Today on the show we have million-dollar spec screenplay writer, director, showrunner, and author Jeffrey Alan Schechter. Jeff has been beating up stories for over twenty years. He is a WGA, WGC, Emmy, and BAFTA-nominated writer, a Gemini award-winning producer, director, and a million-dollar spec screenplay writer.

Jeff’s first credits were in action films such as BLOODSPORT II, THE TOWER, and STREETKNIGHT. Turning to his love of family films, Jeff sold his spec screenplay LITTLE BIGFOOT to Working Title Films and then did a rewrite on THE AMAZING PANDA ADVENTURE for Warner Brothers which led to him working on DENNIS THE MENACE STRIKES AGAIN.

Jeff followed this with another rewrite, this time for Warner Brothers’ IT TAKES TWO. Following this, Jeff’s spec screenplay STANLEY’S CUP was bought by Walt Disney Pictures in a deal worth over a million dollars.

Jeff next rewrote I’LL BE HOME FOR CHRISTMAS for the Walt Disney Company and wrote the TV movie BRINK! For the Disney Channel and for which he was nominated for the Writer’s Guild of America Award for Outstanding Television writing. Jeff also wrote THE OTHER ME for the Disney Channel as well as BEETHOVEN’S 3RD for Universal Studios.

In television, Jeff has written and executive story edited dozens of episodes for series such as THE FAMOUS JETT JACKSON, ANIMORPHS, MARTIN MYSTERY, TOTALLY SPIES, TEAM GALAXY, GET ED, FREEFONIX, DI-GATA DEFENDERS, HOT WHEELS BATTLE FORCE 5, and JANE AND THE DRAGON. He’s written both DTV productions for the Care Bears; JOURNEY TO JOKE-A-LOT and THE BIG WISH MOVIE, the latter for which he was nominated for a 2005 Writer’s Guild of Canada Award.

Jeff was an executive story editor and director on the Hit Discovery Kids/NBC series STRANGE DAYS AT BLAKE HOLSEY HIGH (aka BLACK HOLE HIGH) for which his work was nominated for two Emmy Awards for Outstanding Writing as well as a BAFTA Award for Best International Series. Most recently, Jeff created and was the showrunner of the sci-fi procedural drama Stitchersfor Freeform which ran for three seasons and which took place in the proverbial ten minutes in the future.

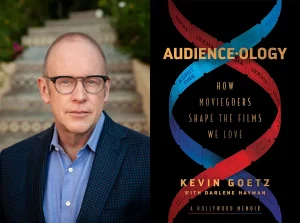

In publishing, Jeff is a co-founder of the award-winning ebook publisher PadWorx Digital Media, and his book My Story Can Beat Up Your Story: Ten Ways to Toughen Up Your Screenplay from Opening Hook to Knockout Punch was published by Michael Wiese Books. Jeff is hip-deep in several other screenplays, television series, book projects, and software ventures. In his spare time, he’s married and has 4 kids.

Enjoy my conversation with Jeffrey Alan Schechter.

Alex Ferrari 0:52

I'd like to welcome the show Jeff Schechter, man, how you doing my friend?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 3:58

I'm great. It's so good to talk to you. Yeah, man.

Alex Ferrari 4:01

It's been we've been playing even Skype tag for quite some time. So I do

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 4:07

well, it's apparently between the two of us. You're the busy one. I'm sitting here like like this for months going. When's Alex gonna call? Yes, I'm

sure that's exactly Schecter.

Alex Ferrari 4:20

Obviously, that's what I picture all my guests do it. No, I'm joking. No, but when, when we when we logged on to Skype, you know, we're like, you know, brothers from another mother because you've got all this amazing geek stuff in the background for people listening. He's got Star Wars statues and Marvel statues everywhere. And it's just, it's, it's nice. It's nice to see, to see that as well. So, before we get into, how did you get into the business, um,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 4:48

it was kind of one of those things where I always knew I wanted to be a writer. I mean, I made which was really, I mean, you know, I've got four adult kids and they both asked me like, when did I What I wanted to do because, you know, they're on various phases of the summer figured out exactly what they want to do some haven't. And it's like, I don't know, it's I don't remember a time when I didn't want to be a writer and didn't want to write for television. And you know, so it was sort of just like everything I did. Starting even in junior high school. Going into high school, I was writing stuff, I was writing my own plays, I was directing them I was making short movies, you know, with my friends in the in Brooklyn, and and then ultimately came time to go to college. I just knew I was going to go to film school I applied to State University of New York College at purchase. So SUNY Purchase. were, you know, had back then I was late 70s. You know, they're the people who came out of purchase were people like Stanley Tucci and being rains was nice was there for a while, you know, in the acting world. They're acting I think Hal Hartley came out of SUNY Purchase, Charles lane. Parker Posey was there. So you know, there was a sort of an up and coming kind of vibe to the school, and just went through film school there, got out had a great mentor at school who helped get me into into editing. And so I worked in editing for a couple years in New York while still writing screenplays and then just moved to LA I read them. I mean, Goldman's book adventures, a screen trade, great book, right? It's a great book. It's any anyway, he had a chapter. He, you know, the, the early parts of the book, before we started talking about his specific movies, the early parts of the book, how chapters are broken up, like, you know, producers, directors, actors, right, you know, and then as the chapter is called, you know, LA, and the chapter begins, and I'm paraphrasing in perfectly, but something like, I find Los Angeles to be a dangerous and potentially very harmful place in which to live. And I suggest that anyone seriously considering a career as a screenwriter move there as soon as possible.

Alex Ferrari 7:06

2023 or

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 7:08

24 year old me reads that and like, okay,

Alex Ferrari 7:11

where's my ticket? Where's my ticket? Yeah.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 7:14

Then everything add into a Buick lesabre and drove cross country.

Alex Ferrari 7:18

Before I got before I got here. I've been here about 12 years and and I lived on the East Coast as well. And friends here, we're like, the only thing you'll ever regret about moving to LA is you didn't do it sooner. And it's it's it's true. Once I got here, I completely understood what they were saying.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 7:33

It's industry town. You know, it's like the whole town

Alex Ferrari 7:35

was built. Like I always say, you could take the film industry out of New York and New York, still New York, you take the film industry out of LA. I just not the whole infrastructure is built around the industry. Right?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 7:47

Yeah, for sure. For sure. That's how you want to go if you want to go into auto manufacturing probably still have to go to Detroit. You know, right. If you're

Alex Ferrari 7:55

if you're if you're me, imagine a Silicon Valley left San Fran. The whole the whole, the whole town would just collapse on itself.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 8:03

Yeah. Yeah. You know, that would be the time keep keep your eye on that. Because that's the time to buy in Palo Alto.

Alex Ferrari 8:09

Yes, exactly. Buy as much as much real estate as you possibly can

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 8:12

as market my friend.

Alex Ferrari 8:15

At that point of the game. All right. So So before we get into your your awesome book, I need to ask you a very serious question. Bloodsport to

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 8:24

Bloodsport to the Citizen Kane, Bloodsport franchise.

Alex Ferrari 8:27

I mean, obviously, I actually am not only a huge fan of Bloodsport one because I'm from the 80s though I'm sure if I watched it again right now. I would not think it was the best movie ever made at the time. So it lives in my mind as what it was when I saw it. And when I saw that you wrote the sequel to that because Bloodsport one was a fairly big hit. At the time.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 8:55

It was it was a big hit. And then you and then they call you up and go. And they call it an ATM. I mean, it was Yeah, it's it's it's one of those cult classics. I mean, I haven't watched it in I don't know 20 years or something like that. But it's it's definitely one of the I mean, I still talk to the you know, the the producer mark this out. You know who you know who produced the movie. I don't think he's directed at either I think kickboxer but I know somebody else directed, Bloodsport one. Anyway, and you know, he's still like, a blood sport. Yeah, blood sports, still paying the bills.

Alex Ferrari 9:32

It's amazing. It's amazing. It's one of those things. And so then how did you get the call because that and then that's it. That's a pretty big first because I saw it was like one of your first writing credits, right?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 9:43

That was the first thing that was the first like, that'd be ga guy. How'd you get that? How'd you get that is a crazy story. I had an agent at that time. Who? Well, I was studying karate. I was a black belt in Taekwondo. back then. And I guess, technically, I'm still a black belt though I can I could demonstrate one kick for you. But then you have to call 911. right afterwards.

Alex Ferrari 10:09

In your mind, in your mind, you're a black belt.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 10:12

Oh, wait, let me do it again. Yeah, that was a good one. Okay. So I was a black belt, and I, I was just quit my, my regular job, I had a, this was going 89, I want to say. So maybe just going into 90, and I've gotten out to LA and 84. So I have here six years and writing a bunch of scripts. And we've got, you know, finally got a good agent, and some good specs, features. And then I was working, I was working like full time at something. I was managing the karate studio for a while. And then I was doing industrial videos. And, you know, when I was working for a sales company, I was doing these industrial videos and sales training. And, and the guy that I worked for, had this, he had all these interesting business theories that were actually Yeah, don't get no hate mail, please. But there's actually stuff that was distilled down from L. Ron Hubbard, who had a lot of business theories besides his Scientology stuff, right? He was used to business organization.

Alex Ferrari 11:24

I mean, as you can tell, obviously, because Scientology is a very powerful organization. financially.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 11:29

Yeah. The run organization, right. So nice. But so so one of his principles that he had was that if you do something part time, you get part time results. If you want full time results, you should do it full time. So I've been, I felt that I had achieved much like as, as a successful part time writer as I could possibly be, I had an agent, I was kind of optioning scripts for $1 or $10. I was able to go on meetings every once in a while, right? So I felt like doing it part time, I'm getting my part time results. So So I quit the job doing these industrial videos, and decided to dedicate six months to nothing but writing. Um, so the guy gave, I gave them two weeks notice the guy says, hey, look, you know, we need some more time for releasing, you can give me a month, send me a short, right. So that was like around Thanksgiving. So I gave him the month and in that first month, I write a script, I'm going this is amazing. I can I can I knew I could support myself for six months, you know, without having to find another full time job. When you go Yeah, I'm going to support myself for for six months. And and you know, this way I can write a script a month and it's going to be I'm gonna be

Alex Ferrari 12:43

a big festival. It works. Absolutely,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 12:44

yes. Right. So, so wrote that first script in that first month, you know, had my last day at work. And then right around that same time, I started getting involved in Orthodox Judaism, because I was I was conservative, Jewish, Jewish, but getting involved adopt Judaism. I spent the next six months just learning about you.

Alex Ferrari 13:04

So you were procrastinating as a writer, what a shocking, shocking

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 13:08

religious procrastination mode.

Alex Ferrari 13:12

Instead of Netflix, you went down the Orthodox Jewish route. Okay, fine.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 13:16

I was able to say yes, I'm procrastinating, but it's because God wants me to. Exactly. So. So anyway, so the six months so five months goes by I've now like almost completely depleted my my account. And I'm like, Okay, this, I'm just gonna have to go get another part time job. Right. And which I wasn't worried about a single living on my own. It was in the

Alex Ferrari 13:37

ramen, ramen noodles.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 13:39

freaking out. Anyway, so my grandmother at that time did your story.

Alex Ferrari 13:45

I mean, you can get to Bloodsport whenever you want. I've always been

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 13:51

Okay, I'm gonna get there. But it's just it's you asked. So, I hope you've learned your lesson about asking me any question.

Alex Ferrari 13:59

Yes. Fair enough. Fair enough. I'm seeing the pattern sir.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 14:04

I've lost track of where we were. Okay. Let me start again, grandma. Anyway, so so your grandma so Grandma, grandma had always threatened to take me on a trip she was not well off to travel says okay, here's here's a you know, small bucket of money. Why don't you go on a trip so I said, Okay, I'll take I had friends in England friends in Sweden. Okay, so I'll go to you know England for a week Sweden for a week and then I'll go to Israel for two weeks and then I'll come back find a job and you know, keep pursuing this as a part time thing. I do my one week in England, and I literally am walking through the apartment door of my friends in Sweden when their phone is ringing right now. This is pre cell phone pre now. Right so their phone is ringing and it's like you know, I I apologize in advance to your Swedish viewers. But you know, real quick and talk or whatever the hell they say in Sweden and and stuff like that. Yeah, hold on one second. And they hand me the phone. They go. It's your agent. cracking down on it because I gave her my itinerary. She tracked me down. And she said, she said, there's an open writing assignment for Bloodsport to the producer hadn't read one of my spec screenplays, which was sort of a cop, you know, a cop action kind of screenplay. And any would like to meet you to see if there's a fit for Bloodsport, too. I'm like, I'm just starting the second week of a one month trip, you know, will this job be available? When I get back in three weeks? She said, No. I went, Okay. So I will come back in a couple of days. Alright, so I took literally whatever little money I had on the trip and whatever money I had in the bank and bought the only took ticket I could from Sweden on short notice, which is a one way business class ticket if you want to style. Oh, my God, well, yeah, we're gonna go out go out big. So. So cat got back to LA and met a couple of days later. And she just said, there's no way I'm not going to get this job. There's no way I have to get this job because I spent more than the money I actually even had. So I got to meet the guy. And, you know, my, my Brooklyn accent is behaving itself. Well, at the moment, but, but the guy I met with great guy named Mark de sal. He's from New Jersey. So and he has not gone through the pains that I have to get rid of the accent. So I sit down in the offices, yeah, it's really nice to meet you. I'm going, Hey, it's nice to meet you, too. my accent starts coming out. And we're talking and we joke and we just immediately hit it off. It was just like one of those things. where, you know, we just just really clicked right in the eye, like, you know, to who, you know, two guys from back east? And, yes, backgrounds and stuff. And so all throughout the meeting was going yeah, this is great. I really loved the script. But you know, I gotta, you know, I got to talk to some of the writers. And I'm like, leaning in, I go, No, there are no other writers. Three or four times throughout the meeting. Yeah, no, no, this is fantastic. But you know, I'm still talking other writers. No, there are no other writers. And then, so the meeting finishes, I'm feeling really good about it. But then I raced over to the karate studio that I was, you know, been training at and because I had helped the, the instruct the the master at the studio, right, some karate books. Yeah, which is, I think also helped with the Bloodsport, obviously. And then there was some picture in one of the books of like me doing this, like 12 o'clock sidekick back when I could lift my leg over my head, not by another couple of guys off of me. And I literally wrote in the gap between my bottom leg and my top leg, there are no other riders and ran it back to his office and left it for him with his assistant, that's a man got the job the next day.

Alex Ferrari 18:03

That's awesome. That's an

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 18:05

awesome car. It's a combination of, you know, serendipity. Yeah, yes, Deputy two boys from back east, but but I think the, the little if I could presume to make a learning moment, out of that incredibly long, potentially boring story, it's that I was I was just willing to do whatever it took to do it. I mean, literally, like, Oh, I gotta buy a, you know, $3,000 ticket with money, I don't have to get back to LA, well, this is what I want to do. This is what I got to do. Right? So it plays into this. And that you got to be willing to commit, you got to, you know, a lot of people have, you know, dreams, you know, and you know, a lot of people have goals. And there's a difference between a dream and a goal. Right? So, you know, I had a job, it wasn't my dream to be a writer, I had a goal of being a writer, and this is what you have to do. That's what you have to do, you know, and you have to just suck it up. And, you know, and put in

Alex Ferrari 19:11

extra risk and take the risk and take it because it was a it was a risk, like, you know, in general, it's a massive risk. So you had no guarantee you were gonna do it and you were like, Look, I'm gonna lose the rest of my European vacation. And, and then I'm also gonna have to spend $3,000 I don't have for the bear the risk. Also, it was a different time. There was it was a different time. And you know, I wouldn't do that today.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 19:35

Right. And that's, and I was I was gonna say that it's not like I was there. You know, I was what 2829 you know, you know, single, right, my monthly expenses, were maybe 12 $100 a month. You know, it's like, you know, it wasn't, it wasn't such a thing like now it's like if I was on a European vacation or one of your big European vacation with my with my wife. And that my kids and I get the phone call, you know, it's like, you know, I'm not saying Honey, you know, I'm going to go back to LA you You stay here.

Alex Ferrari 20:09

Yeah. I mean unless obviously unless Kevin fee and then

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 20:13

yeah then it's right that's a much different I did on a we're on a cruise, you know, last summer and and there was a you know a showrunner position it opened up on a on a TV show and I had to talk to the show creator and you know and I said it's a guy I knew I didn't get the job but that's because like I'm in the middle of like, you know the Baltic Sea or wherever the hell we were trying to do a Skype call with like international Sure Sure. Sure. Like he couldn't hear me I couldn't hear him suffice it to say I did gotcha. I did not get I did not jump off the ship, swim to shore and take a plane back.

Alex Ferrari 21:00

So let's get to your book because you know, one of the reasons I wanted to have you on the show was out of the in the screenwriting space of screenwriting books, yours definitely sticks out by its title, my story can beat up your story. And it's a fairly violent title, sir. It's a you're obviously so obviously, all that karate is seeped into your screenwriting, and your Bloodsport

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 21:26

just welling up.

Alex Ferrari 21:27

So why did you write first of all why did you call it that? And secondly, why did you write this? What what caused you to write because there's a lot of screenwriters in Hollywood, there's a lot of people who've worked in television, but there's 1000s of them. But very few actually decided to sit down and write about the craft or tried to pat paid forward in whatever they've learned along their their journey.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 21:45

Right. It's a great question. The the desire to write the book came from now a bit of a gearhead, you know, like, like a bit of a science, you know, not honestly, science background, I think that's, that's giving myself too much credit, but certainly a huge interest as an amateur in science and physics and, and how things work. And, you know, my favorite fondest memories, when I was a kid was getting, you know, some broken piece of electronics and attacking it with, you know, a screwdriver and just dismantling it and trying to understand how it works. So, so I've always was fascinated with how do stories work? Just how do I reverse engineer a story? And I had a friend, guy named Gil Evans, who's also writer, and he and I would have these conversations back and forth. You know, how about this happens? Oh, somebody has this theory. Oh, there's this seven act structure? Oh, it's a sixth structure. Oh, there's 22 steps. So there's that. So we would just go back and forth. And, you know, and try to figure out sort of the structure stories. And I think the biggest aha moment I had was Bloodsport to all roads lead back to Bloodsport obvious that they said okay, well, you know what I want to you know what I'm going to structure Bloodsport to let me let me take two movies, you'll get them from blockbuster, put them in my handy dandy VHS player. And just just do like bullet points, you know, plot points, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So I did 48 hours, and I did lethal weapon. Right? So I write it down. I wish I had those papers. It was kind of fascinating. So I wrote down blah, blah, blah, that plot points, 48 hours. And again, it had 44 plot points. And well, that's interesting, then I did leave the weapon, but below the 44 plot points. So I Whoa, that was interesting. Right, the 44 plot points. And they said, Well, can I set it divide those other? Was there a sort of a commonality on how those were laid out? Right. So I started saying, Oh, well, the first section is kind of this. And the second is the four act structure with the biting point that yes, so things started making themselves known to me, and then I would bounce it off my friend Gil, and he'd be like, Oh, this is really interesting, because I just read this book, called the hero within from Carol Pearson, that talks about the ark types that, that go into storytelling. And then I started examining films with these, from the lens of these art types is like orphan wandering war and martyr. And, and, and it laid out, you know, on those films, and then I started breaking down other movies and you know, 43 plot points 47 I was all in and around 44. So So I think in your case, I'm really onto something here. So, so just from my own writing my own benefit, I just tried to codify it in some way. And better that ultimately led to me. You know, I was kind of dabbling in programming at the time. And by programming I just mean like, database programming. So to access I said, let me see if I can create for myself a little template that I could use for story structure with Microsoft Access, just kind of from my own streamline my own process. So Did it and we had this like in the, for arc types and the 44 plot points, and what's the nature of those first 12 plot points?

And the reversals that happen after the end of Act One, and the central question that comes up, and just everything that that I had learned, and you'll find myself in, in conversation with the, with my friend, Gil, and develop this, this kind of like interactive database that was sort of fill in the blanks and, and you have a well structured story, because because the structure wasn't just working for Lethal Weapon and Bloodsport to and and, you know, and 48 hours, it was working for Star Wars, and it was working for, you know, I was writing, you know, kids movies at the time was working for Dennis the Menace to and you know, the Wizard of Oz, and it just, it seems to just, you know, it started feeling, you know, if I can, you know, in my spirit of self aggrandizement, it started feeling like, like, I might have actually accidentally stumbled onto like the unified field theory of story structure. Okay. And so, so I developed this piece of software for my own use, and then moved to Canada going, you know, towards the end of the 90s. And because the whole immigration thing, I couldn't, I couldn't work for the first nine months for Canadian companies. So I'm saying I'm going, what am I going to do, I had still had some contracts from the States, I was writing a picture for universal. And I was like, Well, what do I do with all my extra time on waiting to qualify for Canadian work permit? I said, Well, you know, I had the software, let me figure out how to distribute it. Right. So you know, so that became like, my side project, I was gonna market this story structure software. But it is any good piece of software, you know, comes with a instruction manual. So I had to now write down the instructions for it, you know, which meant that I had to start explaining the theory behind the instructions. And so suddenly, I had this instruction manual, which is like 50%, of a book on screenwriting. So ultimately, you know, about 10 years later, or so, you know, I was thinking, I should just turn this into a book, because everybody who got the software loved it, and everybody who was just even read the instruction manual, and be like, wow, this is cool, you should make this into a book. So this is kind of it started from my own lazy ass, you know, I don't want too much when it comes time to work. So I went from that to you know, here's a structure I can use for myself into, you know, something I can sell to others versus and then they just, they turned into a book as well.

Alex Ferrari 27:47

So then, so now you have the story structure, you have this, you you've broken the unified theory. Right? You, you've gotten to black matter of story. Essentially, I am I am also an amateur science geek as well, a little bit. So it's, I understand. But so you started I'm sure you've read a handful of screenplays in your day. So you've probably read a bunch what are the most common mistakes you see in screenplays and And specifically, from first time writers but also from even experienced writers, people just writers in general? Because, you know, not everyone hits it out of the park every time.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 28:28

Yeah, for sure. No, no, nobody does the, the I think the biggest mistakes that try to say it in a way that's that's not that's not offensive,

Alex Ferrari 28:42

be offensive, it's okay.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 28:43

The barrier for dialogue, right? Or their ideas, you know, are not commercial or you know, to be harsh, they just suck. Right? That that's not a mistake, that's just taste, is it not, it may not even be taste, it's just, you know, you just you've hit the wall on whatever your natural ability is, you know, I, you know, if somebody if somebody says, you know, what's the biggest mistake you see with amateur amateur mathematicians, you know, and I be like, Well, you know, my inability to do any sort of high level math is not a mistake. It's just, it's a limitation, right? So, so stuff that can't be learned, you know, you'd kind of just stuck with so taking that out, I would say, oh, bad characters or, you know, bad dialogue. I mean, everything could be improved, but, you know, you have to cross that threshold and to something unique and different. But the the kind of the unifying mistake that I see a lot is bad structure. Because part of what my study on the subject has shown me is that we are wired we have a biological imperative. Storytelling, and stories that are told in a way that our brains are physically constructed to understand have a better have a deeper resonance to us than stories that come that try to, you know, like, if our brain has circular story receptors, and something's writing, you know, plot points that are squares, they're not going to get into our story receptors. And yeah, I mean, we've all had that experience, you see a movie or a TV show, you know, something like that, that really didn't sit right where I didn't like that. I'm not even sure I can even negotiate why I didn't like it. I can tell you why it's because because the structure, some of that some aspect of the story was trying to force its way into your brain, and it blew everything up on the way in, you know, and then your brain starts trying to churn and understand what the hell was that all about. And, you know, and and it just leaves you with a very unsatisfying story experience. So the biggest mistake I see is people just don't understand structure well enough and structured doesn't have to mean formula. But I haven't done this exercise yet. I mean, I was crazy about the movie parasite. But I can assure you, that, that if I sat down and ran, ran it through, you know, my understanding of structure and the whole, my story can beat up your story approach to telling, it'll, it'll all film, it'll fall out in, in line. So and nobody can accuse, you know, parasite of being like a formulaic movie in any way. So what structure does is it just, it gives you a, it gives you a wrapper around which you can let your creativity and your innovation and your, your, your personal flair for storytelling shine. But you don't have to reinvent you don't reinvent structure. Every time you sit down to write a screenplay,

Alex Ferrari 32:05

it's, I always use the analogy of, of a house being built, it's the frame. So you, you know houses are going to be houses, you can't build the foundation on top of the roof, it's, that's just not you need that, there is a basis of how you build that house. And it's always going to be the same no matter what you do, there's a foundation, there's walls, there's a door, there's a roof period, what you do inside of that is where the magic happens, that's where the architect comes into play, that's where you could do other things within it. But those basic building blocks cannot be adjusted, because that's just the way the way it is you can try to put the foundation on top of the roof, let me know how that works out. And then you get you know, some some other movies that we will remain nameless, that tried to change the structure. And you're very right, like you watch. You know, you watch a film, like the room. And, and you you watch that, and obviously that that movie is so far beyond any sort of the foundation is on top of the roof on a film like that. And also, the dressings inside are all thrown around and everything. So it's upside down. But he's transcended, he's walked into the multiverse, he is now in another dimension and is now because entertaining on a completely different level for for many people, and that's very rare.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 33:32

Well, it's, it's interesting. I mean, it's the the analogy with the foundation and the roof, and everything is a good, good analogy. Because even like in my book, you know, like going back to those 44 plot points. It's the first well make up act one. And those are the ones that get really specific about the, you know, Hero villain or stakes character, you know, you know, it's a very specific flavor. After you get past those first 12. Like the, you know, the remaining 32 are much more generalized. You know, it's like, you know, you know, seven pairs of Yes, no reversals, and I don't say, you know, this Yes, no reversal, the, the stakes, excuse me, the stakes for the tertiary characters increased by 14%. You know, it's like, I don't I don't drill into it. Because that that's mind numbing. Right. And you're an unhelpful, but the first 12 are super important. That's the foundation of the house, and then you know, and still, we even listen that, you know, it's still gross. And I should just add, you know, that, that the, my approach to storytelling is not like, you know, because it's, I would hear a lot. It's like, Oh, so every, every movie has to every movie, you know, you know, is

Alex Ferrari 34:48

your page on page 16. This happens on page 18. That happens.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 34:52

Yeah, actually, I try not to get that specific, but it gets pretty specific, right? Yeah. So yeah, so no, not there are a ton of really good movies out there that probably have nothing to do with my system at all. So my, my, and this is I know this is yo yo, indie film hustle. Right? So, you know, indie films, you know, can be a little bit more freewheeling, you know, and experimental that what I'm talking about, you know, my goal had been to be a Hollywood hack from day one. So, you know, so what I'm describing is a very specific, here's how commercial movies you know, work. And the, the reality, you know, it's sort of a chicken and egg type of thing, you know, am I saying that, you know, all, you know, all good movies are all well structured movies, follow my system? No, no, probably not. You know, do all movies that follow my system, end up with good structures? 100%. Yeah. And then then it's, you know, now you're stuck with your dialogue and your character,

Alex Ferrari 35:59

theme and plot. And, at

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 36:00

least at least, we took the biggest stumbling block off the table, which is structure.

Alex Ferrari 36:06

You know, the one there was one movie I saw years ago, and I haven't seen it since because it was, so I found it to be just absolutely horrible, which was up but it was a huge monster hit, which was Twilight, the original Twilight film. When it came out, it was such a big hit, I just needed to go see it. And I watched it. And I found it to be horrendous. And I because the the main villain didn't show up until 20 minutes before the movie ended. Like, there was no even conversation about this guy. Until then, it was all about the love, you know, the back and forth pining? And then I understand why it made so much money because the girls that went to go see it, they wanted to do that. And they it fed into that demographic perfectly. But the villain, like the villain, and shelf is like literally 20 minutes to the end, he showed up I'm like, What? Am I the only one who sees this? Like, there was no antagonists for 80% of the movie, so I couldn't relate to it. So that just that we wiring thing that you were saying it was like, short circuiting My mind was that I just kept seeing like, why did everyone like and I'm like, okay, not everyone but you know why it was such a big hit? That's

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 37:13

right. That was that's kind of like a there's a two part thing with that which is that the you know, like when doing my analysis of movies, I never do sequels or movies derived from pre existing material us because you can't learn anything because they have such a built in audience

Alex Ferrari 37:33

and there was a twilight books Yeah,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 37:34

yeah guy you know, you know if if George Lucas you know, released though, I guess the Star Wars was originally Yeah, is getting a little bit you know, long in the tooth you know, at least you know, as far as critical success but maybe not. But, but but you know, if if another Star Wars movie came out, you know, it's going to make a certain guaranteed amount of money no matter how bad it is. And I mean, you know, it's just it's got a built in audience so I find for educational purposes you can you you want to you know, you can learn a lot more from analyzing Toy Story than you can from analyzing Toy Story for right now. What you get out of it, boy, sorry for man, for all I know, may maybe made more money than it did or so right. So he said, Oh, well, therefore, let me learn from Toy Story for now. It's got a 30 year built in audience right. You know, it's like God,

Alex Ferrari 38:35

is it that launch Jesus? It is as close to five I think, yeah, so like 25 years

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 38:41

Jesus. So it's like, so you can't you can't learn anything from Toy Story. Or it's like

Alex Ferrari 38:47

a while but Wally, but while you can.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 38:53

Yes, exactly. Exactly. Correct. Right. So something like that. Right. While he too. You wouldn't be able to learn as much from I don't think it would I wouldn't say Bali too. But

Alex Ferrari 39:01

I actually I would practice

Unknown Speaker 39:03

revenge

Alex Ferrari 39:04

to the Electric Boogaloo.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 39:08

Yes. Okay. So, so a lot of the you know, whenever I know, that was like another real big, real big in it, not innovation. But the aha moment for me was looking at like a I go through Internet Movie Database and look at the top 50 grossing movies of all time. And but parse the list. So I took out sequels, I took out reboots, I took out anything that had any sort of brand awareness, and said, Now you know, these and those, those top 50 of all time might have been distilled from the top like 300 movies of all time based on box office, because I had to get down to the 50 original movies. So liar liars and the you know, the Star Wars is the original

Alex Ferrari 39:55

Star Wars. So let me ask you a question. So I always love asking about this because I avatar. avatar wasn't original concept, original world, no pre existing, fairly risky film to put out and I argue still that there's only probably one man on the planet who would have had that opportunity then I don't think they're given Spielberg 500 million to do the design and even in or Scorsese or any of these guys, so there's very few shortlist. But that movie, obviously was the biggest movie of all time, arguably still is based on inflation and all that kind of good stuff. Well, if you want to go back to Khan with the biggest one, it's Snow White and Snow White. Yeah, and you know, those kind of stilted but arguably speaking, it's one of the biggest cultural hits of all time.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 40:45

Number one for many years for Yeah,

Alex Ferrari 40:46

exactly. What was it about that story, which it did get nominated for Best Screenplay, and Best Picture, but the screenwriting community I remember just destroyed it because it's burned. Golly, it's Dances with Wolves. It's this and that, like he said, they just go back and I'm like, Yeah, it is. ferngully Yeah, it is. Dances with Wolves. I mean, it's, it is Dances with Wolves. But a much cooler version of Dances with Wolves

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 41:14

I've ever seen ever seen the analysis the side by side analysis of Star Wars and Wizard of Oz? No. It's fascinating. Star Wars is Wizard of Oz.

Alex Ferrari 41:23

What's to say? It's a hero's journey is basically it's the hero's journey. My favorite is my favorite. My favorite is one of the biggest franchises in movie history Fast and Furious. What's that? That's just Point Break. It's Point Break. It's the literal story instead of surfers their racecar drivers. Right? I mean, essentially the exact same story. anyone listening please go online and look it up. Point Break is the original Fast and Furious.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 41:55

One of my first agents, you know, quote, infamously said this to me, you know, when I asked his advice about you know, what should I What should I be writing? He goes, I don't care. Just make it derivative and make it quick.

Alex Ferrari 42:09

Wow. Wow. All right. So back to the original question avatar. What was about that film specifically that you feel that story? That that caught on? Or like what's going through your system? What is it?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 42:22

Yeah, I think it was, first of all, structurally perfect characters journey. Perfect. You know, it hits you know, undeserved misfortune, orphan wanderer, warrior martyr, you know, on a, on a on a huge canvas. It, it was a cultural event, a cultural event, which you can't find it. Yeah, right. You know, look, you know, it's an imperfect analogy, but you know, you can talk about, you know, the abyss of the abyss. Yeah, I like the Abyss a lot, you know, the character stuff. But, you know, same filmmaker, you know, took us to take us to another world we've never seen before. Also fantastical creatures, and then do a fraction of the business of

Alex Ferrari 43:13

different time to different time periods, different time,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 43:16

but, you know, within 567 years of each other, no, so

Alex Ferrari 43:21

no, it's not. That was in 19. I was in 1990. And the avatar came out in like, 2000. And something This

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 43:27

was 1990. Yeah, cuz

Alex Ferrari 43:29

it was during my time at the video store, so Yes, I remember. There's a, there's a short window of time. 87 to 93 I'm pretty much unstoppable with movie trivia. That's, that's my that's my sweet spot. I can knock it out there

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 43:44

was avatar.

Alex Ferrari 43:46

avatar avatar was if I'm not mistaken, was either it was cuz Titanic was 97 are in 90 See, I was 97 matrix was 99. So avatar was I think 2000. And it was 2007. But 2007 2008 around there are a little less. All right, hold on. While we're while we're speaking, continue speaking and I'll look it up.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 44:16

Anyway. Yeah. So it was just it was it was just a you know, it was such a complete journey into this fantastical world. And, and part of it also was a little bit of a dog and pony show, you know, it's like we've never seen, you know, creatures, you know, in that, like that ever portrayed before. As well as they were

Alex Ferrari 44:39

so that it was 220 and it was 2009. So it's right around there. So it's 2009. So but the thing was with with Avatar, because a lot of people are like, Oh, it's paint by numbers. It's the stories rehashed as Dances with Wolves and all this kind of stuff. But the big thing that made that story go is that keep an eye saw it when I was watching. It was like he hit Every point perfectly Oh, he execute. He basically made the perfect apple pie. Like it like it's a recipe that we all know. But he hit everything perfectly. And then you add on the spectacle and the technology and the event and all that stuff. And then it's an unbeatable combination.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 45:19

Yeah, it doesn't. Things don't have to be, you know, spanking new. Yeah, it's not, you know, any rocket science. You know? No, you know, I mean, it's like, you know, like, you know, yeah, it's always derivative. Nobody's ever, ever claimed that James Cameron was the most brilliant, you know, dialogue writer, you know, in the world. He gets characters really well, he, you know, directs them, you know, effectively, you know, dialogue wise Quentin Tarantino is better than James Cameron. Sure. But Cameron knows how to paint on a very big canvas and and he hits all the beats it's you know, he made it derivative he made a quick you know, it's it's funny. You know, it's interesting seen the movie The Big Short?

Alex Ferrari 46:15

No, of course.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 46:17

This is great. was important, Ramzan remembers, who is the chef? No, was not what was his name? He just died. Very sad.

Alex Ferrari 46:26

I forgot. Yeah, I think I remember I forgot what the for chef is. But yeah, continue.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 46:30

Yeah, but anyway, but he's explaining, you know, tranches of you know, short selling. Right. It says, you know, he goes here to see Oh, here's fish. You know, I bought it, you know, I bought it, you know, for the weekend crowd. But I have some leftover, it didn't sell, so I can't sell it anymore as fresh fish. But I cut it up. And I put it into the stew and now it's a whole brand new thing. Right. So yeah, you know, so derivative storytelling. It's like, yeah, okay, I'm taking I'm taking some old fish, but I'm putting it into a brand new stew, you know, and that's storytelling.

Alex Ferrari 47:03

But that's storytelling from The Epic of Gilgamesh. I mean, it's like,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 47:08

well, that's a larger segment, you know, there are only 36 dramatic situations. Right? So you go, okay. Yeah, that's, that's fine.

Alex Ferrari 47:16

Yeah, and I think and I think a lot of screenwriters and filmmakers in general, they all get caught up with, like, I need to create the brand new thing, I gotta create the new thing and, and I got to create something that's never been written before. And the thing is that everything has been written in one way, shape, or form, all you could do is put a new twist on it or combine certain elements to make it fresh and new. And you look at even if you look at Pulp Fiction, which is arguably one of the more original films created in the in recent history. If you look at it, and you put it up against the hero's journey, and the points that that lays out, it all it hits, but he just what was brilliant about that is he just changed the the timeline, but the thing still hit, which is the genius behind that film. Like it's like, it's it's

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 48:04

my favorite examples from from Pulp Fiction as far as like, how does it follow the hero's journey is, you know, towards the end of, you know, act two, there's a there's the the death and resurrection. Yeah, moment. That was part of it. But it's Vincent Vega gets machine guns. Right, right, in the bathroom. So right. And then the next scene is alive again, because it's just, just the timeline was, you know, was the the conceit of the movie was playing with the timeline.

Alex Ferrari 48:38

And that was the brilliance. But that's the brilliance of that film.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 48:40

That's the brilliance of right. That's what I'm saying. You know, people feel like, Oh, I can't follow the structure. I'll make it formulaic. Because in your formulaic hack, you don't know how to do it better. You know, I'm, hence hence my story can beat up your story. I'm just a little too antagonistic. I should have been nicer.

Alex Ferrari 49:00

So talk like,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 49:03

last night, it was a much nicer person. Yes, yes. Yes.

Unknown Speaker 49:05

Save.

Alex Ferrari 49:09

Just save the cat. Just save the cat. Don't beat up the story. Just save

Unknown Speaker 49:12

the cat.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 49:17

sweet guy, you know.

Alex Ferrari 49:19

So. So we're talking about structure. But I found that a lot of times you I just saw a movie The other day, that the hero. I couldn't identify with him. There wasn't anything really that really interesting about him. And I'm watching this cop drama. And I'm just going and he's a great actor. And it's a and I love him and the cast is fantastic. And the production values great. 21 bridges, the one with with chat chat, chat chat with Black Panther, and I'm watching it and I'm like it's just so good. And like his character had no real depth, there was no history to it. He was just like this. There was some that the screenwriter tried to do something there with his dad and like he's a cop killer, or he's a killer of cop killers, as a cop and all that, but it wasn't anything good. What advice do you have for making you know, for for constructing a good hero? What are some tips?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 50:24

Well, it's you gotta you gotta go back to the sources, you got to look at the hero's journey. You know, it's like, you know, there are a couple of, you know, a couple like super handy, kind of like,

Alex Ferrari 50:36

Swiss Army is like, Swiss Army Knife kind of

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 50:38

army knife. It's like, yeah, you know, it's, I always ask these questions when I'm writing or trying to sort of coach people with writing this, you start off simple, you go, what is your hero wrong about, you know, at the start of the movie, that they're going to become right about, you know, at the end, your heroes got to be the best at something. Right? That's why, you know, you read it, you know, it's sadly like, you read a lot of screenplays or stories, you know, written by people and, you know, the Heroes is like schlub, who's the loser. He's the joke at the office, you can't do anything. Right, you got it, I get it. I know why you're trying to tell that story. But, you know, it's, you're short, you're new, you're not getting the audience in, in, you know, into the character. And, you know, you, you know, if the guys, the guys such a loser, you know, he's not good at anything, you know, then you're not interested. You're not interested? Yeah. What do you what do you what do you want to accomplish? Right? So it's like, you know, what we like, so, you know, and then and then you have to put the hero through the paces of the of the journey, you know, you've got a, you got to make it really clear. You know, by the end of Act One, we know, what's your heroes? You know, I think it was Syd field used to refer to it as like, professional, personal and private, right? professional goal, right? What's his personal goal? What's his private goal, right? So we lose our professional goal is, you know, what? Yeah, is no professional goal is he wants to destroy the Death Star. Right? Right. The personal goal is save the princess private goal is he wants to become a Jedi like his father. Right? And, and the way you can get in the way you think about that is when looking at your hero and your main character, you're saying the professional goal is what's the thing that means the most to the most people that your hero was involved in? Right? Then the personal goal, His goal is, what's the thing that means the most to the hero and a couple of his or her closest, you know, associates, right? allies or friends or family? Right? And then the private goal is what's the thing that means the most of the hero? Right? So it's, it's so it's just sort of a holistic way of looking at your hero's whole life. And, like, going back to your very good question about like, what are some of the big mistakes? You see, you say, sometimes, you know, in a poorly told story, the hero only has a professional goal, right? Or you're the hero is not, you're not, you know, gives up on the private goal to cylinder with a private call becomes insignificant. Right? Because that's how, you know, that's the other problem, you know, that I often see a lot in movies is, you know, we've all seen it. You watch a movie God the movies over and they go on a wait a minute, it's still going on? Oh, it's still going on? Right? It's like, yeah, the people don't know when to finish telling the story. Your movie is over when you've taken that, you know, go back to Star Wars, you know, will Luke destroy the Death Star save the princess and become a Jedi like his father? When you are each of those three questions? Oh, that's when your movies over. Right. So it's, you know, and then the whole the whole film is dedicated to answering those questions. Yes or no. You know, you know, it's like, you know, he goes to moss Isley with Obi Wan. So that's Yes, is by going to my cisely he will be you know, he will be helping to destroy the Death Star, he will be helping to save the princess and he is taking a step closer to being a videojet. I like his father. And but they get stopped in stormtroopers. So now it's all a no, then it's Yes. And so that's why, you know, it's like so then you start playing the reversals, but you got to know the question. Well, you got another question that's driving your hero.

Alex Ferrari 54:27

So much did. Did you did you watch office space?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 54:32

Not much. Did the movie Yeah. Yeah, I saw it a long time ago and then sort of bits and pieces of it more.

Alex Ferrari 54:38

Okay. All right. That was a wonder I was gonna have you kind of break that that carry that mainecare because he was a schlub. But then I was like, as we're talking, I'm thinking, I'm like, what would what is his professional goal? Well, his professional goal want to do this and his personal goal he wanted to get with Jennifer Aniston. And his private goal was to do so he's like, okay, you start thinking about,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 54:56

right what you know, but some movies You know, some movies just don't work. I mean, you know, like, you know, you can't break it down like the guy took the liberty while we were talking about Jennifer Aniston. Looking at how much the movie gross right so the budget was $10 million in the movie gross $10 million. You know so but

Alex Ferrari 55:16

uh, but uh, but it built into this massive follow afterwards.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 55:21

True, but that's not the movie that that's the movie that might judge could make. Yeah, of course, he was coming off of you know, Beavis and Butthead. Right. Yeah, that's not the movie that you necessarily could make.

Alex Ferrari 55:31

I mean, there was also a different time.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 55:33

Also a different time. You can't say it's a different time, every time we talk about a movie that wasn't last week,

Alex Ferrari 55:37

because it's a different time, like our entire industry is so ridiculously different now.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 55:44

And it really goes a different because it's a different,

Alex Ferrari 55:46

it's a different, obviously, different times.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 55:49

But there there there are, we would be remiss if, if I didn't, if I didn't bring up this point, which is that we're really talking about two different types of screenplays here is the screenplay that gets bought. And then the screenplay that gets made. So you know, anybody who is an aspiring writer has to focus on the screenplay that gets bought. Right? Which is very different from the one that gets made. So the corollary to that is, is the screenplay that doesn't get bought, but helps to launch your writing career. Right? So if we, if you really want to get reductive about it, you know, most people, you know, like, you know, you've written the screenplay, What's your goal? Sell your screenplay, or have a writing career? Right, probably having a writing career. Yeah. And selling the screenplay would be part of that. But it's not the exclusive part of it. Right? So. So there's all sorts of radical ideas, I'm gonna go into them in the book a bit, and the whole, you know, the, the smart writers business guide, where it's like, if you Ideally, you want to write a movie that that can get bought. Right, so you got a, you know, you got parts in there that, you know, it's like, there's a, there's a, somebody can read it and feel all there's a star that's, it's perfect for Brad Pitt. Right? Or, you know, like, you can you can see it, you can throw it in the description. Hey, think Brad Pitt, you know, but there's the, from Thelma and Louise days, or, you know, what, however, you want to specifically say, you know who this person is, but then the the other side of it is, you know, is, you might also want to write something so outrageous, and so on. producible I know, it's a weird thing to hear me, you just described himself as a Hollywood hack, you know, say that you're trying to break in, write something wildly, and producible. But make it super memorable. I mean, I remember sitting with a producer. And, and we were talking about this, because I think the meeting was over, I said, Hey, you know, I've just written the book, I'm interested in your thoughts on some of these things. And, you know, and he said, Yeah, you know, we write something and producible it goes, somebody gave me a script once about a dog who wanted to commit suicide. But his owners didn't understand that this dog was depressed and wanted to kill himself. So every time the dog tried to do something, like it was laying out, you're like, grabbing the toaster, and trying to jump into the bathtub with it. The owners would be like, Oh, boy, are you hungry? Let me get you some food. Yeah, like, they. It's brilliant. It's brilliant. I promise you if we have a conversation, 20 years from now, and I hope you do as I'm enjoying speaking 20 years from now and say, hey, what was that? Um, producible movie I talked about wanting to make that movie. But you don't you you but it's, you know, I never knew the name of the writer, I'm sure the producer wherever he is. Mo can still tell you the name of the writer, you know, or at least remembers the screenplay. So it makes you memorable. It helps launch a career. I'd love to find that. Oh, that was oh my god, I would so watch that movie.

Alex Ferrari 59:07

Can you imagine if it was? Imagine if it was a Pixar Animation? Ah.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 59:16

Yeah, so so there is a certain aspect of the business about new rights, something

Alex Ferrari 59:21

that's really so it's really yeah, it's really a great it's a really great idea. And I've read I've actually read scripts from screenwriters, who then got deals because of it was basically a writing sample. I read I read a script about it was a mash up between Alice in Wonderland and Sherlock Holmes. And it was just mash up and I read the script. I'm like, this is completely unpredictable, but it's very memorable. Really good writing tight. An agent of mine gave it to me one day to read I was like, Oh, this is great. I can't wait. No one's gonna make this. And it was right before Sherlock Holmes got released, and a TV show and all that stuff. So it was still a little early, but it's a little out there for the mainstream. But it's a great but it's a great. It's a. It's a great, it's a great, memorable piece. Now you do talk about one thing in your book that I wanted to bring up before we before we go is what is the unity of opposites?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:00:13

the unity of opposites. I love the unity of opposites. It's my favorite thing in the whole world. Yes, it's this idea that it's and I didn't even invent it. I wish I did. But it's this principle that that characters are connected at some thematic level. And, and they they represent opposite sides of a moral or thematic argument. So yeah, so it ties very cleanly into theme. I will go back to Star Wars, I guess. It's like imagine like a, you know, a wheel, right? And you put Luke as the hero in the center of the wheel. Right? The villain is actually not Darth Vader in that piece. It's really, you know, Peter Cushing's character, you know, Vader works for him. So he's, he's the big bad guy. Right? So, you know, and then you you create these characters that go around Luke. Right? So Luke in the villain, so the hero in the villain are connected on this thematic line. In first Star Wars. The theme is what's more powerful faith or science, faith or technology? Right? Because that's this whole thing shut off the targeting computer, Luke, ready doesn't distract. Right? So that's the theme, right? What's more powerful faith or technology? Right? Then you have the unity of opposites. So you have to do so you have your six characters circling Luke, right? You have at the top, you have Obi Wan and Darth Vader. Right? they're connected? Because they're both old jet eyes. Yeah, they've trained together, they understand the power of the force, right? But they're opposites. Right? Once the darker ones the light. So you know, and if you ask them, what's more powerful faith or technology, if you asked, If you asked Obi Wan, what's more powerful, he'd say fair, vs. Darth, he'll say, well, fates really important, but technology is what's keeping me alive. And you know, the Death Stars is big ball of technology, not big ball of faith. And that's where he's currently working. Right? You know, so it's like, so he's representing technology. So So Lucas? Oh, cheese, I wonder what's more powerful faith or technology? He taught me Oh, he understands from Darth and he understands from Obi Wan. There are two perspectives, right? And on the other, then, you know, on this side of Luke, you have Princess Leia, and you have Han Solo. So these are young, you know, self actualized people, right? So if you ask Leah, what's more powerful faith or technology? She'd go with faith, right? Trust, you know, help us Obi Wan, you're our only hope. Right? She has faith that you know that people will do the right thing. You ask consolo, what's more powerful faith or technology? He's going to say technology, you know, hokey religions are no match for a blaster kid. Right? technology. Then at the bottom, you've got the last two of your heroes main characters, and that's c threepio and artoo D to write. Both of them are, you know, are big chunks of technology. Right? But you ask, see, threepio what's more important, you know, what's more powerful faith or technology? He'll tell you technology, right? He has no faith, right? versus our two D two, which you know, is going on missions. And you know, he's got to help the princess you know, he's, you know, he's the best friend character. Right. So, so the unity of opposites. So these, you have two robots, you know, are connected the, the unity, but they're opposites. You have the two self actualized young people, you know, older than Luke, but younger than Obi Wan and Darth, you know, opposites. But you know, there's a unity to them. And then you have Obi Wan and Darth opposites. But there's a unity to them. And it's all about the theme. So the thing that the thing I love going back again, to the question of you know, one of the mistakes I see I say, you know, in screenplays, the themes are muddy. You know, you don't know what's what's your story really about? What's the argument? You know that? What's the thematic argument that the villain is making? What's the magic question the hero was asking? What's the thematic synthesis? What does the hero learn about the theme by the end? Right? So So unity of opposites is a cool way of, of identifying your characters, but also tying it to the theme would you know which which becomes super important?

Alex Ferrari 1:04:46

Now I'm going to ask you a few questions. I asked all of my guests. What advice would you give a screenwriter wanting to break into the business today?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:04:54

Don't write a screenplay. Okay. Okay. Yeah, TV. TV, write a an original pilot, don't write a spec episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. Don't write a spec episode of 911. Right? Because you're never gonna, you're never going to match what? You know. 911, you know, has, you know, can afford the best writers, you know, in the business, and they all sit around together and they bounce ideas off each other and they distill out an idea. So you versus the entire writing of Yeah, the room at 911 you're never going to write a script even close, right? And if you do, they're never going to buy it. And and if they don't, if they really impressed me, maybe you get a job, they average and I'm going to get a job elsewhere because it's 911. So if you don't get your 911 job, you got nothing, right? You write an original pilot one hour drama, right? You write a an original pilot it, they have nothing to compare it to. So already, you know, it's not like well, it's not as good as our 911 script is not as good as our original pilot. But still it's an original pilot and it's really good. People will pay attention to it. You might accidentally sell the damn thing right because if it's any good and it's a solid writing sample, right you know so it's and there's so much you know, so many more opportunities in television and it keeps growing I mean number of original movies that get made I mean here so go to Internet Movie Database right now go to the homepage. Let's see films in development Thor it's a NO SEQUEL Jurassic World three sequel Fast and Furious 10 Raina in the last dragon I know what that is. Oh, DreamWorks must be based on material animations. Animation, Bad Boys for sequel? You know, pre production Doctor Strange. Guardians of the Galaxy last tool is an original Shang Chi legend is something Mission Impossible seven. You know, it's like, you know, in production minions, Suicide Squad, Batman matrix for avatar.

Unknown Speaker 1:07:03

They're all

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:07:05

Yeah, right. You know, this is all material you can never get your hands on, you can't get access to but you come up with an original thing. All of my point was via movies or going for the big 10 polls and just the budgets have gotten so big. The TV you can come up with something kind of new and interesting and different, you know, get in

Alex Ferrari 1:07:23

and get in have an I have a fighting chance, I have a fighting chance.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:07:26

And you can actually in TV writing you actually have a trajectory, you know, I can get in I will start you know, my my, my personal assistant on my last TV show stitchers guy named Matt Kane. You know, he worked for a season as my personal Savior for two seasons as my personal assistant, you know, produced production producers assistant, second season I said, Hey, you know, you're really good writer. Let's let's work on it. Why don't you write a script with me? You know, so I got him script writing. On the second season. He worked with me. He just texted me last night that he's officially in development with Netflix on an original pilot that he wrote, right? That's a trajectory. Right? You haven't TV? It's a trajectory film. It's It's It's a never ending series of winning the lottery.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:17

Right? That's a really great way of putting

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:08:19

up TV is such a better business. And to be candid, I think the best writing is on television. It's not in films anymore. Right? Yeah, you know, it's it's the people who knows these things have said that if you didn't like whatever that Metacritic kind of algorithm that you have to look at to say oh, here's a good TV show by by all objective standards, this is considered a quality television show that there are so many of those shows that have crossed that threshold into being a quality show that there are there are no longer is the first time in history. There's there are no there aren't enough hours if you did nothing including sleeping and pooping and you did nothing but watch quality television shows that a objectively considered quality you could watch them more and more coming out every week.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:15

Oh no, it's it's awesome. That's

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:09:17

my best writing is television. So you want to break into the business. Don't write screenplays. Write a one hour drama original, not a not a spec. You know, 911 or Game of Thrones?

Alex Ferrari 1:09:28

Very, very great advice. What is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film business or in life?

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:09:36

Wow, the lesson that took me the longest to learn is that I don't know everything. I'm still learning that because I have a problem that I actually do think I know everything.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:50

We are in the film business. So this does.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:09:52

I can't possibly know everything yet. I still think I do. So y'all I'm sorry. grappling with that, and I know I know, I don't know everything and then I'm being a little bit tongue in cheek. But you know, but it's, I think to try to make it make me sound like less of a moron and more thoughtful about it. You create something brand new, right? You a script, the pilot, whatever. You have to be willing to believe. I think that nobody understands it the way you do. Right? And, but you also have to be willing to think that people can help it. And the lessons try to figure out, what do I get the help that I need? versus how much do I hold on to what I think it is? And it's, it's a particularly challenging bit of math. If you become a showrunner, right, because as a showrunner, you're responsible for everything. And I know talking about television again, but but the idea is that as soon as you start, you know, as soon as you start making changes that you don't agree with, right, just based on you know, some enemy, some, it's, there's politics involved in studio notes, it's, you know, notes for your partners. But as soon as you start making changes that you don't feel, right, then you become useless to the entire endeavor. Because, you know, you don't know, you know, if you pitch me an idea for an episode of our show that we're working on, and I'm show runner to suicide

Alex Ferrari 1:11:31

dog by about bow suicidal,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:11:33

exactly, right, right up between idea I can react, instinctively go, Yeah, I don't know that that's not sitting well with me, you know, wherever this pilot, or this TV show came from, that idea is not living in that same space, I could try to elucidate it over let's just reject it and come up with something else. So that's me thinking, I know everything and rejecting help of good ideas coming in. So you have to be able to figure it out. It's kind of parse that calculation is how much do you defend your material? Like it's your own child? versus how much are you willing to look at? And go? Yeah, my kid could use a little therapy.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:10

Fair enough. And three of you.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:12:12

That's the hardest lesson, I think, for me personally,

Alex Ferrari 1:12:15

and three of your favorite films of all time.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:12:18

Ooh, they're their favorites for all sorts of different reasons. Star Wars, because I saw it and said, Oh, my God, you know, I was 17. Like, it was just such a complete journey and trip. That was pretty amazing. 2001 Yeah. Because I, I saw it in my teens. And I was like, wow, that's, you know, film can tell a bizarre is linear and nonlinear.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:43

It's Kubrick. It's just too

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:12:45

quick. Right? Yeah. And, and then probably, you know, for historical reasons, Citizen Kane, because it showed, you know, it showed what the what you could do if, you know if you didn't listen to anybody. You just ran with it. And you know, then the movie almost killed him.

Alex Ferrari 1:13:06

Very much.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:13:06

So it Citizen Kane. So some movies I like for like, you know, Mike Lee I like it, because they really touched me. And there's all sorts of movies, you know?

Unknown Speaker 1:13:17

Right? You know,

Alex Ferrari 1:13:18

like so many are then where can people find you your work and in your book.

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:13:25

The book is on Amazon calm. And my story can be a pure story. I do have a poorly used website, which is my story can be up your story calm. But, but if we have a moment or two, I'll make a plug for a brand new venture that I'm involved in that were started a company. And we put out our first product called writers room Pro, which is taking escar cork boards and the handwritten whiteboards that are commonly used in the writers room and saying This is nuts that this hasn't shifted over to a digital equivalent. I know why it hasn't because the price of big monitors used to be too expensive. It's not anymore. So the time is now ripe for for rhizomes to know like editing switched over from you know, from film and trim bins with avid and, and cameras switched over from film cameras to to digital cameras, it's time for the writers room to switch to a much more secure and much more robust solution. So that's the new venture so it's a check it out at the writers room proz.com. And it's it's really designed for professionals but we have a lot of individual writers who using the whole system and it's not a story system, right? It's not we're not trying to teach you here's how you do a plot out a television show. It's really it's just if you could put it up on a board with index cards, but if you wanted to make it certain And you can output everything and import it into Word and final draft and stop it.

Alex Ferrari 1:15:05

And the madness. stop the madness madness,

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:15:08

right. So that's that's the thing I'm kind of most excited about these days, you know, it's very, very into my TV business. So writers room cro.com.

Alex Ferrari 1:15:17

I'll put that all in the shownotes. Jeff, thank you so much for being on the show. It's been an absolute pleasure talking to you. Thank you. It

Jeffrey Alan Schechter 1:15:22

It was so great talking to you too.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

LINKS

- Jeffrey Alan Schechter – Official Site

- Jeffrey Alan Schechter – IMDB

- Writer’s Room Pro – Software

- My Story Can Beat Up Your Story: Ten Ways to Toughen Up Your Screenplay from Opening Hook to Knockout Punch

SPONSORS

- Backstage – Book your next job and grow your professional network (USE THE CODE: INDIE80)

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Filmmaking or Screenwriting Audiobook