that shouldn't be there and credibly dangerous job. Okay. So he said, so I'm sort of trying to understand what he's saying. And he said, I got out of the boat. And for me, D day, I always think, how do you get out of the boat? I mean, I would not be able to get out of the boat. But everyone's getting out. So you get out, even though you're getting fired on. He said, I got onto the beach, a shell came in and killed my best friend. And then he started to cry. And then he didn't talk anymore. So he he and he had to leave. I mean, he couldn't actually speak. understandable, right. And his daughter sort of said he never talks about this. And she had hoped that he would be able to but he actually was so traumatized. Even 60 years later, he couldn't speak about it. And even though we didn't put him in our film, because he he couldn't really participate in that way. Spending that morning with him helped me appreciate in a very visceral way. What we're asking people to do by reliving these really difficult moments and how hard that can be. And the gratitude and humility you have to have because you just, you know, the generosity of someone to even try to do that is is is sort of inspiring.

Alex Ferrari 14:48

Yeah. I mean, it's one thing to talk about jazz and talk about my good times playing baseball. Right another thing about like the Vietnam War, you did the Great War, World War Two and all these other like dark dark times in American history. That's what I love. What you can do is you really are historians of the American experiment. You know that you all I mean, is there any, it's all American based pretty much if I'm not mistaken, right? Is there anything world based? I don't?

Lynn Novick 15:20

Well, the Vietnam War is the first time for that in work that Ken and I have done together where we really tried to represent a story that was, you know, as Americans were interested in it, but the Vietnamese story wasn't as important to us, right. So we tried very hard and I, I made a number of trips to Vietnam with Sara Botstein, the producer, to get to know Vietnamese, people who had lived through the war and to hear their stories, and hear how they talk about it and what it means to them, which is very different than how we talked about it and what it means to us. So, yeah, so that's the first time we've really ventured to another country, another culture to that to gray so that the film hopefully really represented, you know, as best we could do, not just an American story,

Alex Ferrari 16:07

right? Exactly. Yeah. It wasn't a completely American point of view is like the oppressor and the pressy. kind of vibe, or that's not the proper word, but the

Lynn Novick 16:17

four antagonists or whatever, yeah, yeah, yeah, antagonists attack Exactly.

Alex Ferrari 16:21

So you got the point of view, because to us, to them, we're the bad guys to us. They were the bad guys. Like I always tell people, we're all everybody is the hero of their own story. Nobody goes to sleep twiddling their mustache going. Evil. No, everyone thinks that they're the good guy. If they're right,

Lynn Novick 16:40

which is, and you're right. And for Americans, the Vietnam War was the first time and if we really had to face as a culture, maybe we're not the good guys. Maybe we're not always good guys. And that was a reckoning, that we still haven't really sorted out.

Alex Ferrari 16:54

Because after World War Two, we're just like, you know, as you were, we're g we're super we're Superman. We're, you know, American Pie and baseball. And we saved the world. And that and we're still kind of on that high. In you know, that pr, pr is still running. But I think from the Desert Storm and all these other wars that we've gone into people's like, you know, maybe, maybe we're not always the best guys. We try. We try.

Lynn Novick 17:22

But like any human try,

Alex Ferrari 17:24

but the thing is, like any human being, we have different, you know, we can't be perfect.

Lynn Novick 17:30

Well, we're certainly not perfect. Yeah. I think if we're perfect, it would be so boring. It's exactly sitting here talking because there would be nothing to tell. So I think it's especially hard for Americans, though, to really examine our flaws and our failures. I do think culturally, like you said, We'd like to think of ourselves as the good guys, and that we're always on the right side of history, and that we, you know, stand for something that's good, and, you know, inspiring and noble. And it's a lot more complicated

Alex Ferrari 18:01

as a human being is like, you can't it like there's so many layers, like as they say, Shrek, like Shrek, you're like an onion, multiple layers, multiple layers. Now, the other thing I find fascinating about documentarian work is and I've worked on documentaries and post editing them, but nothing like a 90 minute, you know, documentary. So I have some very small experience doing that. But the durance that you need to have as a filmmaker, to sit like some of these projects not only takes years, I mean, some are like, Did you do anything to quit like a decade? Or am I exaggerating? Well,

Lynn Novick 18:41

the national parks, I think they really did work on for almost a decade. And that allowed them to visit all those parks and film them at different seasons and accumulate all that material. But but in fairness, it's not the only thing that they were working on. Right. So it's not your only project for 10 years. But you know, we might work on it a part of the time and work on something else that shorter term, and then come back to it depending on

Alex Ferrari 19:04

Yes, yeah. Cuz I'm assuming you guys don't just sit down and just do like, okay, we're just doing jazz for the next three years. You've got four or 568, different little, some like Hemingway over here and, and a jazz over here in the Vietnam War over here, Frank Lloyd Wright over here, and you're kind of like dabbling in a bunch. It kind of keeps you all busy and sane.

Lynn Novick 19:24

Yeah, well, I mean, Ken does work on I think he says he's working on eight or nine projects right now. Right. And they're all at different stages of production. So he can be in a room with one project. And, you know, the film is being let's say, they're shooting interviews for another project and developing a script for another project. So using different parts of his brain for different aspects of that, for me, I like to work on maybe no more than two or three projects at a time. So my brain can't handle it. So but that's enough. So, you know, today I'm working on one or two projects and tomorrow, but like eight or 10 I don't know how can does it honestly, it's amazing.

Alex Ferrari 19:57

It's exact, but even two or three is like you know, because as As narrative filmmakers, you generally are working on one. And that one could take two years. You might be writing maybe something else, but I've been on projects that's take two years, three years. And that's all you do all the time, it becomes kind of crazy, but the endurance is remarkable. Now I have to ask you, what do you think the job of a documentarian is, in your opinion?

Lynn Novick 20:23

Wow, you know, documentary and the time I've been working in this field, which is more than 30 years, it's really evolved. And, and even the genre such as it is, is so capacious, there's so many different kinds of documentaries and different approaches and different kind of philosophies. So, you know, it's almost hard to pin it down, because different people approach it with different expectations. So I like to think that it's a way of putting on the screen, it doesn't have to be the big screen, it could be a small stream, a true story, not based on a true story, or inspired by a true story, but an actually true story, something that really happened with real people. And that, then, you know, that's the number one for me, then is it going to be sort of a story of something that's happening right now, that would be sort of a, you know, present day story that you're following action as it happens? Or is it something that happened in the past, like what we have mostly done or though not exclusively, where you're excavating? A long ago story and trying to put the pieces together, like you were the jigsaw puzzle, of, you know, figuring out what happened. Hopefully, it has a beginning, middle, and end Aristotelian poetics of just, you know, a story that kind of makes sense, and the way that we think of narrative, which means you have to impose some kind of order. And some kind of, you know, right, you have to pick out the things that you think fit to get your beginning, middle, and end, you can have some detours along the way. But ultimately, for me, it's has to touch people, it has to have a human dimension and mean something to the people who watch it so that they are engaged in care about the story that people the information that is true, you know, and that you come away with some new perspective, or deeper understanding of some aspect of history, the human condition, what it means to be alive, you know, those kind of things,

Alex Ferrari 22:21

the because, you know, a human story, you know, history generally is not so neat, as have a middle, it's not constructed in the middle, a beginning, middle and end a human life. I mean, yes, does have a beginning, middle and end, but it could be very anti climatic, it could be very wide open, it could be multiple different things. So it's interesting how you, you are able to put together you have to put a structure, there has to be some sort of narrative story put into history, which is so much more complicated I feel than just writing what I know, I've seen in some of your other interviews that you're like, Oh, you just said it here. It's like, I can't do afresh come up with the story. I'm not that creative. But I'm gonna give you more credit than you're giving yourself is to construct a narrative out of history. Yes, sometimes it falls. But sometimes you just kind of really work it and understand the structure of story. So well, even more so than I think when you're creating it.

Lynn Novick 23:17

That may be I've never tried the scripting adventure. So that seems like it would be harder and easier for me that, you know, I came to understand this in a deeper way, when I was working on documentaries that I made over a number of years called college behind bars where we were filming not history, but life as it was happening. And it was filmed over four years, as we got to know people, Sarah Botstein, a producer, and I got to know people who were in prison who were enrolled in college, which is very unusual, because most people in prison don't have access to college of any kind. And they were in this incredibly rigorous and impressive program called the Bard prison initiative in upstate New York. So you know, we would come in and out of the facility multiple times a year with our cameras, sometimes without our cameras, other times, get to know people, or hopefully earn their trust over time, and follow them around through classes, into the yard into their selves, you know, meet their families, and kind of understand the beginning, middle and end was basically you're enrolling in the program. And hopefully, four years from now there'll be graduation. So luckily, school does have a beginning, middle and end, right. So we knew, we hope we begin with, you know, orientation and end with graduation. But along the way, we had 400 hours of material of all kinds of things, you know, that we didn't know how they would fit into our film or not, and you just be kept filming. And a lot of the times we wanted to call the company seat of the pants productions, because we just had I felt we had no idea what we were doing. But if we sort of showed up enough, maybe it would all make sense later. And working with our editor, Fisher Reedy and assistant editor chase Horton meet eventually managed to kind of wrestle these 400 hours into four one hours where you really get To know people and see how they evolve, and are transformed by the process of education, and overtime, get to know why they're in prison and their families. And some of them came out of prison while we were filming. But at the beginning, we had no idea. And we really did have to impose a structure on each scene. And each episode, and on the whole thing,

Alex Ferrari 25:20

there wasn't any structure. Right? And that's the thing that I feel that with, with the historical documentaries that you do you do those? They're safer in a sense, because, you know, you're discovering the archival, yes, you'll have surprises. And yes, you'll have things but it's not gonna hit you not gonna blindside you. Whereas if you're following real life, it's unfolding in front of you are on the edge, you really have no idea and you might start the documentary and the story in one way. And then all of a sudden, it just turns like, that wonderful document or Hoop Dreams back in the day. Oh, my God, like, how did that like, you know, just the like, Oh, my God like it. So something like that you really it's a completely different kind of documentary and different kind of filmmaker to go down that. How did that feel jumping from? From very safe, historical, very long, laborious, you know, process to? I'm on the edge? Like, you're like, Yeah, what's happening? How did that?

Lynn Novick 26:21

I mean, it's kind of exhilarating and terrifying, and exhilarating, in a sense of is exciting, because you don't know what's gonna happen. Right? And you sort of are open to whatever happens, we'll figure it out. But it's also certainly scary to think, wow, what if I mean, I had the feeling okay, we started this film. But what if the Department of Corrections which gave us incredible access, or the students, the people in the film decided they didn't want to do it anymore? Right, that could have happened, someone could have said, you know, what, actually, we're not doing this anymore, for whatever reason, that could have happened or, and things did happen. People got in trouble and was transferred to another facility and couldn't be in the program anymore, or something happened in their personal life or, you know, academic things, whatever. Just all kinds of things happen that you can't predict in life. But when you're trying to make a film, it can be very destabilizing. You just have to stay open to that. But you know, even with historical films, I mean, for the Vietnam War, it may seem like it made all sense when you see the final film, but at the beginning, we're not at all sure what the hell we're doing. Yeah. Because, first of all, I've never been to Vietnam, I don't speak Vietnamese, we have to go and want to go over there and meet people and figure out how to what questions to ask them, and who to talk to, and how we're going to do that. And we've never really thought about the Vietnam War, from the perspective of the Vietnamese get turns out, it's really complicated. So even just, and we wanted it to be from the ground up ordinary people telling their stories, but then we have to figure out well, we're not going to interview john mccain and john kerry and Henry Kissinger, we're going to talk to regular people with regular people. So it was you know, word of mouth and sort of going out into the world and trying to find people who fit certain criteria that we had of being in the anti war movement or being on a college campus or being you know, a soldier who then turned against the war, we had like different ideas of things, or someone who covered the war. But we didn't really know what that would be. It all makes if we do our job right at the end. It looks like it all fits in and makes sense. But it really doesn't at the beginning. And even at the middle of we're not too sure.

Alex Ferrari 28:31

Now with college behind bars, I wanted to wanted you to kind of express to the audience what it felt like because I was I was I had the privilege of doing location scouts for a film that I was going to direct and every prison in Florida, I went to every prison that would allow us to I was to shoot there if we wanted to shoot it. I got access to it. And I'd never been in, you know, in prison. I you know, I was a boy from Florida like, I mean, I I'm a good boy, I don't have never been in prison. So when you walk through those gates, and you feel the energy, and we were in empty areas, we weren't within you anywhere there was inmates, though, we did see like some of them were very low, low security, low security areas, so that you see them walking and stuff. But I never was in a place where there was like, you know, as as they said, the HBO show oz or something like that. I wasn't in that. But that feeling of that place, the energy the almost the ghosts, if you will, of that place. Did you feel that? And you were going into a place with live, you know, people and interacting with people. Can you express to people about how that goes and how you put that onto the screen with college behind bars?

Lynn Novick 29:48

Yeah, thank you for asking. You know, I do think it's important for all of us as citizens to try to have some proximity to the problem of criminal justice and incarceration. In our society, which is horrendous and appalling, and it's, it's not easy to get access, if you're not don't have a family member that's caught up in this, you know, it's far away from most of us, and it's behind walls. And so I had never had the experience of being inside of prison until I got invited with Sarah to give a lecture basically, in this college program, and that we went into that we went through the, you know, the double gate, and then the other double gate and then walking through the, you know, long hallway and kind of could see the yard over there, and then down another hallway and then update, you know, I remember every step of this way into past an officer into a classroom. You know, it's, it's an oppressive, dehumanizing, really just degrading and oppressive environment. And it's meant to be that way, nothing, there's by accident, it's all by design. It's very purposeful, and especially, probably do in Florida. But in New York State, the majority of prisoners are black and brown, the majority of the officers are white, the dynamics of how control is managed and security is done is I found extremely disturbing. Just, I did feel, you know, it's just I found it really, really upsetting and disturbing, to say the least. And yet. I also think it's easy for us if we have seen Oz, or locked up, or the other kind of Hollywood versions of incarceration, to have a very skewed perception of what is actually like, and one of the most profound things that one of the students that we've gotten to know really well said, is that suicide is a much bigger problem than homicide inside prisons. It's about despair, and loneliness, and isolation, and giving up hope, and a place where there is no hope. And people, you know, to compensate in different ways in that environment. And so we have this image of this violence and you know, awful things happening, but actually, it's most, a lot of it is really designed to make people isolated and lonely. And to not care.

Alex Ferrari 32:11

Yeah, I'll tell you the one of the officers, that was our tour guide, he actually is like, do you want to go on one of the cells and I went into one of the cells and they shut the door behind me. And that's sound, I'll never forget the sound, I'll never forget the sound because I'm like, I'm playing, I'm cosplaying this right. Now. This is right. This is not real for me. But I can, I can feel it. It is a feeling and you were like, it was visceral. And I was a young man, I was in my mid 20s at that time. And boy, was it powerful. And I agree with you. I think if any of you ever, everybody could just feel that. I think our opinions of that whole system, honestly, needs to be needs to be addressed in a very, very, very big way.

Lynn Novick 32:55

I agree. Well, that office experience that we had, you know, we did, we spent a fair amount of time inside people's house with them. And when you see the film, people who are the people that we got to know are college students, so their cells are full of books. So you're seeing American literature, art, history, philosophy, economics, algebra, Mandarin, you know, all the things they're studying, they're their selves are full of books, and they're doing serious academic work, while in this very inhumane space. So there's kind of like a cognitive dissonance about that. But also, it's extraordinarily inspiring to see that even in this dark place. They hold on to and many of them have talked about this just a sense of hope that there's something other than this place. And the way to move through it is to make sure you use your time the best you can and to, you know, open your mind in whatever way you can.

Alex Ferrari 33:47

Yeah, I would, I would, I would completely lose myself in in books, I would completely lose myself into that I would escape into that, because that just makes the most the most sense. The most sense without question. Now you were talking about 400 hours for this project? 400 hours, cut down to four hours? Uh huh. I mean, I've edited 25 years. So I understand the process. I've never had 400 hours of footage. So how do you be? I mean, I'm assuming it's a team. There's not one person?

Lynn Novick 34:23

Well, you know, in all honesty, because we're shooting digitally these days of cameras rolling, especially if we're in a prison where you just, you know, yeah, just keep rolling, because you never know. So there's a lot of that 400 hours, probably 50 hours, you don't even ever look at that just as just like, you're walking down the hall or whatever, and you're not really you know, but nonetheless, we filmed interviews, so we transcribe them only pick out the best, you know, moments from those. We filmed a lot of classes because it's a film about college. So in those an hour long class might be five minutes. That's really interesting. So we sort of like whittled down from the beginning, that what we'd say the highlights, and then we basically put them in a String out and watch it and our string out was like nine hours long. So then it was just that's not bad, though. 400 to nine, you know?

Alex Ferrari 35:08

Yeah. Right. And in the scope of the projects, you do nine hours, bad.

Lynn Novick 35:12

Yeah, well, we were planning to make a feature length Doc, though, at the beginning, we had nine hours to boil down to 90 minutes. And I realized that's not going to be possible and make what would be possible, of course, but we just decided to go back to PBS and saying, you know, what, this material is so rich, and they actually had said at the beginning, you know, you might end up with something bigger than the feature because this is a very profound and, you know, rich story to tell, and to get to know people and see what happens to them. So you know, we, it, I have, our editors do an enormous amount of the time spent looking at the material over and over and getting to know it really, really well, and picking out the things they think work best. And then we would react to that and kind of fine tune and home with them. And we also brought in the people who were in the film, if they had been released from prison, especially to see it and kind of help us to get back to my point about being authentic authenticity and being true. You know, they live this and we've got a version of it, that we captured with our cameras, right? But we didn't want to put something out that didn't feel authentic and true to them. Because you know, you have the camera on for a little while you turn it off, or you look over here, but something else happened that you didn't notice. And just there's a lot of subtleties to what gets into, you know, gets captured on film or whatever we capture things on nowadays. It's always

Alex Ferrari 36:39

it's it's hard because I need to Xerox like, it's just film film is gonna be film, I need to film it or I need to tape it. You know? It's just the way it is. I just heard I heard a newscaster the other day say like, Oh, yeah, we were taping this. I'm like, they were on it was on an iPhone. It was on an iPhone, come on. But it's just it's just it's part of the lexicon. Now, tell me about your new project Hemingway, which is a fascinating subject. He is such a larger than life figure in American history. In the literary world, he is a giant up there with Mark Twain and Shakespeare. I mean, he is our Shakespeare in many ways, a give or take. But he is a giant and has so much information or like, even I, I've read a bunch of Hemingway, you know, growing up and right, but and but the myth of who Hemingway is, is larger than life. It's as art like I don't know much about Stephen King's personal life, though he is a giant in the literary world as well. Different than Hemingway. But, you know, other than a few things he's not there's not a myth about him. No, there is a myth about Hemingway, how did you go to tackle this subject matter?

Lynn Novick 37:56

Yeah, well, you you you really hit the nail on the head there because Hemingway is unusual in the sense that he, the myth is sometimes bigger than him. And I think many people that we talked to said it kind of gets in the way of actually seeing him. But he's so famous because of this myth. His work is extraordinary, as he said, but it's the myth that people know. And he created that that didn't just happen to him. He was the reason why there's a myth. He very consciously created this persona, and then kind of fed the flames of that throughout his life in very conscious and sort of

purposeful ways. Was he branding? Yes, exactly.

Alex Ferrari 38:39

He was branding himself. He was he was, he was an influencer before they were influencers.

Lynn Novick 38:44

Exactly. He understood all of that in a way that I think a lot of writers don't, or wouldn't want to more than like a movie star, or a rock star, you know, he had a sense of his brand. From a young age. It's fascinating, really. And that's a story in and of itself.

Alex Ferrari 38:59

Before there was ever a concept of a brand, like a human being being a brand. Like, you know, Marilyn Monroe became a brand but Maryland did not know about it when you know, those big movie stars of the day did not think about that. But you're right, we're using rock star movie star, he essentially is the rock star or movie star of the literary world.

Lynn Novick 39:19

Yeah, I agree. And that's not necessarily the best thing for a writer, just to say, you know, he's not playing arenas, you know, anything like it on the big screen, right? So he's writing in his room on his typewriter. So but what he was famous for was kind of these escapades, you know, hunting and fishing and you have, there's, I can't tell you how many pictures that are of him posed with the enormous fish he caught or the animal that he shot, you know, or in kind of like pretending to be boxing, you know, all these really macho sort of what we would now call hyper masculine poses. And even in his own lifetime, it got a little tired, and there was criticism of it. You know, Even then he was he was at the extreme of this masculine persona. And he also kind of knew that, but I think he was trapped by it at a certain point. And it's true. He did enjoy the things that he was famous for doing. But having to perform the role of being Hemingway must have been sauce very tiring. Yeah, exhausting. Exactly.

Alex Ferrari 40:23

Yeah, cuz once you build a myth like that, you've got to live up to it.

Lynn Novick 40:27

Right? And it's

Alex Ferrari 40:28

a beast that you can't control. And that's the thing about brands and about your career, your legend or your myth that you create. It goes off and you can't, if you build to a point, it becomes its own monster. And I think I think the myth is the monster that ate Hemingway. Unfortunately, unfortunately, at the end, it was too much for him. Yeah,

Lynn Novick 40:50

I mean, it is it's a tragic story back to our hero's journey from Joseph Campbell there, you know, it's, there's hubris, and there's just tragedy that happens to him and some things he's responsible for, and some things he isn't. There's a family history of mental illness. And so, you know, you're born with that that's a something you can't control and the time when he was alive, certainly true now, but even more so then there's such stigma around mental illness, depression, anxiety, no one talked about that. They would say, somebody went for a rescue here, or they're just taking a break or something, you know, you would rather I don't know. I mean, the shame of going to a mental hospital. You know, he didn't want that. And he was suffering from very serious psychotic depression, among other things at the time that he should have gone to a mental hospital.

Alex Ferrari 41:41

Did he write any of his works? While really going through some episodes?

Lynn Novick 41:50

Yes, I I'm, I'm not sure I can line up everything chronologically. Exactly. But he also suffered from alcoholism, chronic alcoholism, which no one does affect your power to

Alex Ferrari 42:06

mission, mythical alcoholism. I mean, yes,

Lynn Novick 42:09

he glorified drinking, right. So but then he, you know it that got the better of him. And then also, he suffered from a number of serious concussions, head injuries, over the course of his life, probably eight or nine very serious concussions, which now we know that does really serious damage to your brain and your capacity to think and function and your moods and can cause depression and paranoia and all the horrible things we've seen happening with people who have suffered from traumatic brain injury and CTE. He had no idea about that. So he, you know, one of the psychiatrists who studied his trajectory suggests that he had a kind of a dementia, which is not like you don't know your name, but you there's a kind of confusion and lack of capacity to really do organize thinking. And he really struggled with writing. The last 10 years of his life, he had a lot of projects, he couldn't finish any of them. He couldn't figure out how to edit himself. He was just sort of overwhelmed with a lot of ideas, but nothing really jelling. And he did manage to write the old man to see in the middle of all of that, by some miracle, they had a few months of clarity. But before and after that he was really a mess.

Alex Ferrari 43:24

It's it's fascinating. What was the one thing that you discovered by Hemingway that you did not know when you started this project? that surprised you?

Lynn Novick 43:36

Well, I mean, a lot of things surprised me because I was not an expert when we started the project. So it's hard to say the one thing but one of the more fascinating themes that emerged in the course of making the film was an eye maybe I kind of vaguely had heard this, but I don't think I really understood it, that he for this hyper masculine guy, who played the part of the man who was the man's man, right, who was always strong and tough and didn't betray weakness, and, you know, courageous and morally right, and all these things that he, you know, held such high esteem. He was vulnerable. He was anxious, he was empathetic, he was concerned about how male behavior affected women. So he writes about that really beautifully in ways that I don't, I didn't fully understand. And that, you know, we have this phrase now toxic masculinity, which I didn't have that in my vocabulary 10 years ago, but I understand what it is now. Hemingway could be the embodiment of that in his personal life, in his relationships with his wives and other women in his life, but in his work at times, and not always, he critiques that, so he writes a story called hills like white elephants, where it's a man and woman at a train station. This is written in the 1920s. So it was quite, you know, I don't know, risky thing for him to do. But it was unusual in that it was about an abortion. man wants a woman to have an abortion. Now, she doesn't want to, they never say the word abortion, he just keeps saying to her, it's just a simple operation. They just let the air in, and then you'll be fine. We'll be just like we were before. I promise. It's just a little operation. And she's not sure. And he keeps at her and at her at her. And when you read the story, you're not thinking, Well, what a great, strong, tough guy this is, you're thinking this guy's a jerk. I don't care if you're a man or woman reading that story, your sympathy, and you're the hero where the moral center of the story is the woman. At one point, she just says, Tim, will you please, please, please, please, please, please stop talking. And, you know, the Hemingway the myth of Hemingway should be capable of right having the sensitivity to write that story in the way

Alex Ferrari 45:58

that he does. And that's that's the beautiful duality with Hemingway is that he portrays this complete macho man drink until you're you fall over, then get up and smoke a cigar and write a masterpiece, you know, while while you're in the keys are in Cuba, and then you're hanging out with Fidel and all this, like all of that, that's the myth. But if once I did, I've seen parts of not all of them, because again, it's six hours, and I have children. But the parts that I have seen that he when he was younger, was dressed as a girl, and his sister was dressed as a boy. And above that, through the through his life, he actually had his wives cut their hair short. And they would this gender kind of thing that they he would like he would play with. there's a there's a sensitivity behind all of all of that macho pneus. And I found that to be true with. I've mean, I've spoken to many, many people in my life. And I've met many, many interesting human beings in the entertainment industry, the more macho, big they are, generally, the more insecure, the more scared, the more they lash out, because they they want to show any, and they can't show any weakness, because of something that happened in their childhood or something like that. It seems very similar to with Hemingway, he put this, this shield up, I think it was almost a protective thing for him, because he didn't want anybody to know who he really was. But it would slip through in his writing, he couldn't hold it back there. So that's really, he's such an interesting character.

Lynn Novick 47:34

I agree completely. And you know, that, that what you just described is something I was sort of focused on, we started the project on this kind of obnoxious mess, and some beautiful writing that I loved. And I didn't understand the complexities of what you just described, until I've gone all the way through the whole life. And, you know, late in his life, he he started to write more explicitly about his interest in gender fluidity and in gender role playing and in a kind of vulnerability in his intimate life. He never published that during his lifetime, but his family has allowed some of this material to be published, especially in the novel called the Garden of Eden, which is not my favorite in terms of Hemingway, great work. But in terms of understanding Hemingway, the man, it's really fascinating. You see a man, his wife is sort of transitioning to male, I would say in the story, and they bring in another woman into the relationship. So there's a polyamory component to this, the husband becomes kind of the female in bed with her, the wife who's more of the becoming more of the husband, and then this other woman, and it's very interesting and relatable to us today, in a way that in his lifetime, I think, you know, what, if he couldn't publish it, let's put it that way.

Alex Ferrari 48:48

Right. I mean, it be interesting to see how, because and there's that whole concept now kancil culture, and you know, like, you know, oh, you can't say that you can't do this. You can't do that. There's a lot of stuff in Hemingway, that is arguably like, when's that? When's that shoe gonna drop? And he second now, when is it? When is someone going to go? Well, we can't we got to pull out these books that I mean, Hemingway's, which, what do you think? I don't want to talk about canceled culture in general, but specifically with Hemingway? Why do you think that he kind of transcends that? Because there's nothing like if they're, if they're knocking out, you know, the Swedish chef, and, and Dr. Seuss, I mean, anyways, a much easier target than Dr. Seuss. So what do you Yeah, makes his work kind of almost impenetrable to that kind of, you know, what makes him stand away from that?

Lynn Novick 49:43

Yeah, you know, we'll see how it all plays out.

Alex Ferrari 49:46

We're still early.

Lynn Novick 49:49

And I'm glad we're having a conversation as a society about you know, reevaluating these icons of the past and looking at them honestly for who they really were and what they really said. And what They say about us good and bad. And I think that's healthy. And I'm not big on the Pantheon, where you can only have so many people up on Mount Rushmore, or you know, it can only be four writers and you have to pick, I think we have room for a lot of people to be read and discussed and to whose voices matter. And it certainly shouldn't just be Hemingway by any means. But taking him out of the equation is a mistake, too, because he helps us understand some of the problems and challenges in his limitations, as well as his strengths, raises incredibly offensive words, hurtful words, he, there's anti semitism in his work that I personally find deeply offensive. But it doesn't mean that I don't want to read this on all survivors, it means that when I do read this, I'm also rises, I'm going to be thinking about anti semitism in our culture, and why does it exist? Does it still exist? Why would you know, what does it say about the people who read this book then? and loved it? You know, it's in other words, it's part of our history that we have to face, like it or not. And there's also potentially a critique of those things in there, too, if you want to look at it that way.

Alex Ferrari 51:10

I mean, look, you know, look at Mark Twain. I mean, you look you read Huck Finn. I mean, he's saying some stuff. That's probably not the most PC stuff in the world nowadays to listen, but I always find it, especially in history, and you're much more more of a historian than I am. But from my, my, my limited perspective is in history. It is a product of its time, and has to be looked through those that lens. If it's being brought into today's world, there's a conversation to go, you know, what, what they said, there isn't appropriate from our point of view, they're just like, and I promise you and everyone listening in 100 years, they're going to be looking at stuff that we're doing and going Yeah, well, we really the social media thing, not really the best idea, you know, you know, polluting the entire planet and killing ourselves. So not denying the global warming, not the smartest thing. So we're going to be judged as well. So

Lynn Novick 52:04

I think we should be and we should be right. Yeah, look, I mean, just because you brought him up Shakespeare, there's racism, there's anti semitism, there's misogyny, you know, and we don't just say, well, we're not going to read Shakespeare or we aren't going to ignore those things. We're going to have that conversation. You know,

Alex Ferrari 52:21

it's as a teaching tool, I feel it's a teaching more than anything. With my daughter's with my daughters, as I'm watching things sometimes now, you know, things that I grew up mechanical things I grew up with. I mean, I'm stuffed suffice on TV, some episodes of Tom and Jerry, some Looney Tunes episodes, which are straight up just racist, completely racist. And we didn't think twice about it. And then my daughters will watch something. And they'll point out what is that? And then there's a conversation to be had about it. It's a teaching tool at this point in the game, but you can't sanitize it. Because,

Lynn Novick 52:57

right when,

Alex Ferrari 52:58

let's say a child is sanitized from all of that. And when they hit that, imagine getting hit with racism for the first time at 30. Yeah, you can't. It's a difficult, like the concept of racism, like you've

Lynn Novick 53:10

been so sheltered. Now. It's out there, right?

Alex Ferrari 53:13

You shouldn't really

Lynn Novick 53:14

Yeah, I do think with children's literature and children's books and children's media, it's maybe a little bit different criteria, right. And for adults, because we have the tools hopefully to kind of have that critique in conversation. We're working on a film, Ken and Sarah Botstein and I about America's response to the Holocaust. Right? So we're, and we're trying to understand anti semitism as a factor of life in Germany, and we came across a book that the Nazis put out a picture book, about the horrible Jews and how they are, you know, subhuman. And, you know, we'll destroy you and put you in the beautiful illustrations, incredible, you know, with a devil. And I mean, if you were a kid reading that you would just, it's captivating. So I kind of think, well, maybe for children's literature, we have to have different criteria, because children don't have the framework

Alex Ferrari 54:06

or the tools

Lynn Novick 54:07

to read that. Right. Exactly. So I understand the impulse to remove some Dr. Seuss books, because, and that was done by the estate, when they decided they didn't want these books out there anymore. You know, the cat in the hat is still great.

Alex Ferrari 54:21

Look at the cat hat is still great. Yeah. And it's, it's, it's, we're living in very interesting times, and I'm as a documentarian, I'm assuming you're looking around going, Jesus, I'm just pulled there's so much I want to say right now, there's so many different projects I want to do. But out of all the projects you've done, which is the most difficult which is the one that was the longest, just even if it wasn't timewise just difficult to get through because you've tackled some tough subject matter.

Lynn Novick 54:48

I you know, I think, truly the Vietnam War series and the college behind bars which we were working on, more or less at the same time, both were dealing with enormous trauma traumatic extreme. variances and tragedy. And cause behind bars was also an uplifting story of transformation. But there's tragedy and devastating human experience within it. So and the Vietnam War is just an unending tragedy. So spending the time to get to know people who are still carrying that loss and grief, unprocessed, and anger and rage and disillusionment, especially with our country. As we said before, sort of, you know, we weren't always the good guys, and our leaders lied to us and let us down and told us we were there for one reason, or other reasons, or the reasons kept changing, or said, we were winning when we weren't or minimize casualties on all sides, just the kind of the betrayal, I would say, of the American government, of the people by the government, and the Vietnamese government. Not a whole lot better, by the way. So you just have epic tragedy on all sides, kind of sitting with that, for all those years was

Alex Ferrari 56:02

difficult to to me day in, day out. I've been emotionally spiritually it must been rough.

Lynn Novick 56:09

Yeah. and spending time with the people who were still carrying that weight. And then, you know, watching the film, as it evolved with some of the veterans that we got to know and some of the people who protested the war and still felt very raw about it. It was it was really painful, I think. So that that experience that sits with me, and there are some days both on both of those projects of, especially filming interviews with people who shared extremely difficult stories and really open themselves up in ways that I have never experienced before. was just a profound experience that I will never forget.

Alex Ferrari 56:51

Now, I have to ask you, I because I'm not I just need to know your opinion. What do you feel about the rise of the docu series? Oh, of Tiger, King of those kind of, you know, that's why I want I know you cringe right there for people that watching she cringed. I want to know what a true documentarian who's, you know, considered a very serious award winning someone who's deadly serious about what you do. For debt. You know, for decades now, there is a rise of docu series, and some are really good. Some are, you know, Tiger King is just what it is. I'm not specifically asking you to comment on specific ones unless you'd like to, but just in general, the whole rise of docu series, because there are some docu series that are fascinating to watch.

Lynn Novick 57:38

Absolutely, absolutely.

Alex Ferrari 57:40

We just, which is the one that we just want. My wife was watching the one on the Menendez brothers, and now that there's a whole movement to free them Menendez brothers, and I'm like, are you like, there's a bunch of millennials? Oh, like freedom. They were like, What is going on? And watch that whole series? My wife and I were just like, are we free Brittany? Like that, you know, that whole thing? That was a fascinating document. She's just sitting there going again, and please. Well, you can do

Lynn Novick 58:07

it. I'm just curious, oh, wait into this. I don't I you know, I look. Sometimes I feel there's a very fine line between telling someone's story and exploiting them and sensationalizing them and actually using them. And, you know, and sort of having the it's really a reality TV kind of ethos in the documentary, space clothing or whatever, right? And so the people are kind of performing, you know, outsize version of themselves like Hemingway did. Right. But you know, they're not there. They're, yeah, they're on camera. So but, you know, how much are they able to really have agency and that maybe a lot? You know, there's it's just it gets very complicated, I think in terms of what is a documentary and what is kind of a performance. Now, everybody, when there's a camera on them, including me, right now, we all perform to some degree, we're, you know, if I were just talking to you on the street, it would be a different conversation. We all know that. But if you are being filmed, and you're sort of the more you act outrageous, and the more you just play it up, the more you're going to be on screen, then you know, that's what happens. So everybody gets it, and everyone is part of that. So some So anyway, I think some of the some of it is in that mode, right? And Tiger King I would say I didn't watch the whole thing I heard it was great. It was beginning of the pandemic entertaining, entertaining as heck back great. It totally entertaining. But after a while, I just thought, where's this all going? I don't know if I really care in the end. So

Alex Ferrari 59:47

it was it was it was a I think the timing of that release. It was the beginning of the pandemic. That's why I was at home. And everybody was like, What is this? I saw it come across my screen. I was like, what I saw my wife I was like, why are you watching this? And I'm like, because I it's the pandemic and there's nothing I gotta watch this. And it was a UK it was it was but it was a train wreck. It was a train wreck and you were watching the train wreck and that is very reality show style stuff. Whereas in you know Oscar winning documentaries like searching for sugar man, or, or the wire? Is it the wire or the Yeah, the

Lynn Novick 1:00:22

wire is actually not a documentary. A great TV. No,

Alex Ferrari 1:00:26

no, the one about the guy who, who won the Oscar. Yeah, man, a man or a white man on what? You watch those kinds of stories and you're just like, Oh, my God, that's like amazing storytelling.

Lynn Novick 1:00:38

I, you know, I look, I mean, I think a docu series is wonderful, because it's like reading a novel or having an extended podcast where you really dive in and get to know people and a story from multiple perspectives and over time. So if you listen to cereal for eight hours, you get really sucked into Who are these people. And there's different ways to think about this. And, you know, if it's artfully done, it's totally captivating. And I'm really thrilled that these that there's a huge audience for this kind of storytelling and these kind of stories to be told. I just when it gets into the sort of sensational, almost exploitation, exploitative realm. I get uncomfortable. So like making a murderer, right. That was fascinating. Right? You know, that was landmark docu series. I'm not sure in the end, that they fully gave you all the information you needed. They sort of shielded certain parts of the story from the audience. I think that is problematic. I loved oj Made in America. I thought that was one of the greatest amazing share brilliance. Yeah, absolutely.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:43

But there's, but I think at the end, that opens the appetite for other documentaries. And I think that's a good thing. You know, so Tiger King probably brought in a generation or a bunch of audience to the concept of a docu series. And now there'll be more interested in might be watching, you know, one of your projects or college behind bars or something along those lines, because they associated the docu series. I could jump into them. It just yeah, I think it helps everybody. It does help everyone, even though some of it might be more exploitive. It does open up hopefully the audience to other great documentaries.

Lynn Novick 1:02:15

I agree. And to get back to what you said at the beginning. It's about real people. You know, so there's something absolutely fascinating about this is not an actor, right? So person doing their thing, whatever it is. This is not somebody wearing a costume,

Alex Ferrari 1:02:30

right? Or superheroes outfit or a giant lizard or giant girls. But yeah,

Lynn Novick 1:02:36

there's something is absolutely fascinating for us as human beings to be eavesdrop on somebody else's life.

Alex Ferrari 1:02:42

What's the voyeuristic is that voyeuristic thing that you know why voyeurism is such a powerful thing. I mean, Hitchcock knew that extremely well.

Lynn Novick 1:02:50

I know, I was thinking

Alex Ferrari 1:02:52

extremely well. We're all fascinated, like, Who's What? What's going on behind that closed door out there? What's going on? And that's what documentaries do. They peek you through the door like yours. Like in Hemingway, you're seeing things that were not made public, you know, and you're seeing things behind the scenes that are really, you know, almost voyeuristic in a way. I had one other question for you in regards to because the kind of the kind of documentary you are is you tell the story. You tell the truth. You put it all out there. But there are documentarians and filmmakers who put themselves in the story. They're the guy they're the narrator. The supersize me the Michael Moore, the michael moore's very famously, who put themselves in the documentary, how do you what do you feel about those kind of stories? And that kind of, I mean, just not specifically just filmmakers, but just, it's a different kind of documentary?

Lynn Novick 1:03:41

Yeah, it's wonderful. I mean, I think in a way, it's very honest, because then you know, who's telling you this story? Here's the guy or the woman whose story this is there's no kind of objective, anonymous, invisible force of story, God, whatever. It's, here's the person who's you know, Michael Moore is going to walk you around and tell you what it is. And I think if it works, it can be really powerful. I actually admire filmmakers for being brave enough to put themselves in. And, you know, be in front of the camera. I hate to do that. My partner is a psychiatrist. His name is Ken Rosenberg, and he's also a documentary filmmaker. And he when I first met him, which was five years ago, he said, I'm working on a film. And it's about serious mental illness in America. And he, he filmed at the LA, the emergency room in LA for a number of years, and people who were in psychotic states, and then followed them over time. And as he was working on the film, he realized he needed to put himself in it, which is why so he ended up basically narrating it and being on camera, talking about his own story of his sister's descent into schizophrenia and how she died and how he'd been carrying this burden as a doctor who couldn't help his own sister and how many families suffered so and he very consciously chose to use himself and his story. To kind of ground the film, and so then, you know, well who's telling me this story? And why should I care. And it was, you know, he didn't start out wanting to do that. But it was a really powerful device was also helpful for him to exercise his own demons and tell the story. The film is called Bedlam. And he got to DuPont last year. I'm very proud of him. It's Yeah, so but it was a really good example of the power of the on camera filmmaker, being inside the story and helping you guide you through it, and also being really transparent about why this story is even being told in the first place. So it can really work well.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:34

Yeah, it's a way to connect the audience to the subject matter sometimes, because something's like jazz or baseball, you don't need someone walking you through it. It's not a weird, it'd be weird. Like, Hey, hi, how you doing? I'm Alex. And we're gonna back in the day like that's just like, it seems very kind of kitschy, and it doesn't really like something you would see on Sunday at like three o'clock on. Unlike you're not even local public access, it would just be like, it's a weird thing. But certain topics like supersize me was all about him going through the process. He's the subject, you know, which was, I mean, I mean, he literally changed McDonald's. I know. Like, it was remarkable, that whole world. And I have a couple questions I want to I asked all my guests. What advice would you give a documentarian wanting to break into the film business and into the business of making documentaries today?

Lynn Novick 1:06:29

I'm of two minds.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:31

Let's explore less explicit. Yeah.

Lynn Novick 1:06:34

You know, I think, you know, be sure you're passionate about the story you want to tell? And why you want to tell it and really drill down on that, why you care about it, and what you can say that hasn't been said. And then most important, how will that affect the people who you're going to be filming? which is sort of back to our Tiger King point? You know, is this going to be something that will, your subjects will be okay with when it's over. And I'm not talking about expos day of, you know, corporate malfeasance. If you want to make a documentary about Purdue pharma and the sacklers. Go for it. They deserve whatever bad things can happen to them as far

Alex Ferrari 1:07:13

as I'm concerned.

Lynn Novick 1:07:14

Right. But if you're talking about ordinary people, and you're gonna write so but if you're gonna film just your neighbor, and their relationship with their dog, or something like the truffle hunters, let's say, you saw that right? So is this, why are you doing it? And what are you trying to say? And is it honorable to our larger point, but if you're passionate, and you have a story that you think needs to be told, then you should go for it.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:39

And it's so affordable to do it nowadays? I mean, the cameras are expensive. It's super inexpensive and made before you had to get the film camera and the dad and all that stuff. I'm assuming you guys shot some film back. Yeah. And cut it on flatbed. And

Lynn Novick 1:07:54

the four guys who repaired the scene bags went out of business about 20 years ago. But yes, yes. infrastructure of that world. So, you know, yeah, I think the mode of production is much cheaper and more available and more democratized. You can film it on your iPhone, you can cut it on your laptop, you can put it out on YouTube, you know, so the barrier to entry is zero. So it's more just, is the story worth telling? Is it really important? Is it gonna be worth your spending X amount of time of your life to tell this story?

Alex Ferrari 1:08:22

Now, what is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film industry or in life? Oh, wow.

Lynn Novick 1:08:31

That's such a profound question. Not sure I can answer it. A few things come to mind. The longest to learn. I've learned a lot of lessons. So I, you know, pop this, I don't know if that took me the longest to learn. But it's something I hold on to is how important it is to just be present. And especially now, it's so hard because we're so distracted. I haven't looked at my phone the entire time we've been talking. And that's maybe a record, you know. So, to really, but that's, you know, I'm here with you. I'm not doing anything else. And that's great. We've had a great conversation. And I think we lose that so easily. Just, you know, yeah. How often have I been doing something and I get distracted, and then I'm lost. And then I don't come back to where I was. And so trying staying focused and being present. And just letting things happen because you are present is really, really important. And I think it's it takes a lot of discipline to do that. Especially now it's really really hard.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:35

And three of your favorite films or documentaries of all time.

Lynn Novick 1:09:40

Oh, wow. Okay, well films of all time. I don't have the Godfather way up there on high on the list. Yes. Which, you know, I don't know that's a desert island movie. I could watch it over and over again. So there's there's a few others. I've just documentaries. There's so many I don't know. That's really hard to say. Wish I was prepared for that I have a list.

Alex Ferrari 1:10:02

What comes to what comes to the top of your head?

Lynn Novick 1:10:05

Well, interestingly, under Francis Ford Coppola sort of genre the hearts of darkness. As such, it writes

Alex Ferrari 1:10:12

Eleanor Eleanor Coppola hits Wow. Oh my god, what

Lynn Novick 1:10:17

an amazing documentary amazing documentary. It's about the making of Apocalypse. Now, for anyone who doesn't know an apocalypse now, it's kind of a flawed film, but has moments of brilliance in it. And her telling him how challenging that was. I wasn't a filmmaker when I saw it. But it really stuck with me, eyes on the prize, which was a series on PBS in the 80s, about the civil rights movement, had a huge profound impression on me because it was first time I'd seen that kind of storytelling, just regular people who were witnesses and participants in history, telling their stories. It's such an important historic experiences of our country that I had read about in books, but I did not understand and seeing eyes on the prize brought that epic time in our history, vividly to life and just indelible ways. So that's way up there on the list for me,

Alex Ferrari 1:11:07

well, Lim, it has been an absolute pleasure talking to you all things documentary, and I tell everybody out there to please go watch Hemingway and all of your films, honestly. I mean, if you if you've got like a year or two to put away cuz it's gonna take you a minute to watch it. How many hours have you like, I read somewhere, like 80 hours or something like

Lynn Novick 1:11:29

that, if you like that, but it's been 30 years.

Alex Ferrari 1:11:31

Right? So I mean, it's not like you just did that last week. I mean, it is, but but Thank you, sir. Thank you so much for doing what you do and fighting the good fight as a documentarian and telling the truth out there and helping get a little bit bit of clarity on your subject matter. So thank you so much. I appreciate it.

Lynn Novick 1:11:48

Thank you, Alex. It was a great conversation.