Mark W. Travis acclaimed as “the director’s director”, Mark W. Travis is regarded by many Hollywood and International professionals as one of the world’s leading authorities in the art and craft of film directing. Drawing from his impressive background in design, writing, acting, and his wide range of experience directing theater, film and television, Mark is able to bring new insights and exceptional clarity to the complex task of directing the feature film.

Mark W. Travis earned a B.A. degree in Theatre at Antioch College and did his graduate training in Directing in the MFA program at the Yale School of Drama. Mark is a creative consultant to film directors Mark Rydell, George Tillman, Cyrus Nowrasteh and many other notable writers and directors.

Mark’s television directing credits include The Facts of Life, Family Ties, Capitol and the Emmy Award-winning PBS dramatic special, Blind Tom: The Thomas Bethune Story. In 1998 he directed the pilot for LifeStories.

In 1990 he completed his first film, Going Under, for Warner Bros., starring Bill Pullman and Ned Beatty. In 2001 he wrote and directed The Baritones (parody of The Sopranos) as well as the short documentary, Earlet. In 2006 he co-directed the documentary, Ancient Light.

Mark’s unique approach to working with actors and characters (The Travis Technique) has gained the attention of directors, writers and actors worldwide and is becoming a standard approach for stimulating powerful performances.

Since 1992 Mark has been sharing his techniques on writing, acting and directing worldwide.

- USA: The Directors Guild, American Film Institute, Pixar Animations Studios, UCLA Extension, Taos Talking Pictures Film Festival, Denver Film Festival, Hollywood Actor’s Workshop, Hollywood Film Institute.

- JAPAN: Film & Media Lab and Vantan Film School.

- GERMANY: UW Filmseminares, ActionConcept, IFS, and HFF, the Munich Film School.

- POLAND: The Film Farm in Kotla.

- ENGLAND: Raindance, Paradigm Film Productions, Hurtwood House, Metropolitan Film School, National Film and Television School, London Film School, Lionhead Studios, London Film Academy.

- FRANCE: The Cannes Film Festival,

- NETHERLANDS: The Maurits Binger Institute.

- UKRAINE: HSU in Kiev, OIFF in Odessa;

- RUSSIA: International Film Actors Workshop,

- IRELAND: FAS Screen Training Ireland,

- NORWAY: The Norwegian Film School,

- DENMARK: The National Film School ofDenmark,

- SPAIN: afilm International Film Workshops,

- CZECH REPUBLIC: FAMU Academy of Film and Television.

Mark has served as a Creative Consultant on several feature films including: Here’s Herbie; Notorious; Not Forgotten; The Stoning of Soraya M,; Black Irish; Men of Honor; Barbershop; Barbershop 2; The Day Reagan Was Shot; Norma Jean, Jack and Me and television episodes of: Lois and Clark; The Pretender; Picket Fences, 90210, Melrose Place; Strong Medicine; NYPD Blue; The Practice and Ally MacBeal.

Mark is the author of the Number-One Best Seller (L.A. Times), THE DIRECTOR’S JOURNEY: the Creative Collaboration between Directors, Writers and Actors. His second book on directing, DIRECTING FEATURE FILMS (published in April of 2002) is currently used as required text in film schools worldwide. His next book, THE FILM DIRECTOR’S BAG OF TRICKS will be published in September 2011.

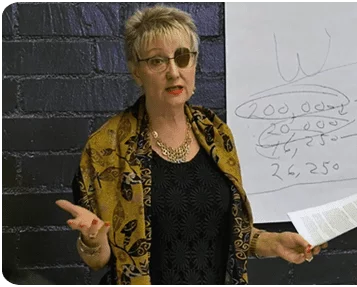

Please enjoy my conversation with Mark Travis.

Mark Travis 0:00

But if I staged her to a point of comfort and I asked for discomfort now she's getting mixed messages. And quite honestly, Alex, the actress may not know that she's getting mixed messages. She just knows she has to do one thing at that moment. She's feeling comfortable. I'm asking for discomfort. She's gonna have to do something you don't want. She's gonna have to act.

Alex Ferrari 0:23

This episode is brought to you by the Best Selling Book Rise of the Filmtrepreneur how to turn your independent film into a money making business. Learn more at filmbizbook.com. I like to welcome back to the show returning champion Mark Travis.

Mark Travis 0:40

I'm totally great. I didn't expect returning champion.

Alex Ferrari 0:45

You were in episode 154. Very well, a variable received episode over the years how to direct the character not the actor, which was your The Travis Technique and all that stuff. And it was a fantastic conversation. We it's almost two hours if I remember. It was a long conversation about that. And because it was just a unique way of a director approaching raft, it was just completely different. But it's been a while you're you're due back, sir. You're you're you're late, you should have been back years ago. But but in this episode, we're really going to focus on another area that you're really trying to change the game and as well as staging. So before we get into staging, can you tell everybody a little bit about yourself, where you come from how you got into the business?

Mark Travis 1:37

Yeah, first of all, I'm a director, writer, actor, and all that in this business, how I got into this business, which is really important. And anything we're discussing is, I came into this world through theater. And it was when I was in college, I discovered theater and something clicked. And I started working a lot in theater, and studying theater. And I went to Yale Drama School to study as a director in the MFA program. And that's how I got into this business. And then somehow, I ended up in Los Angeles and started studying film. The reason I mentioned the theater part is because my career has done a very, all by itself, an interesting shift, which I was not expecting many years ago, I was directing, I was directing television, I directed my first feature film, which did not do well. And there was for a major studio known as Warner Brothers. And we could talk about that and why not to do what I did. But then if you know, we're your first film with a major studio, if it doesn't do well, boy, you you have a big albatross on your back anyway. That but that led me to where I am now into teaching, ironically. And what I discovered is everything I've learned everything I know all the skills I've acquired. My teaching, has done two things. First of all, it has given me a whole nother projected in terms of the work I'm doing, teaching, consulting, coaching, and all that. But the important thing about teaching anything, but especially a craft like filmmaking, is you'll get questions like, Why did you do it this way? Or how do you do this? Or why do you do that? And you have to come up with an answer. Now the thing is, most of what we do as directors, or so much of what we do is by instinct, intuition. I'm gonna put the camera here, I'm gonna direct it this way. No, I want it on this location. But if someone asks you a why, to explain to me why you're making that choice in terms of your film, you really have to think about what you have to do as a teacher is look at what you're doing, and try to understand what you're doing, and then be able to explain it to somebody else in such a way that they can understand not necessarily that they have to do that, but they can understand why you're making those choices. So in terms of the staging, which we'll talk about today, staging and terms of storytelling is a very, very important aspect of it, whether it's theatre or film, but we'll talk about theater for a second here or more. In theater, it's all you've got. You've got the play, you've got the cast, you've got the set, you've got the lights, you've got all that staging is your most powerful tool and you have to stage the place somehow. You have to do something, what you don't have a lot of things you don't have in theater. You don't have a camera, you don't have multiple takes. You don't have editing, you don't have all those tools that we have and rely heavily on in filmmaking. So staging has to work and you have to learn in theater, which I did and still I still direct theater. How can I focus The audience the way I want them to be, how can I highlight something? How can I stimulate the actors? How can I use this tool, I have to use this tool, the stage to make the play work. So that's suicide when I started teaching, film directing. And once again, we're looking at a scene and many times, I'd look at a scene that a student would bring in, and I'd say, Okay, this is good. But you know, the staging is off. Let me show you something. And I would show them something, they say, How did you do that? Suddenly, the scene would change. Now I have to figure out why. After years of directing why I'm making that choice, and how does it come to me. So this is a serious part of my work now, in my work now to, which we haven't discussed yet, Alex, but I will happy to is, I am trying to be very clearly in these coming years, I focus on a couple of things, one, understand what I do and why I do it, and how it works and why it works. And the other is, and that's why I'm doing podcasts, and a lot of online teaching, is to record all of it. So it's there. It's a legacy project. So I can say, I have recorded this, I've stopped writing books, because I can't write a book well enough, that you can see what I'm doing. But I can record something, I can record a video I can. And so now a lot of my teaching, I'm using a lot of video and a lot of film clips. So you can actually see the process and see the change, you have to see it, you can't just read about it. So that's where I am now. And I'm doing a lot of online seminars, workshops. I'm in the middle of one now, which is on staging, ironically, and which we'll finish up next week. I'm doing those in order for me to continue to do this exploration, and then share all the ideas with other filmmakers around the world.

Alex Ferrari 7:02

Fantastic. I've always been fascinated with your teaching technique and what you've been doing. But since you brought it up, I need to go back and ask your first feature or a feature that you did with Warner's going under? I'm not mistaken.

Mark Travis 7:19

And that's what it did.

Alex Ferrari 7:21

Went straight down to the bottom. But I mean, the cast I mean, you had Bill Pullman, you had net, and a bunch of other cast cast the character.

Mark Travis 7:33

Roddy McDowell doing an impression of Mr. Rogers in the film. I bet no, I had some amazing actors.

Alex Ferrari 7:43

So with so when you when you went through that process, and this I always love it, I love digging into these kind of conversations in the stories, because filmmakers don't understand. And yeah, it was the 90s. And it's a different world than it was today and things like that. But a lot of the core lessons are still there. So right when they're you made your movie didn't do well. The town threw you into directors jail, basically, if that's that's generally what happens, right?

Mark Travis 8:09

Especially, what happens is the budget of this, by the way, it was wrong. 9 million, which to them was pocket change.

Alex Ferrari 8:17

So that's like an equivalent of maybe a 50 or $60 million studio movie today. Not dollar wise, but scope wise of what you

Mark Travis 8:26

Scope wise. Yes. And it's one of those a little bit about that we we myself and the two writers. We're seeking to make it for 3 million independently. And Warner Brothers got interested in as a lot of that's a long story, which has something to do with Bronx Tale of why they were interested because I create A Bronx Tale anyway. And so they wanted to talk to me, but as soon as the student they took it over as a independent project that they were just going to do a negative pickup on. And then they decided they Warner Brothers decided to produce it. They said no, no, it's not going to be a negative. And that's when it went from 3 million suddenly to 9 million. And getting back to what you're talking about. Did anything change? No, it just got more expensive. And all the vendors that we had already lined up to work on this project. Suddenly their prices went up when it said Warner Brothers shot and I got I got more money, but I can't do anymore. I can't do more with it. But I got more money to spend but but that's it. So so what happened was it exploded financially. And it also exploded in terms of studio control.

Alex Ferrari 9:46

And that's it. Yeah, the studio at the same time. Start to crawl up your butt.

Mark Travis 9:50

Yep, absolutely. And there were a lot of other stories If you want to talk about them later. I can. It's a long painful, beautiful but painful story. Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 9:59

So Yeah, and it's just a classic tale of what happens in the studio system. Unless you're a big hitter, and you can, you're the 800 pound gorilla. Or you can walk around with Scott and do whatever the hell you want a different conversation when it's your first time out, and you got to chat.

Mark Travis 10:17

Now one little thing, I'll make this short. Bob Daley, who is head of Warner Brothers at the time, and when the film was finished, and he wanted to meet with me, and we had a very nice meeting. And I'm not going to get into all of this right now. But the internal politics of a major studio, once they are producing your film, you're, you're part of that. And you're part of, and you get into the competition between executives between them that it's like the world's most dysfunctional family. And all Bob Daley could say to me afterwards, he says, I'm sorry, Mark, you're just at the wrong place at the wrong time. Had nothing to do with the film, the quality of the film it had to do with the internal politics that was going on the wars that were going on.

Alex Ferrari 11:04

And I can only imagine what's going on at Warner Brothers again with that girl, they just shelled the 100 million dollar finished film.

Mark Travis 11:14

I know. Extraordinary. That Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 11:17

I mean, they'll dump it on HBO Max. I mean, how bad they've released Catwoman like what? How bad is bad girl that they just so you know, the politics? You know, how many people lost their jobs during that, that there's so much stuff going on?

Mark Travis 11:34

It's the walls effect if they really if they released it now, even just streaming? Do you know how many people would want to see Oh, my God, how bad is this really?

Alex Ferrari 11:44

Was like cats. I mean, cats was so bad. Yeah, that it's the worst thing to happen to cats and dogs. But my favorite line, your favorite. That's great. I'm right. That was good. It was a Twitter review. I was like, oh my god, that is amazing. I stopped 20 minutes in I couldn't I just couldn't go any farther. And that would be so so bad. But I got to start to watch it. And the only reason I wanted to watch it was how bad is this? Yeah.

Mark Travis 12:13

And you found out? And that's good. So it was what you expected or worse anyway, but that's

Alex Ferrari 12:20

And that's the thing too, with bad girl is that you're right. If there's a reason why it's not being released, and it's politics, Internal. Internal politics is the only reason why it's not getting released. Because there's value there. Even if it's a bet look, Warner Brothers puts out bad movies. They've put out a ton of bad movies in the in the history of Warner Brothers. Yeah, what made this one so special of how bad is it? It's insane. But anyway, that just wanted to kind of go go wander with you again, take you back to the some of the worst times of your life and really relive them, sir.

Mark Travis 12:52

Yes, thank you. Thank you. So it got so bad I ended up in the hospital. So there.

Alex Ferrari 13:00

I know many directors. I've had panic attacks on set. Oh, it's it's not it's not a fun. It's not an easy job. Now, there's a question I wanted to ask you. You've talked about the four languages of cinema, what are the four languages of cinema?

Mark Travis 13:15

Four languages. Well, first of all, there is the visual language, which we which is a whole nother subject, which is huge, because it's a visual medium. So is that visual, and when I say language is that we you as the filmmaker are actually communicating with your audience through these four languages. So what one is the visual however you shoot it, the looks, the production design, the aesthetics, the CGI, whatever it is, there's that visual language. The second language is very clearly the dialogue which is a language that's usually in English, whatever, but that dialogue and how in the script and how in the final film, you're using dialogue, how dialogue is communicating with the audience, and all four languages are communicating the the audience simultaneously. The third language is sound, aside from dialogue, but a sound sound effects music, and however you're using the element of audio and sound to tell your story. Now, the fourth one, which I've never heard anybody else talk about this, but this is this is me, this is my way look at the fourth one is staging. Because and this is why staging, I talked about the Power of Staging staging is way more powerful than most people really understand. Because of some very basic things now staging just to define it or blocking whatever you want to call it. Blocking is more of a theater term staging is more of a film term doesn't matter. It's pretty much the same thing. I'm telling Talking about the movement of the characters in the space and the environment that are in, I'm talking about characters in relationship moving in relationship to each other. I'm talking about relationship to the room or the space, and even very specifically, very powerfully, a character's movement in relationship to him or herself, which is very simply body language body line. Now, all of these movements, communicate with the audience. If you have two people talking to each other, for instance, like this, and one turns away from the other, that staging, because we look at that, and we go, oh, what's going on? Something's going on. So even the most minut things, even if you get into really micro staging, it can be a look, a look at that character. Now, maybe this is choice of this look, from one character to another was made in post production, but that staging is communication, it is a language. Now there are two things about staging that are really essential, and from my perspective, and my experience is I can take two actors in a room, say in an office, and they're doing a scene, they say it's an interview scene, and someone's interviewing for a job or something like that. And I know that with these two people, I have two people. And I have a space, which is just an office, there's nothing really extraordinary about the office, it's fine, it belongs to one guy, and not to the young woman will say it's the boss and the young woman. But I know as I move these two, I just want to talk about the actors. Now forget the characters for a moment. Where I start the scene, if I start that office interview with the boss sitting behind his desk, and she walks in, and I walk and I stage it I say walk in, I walk her into a space, where she is not near any furniture, she has no support as I stopped there. I just know that move will affect her the actress emotionally, she will feel unsupported, she'll feel insecure something. If I walk her in and have her sit on a chair in front of his desk, she'll have another emotional experience automatically. Now, the wonderful thing about actors really good actors is they will allow themselves to be open to whatever the staging is doing to them. So I can stage these two actors in a way to trigger emotions in both actors.

If I start out the scene, she's going to walk in, but he's at the window looking out of the window, she's going to have a different emotional reaction when she sees him. And he'll feel differently, I can put him in positions of power, I can put him in positions where he'll lose power, all of that. So in other words, staging, when you're staging actors. Remember, it's not just about the way it looks on the set, or the way it looks on camera. And for the moment, I would say, forget the cameras for a moment, you got to make it work organically with these actors. That's when you're staging remember that you are triggering, no matter what you do, anything you do, it's triggering an emotion within the actor. And what you want to do is triggered the emotion that the actor needs for the character. If if you say to that young woman coming in for the interview, if you bring her in and sit her down in a chair in a nice chair in front of the office, and you say to her, how do you feel she says, Great, this is good. Now she's comfortable. And then you say to her, Okay, let's do the same. Remember, you're really uncomfortable. While you now you're at cross purposes, your staging has said, Be comfortable. Your direction has said be uncomfortable. It's better to put her in a place where she's uncomfortable.

And in fact, when I'm staging something, if I'm staging this young woman, I say I come in here, just stand here. How do you feel what standing here away from all this furniture and this sort of no man zone, and she's, this doesn't feel good, I'll say good. And many times the actual go Got it. Got it. In other words, they understand this is an important part of staging. I can communicate with an actor what I want from the actor, just by the way, I staged them. But if I staged her to a point of comfort, and I asked for discomfort, now she's getting mixed messages. And quite honestly, Alex, the actress may not know that she's getting mixed messages. She just knows she has to do one thing at that moment. She's feeling comfortable. I'm asking her discomfort. She's going to have to do something you don't want. She's going to have to act. She's gonna have to, she's gonna have to pretend to be uncomfortable, find discomfort, go through a sense memory, whatever she's going to have to do. I'm trying to avoid that kind of acting, which you know from my run During the view about work directing the the character rather than the actor, that I don't want her to act. The what's really clear to me about characters and emotional states is that all of us are characters in our lives. And you and I are Alex right now, whatever with whatever's going on. And what we deal with as we go through our lives is we get hit by a lot of stimuli, we get hit by thoughts, we get hit by what we see what we hear what we taste, and we go, and we have emotional reactions, we see somebody that we didn't want to see and hope never to see you again. And suddenly we're upset or angry or afraid. In other words, all this stimuli comes. And this also stimuli from within us our thoughts, our patterns. So we go through life having a emotional reactions to our daily existence. And what we do is we deal with those emotional reactions as best as we can. When you see that person, then suddenly, you know, it's all It feels very romantic, you go, Oh, my God, she's so gorgeous, you try to deal with that the best that you may be, you try to hold on to that. That's what we do, we do not go through life very important, trying to stimulate emotional reactions. So when you say to the actress who's very comfortable, I want you to be uncomfortable. Remember, you're very uncomfortable. Now she's gonna have to stimulate something that she's genuinely not feeling at all. So there's this huge disconnect. So staging is a way not only of communicating to the actors what you want, but it's also triggering those emotions inside the actress. Now, as you do that, again, forget the cameras for a moment, as you do that, and you watch it, or anybody watches it. Now we're back to theater for a bit a little bit, as the audience watches that the audience by projection will respond as well. She comes into the office, she's standing in a very uncomfortable place, she's feeling uncomfortable, but the audience goes, Oh, my God, that's so uncomfortable with that. In other words, the audience is now help you are helping the audience help you connect with what's really going on. So you're actually through the staging, not only communicating with the actors, and then the characters, you're also communicating with the audience. Your staging is telling the audience exactly what's happening inside the characters. So it's a very powerful, that's why it becomes a language. It's a language between you and the actor, the character and the audience. Staging is a language.

Alex Ferrari 22:39

So what happens when an actor decides to go his or her own way in a scene where there's like an improv or they seem to want to go somewhere else? And it's not exactly what you either discussed, or, you know, it's a little bit more fluid, they want to act a little bit more fluid and not hit marks and do turns and they just want to be more in the moment. And, and there are actors, obviously, who love to be in the moment. And we'd love that. Well, how do you in this scenario? How would you deal with that?

Mark Travis 23:09

Well, it gets very tricky. I mean, you have to as an individual director, I'm talking to you, Alex, but anybody who's listening you as a director have to decide for yourself with that project, who will say you know, project by project this can change how you want to handle that how strict you want to be in terms of that kind of movement, and even in dialogue. Are you going to if they want to improvise movements, are they also improvising dialogue? how loose you want this project to be, or this scene how you wanted to, then I've done some projects where scenes are heavily, heavily improvised, but that's just that one scene in the movie. Because I felt with that scene, this is how I'm going to find something even better. So you have to decide. But getting back to what you're saying, the actor says no, no, no, don't tell me where to go. Don't tell me what to do. I'll figure it out. Two things and I'll tell you a quick story about the Actors Studio, something that happened there. The one thing we all of us human beings by instinct, will do we go through life doing tooth very simple things. We go through life seeking comfort, and avoiding conflict. So as an actor coming into a scene by instinct of that being that person this has nothing to do with actors and has to do with that he or she is a human being will seek comfort. They will go to a place on the set of the stage or in relationship to the other actors that feels good. And it will most often feel good to the actor has nothing to do with a character. So they will seek comfort and they will avoid conflict. Now we're telling stories. And as you know, as a writer and director, what are more So my stories are about discomfort and conflict. That's it. If you don't have discomfort and conflict, what do you have? You have a boring story, and you'd have. So all of us by instinct will do that. So you gotta, you gotta be aware of that my job when I'm staging, and I will tell the actors as when I'm staging a scene, I said, Listen, my job as the director is to get your character into trouble. Your job as the actor through the character is to try to figure out how to get out. That's it. In other words, I am going to create the conflict, I'm going to create the problems that the character is experiencing you through the character try to do is try to work now that gets us back, closer to what real life is like, we go through life, we have a problem, we try to work our way I want to duplicate or represent as closely as I can authentic behavior, not planned behavior, not planned emotions, not planned line readings and things like that. I want to create an environment where the actor as the character is, is working on instinct as the character. And one way to do that, literally. And I could show this is to take away from the character, the opportunity to just go wherever he wants. And people say, well, there isn't that kind of controlling? Absolutely, it is. But I'll tell you something else. It's very controlling in this business, somebody wrote a lot of words that says, This is what the character says, now there's control right there. This, this is part of part of what we're doing. We got these lines. And now if you want to get into the technical part, yeah, you got a camera here, you got lights there, you can't just go anywhere, because you go to that corner, there's no light there. You know, it's, the whole process is major control. But what I'm aiming for is that kind of major control, you got the dialogue, and you got the staging.

And But within that, which goes back to the interrogation process, total, a total emotional freedom, I'm not going to tell the actor or require the actor respond emotionally in any, any way at any time. I want it to be on instinct at that moment, under the pressures of all of this control. So that's, that's the dynamic I want to set up. But to go one step further with your question, if you want to go into this, or you have let me go back to what you said the other this actor said, No, don't tell me where to go. Don't tell me what to do. You know, give the give the actor a break, say, Okay, let me see it. Let me see what you're gonna do. Let me see, you may be surprised you make a hole, that's, that's actually a little bit better than what I had. Let's but then you got to lock it down a little bit. You can't say every take, it's gonna be all over the place, you can't do that. So you got you got to give the actor the benefit of the doubt that they may have something or you may end up which often is the case of a combination between what you were thinking and what the actor was thinking. And you find that middle ground, which is actually a richer collaboration combination of the two.

Alex Ferrari 28:14

My from my experience, I found that if you hire the right actors, they generally know the character much better than you do. They've done a lot more homework on the specific character, and given the character backstory, and all sorts of things. So they might do a little bit of business, that really adds a lot of value. And they might just do a movement or maybe just crossing the arms or crossing the legs or turning the bar and doing so adds so much to the scene that you might have not seen coming. So I would love to collaborate with the actors. But you're right, at a certain point, there has to be okay, is this what we're doing? We gotta lock that down. Okay, great. In this scene, let's talk about the scene. And maybe and we'll talk about rehearsals in a little bit. But maybe in rehearsals, a lot of this was kind of worked out as well. In in that process. But my next question is, how does staging reveal subtext? Staging has a unique ability to do that?

Mark Travis 29:10

Yes, yeah. Yes, it does. I'm gonna go back to the thing I talked about before two people talking to one turns. One turns away from these two people talk and listen, I'll have him turn towards the camera. This one turns towards the camera. So let's say these are two men talking to each other and their brothers. We know that they're brothers and they're discussing what to do about that. And this one says, I think we should put them in a home. So at this point, we should have to put them in a retirement home. And this one just turns and says nothing. I just want to ask you, Alex, what does that mean?

Alex Ferrari 29:50

Oh, it can mean a bunch of different things.

Mark Travis 29:53

Now we're gonna subtext. Now we're into subtext.

Alex Ferrari 29:55

Yeah. Just something as simple as a turn a turn. Yeah.

Mark Travis 29:59

And that's subtext, I'm not, I'm not saying what it means what I'm what I'm doing is I'm creating an opportunity for you, the viewer to start to project in what you think it means, even though the person sitting next to you might think you'd be thinking something different doesn't matter, I want to trigger the subtext to open up that subtextual zone for the audience member to fill it in, which is an important part of storytelling or filmmaking, where we are triggering the audience to participate in the telling of the story, not just watch. And I think the most engaging films that any of us have ever seen are the ones that ended for you or for me, individually, where we have been able to participate a lot. It has triggered our motion has triggered our projections as we feel like we have participated somehow in the telling of that story.

Alex Ferrari 30:54

And yet without question, without question, and one other thing about the staging process, if an actor has quirks or something that is very specific to them, should you include those in the staging? How would you include those in the staging

Mark Travis 31:10

The quirks like what I mean. No, no, let me let me ask you more specifically, are you talking to the actor himself? has these quirks are the actor is? Or is the Okay, the other part of it? My question was, what is this quirks he's developed for the character? Both? Both?

Alex Ferrari 31:27

It could be both it could be something that he literally, or she literally as in as a part of them, or they developed the lamp, the shake, whatever, you know, the handshake, whatever it is that they've developed? How do you incorporate that in the staging is incorporated a station?

Mark Travis 31:46

Yeah, my first question would be you said a limp or soft or something like that. My first question would be for that character, let's say something that's creative, not something that the actor has. How is that helping? The story? How is that helping flesh out the character? Why is how is that affecting the character? How is important that to the character we're trying to render? That's really a conversation between you and the actor. So you Okay, you've got this limp. That's interesting. Here's what I think is going to you know, it's a you do have the final decision. But even you know, you have to have that conversation with the actor, what is your thinking here, it's not in the script. Could be an interesting idea. I don't want something in there, that's going to create a black hole for the audience. They go, I don't get it. What why the limp is not going to be brought up in the script. Because, you know, it's just something that's there. And if you can make it somehow elemental to the character, you can make it make it somehow that it becomes an interesting part of the character. That then it's fascinating. It's not like the usual suspects where Kevin Spacey has that you know, straight and that he shakes it off at the end. That's that's a whole

Alex Ferrari 33:04

Yeah, but you look at Dustin Hoffman in Rain, man. I mean, his whole movement is erratic, because that's his character. So he's, he's doing his thing he's walking. Yep, he's artistic. So that will affect staging like, how? So that's why that was kind of like the question.

Mark Travis 33:22

And then with somebody I mean, the Rain Man thing is a good example. Your question whether if you have this one character who has this erratic behavior, you as the director to think, Okay, how to deal with the other characters respond to this? Are they aware of this? Does it bother them? Is it you know, now in rain man who was a big thing between Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman, those two characters, as brothers, you know, because he's dealing with this autistic brother, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. So it can't be just a quirk for the sake of isn't that an interesting quirk, because that won't be an interesting quirk if it becomes a significant part of it. Now, the other part of what you're asking is if the actor himself has this quirk and a lot of actors have quirks which we've seen over and over and over again. And the if it's a quirk that we're very accustomed to me for some reason, I'm thinking of Owen Wilson and facial expressions and, you know, things like that we've seen a million times he's a great person to imitate, I guess, you know, say, do I want that? Do I want that or with a skilled actor? Do I want to eliminate that? Do I want to have him shift into a character who does not have the quirks he has?

Alex Ferrari 34:45

Like I was thinking of someone like Daniel Day Lewis in There will be blood movements are so kind of through the wall kind of movements. He's very powerful. He's very imposing with his movements. You know, and when he walks in a room, she just walks very differently than he did in Lincoln. Let's say. It's extremely difficult, right? So as a director, you're looking at them like, okay, so he's bringing this energy. And if it's Daniel Day, obviously, this is a different conversation. You go, Mr. Lewis, how, how are you going to walk into scene? Let's figure this out how we work. But if but if you have an actor that is bringing that kind of energy to the scene, which is is part of the character, that was the kind of question like, how do we work it and there might be that erratic pneus around it and the Rain Man and Tom Cruise situation is they're both very opposite ones very erratic. And Tom Cruise generally is stoic, you know, controlled everything. The only thing that's knocks him off kilter is Raman Raman is the one who does not come off kilter and things like right, so it was just it was just an interesting, just curious to see how we approach it. I think we answered the question.

Mark Travis 35:59

Yeah, but let me go back to it. There will be blood in Daniel Day Lewis. And you're right. I mean, Daniel Day Lewis has a whole conversation by this by itself, but an actor who is taking on a behavior or physical behavior like that, because they feel like, first of all, that probably empowers them to get into the, you know, you don't want to just take it away. And I think for There will be blood that it was very appropriate for this character who basically was bulldozing his way through life and through everybody else, and didn't care. So it sort of represented that. But think about this as the director, you have to think about this character. Again, the same character, there will be blood. Is that the way he always moves? Or do we see a moment when it drops away? A private moment? Can we see? In other words, what can you do in relationship to this moment moment, see a moment where he is vulnerable, and he is alone. And he is private, that we can see what I call the window of true nature, that window of true nature of a character's Who is he really is this a facade that he has developed? Maybe over the years, in the end, he will always behave that way. But it'd be beautiful for a moment to see that when it falls away, when it doesn't serve him.

Alex Ferrari 37:19

The man the armor is off, the mask is off, and it's off.

Mark Travis 37:24

And then it becomes even more chilling, because we've seen something privately that Paul Daniel and all the other characters in that movie have never seen and we, the audience get to see that.

Alex Ferrari 37:36

Yeah, I mean, you look at some a character like Hannibal Lecter, and Sansa lambs. I mean, Jesus, we're talking about two different energies. I know he's, he shows the facade. But then his true nature comes out when he's literally eating a guard. Later on, but we see him as this beautifully, poised, elegant, speak, listen to your music. But the moment he has an opportunity, the true nature comes up. And that's what drives that's really the one of the most chilling parts about that, about that character is that he puts on one face, and we fall in love with a cannibal until you see him eat, act erratically as a violent person.

Mark Travis 38:24

It's interesting that in the course that I'm doing now the staging course last week, speaking of Anthony Hopkins, last week, we were looking at the father, I don't know if you've seen the Father.

I've heard of it. I haven't seen it. I highly recommend it

It's a man who's dealing with dementia. Yes, I'll give you a and his daughter is trying to bring in a caretaker to take care of him. So basically, so she can leave town. That's simple. And she has brought in a potential caretaker and he knows exactly what she's doing and doesn't want it. And he meets the caretaker. And he's excellent. And he's charming. And he's delightful, you know, and basically showing I don't need any help. He goes off for a moment to get his watch. Now he's alone. He's coming back. And there's one moment Alex, where he's coming back to talk to the caretaker and his daughter again, and he stops in the hallway. And he just stops. And all he does is stop. And you see oh my god. That's a moment. So what I call an empty moment, a moment that you could put project anything you want into it was Is it fear? Is it Indecision is no what is going on? And then a moment later, bam, he's back in the room and He's entertaining. Now that little moment is a moment of true nature. What's really going on with that character? And it's all done through staging. It's not in the dialogue. It's not, it's not probably in the script. I have the script. It doesn't say that he does that in the script. It says he can comes back with the watch. But there's that moment which he may, quite honestly, clearly at the Hopkins may have just done on his own comes back and he stops just thinking, thinking, and maybe he's thinking about how am I going to handle this problem? Maybe he's thinking I'm in trouble. Maybe Maybe he's got where he was a second maybe? Yes, exactly. All that all those maybes which we go, are I go? What's going on? Are you okay? Are you okay? Then he comes back in and he seems fine, but there's the cover the mask we were talking about, and there's the cover. So all done through staging, staging, is that powerful?

Alex Ferrari 40:43

Now, what is micro staging you said that earlier Can you talk a little bit about micro staging

Mark Travis 40:48

Yeah, well, you're doing it right now that was that was That was lovely.

Alex Ferrari 40:58

That was that was that Doc thing acting sir. That was acting. Anyone, you should watch the video guys to see my performance I just put on there with micro staging.

Mark Travis 41:08

Okay, this mic, these are my terms, micro staging and macro staging macro staging for a moment is walk over to the to the desk, sit down those those pretty much those big moves, you know, and even in an action adventure action thing, you know, this I mean, a fight sequences, all macro macro, macro. Micro staging can be this simple. Two people sitting at a table. This is why say you're doing it now. And one person is talking to the say it's a at a restaurant, a cafe, as a man and woman, woman is talking to the man about something doesn't matter what it is right now. And the man is I'll give you two scenarios to staging. So both of them micro, the man is just sitting there listening and nodding. Or the man is looking down at his fork and moving it. Now those two are totally different. Totally to add some micro, the tiniest little movement, or two, take it one step further. The man is listening to her right. And she's talking about people, we don't know who they are. And she she mentioned George. And on George, he looks down at the fork and picks it up. What does that say? That's microstate G. He has actually changed his behavior, that little shift there. Again, it opens it opens up that space that we go something about George, what is it about Jeff? She mentioned George, he shifted. If I just said to him as as an actor. You know, when she says George, just look down to the fork and pick it up and go, Okay. Easy to do. Very easy to do. Anybody can do it. You don't have to be a trained actor to do that. But that we see a shift in the character. And they can easily be something just in terms of eye movement. And a lot of very skilled actors. You watch them if you watch Anthony Hopkins, or you watch Meryl Streep or Daniel Day Lewis, or some of these people, Olivia Coleman, you watch them you can you watch for those little things that they're doing sometimes, maybe by plan, often, just by instinct, because there's so into the character, these tiny little, you want to make sure you capture that. And those are micro stages. Those are the micro staging. More than the macro stages are the ones that allow us in deep inside the character.

Alex Ferrari 43:36

That's it also reveals subtext when you do that. Absolutely, absolutely. So like the example of George with the fork. It's something simple, so simple, so small, but it says volumes. So if you're talking to me and I start yawning, that could either mean I'm just tired, or I'm bored, or I don't want to be here. And then you can insert what you want there. And it's just in the eye movements and things like that a look is worth 1000 words, and just God

Mark Travis 44:12

Give me another example, husband and wife in the kitchen. This isn't a real Sam just making it up husband and wife in the kitchen. He's sitting at the kitchen table, maybe some papers and stuff. Whatever he's doing there. That's his independent activity he's got and they're talking, he's talking about his work. And she's at the sink with her back to him washing dishes, very simple. And he's talking about work and she's washing the dishes and washing the dishes. And he mentions his boss and a client. And then he mentioned his secretary Cheryl, on the word Cheryl, she stops washing and he keeps talking. And maybe a moment later she starts washing again or she puts the plate down That's micro staging. That's some text. And he's not looking at her, she's not looking at him. But it's a little piece of behavior we expect. When someone's doing an activity like washing the dishes, they'll just keep washing the dishes until they're done. Those independent activities is such a powerful territory for staging, that you can make a slight adjustment in it. That is powerful. This one that I just explained, I was in teaching in Munich, I remember this and some actors were sitting at a table, were asking me about exactly what you're asking me about. So I had the two actors, doing some I gave one of them an independent activity, whatever she was doing, and the other one had to improvise a monologue. But she had to get the name like, I'll use Georgia George in it. And I asked the first one, I said, when do you hear the word, George? Now, these are two actors hear the word George's, you're going to stop that activity. Right? And hold and freeze until I release you. And I say, and I say action again. So they did. So this is totally improvised. So these two actors when I said the one said, George, and the other one stopped, I could see her the one who stopped started shaking, just shaking. And then I said, action. And she went back to and then two seconds later, she jumped out to see what Oh, my God, I said, what happened? She was I don't know. She says that was so powerful. In other words, that staging to her, she knew what she was going to do. But she had no idea how it was going to impact her. And the other one had a similar thing that she said, Georgia, she saw this react, so they emote, they the two actors responded emotionally to it. And that's how powerful it is.

Alex Ferrari 46:48

And if you can capture it on camera, then, yeah, you got money.

Mark Travis 46:52

Yeah, and the great thing, like what we're talking about independent activities, and some of those Microsoft, they can do it again and again and again and again, take up to take up to take exactly the same thing. And being skilled actors, they will allow the impact to happen every time just allow it. It could easily not have it happened. But you don't want to stop it from that you want it to happen. You want that, because that's part of what you're doing. That's part of the character and part of the moment. So it'll always work.

Alex Ferrari 47:22

So now let's say you're in rehearsals, and your staging and rehearsals, the actors are working worked out these micro stages worked at the macro stages. And we you know, we kind of had an idea of what the scenes going to be like, then we go on the day to location, and the location dropped out, we got this other new location that's completely different than what you've done. You've got five minutes, 10 minutes to restage this, what do you do?

Mark Travis 47:49

First of all, I'm in the initial rehearsal use stage at for one location. And but what you actually hopefully if it was staged, well, you did explore and you found the essence of the scene, and how the staging was helping you get to the essence of that scenes, and what's really going on between those characters. Now, the staging is helping you do that. That's what you have to rely on as the essence of what you achieved. Now, you now you look at the new location, and you say, okay, actors, we have to change the staging, but we're staying with what we achieved. Aha, the relationship between the two of you that sense of betrayal or the surprise of this moment, but we're gonna have to restage it very quickly, still going for what we had, but in a new location. So it's not do the same staging. Its render the the essence of the scene in a slightly different way, but still getting what the scene is really about what the, the arc of the scene is, what the transformation in the scene is, what the shift in the relationship is the cuecore moment of the scene, you're still getting all that you just have to do it a different way. And that's why I recommend to directors when you sit me down even before rehearsal, figure out how you want to stage the scene, the three different ways, three different ways in the same location, you have this location, it's the kitchen or whatever, three different ways. Doing it three, two, and a three dramatically different ways. I mean, and for instance, you can stage it in a way that okay, this is going to take a long time to shoot because there's a lot of movement, but boy, I like it good. Staging, again, when there's no movement, very little movement, where you're relying on micro staging more than macro staging. So if you get there and you only got two hours to shoot the scene, okay, I'm going to shift, I have to shift to something that's simpler. Or, as you've mentioned before, the actor comes up with an idea if you have three different ways of doing it. They're going to come within one of those, you have all these options you can go to and if you've done it in three different ways, they all seem like they kind of work for you You have been hitting on the essence of the scene, what's really going on the scene. The staging is not the scene, the staging reveals the scene. So, so if you've done three with different ways it can be revealed. And you may get on the set and do the one you like the most and go, Gee, I don't know, Wait, man, I got another idea, you may just shift because you're going I know, this is not working, as well as I thought it was going to. Hopefully, because of my background in theatre, I'm really advocating this, hopefully, you've had rehearsal time with the actors. And I don't mean rehearsal on the set, because that's really not rehearsal time. That's just that's you eating up production time, is very expensive rehearsal time, you're very, you should not be rehearsing on the set, you should be reviewing what you did or clarifying what you're going to do. And that's it not exploring, oh, how am I gonna stage this scene? I need to do do that earlier.

Alex Ferrari 50:57

No. And the thing that I love about this technique is that you you basically are able to adjust on the fly to whatever scenario comes from because you have multiple angles multiple ways to cover the motorways to stage the scene, right, but they all reveal the essence of the scene in different ways. And if you can get the essence, then you could put it in a box, or you could put it in a very complicated location is still going to reveal the same thing. There might be the chess pieces will be moved a little bit. But the essence

Mark Travis 51:32

Exactly, yes, that that's you. That's what you have to capture the essence of the scene.

Alex Ferrari 51:38

Now you've talked about in the past inner dialogue? Can you talk a bit about inner dialogue? And how does that work? Or help non verbal scenes and scenes? That is literally just two people looking at each other or very Hitchcockian in that way. So what is inner dialogue? And how can that be used?

Mark Travis 51:56

Well, inner inner dialogue is first of all, it is very important, because it is exactly what it sounds like. It's inner. And it is a dialogue. It's not, we don't usually just have thoughts, we usually have a dialogue. You know, I think I'll do it. No, that's not a good idea. That's a dialogue, you got two voices going on. Or you're looking at another character and another person you go, I wonder what he's what he's what he's gonna do. No, I don't think he's gonna do that. That's actually you're having a dialogue with yourself. So it is a dialogue. It's not just thoughts. These inner dialogues are crucial, because, number one, we as human beings have them all the time, we're doing it every every day, even, you know, moments before I met with you for this podcast, I'm going through my MO, I'm here alone at the moment. And I'm, I'm having a dialogue. It's preparation is I mean, it's what we do this all the time. So if we do this all the time, we have to assume I have to assume characters, all our characters are doing this. The thing is, it's not written in the script, what they're thinking, if you want if the writer wanted to write that they'd write a novel, this is not a novel, this is a screenplay, all we have is the spoken dialogue. The other aspect of this, which we talked about, I think last time in 2017, is, in our minds, all of us, we have what I call the committee, which is all the voices, the voices that talk to us, we talk to them, we work things out, they tell us what to do. Some of these voices represent people we know mom and dad and neighbors or whatever. So this is committee going on. And in our mind of discussing things. That committee is really crucial. And now we're getting back to the interrogation process, which we won't go into. But think about it that every character has a committee, every character is rich in thoughts process going on all the time. So if you have that scene that you're talking about, where it's just two people sitting there, let's say it's in a bus station, and the two people are sitting there across from each other, and they're both strangers, I will say, but they're going to meet eventually, but they're just staring at each other. And that's that's the scene, they're just looking at each other. Well, there's got to be a world going on. Inside each other. There's going to be a major dialogue, major conversation inside each of them. And two things. What I do with working with actors, is many times and in fact, I did a film where you can see this how this works. Many times I will have them before the scene just before before we're shooting, verbalize what's going on out loud. Two of them at the same time. They're not really talking to each other, but the two of them just verbalize verbalize, verbalize verbally. They're saying what they're saying. And then they're just waiting to hear Action. Action and what happens on action is the verbalizing stops. But the thoughts keep going. In other words, I actually activate improvise and activate the inner dialogue. So it isn't like, oh, what should I be thinking about? I'm having them say it. And it's very powerful, they are saying it to the other person, because the other person is in the room. But they're not saying it. That's not a dialogue between the other person. So they're exposing it. And the powerful thing about this way of working is those two guys sitting across from each other in the bus stop. They hear what the other person is thinking, now they have a cent now there. And people say, Oh, they shouldn't be hearing what they're thinking is Oh, yeah, they should, because what they're hearing is what they're thinking that the other person is thinking. I mean, I've got to connect these two people somehow. So that inner dialogue is a very, very powerful, very, very powerful tool.

Alex Ferrari 55:45

And it's really interesting, too, sometimes you can give two actors two different motivations, without telling each other what that motivation is, which can be opposed to each other's, you know, going out the scene. And that makes the best scenes ever, because one actor is like, you know, I use the direction once he's like, I need you to when you're yelling at this person, pretend you're trying to communicate to somebody in the other room. And it's in that kind of gives you a level of where I want the volume to be without you going nuts, things like that these little little techniques that you can use along the way. Really help now, how can you create tension with staging?

Mark Travis 56:27

That almost does it all the time. One thing to think about. It's a good question. Staging, this is something I discovered years ago, it suddenly occurred to me, when I was teaching, I would talk about obstacles, character obstacles, and I would say, okay, there are obstacles that come in three categories, other people are obstacles, okay. The environment can be an obstacle, you know, either the physical environment or the social environment, attitudes of whatever, so the society. And the third area is obstacles within yourself, you know, internal obstacles. So those are the categories of obstacles. And as I was teaching, I realized those three categories are the same categories as staging your staging people in relationship to each other, staging people in relationship to the environment and in relationship to themselves, whether it's the body language, or how they want to be seen, or how they are seeing. So. So that's, there's a very strong link between staging and obstacles. And I realized that what I'm doing with staging is I am creating obstacles constantly, constantly, if an actor sits down, so I'm gonna sit in this chair, and I say, okay, sit there, do me a favor, slide forward on the chair, they'll slide but not a little bit further, a little bit. He says, I'm right near the edge, I said, good. I just created an obstacle. He says, This feels uncomfortable, I say, good. And he realizes I have created now this is just an body language. You know, he's, first of all, it looks great, because it looks like he is uncomfortable. I don't know why the character is sitting that way. But he is not comfortable within himself. And this has created an obstacle within the character. And it will actually trigger something in the other character when he sees him sitting there, because the other actor as as the character will also read that behavior, right. And now we're creating now I'm creating tension, I'm creating tension within the body, I can create tension between two listed this has to do with the turning faces or something like that, between two characters, what happens if I have this character move away from him? Now I'm going to create while he's in the middle of that speech, that you know, this one is playing this big speech, and this one starts to move I go, that's that's going to create tension. Or in the environment. Let's say we're in the office of the boss or something like that. And the young woman applying for the job walks behind the boss's desk. While there's a problem. You know, it's not where she's supposed to. We know that when we see the room, we know what the territory is, we know it's his space. And maybe he's gone off to the side of buying a piece of paper or something. And she walked behind. Now I've created tension and not only creating tension between the characters, and creating tension with the audience, the audience, oh, that's dangerous, what's going to happen and I want that the audience to feel that and it has nothing to do with the dialogue. Hopefully, it's all supporting the dialogue supporting the essence of the scene, but through the staging, I'm creating emotional responses in the actors, the characters and the audience. By creating tension and then relieving it when I want to. So you go Ah, okay, now what now we're fine.

Alex Ferrari 59:51

Which by the way, is an art because there are movies that soaps, some some of these more testosterone ridden movie is sometimes don't let go of the tension. They just hold you and hold you. Where becomes very unpleasant for the, for the, for the audience I've had that experience handful of times in watching a movie that the director just wanted to keep it cranking and cranky. Like, no, you got to release the valve. You've got to release the valve a little a little bit. Even it's released the valve.

Mark Travis 1:00:24

Oh, yeah, absolutely. He was a matt he was he was a master of it.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:29

Which speaking of Hitchcock, how do you then create fear with staging you know, intimidation, power, that kind of thing. Kind of like I'm the first scene that comes into my head is the Godfather, where he's in that room, stroking a cat with amazing, which, after watching the offer, which I tell everybody, they should watch the offer, that maybe the TV series about the making up the Godfather, cat. That wasn't masterful direction. He was just a cat that happened to be a series.

Mark Travis 1:01:03

There was a stray cat on the set. That's what I heard that Coppola picked it up and gave it to Brando.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:11

In the show. Brandon's picked it up.

Mark Travis 1:01:13

So he doesn't Yeah, it doesn't matter. But it was like this. And it was a great cat. It was a great cat,

Alex Ferrari 1:01:20

Just chilled and relaxed. He wasn't like, Well, yeah. Because you know, you don't want to include animals into a scenario where you don't have to. But that scene is indicative of power. And there's also lighting and presence. But how can you analyze that scene a little bit in the blocking of it as an example? Or pick another scene if you'd like?

Mark Travis 1:01:39

Yeah, no, no, that's a good scene. But your question was on fear,

Alex Ferrari 1:01:43

Will fear power and intimidation? I mean, he has all of those in that scene.

Mark Travis 1:01:47

Right? Right. And how do you create it?

Alex Ferrari 1:01:52

With stagging

Mark Travis 1:01:54

Well, one thing is, which is part of a staging that is created there is in the silences. You have you have the man across it, you know, my daughter, she was she was raped, I think and I need you know, I need justice. I need justice. And then there's a long silence. And we go Oh, shit. You know, in other words, by with silences, and then the cat helped with that too, because it's a gentleness against something. And, and also in the editing of that scene. It's a long time before we see Brando. We see his hand, we see him from the back. So long, you know, we withhold that for a long time. But this this, the silence is really moment. The even in that scene, he says, you know, you come to me for this help. But when's the last time you showed me respect? Now that's just great writing. Oh, you know, I say this, this is not going to go well. And I think there's something beautiful about that scene. Because at the end of the scene, he says he does say, I will help you, and you owe me because someday I will come someday I will come to you. Maybe never but someday I might. Actually he does in the story. But he's he. But the fear is going to work in the scene as much as you can away from that ending go in the opposite direction. So even in the staging, when Brando finally gets up, and he walks around his desk towards the guy. Now what's going to happen? There's also in the staging of that scene, but because I think Robert Duvall and James Caan are in that scene. And there's early on in the scene, that scene, I think, is a shot. It's a great shot or a divan. Devall is in the foreground, I think it's divots in the foreground, and we can see Brando, the godfather in the background. I think it might be at the moment. I may be wrong about this, but it might be the moment that I think it is that Brando is getting up. Right. He releases the cat and he starts to get up. Well, James Caan and Robert Duvall respond immediately they start to rise, and you go, Whoa, there's power. You know, they rise because they don't know what he's gonna do. But it's like, the boss is Wolverine ready? I I'm ready, and and where they're moving around, they're not going anyplace specific, but they're sort of positioning themselves to be ready. So it creates a tension in the whole room, which the guy asking for the favor. It's got to feel like everybody's moving. Is this good? Or is this bad? And that's what you want to create that fear and create that tension.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:53

And that staging is so powerful because you're absolutely right. Nobody knows who the Godfather is. This is the Now we all do because it's a legendary film. But when that in 72, when people were watching it, nobody knew really what this meant. So just that that staging of he stands, the other two stands, it says volumes about the power that this man wields. In addition to everything else that's going on the scene with the, with the cat, and the lighting and the performance in the dialogue. It all works. But that staging just adds this this gravitas to this man, even more so than he already had nothing mentioned. It's Brando, they already brought us

Mark Travis 1:05:35

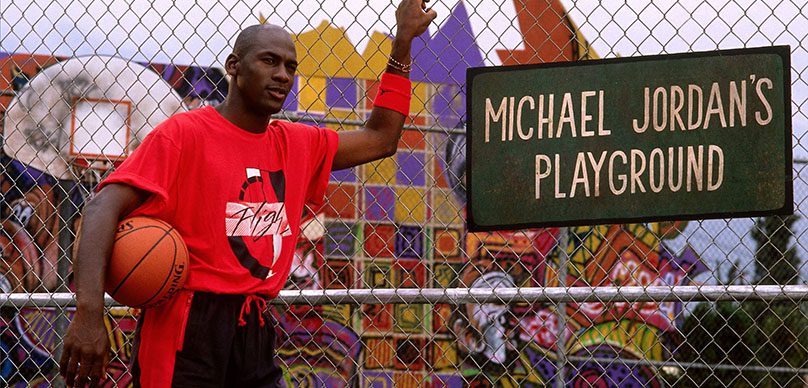

Yeah. And also Alex, you're bringing up a great point. And I'm going to refer to Butch Cassidy, who's in a similar way, that that scene with brand, you know, we got the Godfather, we got Brando playing the guy I'm going back to before it's released. And there were a lot of people didn't want Brando, but forget about that. But you you are the director telling the story. And you're going to introduce this main character. And your what do you want? What do you need to establish besides the story, your main thing is you need to establish this guy that we know by the end of the scene, we know who he is. This is your introduction to the audience of who this guy is. And it's actually beautifully done, because it's, in a way in terms of the whole story. It's a relatively insignificant scene. But it's very significant in terms of the introduction, so you've got to pull that off. The reason I said which Cassidy, William Goldman, when they were about to the writer, not the director, William Goldman, when they were tested it and they had Paul Newman, who is that time as a major star. And they were talking about Robert Redford, which is basically unknown news.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:51

Basically, it was coming up. He was, it was coming up,

Mark Travis 1:06:53

But but he wasn't at the level of Newman, neither one. And a lot of people said, No, you gotta get someone who's at the level of Newman. So William Goldman knew he had to write a scene, which he did, where he can establish Sundance Kid, or Robert Redford at the same level, and Rob respect as Newman and one scene at the beginning of the film. So from then on, they are equal. And that's the scene where Sundance Kid is playing cards, and he has accused someone else of cheating, or someone accused him of cheese. And Newman comes in and says, Come on, we gotta go. We gotta go. He says, No, he has to apologize. First. What he has to apologize why he accused me of cheating. He has to apologize. Come on, we gotta go. We gotta go. And then in that scene, the way it's written, Newman says, Butch Cassidy says, Sundance Come on, and suddenly the room changes. People. Sundance, your Sundance. Because yeah, he's got to apologize. No, I'm not going to apologize. I caught up on Sundays, and someone says, Whom? Are you really that good with? Which means with a gun? Are you really that good? In other words, the now we're hearing about the legends about this. And this is a famous scene, and maybe by this time, Sundance is standing up. And they I don't know, someone says, Can you shoot that would have that bottle over there. Right. And he's just standing it says, just stay there. And he shoots and he misses. Right? And they go, okay, he's not that good. Then Sundance says a key lysis. Can I move? Make a what? Can I move? Oh, yeah. So we start to move it. He's actually starts moving a lot and shooting, and that bottle goes first. And then he says, I'm better when I'm moving. Did you go hold? That whole scene was so the wit. So we go, Who the hell is this guy's amazing. Bring him up to the level of Paul Newman. So when they walk out of that scene, they're at the same level. So it's the same thing is with the godfather. How can we create a scene and create a moment to bring that recognition of a character to a certain level before we launch into the full movie,

Alex Ferrari 1:09:15

And as you were saying that the character that came into my head was Val Kilmer is Doc Holliday and tombstone similar in a similar way, if you don't know who Doc Holliday is everyone's when you hear the rumblings from others. How fast Yes, and he's a he's a lung nerd. And he's got a fairly something called they call them a lung and I'm not sure if that's appropriate or not, but he has that was that they called him in the movie and, and how he drinks all day and even with all that stuff, he still better than anybody else in there. Yeah, that's pretty remarkable. And the other character, which I haven't seen in recent years, anyone do this. John Wick, my God. I mean, The way they set that character up is so beautiful because for the first part of the movie, you don't know what John Wick is capable of doing right at all at all. And then only by the other characters, looks, micro stagings, all these kinds of things. Like when when he opens up the door this is after he already showed a little bit of what he could do. When the cop opens the door. He's like, we heard a couple shots. You're working again, John. It's just so brilliant. But then like the biggest, baddest, you know, criminals. Just hearing his voice is like, hearing the Boogeyman. You know, like it's over, you're done. Now, the boogeyman is coming to get you. Death is coming. It's so fascinating. And it's such a brilliant look at they're holding it off to like, Episode 1/4. The fourth one's coming out. And I think they can sign for four and five. If they're brilliant films. But that's that's a really beautiful case of how the outside characters and environments really set up the the main character.

Mark Travis 1:11:05

Yeah, this another similar situation, which I love to share with you, which has to do with as good as it gets. Oh, Jack Nichols. Yes, Jack Nicholson. And that horrible character, he has to play the horrible human being which almost everybody in the film calls him a horrible human being. But I have two friends of mine. We're working on John Bailey, the cinematographer. And Richard marks the editor. And what I heard is that they had finished the film and they had the first cut or whatever, and they did previews. And everybody hated the film for two main reasons. One, one reason they didn't understand what was wrong with this guy why he was they didn't understand his illness

Alex Ferrari 1:11:46

Didn't show like, they didn't explain it.

Mark Travis 1:11:50

I'll tell you what they did. Okay, they didn't understand his illness. Let's put it that way. Is OCD at all. And the whole idea of any him falling in love or anybody falling in love with him? Forget it, forget it. So the whole it was a disaster. So they went out and shot two more scenes. The one scene in terms of what you're talking about the OCD, the scene of him washing his hands with the Neutrogena soap and throwing the soap things away. And remember, he walks down the hall goes in there and that was not originally they had to show him the OCD, right a big Guinea so you go, okay, he's got a problem. He's got a problem. So they've shot that scene. And the reason it's shot the way it was shot, which John the cinematographer, explained to me says we only had that wall. That's the only wall we know because you're going back to do a reshoot. You don't want to put the whole apartment back together again. The other thing that they shot in terms of him falling in love, which was not in the original was him walking the dog and the dog jumping over the cracks. Okay, the dog jumping over the cracks, which actually became the poster the scene, and then him lifting up the dogs. He still has the little plastic gloves and holding the dog and going oh, yeah, now, but a key thing about that scene was a shot to two women who are out in the park wherever he is seeing him and going, Oh, isn't that sweet? That tells the audience what to think about Jack Nicholson he is capable of being soft and loving and caring. It's told through and told through to other characters that we don't even know who they are.

Alex Ferrari 1:13:39

It will steal the old trope if you want to show a villain have them kick the dog, if you want them to be if you want them to be loved to have them be next to an animal or man next to a dog. It's as simple as that it says everything you need to know about the character. And what I think I loved about that is that he did not like the dog. And it took a minute for him to figure out that he really did love him to the point where he when the dog had to go. He was like, I could come by and see him right. Like, completely dreadful. Gotcha. Brilliant, brilliant, brilliant. Oh my god.

Mark Travis 1:14:13

I love the moment when he's trying to get Greg. He trying to get the dog and Greg Kinnear to reconnect the dog and he's pointed the dog don't talk to him. Go look at him and don't come to me.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:28

That's the big, he likes to bake. You'd like some bacon. It's not me. Right? It's such a tour de force. I mean, James L. Brooks is an absolute master. I mean, but look at that. And for people listening someone like James L Brooks didn't see that. He shot the whole movie. It happens all the time. And then they didn't like it. So like you had to add a couple things to make him likable.

Mark Travis 1:14:55

And I think you know it's it's a great post production story and there are many like that. So as you know, many like, but the first thing is recognizing, okay, it's not working, what's missing? What's missing? What's missing? And how can we get it in? How can how can we what can we what can we do to take care of the element that's missing or the clarify the element? That's confusing? Because that's part that's part of your job. As a director, you're going to have to do that. This is why Woody Allen now I don't know if he still does this. But years ago, because I had several friends of mine who were in Woody Allen films. First of all, he doesn't rehearse. And he doesn't think he's a good director of actors at all. He says, I don't I don't know how to work with actors, but I do know how to cast but that he his budget, I think 25% of his budget was saved. For reshoots. He would shoot the whole movie, go into post production, put it together. And then he's got this chunk of money for reshoots. Now, that was his process. That's an expensive process. But that's what worked at once he could see the movie and see how was working, which is actually a luxury to go back. So I'm gonna have to reshoot some stuff to make it work. That's a way to do it.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:12

And I mean, he the reason why people always asked you know about Woody and you know, his, I mean, he did a movie a year for 40 years. 30 years. I'm like, No, it's it's it's on her record, but he keeps his budget so low, that he has complete freedom, and then cast the biggest movie stars in the world who come to work for him for scale. It's good work if you could get it, sir.

Mark Travis 1:16:38

Should we all be so lucky?

Alex Ferrari 1:16:42

He's Kubrick, bow Kubrick Kelly did movie every five, seven years, he didn't want every single. Now, Mark, I'm gonna ask you a few questions. Ask all my guests. What advice would you give a filmmaker trying to break into the business today?

Mark Travis 1:16:59

Well, there were two things. One is because your question is trying to break into the business. That's a fact I would say talk to Alex, my friend.

Alex Ferrari 1:17:10

Because a few podcasts that cover that topic.

Mark Travis 1:17:13

As a few I'm sure there are. I mean, the whole thing of breaking into the business, getting into this world of filmmaking, getting into the system, the industry, the machine, whether it's at a studio level, or low budget, no budget level. It all has its challenges financially, artistically and all that it's huge. And I would say you know, keep your expectations low. Make a film that you know, you can make. In other words, don't, don't, don't push yourself. Make that film make that short film about two people in a restaurant or whatever it is. And it's a short make something that you know, you can control that can show what you're capable of doing what you are capable, that you are capable of working with these actors. You're capable of getting these performances if you wrote it that you are you are you you know how to write a screenplay. When I say keep your expectations low, which means keep your budget low, so that you're not pushing yourself to try to achieve something that is not within your budget. It's not within your timeframe. It's not within your skill set. It's in your imagination. I got that keep it simple. Keep it some some of the best films I've seen. Are I've seen some great I'm sure you I know you have a five or eight minutes long. And there are a downing power fifth. There's a short film I don't know if you've seen it. Alex called the nail nursing a couple sitting in the living room in the whole scene. They don't move they just sit he she's on the couch. She's on the chair near the couch. And she's we hear her talking about you know, she's she's suffering from these pains, like headache payments and all of that. And we see her from the back we see him he's not in on and suddenly she turns her head and we see a nail protruding out of her forehead. Okay, a nail. No blood just now. And he goes I think it must have something to do with the neck. No, no, it's not the nail. It's not the myth that's and I go and there's a hole in it but it gets into what this story is really dealing with is men and women and how they deal with problems that she keeps denying what he thinks he sees and he keeps trying to help it's really about male female relationships. But it's all about the nail

Alex Ferrari 1:19:41

It's not the nail but the nails in your head. It's not the nail it's not it's not the nail

Mark Travis 1:19:45