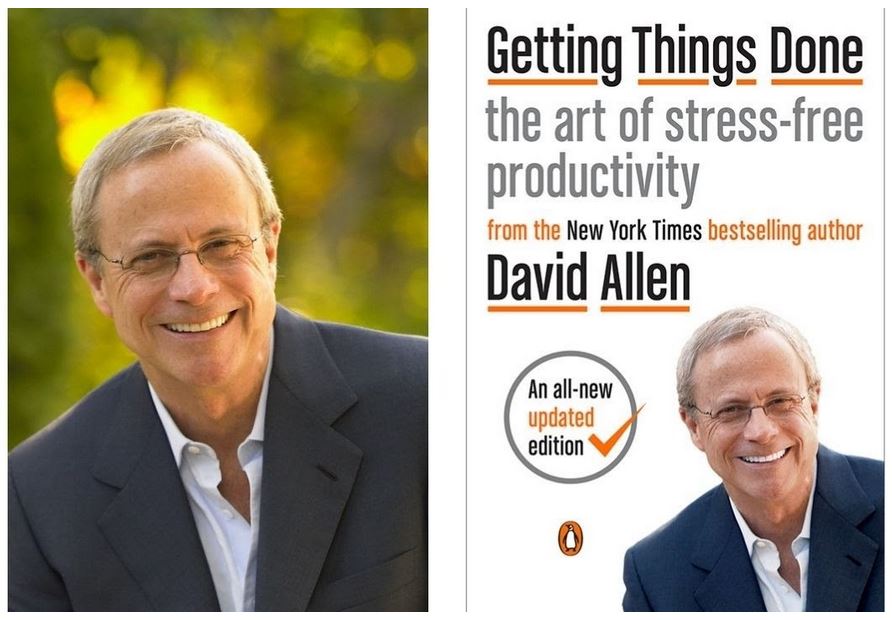

David Allen is a productivity consultant and the author of the book “Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity.” He is widely recognized for his expertise in personal and organizational productivity and has developed the GTD (Getting Things Done) methodology.

In his book, “Getting Things Done,” Allen presents a system for managing and organizing tasks and projects to increase productivity and reduce stress. The GTD methodology focuses on capturing all tasks and commitments into an external system, clarifying their meaning and desired outcomes, organizing them effectively, reviewing and updating regularly, and taking appropriate actions. The book has gained significant popularity and has become a widely implemented system for personal and professional productivity.

David Allen has been involved in coaching, training, and consulting with various individuals and organizations, including Fortune 500 companies and government agencies. He continues to speak and conduct workshops on productivity and personal development, sharing his insights and strategies to help individuals and teams enhance their effectiveness and achieve their goals.

Alex Ferrari 1:54

Enjoy today's episode with guest host, Jason Buff.

Jason Buff 1:59

Without any further ado, let me get to David Allen, a quick introduction. He is the author of The Amazing book, Getting Things Done. It's a book that's influenced tons and tons of filmmakers out there, in addition to people, you know, he's spoken at Google, he's done TED talks, I'm really lucky to that he's come on the show, because he he influenced me a lot too. You know, as a creative person, I'm kind of all over the map and fairly disorganized. And his book really kind of lays out a plan so that you can, you know, basically get things done how that you can, you know, start working on things, not having a million things in your head. You know, especially for screenwriters, or people who are trying to produce a movie, it's hard to know, sometimes you know what to do next, you wake up and it's like, it's such a large enterprise writing a screenplay or producing a movie or whatever you want to do. It's so huge. It's like, what am I going to do today? What am i What's the one thing that I'm going to do today to start moving forward. And you know, his book, lays that out and talks about a lot of different things. And we'll get into that. So anyway, here's my interview with David Allen, for the people who, you know, are listening to this are mostly writers, producers, people that want to make independent films. And I was hoping that you could take a moment just to talk about the GTD system, the Getting Things Done system, and what the idea is behind it, the concepts behind it.

David Allen 3:24

Sure. One of the basic concepts, is that your heads for having ideas, but not for holding them. People actually don't need time they need space. I mean, how much time does it take to have a creative idea? Zero, but you need room. So what the GTD system is, is really was over the years, this sort of unfolded, as to what are the techniques that actually your that allow you to actually clear your head, get stuff off your mind without necessarily having to finish them? And still, you know, be committed to them? So how do you manage all those agreements with yourself in some external way, as opposed to having your head as an office, your heads a crappy office, by the way, it's a crappy studio really is I mean, it'll if you have stuff in your head, there's a part of you that thinks you should be doing all of it all the time. So your head is is consistently trying to multitask what you can't do. That is you can't focus, you know, with focused attention on more than one thing at a time. But there's a part of your head that's trying to do that if your heads the only place it's holding stuff. So just like people keep calendars, you know, I say, Well, why do you keep a calendar? Well, because my head can't do that. Well, why do you think your head can do everything else? And not that? It's like, well, doesn't make much sense. If you don't want to track stuff out of your head, throw away your calendar, don't be intellectually dishonest. So it's really about how do I externalize and objectify all of my work and work in the broadest sense call anything you want to get done? That ain't done yet. That's get cat food as well as you know, submit a new business plan as well as produce the next movie. So all of those things just need to be externalized. That that allows you to see the difference. And actually, you know, cognitively catch the difference but and of weight between dog food or cat food and produce movie in your head, believe it or not, they take up about the same amount of space. And either one will wake you up at three o'clock in the morning, when you actually can't do anything about it, your head is actually kind of a dumb terminal. And it really, it you'll be driven by latest and loudest by things in there. Right? So that's really all that's behind it. So but there are specific techniques, you can't just you can't just clear your head by meditating or drinking. You know? I know so you can leave your head or numb it out, but it won't clear it.

Jason Buff 5:56

Right! So can you talk about some of the techniques that you recommend?

David Allen 6:02

Sure, I'll give you the 22nd version. Okay, whoever is listening to this, hang on, ready, capture any potentially meaningful thing on your mind in some trusted place, that you then clarify exactly what that thing means sooner than later in terms of whether it's actionable, and if so what you're going to do about it, the next action and the outcome you're committed to, then step back and review those things in appropriate categories. So that some part of you is constantly maintaining an inventory of your gestalt of all of your different commitments on all the different horizons and trust your heart, or your gutters. So your pants or your spirit or whatever you trust, to make a good intuitive judgment call moment to moment about what you do. And that's it. Okay. Sorry, that'll, that'll take you two years to build that as a habit. That was a very quick explanation, even if you understand it, it's easy to understand, it takes two minutes to understand the model to about two days, if you actually were going to implement it, like literally, it literally empty everything out of your head and go through and make next action decisions about them and create an organizational structure that holds all that. And then about two years to make that habitual, so that you'd feel uncomfortable if you weren't doing it. Right.

Jason Buff 7:18

So you talk a lot about taking notes. I mean, what, in a typical day, do you just like? How do you organize all those things that are going on in your life? Or how should people try to do that to get it out of their head?

David Allen 7:32

Yeah, it's the capturing stuff is very different than organizing. So I've got, I've got notepad, right on my desk, right now has a phone number on it, I tried to call and nobody answered, or it was busy, but I gotta call them again, because they're gonna make an appointment about my eyes. So it's just on that notepad, if I if I don't finish that call that notepad by the way, they will go, they will get turned off that page and thrown into my in basket, in which case, then later on, you know, sooner than later, I will drive all that to empty by deciding, okay, where does that go? Where do I park a reminder about that, that I that I need to do. So capturing happens all day long, you know, just at any time, when in time, I you know, I carry a little notepad around in my pocket. And, you know, it's a great little app called Brain toss that I can just pop up my iPhone and talk into it, and it'll show up right into my email as a as a as a sound file, as well as, you know, text about it. Right? You know, any of that any of those things work. But, you know, I want to have the freedom to have a thought but not have to decide exactly what to do about it. Yeah, that actually allows and frees up my creative thinking process. I throw away probably half or three quarters of my notes, you know, but when I have I'm I'm not sure what they mean yet, but they might mean something significant. And so I don't want to lose any of those. But then I need to loop back around from another part of my brain and then assess that stuff and and get the executive about a call. Okay, David, what are you gonna do about that? If anything? What does that mean? That a restaurant you really want to track? Or is that a phone number that you need to put in your telephone and address? Is that something you still need to do about that? And those are the clarifying questions you need to ask yourself to decide what this stuff really means. So step one is to capture Step two is to clarify Step three is to organize the results of that thinking in that decision making. Okay, that's how that's how you get your kitchen under control by the way it looks like you know, tornado hit it you know oh my god I got guests coming over first thing you do is you recognize what's not on cruise control, you capture you identify stuff that's that you probably need to decide and do something about. Number two is you need to clarify is that still good food goes in the fridge is that trash that goes away? Does that is that dirty dish or is that clean? And then you organize those you put spices where spices go you put dirty dishes were dirty dishes go you put trash where trash goes.

Alex Ferrari 9:58

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

David Allen 10:07

Big Dog. But that's what you need to do with every email with every thought with every creative thing that pops into your head if you want to get it under control and not have it run you, right?

Jason Buff 10:18

Yeah, that's a huge thing, especially when it comes to, you know, screenwriting, and most of the writers, I know that they, and I'm also a writer, but you know, we're constantly with notebooks, because you never you, you have these ideas, and if they're gone, they you know, sometimes you're just like, you know, what, what was I, I had this amazing idea, and now it's gone, you know, and so we've gotten in the habit of taking notes. And what you know, I get a lot out of the GTD system is that you should be constantly taking notes, but about every aspect of your life so that you're not constantly in the state of being overwhelmed by thinking I've got a million things to do, I don't know what to do, I don't know what the next step is going to be. Right.

David Allen 11:01

And you obviously don't need to write down the 50,000 thoughts you have a day, you just need to write down the ones that aren't complete when you have them. There's still something I might need to do about that, as opposed to just grazing in your mind.

Jason Buff 11:16

Okay, now, what what is your feeling towards things like multitasking, or, you know, people who can kind of sit there and do like five things at the same time?

David Allen 11:27

They can't, they can rapidly switch. But whether they're actually increasing their performance by doing that is is in question. There's a couple of new books out that have come out in the last year of a lot of cognitive science research that that has basically proven, that's, you know, that's BS. And if you think your, that's going to actually increase your capability to be able to do that. Now, that said, if you can rapidly switch your focus with a placeholder, in other words, if you've sold or sort of interrupted me, Jason, you came in, and you suddenly walk out and say, Hey, David, by the way, could you do X, Y, and Z, let's talk for three minutes or whatever. And I was in the middle of doing something, as long as I have a placeholder for that thing I was doing. So I don't have to keep re remembering that I need to do that. In other words, I'll throw the notes or barbed wire work literally right into my own physical basket. And I'll turn around and then engage with you why, because I got to play somewhere that as soon as I stopped engaging with you, I can pick that right up. But that leaves my brain clear to not focus on you, and whatever's going on there, as opposed to trying to keep hanging on to it. So that's why external having an external brain and having the capability to be able to capture and placeholder stuff that's not finished, in some trusted place, will allow you to switch rapidly. If you don't do that, then you truly and they've proven this that you you do your cognitive function is sub optimal, you're trying to your switching costs are huge. In other words, you're trying to focus over there, but there's a part of you that's still hanging your focus back to where it was, that doesn't want to forget it. But then you're so you're not fully present, really, with any of that. And people can get pretty good at what it looks like. But this is a, you know, there's new, there's a lot of data out there now that that proves that's not true. They've even believe even found that that that even using hands free phones in your car is as dangerous statistically as texting, simply because of the switching costs in your mind. So you'll think you'll think you're driving in the you know, in the right lane, and the brain kind of will kid you to think that's true. And actually, that's visually what you see. But your mind went off somewhere else on that phone call that you were talking about. And it's actually that's actually not true. Surprise me to read that data. But that's the that's all that's what happens, your brain is really wasn't designed to hold on to more than about four meaningful things at once. It does that very well. By the way, that's how you survive on the savanna. That's how you can eat and not be eaten. But that rain took you know, however many millions of years it developed to be able to do that very well. So your brain can recognize brilliantly even better, way better than any computer yet. You walk into a room you recognize patterns, you see, that's a light, that's a chair, that's a person, that's a thing, that's a printer, and the computer still can't even do that yet. You're doing that all the time. By the way, your brain is brilliant at that using long term memory, pattern recognition, making sense out of your world, but it's totally present when it does that. What your brain can't do is remember where you left your keys.

Jason Buff 14:32

But you know, that was one of the really things I loved your TED talk when you were talking about how the brain has almost a you know, and correct me if this wasn't what you were saying. But the the brain's tendency to be a natural planner, to the point of or that we've kind of gotten away from the the way that the mind works, and we've started kind of changing the way that we accomplish goals in a somewhat unnatural Throw away.

David Allen 15:00

Yeah, yeah, that's fascinating. It's fascinating to realize that, that, you know, what we automatically do and how we naturally plan is not how most people actually plan the more complex things. It's how you get out of bed, how you get dressed, it's how you, you know, cook dinner. But when people didn't say, Okay, now I need to, I need to, you know, be the production manager for a movie, how do I plan? You know, how do I plan budget and all this other stuff, and you know, anything anymore? Or even just your wedding? Or how about just a big party you want to give or your next vacation. And most people, you know, either don't then plan them at all, or they're sort of driven by whatever the latest and loudest thing is, as opposed to learning from ourselves in terms of how the brain really naturally does it. It was fascinating to me, just to uncover that,

Jason Buff 15:48

Right! So if somebody's you know, sitting there today, you know, working towards a project, let's say, for example, their their ideas, they they want to produce a film. But, you know, when it comes to screenwriting, and when it comes to producing, you know, something artistic, or, you know, films are basically like a little business anyway, you know, I mean, a lot of people don't think of it like that. But so we kind of get into this abyss where you don't know what to do next. And you're starting out, and you're kind of like, okay, I know, this is the end goal. And I know kind of where I'm at right now, how do I get, you know, from point A to point B to point Z, you know, and not just like, be completely overwhelmed all the time with I have 10 million things I have to do. Yeah.

David Allen 16:36

Well, with all of it, externalizing it getting out of your head, you know, get yourself a pen and paper, just pull, you know, pull up some computer file is pull up a Word doc and just dump it out. All the ideas, every single thing you might need to think about or whatever about to film or about what your project. I mean, that's that is part of the natural planning model is once you have a vision, and it's not met met by current reality, it creates this dissonance it says with God, I got to try to get I tried to get to close the gap between the vision I have in my head and where I am right now. So there's, you know, so you do a part A with that, which is okay, any potentially relevant ID I need to capture, get out of my head. And that's what most people refer to as brainstorming. But that's, and that's, you know, that's the first thing is don't, you know, don't let your brain get constipated by, you know, oh, I got a 10 million things to do, I don't know where to start, well write down where you might start. All the places you might start, you know, as Linus Pauling said, The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas. So get them all out. Now, you don't leave them all out, just in terms of them willy nilly. You get them all out, and then there's a part of you that will then naturally start to recognize patterns and start to recognize components and sequences and priorities. Oh, that's more important than that, oh, yeah, I need to handle that, you know, first thing I really need to do is, and that's just good, sort of natural thinking. But you have to, you know, sort of go with the flow in terms of how your mind really thinks and capture that as opposed to it's got to be right before I write it down. That's death. And that's how we were taught. That's what planning was all about. If you if you know, if you're old as I am, you we were taught outlining in schools, you know, to write reports, and that's, you know, you, you sit down and start by trying to create an outline, but good luck, that that forces your mind to try to figure out what's Roman numeral one. And, you know, there's quite a bit of thinking you have to do before you even can trust what you think Roman numeral ones can be. And so giving yourself permission to have the freedom to be to use the creative aspect of who you are and how your brain works. I think that's, you know, it's our educational system that that sort of cultivated all that. But there is a way you can really make all that work. I mean, you know, come on the, you know, some of my biggest champions, were the Simpson writers. And that really, Joss Whedon, and I can talk about him because they mentioned it publicly. I mean, Josh, in Fast Company article said, Look, you know, when he when he did the last, you know, when he shot the much ado about nothing in his backyard, he said, wow, you know, if it wasn't for David Allen's next action concept, I never could have done that in the three days we did it. So, you know, and, you know, Howard Stern is a huge fan of mine really changed his life, he would tell you that he's spoken about it on you know, on the air for months, right once he wants, you know, he sort of got coached with our with our model is really freedom because what it does is it frees up space for these guys. That's that's what the creative people want. That it actually frees up space for anybody. But you know, what you do with that space is up to you. If you're a rock musician, you'll use space to get more music ideas and to make sure you finish the songs instead of just starting. You know, if you if you're a 55 year old executive that's about to merge with another company. You'll use space to be more strategic and in your negotiations and you're thinking about, you know, priorities

Alex Ferrari 19:59

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

David Allen 20:08

And if you're a writer or screenwriter or you know, if you're an indie producer, what would you do with more space? You know, there's a whole lot of things you could do with more space, I would imagine. But the space is what you need. And, you know, all GTD, the Getting Things Done modeled in bits, okay, here's how you get space. And you don't have to go very far to know where to start. Just Just ask yourself, What's on your mind? You know, Jason, if I ask you, Hey, if you if you weren't talking to me right now, what? Where would you mind go? What's the most on your mind? Right, yeah. Whatever you answer is very probably going to be something that's hung up and you're the bottleneck. The reason it's on your mind is because there's some decision about it you haven't made, or you haven't parked the results of that thinking in some, in some place your trust?

Jason Buff 20:56

Right! Yeah, I mean, I'm your, the book is pretty much for people like me, I think that, you know, I have too many things going on in my head. And, you know, it's, it's really helpful just to say, okay, you know, I went through, when you're doing the TED talk, you had the thing where you take notes, and you get all the things out of your head, that you're, that are kind of occupying your time, and then taking that and figuring out, you know, what, exactly are you going to, you know, what are the what are the next actions you're gonna take? And the really important thing, for me was the concept of what can you actually do right now, and what you're just sitting there worrying about, unless you can actually take action on it right now, there's no point in worrying about it, you know, put it in, put it there and know that you have to do it, but don't sit there and like, kind of go, you know, churn the wheels over and over thinking about that and focus on things you can do.

David Allen 21:49

Sure, there are no problems, there are only projects. So you'll only call something a problem. If you think something ought to be fixed about it, you're just not willing to figure out or take a risk to try to do that. Right, right. I mean, so taking anything that's an issue or problem that you need to decide, look, to your point, can you do something about this or not? 90% of the time, you probably can and just haven't figured that out, or you haven't sat down and force yourself to make that decision. Wait a minute, what more information do I need? Wait a minute, who do I need to talk to about this? What do I need to do to move the needle if I if I was going to pay you a million bucks, just to start making progress on that problem that issue that opportunity? Where would you go right now physically, what would you do? And that kind of rigor, you know, to your point of that the next action thinking is so powerful, it's so mundane. And yet, so, you know, it's the silver bullet.

Jason Buff 22:50

Now, one of the things that I really enjoyed about the book is also the concept of tricks. And, you know, some people now would just would refer to that as hacks. For, you know, organizing, can you talk about a few of your favorite hacks or tricks for, you know, for implementing the GTD system in your life?

David Allen 23:09

One of the best is the two minute rule. Anything you can finish, once you decide the next action, if you can actually take that action within two minutes, if you're ever going to do that action at all, do it right, then it'll take you longer to actually stack and track it and look at it again, than it would be to finish it when it's in your face. If you just did that around your house, or your apartment, or your flat or wherever you live, if you just started to implement the two minute rule, flashlight that needs a battery, it would only take you two minutes to go get that battery and stick it in there. You'd be amazed how much cleaner your house it would be if that's all you got out of what I did is the two minute rule. That's one of the most popular hacks have emerged out of all of this. Go ahead, sorry. Yeah. You know, there's, it's not really a hack. It's just it's an absolutely necessary principle, which is just write stuff down, have an in basket, have a physical injury, throw stuff in there, and then get an empty every, you know, 24 to 48 hours. I mean, that there's there's no bigger, better habit. People say, Gee, David, what rituals and habits have I installed that's laid the main one. You know, there's all kinds of stuff I hate to have to think about and have to decide about. But because I'm so now addicted to getting my in basket empty, it forces me to make those decisions so I can empty it. It's one of the best, that's one of the best tricks in the world, in terms of being productive, because people just avoid next action decisions about all kinds of things. So they just spread stuff around in their life. And then it starts to create this ambient stress, because it's yelling at them all the time. And they just no mouth to it.

Jason Buff 24:48

Now, can you just go a little bit more in depth with the next action concept? Just for a second?

David Allen 24:55

Yeah, well, you know, write everything down that's on your mind. Alright, then take each one of those things. One at a time ago, okay? If this is something to move on at all, it may have been just a harebrained idea or something else. But is there something to do about this? What specifically physically visible action would would I need to take to start moving toward closure on whatever this thing is? If it's if you wrote down cat food, what's your next action? Oh, I need to buy cat food. Or Great. Do you know where to buy it? Yeah, I do. Where they do you keep a list of stuff to buy when you go there? Yeah, right up on the fridge. Great. Go stick it there. Cat food on the posted on the refrigerator and now you're in then it's off your mind? Some fournisseurs. Okay, did that. But you have to decide what's the next step on that. Okay. Okay. New indie movie idea. Fabulous. What's the next action? Oh? Well, I don't even not sure how to start. How would you figure it out? You know, I want to talk to somebody who actually produced it in the field. I have never done one before. And I should talk to him. Great. How would you? How would you plumb their brain? Maybe we should have lunch for them. Great. What's your next action? Set up a lunch? How would you do that? Send an email to send their phone call to me. Let me let me shoot him an email. Great. How long would that take? 30 seconds go. Suddenly, you know, suddenly you're off and running. But you still haven't the foggiest idea how to do an ad, you just made a decision that got you in the driver's seat of this situation, as opposed to feeling the victim of now over committing and having a beat you up.

Jason Buff 26:35

Yeah, and it's so simple. But it actually I mean, it does completely change everything. You start thinking like that.

David Allen 26:41

I call it the magic of the mundane.

Jason Buff 26:46

Do you actually have a Do you have to have a physical exam? I mean, you talk about your in basket and you know, everything that I do if I have papers, it just becomes out of control here. You know, I do everything virtual but you think it's it's better to have physical there.

David Allen 27:01

You still have a physical driver's license. You still you still get some bills in the mail, you certainly get certain some physical mail you get FedEx, it's

Jason Buff 27:10

Not well, I'm an expat like you. I live in. I live in Mexico. So you know, we don't get mail where I live, but I get your point.

David Allen 27:19

Yeah, but you know, believe it or not, there's a lot of stuff that I need to print out from my computer and throw it into my in basket, because there's stuff that I need to do or think about that. And I want to I want to have a written, you know, thing to that helps me think about it, you know, or I'm halfway through something, and I need to remind myself that that's not finished yet. And I need to come back to and I'll print it out and throw it in my in basket, which then is a trigger to then oh, yeah, let me pick that up and keep going with that. Certainly a lot less paper now than there was, you know, 20 30 years ago for sure. Right? But even even so, you know, where do you throw back, you get flashlights that get dead batteries. I throw those in my own basket, if I don't have the batteries in anything. And if you take any kind of notes when you're on the run, what do you do with if you're doing any kind of creative writing by hand? You know, what do you do with those notes? You know, and if you're taking notes on a phone call, right? You ever do that? Yeah. Yeah. What do you do with those notes?

Jason Buff 28:27

Well, I just usually I just use Evernote. So I'm just I type faster than I write. But I've also got a, you know, a notebook. Whenever I go to a store, I just buy like five or six notebooks and just have just have it there, you know, because you'll you'll be able to jot stuff down.

David Allen 28:42

Well, you know, if I were to sit down next to you, deskside you know, Jason, we'd I'd say, I'd say Do you still have bigger those notebooks? Probably not. Well, that's fine. It means you process them. That'd be my point. If you still had them lying around, because there was still stuff in there that you hadn't decided what it meant. And it was still potentially pulling on you to make a decision about it. You know, that's that's unhealthy. spiral notebooks are dangerous, you know, because of that. I use a spiral notebook, but I use one that's perfect. So you can I saw I tear it off so it stays empty. Yeah, you know, but the stuff I tear off goes into my in basket if it's if it's if I can't finish it in that moment. So I still need a physical basket if you can get by with that one. They but there's no there's no right or wrong about any of this. It says okay, got anything in your head. And if you do, there's some because of some something you have not captured somewhere.

Jason Buff 29:42

Now when you say you've got it in your head, I mean, like subconscious thought I was wondering how you feel about like your subconscious thought.

Alex Ferrari 29:51

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Jason Buff 29:59

So how is that affecting you? I mean, are you are the things that are in your head, like, you know, if you've got like 20 things that you're kind of like organizing, trying to keep track of? Are you conscious that you're doing that? Or is that something that you're just kind of doing? And it's affecting, you know, just your mental, you know, alertness or being able to be present?

David Allen 30:23

I'm not sure exactly. Obviously, if it's unconscious, you're not conscious of it. I'm not aware. So. But essentially what I do, because I've externalized all of these commitments, then it frees me up to just trust me intuitive judgments. And that intuitive judgment is being matured and constantly, I'm thinking all the time, I'm constantly reassessing, what should I do? Where's the thing? Where what do I feel, you know, like, I need to put my energy and focus right now, you know, that my system doesn't get rid of that it frees you up to do that frees you up to be making good intuitive choices, instead of just being driven by the latest and loudest, and then Lipson and hoping you know, so you want to move from hope to trust basically, in terms of you just your judgement about what you're doing. But um, you know, I'm constantly thinking of what should I do now? When Where's where's the? Where's the optimal place for me? Should I take a nap? Should I have a beer? Should I? Should I go hang out with my dog? Do I need to take a walk? You know, should I be, you know, cranking on this, you know, slide deck that I need to upgrade right now. So I don't know, if it's your unconscious, I think that I think you don't have to go very far just to start to pay attention to what has your attention? What do you then need to do to take that pressure off your head? You know, what's the next thing that should be telling you what to do the weather that's coming where that comes from, you know, the Oracle or God or, or your your liver or I don't know, whatever the source of intuitive knowing is, you know, who knows. So this is about about, you know, sort of structuring your life in some ways. Matter of fact, a lot of people are uncomfortable with how unstructured getting things done is because they want to feel more confidence that they that they really nailed it all down and can and can tack it all down and nothing's gonna move, you know, and come out from under them. Good luck.

Jason Buff 32:14

With that, that was what I was going to ask you about, you know, that, that you talked about the false sense of control that you get from, you know, having everything in your head, and there is that aspect of control? That I mean, that's counter that resistance that people are just like, oh, I don't want to, you know, I don't want to stop having all this some, I don't want to put it on a piece of paper. Because that might mean that something might happen to it. Or it might you know,

David Allen 32:39

You'll make that happen, you'll make you feel more out of control about how out of control you really are. That people get mad at me for their list. I go excuse me, it ain't my list, dude. It's yours. You know, your choices? Where do you want to track that stuff? And I just, and I'm not into convincing anybody, I'm just look, I'm just sharing information with you. Right? And prove me wrong, implement these processes. And I absolutely guarantee you without fail, you'll feel more in control and more focused, so that you can deal with that and have more mental and cognitive space to do the more meaningful things.

Jason Buff 33:18

How did how did you go upon? How did you come upon this? I mean, when you have in your life, where you also kind of just like one of the people that was overwhelmed with stuff and had to I mean, how did you discover this system?

David Allen 33:30

Ah, I've just been a, you know, I'm a freedom guy. And I love I love ClearSpace. Right? I've always been attracted to the Zen aesthetic, you know, sort of the negative space, or, you know, I was I read all of Suzuki and watts, by the time I'm finished high school. So I've always loved that kind of minimalist aesthetic. But then, you know, when I got into sort of the personal growth game, and you know, how do you grow yourselves? And how do you find enlightenment and all that good stuff, you know, this is California in the 60s and 70s. and discovered that actually, there are things you can actually learn to do that actually give you more of a sense of personal freedom, and more of a sense of space, and a whole lot that had to do with your agreements. You know, that was a big aha, in the personal growth loop, which was, you know, how do you manage your agreements, and what's the price you pay? If you break an agreement?

Jason Buff 34:22

Then what do you mean by agreement?

David Allen 34:24

Well, if you just said compromises, you know, the agreement, you make call Hey, David, let's meet at you know, let's do this podcast on you know, this date this time. That's an agreement. I say, Yeah, I just made an agreement. An agreement just says any commitments, you've got to do something whether an all agreements or with yourself, many of them involve other people, but they're all with yourself. You've agreed with yourself, you're gonna do that. You tell yourself I need cat food gets me in an agreement. You know, yeah, I just agreed with myself that yes, I'm going to get cat food somehow in some way. So understanding that When you keep an agreement feels fabulous improves your self confidence. If you break an agreement, they will undermine your self confidence automatically. It's an automatic price you pay that you disintegrate trust. If you didn't show up, you know, or if you you know, there are people I love dearly, but I don't trust for them, and I can throw them to show up, when they're going to tell me they're going to show up just based upon that, because nothing wrong. I don't judge that I just that's just data. But I don't trust them. I don't trust them to keep to, you know, they tell me something, I doubt they're going to do it and shouldn't organize my life accordingly. But but they're all of these agreements with yourself, what happens then, if a broken agreement automatically creates stress. So all those things you've told yourself to do, and most people have between 30 and 100 projects, and between 150 and 200. Next actions, if they actually sat down and truly inventoried their commitments personally and professionally, while the things they think they should do and told themselves they they need to do. So if you want to get rid of the stress of broken agreements, either don't make the agreement, don't throw the list away, say, oh, you know, I'll live spontaneously, you know, good luck. or complete the agreement, go finish it all. Of course, if he went and finished everything on your list in two, three days, you'd have a bigger list because you get so excited having done all that you'll take on bigger, more incomplete stuff. But the real key is, how do I how do I kind of renegotiate those agreements? See if you said, Hey, David, let's do this podcast here. And then I came back said, you know, I agreed to that before, but something came up really, really critical that I have to handle can we do it another time? And you go, yeah, then I renegotiated the agreement, I don't have a broken agreement. But you can't renegotiate agreements with yourself, you can't remember you made that's again, why keeping track of all of this stuff, so that you can look at it and go, No, I'm just gonna do this podcast with Jason right now. That's the best thing to be doing. But the only reason I can be present talking to you right now is because not long ago, I looked at everything else that I might would could should ought to do and said yet. But I couldn't I can't do that in my head. I could remember about four things. And that's about it. Everything else just becomes this huge jumble and jungle. But once I've got them out and have all these decisions made about the actions and just all I have to do is plan for those Action Lists, look at my calendar doesn't take very long, and just feel comfortable that this is it. Nothing, I'm not missing anything. Now I may I may have made a mistake, you know, maybe talking to you is the wrong thing to do. And I'll find out live and learn. But at least I'm confident that this is the next mistake I want to make.

Jason Buff 37:36

That makes sense. Yeah, definitely. Now, you mentioned Howard Stern. And I know Howard Stern's a really big into Transcendental Meditation. And a lot of this seems to be influenced by Eastern thought. Was that something

David Allen 37:51

Eastern thought just came up with the same thoughts I did.

Jason Buff 37:57

They all read your book, you know. mean, just the concept of you know, meditating and emptying your mind in that way. And being present. And you even mentioned in your book, the mind like water? Concept?

David Allen 38:13

Yeah. Well, you know, that was I had, you know, several years in the martial arts, you know, and got a black belt many years ago and in karate, and there's, there's quite a bit of training about how do you clear your head in the martial arts, Bruce Lee was the guy who was sort of made famous, this whole idea of be like water or grasshopper from his guru, because, you know, the idea is don't over under react to be totally open to the to the present moment, you know, be soft and hard as needed be, don't over under react. And that's, that's the idea is that you don't want to take one meeting into the next you don't want to take home to work. You want to be able to be present, really, the whole idea of GTD is about being present, that's your optimal productive state, whether that's the best way to hit a golf ball or tuck your kids into bed at night, or make spaghetti. You just want to be there when you're doing it. As opposed to having your your cognitive function split. So that's, in a way, this is just a mechanical process. It's not something to believe it's not something it's not some cognitive thing, go. Look, the brain sciences is now validated all of this. And it took me 35 years and learning it on the street and watching spending 1000s of hours with some of the best and brightest and sharpest people on the planet and busiest and watching what happened when they started to implement this and how much it changed their life and their work without exception. So that's why I wrote the book because I think it's a better right manual.

Jason Buff 39:44

Now what what were the Are there any books you can aside from your own book? Are there any books that were out there that influenced you and you could recommend as well or any resources out there that people could look

David Allen 39:56

There were there were a lot of them over the years I you know I

Alex Ferrari 40:00

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

David Allen 40:09

One great book, by the way for especially for creative types would be Steven Pressfield. Book. The War of Art. Oh, yeah. Yeah, that's a great one fabulous book. And that's what and the two I mentioned, by the way, if anybody's interested in the cognitive science stuff, I mean, it really is quite fascinating. And to have shown up in the last few months, one's called the, the organized mind, by Dan Lemington, le VI, ti n. He's head of cognitive science research at McGill University in Quebec, or wherever in Canada, that is, and a Belgian named Theo Compernolle, Compernolle has just written a book called Brain chains to words like chains around your brain brain chains. And, you know, he's he, he was a child psychiatrist, and then an MD, and then I got into cognitive science. And that has been, he's doing quite a bit of executive coaching in terms of stress management, simply because he became fascinated with this whole idea of the brain as a tool. And he's, he's accumulated aggregated, 600 different studies, from the cognitive science field and world in the last decade or so. And, you know, and kind of reads the riot act, everybody about multitasking, and what the digital world and social media and so forth are, are the addiction that that's making so easy for people to get invested in and engaged in, that's been stopping a lot of other you know, real cool stuff, like real conversations and real relationships. And he's got a he's not against technology, he just saying, be careful, because this is highly addictive, and that they've now proven it love truly is an addiction. That if you if you're if your social media, even just having your your smartphone in your pocket, wondering, who's texting you creates a dopamine rush. So you literally are getting the same kinds of things that you do with an opium or heroin.

Jason Buff 42:23

Right, it seems like, you know, the older I get, the more I realized that my life is determined by the little things that give me a little dopamine rush, you know, like, the career that you choose, and the people that you are around and all the little thing, you know, even the the color of paint that you choose in your house or whatever, it's like everything is determined by the that little rush you get from it.

David Allen 42:45

There's nothing wrong with that. I mean, exercise does that so you can't fault exercise. Which is which? Which are the healthier dopamine rushes, you know, what do you want to get addicted to, you want to get addicted to working out, you want to get addicted to, you know, you know, in Fetta means, right.

Jason Buff 43:06

I also like the idea of, you know, you were talking about how you, you want to write stuff down because your future self is not going to be in the same state of mind that you're in. And always, you know, you always need to be somewhat aware of, you know, how your brain changes from maybe one time of day to another time of day, or how you're in a certain kind of state of mind, where you're being very creative and coming up with ideas and appreciate the fact that maybe later on in the day, or maybe whenever that's gonna kind of disappear. And you're leaving kind of like future notes or like, note to future yourself, you know, because it's funny, I had a friend who would go out and drink a lot. And he would always leave himself voice messages. And he would wake up the next day and be like, Okay, what, what's going on? And he'd be like, Dear future, Mike. This is what's smart today.

David Allen 43:59

Welcome, you know, I think it's really intelligent people that realize they're only inspired, and Intel, and then you're only inspired and brilliant, you know, at very random moments in your life. And, you know, so what you want to do is if you're lazy and smart, what you want to do is capture those potentially useful, inspirational intelligent things. So that when you're kind of thick and dumb, you do smart things. So you know that yeah, it's the it's the kind of thick and dumb people that think they're smart all the time. The strange thing is, is that when you are inspired and have an inspired thought that that place that that we seem to operate from there has no sense of space and time you're in your zone. So it doesn't it's not kind of that consciousness is not so well aware of history, or future. It thinks it thinks you'll be inspired and smart all the time. So it isn't was intelligent of your friend to realize, hey, when I'm in school I heard the future me may not be so inspired. So I better grab that and throw it at him. Yeah.

Jason Buff 45:09

I'm always surprised if I go back and look at my notes. Sometimes I came up with, like, you know, I write every day I write in the morning. And that's like, when I'm focused coffees going and everything. And I always shot, you know, I go back sometimes. And I'm like, Yeah, I remember everything that I wrote down, and I'll go back and see those notes. And it's like, oh, wow, that was a really great idea. But I just, you know, for whatever reason, it wasn't there anymore. You know, the, my ability to recall it just had gone away. So can I want to wrap it up? Because I know you, you know, have things to do? Can you just talking to people who are out there? In our audience, it's filmmakers and screenwriters and people who are working on projects? Can you you know, what do you think, is a good idea for them to start doing what can they do today to really start moving forward and not being frustrated and getting their projects, you know, on the road to being, you know, completed?

David Allen 46:05

Well, come on, I would be remiss and not saying get my new version of getting things done. And read it, if you haven't yet. I mean, it truly it is the manual for all of that, and then we'll, it will be pretty evergreen for lots of years to come in terms of, you know, what we've uncovered and what we've discovered about it. So that's, that's essentially a, you know, a great resource. That's, that is a way that is a way to start. But quite frankly, it just make sure you've got some, you know, the take up, you might want to take a few hours. At some point, if you can carve that out of your life, and say, Okay, I'm gonna do this dumb thing called sit down and write down every single thing that's on my mind. You know, anything about anything, you know, little things, big things, personal things, professional things, creative things, anything and truly keep going. You know, most people can do that in about an hour or two leashing get most of it. And then, you know, go through each one of those and say, Okay, what is exactly my next action? On this? What's my next action on that? What's my next action on that? So just capturing, and then applying the sort of next action, cognitive rigor to these things? And then you're gonna have to, then you'll have to get creative to decide what do I want to do? If I can't take that action right now? Where do I want to park? And how do I create a list? How do I create some sort of organizational system, if you don't have one already, you'd need to then go through that process. So ideally, you you know, set up a whole day, get my book, because I actually walk people through this exercise, you know, blow by blow part in part two of the book. That's one of the reasons I wrote it that way, so that people didn't have to hire a coach to walk them through this. But you're not born doing this. And it doesn't come, you know, automatically, you actually have to sit down and put cognitive horsepower to this game. And it does take an investment on the front end, doesn't take a lot of time and energy to maintain it. As a matter of fact, it's much less than what most people are trying to do once you actually get this setup, but it does take an investment on the front end.

Jason Buff 48:07

Well, David, I really appreciate it. Thank you so much for coming on the show. It's a pleasure to have you here with us today.

David Allen 48:15

Hey, it was fun. Jason was great.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

LINKS

- David Allen – Official Site

- Read David Allen’s books

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Filmmaking or Screenwriting Audiobook