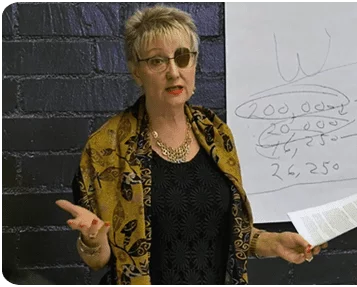

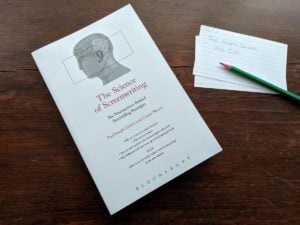

Today’s guest is screenwriter Paul Gulino. Paul is the author of The Science of Screenwriting: The Neuroscience Behind Storytelling Strategies.

Paul believes in Hitchcock’s adage that “films are made on paper.” Although students may obsess about a film’s look, all of the visual elements, he says, function to enhance the story. And that, ultimately, comes from the mind of the screenwriter.

In spite of the fact that there seems to be a screenwriter behind every corner (in California, at least), screenwriting is something of a lost art, Gulino maintains, having seen hundreds of flat screenplays as a story analyst for Showtime Entertainment.

Honing his own skills through writing for the theater and practicing the craft as taught by Frank Daniel and Milos Forman, Gulino secured an agent with William Morris on the basis of his thesis script. With that “real world” confirmation in hand, Gulino went on to write and see produced features, plays and comedy sketches.

Screenwriting, he says, isn’t a craft you can learn from a book.

“The best way is to learn from someone who knows the craft, so you can see how theories can be applied to your own work.”

There must be something to that. Or at least it’s worked for screenwriter Paul Gulino.

Enjoy my conversation with Paul Gulino.

Alex Ferrari 0:36

I'd like to welcome to the show Paul Gulino. How you doing my friend?

Paul Gulino 3:12

Oh, I'm doing much better now that we've started live. Thank you for being part of my world.

Alex Ferrari 3:20

Yeah, I appreciate it. Like I told you, when we were off air, I always love bringing different voices and different ideas on the screenwriting process, because you just never know what's going to connect with that individual screenwriter out there where they might would like one person or they might like the other person, or this book really talks to them, or that idea really talks them. So I always love to bring new ideas on. And when I read about your ideas and your approaches, I was like, well, I gotta get Paul on the show. So I'm so glad. I'm so glad you're on. So first of all, how did you get started in the business?

Paul Gulino 3:51

I started with a super eight camera when I was 10 years old, you know, dad to break camera and making a movie with our dog, the family dog and then graduating to Super eight sound and then finding out one day that there was such a thing as the film classes taught at university but I was like, really, and I studied with Frank Daniele at Columbia University. And as I said before he was the he's have a lot of very successful students is a was unique teacher is stable would include Milos foreman would be recognizable David. David Lynch was another one Terrence Malick. Martin breasts was one of his students at the American Film Institute. He's on top. So there were a lot he had. He was the founding director of the American Film Institute, and he brought his pedagogy from Czechoslovakia to the United States through that, and in turn, his pedagogy came from studying American Cinema in Czechoslovakia, and basically watching movies over and over and over again, because you could do that for one price, sitting in the theater and then applying Western dramatic theory to understanding how how movies work. And then his approach to teaching was sort of like working with you as a collaborator on your script, while smuggling theory in so you have a broader picture of how, what your choices are basically making you aware of what your choices are when you're telling a story, so and so that's how I got my start. After I went to film school with Frank, I was doing the thing with writing and was in New York City. So I was working on stage plays, and trying to get things release in front of an audience and then moved to LA in 89. And then, was able to get an agent and he was able to sell a spec script and and got that made, I like to say the screenplay was loosely based on a real story. And the movie that resulted was loosely based on my screenplay. And another film made a few years later, and I've been working as a consultant working, worked on an Animated Feature Animation on a project that could not get made, but it was a it was a great experience, you know, one of these things where they spent $30 million on it, and then decided I was the sixth writer out of about eight writing teams on the project. Fair enough.

Alex Ferrari 6:48

So when you came, so when you came to LA, though, it was during the whole spekboom time, isn't it? It was the time where spec rise spec scripts were like, everybody was making a million here, 2 million there. I mean, the whole Shane Black Joe Astor house era of spec scripts, it was that time, right.

Paul Gulino 7:07

Yeah, that was basically the 80s was the discovery that there's such thing as writing a screenplay. And that you can that that's a viable option, and that Hollywood resolve into this thing back then. Yeah, there were there have been periods when they work. And then they weren't. And then they were, you know, there was a boom in this an interest in screenwriting, or what they called, at the time photoplay writing back in the 19 teens. So you look back there, you'll find about, I believe there's about 60 titles on how to write a photo play. And the public was very interested in this. And there were manuals, how to write a photo play, and because they were taking from the outsiders at that time, and then you have this drought for many years, because Hollywood became sort of a closed shop, Film School of that time, and then starting for variety reasons. In the 70s, things fell apart, and it opened up and new voices were heard, and that's when screenwriting was sort of rediscovered, and then starting in 79, you have subfields book come out. And then the boom in screenwriting books, pedagogy and interest in it begins there. And so when I was in film school there actually, my path is my frame of reference is very different because there were no manuals at the time, I was learning from somebody who is from a master teacher, and there were books on playwriting. Certainly there were plenty of those. But it was it was something being rediscovered at the time. And what how do you put this stuff together?

Alex Ferrari 8:52

So you you've been teaching for many years now. So you've had a lot of students you see, you've probably read a handful of screenplays, just a handful in the course of your of your time teaching. What is the biggest mistake you see first time screenwriters make?

Paul Gulino 9:08

That's an interesting question. Because my perspective is a little strange in that I I'll train them initially. So like they're not writing a feature script that nobody hands me a feature script right away and it has the effect that they have to go through. Kind of like Etudes you know, how musicians have scaled cetera? Well, we have writing Etudes, you know, they're going to exercise different writing muscles and then they build up to a feature and then then start working with them on that. So said once I've consulted on where I get a full line, are you hearing a hammering it somewhere?

Alex Ferrari 9:47

That's okay.

Paul Gulino 9:47

Okay. We got sound engineers, you know, that's it. I'll get rid of that. The ones that I see nowadays what I can notice is In a way, they're overthought. Like there's encrusted with all these different, you know, they read a lot of books on it, and they want to do it right. And I'll have stories that are promising. And then, but I see they're jamming it into some idea. And then they're really proud of the fact that I, okay, I have the second twist here, see, see, I got it here. And this is here. And so there is often a departure from between conflict between what their story is and how they're executing. So for example, I was doing a romantic, working with someone working on a romantic comedy recently, and this person had a woman main character, and she's going after them, she's with the wrong guy, you know, she's with the wrong guy, and the right guy is right out there. So enter the second act. He's got this, all is lost moment, or dark night of the soul. And that moment consisted of her finding out that the guy that she's with is all wrong for her. He's not only not right for her, but he's stealing and he's cheating. He's, I don't know why he's probably got, you know, murdering puppies somewhere. I wasn't that bad. But it was like she makes discoveries. And why? Because you're supposed to have this happen at the end of the second act. And I said, Well, wait a minute. She doesn't belong to this guy. So maybe the end of the second act is she gets some audio. But it sounds like from what your material, the worst possibility would be that she lines up with the wrong guy. So the worst thing that could happen is he proposes to her and she accepts it. Now we have a third act tension, which is going to be is she going to realize in time before the wet hick send the right guy right there, you see that the landscape is, I like to say all all truth in screenwriting is local, you know, depends always. Yes, you could have a desperate moment at the end of the second act. And then what the terrain of the story is you're working on. And so I've run into that. I don't know how helpful that is. The The thing was, the other thing I noticed that I have to work with students on is his dialogue, and the mistakes that they make, and it's certainly mistake I made. And it's a mistake that people starting out make. And I can see that it's not about overall feature screenplays, it happens in short films. So I can tell you what they come with is what I call q&a dialogue, Question and Answer dialogue. Yeah, character enters the room and says, How are you today? And the person says, that I didn't sleep much last night. How about you? Well, I slept pretty well. But I am thinking of going to the store. Would you like to go to the store? I think I might go to the store. But you know that one question, one person questions, everyone answers, and it's emotionally neutral. So we work I work with them on how to overcome that that problem, how to understand how characters interact, and how you can avoid that sort of behavior in your scripts, and then make them readable. So that's, that's a mistake that I see. And that's what people do. takes a while.

Alex Ferrari 13:23

I realized when I was first writing screenplays I'm by by no stretch a master screenwriter by any stretch. But when I first started writing, I did everything a lot of the things that you're saying right there, I did, because I was I've read so many books, and I read so much technique that I was like, on page, this, this has to happen on this line. So I would like jam it in there. Regardless if it meant it was correct or not correct. And I would literally conform the story around. Absolutely having to hit this specific point. And I found it and from my own experience, that it is just it's insecurity. You know, it's an insecurity of not not feeling comfortable with the craft enough to be able to just let it let me do what I need to do to tell the story like, you know, with with these master screenwriters out there, even master filmmakers that they take their time and they don't, you know, they don't have to hit certain things. Yes, they're going to hit probably the three act structure or something like Raiders of the Lost Ark, which I think has a five act structure if I'm not mistaken. You know, those kind of things. They'll hit those points in good time. And as long as it works within the stories that makes sense.

Paul Gulino 14:38

Yeah, it's it's, it's to me it's because I was trained before a lot of theories came out other than Aristotle and sure poetics other more traditional drama. The way I was trained, if you look at what the function and what then out from the very first meeting in first class, it's about connection, as opposed to expression. If it when, take a step back and ask yourself, when you go to a film school, when you take a writing class, what is it, you're actually learning, you're now learning how to be creative. That's not something that can really be taught that we know of yet. And you can create circumstances by which people can maybe be more creative, but it's not well understood. And, you know, it's hard to model with computers to get computers to be creative. So we don't do that we don't teach you the creative process. What we do teach you that what we have learned a lot about, over the last several 1000 years, is we've learned about audiences. And, and we can, if you know that your job is to connect with an audience, we can teach you about audiences. Now, I don't mean like, a particular demographic, I mean, a general person, a normal human being, how do people respond to material? And so when you think about how a story is structured, a term that's used a lot, by structure, I guess I would mean, the arrangement of the pieces, the pieces being the scenes, and information. You You can see that strategy, you know, three, x five, x, whatever, as a kind of subset of the bigger question of how do I grab them? And how do I keep them? How do you grab an audience? And how do you keep that up. And if you know how, the tools, if you have the tools to do that, you can use it in a variety of very exciting, interesting ways. And you can pivot between the feature film and the stage play series, you know, streaming series, because you know how that's done, you know, how to get in people's heads. And that's one of the things that fascinates me about this, why I wrote that the second book with county shares a psychology, like a college professor, it's how to film get into people's heads. And how can I get how can you teach people how to get into people's heads and manipulate them? And one of the things I like to do when I'm lecturing is, I'll show them like a short film that I like, like a four minute movie, and then I'll stop it, like, with about 30 seconds left in and say, Sorry, we got to move on. I'm sorry, we you know, and this movie has achieved something. It's got them wondering what's happening next. And when I do that, you hear the groans I say, what's wrong? I'm, okay, I showed you most of the movie, why do you have to see the rest, you know, and I, I just showed this, these images up here in sound, and it went out into the audience, and it worked them over, and it manipulated them. And now they're kids, because they want to see the end of this. And that's like, amazing. And I love that fact, and I love learning how to do that. And then teaching people how that can be done. And so when we talk about three act structure, or do you need it, or do you not need it the way it's about how you define, if you define them by function, what is the function of the Act? Well, if the function is to create what we call dramatic tension, which is who will the boy get the girl or the boy get the boy and let's not generalize this, we can, in the modern age, we can we will, the LGBTQ person gets the one that they like, yes. Well, that person get that person. Okay. That's the question, okay. And we, if we connect with that character, we're going to be tilted into the future, we're going to be wondering whether they're going to get that person. And then, so you wind up in drama, it's called the main dramatic question. Okay.

Will will the person get the other person? And the question question has three parts, you post it, you deliberate, you answer, you don't need more, and you can't have less. And so if you want to do dramatic tension as your main tool for keeping the audience interested in your movie, you don't have a choice. I mean, if the character if the audience is watching something, and they don't know why the character is doing what they're doing, then they're not going to be in suspense about whether they're going to get what they want. It's not gonna work. So therefore, you need to pose that question in the audience's mind. And then the third act as you answer the question, I'm sorry to interrupt you. So

Alex Ferrari 19:40

no, no. Because you wrote this book, which is called the neuroscience of screenwriting, which is is amazing. It's amazing. I love studying neuroscience. It's a hobby of mine as crazy as that sounds. I love studying neuroscience. And I want to ask you, what is it about the human mind That that example that you said in your class when you cut them off? What is it in our brains? That is this need to know what happens this? Absolutely, because you go on the ride and a good story, a good movie, a good book will take you down this road. And if someone ruins the ending for me, that's still worse if you get a spoiler out, or you ruin the movie for them before they ever get to watch it or ruin the book or anything like that. There is anger, there is like pure anger. What is it on a on a neuroscience level? What are the connection? What are the synapses in your mind that are coming I mean, this is just programming over 1000s and 1000s of years, 10s of 1000s of years of telling stories around the campfire where now we're just if we don't hear the end of that story, we could die. Because that was the original. Originally the story was like there was a tiger who ate the child. And if you go around this corner, what corner? What corner, what corner, we need to go around? I'm sorry, I can't tell you the corner. And now you're dead. So I don't know, is that something? I'm just throwing that out? out there?

Paul Gulino 21:09

What do you think? Well, that's there's, there's one theory, which is a little bit experimental. It hasn't been confirmed yet. So we didn't actually put it in the book. But there's a theory of mirror neurons that Connie talked about that. This idea that when you watch somebody eat a chocolate pie, the very same neurons that are happening in their brain, if you like chocolate, you know, are firing in yours. So you connect with it in that way.

Alex Ferrari 21:37

That's, that's basically advertising.

Paul Gulino 21:42

And, by the way, I make a great chocolate meringue pie, you know, so just because it's important to me, but so, but that's one there, but it hasn't been confirmed. But the best, the best argument that I've heard about, okay, why do we read stories? Why do we watch stories? It's because it's universal, you kind of look for, what's the adaptation and evolution, because in evolution and human existence in any kind of life form, any activity takes energy, and you're going to have to eat or consume things in order to have enough energy to do that thing. And you don't want to waste energy, you could start Okay, or not efficient. If you could spend your time hunting rather than doing something else, you're wasting your time and you're reducing your chances for survival. Well, so why are what stories must play some role in survival? And a good argument comes, there's a book called the storytelling animal by Jonathan gottschall. And his argument is this that we mentioned in the book, it's that it's like learning, it's a learning, it's a way of learning about life without being in danger that you are, it's a rehearsal for life. And it is a learning thing. You like you just said, you tell a story about this Tiger that's over there. And you don't tell people? What's the lesson learned? Then? It's, it's, it's not. It's frustrating. And this process by which we become involved in the storytelling, there's other theories about that. It's it has to do with how we, in terms of connecting with main characters, let's say, Now, why do we do? Well, there is a process by which some would argue that morals and society are created, which is one theory is called blurring, that you'll literally you'll blur and become another person. Like the example, the one the theorists gave was, this lady is thinking of killing his neighbor, her neighbor. Okay. And then, before she does that, she imagined what it would be like to be that neighbor. And then for a moment, she mentioned the pain that she would cause by doing that, and then they're blurred, their identities blur, and then she decides as a result, I better not do it, because I don't, I don't want them to feel the pain that I've paid to feel. Okay. So that's a theory of how we connect with people. And that's deployed by storytellers. When we tell a story. When we connect with a person on screen. We literally lose ourselves. I mean, I know you've had this experience, of course that yes, yeah. You You're watching a movie I've had in a movie theater where the power went out, you know, where am I I'm, I'm in a movie theater. It's new and I thought it was nighttime because the movie, you get lost in it. It's

Alex Ferrari 24:35

very mad. It's such a magical thing. It really when it's a good story in a good movie or a good book. You're not there you are in the story you are, everything else just shuts down because you were we're literally sitting in a dark room for two hours. Looking at some images flicker and some sound play. It's it's fairly a magical experience in the moment

Paul Gulino 25:01

Right, there's this thing called the willing suspension of disbelief that you're willing to do that. Okay? Well, gosh, I'll argue that it's not willing, you can't help it. If I start telling a story, okay, there was a ship on the sea and the sea salt was blowing. And you know, the waves were coming in the clouds appeared on the horizon. And there was, you're there already, you can't stop feeling those things. And hearing and imagining

Alex Ferrari 25:28

is, is the equivalent of saying, Don't think of the pink elephant.

Unknown Speaker 25:32

It could be

Alex Ferrari 25:34

whatever you do, don't think of a pink elephant right now. And you're you can't, you can't stop it. Now everyone who's listening right now is thinking of a pink elephant. But I told them don't think about it. So very soon, when you were telling that story, I was already I was already going in my head. And connecting to the experiences of when I was on the Odyssey on a boat, or when I was on and I could smell the ocean. I was already I was already going real quick. And I wasn't even exerting any energy to do it.

Paul Gulino 26:02

Yeah, it, it comes naturally to us because it helps us another psychologist. Let me get I want to make sure I get the name, Keith outlays. He has an article called the flight simulator of life, that stories are the equivalent of a flight simulator. For an airline pilot, you're on a flight simulator. So when you crash, you don't die. A movie, your you become that other person in the movie in the story in a film and the TV series. And they go through all kinds of danger, and they learn lessons. And guess what you got to learn the lesson that they learned but you didn't have to die. You've got to learn it. So even a tragedy where the character doesn't survive. You learn from you know, you've learned don't do that.

Alex Ferrari 26:55

Now, isn't it interesting because as of this recording, the Joker came out in theaters last week. And it is causing all sorts of commotion people are walking out of the theater, people are loving the movie. It is it is a very diverse, a film that divert not diversity. What's the word divisive film, right? Because and I haven't seen it yet I have. I have my tickets because I either. I want to see it too. But the thing which I bring it up for this conversation is that you are following a villain. You're watching a person go from being maybe a damaged human being into a full blown villain, arguably a psychotic maniac, who is arguably one of the you know, greatest villains ever created in the scope of movies and possibly in comic book lore as well. So people have a problem with that, because you're now attaching yourself to a villain in such a deep, dark way that it is bothering people. And I can't remember a movie. I mean, taxi driver would probably be the closest thing like when you watch taxi driver, there's a lot of people who just can't deal with it because you're you're Travis Brickell, I mean your,

Paul Gulino 28:19

your work that I do that

Alex Ferrari 28:21

you're in there, there is nothing else you can attach yourself to and the filmmaker and the storyteller and the screenwriter. Dave, you're Travis and you're going through and you're he's, he's who he is. So people that's why films like that have such a diverse, divisive, a feeling. And in today's world, you don't get those kind of films. So I'm excited to watch the Joker in these put up by Rudy.

Paul Gulino 28:45

Yeah, that that'll that'll be very interesting. The usually, like there have been successful movies. And one reason one word I discouraged by students from using that's popular is when they talk about the main character is hero. And I understand like the hero's journey, they don't necessarily mean hero, but when you say some of the hero, he got a The, the impression you get the connotation is, oh, someone who's hero, they do heroic things, and they're strong, and they're attractive and all that. But we don't learn from those kinds of people we learn from people who got problems and, and trends that transgression, they do the wrong thing. But you can still you can have a character who's a, let's say, a man who has an affair with a married woman and decides to murder her husband so he can get money. And we'll go with it. Because you know, Double Indemnity, that that works, but there isn't enough there for us to connect with so that we're okay with going for the ride even though it was controversial at the time. Yeah. And there was questions about who couldn't get naked. For a long time, and then there was this sense that people do learn from movies, and therefore we can't have bad people as main characters, unless they're really punished. And I don't know if you're aware of this, but they wrote and shot an extra sequence in that movie that they cut out. And that extra sequence was, you remember the film very clearly.

Alex Ferrari 30:20

Very clear. I saw years ago probably films

Paul Gulino 30:22

years ago. Okay. Well, the last scene is spoiler alert, but it doesn't matter. It's so

Alex Ferrari 30:29

if it's over, if it's over 5060 years old, it's not a spoiler alert anymore. It's the

Paul Gulino 30:36

I can't get to the Statue of Liberty Statue of Liberty. Exactly. So this what happens at the end is he actually it's wrapped around with the beginning of the pack that begins with actually a flood that begins of the present. And the whole thing is a flashback with the guy narrating. And in the end, he stumbles and falls in the office, and that's where it ends, you know, and he's with his buddy, who suspected him and had to, you know, ultimately turn him in. But that was, that's where they ended it. But the next sequence that they didn't shoot involved, Fred MacMurray is execution, he goes to the electric chair. It was an extensive, elaborate sequence. And keys, his best friend is sitting in the audience, you know, watching his best friend being put to death for his crime. They realized it was a little too much. So they they cut that out, but you could see how conscious they were making sure that we don't connect with, we don't learn that it's okay to kill people from this movie. Another picture that I like to cite is one that's made the main character committed statutory rape, and is in jail for fighting, fish fighting and people having you know, assaults. And also he's a lazy bum and doesn't want to do any work. That's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. That's, that's, you know, McMath mcmurphy. A movie. Yeah. But so you've got this flawed character in his own way. And the way it is, is tragic flaw is a good thing. He has humanity. You know, that's how the movies really twist things around. But we, our first impression of them is, and that's something called the primacy effect first impression, the first time you see him, he's, he's whooping it up for joy. And then he's going around trying to talk to people and helping him with play cards. So your first impression is, he's a good guy. And then you learn a little bit more about him. And then you find out what kind of person he is, but but his behavior is at odds with that. So I don't like didn't censor themselves from having interesting flawed characters. Now, the Joker, I haven't seen. The reason for diverse opinions is something else that we talked a little bit about in the book, it just has to do with, of course, what we bring the movies, and we do bring on life experiences. We write and so different movies are going to affect people in different ways. And I tell my students, you know, when I pick movies that I show that I analyze that it's taken for three reasons. One is I feel have to feel that they work, because I can't show you a movie that why and how it works if I don't think it work. The second is it has to be rich in the in the craftsmanship. So I can point out different things that the writer and the storytellers are doing, that they can learn. And the third thing I tell them is the luck of the draw, I got to love it. And that's just me. And if they're out of luck, as the guy in the next room, he's going to show a different set of movies. And that just has to do with what resonates with me in particular. And there is a concept in constructivist psychology called the schema. A schema is a is a conceptual framework by which we understand the world. It's a shorthand way of understanding things. You it kind of borders with object recognition, but it's like constructivist psychology, which plays a role in how we understand movies, and which I think if you understand that you can have fun is the premise of that the argument is that our experience of the world, our experience of life, is not largely knowledge based. It's

based on inference, because our brains are powerful enough to process everything that we're seeing all around us, you know, of course, of course, right? So an example would be if you see a curb on a street, you know, a curb. The first time you're going to look at it, you're going to check it out, when you're two or something and you're going to navigate it. But once you store it, it's called that's called bottom up processing. You see it, it goes up in your brain. Then after that, it becomes top down processing where you see a curb, you compare it to their memory of how curbs work, and then you assume it's like any other So you just walk over, you don't measure each time you walk over, that wouldn't be efficient. So we take, we have those shortcuts. And what happens is that sometimes we're wrong. Sometimes that curve isn't what we thought it was. It's a different curve. So we thought we thought so. So when we that, we'll get back to that in a second how that plays a role in screenwriting, but in terms of how we perceive things, we do bring that top down processing to the world because we've all had slightly different experiences. So that going back to Cuckoo's Nest, there's a scene in which a nurse ratchet the first time she does this group therapy, and it's terrible. She's it's just everybody's at each other's throats. And she's sitting there impassively at the end, okay. And I started there, and I asked my students, what do you think's going on with her, and I got different reactions. The first one said that she was a sadist. And she's happy that they fell apart. Another one said that she thought this person had regret that they weren't healthier. Another one was, you know, there was a variety of these things. And no one's right. It's just, they're bringing their stuff. So the Joker will be an interesting one, to look at what we identify with,

Alex Ferrari 36:17

I always I always tell people that, from my studies in neuroscience, that many of the things that stop us from specifically being like screenwriters, or being artists in general is by the associations of things that happened to us in the past, where you either associate failure and your brain tells you, you're basically the brain needs to keep you in this nice safe box, you're in a safe zone, that safe zone is where you go, and you only go up to the edge of that safe zone, because outside of that zone is unknown, and whatever is unknown, is potentially deadly, because that's our how our, you know, our alligator brain or reptilian part of our brain works. So that's why it's so difficult for people to lose weight, because their safe zone is being where they're at, or I can't write a screenplay, I'm just gonna do a short first. And then they slowly build up the courage to like, I'm gonna do a screenplay. And then, and if it's not really good, or if it's, someone beats them down, and they're not prepared for it, they're like, Okay, I'm gonna go back. It's kind of like you're always stepping in and stepping out, you're always trying to do, we're built to be comfortable. And in a comfort zone. And I always tell people to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. That's the only way you grow. That's the only way you get out there and do things. And it's and that works with writing as well. Because I know you as well as you do this many screenwriters out there who live in their box, and they do their box well, and they don't generally jump out of their genre that their style. You know, that's why I love people like, you know, Tarantino who stays within his box, but man, he's jumped into every genre possible, and just throws his flavor into every genre. Same thing with Kubrick, when Kubrick was was doing his masterpieces, I mean, he literally made the definitive film of every genre that he walked into, essentially, so so I was just I wanted to get your opinion in regards to the neuroscience behind that and the in the how it affects us as screenwriters and as creatives.

Paul Gulino 38:22

Well, I'm, I'm certainly not a neuroscientist.

Alex Ferrari 38:24

I don't, neither, neither am I, but from

Paul Gulino 38:27

from, I have several patients I'm going to be operating on later today. Because you know, you everybody's got to make a little money on the side of

Alex Ferrari 38:36

neuroscience is a nice side hustle.

Paul Gulino 38:39

Yeah. You can do a series of multiple surgeries for the same issue. But there it is true. What I that are to talk about the reptilian brain, our two most basic impulses are hoping fear, emotions are hoping to fear okay. And, and fear is actually what you're describing, saying that safebox fears actually stronger than hope. And the example that I heard from one psychology professor was that if you are in a restaurant, and you get this, you know, a fancy restaurant with a wonderful seafood plate, you know, with all this all the fixings and everything, and you're about to eat it and you see a roach cockroach in it. That's it, you're done. Okay, you're not going there, you're not going to touch it. Contrast that suppose your sit down to a meal, and it's covered with roaches, and you see one, you know, artichokes? You're not going to say, yeah, look at that. I get an artichoke out of it. You don't you don't touch it. So that's the example they gave the top and fear. Now something else that's useful that we didn't talk about in this book. But it's another thing that I think is useful for when writers work with characters is this narrative theory of of psychological development. Because you're talking about people that say the posterity was different, that, that the idea is that we, up till age, by the time we get to age three, we have developed a narrative of our lives. And we tend to notice the things that confirm that narrative and ignore the facts that don't. This leads to all kinds of neuroses. I mean, like, you know, I'm the one who never was loved. So I'm unlovable, okay, someone throws himself at you. That's an aberration. That's not doesn't fit, you know. And there was this episode of a senator I forget his name a senate US Senator A few years ago, who was caught having sex with men in bathrooms in Minneapolis. Right. Okay. So what? What was his story? Well, he was married, and he again, and he's a he's a straight man. Right? Well, that's the story, he tells himself. The fact that he's meeting strange men and having sex with them, gets ignored in that narrative. It's like, Oh, I don't know what that is. But that has nothing to do with who I am. What I am, is a straight man with a family and all that. And in a way, this guy is living two different lives, you know, what he's aware of, and one that he blocked out? I can't speak to him. He's not my patient. I don't know. I'm not a psychiatrist. But you can see that process happening, that it's possible that a guy who's spent 50 years of his life, he's like, 6050 years of his life, suppressing some reality, and construct a reality in which he was not gay. If he ever came at 865, to realization that he was gay, that's 50 years of your life that you're a stranger.

Alex Ferrari 41:44

It's dead. It's devastating. It's devastating.

Paul Gulino 41:47

Yeah. We should put that away.

Alex Ferrari 41:49

So that so let me so let's turn this into something for for screenwriters in regards to the the script, the screenwriting guys who's listening? No, because I mean, listen, I could talk neuroscience all day. But the but the concept for for character development, this is so powerful. And it's such a powerful tool to use as a screenwriter to get into psychology and to get into almost the like, just the concept of what we just talked about, adding that, that sub layer that, that that that thing underneath of the that underlining thing is like, I have to stay in this safe Spock's perfect example a guy who's been, you know, 50 years saying, I'm married, I have kids, but then I go off. I mean, that's, and and exploring why he did that. That's a story. That's a screenplay, or the person who has a wife and kids and he's a serial killer, you know, on the side, and we've seen those kind of movies, like they they literally compart my compartment. I can't say the word you know what I'm saying? To mentalize Thank you, sir. I'm a little bit, but they're but they put their their worlds in different boxes as almost a defense mechanism for themselves. So someone like this, the guy you're talking about this politician, he literally was doing this to protect himself in his mind. Like, that's that other story, which is his true nature. He couldn't for whatever reason, the way he was raised his environment, his social group or community wouldn't accept that. So he suppressed it. And now it comes out in this very strange way, years later, because it can't You can't hold something like that in it's not something you can maybe hold it at bay for decades. But eventually it will come out that is such a powerful,

Paul Gulino 43:39

a character development tool, the difference between the story you tell yourself about yourself, and the reality when that collapses, that's huge. And the way you can use it in screenwriting, you know, a lot of people like, I think creating characters, it's, it is kind of a mysterious process, people come up with him, some people are very good at it, some have more plot driven or that kind of thing. They divided that way. stories and characters are more primitive. But usually people try to write a background about that character, okay, he was raised this, he did this. And that's useful to generate ideas. But the other thing to think about is not what they went through, but what do they tell themselves about what they went through? What is it because this is really important, when you're when you're writing a screenplay, when you're even plotting it out? The character doesn't know what the story is about. They think it's about something completely other than what what you're in the journey here, but I'm going to put them up. So where is their head? Where is your characters thinking things are going to go? What's the narrative that they're telling themselves, while you're plotting while you're God? doing all kinds of things to their lives? So in that sense, to give a little thought to this question, when you're thinking about coming up with a character when you're trying to come up with the specifics of a character, what are the what are they? What do they think about themselves? What's their image of themselves? And their story really their story of themselves. And and we certainly we do exist in a story, you know, we do that

Alex Ferrari 45:07

as a defense mechanism defense mechanism for our own sake, you know, just for us to be able to, to continue to it's a story stories are so powerful that we tell ourselves stories just so we can make sense of this insane thing called life. And I think that's one of the powers of story, it is a way for art in general is a way for us to process just being alive and just generally, so we're always looking for something to just grab on to and story is such a powerful thing. Would you agree with that?

Paul Gulino 45:36

Yeah, well, let me tell you some practical things for your students how to apply that. That was the first lesson that Frank Daniel, I mean, I have it in my notes from the first day of the first class was that your job as a screenwriter is to turn the audience into keen observers of detail, that you are going to give them clues. And when you give them the clues, you do it in such a way that they're going to anticipate where you're going. And once you've got them, anticipating where you're going, you got and you can do all kinds of things with that. And that idea was formula I studied with him in 79 to 82. Okay, in 1985, a theorist named David bordwell, actually took that idea. Now, he didn't get it from Frank Daniele, he did it himself. He came out with a book called narration in the fiction self. So there was a very influential narratology in the study of narrative in academic world, and he applied constructivist psychology to how we comprehend movies, that in other words, we're not sitting back in just absorbing, we're actively involved in anticipating. And that's how we go through life. I was telling you about how we assume things about the world. Well, I can give you clues. I could tell you a simple story now. And it's like that. Suppose I show you a movie. You're watching a movie, and in this movie, you have a man, and he goes to a flower shop. And he gets flowers, and he puts on the on the flowers, Happy anniversary, and he gets a box of chocolate, okay. And he's, he goes, he's heading home. Meanwhile, his wife gets up, you know, she gets herself all attractive, and negligee and all that, and at home. And then she gets out a gun. And she puts the gun in the drawer of the nightstand. Okay, so where are we going with it? I just tell you that much. You got a pretty good idea that he's planning to make love and she's planning to make war. Okay. That's how it's going to read. I can pretty much assume that there may be some people who think, well, I really have no idea what's going to happen. But I think most people are going to say, shit, he's have a lot of trouble. Okay, so then he comes home, and presents her with the flowers and chocolates, she reaches for the drawer opens it up and says Happy Anniversary that turns up. He's a gun collector. And this is the gun that he's been hoping for. And she's been saving for a year to get him this gun. Okay. We have a twist, we just, I just told two stories, the one you thought you were seeing and the one you're actually saying, right? That's all twisted. But I rely on giving you clues. And assuming that the audience is going to put them together. Now then I then she takes a piece of chocolate, she gets sick. And and then it turns out he poisoned stock. Okay. There's another trip, I give you that information. I just I decide what information to give you and what to withhold. And that's one of the things that Daniel mentioned. He said, there's really three questions when you're developing a story. When you're in the ideation stage, and you're trying to figure it out on the outline stage, be cheap. The three questions are of course, what is the main character want? What are they trying to avoid? Okay. The second is, what does the main character know? And what is the main character not know? And the third is what does the audience know? And what is the audience not know. And based on those three things that's going to determine how your story plays. And a story can be. It's, it's a difference between the story and the telling of the story are in narratology terms, terms, the narrative, which is the story and the narration, which is the telling of it. Another example I could give you. There's this there's this man, he's at the doctor, right? And he tells the doctor, I'm really worried about my wife. I think she's getting Harvard here. Okay. And, but I'm afraid to bring it up with her because she's concerned about you know, maybe she'd be offended. I'm getting older and all that sensitive to a doctor says very simple. Go home tonight. Get a certain distance away, talk to her in your normal voice and keep getting gradually closer until she can hear you. Right. And then you'll know if there's really a problem because if there's no problem, you'll know. So it goes home and she's over in the kitchen and he's in The living room, you know, the doors open. And he's sitting on the couch and he just says in his normal voice, darling, what's for dinner? Okay, so he gets up and he goes to the edge of the kitchen when the door is open, he says, normal voice, darling, what's for dinner? Nothing. So then he goes into the right into the kitchen. Darling, what's for dinner? Nothing. So finally it gets right behind her, and says, darling, what's for dinner? She says, for the fourth time chicken.

Like, alright, the story was a man is hard of hearing. But he thinks that his wife, who's hard of hearing, the doctor tells him to go home and do this test, he does a test, and then discovers that it's actually he's one of those artists here. If I tell it that way, you're not going to go, it's not going to go anywhere, right. But if I withhold certain information, I tell you the same story, but it plays differently. So that's one of the elements of constructivist psychology you can play with. And it's it's a, it's useful to realize, too, that audiences don't. When they go to a movie, they don't see a story they see seen at the scenes, and they construct the story based on the clues you give them in the team. That's all they ever see our feet, what they create the story in their minds. And knowing that you you realize you have this power that you can manipulate. Anyway, I'm sorry.

Alex Ferrari 51:30

The the the master of this of suspense, of course, is Mr. Hitchcock, which, and as you were saying the story I was thinking of psycho, which was a perfect example of that he played on the audience knowledge of Janet Lee as a big movie star. And they thought and they went down this road with her. And they're like, well, she's, I mean, obviously, she's the movie star. Nothing is going to happen to her. And 20 minutes in. She's gone. You know, sorry, spoiler spoiler alert, guys, she gets killed in the shower scene. Yeah, she gets killed in the shower scene. So now the audience has nobody to hold on to. And now they're handed over to this weird dude at the hotel motel. And now he becomes the main character in the middle which was completely revolutionary at the time and you know, West Craven did it again with the scream in a smaller way at the beginning of scream as well. They do that like just kill off the the but but the thing is that they carriage you along. And it was this whole narrative that he the whole narrative that he was talking about, like the money and she was running and then the cop pulls her over. And it was all Bs, is it he was completely leading them down the wrong way. Like, no, we're just gonna kill her. And now it's really about this. That's brilliant storytelling.

Paul Gulino 52:50

He played the audience. And I think that's a great example. I'm glad you brought up a great example about I know you had another guest though a while ago, and said, Carly glacius. I think he said he echoed what I what I think is that, if you if you think about rules, because you always hear here's the conversation. I hear the film school all the time. Because it's like, somebody we watch us a student film, and it's kind of underwhelming and somebody says not that are our students always have breakdowns,

Alex Ferrari 53:18

obviously. Obviously,

Paul Gulino 53:21

university for God's sake. All right. So somebody will say, Well, you know what, they really got to learn the rules, you know, filmmaking storytelling. And someone else would say, Yeah, but you got to break the rules. And then someone else will say that you're gonna learn the rules before you break the rules. And then somebody else will say, how about lunch? Let's go to lunch. I love it. You know, it just goes, this conversation never goes anywhere. Or I'll hear someone say, Well, he broke the rules. But he was Hitchcockian a breakthrough. What does that mean, that doesn't help you as a writer? Well, if you don't, instead of asking, what's the rule, ask what's the effect? See, if you follow the rules, and I've seen students do this, they'll follow every rule, and they want me to go like this. Hey, congratulations, you follow the rules? The rules don't apply to you. And they don't pay you. And, and following them means you're a follower. But if you ask, what's the effect of my choice, storytelling choice on the audience, then that puts me in the power position, I'm the one deciding the effect. And audiences do applaud, and they do pay for it. So think about what's the effect of what your choices are. So for example, with psycho is a good example of a schema, you just mentioned the schema if you have a major star, and audiences are used to seeing major stars in movies, and they're used to seeing them all the way through the movie, they may die at the end, but they're used to seeing them all the way through the movie. And the producers who paid money, a lot of money for that car, they want to wait to the movie to get their money's worth from it, then that's what the expectation is gonna be. So and another thing we talked about how audiences can To a main character, well, you use that as a way in a traditional drama, not like an ensemble, but it's a drama, like a traditional drama with a single protagonist, that that's where the audience connection. So you're going to keep them interested because that person is alive. Okay, so you have a lot of powerful things going on. And then, but then if you violate that, if you break that, like, like Scott did, the question isn't, he was bad because he broke a rule, it's hard to get away with that. He didn't have the connection to the main character sustained audience interest through the movie. So what did he do instead? And what he did you mentioned, he dwelled and he did it intentionally. He dwelled for a long time on getting the base to cover it up. And he really took a long time, they could have just caught away, and it's all cleaned up. But he washed it out. And he's cleaning it up. And he's doing this and he's barely putting the body in there. And it's now by that time, we've connected to somebody and we've connected to a young man who's desperately trying to cover up something his mother dead. That's the story. And we're or

Alex Ferrari 56:15

is it? Or

Paul Gulino 56:17

is it a path? What do you know what you think? And I'll give you one more example of the of how, you know the contrast between following rules and, and going for effect, okay. Let's say you wanted to write a book about how to tell a mathema joke, right? What would you do, you would go around inside every Knock Knock joke you could find. And you would come to some general conclusions about it, you would write the book, and you would say, in order to tell a mathematic joke, you have to have you start out by saying Knock knock, the other person will say who's there? Then you give a partial answer. And then they say partial answer who would repeat it back? And then you give the full answer with a choice. That's how you do it. Those are the rules. Okay, so let me let me try this. Knock, knock.

Alex Ferrari 57:08

Who's there?

Paul Gulino 57:10

control freak. Okay. Now, here's what you say, control freak who think that, right? I just broke the rules. But I didn't. What the effect I wanted was a laugh, not talk rules. So I relied on the team of Knock Knock joke, to get the effect I wanted, which was the laugh rather than to simply deliver another knock that joke of a different Thank you. But so this is the world of prank Danielle got me into which is playing games with the audience. And ultimately, strategizing on how to keep the audience wondering what's going to happen next. And if you can do that, if you know how to do that. You can do anything with them in a feature film. And you can pivot into streaming, you can pivot into stage, one x 10 minute plays, what it doesn't matter, you understand what, how to grab them and how to keep them, it puts you in a real power position. So we were not taught, like, by page 30. This by date 60. This by page 90, they weren't really taught that or we were discouraged from following formula. Actually, the one formula we were told to follow was stories about exciting people told in an exciting way. You know, if you if you use that formula, you're asking the right questions, what's an exciting character? And what is how do you tell that story? That way? It doesn't mean that you're not going to see the patterns, because often you will. And if you don't have any other resource I know, I know a really successful very good writer who learned from fifield says read the book, and she's done one and I'm saying I've analyzed the films for the class, and they're like, terrific. So it's a tool that can help you. We were just taught in a different world where you're thinking about how it's affecting your audience. And yes, we Frank Danielle, did the three act structure that I hear people say well Sinfield give up a three act structure. There was actually a book that came out the year before screenplay that espouse the three act structure, but it just didn't catch on. I forget what it was called. But Frank, Danielle 79 has been talking about it for years. And, of course, you can trace it, you can trace it to Aristotle. It's it becomes explicit. There's a book called playmaking by Archer to get the guy's first name came out in 1901. Lightning, and he described essentially a three act structure. He said plays tend to be five acts, but it really three, you know, set up developing resolution. It's been around a while, but as I say, it's really we, the way I approached it, it's a tool for getting up into this mode of hope and fear, which is what sustains our interest. And then you go from there. So if you want to use that tool, use it.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:10

Your brain, it's exactly what you're saying is like, if it works for the outcome that you're trying to achieve, then use it if you want to use a hammer, or if you want to use an iPhone to get that that nail in the into the wood while you're building the house. It's your choice, one tool probably will do it better than the other. And is that less expensive, but whatever works for you, that makes sense for you and what you're trying to achieve. You should use I'm not sure if that analogy works or not. But

Paul Gulino 1:00:38

yeah, well, I mean, if you want to destroy your iPhone, then that's what you you use the iPhone or the hammer, you know, the hammer, you say for other jobs, right? Maybe a hammer

Alex Ferrari 1:00:49

or a wrench, let's say a wrench, you could use a wrench to get it in as opposed to a hammer. But the hammer is better prepared to you know, better built to do some kind of job. So I think all these tools, all these methods, all these techniques that all of these authors and gurus and and just teachers from throughout history have thrown on us. That's exactly what they are their tools, their techniques, and they put them in your toolbox and you bring them out to achieve the what you achieve what you want to achieve. Yeah,

Paul Gulino 1:01:21

yeah. And there's other tools too, that I've talked about with the students that that I've noticed filmmakers use to keep us wondering what's coming up next. And sometimes you can sustain a whole movie with him. Sometimes you really can't you need to help other tools. But something like what Frank Tanja used to call advertising, I don't like that term, I use telegraphing. It's essentially telling the audience literally where the show was going. Because a drama, unlike a novel, novel have usually there happened in the past, you got a narrator that tells you drama, since Greek times was something that was about to happen right in front of you. And they were both they've been written to the present tense their instructions for actor and that set people about what to do for something you're going to create right in front of the audience. And so it's particularly important to keep the audience attention in the future anticipating and so you can have something called an appointment. You've seen it use a movie, you know, Micha Jerry's use a terrier five o'clock. Yeah. And then because film is selected, you don't just turn the camera on and run it, you cut to different places, when you arrive at Jerry's carrier, the that confused about that? You know, you don't know, you know why you're there. So you maintain anticipation. And also, you're not coherent. Another one that can be used as a deadline, called a deadline, or a ticking clock, you know, you've got five days to bring the Duke back, you know, by midnight Friday, or you're uncooked, you know, that, you do that. And it's done in toy store. You mean from the get go? These guys knew what they were doing the original one. It's the birth, the move is in a week. Right? So we know that we have one week that this story is going to take place in a week. And that helps us because we've all I think have the experience of being in a movie where you thought it was over. And then it just keeps going. keeps going.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:25

That would be the end of Lord of Rings, Lord of the Rings, eight endings, and we're just like, Are you kidding me? Peter, come on, let's move on.

Paul Gulino 1:03:34

Yeah, I remember I had a friend a bunch of us, like we're teenagers went to the, to the opening of the first one, you know, get together in the theater, a bunch of colleagues, and one of them had, just before the movie started, you got one of the big Gulf waters. But you know, I said, You're not gonna make it. There's no intermission. I was right. Anyway. See, the problem is that the filmmaker hasn't signaled properly when the big moment is because we do emotionally save ourselves for these big moments. And so a deadline can help with that. But you put a framework around it. The one that I like the example I like to give it. But instead American Beauty where it starts out with a year I'll be dead. Right? There the deadline for you. Yep. So what it does is it it lets us it lets the audience relax and not wonder where this is going. You don't want to be wondering where it's going. You want them to be anticipate. So if you tell them where it's going, Okay, let's get there. Yeah. And

Alex Ferrari 1:04:27

that's what it's like. So American Beauty is a great example. I love doing this with movies. I did it with my, my, my last movie I directed, where I show a scene that's far from inside the movie closer to the end, at the very beginning to let everybody know, Oh, hell, this is gonna we're in for a treat. And you're waiting for like, you know, either there's a meltdown or a murder or something happens. And you know, it's not a surprise that there's a murder. We all know that someone's going to get killed, but like, who did it and when are we going to get to that point and now Now you're on the ride with him. So I love that technique as

Paul Gulino 1:05:05

Sunset Boulevard with my students.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:09

It's a great player. I mean, if you remember the player, there's so many of those, that technique is so powerful. If you do it properly, you you show that that little bit of information at the beginning you're like, what do you mean someone's gonna die like and then all your into now you're completely connected to these characters? Like, when am I going to see that? When am I going to see the tiger come out? This is basically where we've, we've been informed that the tiger is there. And he killed somebody. And we're like, Where is the tiger? When is this? When is the hammer gonna drop? And I love that I love speaking of suspense, because again, I'm a huge Hitchcock Hitchcock fan, and I never, I've never heard anyone Express explain suspense better than Hitchcock. Which is the the bomb underneath the underneath the table? Can you tell that story?

Paul Gulino 1:05:57

Oh, yeah, that's the idea is that you can stay in suspense longer than surprised, is the effect of surprises. 15 seconds, I think. suspense, maybe 15 minutes. So the difference would be that if you have two people sitting in a cafe talking, and then a bomb blows up, okay, you have a shock effect. But if you reveal to the audience, ahead of time that there's a bomb under the table, then every line of dialogue is imbued with this dramatic irony. And every line of dialogue has a double meaning. I mean, when somebody says, Do you think I should get another coffee? Well, I'm not sure you know, I'm tick, tick, tick, tick, tick. Suddenly, that innocuous line has a huge impact. And that's another one of the tools is dramatic irony. I have to let my students know, you know, the characters don't have to know everything all the time. You can, you know, reveal things and just not them see certain things.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:55

But what was the big rule? But what was the big rule that Hitchcock said that you cannot break when doing that technique? Do

you remember?

Paul Gulino 1:07:03

Oh, no.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:05

So the technique of suspense is he goes, he did it once in a movie, and the audience was very, very angry at him, which is you show them the bomb, and it's ticking. But under no circumstances can that bomb go off and kill the characters? You cannot let that happen. He goes, because the audience will be very angry with you. If you kill them actually, like surprise, that's fine. But if you tell and you torture them for 15 minutes, and then you still kill them, then you lose the audience. And I was like, that's it. He was he did it in one of his early movies. I forgot his foreign correspondent or something like that, where there was a bomb on the on the bus. And we knew the bomb was on the bus and it was ticking and it blew up. And everyone was like, No, no, no, no, no, no, no, you can't. There's a contract. There's a contract. We have an agreement here. You can't do something like that. So you know, that's a rule that I haven't seen broken very often. I mean, in a suspenseful situation. in that specific scenario, you can't blow up the characters. You just can't.

Paul Gulino 1:08:05

Yeah. Because you know, I happen to have a script right now that I'm working on, where I killed out characters, I'm gonna change that change it

Alex Ferrari 1:08:12

right away. Mr. Hitchcock said, No, I'm gonna ask you a few questions, because I could keep talking to you, Paul, for about another two, three hours. But I know you're busy man. You've got fresh minds, you have fresh minds to teach. So I want to

Paul Gulino 1:08:26

I want to say one more thing about the deadline thing. There are a couple of movies that they do that you I've seen that sustain an audience interest and those primarily through that purpose through that means one of them was The Hurt Locker. Now that's a that's a huge I don't know if you saw that. But it's a countdown. So the screenwriter there is he seems to be able to write these micro realistic scenes were very vivid. But it freed him to just explore these different situations. As long as we're reminded once in a while that we're ticking down to day zero. And we know it's going somewhere. So we

Alex Ferrari 1:09:03

like high noon, like High Noon eventually. Yeah,

Paul Gulino 1:09:05

I do another one 500 Days of Summer didn't go exactly North but eventually when you know that when you get to 499 the movies almost so you know or Julia Julia You know, there was Yeah, different recipe every day when you get the recipe 350 we're close to being at the end. So you can do that to frame things and then it frees you to to explore other kinds of drama. Anyway, okay,

Alex Ferrari 1:09:31

it is a it's a kind of roadmap for the audience like at the end of it like at 12 o'clock all Hell's gonna break loose at 365 recipes. We're pretty much gonna be close to the end of this thing. So it's kind of

Paul Gulino 1:09:46

chocolate cake by that point. You know the really rich prospect but perfect.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:50

So perfect example with Julia Julia which I love that movie. By the way, imagine if you've made that agreement with the audience at the beginning and at the at the at the A 365 she's like, you know, there's another book I'm gonna do and you go on and like, and that's like, and you just, she's just like, you know, I want to do another blog, and I'm just gonna end that's in the movie keeps going. Can you imagine that movie would be horrible? You'd be like, No, no, no, no, we there was an agreement here. You can break that you can break that agreement here and there. But you've got to be careful with how you do it. You know what I mean? That may suffer. But I could just thinking how horrible that movie would be. Like, let's say high noon, at noon, they're like, four o'clock. We're just not we're

Paul Gulino 1:10:32

a bit late, right?

Alex Ferrari 1:10:35

Where we did a shoot out here, but there's three other guys coming at four. So we're just gonna keep going. Like you can't.

Paul Gulino 1:10:45

You've got to keep that promise or people will turn on you without question.

Alex Ferrari 1:10:50

So I'm going to ask you a few. A few questions. I asked all my guests and what's specific to you? That I've never asked before the show and I want to I'm going to start asking all of my guests. What are three screenplays every screenwriter should read

Paul Gulino 1:11:03

three screenplays that every screenwriter should read? Boy. You know what I so closely identify the screenplay with the movie button, you know the style of like, I consider Billy Wilder like the guy who could teach me any of his movies. It's like a textbook on how to write a screenplay. But the screenplays that he was writing, were done. They were called continuity. And this thought was very different. Or Preston Sturges I love Preston circus. Yeah, if you're going to read a screenplay and really enjoy it, any of the Preston Sturges comedies from the early 40s will get you there.

Alex Ferrari 1:11:45

And also of his travels, also of his truck, yes.

Paul Gulino 1:11:48

All right. But just be prepared that it's not going to be in the master sequence, Master scene format, it's going to be in the continuity with the sequences marked, you know, sequences a through whatever they were doing. Okay, the screenplays that I've loved, if there's the one screenplay, and one of my favorite movies, is called trouble in paradise. Number 1932, the first talkie romantic comedy, and arguably still the best one. And it's in. It's in a book called three screen comedies by Samson raphaelson. So you can actually get that book and read that and I happened to read that script before I saw the movie because the movie was finished when I was young, you know, we didn't have VHS, we couldn't get the movie. It was tied up somewhere. So I had to record. But but that script was so you can see this students every step of the function. See this? It's, it was one of these, it's one of my pet peeves about a lot of films I see nowadays. It's about how the third act is like, usually too predictable, because there's a misunderstanding of what the third act is. But that's another podcast. But in this one, for example, what is that I'm reading this and I'm turning the pages of this comedy. And I have no idea how they're gonna solve this problem. I think that's it. Yeah. It's like, all these different elements are coming into play. It's like, no, there is no way for this guy to get out of here. You know, it's not even can you run faster or jump higher. It's like, running faster jumping. That's not going to even help out here. He's, like, trapped anyway. So that's raphaelson one of Raphael Sims, Billy Wilder. Double Indemnity is a terrific one. Because you can learn about indirection with a dialogue. You know, what a lot of people call subtext, I use a slightly different term. But how the characters are speaking metaphorically. So they don't have to reveal what there really, is there. Is

Alex Ferrari 1:13:47

there any movies in the last, let's say 20 years in the 2000s? that that that screenplay, you're like, man, you've got to read this.

Paul Gulino 1:13:57

I don't know if I've, I've seen some good, obviously, some really good movies, but I scripts I've read no recent movies that I read recently anymore. Which kind of breaks the rules a little bit is in Bruce. I'd like to show that after I show a classic like Toy Story. I mean, I've read the script. It's a great script to read. But it's I think it's a conforming script. It's one that they wrote after the the animation is a little different. They when they get to the end, then they write the script that is that maybe the you know the stars are gonna actually read because it's linked up to that thing, but that's alright, that's 25 years ago now that was

Alex Ferrari 1:14:39

fair enough. You know, I don't want to put you on the spot. It's fine.

Paul Gulino 1:14:42

But I've read know the in Bruges is very literate. I liked it. But he I'd say the script was flawed compared to the movie because the the I think it was interesting.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:53

It's always interesting. Sometimes the script is so much better than movie and sometimes the movie is so much better than the script. Right? He

Paul Gulino 1:14:59

definitely cut Some things out of there just like Well, everybody does. I mean, I don't even know if you know if you know, Sunset Boulevard, there was an opening there that was cut out. Did you know that? No, I didn't. Yeah, it starts out in the morgue. With him talking to the other dead bodies. I'll explain. Well, how'd you get here? Well, I'll tell you my story. And when they test screened if they shot it, when they test screened it, they found out that people were laughing too hard. And then they didn't know how to take the rest of the movie. They thought it was straight up comedy. Well, I

Alex Ferrari 1:15:29

mean, they said to a body talking to other bodies, and yeah, I mean, right.

Paul Gulino 1:15:34

So that you can read the script, I think, no, I'd never read. I'd never got to read that version of the script. But anyway, in bruises, very literate. That's a good script to read, I think. But, yeah,

Alex Ferrari 1:15:49

that's plenty good ones. That's, that's plenty. That's plenty of homework for everybody.

Paul Gulino 1:15:54

Okay. Now, what

Alex Ferrari 1:15:55

advice would you give a screenwriter wanting to break into the business today?

Paul Gulino 1:16:00

Yeah, well, that is probably going to sound familiar to you and the other guests, but obviously reading screenplays, I've you asked about reading screenplays, I have read that many lately. But when I was when I was younger, when I was learning, that's what you do. You have to read the screenplays and find out how they read and what, you know, how things are expressed. So you read a lot of those, and then you write them. And you just keep writing. And I am the the persuasion that you write what you're really passionate about without concern about marketability. I mean, yes, you wanted to connect with people. But the there's another teacher I've heard interviewed, named, let's see, he talks about the Pitch Perfect, authentic script, that's the term he uses. I think it's a great term. The pitch perfect, authentic script. That's the one that's very unique that the the that is really your original voice that connects with people that don't be afraid of that, you know, write the things that are really exciting to you. And so doing that, and then just again, the same in history that's opened up you're talking about, I'm encouraging the screenwriters to take initiative and make their stuff. Make Yes,

Alex Ferrari 1:17:22

yeah. And nowadays, you definitely have the power to do so.

Paul Gulino 1:17:26

You if you wanted to do it in 1965, the other 260 millimeter black and white, think, sound and pray. And now you can choose something that they can't really tell Is it done with a million bucks, and you make it look good. Now you can look, don't worry about the gatekeepers to it, and you are going to learn and I'm doing a class though experimental class where the students were all writing queries, you know, the could be thing with five that we're doing five to seven minutes, they're doing seven to 15 minutes. But each student Right, right, seven minutes of a, of a continuing story that we're trying to the audience, and then we shoot it in January and see if it plays, you know, and get them. My hope is that, eventually develop it in a way that students leave film school with a credit on something that people maybe have seen. You can, right now the model of film school is make a short film, send it to festivals and pray because there's a market for short films in 100 years, it went out in the teens, when we went into features and cereal. The original cereals were actually what we call babies, now, they're about 1520 minute episodes. And that's what we're going to come back to that they can go they can do that, and have something marketable anyway, that that suggestion would be good to go, you could still do these things and and i think you get recognized that way and draw attention to yourself. And I do think this great many opportunities now than there ever was.

Alex Ferrari 1:18:59

What is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film business or in life?

Paul Gulino 1:19:06

Okay, so given that, the without trying to sound mysterious, it's understanding that you can, you can be living two lives when you think you're living in the one you're in. You know that you will learn this lesson that something you thought you knew you didn't really know. And that it you reassess how you how you understand saying, No.

Alex Ferrari 1:19:34

Now what did you learn from your biggest failure?

Paul Gulino 1:19:39

Learn from my biggest Oh, I'd like to tell you, I've had plenty of those. So I mean, this is a rich experience. same person I like. You've heard of the Duke of Wellington, the guy that beat Napoleon. He has a quote that I like to use frequently. If he wasn't always a winner. He had this disastrous campaign. paid in Spain a few years before he beat Napoleon, the Waterloo. And he commented on it. He said, Well, I learned what not to do. And that's always something. And the biggest lesson that I've learned from that he said from a failure,

Alex Ferrari 1:20:18

yeah, what's the What? What did you learn from your biggest failure?

Paul Gulino 1:20:22

I learned my biggest failure to, I guess the biggest thing would be to relax and focus on what you really want to make. And, and, and do that, you know, because I remember the experience was that out of film school, I developed a thesis screenplay, you know, and it actually got recognition. And it got me a William Morris agent. And I was like, this is really great. I'm on my way. But then, when that didn't sell, you know, he was like, Hey, what's the next project? And suddenly, I was in a different world, because I felt like they were watching me, like, and I was being I was trying to create, under these circumstances of desperately, you know, and it changed my process, I didn't know enough to just say, whatever, I'm gonna do what I'm gonna do, and you'll like it or not. So that that was a failure. That was an opportunity that was met. And it was.

Alex Ferrari 1:21:22

Now what was the what was the fear that you had to overcome to write your first screenplay? Was that big fear that you had to overcome?

Paul Gulino 1:21:31

Oh, the biggest fear to overcome when I was writing that first screenplay, I suppose whether I had enough story, you know, remember, I was under the guidance of a master? Who is that, you know, factor that was not only a teacher, he did produce and write a lot of films in Czechoslovakia and one Academy Award for shop on Main Street 1965. But there's certain decades, so we actually knew the process inside and outside. So I had that, that guy, but still, when I'm just when you're just trying to when I was just trying to get ideas together about how I would do this. You know, what sort of story there I suppose that that might have been it.

Alex Ferrari 1:22:17

Okay. And three of your favorite films of all time.

Paul Gulino 1:22:22

That one, you know that that kind of changes? Depends every day? Ah, I am with it. But I would certainly put the trouble in paradise. Up there. It's defining that movie. Yeah, put it on. I'll watch it again. You know, that kind of movie? I certainly, what else? I mean, there's so many amazing ones. I did, I really think from the point of view of pure craftsmanship, took the first toy stories is a remarkable accomplishment. I was actually invited to give a lecture at Disney Animation a little while ago. And guess what I use that movie. I said, I don't know what process they used to work this. But here, I'm going to show you what they were doing. And it's just in 80 minutes, you know, the stuff that they did? What else if I may I love Lawrence of Arabia. That's another textbook

Alex Ferrari 1:23:23

of cinema in general,

Paul Gulino 1:23:24

a seven month period. I guess that dates me a little older films, but that's dead. So

Alex Ferrari 1:23:32

those are three good ones. Yes, three good ones they've been on the show before. So it's except for trouble in paradise. It is the first time that's been on the show. So but you have very good choices.

Paul Gulino 1:23:41