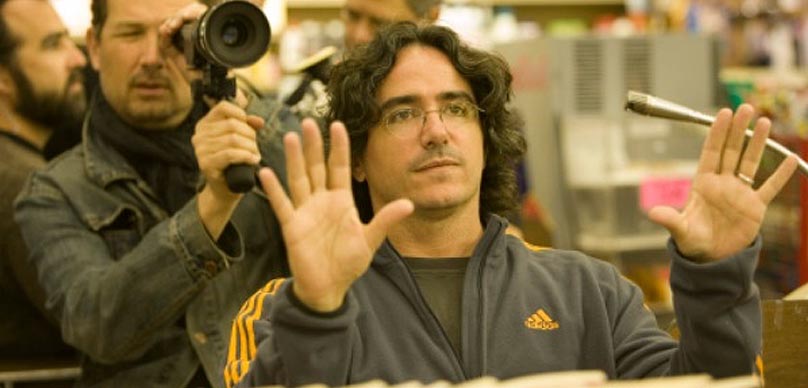

Today on the show we have writer, producer and director Brad Silberling. I had the pleasure of meeting Brad back in 2005 at my first Sundance Film Festival. He was very kind with his time and gave me some great advice.

His feature films include City of Angels starring Meg Ryan and Nicholas Cage, Moonlight Mile, starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Dustin Hoffman and Susan Sarandon; Lemony Snickett’s A Series of Unfortunate Events, starring Jim Carrey and Meryl Streep; 10 Items of Less starring Morgan Freeman, Land of The Lost starring Will Ferrell, as well as his debut film, the family classic Casper, produced by Steven Spielberg.

In television, his growing stable of hit series include the critically acclaimed comedy Jane The Virgin as well as the period drama Reign, contemporary reboots Dynasty and Charmed, and the new Disney Plus series Diary of A Future President. He is a graduate of the UCLA School of Theater Film and Television where he earned his masters degree in production, following his bachelor’s degree in English from UC Santa Barbara.

Brad and I had an amazing talk about the business, warts and all, what it was like having Steven Spielberg as a mentor and how he built his directing career.

Enjoy my conversation with Brad Silberling.

Right-click here to download the MP3

Alex Ferrari 0:00

I like to welcome to the show Brad Silberling. Hey, doing that, Brad.

Brad Silberling 0:16

Excellent, man, how are you?

Alex Ferrari 0:17

I'm doing great, man. Thank you so much for coming on the show. Man. I am. I am humbled and honored as I was telling you before you and I met in 2005, at my first Sundance, and you were speaking had a fantastic panel and I got a picture with you. I'll see if I could put it in the show notes. I have it. I have it in my archive somewhere. And you were always You're very kind to a young filmmaker just asking price stupid questions. Like, how do I get an agent? Like, you know, like, dumb pie stuff at the time, but you were very kind. I never forgot you. And I followed your career as as you moved forward. And I just the other day, I was like, you know, I got to get Brad on the show, see if he'd be interested in coming on the show. And here you are, sir.

Brad Silberling 0:59

Here I am direct from the San Fernando Valley to you.

Alex Ferrari 1:04

So how did you so how did you get started in this ridiculous business that we we love so much?

Brad Silberling 1:13

I you know, I'm not alone. I was a kid with a camera. I was a kid with a Super Eight camera here in the Valley. And it's interesting because I so my dad, who passed away eight years ago, he was a documentary producer. He was born in DC because he was working for the US IA, which is actually our government's propaganda arm. We do have one. No, no, no, he was producing documentaries during the Kennedy administration. And only in the 60s would logic have dictated that he would move from that job into network television. Don't ask how they made that leap. It was a smaller business then. So we moved out to LA and 67. And he started working at at that point at ABC as a programming executive. So oddly enough, they thought his skills would translate. So he worked as a network executive the whole time I was growing up. But he always loved production. And so I took advantage of that by I would go beg to be dropped off at a set at any point I could, from probably about age nine. When I was old enough to ride a bike, I would steal over to universal, I'd met a really nice secretary who would like slip me call sheets and a drive on which was a bicycle. And I would spend every Friday afternoon there, but I just was fascinated by the process. And again, my dad was always coming at everything from from a story perspective. But I'm that guy who, you know, I still hadn't really picked up a camera I was just absorbing. And then I was there that first day. In 1975 First day for showing of jobs I made my dad dropped me off, there was a theater called the Plitt. That was in Century City where ABC was where he was working and I begged him to just drop me off. It was like an 11am showing. And I'm sitting there alone The theater was not full even though obviously days to come. It was going to be incredibly full, huge airplane kind of recliner seats. I'm alone in my row. And I get to the the the attack on the little Alex Kittner the kid on the raft. And I'm just having a heart attack. And I don't know if I can make it through the movie, looking around to see if there's anybody there. But I hung in thank God. And by the time it was done, I had that feeling which was who got to do that. Who did that? Who took me through that ride. That is something I will never get out of my system. And I went home that day and snuck into my dad's photography closet. It's still his he had a Mac it was a it was in a Minolta Super Eight camera and I started shooting that so that day I it was just like the switch was thrown and Stephens really funny about this because I'm not alone. I mean, I can tell you the number of other filmmakers who were switched on in that moment by that movie. And so I started shooting Yeah, so I was shooting all I did two things. In junior high school in high school, I shot movies and I played soccer and that was what I did. And this was to parade again where it was. I mean, I look at everybody now with their phones in what's possible. And back then you're shooting three and a half minute cartridges. Every second counted. You had to really so you're cutting in the camera. Are you really thinking through your material, your splicing your little, you know, super aid splices. But I, so that's what I did. And I was very obsessed. And I did that right up through, I got a lot of good advice to not do film as an undergrad. But to try to actually learn anything else have sort of more of an open humanist mind. Start writing. And so then I went to grad school and went to UCLA. And made you know, SC is more famous for its, you know, thesis, final films, whatever they're called. But I made, I made my thesis film, and I was fortunate we fought to have our first industry screening because UCLA was super egalitarian, and they didn't normally like things like that. But we did. And so coming out of that screening, I ended up going under contract, I went under contract universal. There had been a woman there who's still a great friend, Nancy Nayar, she ran casting at Universal, she was there just to troll for actors. She saw my film, and she said, Would you mind if I took your film Back to the studio and I was like, yeah?

Alex Ferrari 6:14

No, please, please don't.

Brad Silberling 6:17

Please, no. Can I walk you to your car. And so I got a really funny set of phone calls. One was from the TV group, and one was from the feature group. And again, at that point in time, they did not communicate, they still don't often. And they basically both wanted to try to put together some sort of deal. They hadn't really done term deals for directors since like the early 70s, like Spielberg, so when Steven Spielberg, Richard Donner, a number of these guys who basically were on term deals. And so they dusted off an old term deal. And they, they just like, he's young, he's cheap, hopefully, you know, some talent, let's do this. And they covered everything from writing, directing, producing, you know, making omelets, they, they, they had me, but it was incredible. So I was prepared to start, you know, parking cars at a grad school. But I went under contract. So that meant immediately trying to figure out who's producing on the lot is their television, who's making movies. And that became home for the first two and a half, three years that I got started. And then ironically, Steven bochco and his then sort of in house director, a really great guy named Greg Havlat. Saw my graduate film, and they said, Come over here. And universal was very wise, because they're like, good, let him go. Fuck up on their, on their dime. So but I so my first three years of work or directing television, primarily over budget goes company,Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 8:02

Oh, so I have to ask you though, because looking through your filmography, you have the distinct honor of being one of the directors, who directed an episode of the infamous cop rock.

Brad Silberling 8:14

I'm one of only 11. And the original order was for 12. And they killed it. I remember Stephen coming down that set one day. And he was like, well,

Alex Ferrari 8:27

This didn't work.

Brad Silberling 8:29

That was my second hour of television. It was crazy.

Alex Ferrari 8:33

I beat so for people. So people listening if you don't know what comp rock is, Google it on YouTube and watch a scene of cop rock. It was this musical cop show, which is it is such an oddity in television history, you know, from such a big I mean, Steven bochco was like he was the he was the dude, he was it. So it you know, it'd be the equivalent of I don't know, whoever nowadays, you know, big show runner, Shonda Rhimes doing a cop, cop musical. And it was I saw so I mean, I never seen a full episode because I wasn't I didn't see it when it got released. And I don't whatever's on YouTube. But I just remembered this cops just like singing about drugs. And it was just the weirdest thing. And when I saw it, I had to ask you, what was it like being inside of that?

Brad Silberling 9:23

Here's the truth of it that Steven had seen there was a great British series called The Singing Detective. And I think he was feeling his muscle and feeling his strength and thinking I can do anything. Let's do that. The problem is, Steven didn't really and God bless him. He passed away a few years ago, he was an amazing guy. He didn't really care about music. Didn't really like very much. So this was the problem. And you know, the whole idea of musicals is you only you only burst out into song when you have to when when when basically the spirit moves and the story needs it but He didn't approach it that way this, the cop rock outlines were like, normal Hill Street, it was like procedural procedural, maybe a song in here. And also a problem they weren't raised in, which meant that in production, they came very late. So it wasn't like you had this great champion, Steven Spielberg talks about this beautiful process. On my side story about working for six months, even as you're doing the choreography and just copra you would be shown the number on the day of shooting, because the music had only just gotten to the choreographer who's kind of winging it. And so all the actors like the fuck and and but it was recorded live in terms of the singing, which also is usually you do, you know, like a pre record? It was crazy. And and yet there there would be. There were numbers that kind of worked. And then there were a lot of them called groaners that were just like, Oh, no. And you just fell for these actors who had to commit. And you know, so it was a, it was an exercise in insanity. And like I said, it was not it. If somebody who just loved the musical form, had tried it, maybe before. But anyway, yeah, it was good. But that was my second hour television.

Alex Ferrari 11:25

So so this is his this is this, what I'm doing? Is this is this?

Brad Silberling 11:31

Great. Okay, you go over there. You danced a blocker, you get your gun, let's do this.

Alex Ferrari 11:36

And you've never directed a musical at this point in your life.

Brad Silberling 11:38

Oh, of course, of course.

Alex Ferrari 11:41

Because how many people have really directed musicals? So that list is fairly checked. All right. So you're there as a young How old are you at this point 22 23?

Brad Silberling 11:52

I was probably 25 20. Yeah, I was probably 25

Alex Ferrari 11:56

25 years old. Second time. My God. Alright, so let me let me ask you the first day because I always love asking this question the first day on the first job that you got after you signed that deal with Universal. When you walk on set, I gotta believe you're losing your mind. Your your imposter syndrome is running rampid you're like, any moment now? Security's gonna escort me off the lot. How did you like walk on and like, do your job with all of that? I mean, I'm assuming so am I correct?

Brad Silberling 12:30

You, right, you're assuming and your assumption would be correct. But for three, they all tell you two different stories, but for three things. One is I, you know, I even remember, when I got my contract, everyone was like, Oh, my God, are you losing your mind? And I wasn't, it wasn't hubris. But I felt like I'd been doing what I was doing for a long, long time. And I trusted myself. I felt like okay, I've got more than just the kid next door to be my crew. Now, this is good. So my crew got bigger. But the single biggest reason my Canadian friends are gonna kill me. But the single biggest reason I didn't fully have that was my first episode for universal ended up being in Toronto. They were doing a second batch of Alfred Hitchcock present, right. And so I i finagled my way into one of those. And I swear, I don't know what it was, but I was not intimidated by the Canadian crew. And I was working with awesome. I was working with Mike Connors, Matt Mannix, he was the lead. And he was couldn't have been more dear and awesome. And so I just thought, of course, why not me. So it that part didn't really overwhelm me, I felt fine. I'll tell you the moment that you're thinking of it was less imposture than just like, how did this happen? So that's my first directing job in television. My first feature directing job is Casper, and we're shooting in 1994. As I've told you, I picked up a camera because, um, Steven Steven ended up becoming my mentor and giving me my first feature job. And the first morning of our shoot, we were shooting in the big kitchen, there was a big long kitchen sequence that was gonna end up having more CG, then all of Jurassic Park was insane. He's awesome. He shows up at call to be there for my first shot. And we'd go into the hearse, and it's awesome. And when the time came to call action. I just sat there and he's next to me. And I'm looking at him. I'm looking at this whole situation. And it's like, everything just dropped on my head. I was dumbfounded by the universe. that this was actually the case that he just looked at me and smiled Newman say it as like, action. And it was, it was still one of the most incredible moments and it was just that that thing of confluence, like, how did this happen? I'm grateful it happened. But yeah, so in a weird way, that was my bigger moment. But I did, yeah, I had, maybe unfounded. But I did always have a belief that if you have the story, and you know what every setup is, and you're there, the crews gonna follow you doesn't mean that there's not going to be testing and that they're not going to sit there with their arms folded at times. You get all of that I had the DP on that very first. Alfred Hitchcock episode, by I don't know, it was like night number three, like wanting to quit. Because I'm very hands on. I don't just say, Yeah, let's go do a nice to shot and I'm going to go get some coffee. I, I'm still a kid with a camera. I set every shot, I, you know, I rehearse with the lens in my hand. I'm just who I am. And this guy wasn't used to that. And it was really funny. I've had that a few times, even in some of my movies where to pay. So I now my litmus test for whom I'm going to collaborate with as a DP in particular, it has to feel like a friend from film school. That's not a GISTIC. They can be 90. But it has to be that spirit. We're in this thing together. Oh, look, what I'm seeing. What are you seeing? Ooh, look at that. But those who work in such a way that it's like, I'm the director of photography, you go sit in your chair a little man. I'm just not there. So that was that was an interesting early moment for me with my confidence, but how to keep a collaborator close without losing them.

Alex Ferrari 16:54

Now, I heard I remember years ago, when Casper came across when Casper came out, it was a fairly big. It was a fairly big deal, because CG was just starting.

Brad Silberling 17:06

We were the first character with dialogue. CG animation. So Steven had done Jurassic and 93. And as he Yeah, that first morning, when he came to my set, and kitchen, he's like, Dude, you're about to blow through more spots than we did in the whole movie. And he's but he came, he came like week three. And he's like, oh, man, if you'd known what you're getting into, you'd never would have said yes to this. And I laughed. He said, You're now directing these characters. There's dialogue. There's monologues, there's soliloquy, he's, I just had to have the dude's turn and roar. And it was a deal. It was a deal. And it was we there was an early glimpse of motion capture that was experimented with, but it was not ready for primetime. So unfortunately, I didn't have that to go to. It was all here. And then I basically had to go with a with a old school 2d line animator, I had to go and basically, after making the movie, direct every performance in pencil sketch, right, then hey, then take those to ilm, and go through the whole so it was very handmade.

Alex Ferrari 18:23

Now what watching some behind the scenes or an interview that you did, was it true at one point that you turned down and said, I can't do this, and that Steven had to literally call you off the ledge?

Brad Silberling 18:37

Yeah, so he we met again, it's it's only he could have done this we met because he happened to see some television that I directed not a bochco show, but Gary David Goldberg who's passed away and he was amazing. We did family ties, but then he, Gary did a show called Brooklyn Bridge. That was really memens remembrances from his growing up in Brooklyn in the 50s. And I happen to direct an episode. I can say this because I'm a tribe member. But Gary said, yeah, you directed the least Jewy episode that we did. Because it was it was an episode about this kid and his family going to Ebbets Field to try out for this thing. And it was so non Jewy that it was more of an Americana episode. And they ran it and it's crazy. I was just thinking about this this morning. It was in thanksgiving of 91 So 30 years ago last few you know a month ago. It they ran this episode because they needed to fill the extra half hour after the first running CBS did have et so Stevens movie ran. They needed to fill a half hour they thought oh, this is very heartwarming, very Americana apps. So Gary called me the next week and said you're not gonna believe the phone call. I got that. And I said, Yeah. And he said, my friend, Steven Spielberg was obviously watching his own movie, and stayed through the commercial break. And he saw your show. And he called me and wanted to know who did it. So that's how I met Steven. So I went and sat down with Steven. And he happens like a Schwab story. He happened to see that episode. And he walked in his office and Amblin. And, you know, my hearts through my mouth at that point. He's the most disarming kind, warm human ever. So that goes away in 30 seconds. But he didn't even let me say anything. He said, Okay. Let me tell you about your last three years. And I look at him, and he proceeds to tell me exactly what I had been going through as a young director, under contract in television. And I'm like, my jaws hanging open. And he's loving it. And he said, Yeah, I know, I cuz I experienced that. And I saw what you did, I could see you were making a movie, but you only had a half hour to make it. And I'd like to help you make a longer movie. And so that, yeah, so that's what started us. Originally, he had in mind, much more reasonable first movie, it was like a little Louis mall film, there was a thing called the divorce club that we were going to do. That was about kids and divorce, kind of comedy drama, is Warner Brothers. And so when he went to go make Schindler's List, I was starting to prep that movie. But I noticed some real foot dragging from the studio about hiring like crew. And so I called Lucy Fisher's great producer now was the executive and I called her I said, Lucy, is there a problem? She said, I think you should call your friend Steven. I don't think they want to make this movie. And so I called him in Poland. And he was like, Hey, how's it going on your first movie? Isn't it amazing? Isn't it great? And I was like, Dude, I It's wonderful. But I don't think they want to make the movie. What? That's crazy. I'll call them and he called Terry Semel and Bob Dale. And he called me back two days later, he said, I'm so sorry. You're right. They don't they're scared of it. They think it's it's the subject is too sensitive. And he said, I don't know what to say. I'm so sorry. I'm like, don't worry about it. Go back to my day job. Thank you for trying. And that was the timing where I went back to bochco to direct one of the first 10 episodes of NYPD Blue so that Steven takes credit for my marriage because I ended up marrying Amy Brennaman who was in the cast of NYPD Blue the first season. But then he called me and he said, This is months later, I was doing a pilot in Hawaii for bochco, and he said, Okay, starts the call saying, Okay, this one's really going to happen. Promise it's gonna happen. With start date, I have a release date. And the moon is gonna, I said, the movies what? He's like, can you say, it's Casper? And I said Casper? Like is in the front? Yeah. Yeah, yeah. But it's gonna be live action. It's gonna be CG. I just did these dinosaurs. You're gonna be doing this and that. And I'm dumbfounded, you know. And I said to him, you know, which Brad you called? Because I was like, Dude, I, you know, I had no animation background, I'd done some small visual effects work in television, but I dated an animator at UCLA. It's like i i But I really didn't have any clothes. And he was amazing. He was like, know what you do. You're technically savvy, what you do and emotionally what you do and what this movie needs, is you? And so but I didn't just say yes. On the call. I had to take a weekend. Because I was overwhelmed by the prospect of mass failure.

Alex Ferrari 24:04

Yeah, because that's a that's a huge that was a that was a big movie when it came out.

Brad Silberling 24:08

Huge movie ended up where we knew would be it was like $65 million. At that point, this is in 95. And all of a sudden, they're in Hawaii, and I'm just thinking, Okay, if this movie works, Steven Spielberg presents great, great, great. If it doesn't work, I'm like one of those direct first time directors littering the beaches of Malibu who can't get a second job. And so I was really anxious about it. He did a very shrewd thing. What he did was he sent the young producer Cullen Wilson who was going to do the movie. He sent him to Hawaii with a trunk of basically, almost like illustrations from ilm, about how this could work. What the modeling would be like, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And I'm just driving around to scout my pilot with calling the whole weekend saying, I know this can't work I, you know. And then it was awesome because I had a conversation with with now my wife then girlfriend, Amy. And she's like, okay, it's like pros and cons. Why, you know, what are the pros and like, well, it's an incredible opportunity. And I love the fact that the movie is actually embracing this idea of loss and that there's an emotional storm. And she's like, okay, so what are the cons and like, I could tank? And so that's when I just realized, okay, the only thing keeping me from this is fear. I gotta fucking dive in. And so yeah, I called him back. And I said, Okay, let's go. And it was just like, lightning from there.

Alex Ferrari 25:50

That's amazing. Because I mean, I still remember when that movie came out I love the movie, when it came was such a heartwarming and touching film. But it was technically they everyone was just talking about the character and was just a first real use of animation as a as a talking characters. And yeah, they were go so you, you know it's not avatar. But but but without Casper, it's hard to get the avatar like you need a minute. It's part of the evolution. But it was so beautifully, even. It still holds to this day. It's still holds.

Brad Silberling 26:21

He, I was waiting. I was waiting for the big Yoda moment. And I was when I was in prep, to talk about the effects and about the effects work. And we're getting closer and closer to shooting. I'm like two weeks out. And Steven slows and talk to me about he had at one point said to me, oh, yeah, I'll have the office send you a couple of tapes of work sessions with ILM. You can see how I gave them notes on the dinosaurs. And so you'll know how to like yeah, okay, great. We shouldn't done it. So finally I said, Hey, can we grab five minutes? He's like, Yeah, great. Great. I said, Okay, well, first of all, I think this affects budget doesn't really reflect what it's going to be. And he looked at me with that great grant, he said, I wouldn't worry about it, just go shoot your movie. And I was like, Okay, this is the guy. This is his, like, Close Encounters thinking. I know, it's gonna be pretend it's the other number, but it's really going to be this. But more importantly, he said, again, what you know how to do you know how to stage beautifully, you know, how to, to really you know, where the camera goes, You know what to do to do an elegant job. in live action. Don't treat this any differently. You have to basically, just don't try to like compensate. Do it just as you would, but only you're going to know where those characters are. And you're going to have to communicate that. And that was exactly the right advice. So I stopped thinking, Well, I have to kind of put on a different filter. And I treated those four ghosts, just like any other character in the movie, and I'm going to stage with them, I'm going to counter the camera, the focus shift is going to happen because there's the moment it made me look like a madman on set. Because it's like orchestrating, you know, it getting the crew to understand where these ghosts were, how quick, they were moving, getting the camera operator to tilt at the right moment to an empty part of the set. And then, so I was doing this all the time. It was, it was crazy. But it felt completely natural. And that movie made me fearless. Because once you've done that, you can't throw anything at you that you know, and also it it I have friends who are live action directors who still have this envy of going to do a big effect strip movie, right? And it's funny, I for me, it's just another tool in the tool kit. I don't thirst for that. But I know how to, I know how to basically use those tools, and how to communicate with with lighting to you know, lighting, TVs and animators. And so it was like this incredible two year learning curve. That was invaluable.

Alex Ferrari 29:11

I've had I've had a lot of I've had the pleasure of having some amazing guests on my show. And I doesn't cease to amaze me, I can probably count 20 instances that Steven Spielberg launched their careers, or help them along their career. He is one of those, those guiding forces in Hollywood, he doesn't get credit for that he has helped so many filmmakers off the ground, either to start or later in their career or one point. He's always kind of the man behind the curtain in a lot of ways, just giving that nudge helping a little bit out here. And I've heard nothing but the nicest wonderful things about I mean, the craziest stories. It's amazing stories, but and I know He, that's why I knew that he worked with you on Casper. But your story about him doesn't surprise me the least.

Brad Silberling 30:07

Yeah, he it comes out of sheer love of film and filmmaking and storytelling, and it's what keeps the ego out of it. He just wants to push, good work along, you know, a couple of movies mine that that weren't ones that he was involved with. He's just the best like on City of Angels, which I did over at Warner Brothers. He, he said, when's your first preview? Can I come? And I was like, oh, yeah, let's do that. That's gonna freak them out. And so I literally took Stephen to my first you know, audience recruit, they didn't see him. But he wanted to come because he felt so you know, proprietary, and we felt like family. And indeed, like, the studio was freaking out. They're like, Oh, shit. And yet, it was the best because he just had this reaction. And then he's like, Hey, I carved out a day, next week, you know, you want me to? I'll run the picture with you. You want, you know, you want to hear some thoughts. I was like, Yeah, man. He's done that a couple times, three times on movies where he'll come and spend the day just run the picture in the cutting room, again, offer up thoughts. And no, no, you know, no ties to any of those, like, here's what I see. Do with that? What you will, I'm so proud of what you're doing blah, blah, blah. Um, and that's actually what it is.

Alex Ferrari 31:38

And I just heard a story, a friend of mine who released a film. And he's like, dude, do you know I just got a letter from the producer. I just got a call from my producer, who got a letter, a handwritten letter from Stephen saying, Hey, I saw his my film. And I just want to let you know, I really liked it. That was it. Like, there's nothing? No, I don't want to do anything with you. Like I don't want to like, and there's no agenda just like, I saw the movie. I thought you'd like to know that. I liked it.

Brad Silberling 32:09

He's like ahead of the curve. Because what I have found, I think was after City of Angels came out one day, I remember I got a phone call. And I thought it was a friend playing a prank. It was Dustin Hoffman, good cop with only me. And I thought, wow, somebody is doing a really weird Dustin Hoffman imitation is this bread. And he he called me because he'd seen the film. And he really, really enjoyed the movie. And he said, You must like actors. He like actors. I feel like he like actors a lot. And so we talked and I finally said to him, this is so kind of you to do, do do do this. And he said, You know, I didn't for many years. I didn't I was too competitive. He said, But I'm getting a holder. And I like to acknowledge great work. And that was the most incredible thing. And then of course, I took that because then I built him into my next movie. But I Stephen has been ahead of that curve. And I think it is because he, he knows the the pain. You know, people forget his first directing job for him was a nightmare. You know, the the knight gallery, sent him back to Arizona for a year and a half. He was like, I'm not ready to do this. So he knows what it's like to get real support. He knows what it's like to. He always he always says that to me. When I made a film, a film mine moonlight mile, again, was something that I'd written and he's like, it is your DNA. It's you through and true. I feel you in every frame. That is what we're here to do. And so he's it's, it's an incredible thing. And I knows he I know he knows it. But I remind him of yearly I'm like, you know, in Yiddish like what a mitzvah it is you do for your kind every every day you he loves movies, he loves television, he watches everything.

Alex Ferrari 34:18

It's It's remarkable. And the thing I always find fascinating about him is that he's like, he doesn't have to anymore like he had he could have stopped decades ago, you know, after et you could have a lot. He didn't have to do this, but he does it without agenda without quid pro quo. He's just been truly wants to help and wants to and he knows, he knows, in a very humble way that he's the 800 pound gorilla in the room. He he knows that very, very, very well. And he uses that power for good.

Brad Silberling 34:53

Well, and he'll also tell you, which is really funny, I remember between movies at one point he was a was Amblin television or maybe it was DreamWorks Television and they were producing one of their first TV shows. He was like, there all the time. He was like, Hey, come meet me. I'm on the set of so and so out in Chatsworth, come, come hang. And I was like, and I went there. I was like, What are you doing? He's like, Oh, this is like my methadone. He said, If I'm not actually shooting, I need to be really close to it and get a fix. And that is. So he calls he calls, the movies he produces or the TV shows his methadone. And I've always thought of that, because I share that it's my favorite thing. I'm the best director ever. When I go visit a friend set, I got no pressure. I'm really happy with the snacks. The actors look really nice. I'm really just loose. You know,

Alex Ferrari 35:46

Ohh anytime you visit a set, you just like it's not my, it's, I'm just I'm a passenger on this ship. I don't have to I don't have to drive. It's great.

Brad Silberling 35:54

A friend, a friend of mine is starting a movie next week in Boston. I'm going to go visit him. And he said, what day you coming? And I said, I think I'm coming on the blog goes, Oh, that's really funny. That's Guest Director day. That's amazing. So he's like, I'm like, nothing. Doesn't work that way, my friend.

Alex Ferrari 36:13

So one of your, as you mentioned City of Angels, which I absolutely adore. I watch that film every few years because I absolutely adore that film. And it was obviously made a remake of a masterpiece of a film, which is Wings of Desire. How do you approach remaking is really a masterpiece. I'm not exaggerating, winds of desire is a masterpiece.

Brad Silberling 36:37

Oh wins the desire. So you want to go, you want to go on a bad blind date, go see Wings of Desire, which is how I saw that film. I, I went on a blind date. And I went to see wings desire. And I was I couldn't move out of my seat at the end of the movie. And I looked to my left, and the woman that I was there with clearly was looking for her popcorn remnants or whatever it was, and there was like, no response. And I couldn't, there was a really short date after that, you know, it was poetry. And it was just life humor, and observing nuance, and it was an incredible movie. The only way you make that, that film when we did is you you you can't approach it as an actual remake? Because if it were you What are you doing? You know, you can't do it. And so when I got a call about the film, I was really interested, my agent then said, Oh, Dawn, steel. producer Don steel is doing a remake of Wings of Desire. And I was like, what? I couldn't put those elements together, Dawn, who's been gone now. 20 years, was arguably one of the most commercial movie brains as a studio head and then as a producer. So I went into meet her. And what I realized, and I say this lovingly, I don't know if she ever saw the original film. And that's what that's what set me free. I was like, oh, okay, she's thinking of this as a high concept premise. And had engaged Dana Stevens who's a wonderful writer, Dana as well was late to the Dana was not a vendor's efficient auto was not. So they were freed up at the initial stage of development by not chasing that, but by trying to come up with a story. And I knew that for me, if I could bring the emotional response I had to VIMS film and some of the the tonal play, but but also be able to just own it and just think, again, we're not doing because obviously Windsor desires like gossamer threads. It's there's that much story and and the incredible thing is so Nick Cage and I had a real instinct, because I remember asking Dawn steel, I said, So tell me about your conversations with them. What does that been like? And she's like, Oh, I haven't talked to him as a really you've never engaged which goes, Oh, no. Wow. And so when Nick had signed on, he and I both were like, truly loved to get the script to famine, just sort of who knows get any thoughts but more so just reach out and say we want there to be a continuity because we we really are so indebted to the initial impulse he had. And he was amazing. And he read it quickly and responded. And then he ended up becoming like a beautiful kind of godparent to the movie from that point on, or, or an angel, if you will, or an angel, guardian angel, a German guardian angel. He was great. But what he said to me and Nick at that point, which was amazing. He said, This is crazy. Do you know that in my original concept for the movie, it was going to take place in a hospital. And the female lead, of course, who's a trapeze artist was going to be a doctor. He said, My dad was a surgeon. That's where I wanted it to take place. We couldn't afford it. We couldn't afford a location. And we couldn't afford it. That's why I think about it. That's why she's a trapeze artist. We've put a tent up. And we were like, Oh my God, that's the beauty of film. It's like you can't imagine that film any other way. That can, you know, the visual, concede a flight and all that goes and none of that was budget. We couldn't afford it. So again, so vim came to my first test screening with his wife. And they were fantastic because I you know, the way test screenings, good lights come up at the end, you you as the filmmakers Studio, you leave the room. Everybody gets handed their little note cards, and they fill out shit. And Vim and Donati, his wife were really funny because they, nobody knew who he was. So they're like spying on people's cards, and then they would come running out to me, ooh, it's looking really good. And they like this. And they like that. And then he run back in. And so he was awesome through the whole process. But again, didn't expect it to be, you know, a xerox copy, appreciated that we weren't just doing that, but still felt really happy to be connected to the film. And that was the only way i i was able to do it. Otherwise, it would have just been.

Alex Ferrari 42:09

Yeah, cuz you can't, you know, I had John, Panama. I had John Batum on and I talked to him about point in return. I'm like, how do you take the Femme Nikita, and like, redo it like, but he didn't have a guardian angel from France. He was on his own.

Brad Silberling 42:26

John, I know what you're talking about.

Alex Ferrari 42:29

You know, John's, John's that I'd love, John. Absolutely.

Brad Silberling 42:33

And he's and you've seen his book, which he's written, He cares so much about the craft of directing and what directors go through. And he's the best,

Alex Ferrari 42:44

Absolutely no question. Now, how did you How do you approach taking a popular children's series and turning it into a series of unfortunate events? Like how? Because that was at that point in your career, the biggest budget you've ever worked with at that point? Correct?

Brad Silberling 43:02

Yeah, yeah. No, for sure. Cabin Casper and CD of angels were probably within $5 million of each other somewhere in the 60s. And well, yeah, Lemony Snicket by, you know, over two fold, partly because Scott Rudin and Barry Sonnenfeld had been in early development on trying to make the movie at Paramount. And they spent some money. They spent some money, and the studio got very scared because the script it's interesting handler is a friend of mine, and Daniel Handler, who's the real Lemony Snicket. And Daniel had done an adaptation, but the adaptation was like, bonkers. It wasn't, it really wasn't honoring his own work, which amazed me. And I think because he's so prolific and he's so imaginative, I think. He thought, why am I just gonna go recreate what I've done, I want to go do some other stuff. So what I remember asking if I could read where they had been headed, and it was crazy town, but it was also very expensive. So that's how DreamWorks got involved was, they basically decided they were going down the wrong path at Paramount, reached out to DreamWorks to partner on the movie. And it was mutually decided that they would bring on a whole new filmmaking team, new script director. And so I was in Europe. I was with Dustin Hoffman. I was in Europe, promoting moonlight mile when I got a call from Walter parks who was then running DreamWorks under Steven. And he said, Are you familiar with these books? And I said, No. And he said, Go get your hands on them and call me back. And I went to the biggest toy store hat have I think it's called in London and bought the first three books. And was so again, for me it's like, tone, and character. And I was so blown away by, you know, the essential premise of those books, which is that the kids are the adults, the adults are idiots. And that there's a real straight look at darkness that there's a real straight look at loss and perseverance, and what that means. And so I was reading these and just the, again, the sense of wisdom, huge intelligence tone, I just thought was fantastic. So I called him back and I said, this is great, what's the situation? And he said, Well, when you come back, come sit with me and Steven, but if you want to do this, we should do this. And so that began the process, you know that there's 13 books at that point, there weren't 13. But it was decided that we would tackle the first three. But by nature, they are like serials, they're episodic. And my, for me, the biggest challenge was going to be making it still feel like a three act film, and not just like, and then we're here, and then we're here, which some of it is naturally still that way, but that there had to be some sort of a bigger arc. So we spent a good bit of time. And thankfully, handler, was willing to come back into the process because I didn't want to lose his voice. I didn't want to lose his, you know, just I'm sort of sweet and sour thing that he does. And then we had to put Yeah, I mean, it was a very expensive movie, I asked Sherry Lansing, not to make my life harder. But I said to her when I met her, don't you want to, frankly, given the money you're spending? Don't you want to do? It's, you know, expect the future two and three? Don't you want to do two back to back and amortize the cost? These sets are going to be insane amounts. And shares awesome shares like, oh, no, honey, I'm very superstitious. I'm too superstitious. I let the first one come out. And then we'll decide I was like, okay, and I had over the course of early, the you look, you pick up one of those books, there is a sense of there's like a sense of that everything being handmade the illustration. Yeah. And I wanted the film to feel like an illustration. And so when I started scouting, and trying to kind of design the film with Rick Heinrichs, who's awesome, we were actually going out into the real world looking for locate and we both were like, huh, can't do it. This is neither the hunter we have to find a way to make everything feel handmade. It times more two dimensional and three dimensional. That means we have to control it all. That means we're gonna have to be on set the whole time, including for exteriors. And so that's how we approached it. And again, the studio back did but yeah, it was, it was it was an expensive movie,

Alex Ferrari 48:07

It was now how do you direct a force of nature like Jim Carrey? I mean, he's he, I mean, obviously, he's very similar. And energy to Robin Williams, you like this kind of kinetic energy that you just like, you can't control it. All you could do is corral it.

Brad Silberling 48:26

What you do? It would be like if you did a two hour interview, and you hopefully made great prompts, and let that interview go and then sit down together and say, That's salient. That's great. This not so much. What I realized early with Jim Well, two things when people know about Jim Carrey, everything seems like like Robin Williams, like Oh my God. So he is a preparer. And he feels most grounded and safe when he's prepared. So what I realized was like, Okay, how do I do that and still, capture all that's Jim. And what I realized was, I want to basically get the most out of his freedom, and then create. So normally when you do makeup, hair wardrobe tests on a film, there is no sound recorded. You just put an actor up. I had this crazy idea that I got from actually John Slazenger doing this on Midnight Cowboy, which is I brought the sound mixer and I decided to interview each of these potential characters that Jim was going to do meaning. Jim's off and then Jim's Stefano and then Jim is I'd asked him about public policy. I'd asked him about his thoughts on on, you know, secondary education, you know, on Las Vegas, and he just had a great And we're recording it. And we looked at each other after the first day and thought, it's all in there. That's amazing. It's all in there. And so what we did was I went and took from these really, hopefully well prompted, but great improv, I took the best of what we thought could play within the story. Because I did bring it around often to the kids into the situation and what see what he's going to do with the money and Titanic sucked, I could do better. And so what you do is you, you, it's, it's less hemming him in and more like, here's your pasture, let's go play. And I'm going to take your best moves. And we're going to bring that into the story. And so that's what we did, we brought all that material back into the script. So the script, what you have on screen is all material that that derived from improv that we did well ahead of the time. And again, it's like a kid, you know, teenagers with a camera. He and I responded on a really fundamental level, like pals, and I realized that I had to make him feel safe. And, but also, not just pulling surprises, but let's go through let's prepare, he would know, if he had to work the staircase in that mansion. He knew how many steps there were, how many he was going to take before a gesture. And if God forbid, the night before the construction crew change the number of steps. That's where he gets thrown. Because it was like no, I'm so I'm so I'm a dancer, I'm so prepared. And so if you know, that's the animal you're dealing with, you lean into it, and you make him feel safe. The studio got very scared, they got scared off into the process about you know, what the reason kids love those books and why they love the series, because it's super honest, it goes really dark. They get very scared of that at times. And like, the 11th hour, they got a little worried about camera loss makeup. And I said to them, oh, we're past that point. And this is exactly what it's supposed to be. You know, and they, they, but they, I forget what they did. And they they asked Walter parks to see if there was anything he could do. And I was like, Oh, this is not going to end well, because we've committed, it's going to get in his head. And it's gonna blow up. And our first day of shooting, Jim never got on camera. Because I think one of the producers had gotten in his ear like, well, maybe we can have a little less darkness under the eyes. And I remember saying to the producers like that is gonna come at a cost you wait. And sure enough, I went into Jim's trailer and he was like, Wow, are we are we just making a mistake? What's going on? And I said, Absolutely not. You are the character. This is the makeup. Go home today was a great rehearsal for printing from putting on your makeup for three and a half hours. Go home, get some sleep, we're gonna start tomorrow morning. Fuck them. And that's what we did.

Alex Ferrari 53:16

Yeah. And that's, that's awesome. That's an awesome story. Now is there you know, as directors, there's always that day. And it could be at the beginning of your career. It could be at the end of the career. It could be the middle of your career, on a day on the set, when the entire world is coming crashing down around you. And you're like, Oh, my God, like the actor won't come out. Like you were saying before we started like the actors drunk. He's getting she's getting a divorce. We're losing the sunlight. The camera fell on the lake. And every minute that goes by, it's literally 1000s if not hundreds of 1000s of dollars going by. What was that day for you? And how did you overcome that obstacle that day?

Brad Silberling 53:58

Wow. It's so funny because I'm smiling when you're saying that day. It's more like days.

Alex Ferrari 54:05

Every day I asked that question often is like you mean every?

Brad Silberling 54:09

Well, I'll tell you here's a here's a really, I I think I think I'm happy that I don't have a litany of them in my head. Partly because, listen, you the days that you think are going to be a cakewalk slam you like a ton of bricks, right? And then you're like, Holy fuck, how did this get so hard? And then the days that you're anticipating hell become like joyous so it happens throughout the process. I think as you do it more what you know I always say it's a shot at a time. You go one shot at a time I when I would in my golf cart drive myself to set on Lemony Snicket, we shot I think we shot 146 As on that movie, it was 146 days. And I remember, like a third of the way into it thinking this could really become overwhelming. And I remember just driving my cart with my happiest moment was like driving my golf cart to the stage with my little one cup of coffee. And I thought, I think I'm just like a minor, I go into the mine. And I come out with film each day, I can't even begin to think about the end of this journey, because it will take me out, I just have to go in and really concentrate one shot at a time, one performance at a time. And that's how you can persevere and not get overwhelmed. I over the years have gone to sit, just again, my method and I'll go sit with Steven on a set. And it's what's always given me the joy of one shot at a time. Because as much as people like to prepare, he prepares, but he still comes up with it. It's like jazz, he comes up with it a shot at a time on set. And if you do that, you could be shooting 10 days or 100 days and as long as you're getting some sleep and you're eating Okay. And you believe in what you're doing, you can get through it. The one i i I remember one day that was pretty amazing on Lemony Snicket that is about as close to what you're describing, as I've probably ever come. Where we had, we were doing a sequence with Billy Connolly. And there's a character in the books, the incredibly deadly Viper says huge Viper, of course, is harmless, but looks really neat. So we had a giant prosthetic version of the Viper created just to basically be able to rehearse and to for the camera operator scale. And the babies with these were babies who were playing Sunday, they were 14 months old. There were twins when we made the movie, and one of them on the rehearsal in rehearsal, do I always shoot my rehearsal? So everything's always on film, or digital? Because why not? It's like, I'm not going to lose a great performance. So I don't like just a camera rehearsal, I always roll and it gets everybody focused. So we rolled on the rehearsal in the grip who was sort of manipulating this huge, fake snake got a little too overzealous and his performance. And like, what views and the gait of this pen that the snake was in was, you know, fly's open. It goes right at the baby, who's being held by the kids. And she said, it's all it's in the movie. She looks and screams bloody murder. And she's toast. She's like, I'm off. They got to take her off the set, she was scarred. I still feel that she was scarred from that for the rest of the movie. Most of the rest of the movie was her twin sister who was just like a joy baby. She though freaked out. And at that point, when you're dealing with with infants, you only have so many minutes on set. Her sister had already worked that day. I had nowhere else to go. There wasn't another scene we could jump into. There was it was one of those where it was like, and I remember, I just, it was that moment, like, holy shit. I turned to my ad who's done every movie with me. And she's amazing, Michelle than he does. I turned to her with this look. And I said, I need to take a walk. I've never in my career left my set. I never leave the camera. I was so overwhelmed. By this wall. We had walked into that I literally walked out the stage is a paramount. And you know, on a big movie, you've got it feels like 1000 radios all around. There's PDAs. Right? And what I hear on as I'm walking out of the stage and I'm walking down, you know, I hear don't let them get to Melrose don't let them get to Melrose. They literally thought I was gonna walk and never come back. And I don't know if I think about it, but it was amazing. So I got like, halfway down and take a deep breath. You know, like, Okay, again shot at a time. It's their mood I sometimes too, in my head. I think it's their movie too. Meaning I take it all on my head. I take responsibility for everything. But everybody has come together they want to tell this very challenging story with real babies and real this and that. It's their movie too. We'll figure it out. You know, and the more you do it, this friend of mine starting this movie in Boston next week, I was mentioning, a lot of it takes place at a boarding school. He just lost two weeks out his primary location, like incredible Primary School location, all the architecture, because it COVID the Board of Directors, I guess got together and we're like, No, can't do it. And I was on the phone with him when he got the other column, the other line, and he's like, and I checked in with them next morning. He's like, You know what, this is what happens. We do this long enough, we kind of get unflappable. And you do you it's not that you don't care. You just know, there's gonna be a solution. And as always happens in film, you look back and think it couldn't have been any other way. So there's a faith in the process. Yeah. Cast. recasting.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:53

No, you're absolutely right. There's there is that thing that you're like, Oh, why did I lose that? Well, like the trapeze thing. In Wings of Desire. Perfect example. Like, I mean, that he wanted a hospital, but he couldn't afford it. So we got the trapeze. It's, it's, it is such an insanity that we do. I call it the beautiful sickness, because it is. Because it is it is. And you know, which is once you get bitten by that bug, you can't get rid of it ever. It really it's always inside you. And it's beautiful. But it's I've spoken to so many filmmakers over the course of my career, that there's an insanity to what we do. We have we have gone to the circus, we've ran away with the circus.

Brad Silberling 1:01:38

Yeah. And it's a compulsion. Yeah. And there's a and I've had it again since I was younger. So when I was making my little super eight films, lived in a neighborhood that had turned over and really there were not a lot of younger families. There was one kid next door to me, who was younger, was the only actor I had. He was in every movie that I made. And he got really smart. At one point, he started saying, I'm all tired today, like you hold this handout, I have to give them five bucks. And you know, it's my first time dealing with unions. But it was funny because he the compulsion he would look at me some days ago, oh, no, you got another one. Because you just get bitten and you want to tell another story, and you want to go do that thing. And I always say different with different filmmakers, I can look at their movies. Paul Anderson, another fantastic director from the Valley, we are Valley people. Here in LA. I adore licorice pizza. And I looked at it and I said he wanted to make a movie. Meaning he was very excited to create a feeling. It wasn't that he was sitting there chiseling out a story that was just like this. And just like that, he got really excited to go make a movie. And sometimes our movies are that it's like, I want to go make a movie, and I'm gonna find enough that I can care about to hang on this movie. And just enjoy the process. Peter Weir, who among you know, the pantheon of living directors is one of my faves. And I sought him out after Caspar, actually because I was gonna go to Australia. He happened to be in LA and he's become this incredible. Again, friend and mentor. He said a really brilliant thing about he made a movie called greencard with Dr. Jia and, and maybe I missed out. Yeah, that's right. And the movie flopped, and just got kind of panned. And he just had the greatest attitude. And he said of it later, I realized that the audience was in the wrong place. They should have been with us while we were making the movie. Because the process was so pleasurable, we had such a great time. And I guess I wanted them there, maybe less. So sitting in a theater watching the movie, and I, I knew exactly what he meant, which is, you know, sometimes it's just, I want to go and have this great experience. And so, but But it's all from that root compulsion, and part of your job, if people do it with more or less success is how do I manage that compulsion and have a life? You know, for reason that most these marriages go down with filmmakers and other artists. And it's like, you have to find a balance, and we're always working at that. But the bug is still always there. And you know, it's this I call it the great Harrumph. It's this creative Harum for you're unsettled, because you're searching for that next thing to just lock into.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:46

And I'd imagine, you know, being someone like yourself, who's had success as a director in your career, when you start getting those first big jobs, you know, when you're on the set of Casper and on the set of City of Angels and that I guess helps to amplify because the high is so much higher for someone directing, with all the toys in the world like unlimited tickets. That high must be pretty immense for someone like yourself, as opposed to an independent filmmaker who is used to making 100,000 $150,000 movies. Don't get me wrong, it still could be a high for them as well. But I could only imagine the level of flike height you get you get your movies get released, you get huge audiences, you're working with the the best collaborators in the world, you have Steven Spielberg sitting there visiting the set, I could imagine as a director, you that that that compulsion must be even more. So I think that's probably why you do so much television, because television you're constantly working, as opposed to features that take forever.

Brad Silberling 1:05:44

Well, this is this is right. Pilots, and I love making pilots because pilots are little movies that have to be done by May 2. And they have to, they're not going to wait for the actor because they can't they have to have it on their schedule. No, it's true, though. I'll tell you, and I remember this. While I was shooting Casper, Kevin Reynolds who made another thing Waterworld Kevin's an old friend because he married one of my oldest friends. Kevin was on the universal lot. And he got I don't know if he was in post on Waterworld or

Alex Ferrari 1:06:20

95. I think it was in post around that time.

Brad Silberling 1:06:24

And I remember he came by, and I was like, you know, famous at Waterworld, the first movie to ever break the 100 million dollar figure on a budget. And I said, God, that just must be amazing and crazy and great. And champion. And he's looked at me said you know what? It's still all the same problems. He said, I'm still fighting to make my days, I still don't have enough for certain things I want to do. He said so yes, it's great. He said, But don't don't have an illusion that it just suddenly changes. And so when you're talking about the size of the Minister to, I'll tell you where we're all in the same spot in a beautiful way, the first time we walk in with that first audience. We're sitting there if the movie costs $2 million, $200 million, or 20,000, your heart is here, because how are they going to receive this? How are they going to laugh? Are they going to cry? That's the great equalizer. And for me is still what I'm most excited about. It's one thing to sit and just go make a film for myself, but it is an audience experience that I crave. Nothing is better or can be worse, but usually nothing is better. And that's kind of an interesting equalizer. The rest of the sizes, again can be great at times it can be like I say like oh shit, I just got to put on my mining cap because this thing is you know,

Alex Ferrari 1:07:54

Cut cut wood carry water, cut wood carry water, solder to time, carry water. Now I'm going to ask you a few questions asked all of my guests. What advice would you give a filmmaker trying to break into the business today?

Brad Silberling 1:08:08

Okay, so you remember that great line from Glengarry Glen Ross? Always? Closing? Yeah, mine is always be writing. And if you can't write, always be dating a writer. Seriously, because in the end, it is all about content. And for somebody trying to break in somebody's trying to sustain it. So it's the rocky story. It's like Stallone saying yeah, you can make my movie but I'm going to star in it. And the only way for filmmakers to get to guarantee their place unless they're coming off of you know John Watts last movie. The only way you're going to guarantee your place is primacy of and this was Steven has said to me many times too. It's like that's the thing when it's your baby. They mean they don't want to make it but if they make it it's only going to be with you. Always be writing always be dreaming and like I say truly if you're not a writer then find somebody to collaborate with. It's going to be the I mean, I will say without a doubt my most enjoyable experiences be the larger small have been on the films that I've written I've done both and I've loved my other movies too but the experience of it I'm the most free in a weird way. I'm not like I remember Dustin Hoffman on moonlight mile was waiting to see if I was going to be like Mr. Letter perfect. And I was like Oh god no i cuz I I've already written it. Now we can play if we need to play. So but but that it's that it's always in the other thing too. It's like when I was growing up soccer player, you know, we used to watch these Pepsi training films that they would scream and they were always starving. Pele. Pele was always basically dribbling a grapefruit on a beach in Brazil. And his whole thing was, anybody can do this with just a grapefruit. And I think of that all the time, which is if I have that creative, if I to have to wait to pull together $100 million $10 million 200,000 If I have to wait to be creative, because of other people's money, I'm going to be doomed and bitter. And so writing gives me the control there's nothing but keystrokes or a piece of paper or journal. That's gonna stop me from continue. No. And Stephen has a great phrase bill burr he he talks about your your, your your writing I in your directing, I and he has said to me, you know that the reason he knows I love to write is it's, it's my directing I getting to play, but play on the page. So that's, that's the key is I can't stress it enough. Every time I go back to film schools to talk to young people, like you have to be a creator.

Alex Ferrari 1:11:17

Now, what is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film industry or in life?

Brad Silberling 1:11:24

Wow, that's a great question. Um, I would say probably, it's an ongoing lesson. You can begin to wait stubbornness with I guess, integrity and stubbornness for many go hand in hand. And I can be super stubborn when I want to do something, I'm going to get it done. It may take two years, 10 years, it may I'm gonna get it done. And it's funny, I have three movies that I've made, each of which had that about it moonlight mile, I wrote a first draft of in 1993. I made it in 2001 10 items or less similar picture I did with Ben Kingsley, ordinary man, I, by the time things got together, fell apart. So I'm stubborn. But what I realized is that I can't be singular and stubborn meaning be open to I was always at the belief that I have to just stay on one project, I can't be distracted by others. And the challenge there is, that's fine. If you literally are prepared to not go and do something for a long period of time, because there are elements that are out of your control. And so I'm both creatively staunch. But I do, it's like you can juggle more plates in it in a successful and enjoyable way. The more you do it, you get confidence. So I might be developing a limited series that might go. But I'm also out to cast on another movie that it would have been once upon a time, I would have only just sat and waited for that cast come together on that movie, Moonlight mile, and suddenly or the money to come with it. And so suddenly, it was from 2008 to two. But when we released the movie 2000 Or sorry, 98 2002 it was like almost four years. And on the one hand, like Peter Weir always said to me, make sure you live your life. Some people just go movie to movie to movie, you need to take time and read and hike and listen to music and fill yourself. So I'm I'm I have both in me I can wait. But I've learned to not to not cut off other opportunities. And so that initially would have been probably more of a challenge for me and I have a bigger view of it now.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:06

And what is your what are three of your favorite films of all time?

Brad Silberling 1:14:12

I mean, well, every filmmaker will tell you, it's like, don't ask me that question. But I'm gonna tell you obviously, JAWS is what lit my little fuse. i You can ask that question and get a different answer every day. I'm going to tell you I love again talking about Peter. We're in a more commercial film of his. Okay, I'm cheating. I'm giving you two. I love Gallipoli and I love witness witnesses this remarkable movie. It's like this. And then I'm going to give you a only because I recently saw it again and I was like God i wish i have made that movie. I'm going to mention ZhongYi movie that most people have not seen and they must see it. And so it's it's the smallest movie he ever made. It's called not one less. He made it with with non actors and a little Chinese village is the most breathtaking, beautiful. It's like, not even Veritate because it's still beautifully controlled the way he can. But it's what movies can be. I come back to it from time to time to you know, reinvigorate me. I'm a big Ozu fan. Love I love floating weeds. Floating weeds is a movie that I come back to, for tone for just what exactly where that camera is on that 50 millimeter lens. So those are movies that always stay with me. But I do have those movies that I call like, oh, that's just a perfect movie that you can go back to from time to time and they can be indifferent. That can be All the President's Men it can be can be the verdict. It can be you know, you name it. So I have a I have a, you know, one of those revolving CD changers. It's not to fix

Alex Ferrari 1:16:13

Exactly, it's absolutely rotation you got rotation.

Brad Silberling 1:16:16

But it's just it's it's honestly to tweak myself. It's God. That's beauty. Every time I see something that I enjoy, it makes me want to go that day and make a movie. And that's what it is

Alex Ferrari 1:16:29

My friend. I appreciate you coming on the show, Brad. I really do. Thank you so much. It's been a wonderful conversation. I hope it's inspired a few people to go out there and make a movie and and scare the hell out of others to not make movies. But I truly appreciate your time my friend. Please continue making the work that you do and good works. I appreciate you my friend.

Brad Silberling 1:16:48

I appreciate it too. This is fun. Thanks so much.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

LINKS

- Brad Silberling – IMDB

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage– Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible– Get a Free Filmmaking or Screenwriting Audiobook

- Rev.com– $1.25 Closed Captions for Indie Filmmakers – Rev ($10 Off Your First Order)