BOY & BICYCLE (1965)

This being a film journal about contemporary and classic film directors, I often invoke the term “auteur” to describe a filmmaker who brings a singular identity to bear on any given work.

There are many different kinds of auteurs– there are those, like Sofia Coppola or David Fincher, who are revered for a consistent artistic style, while others like Terrence Malick or Paul Thomas Anderson tend to dwell on a variation of the same set of ideological themes over the course of their work. Still others, like celebrated British director Sir Ridley Scott, routinely defy such easy compartmentalization.

Scott’s artistic character isn’t necessarily marked by a recurring set of themes or a specific visual style, although his filmography evidences plenty of examples for both. The projects he takes on suggest more of a journeyman’s attitude to the craft rather than an artistic display of self-expression.

Indeed, Scott is one of the hardest-working filmmakers in the business– 2017 alone will see the release of no less than two of his features, and the man just turned eighty years old. The latter of these features, the upcoming ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD, has been in the news recently because of Scott’s decision to remove Kevin Spacey from the finished film in the wake of the star’s sexual harassment scandal, replacing him with Christopher Plummer with only a scant few weeks to go before the film’s release.

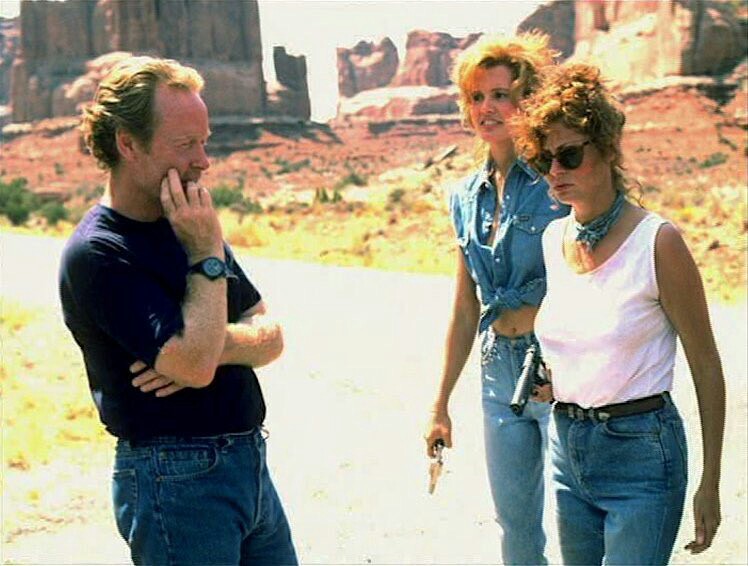

Simply put, Scott is a beast, and his work ethic is unparalleled. The same can be said of his artistic legacy, which encompasses a deep body of work– some of them among the most influential films of all time. ALIEN (1979), BLADE RUNNER (1982), THELMA & LOUISE (1991), GLADIATOR (2000), BLACK HAWK DOWN (2001)…. the list goes on and on.

The three-time Oscar nominee brings a highly visual approach to fully-formed cinematic worlds, each successive film existing within its own contained universe (or sharing an existing universe in the case of his three films in the ALIEN franchise). Even as he enters his eighth decade of life, Scott remains a vital force in contemporary mainstream filmmaking, churning out a new film seemingly year after year with no end in sight.

Scott was born on November 30th, 1937 in South Shields, County Durham, in northeastern England. His father, Colonel Francis Percy Scott, was largely absent throughout much of Ridley’s early childhood due to his being an officer in the Royal Engineers during World War II.

His older brother, Frank, was much older, also unable to serve as a father figure to young Ridley because of his duties to the British Merchant Navy. This left Ridley and his younger brother, Tony, in the sole care of their mother Elizabeth Williams, and many film scholars trace the director’s flair with strong female characters all the way back to her singular influence.

After the war, the Scotts settled along Greens Beck Road in Hartburn– the smoky industrial vistas of which would famously sear themselves into the mind of the young director as a formative influence for BLADE RUNNER’s dystopian vision of Los Angeles circa 2019.

Scott’s interest in filmmaking came about by way of a passion for design, which he formally studied at the West Hartlepool College of Art. After graduating in 1958, he moved to London to attend the Royal College of Art, where he was instrumental in establishing the school’s film department.

1961 saw the production of his very first film, an experimental short called BOY & BICYCLE. The film was initially financed by RCA to the tune of 65 pounds, and shot in the director’s home turf of West Hartlepool as well as Seaton Carew.

An intensely personal work, BOY & BICYCLE features a young Tony Scott in the title role, playing a curious rascal who aimlessly rides his bike through the empty industrial landscapes of the British Steel North Works and pretends he’s the last person on earth. Shot on black and white 16mm film on RCA’s standard-issue Bolex, BOY & BICYCLE’s narrative structure is a natural product of shooting without sound, but it also highlights Scott’s inherent proclivity for pictorial storytelling.

What little dialogue Scott employs was dubbed after the fact, favoring handheld cinema-verite style images strung together by a rambling voiceover delivered by Tony in a thick accent that, admittedly, renders the whole thing nearly unintelligible. BOY & BICYCLE moves along at a brisk clip thanks to the propulsive energy availed by Scott’s shooting handheld and out of the back and sides of a moving vehicle.

John Baker’s music complements the fleet-footed tone, a credit he shares with renowned composer John Barry, who was reportedly so impressed by Scott’s cinematic eye that he recorded a new version of his track, “Onward Christian Spacemen”, for exclusive use in the film.

In shooting the film entirely by himself, Scott’s inherent talent for the medium becomes clear. His later reputation as a visual stylist takes firm root here, boasting compelling compositions and a deft, naturalistic touch with lighting. It’s also fitting that the fascination with world-building that would shape most of his films starts here with the natural world around him.

BOY & BICYCLE’s sense of place is very clear, with nearly every shot composed to favor the moody, polluted landscape or the quaint structures of an old seaside town. While shot in 1961, BOY & BICYCLE wouldn’t actually be finished until 1965, after receiving a 250 pound grant by the British Film Institute’s experimental film fund.

BOY & BICYCLE may not quite resemble the artistic voice that has since become iconic in contemporary cinema, but it is nevertheless a milestone work in Scott’s career, serving as a calling card for the burgeoning young director to launch himself out of the minor leagues of amateur student filmmaking.

TELEVISION WORK (1965-1969)

When we think of feature film directors who successfully made the jump from the television realm, the first person to come to mind is usually Steven Spielberg, who famously broke into the industry when his peers were still laboring through their undergraduate thesis projects.

We think of him as a trailblazer in this regard, but few are aware that he was actually following a path paved by others like director Ridley Scott. Although his stint on the small screen was relatively short, spanning from 1965 to 1969, Scott used this time efficiently and built up a commendable body of TV work that would establish the foundation of his career.

Following his graduation from the Royal College of Art in 1963, Scott found work in the BBC’s Art Department, a gig that indulged and developed the natural inclinations towards design and mise-en-scene that would later form one of the cornerstones of his own directorial aesthetic. 1965 saw the completion of his first film, BOY & BICYCLE, the warm reception to which led to his very first professional credit: directing an episode of the British show, Z CARS, titled “ERROR OF JUDGMENT”.

Scott followed that in 1966 with another show, THIRTY MINUTE THEATRE, shooting an episode called “THE HARD WORD”.

ADAM ADAMANT LIVES! “THE LEAGUE OF UNCHARITABLE LADIES (1966)

Scott’s next third credited gig in the television realm is the only one that’s publicly available, so for our purposes it must serve not just on its own merits, but as a representative sample of his TV directing work as a whole. In 1966, Scott was brought in by producer Verity Lambert to direct an episode of the popular British TV show ADAM ADAMANT LIVES!, in what would be the first of ultimately three entries.

The show features Gerald Harper as the titular Adam Adamant, a secret agent of sorts and a somewhat-prudish relic of the Edwardian era. I say “relic” -literally, as in he became frozen in a block of ice in 1902 and subsequently thawed out into a world he could have never imagined: London during the swinging 60’s.

This seems to be the central conceit of the show, suggesting itself as as key influence for the plot to AUSTIN POWERS: INTERNATIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY (1997).

This first episode, titled “THE LEAGUE OF UNCHARITABLE LADIES”, finds Adamant infiltrating a secret cabal of female assassins masquerading as a club of rich socialites, and subsequently trying to extricate his co-star Julie Harper’s Georgina Jones from their clutches.

The episode’s visual presentation evidences the context of its making– black and white film, presented in the 1.33:1 aspect ratio as appropriate to television’s square screens at the time, and somewhat scrappy production values stemming from what is almost certainly a meager budget.

Scott respects the formalistic conventions of the era, for the most part; this being the 1960’s after all, he’s given ample leeway to bring an expressionistic flair to the proceedings. TV shows of the time weren’t exactly known for their visual finesse, which makes Scott’s work here all the more noteworthy– his restless camera is always on the move, meshing formalist dolly moves with newer, flashier techniques like rack zooms, lens flares, and experimental compositions.

Throughout the episode, Scott evidences a visceral sense of place, shooting from a moving vehicle like he did on BOY & BICYCLE to capture the fleeting rhythms of London’s street life. He also lavishes precious screen-time on setups that are fairly nonconsequential from a plot standpoint, but serve to evoke a mood– case in point, a driving sequence that lingers on the glossy hood of a car as it glows with the neon of passing signage.

It’s safe to say that the disparate elements of Scott’s trademark visual aesthetic have yet to blend together into a cohesive entity, but “THE LEAGUE OF UNCHARITABLE LADIES” shows that they are nevertheless there in a primitive fashion, just waiting to be developed further.

At thirty years old, Scott had established himself as a successful director of television. He’d follow his stint on ADAM ADAMANT LIVES! with two more episodes of the show’s second season, titled “DEATH BEGINS AT SEVENTY” and “THE RESURRECTIONISTS”.

This, naturally, begat more work: an episode for HALF HOUR STORY titled “ROBERT”, and two episodes of THE INFORMER titled “NO FURTHER QUESTIONS” and “YOUR SECRETS ARE SAFE WITH US, MR. LAMBERT”. His final credit in television would go to a 1969 episode of MOGUL titled “IF HE HOLLERS, LET HIM GO”.

While this particular phase of his career was relatively short, it was nonetheless a vital one that established a respectable creative pedigree in the industry– one he’d leverage in 1968 to establish RSA, a commercial production company that remains to this day as one of the most prominent forces in the world of advertising.

HOVIS COMMERCIAL: “BIKE ROUND” (1973)

In 1968, director Ridley Scott co-founded RSA with his younger brother and fellow director, the late Tony Scott. Short for Ridley Scott Associates, the company would grow to become one of the most prominent commercial houses in the advertising industry, claiming some of the most distinguished filmmakers in the world among its roster.

As for Scott himself, he would eventually direct upwards of over 2000 commercials. Naturally, this makes it a unwieldy, near-impossible task to generate a comprehensive analysis of his entire body of work– there sheer volume of Scott’s commercial output is so staggeringly large I couldn’t find anything in the way of even a comprehensive list.

As such, the best course of action appears to be a focus on only his most influential and enduring commercial works, of which there are still many. The earliest of these is a classic spot for Hovis bread, titled “BIKE ROUND”.

Shot in 1973, the spot has gone one to become a beloved piece of British pop culture. The concept is relatively simple, with a nostalgic storyline that finds a young boy having to walk his bike up a long, steep hill every day to buy a loaf of bread, only to have a fun ride back down the hill waiting for him as his reward.

Where the piece stands out is in its stately cinematography, which employs a high-contrast, cinematic touch that favors composition and atmosphere over dialogue. A sense of place is quite palpable here, with Scott’s framing emphasizing the quaint British town that serves as the spot’s backdrop.

The piece feels authentic and well-lived in, and one gets the impression that this very might well be a memory of Scott’s own from somewhere in his childhood. Scott’s aesthetic proves ideally-suited for the commercial space, given his ability to quickly convey an atmosphere and storyline in a visual way that’s both economical and full of detail.

Indeed, one would think he’s been doing this for quite some time. Commercials, by their nature, are transient and impermanent– meant for quick consumption of a timely message and then best forgotten. This is even more true of spots from “BIKE ROUND”’s era, which tended to eschew flashy narrative in favor of utilitarian messaging.

That Scott’s work here has endured after forty-plus years and amidst the noise of veritable millions of subsequent advertisements is all the more remarkable, and points to his future innovations within the format as well as his cinematic legacy at large.

THE DUELLISTS (1977)

I’ll never forget the one time I saw director Ridley Scott in person. Like a frame from one of his movies, it has been seared into my mind. It was the spring of 2008, and I was interning on the Warner Brothers lot. I think I might’ve been on a coffee run for my bosses, or perhaps making my way to the commissary for lunch, and I noticed a large movement of people storming down the New York brownstone section of the backlot.

At the head of the pack was Sir Ridley himself, chomping on a huge cigar as he famously does both on set and in interviews, commanding his aides and colleagues with a militaristic precision. In that moment, he was the very picture of the classical Hollywood director as visionary tyrant– for a young grunt like me, it was akin to seeing General Patton take the battlefield.

I’d be forgiven for thinking that he was simply born this way, having glimpsed him in a moment of his most-realized self in action– it’s very easy to forget that, many decades ago, he too had been the young (ish) man waiting on the sidelines; hungrily searching for his opportunity to prove himself.

Unless you’ve got a famous last name, nobody’s going to simply “give” you the chance to make your film– you have to fight for it at every conceivable juncture, because no one else is going to. Scott learned this lesson the hard way, having spent many years cultivating an impressive body of commercial work that he hoped would attract the eye of Hollywood.

But here he was, already forty years old and responsible for some of the most beloved commercials in British advertising history without having ever made a feature film. We tend to stigmatize commercial directors in relation to Hollywood filmmakers, having been conditioned over the years to regard advertising as a lesser form of moving image.

One can only imagine, then, how much more defined that separation must have been in the 1970’s when Scott– a director with hundreds, if not one-thousand plus commercials to his credit– could only make the jump to features by sheer force of will. After four false starts and unproduced screenplays, Scott finally gained traction with an adaptation of a short story by Joseph Conrad titled “The Duel”.

Not being much of a writer himself, Scott turned to Gerald Vaughan-Jones, a screenwriter whom he had collaborated with twenty years earlier on an unproduced script titled “The Gunpowder Plot”. Together, they fleshed out Conrad’s short story about the decades-long rivalry between two French officers and the contemptuous bond they forge through a series of duels, delivering the blueprint for what would become Scott’s first feature film: THE DUELLISTS (1977).

Despite its aspirations as an opulent and sweeping period piece, THE DUELLISTS is nevertheless a scrappy independent production– indeed, Scott was compelled to forego his own salary in order to make the most of the production’s relatively meager budget. Scott and company shot entirely on location, making full use of the picturesque backdrops and natural, diffused sunlight that surrounded them.

Keith Carradine and Harvey Keitel headline the film as the eponymous duellists, d’Hubert and Feraud. The characters are well-suited towards simmering acrimony: d’Hubert is a rakish aristocrat who seems to effortlessly rise through the ranks by sheer charisma and the grace afforded him by his caste, while Feraud is an intensely stubborn and highly-skilled swordsman from a working class background.

What begins as a minor tiff over d’Hubert’s delivery of bad news from the front grows over the years into a series of encounters driven by Feraud’s obsessive quest to see his humiliated honor satisfied. No matter how much d’Hubert tries to distance himself from this feud and set himself up for a leisurely life in post-Napoleonic France, he can’t help but repeatedly get drawn back into the fray by Feraud, a die-hard Bonapartist who sees his rival’s Royalist inclinations as the stuff of high treason.

Scott stretches his limited budget by focusing almost entirely on his two leads, exaggerating the scope of their interior drama to compensate for the shortage of visual spectacle. However, the decades-spanning narrative provides ample opportunity for supporting performances by actors like Albert Finney, a young & undiscovered Pete Postlethwaite, and Gay Hamilton and Alan Webb of BARRY LYNDON (1975) fame.

Indeed, the influence of Stanley Kubrick’s BARRY LYNDON hangs over the proceedings like a shadow or a spectre– a palpable presence that lingers in the corners of every frame. Similar artistic choices populate both films– lingering zooms, a stately orchestral score, and even an omniscient narrator (played here by American actor Stacy Keach).

This being said, THE DUELLISTS stands on its own merits in regards to its cinematography– a testament more so to Scott’s eye as a visual stylist rather than first-time feature cinematographer Frank Tidy, whose performance Scott reportedly found to be so unsatisfactory that he handled camera operating duties himself for large swaths of the production.

Originating on 35mm film in the 1.85:1, THE DUELLISTS’ cinematography uses BARRY LYNDON’s romantic images as a jumping-off point while infusing a visceral grit that shows the era as the sweaty, bloody, and filthy time that it really was.

Scott’s considered compositions and earthy, tobacco color palette give the picture an identity all its own– one that points to the later hallmarks of Scott’s visual aesthetic with abundant instances of stylish silhouettes, handheld camerawork, blinding lens flares, and soft, romantically-gauzy highlights.

THE DUELLISTS, like BARRY LYNDON, is also notable for its evocative use of natural light, especially in interior sequences that utilize a large key source like a window while foregoing any fill, letting the frame fall beautifully off into absolute darkness. This, of course, is how interiors would have naturally looked at the time, before the magic of electricity cast its widespread glow.

While THE DUELLISTS’ inherent technical scrappiness is a product of its meager budget, Scott nevertheless turns this into an asset that gives his first film a street-level immediacy entirely different from BARRY LYNDON’s birds-eye view.

As a director prized primarily for his aesthetic flourishes, Scott admittedly possesses a limited set of thematic fascinations– only a few of which make an appearance in THE DUELLISTS. The film begins his career-long attraction to the armed forces and the spectacle of battle, a conceit that pops up again and again in films like GI JANE (1997), GLADIATOR (2000), BLACK HAWK DOWN (2001), and KINGDOM OF HEAVEN (2005).

His affection for atmospheric, self-contained worldbuilding, owing to his background as an art director and designer, is by far the most dominant signature at play in THE DUELLISTS, with Scott fleshing out this bygone era with every scene while building to an appropriately-cinematic climax amidst the striking ruins of a castle.

Another aspect of Scott’s artistic signature at play here is his approach to filmmaking as a family affair. He had already been successful in turning his younger brother Tony onto the profession via their joint venture with RSA, and THE DUELLISTS finds Scott installing that same love within his own sons, who were exposed to the craft by virtue of their cameos as d’Hubert’s cherubic children.

Scott’s efforts here very much favor the technical over the thematic, but the result is a remarkably assured debut that would go on to win the award for Best First Film at Cannes in the wake of a glowing critical reception. With the success of THE DUELLISTS, Scott’s career in feature filmmaking was officially off to the races, placing him at the forefront of directors to watch– a position he would cement with his very next feature effort only two years later.

ALIEN (1979)

“In space, nobody can hear you scream”. It’s one of the most iconic taglines in cinema history— an exercise in pulpy brilliance that perfectly encapsulates the movie it accompanies. That movie is, of course, the 1979 science fiction classic ALIEN. ALIEN needs little more introduction than that, having since become the foundation of a high-profile film franchise that actively pumps out new installments to this day (the latest, ALIEN: COVENANT was released in mid-2017).

Both were directed by Sir Ridley Scott, a development notable for its sheer rarity; very few filmmakers would make a return to the franchise they helped create several decades ago… especially one that had been essentially left for dead like the ALIEN franchise had been, withering on life support after a slew of poorly-received sequels.

Of course, ALIEN: COVENANT had more than its fair share of detractors too, but something about the world of ALIEN still beckoned to Scott, long after the initial film’s success kicked his career into overdrive and turned him into one of the biggest filmmakers in the world. He’s returned twice, actually, (2012’s PROMETHEUS endeavored to reboot the franchise with a new spin on its mythology), and is even promising/threatening to make more.

All of this is to say that Scott is clearly fascinated by the cinematic possibilities of the ALIEN universe, and those that might be inclined to cynically ask “why” need only look at the 1979 original: a minimalist suspense picture with a sweeping mythology that ably evokes the unspeakable horrors waiting for us out there in the Great Unknown.

Upon first watch of the film, one might be inclined to ask: “what kind of sick, twisted person would ever dream this up?”. The answer is screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, an eccentric character to say the least. He had been unhappy with his previous stab at the science fiction genre— his screenplay, DARK STAR, had been made as a comedy by director John Carpenter (four years before his own breakout, HALLOWEEN), and notoriously featured a spray-painted beach ball as an antagonistic alien (1).

He longed to combine science fiction with the horror genre, with an otherworldly monster that would actually terrify audiences rather than induce them to laughter. Working in collaboration with Ron Shussett, O’Bannon subsequently reworked the plot and tone of DARK STAR into what would become the first draft of the ALIEN screenplay.

Even at this earliest of stages, the moments that would make the finished film so iconic were already in place— the “truckers in space” attitude of the characters, the horrifying reproduction methods of the alien creature, and, of course, the show-stopping chestburster scene.

While producers found O’Bannon’s screenplay to be of poor quality from a craft perspective, they nevertheless couldn’t deny the horrific power of these moments, and subsequently snapped up the rights in good faith that a proper rewrite would patch up the problem areas.

For quite some time, director Walter Hill was attached to helm the project, but after catching Scott’s THE DUELLISTS in the wake of its impressive debut at the 1977 Cannes Film Festival, he and fellow producers Gordon Carroll & David Giler collectively agreed that Scott had the proper directorial chops to elevate ALIEN beyond its schlocky b-movie trappings.

It’s easy to forget that, despite landmark science fiction works like Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY in 1968 and Andrei Tarkovsky’s SOLARIS in 1972, the genre was regarded rather distastefully by studios in those decades. It wasn’t until the seismic, runaway success of George Lucas’ STAR WARS in 1977 that the tide began to turn.

Anxious to capitalize off audiences’ newfound appreciation for sci-fi, executives at Twentieth Century Fox turned to ALIEN, the only genre-appropriate script they had on their desk at the time. Indeed, the success of STAR WARS can be seen as directly responsible for Fox’s subsequent greenlighting of ALIEN, despite the radical differences in story & tone.

Walter, Carroll & Giler’s gut feelings about Scott’s abilities proved fruitful before production even began, when the director’s detailed storyboards (affectionately referred to by his collaborators as “Ridleygrams”) impressed Fox so much that their initial $4 million budget was doubled.

This anecdote illustrates a key aspect of Scott’s artistic identity, one that is directly responsible for his continued relevancy and success within the industry. The importance of proper prep work before shooting is hammered into the mindsets of all directors, but surprisingly, few actually take the sentiment to heart.

Scott’s productivity and the relatively consistent quality of the product itself is due in no small part to the importance he places on prep and pre-production. One needs only to look at any one of his countless number of signature Ridleygrams to see that the man views prep work as equal to, if not more important than, the work of shooting itself.

STAR WARS may have pioneered the idea of a “worn & dirty” future, but even then its story is concerned with governmental bureaucracies and elite class systems—empires, princesses, Jedi “knights”, and so on. ALIEN endeavors to democratize the realm of science fiction with characters that Middle America can relate to, basing the foundation of its characters off the conceit of “truckers in space”.

As such, the story concerns the small, tight-knit crew of the Nostromo, the space age equivalent of a massive commercial freighter truck, who have just been awakened from cryosleep long before they were scheduled to. The ship’s onboard computer, M.U.T.H.U.R., has detected a distress signal coming from the nearby, unexplored planet of LV-426, and company protocol dictates that any distress signals detected in deep space must be adequately investigated.

Despite their own internal misgivings, the crew, headed up by their even-keel captain, Dallas (played by Tom Skerritt) lands on the windswept, stormy planet and discover the wreckage of a massive alien ship containing a room full of living eggs. This being a horror film too, we know the score— one of the crew members is going to ignore all common sense and get a little too close to those eggs.

This honor befalls executive officer Kane, played memorably by the late, beloved character actor Sir John Hurt. When he tries to get a closer look at one of the eggs, a hideous palm-shaped creature leaps up from it and attaches itself to his face.

The crew members bring the comatose Kane back onboard (with the facehugger still attached) and jet back off into space, where the meat of ALIEN’s story truly lies. Kane eventually wakes up, even feeling perfectly healthy— that is, until a phallus-shaped baby xenomoprh erupts from his chest in a gruesome fountain of blood during an otherwise uneventful dinner.

With the rapidly-growing alien now loose aboard the ship, the crew fights to survive as they’re picked off one by one. The story structure affords each performer their own moment to shine, whether its Harry Dean Stanton’s weary engineer, Brett, Veronica Cartwright’s meek audience-avatar, Lambert, Yaphet Kotto’s money-obsessed chief engineer, Parker, or Ian Holm’s coldly clinical science officer, Ash.

Of course, ALIEN’s true showcase performance lies in Sigourney Weaver, then a relative unknown whose tough, resilient femininity as the now-iconic character of Ripley made her a star. The memorable performances provided by Scott’s cast add significant value to what otherwise could have easily been a schlocky B-movie, with a disposable set of cardboard-cutout characters offered up as sacrifice to a hungry, attention-sucking beast.

THE DUELLISTS established Scott as a supremely gifted visualist, but it’s admittedly easy to make the rolling French countryside, castle ruins, and golden sunlight look beautiful on film. ALIEN possesses a stark, horrific beauty all its own, cementing Scott’s reputation as a visual storyteller even as he endeavors to repulse us with cramped, rundown spaceships and slimy, jet-black extraterrestrials.

Working with cinematographer Derek Vanlint, Scott shoots ALIEN on 35mm film in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio— an expected, conventional choice on its face, but one that becomes rather intriguing when considering that Scott is using a wide aspect ratio typically employed for expansive vistas to frame a claustrophobic labyrinth of corridors and dark corners.

Indeed, the 2.35:1 aspect ratio works counter to its conventional intentions so as to heighten our sense of tension and dread, evoking the Nostromo’s low ceilings by compressing the vertical axis of the frame. Scott and Vanlint give ALIEN a metallic, industrial color palette accentuated by cold tones and grungy textures, while large, impenetrable shadows and silhouettes add a foreboding depth indicative of ALIEN’s aspirations as a work of horror.

An emphasis on atmospheric lighting is one of the hallmarks of Scott’s aesthetic, established in THE DUELLISTS with his evocative use of natural light to portray a pre-industrial, pre-electrified society. ALIEN builds on this aspect of Scott’s artistry by swinging the pendulum in the opposite direction, employing a wide mix of artificial light sources like overhead fluorescents, strobes, halogen lens flares, and even lasers that simultaneously blend and clash; the effect is a frigid, oscillating color temperature that bolsters ALIEN’s striking sense of isolation and remoteness.

Scott’s camerawork favors a mix of objective and subjective perspectives, employing classical dolly moves and pans at the outset only to give way to the controlled chaos of handheld camerawork as the claustrophobic tension mounts.

Having previously served as Scott’s sound editor on THE DUELLISTS, Terry Rawlings returns here as the head of the entire editorial department, reinforcing Vanlint’s probing cinematography with a patient, calculating pace that knows exactly when to draw out the suspense and when to strike with flashes of otherworldly horror.

Having been trained as an art director himself, Scott naturally places the utmost value on his films’ production design (arguably more so than most of his contemporaries). And rightly so— ALIEN’s cinematography and editing, terrifyingly effective as they are, would be nothing without compelling content within the frame itself.

For that reason alone, one can make the argument that Michael Seymour’s Oscar-nominated production design is second only to Scott’s confident direction when taking stock of the film’s legacy. From an art design standpoint, ALIEN hinges on the interplay of industrial and organic textures to better reinforce the clash between Man and Xenomorph.

The “truckers in space” conceit dominates the design of the Nostromo and the crew’s costumes & equipment, conjuring a grimy, utilitarian future where a given vessel’s ability to sustain human life is an afterthought; a distant second to its commercial value.

One need only look at the design of the Nostromo itself, which Scott showcases lovingly throughout the film in lingering shots cleverly framed to imbue huge scale in what is actually an extremely detailed miniature. There’s no sleek or aerodynamic design to the ship— rather, it is bulky and squat, with huge exhaust vents for an engine that no doubts needs to work overtime as it tugs a massive, city-sized refinery complex through deep space.

The interiors of the Nostromo echo the exterior design, featuring a vast underbelly of labyrinthine maintenance tunnels that open up into large, cathedral-like rooms for oversized mechanic equipment, while the ship’s living quarters are cramped, spartan, and colorless.

Naturally, all of this stands in stark contrast to the organic elements at play, which subverts this industrial, spacefaring future with an emphasis on designs that speak to our primal, unconscious need to eat and reproduce. Swiss artist H.R. Giger bears chief responsibility for the overall design of the Xenomorph and its surrounding elements, drawing from his own nightmares to create an iconic alien design that’s simultaneously repulsive yet elegant; even beautiful.

Giger’s work is famous for blending the organic with the industrial, imbuing everything with a weird sexual energy that works on an unconscious level. Indeed, part of what makes the Xenomorph so terrifying to us is how it evokes deeply-seated sexual fears and fascinations: the alien’s head resembles a phallus, while its starships beckon us inside their dark, damp corridors with vaginal portals.

Its reproduction cycle is designed to evoke the horror of rape, in that a facehugger “impregnates” its host by forcefully penetrating it and planting its seed. ALIEN’s focus on primal, organic designs with highly sexual connotations speaks to universal, timeless fears that need no translation or existing phobias to be communicated.

Jerry Goldsmith’s score subtly reinforces ALIEN’s core dynamic, delivering a multi-faceted suite of cues that are at once both lush and unexpectedly romantic in an old-school Hollywood way, yet bolstered by eerie ambient textures that drum up tension. Scott’s subsequent handling of Goldsmith’s score brings validation to some collaborators’ claims that he is difficult to work for— coldly pragmatic at best, tyrannical at worst.

In the wake of the film’s release, Goldsmith criticized the manner in which his work was used, claiming Scott had butchered his score by using several cues from the composer’s prior projects instead of the original tracks he provided. Regardless of the bad blood between them, ALIEN’s score is rightfully celebrated as one of the key aspects of the film’s lasting appeal.

ALIEN establishes a key theme that pops up again throughout Scott’s filmography, especially within his three entries in the franchise: the philosophical quandaries of artificial intelligence. The whole of the Nostromo is governed not by human hands, but by a seemingly omniscient computer system named M.U.T.H.U.R.

By relinquishing control of large swaths of the ship to computational autonomy, the crew is able to focus better on the work at hand— the tradeoff, however, is an increased vulnerability in critical scenarios. The film’s subplot with Ian Holm’s’ Ash character also touches on this topic, with the stunning midpoint revelation that he is actually a sentient android.

Scott cleverly stages the surprise to shock us as much as it does the crew— with Yaphet Kotto bashing Holm’s head clean off, spewing forth a milky substance and mechanical parts instead of blood and viscera. The most experienced member of the cast at the time, Holm sells the deception with a subtle nuance that evidences just how advanced the androids of the ALIEN universe are.

Scott’s overall treatment of the character suggests a wariness, or discerning caution, towards machine sentience; indeed, the whole film serves as something of a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked scientific curiosity, and how easily mankind can unleash something so devastating to its very existence without fully understanding the danger it poses.

As his first big Hollywood film, ALIEN provided Scott with the platform to reach a wide audience and make his name as a feature filmmaker— and reach them he did, if firsthand accounts of people running, screaming, passing out, and barfing are to be believed.

Even smaller reactions, like people moving from the front row to the in order to distance themselves from the screen itself, prove that ALIEN’s efforts to probe mankind’s most unconscious fears and desires was almost too effective.

These stories, of course, are the stuff of box office gold, and the film’s performance suggests a macabre crossover appeal that attracted audiences who weren’t particularly predisposed to sci-fi or horror but nonetheless wanted to take part in the pop culture conversation around it.

It would take time for the critical reviews to match up with the numbers— initial notices were indicative of the genre’s poor regard with critics, but critical appreciation grew steadily over the ensuing years as ALIEN’s timeless qualities emerged. Indeed, the passing of time hasn’t dulled ALIEN’s bite; it’s still as shocking and horrific as it was in 1979.

The Library of Congress inducted the film into its national registry in 2002, deeming ALIEN’s artistic and cultural merits worthy of historical preservation. The following year, Fox collaborated with Scott on the assembly of an alternate “Director’s Cut” of the film.

It should be noted that Scott has always been happy with the 1979 theatrical cut, but agreed to tinker with the film for marketing purposes — and even managed to shave off a minute from the overall runtime, whereas most director’s cuts tend to run longer.

The two cuts are, for all intents and purposes, the same, with the only notable difference being the inclusion of a previously-deleted scene towards the end where Ripley obliges a dying Dallas’ request to finish him off with her blowtorch. Today, ALIEN isn’t just remembered as the foundation of a sprawling pop culture franchise, although it most certainly is— it’s widely regarded as a bonafide classic, an unimpeachable touchstone of both the science fiction and horror genres, and the first salvo in Scott’s campaign to conquer the film industry and remake it in his image.

CHANEL NO. 5 COMMERCIAL: “SHARE THE FANTASY” (1979)

Until the 1979 release of ALIEN elevated him to the realm of major feature film directors, director Sir Ridley Scott had made the commercial segment of the entertainment industry his bread and butter. Of course, now that he had successfully made the leap to Hollywood studio features, his advertising skills were in demand now more than ever.

While he searched for and prepped his follow-up to ALIEN, he used commercial work as opportunities to keep his skills sharp. Of the untold number of spots he may have helmed in the years immediately following ALIEN, one stands as an exemplar of Scott’s craft and ability to shape pop culture– his 1979 spot for Chanel No. 5 titled “SHARE THE FANTASY”.

The piece occupies a comfortable place amongst his most iconic advertising work, having achieved an impact on pop culture whereby those around to see it live on TV remember it fondly and quite vividly. While the spot may seem fairly archaic to those who can only see it as a fuzzy VHS rip on YouTube, “SHARE THE FANTASY” has managed to endure over the subsequent decades as the marketing industry’s equivalent of a golden classic.

The spot finds a beautiful, statuesque woman expounding upon the everlasting quality of her beauty while she watches some random hunky dude swim in her pool. Scott imbues the image with saturated blue and green tones, juxtaposing them against the hot orange of the actors’ skin.

A loaded sexual charge courses through the piece, be it in the symmetrical framing of the pool that’s bisected/penetrated by the shadow of a plane flying overhead, or the deliberate way in which the man emerges from the pool in such a way that he appears to come up from between the woman’s legs.

“SHARE THE FANTASY”’’s heightened, assured visual style is perhaps the clearest indicator of Scott’s touch, but his ability to convey a mood and detailed world in thirty seconds or less gives “SHARE THE FANTASY” its lasting appeal.

BLADE RUNNER (1982)

As I sit here writing this essay, it is the year 2018, in the city of Los Angeles, California. It’s a sunny, slightly chilly morning. When I look out my window, I see the stubby trees, freshly-watered green lawns, and the stately bungalows of Larchmont— a sleepy residential neighborhood just south of Hollywood.

With a few notable exceptions, the surrounding area probably looks just as it did several decades ago, or as it did in 1982— when an ambitious science fiction film named BLADE RUNNER dared to imagine a very different future for Los Angeles. One of the most influential films of all time, BLADE RUNNER is famously set in the year 2019.

Imposing monolithic structures dominate a dark landscape awash in surging neon, soaking acid rain, and flying cars. The tree-lined streets and Craftsman dwellings of my neighborhood have long since been paved over and forgotten about, falling into decay if the structures still even stand at all. We are now just one year removed from the dystopian cyber-punk future that BLADE RUNNER envisioned, and it has thankfully failed to materialize.

However, one needs only drive through the packed streets of Koreatown at night, or look to downtown’s rapidly growing skyline to see that our steady march to a BLADE RUNNER-styled future is all but inevitable. In some ways, my personal journey with director Ridley’s Scott’s iconic masterpiece mirrors its long, hard-fought journey to attain its said-masterpiece status amongst the cinematic community.

In other words, each successive viewing of BLADE RUNNER functioned almost like an archeological dig— with every new pass, another layer of obscuring dirt and grit was stripped away to increasingly reveal the treasure underneath. My very first experience with the film was on a well-worn videocassette borrowed from my high school library, and it was underwhelming, to say the least.

I didn’t really know what I was watching, because the tape was so degraded that the picture was a muddy smear of various browns and blacks. It was enough to put me off the film for several years. I was only able to first see BLADE RUNNER so clearly in 2007, when it received a lavish DVD release complete with a new cut of the film dubbed “The Final Cut”.

In the years since, I’ve revisited BLADE RUNNER several times as each successive home video format brings an added clarity and resolution, with the recent 4K UHD release being nothing short of a full-blown revelation. In the lead-up to the writing of this essay, I devoured everything there is to see on BLADE RUNNER— each of the five official cuts, the sprawling making-of-documentary, Scott’s audio commentary, and the exhaustive supply of bonus content made available on the official multi-disc home video release.

Despite all this however, much of BLADE RUNNER manages to remain elusive— there is always something new to see, some little story bit or profound insight that decides to finally make itself known. This is a large part of BLADE RUNNER’s enduring appeal: for all the mysteries we like to file away as “solved”, there’s untold more just waiting to discovered.

As the 1970’s gave way to the 80’s, Scott was riding high on on the success of his breakout second feature, ALIEN (1979). His inspired blend of sci-fi and horror proved to be an instant classic with audiences, and catapulted him to the forefront of the American studio system.

He quickly attached himself to DUNE, another sci-fi property that styled itself as “STAR WARS for adults”. It was around this time, when Scott was finishing up his sound mix for ALIEN, that a producer named Michael Deeley approached him with the script for BLADE RUNNER, written by Hampton Fancher.

Adapted from the 1968 novel “Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?”, by venerated science fiction author Philip K. Dick, BLADE RUNNER told the story of an ex-cop in the futuristic cityscape of 2019 Los Angeles, tasked with hunting and exterminating illegal, artificially-created humanoids named replicants.

Even Scott had to admit the project sounded interesting, but with DUNE already on his plate, he declined Deeley’s offer. Sometime thereafter, in 1980, Scott’s older brother, Frank, passed away from skin cancer. The loss of his brother sent Scott into a deep, depressed state that compelled him to drop out of directing DUNE— but it also had the curious side effect of opening him up again to the notion of making BLADE RUNNER.

Fancher‘s moody, somber tone must’ve seemed an appropriate match for Scott’s mental state, and upon agreeing to make the film, Scott subsequently enlisted the services of David Peoples to deepen the hard-edged noir grooves of Fancher’s screenplay.

In this light, Scott’s approach to BLADE RUNNER serves as something of a grieving process for his late brother— an intensely personal work that reflects some of the director’s most intimate thoughts & memories; a technical triumph and cultural touchstone that transcends its pulpy genre trappings to become a heartfelt meditation on creation, death & loss— the beauty of life as defined by its ephemerality.

The world of BLADE RUNNER, despite the appeal of its flying cars and fizzy blooms of neon, is a future that humankind very much would like to avoid— in this version of 2019, the world is a polluted wasteland of super dense, cramped urban infrastructure bathed in a perpetual shower of acid rain.

Animals have long since gone extinct, replaced by replicant versions affordable only to the super rich. Like so much dystopian futuristic fiction, Los Angeles has become an omnipresent police state, and many have left Earth entirely to live in the off-world colonies— much like Europeans sailing towards The New World to begin again in what they believe is an untouched paradise.

Bioengineered humans called replicants, or “skinjobs” by those less inclined towards politeness, exist only as a disposable slave workforce— cursed with an extremely limited lifespan of four years. After a violent slave uprising, replicants have been deemed illegal, and specialized bounty hunters called Blade Runners have been commissioned to track them down for early “retirement”.

Amidst this brutal cityscape, the camera finds Rick Deckard: a burned-out ex-cop ripped straight out of the hard boiled-noir tradition (right down to the trench coat). Harrison Ford’s portrayal of Deckard may not have reached the same kind of cultural penetration that Han Solo or Indiana Jones did, but his performance here is iconic nonetheless.

It’s hard to imagine anyone else in the role— even those who the creative team initially considered, like Robert Mitchum (whom Fancher envisioned during his writing) or Dustin Hoffman (who got far enough in casting talks that the storyboards bear his face). Deckard’s long, hard-fought career has made him weary, cynical… even a bit damaged.

On top of all this, he’s dogged by a lingering suspicion that he might just be one and the same with the “skinjobs” he’s hired to exterminate. Like so many retired ex-cops in this genre, Deckard is inevitably pulled back into service by his old boss at the LAPD, tasked with tracking down a dangerous replicant posse headed by Rutger Hauer’s Roy Batty— a combat-model creation looking to break the lock on his expiration date so he can live forever.

Hauer proves an inspired casting choice, with his Aryan looks subtly evoking the eugenic pursuits of the Third Reich, and his channeling of a certain kind of restrained nuttiness (for lack of a better word) resulting in an aura of dangerous unpredictability. His barbed liveliness stands in stark contrast to Deckard’s somber, muted nature; in several instances, one could be forgiven for thinking that Deckard is the artificial one.

Indeed, Batty’s internal awakening to the nature of his own creation, as well as its limits, arguably makes him the most human character in the entire film— a truly sympathetic antagonist who somehow manages to philosophically enrich Deckard’s life even as he attempts to end it.

For all this talk of engineered creation and artificiality, BLADE RUNNER possesses a real, throbbing heart, evidenced in Deckard’s burgeoning romance with Sean Young’s Rachael. Emotionally unavailable in true femme fatale fashion, Rachael is an employee of the Tyrell Corporation as well as an unwitting replicant herself. Hers is a journey of self-discovery; of learning how to become truly alive and fill oneself with passion.

The whole of BLADE RUNNER hinges on Deckard’s relationship to Rachael; together, they are the key to their own emotional salvations. Joe Turkel, perhaps best remembered today as the ghostly bartender with a Cheshire Cat grin in Stanley Kubrick’s THE SHINING (1980), plays the creator of the replicants and the owner of the eponymous Tyrell Corporation.

A meek, frail man saddled with huge coke-bottle glasses, Tyrell lives atop a towering ziggurat, like some kind of Anglo-Aztec god. His is a quiet, determined menace wrought from a perverted sense of parental pride and creative authorship that will be his ultimate undoing.

Daryl Hannah and Edward James Olmos round out Scott’s cast of note: Hannah as Pris, a super-agile and unexpectedly dangerous member of Batty’s skinjob posse, and Olmos as the spiffily-dressed Gaff, a fellow Blade Runner who spouts cryptic messages in a vernacular called “gutter talk”— a mishmash of several disparate languages that point to a hyper-globalized, borderless future.

One of the chief critiques lobbed at the film upon its release was the impression that the human element could be warmer, or more intimate. Indeed, there is a slight degree of remove to the cast’s collective performance— arguably an appropriate choice for a film that explores what it truly means to be human.

BLADE RUNNER’s technical elements, however, are beyond reproach— Scott’s reputation as one of the foremost visual stylists working in cinema today transforms the film into an immersive three-dimensional experience unlike anything audiences had ever seen before. BLADE RUNNER may be classified as a science fiction film, but the conventions and aesthetic concerns of the noir genre inform the visuals at a fundamental level.

The late Jordan Cronenweth is remembered today as a legendary cinematographer, and BLADE RUNNER is a major component of his legacy. The film’s unique aesthetic has become a visual shorthand for a particular style of dystopian futurism, and traces of its DNA can be found in everything from other films, to TV, music videos, video games, and even commercials.

Indeed, it’s become so pervasive in contemporary culture that it’s easy to forget how truly groundbreaking BLADE RUNNER’s unique look was when it first appeared on cinema screens in 1982. The 2.39:1 frame is soaked in the lighting conceits of neo-noir: punchy silhouettes, evocative beams of cold, concentrated light, buzzing blooms of neon color, and a perpetual bath of rain.

Shadows take on a cobalt tinge, further reinforcing the cold future of a nuclear winter, or runaway climate change. Scott and Cronenweth blend formal compositions and camera movements with inspired, experimental visual cues, like the liquid-like shimmering and refracting of light within the cavernous chambers of Tyrell headquarters, or the infamous reflection of a dim red light in the pupils of the replicants (one of the key clues that support the argument of Deckard being an artificial creation himself).

Indeed, the red eye-light is part of a larger visual motif concerning eyes and vision that conveys their psychological significance as “windows into the soul”. One of the very first shots is an extreme close-up of the human eye, every blood vessel visible as it reflects a massive explosion in its pupil.

A manufacturer of synthetic eyes for replicants becomes a crucial source of information for bringing Batty and his posse to Tyrell, and when Tyrell finally meets his fate at their hands, the method of death is the gouging of his eyes until they burst. BLADE RUNNER’s heightened emphasis on the eyes is a particularly salient visual conceit, directly evoking related narrative themes like creation and the existence of a soul, while anticipating psychological concepts that had yet to enter the cultural lexicon like “the uncanny valley”.

Indeed, one of the telltale signs that an otherwise-realistic looking human character is an artificial creation is the lack of an elusively-intangible sense of “life” to the eyes. BLADE RUNNER would come full circle in this regard, with Denis Villeneuve’s 2017 sequel, BLADE RUNNER 2049, digitally recreating a young Rachael that would’ve passed for the real thing if not for the distinct “deadness” in her eyes.

For all its various technical accomplishments, BLADE RUNNER’s production design has easily proven the most resonant in terms of cultural impact. While the contributions of the film’s credited production designer, Lawrence G. Paul, should not be discounted or belittled, his work is still very much in service to Scott’s sprawling vision of a richly layered dystopia.

BLADE RUNNER’s urban industrial hellscape is first seen as an endless field of towering refineries belching massive balls of fire from their stacks— an image that calls back to Scott’s own background amidst a similar environment in England. The Los Angeles of BLADE RUNNER is a hyperdense, over-polluted megalopolis ensconced in a cocoon of perpetual darkness and acid rain.

A distinct Asian character serves as one of the design’s most prescient touches, initially inspired by Scott’s travels in China and his desire to make 2019 LA feel like “Hong Kong on a bad day”.

Indeed, a nighttime drive through LA’s neon-soaked Koreatown neighborhood only reinforces the notion that our contemporary landscape is increasingly resembling BLADE RUNNER’s— a multicultural blend of Mandarin, Japanese, and Korean typographic characters and gigantic video billboards of smiling geishas that have accurately predicted Asia’s rise to world prominence in the wake of globalization.

Scott realizes BLADE RUNNER’s expansive, awe-inspiring vision of Los Angeles through a precise, meticulously-constructed blend of cutting-edge practical effects, miniatures, and models that give the film a visceral tangibility and weight that CGI has yet to completely match.

BLADE RUNNER’s mishmash of incongruous cultural aesthetics extends to the retro futuristic treatment of its interior sets, drawing influence from a sprawling set of ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Aztec design references and blending it with the fantastical urbanism of Fritz Lang’s silent classic, METROPOLIS (1927).

The elegant antiquity of Tyrell’s pyramid-shaped headquarters or the distinct geometric tiling of Deckard’s cramped apartment evidence Scott’s multi-layered, almost four-dimensional design approach; one gets the distinct impression that the 21st century had sustained a revitalized Art Deco movement akin to the 1920’s that flamed out in a brief burst of passion.

For a film that’s so celebrated for a progressive and radically-conceived design approach, BLADE RUNNER nevertheless can’t help being a product of its time.

Scott rightly predicts a world dominated by corporate signage and logos, but the brands that BLADE RUNNER chooses to enshrine in towering neon nevertheless points to the limitations of a contemporaneous perspective: PanAm, Atari, RCA, TDK…. all giants of their respective industries in the early 1980’s, only to see their profiles significantly reduced as we approach 2019 in the real world — that is, if they still even exist at all.

The original score, created by celebrated composer Vangelis fresh off his Oscar win for CHARIOTS OF FIRE (1981), has since gone on to become one of the major cornerstones of BLADE RUNNER’s legacy. The synth sound that has come to define 80’s pop music serves as the foundation for Vangelis’ iconic suite of cues, but Vangelis finds every opportunity to exploit the sound in an avant-garde context.

Majestic synth horns and heavy drums create an otherworldly atmosphere that’s at once both contemplative and foreboding, creating an uncertain future rooted in the musical conventions of the noir genre. One of the score’s most interesting aspects, to my mind, is the inclusion of several pre-existing tracks from Vangelis like “Memories Of Green”.

The romantic, jazzy track uses a live saxophone that stands out by sheer virtue of the analog nature of its recording. The sound is used in conjunction with a piano-based love theme, and appears only in sequences that concern the romance between Deckard and Rachael.

The effect is a subtle, yet evocative, reflection of the film’s internal struggle between the organic and the artificial, as well as a heightening of the idea that love, not the circumstances of their creation, is ultimately what makes them human.

With his third feature film, Scott’s artistic identity begins to exhibit recurring characteristics and thematic preoccupations. One such theme is intelligence and self-awareness in artificial life-forms. The replicants of BLADE RUNNER are not robots, like Ian Holm’s Ash was in ALIEN, but rather bioengineered humans designed with short lifespans for the express purpose of disposable slave labor.

While they are imbued with superhuman abilities like strength or agility, they are viewed by society at large as inferior life forms; less than human. As such, they are oppressed, abused, and persecuted by their creators. When they attempt to rise up and assert their humanity, they are deemed “illegal” on Earth and systematically hunted down for extermination.

Fully aware of their shortened lifespans, the replicants feel emotions with more passion and conviction than their conventionally-birthed counterparts. They are driven by an internal conflict derived from the knowledge that, while their emotions are real, the memories that drive them are not— they are implanted, sourced from a manufactured set of pre-existent memories that delude them with the illusion of a life lived.

They want to break free of this cycle; to live long enough to make their own memories. This is a very heavy, potent idea to explore— especially in the space of a single feature film. As such, Scott explores this theme throughout several films, most notably in his three entries in the ALIEN franchise.

The nature of these explorations within ALIEN and BLADE RUNNER share such similar territory that they have somewhat conjoined into a larger shared universe where the androids of the former grew out of the replicants of the latter.

Indeed, an Easter egg found on the DVD for 2012’s PROMETHEUS establishes a concrete connection wherein Tyrell serves as a mentor to Peter Weyland, who’s name forms one half of the Weyland-Yutani corporation that employs the Nostromo crew in ALIEN (189).

While Scott isn’t necessarily a director known for his stylistic affectations outside of the purely visual, there are nonetheless aspects of his craft that he places an exaggerated emphasis on due to their personal resonance with him. His background as a designer has engineered his directorial eye to favor the architecture of his surrounding environment, be it a pyramid-shaped set on a soundstage or the varying shapes of the real-world urban environment that surrounds him.

BLADE RUNNER uses several real-world locales that were chosen, in large part, because of their architectural and aesthetic value. The film famously uses the symmetrical brick and iron labyrinth that is the Bradbury Building, but other LA design landmarks like the shimmering 2nd Street Tunnel or the stone-tiled Ennis-Brown House in Los Feliz work their way into BLADE RUNNER’s narrative as a striking covered roadway and the exterior of Deckard’s apartment, respectively.

Going back even further into Scott’s development: as a young boy who was raised almost exclusively by his mother for several years while his father was away fighting World War II, he gained an immense appreciation for strong, capable women that is reflected in his art.

BLADE RUNNER is chock full of well-developed women characters who can be tough without sacrificing their femininity: Rachael, Pris, and even the female replicant who hides out from the authorities in plain sight as a snake-charming entertainer all actively drive BLADE RUNNER’s story with their decisions. In a way, these characters are better-realized and developed than even Deckard himself.

Scott’s unflappable, tireless work ethic bears the responsibility for his continued productivity, but it also has earned him a reputation as a hard-ass director with a somewhat tyrannical attitude towards the collaborative aspects of filmmaking.

BLADE RUNNER’s long, famously-grueling shoot established this aspect of Scott’s reputation in earnest, with openly disdainful crew members wearing T-shirts that read “Yes, Guv’nor, My Ass!” and Scott responding in kind with a T-shirt of his own reading “Xenophobia Sucks”.

Indeed, Scott seemed to tangle with nearly every member of his crew and cast— including Ford. It’s admittedly difficult to see the grand sweep of a filmmaker’s vision when one is laboring through the day-to-day logistics of production, and embattled accounts such as the ones that plagued the production of BLADE RUNNER point to just how pioneering that vision truly was.

In every way, at every stage of its development, BLADE RUNNER — as an idea as well as a film — was ahead of its time. We now have the film as a visual landmark to reference, but BLADE RUNNER did not have that luxury because nothing like it had ever existed before.

The film’s mere existence is nothing short of a miracle, with nearly every artistic and financial decision right down to its title having undergone a bitter battle to the death (Fancher’s script went through a seemingly endless series of alternate titles like MECHANISMO and DANGEROUS DAYS before finally arriving at BLADE RUNNER).

At several points, the film came so close to never happening at all: one particular episode saw the filmmakers’ initial source of funding for their $28 million budget pulled away before the shoot, necessitating a last-minute hail-Mary deal orchestrated by Deeley between no less than three separate production entities.

For most films, the theatrical release is the end of the story, but in the case of BLADE RUNNER, the story was only just beginning. One of the most enduring aspects of BLADE RUNNER’s appeal is the aura of mystery that envelopes the film itself, with no less than five officially-released cuts competing for attention.

The initial theatrical cut is dogged by a supremely shitty voiceover by Ford that sounds like he might be drugged— indeed, one account maintains Ford was contractually obligated to deliver the voiceover and actively sabotaged it so it wouldn’t get used (Ford denies this publicly).

This cut also ends with an ill-advised happy ending, which finds Deckard musing about his hopeful future with Rachael as he whisks her away to a rugged, mountainous landscape comprised of unused aerial footage shot for THE SHINING.

The summer of 1982 saw a wave of high-profile films like STAR TREK II, THE THING, and E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL dominate the box office, leaving very little air for a nihilistic sci-fi noir that critics had dragged for its sluggish pacing and hyper-dense intellectualism.

Despite landing with a whimper, BLADE RUNNER nonetheless found an audience, garnering enough critical regard to land Oscar nominations for Best Art Direction and Best Visual Effects that reinforced its reputation as a visual tour de force.

An International Cut containing added moments of graphic violence was also released in 1982, and for many years thereafter, this cut served as the definitive version of BLADE RUNNER on home video (most notably, the Laserdisc put out by the Criterion Collection).

The emerging home video market was arguably BLADE RUNNER’s saving grace, with the ability to rewatch and analyze the film at one’s own pace leading to a small cult following and several passionate academic essays praising the film’s richly-layered visuals and thematic complexity.

Many critics who originally trashed the film would come around later in life, adding BLADE RUNNER to their “best-of” lists for all-time, or at least the 80’s. The BLADE RUNNER “renaissance” wouldn’t truly begin until the early 1990’s, when an alternate cut dubbed “The Workprint” emerged at sneak preview screenings around the country.

The Workprint, initially thought to be Scott’s preferred version of the film, was the first version of BLADE RUNNER to dramatically deviate from what came before— several minutes had been trimmed, the contentious “happy ending” was excised entirely, and the opening titles utilized a different design style that included a definition for replicants attributed to a fictional dictionary published in 2016.

Despite these improvements, the Workprint was still by no means an ideal way of viewing BLADE RUNNER: its status as a so-called “work print” meant that the picture quality was sourced from a rougher, low-quality telecine, possessing a totally different color timing that desaturated the vibrant colors (the blues, especially).

This cut also retained a temp track used during the climactic confrontation between Deckard and Batty, with the cue pulled from another film and clashing dramatically with the character of Vangelis’ score. Needless to say, a perfectionist like Scott was not happy with this “work-in-progress” version being circulated on such a mass scale, so he partnered with Warner Brothers to create an official Director’s Cut in 1992.

This fourth version — one that, when all was said and done, he was still not entirely happy with — was the first to delete Ford’s voiceover entirely, and the first to incorporate the appearance of Deckard’s unicorn dream, which exists to reinforce Scott’s conviction that Deckard himself might be a replicant.

The warm response to this cut finally brought BLADE RUNNER into the mainstream, its nihilistic sentiments now firmly in line with a time where grunge music dominated pop culture and the approaching turn of the millennium invited musings about fantastical, apocalyptic futures.

BLADE RUNNER was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1993, but its influence and importance in pop culture was already well underway. Descendant works like 1999’s THE MATRIX or the 2000 video game PERFECT DARK wore the profound influence of BLADE RUNNER on their sleeves, as do more recent works from this year like Duncan Jones’ MUTE and the Netflix series ALTERED CARBON.

At the same time, BLADE RUNNER also brought the larger body of Philip K. Dick’s literary work to Hollywood’s attention, kickstarting a long series of film adaptations that would make Stephen King slightly green with envy. Naturally, BLADE RUNNER’s resounding influence would come full circle in 2018 with BLADE RUNNER 2049, a sequel executive produced by Scott and directed by emerging auteur Denis Villeneuve that would subsequently meet the same initial box office fate as its predecessor.

The Final Cut, released in 2007 with the film’s debut on the DVD market, further improves on Scott’s ultimate dissatisfaction of the Director’s Cut with minor nips and tucks as well as an improved picture quality thanks to a 4K scan of the original camera negative.

As is par for the course for BLADE RUNNER, the Final Cut ran into big troubles of its own, with the restoration work stalling out a year after its commission in 2001, only to start back up again in 2005. This cut was arguably the most well-received version of BLADE RUNNER, aligning itself more closely to Scott’s initial vision than any previous cut had done.

“The Director’s Cut” is a relatively recent phenomenon in Hollywood filmmaking, having arisen either as a gimmicky marketing tool or a filmmaker’s genuine bid to retain some creative control in a post-auteur climate where the suits prioritize profits over art.

Scott’s filmography is littered with such Director’s Cuts for both reasons, BLADE RUNNER being the first to undergo a recut for the sake of its artistic salvation. This is the beautiful irony of Scott’s legacy: his productivity and no-nonsense work ethic suggest the attitude of a journeyman filmmaker; a gun-for hire.

However, he has been instrumental in establishing the practice of Director’s Cuts as a way for audiences to rediscover “failed” films, and uncover the underlying artistry that they might have missed the first time around. As the various layers of figurative grime have been wiped away from BLADE RUNNER’s iconic frames over the ensuing decades, the picture has increasingly resolved into focus as a portrait of a fully-formed filmmaker operating at the peak of his powers.

For all his later accomplishments in life, Scott will be remembered and cherished primarily because of BLADE RUNNER: a stunning tour-de-force of craft and imagination with a beautifully profound message at the heart of its story. Gaff’s final line has echoed in the back of our heads for nearly forty years: “it’s too bad she won’t live… but then again, who does?”.

This, finally, is the beating heart of Scott’s neon-soaked masterpiece. Our limited time on Earth (replicants doubly so) is what makes life itself so beautiful… and it’s what we do with that time that defines our humanity.

COMMERCIAL & MUSIC VIDEO WORK (1982-1984)

While the 1982 release of director Ridley Scott’s third feature film, BLADE RUNNER, was considered a box office disappointment, it could hardly be called a failure. His next move would be a return to the commercial world that made his name— a capitalization off his surging cultural capital, rather than a retreat to a safe place where he could lick his wounds.

Indeed, the two works readily available from this period — a music video for Roxy Music’s “Avalon” and Apple’s “1984” Super Bowl ad — evidence the artistic growth of a director operating at the peak of his powers.

ROXY MUSIC: “AVALON” (1982)

Scott’s 1982 music video for “AVALON”, off of Roxy Music’s album of the same name, is made notable by virtue of its existence as the director’s only contribution to the music video medium. The track is a lush, downbeat ballad that exudes material luxury, so Scott responds in kind with a series of decadent, sumptuously-shot tableaus of rich people caught up in the thrall of vacant boredom.

From a visual standpoint, the piece is immediately identifiable as Scott’s work, boasting expressive lighting, silhouettes, an ornate and highly-detailed backdrop, and confident camerawork that echoes the luxe mise-en-scene. What’s less identifiable is his intent, as the tone that comes across is downright… creepy.

It’s as if an origin prequel for THE PURGE decided to ape Alain Resnais’ LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD (1961). There’s a quietly unsettling, leering vibe to the whole thing— whatever the opposite of a voyeuristic experience is — and the more I think about it, the more I grow to like the concept of it.

The somber, bored rich people grow increasingly aware of our presence, looking at us directly with stares that feel exponentially confrontational… or maybe I’m just reading into it a little too much. There’s also an owl thrown in there for good measure, which seems to serve little purpose other than nodding back to BLADE RUNNER.

Scott’s only music video injects a nuanced complexity into an otherwise simplistic 80’s hit, becoming something of a comment on the song itself rather than a visual echo of its lyrics or style.

APPLE: “1984” (1984)

At the risk of laying down some hot takes, there’s a strong argument to be made that Scott’s commercial career is even more successful than his filmography of theatrical features. If one were to make such an argument, Exhibit A would undoubtedly be his 1984 spot for Apple, which has since gone on to become one of the most influential, recognizable and iconic commercials of all time.

The spot that introduced the Apple Macintosh computer to the world, “1984” paints a vivid picture of a dystopian future ruled over by a looming dictator seen only on a giant television screen while legions of identical followers obediently watch his fiery, droning speech.

Into this picture storms a virile Olympian who flings a giant sledgehammer into the screen, destroying the dictator’s face and freeing his followers from their hypnotic spell. The expressive lighting and highly-detailed production design point to Scott’s signature, while establishing the template for future commercial directors like David Fincher to follow.

Scott’s affection for strong heroines gives “1984” an added resonance— on a surface level, she stands out by virtue of being a vibrant, muscular and confidant woman in a sea of pale, atrophied, faceless men. Her presence also points to a further sprawl of complex ideas, like democracy (as embodied by an Amazonian Lady Liberty) laying waste to fascism, or the sophistication of the feminine form reinforcing the evolved design ethos that would make Apple a computing giant.

That Scott is able to convey so much thematic subtext and world building in a mere 60 seconds is a testament to his innate understanding of the medium and his staggering power as a visual storyteller.

It sees strange, or perhaps even disingenuous, to talk of marketing campaigns as cultural touchstones, but truly inspired advertising has the ability to transcend its commercial, capitalistic ambitions and become Art. Scott’s “1984” spot is one of the rare few to resonate at this level, cementing itself as arguably the zenith of the director’s commercial filmography.

LEGEND (1985)

Given director Ridley Scott’s English background and his affection for highly-detailed and richly-developed world building, it was perhaps only a matter of time until he tackled the fantasy genre. He would achieve such a feat with 1985’s LEGEND, his fourth feature film.

Released three years after the somewhat disappointing reception of BLADE RUNNER (1982), LEGEND’s genre trappings had beckoned to Scott ever since the production of his first feature, THE DUELLISTS (1977), where he conceived of an idea to do a cinematic adaptation of “Tristan & Isolde” (2).

That particular project fell apart after a brief development period, but through the ensuing years, he still nonetheless harbored a desire to make what he described as a “lean” fantasy picture— one that “didn’t get bogged down in too classical a format”.

In other words, he wished to apply the visual grammar of 80’s pop cinema to a genre usually regarded for its regal formalism and swashbuckling adventure. Before he commenced production on BLADE RUNNER, Scott worked for five weeks with screenwriter William Hjortsberg, hammering out over fifteen drafts of a screenplay while referencing Disney’s classic animated films SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS (1937), FANTASIA (1940), & PINOCCHIO (1940), as well as Jean Cocteau’s BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (1946) (3). Once the arduous shoot for BLADE RUNNER was over, Scott turned his attention to actively producing LEGEND, working with producer Arnon Milchan on a budget of $24.5 million.

The final product would prove divisive, becoming the first real failure of Scott’s feature career for a time before finding critical reappraisal in the wake of a Director’s Cut release decades later. For all the detail and attention he lavishes on its presentation, Scott doesn’t necessarily divulge a lot of information about the world of LEGEND.

We don’t even know the land’s name — we just know that it a lush, forested paradise where magical unicorns run free (an image that retroactively reminds one of a similar appearance in Scott’s Director’s Cut of BLADE RUNNER some years later). We’re quickly introduced to a beautiful, virginal princess named Lili (played by Mia Sara), whose naive innocence begets a kind of stubborn greediness that kickstarts the story.

When she’s told by her friend, a Peter-Pan-like forest boy/creature named Jack (played by a baby-faced Tom Cruise), that she mustn’t touch the sacred unicorns —that no human has ever dared to make contact with the magical horned horse — she goes ahead and does it anyway.

Jack is the protector of this forest realm, which includes a guardianship over these rare unicorns — indeed, there’s only two left in the entire world, and their horns are regarded by some as a treasure onto themselves. Jack and Lili are unaware that said treasure is being aggressively sought after by none other than Darkness, the incarnation of earthly evil who rules over a massive, foreboding palace shrouded in perpetual shadow.

Tim Curry, nearly unrecognizable under pounds of heavy prosthetic makeup that reportedly took 5 ½ hours to apply every day, delivers one of the genre’s most iconic performances by relishing in his devilish character’s seductive charisma.

During a moment of weakness for Jack, which finds him forsaking his duty to dive for a ring that Lili has dropped into the lake, Darkness’ goblin lackeys strike— hacking off one of the unicorns’ horns and subsequently plunging this idyllic, sunny paradise into a dark, icy winter.

It’s only a matter of time until Lili and the last unicorn are captured, prompting Jack to team up with a band of dwarves led by a Puck-style nymph/boy thing named Gump (David Bennent) and venture forth into Darkness’ lair to quite literally deliver them from Evil incarnate.

LEGEND retains the expressive cinematography that’s hereto marked Scott’s filmography— a blend of atmospheric lighting, silhouettes, dynamic camerawork, and bright, saturated color. Having originally wanted to shoot on large format 70mm, Scott and cinematographer Alex Thomson settle for the standard 35mm gauge in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio.

The film’s fantastical theatricality affords Scott to further push the bounds of his aesthetic, evidenced in stylish flourishes like large shafts of concentrated light, impressionistic slow-motion, and even the use of black-light FX on Darkness’ makeup during the Theatrical Cut’s opening sequence.