You’ve just boarded a plane. You’ve loaded your phone with your favorite podcasts, but before you can pop in your earbuds, disaster strikes: The guy in the next seat starts telling you all about something crazy that happened to him–in great detail. This is the unwelcome storyteller trying to convince a reluctant audience to care about his story.

We all hate that guy, right? But when you tell a story (any kind of story: a novel, a memoir, a screenplay, a stage play, a comic, or even a cover letter), you become an unwelcome storyteller.

So how can you write a story that audiences will embrace? The answer is simple: Remember what it feels like to be that jaded audience. Tell the story that would win you over, even if you don’t want to hear it.

Today’s guest Matt Bird can help you. He is a screenwriter and the author of the best-selling book The Secrets of Story: Innovative Tools for Perfecting Your Fiction and Captivating Readers.

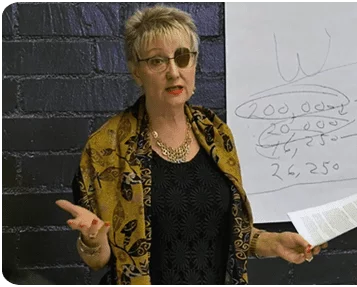

The Secrets of Story provides comprehensive, audience-focused strategies for becoming a master storyteller. Armed with the Ultimate Story Checklist, you can improve every aspect of your fiction writing with incisive questions like these:

• Concept: Is the one-sentence description of your story uniquely appealing?

• Character: Can your audience identify with your hero?

• Structure and Plot: Is your story ruled by human nature?

• Scene Work: Does each scene advance the plot and reveal character through emotional reactions?

• Dialogue: Is your characters’ dialogue infused with distinct personality traits and speech patterns based on their lives and backgrounds?

• Tone: Are you subtly setting, resetting, and upsetting expectations?

• Theme: Are you using multiple ironies throughout the story to create meaning?

To succeed in fiction and film, you must work on every aspect of your craft and satisfy your audience. Do both–and so much more–with The Secrets of Story.

I dig into Matt’s story system and break down the secrets of the story. Enjoy my conversation with Matt Bird.

Alex Ferrari 0:09

I'd like to welcome to the show Matthew Bird, Matt. How you doing my friend?

Matt Bird 3:33

I'm fine. How are you?

Alex Ferrari 3:34

I'm good man. Just live in the quarantine life, sir. Live in the quarantine life.

Matt Bird 3:39

It is crazy. This is absolutely insane. It's it's hard to read. You have to remind you every will every morning. I've always had sort of apocalyptic dreams. And then I wake up in the morning and I'm like, oh, it's apocalypse. The apocalypse. I'm like, Oh no, it was a dream. I was just dreaming. It's my normal life. And now I've been waking up every morning going like, oh, it's the apocalypse apocalypse. Like no, that's just a dream. I'm like, no, no, it's not. It's not a dream. This is the apocalypse is happening. I can't shake this one off.

Alex Ferrari 4:05

No, I heard the other days like can we put 2020 in a bowl of rice to see if it could fix it or something? Because it's I mean, this is an insane insane year and we're not even halfway through yet. So as of this recording, so buckle in, see what happens but but we're here today to talk about story and I wanted to first before we get into your book and and your concepts and what you teach. How did you get started in the film industry? Because I think you had your origins in the film industry.

Matt Bird 4:41

Yeah, sure. I was always making films and I was I considered myself sort of like a punk DIY filmmaker back in the day like and I was always like working with the stuff that had just come out so I worked with a little bit with to braid and then when DV when mini DV came out, I was like this is great. I can make my own movie I made a feature film. What at first That's not that's not even true for me to feature film. That was the thing. I was always I love features I never, I was like I forget shorts, I'm gonna put in the work, I made a feature on sbhs when I was in high school, or when I was in college, and then when I was out of college, I made a feature on mini DV. And I shot it having no idea how I was going to edit it, because there was no editing software at the time, right. And then right as I finished production that came up with Final Cut Pro 1.0. And I was like, I'm gonna buy it, the first day it hits the store, and I was first community who had figured out this program, which was insane program. And then I've made a feature there. And I was just doing, I was doing whatever I could and then eventually I was like, Okay, it's time to get serious. I went to film school, I went to Columbia University, film school, and I spent a fortune that I did not have a fortune that I may never have, I'm still paying off my loans. But I went ahead and I mean, sometimes there, I shifted my focus there to screenwriting, which I think was wise, I won some awards, I was, you know, they, they basically announced at the end of every year at Columbia, we are going to pick 10 students who we are going to push as you know, people who we're gonna try to help get representation and sales and everything and the other 70 Kids are cut loose. We're not gonna help you guys, but we're gonna help you send kids. So thankfully, I was one of the 10 they, you know, I took a bunch of meetings, New York, and La got a very big deal manager was, you know, got just a few gigs. I was hired to do an adaptation of novel and that went, Okay, I was I set up, you know, I, in screenwriting, it's all about setting up, like, Oh, my God, I've had such a test. As a screenwriter, I've set up this project here, and I've set up this project here. And I've set up this project here. And I'm working with this person, and this person and this person, give her like, oh, how much did you make? Oh, nothing. Like, oh, no, no, the money, the money. That's all that's a bank account, that money is being always money is being held back by a dam, right in front of me. And but it set up. So that means that there's cracks in the dam, and the whole thing is about to flood. And don't you worry. And then eventually, I decided, you know, it wasn't the unsuccessful projects that killed me it was the successful projects, it was the ones where I got paid. And I was like, I can't stand being treated the way I'm being treated. And I can't stand, you know, just, I've just wasn't built for it. I just wasn't built for it. And then I started and then I got really sick. So that didn't help. And by the time I was better than all my heat was off me I was no longer getting meetings, and I started a blog. And at first it was just a rewatching movies blog, or an underrated movies blog. And then I couldn't, I eventually got to a point where it's like I was, you know, this isn't the heyday of blogging in 2010. So it's like, I have to watch a movie and blog about it every day. And I'm like, this is gonna kill me. And so I should start just giving writing advice as an excuse to give myself a day off. Like, instead of doing something hard today, I'll just write some writing advice. And soon that just that just built up and built up and built up. And people were like, Matt, all the stuff you've done your life. This is, this is your passion. This is what you're really good at, you're really good at giving writing advice, and you're into a book and you should do this and that. So soon I turned into a book, it was the secret, some story published by Writer's Digest. I started doing manuscript consultation, I started doing all that. And it became very big, you know, the book became an Amazon bestseller. It was, you know, I've now got the secret straight podcast of the Secret Story YouTube channel. And it's been wonderful. It's, you know, you never end up where you think you're going to end up. But this is turned out to be my passion. It's turned out to be what I'm good at. And it's been great.

Alex Ferrari 8:48

It's been your your own hero's journey, if you will, sir.

Matt Bird 8:52

It's been pretty much my hero's journey. I mean, if you in my book I talk about, you know, the great talking about stories about when I got sick, and when, you know, it was I found myself ironically living out these heroic narratives that I was learning about and trying to write about, and it'll end up being deeply ironic, but I wound up coming out on top. So maybe not on top. I can't, you know, somewhere

Alex Ferrari 9:17

above water, above a water above the water, the water. Now in your book, you talk about the 13 laws of writing for strangers, which is a just a great writing for strangers is a great idea because that's what we do. Basically screenwriters you write for strangers, generally speaking a lesser, Chris Nolan. And even then you're still writing for strangers because someone else is financing it. So you have 13 laws. Can you talk a little bit about a few of them?

Matt Bird 9:43

Yeah. Let me see. How I go. You know, I wrote this book five years ago, who knows what the rules were. Okay. So the number one was screenwriting. Well, I should say no, the number one wants story. This is for all kinds of story writers. You must write for an audience, not just yourself. Because I think a lot of people, I think the worst piece of advice people get is like, oh, you know, tell a story that you love. And then it'll be a great story. It's like, I don't know about you. But when I was a screenwriter, I loved all my stories, like it was, that was a very low bar, trying to get a write a story that I love, I would write it, I would love it, I would send it out into the world. And a vision, everybody's like, Oh, right, I'm not just writing for myself. I'm writing for other people. I am writing for strangers. And I have to figure out what a stranger wants. And guess what strangers have a lot higher standards than you have for yourself. And some people are really, really hard on themselves. And they're like, you know, you know, like, Miles Davis had a quote something like, you know, like, I, I'm the toughest audience there could possibly be, so I can please myself, I know, it must be great. But I'm not Miles Davis. And I was that hard on myself. And it was only when I realized, okay, I'm writing for strangers. I'm writing an audience writing for an audience, not just for myself. Why? Number two is audiences purchase your work based on the concept, but they embrace it, because of your characters. I think this is, you know, we tend to overvalue a concept. Concept. We're like, Oh, my God concept, it's gonna sell itself, it's gonna write itself. Like, no, it never writes itself. And it's probably not going to sell itself either. Like, yes, people are gonna want to hear you have a haircut. So if they're like, they're like, that's great concept. Now, have you read it. And then as soon as they read it, they do not care about the high concept. They do not care about any of your big ideas about your big concept. All people care about, and they're going to give you five pages. And they're going to read five pages, which road and then like, do I fall in love with this character. And if you do follow the character, and then you never get around to delivering that high concept you promise, they won't even notice. They're like, Oh, I don't really have that concept anymore. Give me a character I love. I'll go anywhere with him. Give me a character I don't love. Forget it. Even if it's the best, hottest, most wonderful idea in the world. Forget it, I'm not going to read it. So that's one, number two. Number three, audiences will always choose one character to be their hero. I feel like this is people a lot of times are like, well, you know, do you think one person see her for the first 10 pages, and then I kill him off. And then you're gonna think that someone else is there for the next 30 pages. And then you realize, now now, it's really that person in the background. Now, of course, you can always think of exceptions. Alien is the ultimate exception. You have no idea who the hero of alien is, until you're about 40 minutes into that movie. And suddenly, you're like, wait a second, that woman in the background. She's the hero of the story. Like I thought the hero was Tom Skerritt who just got killed off. But that is a huge exception. And usually, you're gonna want to convince you know, your the hardest part of writing is getting people to go like, I am invested in this character. And I'm going to follow this character through the whole story. And if you want to write in, that's fine. If you want to convince people to invest in one character, and then kill like a drug, and then go like, no, no, no, I'm gonna convince you to care about a whole nother character. You can try it, but doesn't tend to work.

Alex Ferrari 12:55

It's funny. It's funny, when you were saying when you're talking about like going with a character on a ride, you read, you watch Raiders of the Lost Ark. And you're introduced to indie. And if I remember, there was no dialogue or like a minimal dialogue, all throughout that first part up all up until almost none, I think he had maybe one or two lines. And that was it. Until the until the boulder came down. And after that sequence, you you were in like, you have no idea his backstory, you have no idea what he like, all you know is like, I wherever he goes, I want to follow him. Because this is awesome.

Matt Bird 13:37

Because he's doing awesome stuff. He's got a whip. I mean, he has a whip, the whip for all kinds of stuff. And then he gets, he does awesome stuff. But he fails and he gets humiliated. It's not about him being an awesome badass, you know, it's not like, hey, you know, here I am with the idol. And that proves how awesome I am. I just recovered this idol. Now we love Him because He does all this awesome stuff, get the idol and then fails to get the idol. And he fails in a way that prefigures the whole movie. What I mean? First one was how does he really fail? He fails because he's like, Well, I've got an idol. And I've got a bag of sand and a bag of sand in the idle way, the exact same amount. So if I switch out the handle for the bag of sand, they're the same thing. And of course, what's he doing is he does not realize the power of faith. He does not realize that, you know, there is a religious value to this idol that the bag of sand does not have. And because he is blind to the religious value, he almost gets killed. He almost gets run over by a boulder because he cannot tell the difference between a religious I don't want a bag of sand and then that takes you right through the end of the movie where it's like he finally at the end of the movie. He says close your eyes Marian because he realizes that you know Oh, this isn't just the ark. It's not just a bag of sand. The Ark is a religious thing and now God is going to rain vengeance down and melt that guy's skin and turned into milk. And that is that is it's one of the most brilliant openings movie ever. Yes, without question, but see. So it seems small. Number four, audiences don't care about stories, they only hear about characters. What number five, the best way to introduce every element of your story is from your heroes point of view. Again, lots of exceptions. I love the exceptions, some of my favorite movies or exceptions. But man, if you can just get people to care about your hero, then we'll care about what your hero cares about. And if we don't care about your hero, or if your hero doesn't care about the story, that's one of the worst mistakes you can make is like, oh, you know, my hero has a lot of onwy. And he is not invested in the story. The story is sort of going on over his shoulder, we're sort of peeking around his head going like, hey, heroes, there's a whole story going on back there, pay attention to it, and the hero doesn't care. It's the worst one. And it's very hard to get audiences to care about any hero because they're afraid of getting hurt. I think this is this was one of the big ones for me, when I realized this, it's that audiences, if you were writing the very first story anyone had ever written if you're a caveman, and you're like, I've just invented this concept of storytelling. People are like, Oh, well, that's fascinating. Tell me more. But as it is, people have spent their whole lives reading books, watching movies, and most of them have been bad. And every time people read a bad book, or watch a bad movie, then it hurts, it's painful to read a bad book, it's painful to watch a bad movie. Because though a story asks you to care, a three asks you to invest your emotion, Noah's story is not just something that you passively stare at, you're not just sitting in the theater going like, well, I could look at any one of these four walls, but I'm gonna have a look at the wall that has the pictures moving on it, you are getting sucked in, you are being asked to care. And usually you're being asked to care about a useless hero going on an uninteresting story. And you know, I wouldn't say most of the time, but a tremendous amount. A tremendous amount of stories are bad. And what do you say, when you see a bad movie or read a bad book, you say, Well, I'm never doing that, again, you say I was tricked into caring about this hero, and then he turned out not to be worth caring about. So I'm not going to care again. So every time you write a book, or you write a screenplay, or you make a movie, then your audience is people going to be like, first of all, I know, this is all wise, you're not going to trick me into thinking this is a real person, right? And then you're not going to get me to care. There's no way I'm gonna care about this person, because you're just going to hurt me, I don't wanna be hurt again. And so that is a huge hurdle you have to overcome is realizing that getting the audience to care is going to be the hardest thing in the world. Or number seven is, your audience need not always sympathize with your hero, but they must always empathize with your hero. So I talked about how like, you know, we, when we were in film school, it was like the heyday of Mad Men and The Sopranos and Breaking Bad. And they were like, Oh, these heroes aren't sympathetic. So that means these are successful here with neon sympathetic semi Do you no longer have to write sympathetic heroes anymore. So that means you can just write about anybody, and you can write any story you want to do, and they can just be the most loathsome hero in the world. And people have no choice. Now they have to care about it, though the whole rules have been thrown out the window, we did not realize how hard these writers were working. First of all, we didn't realize that all of these writers had gotten their starts on shows where you cared very much where the hero was very sympathetic. So for instance, did you know

David Chase, who created the sopranos, he had gotten a start as a writer on The Rockford Files. There has never been a more lovable hero in the history of TV than Jim Rockford on The Rockford Files. And so he knew he was not somebody coming along going, like, Gee, I don't know how to create a synthetic hero. So I'd better create a yeah, I'd better create Tony Soprano instead and create an unsympathetic hero. And, you know, hopefully people will like him. No, he knew how to create sympathetic heroes, and he knew how to get us to love Tony Soprano, even though he was an awful guy. And he knew it was because we wouldn't sympathize with them, but we would empathize with him, we deeply empathize with him. And that's why your story about a sympathetic ear. That's why people are saying, Oh, I hate your story. Because it's an unsympathetic hero and you're like, but But what about all these unsympathetic heroes out there who are great heroes, when they're really mean to say is not that they can sympathize with the hero, they're saying, I can't empathize with your hero. And that is death. That is you can have the least sympathetic ear on the world, but if we can't empathize with him or her, forget it.

Alex Ferrari 19:21

So then you look at a character, which arguably, I think is arguably one of the best television shows of all time is Breaking Bad with Walter White. I mean, his transformation from like, like, I'm gonna Gillean Vince Gilligan said he's like, Mr. Chips turns into Scarface, and, and you know, when I started watching that show, it's it just, you see him slowly turn into a monster, but yet he turned into a monster for the like when he started the journey. It was for kind of the right reasons. Kind of it's a gray area. Have you want to say the cell math, but I get it, I get it. But then afterwards, it stopped being about that. And it was all about his own ego and he literally turned into a monster. But yet you still were empathetic with him. Like it was so brilliantly written and performed as well.

Matt Bird 20:17

Yeah, if they had, I don't I don't know if they had gotten they originally offered the show to both Matthew Broderick and John CUSEC. And I don't know if Broderick in case I could have pulled it off. I don't know if we would have you know, we would have cared as much about Matthew Broderick or junkies, I could say had gone on that journey. It was really it was all about, you know, don't get me wrong. Vince Gilligan scripts were amazing. They were insane. They were brilliant. And Better Call Saul is still brilliant. I'm I'm watching the most recent season that right now. But, you know, Bryan Cranston, come on? I mean, so good on that show, he made that show. He was amazing on that show. And it was so good. But no, I mean, you know, I mean, if what might have happened sick, you know, if he had not been, you know, it was so important that he had been sick, it was so important that he had been screwed out of his previous job. I think that, you know, the best motivation. It's like, how, first of all, once you got to the point where Walter White had made an insane amount of money. And, you know, obviously, it got harder to empathize with him as the show went on. Because he had was, he was no longer sick. First of all, he had, he was no longer conceivably doing this for his family, because his family now was, you know, his wife had found out and hated him for doing it. So, you know, in order to make his wife happy, that was it. But the real, I think the hidden motivation on that show that made it that didn't justify but strongly motivated all his actions, is that he felt he had been cheated out of a billion dollars. He felt that when he had been forced out of this company, right, that he had, I think greymatter was the name of the company. And he, he felt like he had this burning resentment inside him from feeling like I was part of a billion dollar startup. And then I was forced out. And I was cheated out of this money. And so that gave him the bottomless pit. Because, you know, in the end, the illness wasn't abundant was paid for, you know, trying to trying to satisfy his family wasn't one was bad. It was that resentment of feeling like I and I think so many of us feel that way. So many of us have, like, you know, like, that was my fortune, you've got my fortune. We all have that person. We know, who made it when we didn't make it, and who she was out of the thing. And it was, I think that is one of the most underrated or underrecognized elements of that show of why people love that show so much.

Alex Ferrari 22:37

Yeah, and it's still it's still going. It's still going and it'll go on and it ended. It had a beautiful one of the most beautiful endings to a show ever. So brilliantly, brilliantly done. Did you happen to see the Colombian version of Breaking Bad?

Matt Bird 22:54

No, there's the Colombian version there is that they literally took

Alex Ferrari 22:57

the scripts and test translated them into Spanish. And then they licensed it. And they licensed it to a Colombian set of actors, and they did everything down there in Colombia, and it's a telenovela. Basically, they made it into a telenovela. If you want, if you can get just a few if anyone out there, if you can send it to us somewhere online. Right, Bradbury. He saw one of

Matt Bird 23:22

my favorite TV shows, one of my favorite TV shows of all time is slings and arrows about life in a Canadian Shakespeare Festival, which doesn't sound like it would be a great show. But and then I found out that the director of City of God, yeah, made and, and oh, and he just made another film that was really great. But the director of city Oh, God made a Brazilian version of slings and arrows. So in this case, it was my life in a Brazilian Shakespeare Festival. And that's like my holy grail of stuff I want to find. I want to find the Brazilian version of Oh, and he just made the two pups. Oh, I was watching the two pups and two pups was brilliant. I loved that movie. And I was like, Man, this guy made its own version of slings and arrows. That's what I really want to. I don't know if anybody has even dubbed it and I do not speak Portuguese.

Alex Ferrari 24:10

Right. So how committed are you sir? Will you learn Portuguese just to watch?

Matt Bird 24:17

Well, that's what Pete Buddha judge did. Right? Pete Buddha judge taught himself Norwegian because the he was reading a book series that was translated from Norwegian. And then the final books were not translated from Norwegian. So he taught himself Norwegian just to read the book series.

Alex Ferrari 24:29

God bless him. God bless.

Matt Bird 24:34

See where he ends up?

Alex Ferrari 24:35

Yeah, exactly. So let me ask you a question. So yeah, I don't want you to give all your 13 laws away. I want to be somebody who can actually buy the book. But yes, what is your process for coming up for an intriguing concept for our story?

Matt Bird 24:52

Well, I think that, you know, I don't always agree with like, Senator, but I think Blake Snyder, you know, was right on the money when he talked about the importance of irony that You know, it's gonna be, you know, a schoolteacher cooks math, you know, not a drug lord cooks math, you know, not the son of a drug lord cooks math solver, Adobo cooks met Montessori, school teacher cooks MEB. That's the story. There's got to be an ironic element to it. I talked about on my blog, I've got a whole series of how to generate a story idea. And, you know, I talk about, for instance, there's all sorts of ways into it. Like one way, you know, one of the ways to generate your idea is, you've always thought she, the thing you've always wanted to do, but you know, you would never do so it can be the the science fiction version of that is Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Like, gee, I wouldn't you know, I've gone through a bad breakup, I would really love to, if I could just have a machine that would wipe out all memories of this relationship from my head, then that would make me happy. And anyway, would that make me happy, and then boom, that's the story. You're off to the races. That's a great story. But it can also be a way to get a non science fiction story. Like, you know, I've just gone through another bad breakup. Some stories begin with bad breakups. I've just been through a bad breakup. And what if I tracked down every girl who's ever come to me, since elementary school, and tracked debt and made a list of the top five girls who've ever done and track them down one by one and interview them about why they dominate? Well, again, that's something that Nick Hornby did not do. I promise you he did not do that. I promise you that no one has ever actually done that. But it's something we've all thought about doing. Like oh, wouldn't that be, and boom, that's a story that got turned into the novel, high fidelity, and then the movie high fidelity, and then the TV series, high fidelity. And that's, you know, that's essentially he's doing the same thing, that Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind had going, like, you know, what's, what's an idea I had, of course, I feel like, the best way to probably create a story these days, if you want to create something big, if you want to create a big sale, I talked about the Hunger Games, how she was reading about the legend of PCs, and all of it, all of the Hunger Games in the legend, PCs, so that they were like, you know, oh, we've got an empire, we're rolling over all these kingdoms. Once a year, we're going to have all the kingdoms and, you know, they're beautiful young people too. And then we're going to put them in this labyrinth, and we're going to force them to compete. And this will be a way to, you know, to show them that we have conquered them. And that, you know, we could kill them on a times, but instead, we'll just kill their two most beautiful kids, and force them to fight to the death just to show our power. And she was like, well, she could have done three things. She could have said, Okay, well, let me just, you know, this is IP, a PCS is IP, why don't I just go back? And it's, it's the best kind of IP, it's IP that's in the public domain. I just read a book about Theseus, but then she was like, but you know, then first of all, you shouldn't really own it, because anyone can write a book about PCs. So she's like, well, what's a version of PCs I can own? And I could sell it in modern day, but that would be kind of a stretch. She's like,

Alex Ferrari 27:54

you know what, you know what? We're not too far away. I would have said that. Yes, you borrow it. I would have said I would have said that a few years ago. But now what what you thought was impossible is not possible, sir. So don't don't authority.

Matt Bird 28:06

But then she was like, why don't I make this the post apocalyptic version? And all she did was take an existing story. All she did was take existing IP. And she was able to make that into a billion dollar franchise herself. I don't know. Does Susan Collins have a billion dollars? She spent a billion dollars find out right?

Alex Ferrari 28:29

Between a couple of them shirts. I think she's she's done. Okay. So basically, she just took she just basically took Hamlet, let's say, and made it into a long sea or something that's completely in the public domain. And just made an entire IP out of it.

Matt Bird 28:42

Yeah, she she took she took free IP is what Disney spamming him with. That's my endgame. Yeah, with Disney has been doing for a long time is taking free IP and, and turning it into something they can been owned and try to, you know, force everybody else to, you know, try to, they like to pluck things out of the public domain and then suddenly claim to own them, which is a neat trick. But she that's what she did. She she took something in the public domain, plucked it out, made it hers and made a fortune. You know, I talked about but I talk about other things that aren't necessarily sci fi related. I talk about the importance of a unique relationship. I talked about how, you know, you kind of bully and a boy, a boy who's being bullied. Well, that is a story we've seen a million times, but then the bully hires, but then the boy hires the meanest body to protect him from the other bullies. Then that's the movie my bodyguard. That is a unique relationship. We've never thought

Alex Ferrari 29:38

I love that movie. I love that movie. So I can't believe you refer to that. That's it was released in 1980. I remember watching it as a kid, and I thought it was the most awesome frickin movie with Matt Dillon. Is it Matt Dillon? Adam Baldwin, yeah, Adam Baldwin and Matt Dillon with the two picks. They weren't big Stars then but those are the stars. Oh god, I can't believe you made a reference to that movie. It's like one of my favorite movies of all time. I love that movie.

Matt Bird 30:05

But that's, you know, we've seen both those characters many times. These aren't unique characters, but it's a unique relationship we've never seen you know, the week kid hired the bullied to be as bodyguard before, or you know, work at another high school movie like election, you know, about a war between a girl running for student body president and her civics teacher. And it's like, okay, we, you know, we've seen characters like this before, but man, that's a unique relationship. We have never seen that relationship before. Or, you know, I talked about paper, Moon, you know, a con man and his 11 year old accomplice who may or may not be his daughter. And it's like, okay, this is if you can, you know, you don't have to be science fiction, obviously, one of my ideas, you know, it's like, okay, I mean, these days, gentlemen, people talk about high concept. They talk about science fiction, they're talking about like, okay, you know, here's a high concept idea. It's, you know, we've got it's 1000 years into the future. And it's like, well, what's up there? You can, you know, the simplest high concept idea out there the simplest type concept. You know, the, if a pure high concept is something where you put together two words, and you sell it for a million dollars, and to me, the ultimate example of that is Wedding Crashers. Two words. Wedding Crashers, boom, done sale. Make a movie. It's a funny idea. It makes you laugh, like, oh, people are graduating and you're like, oh, you know, you just you're instantly like, I can't wait to meet these guys. I can't wait to meet these guys who crush other people's weddings. Or what if not big budget. Easy and easiest thing in the world to make?

Alex Ferrari 31:35

Yes. Like what if? What if dinosaurs came back? We can bring the answers back. That's done. Yeah. And we opened the park but

Matt Bird 31:44

it's so funny that they've never really there's never really been a dinosaurs rampaging through Manhattan movie. Isn't that strange?

Alex Ferrari 31:53

I mean, last world. They did do not in Manhattan, but they did he they did come towards

Matt Bird 31:57

Spielberg. Spielberg loves the suburbs. So you know, Spielberg is like if I'm gonna have a T Rex going through America, I'm gonna put them out in the suburbs, but it's really weird. I was working in idea for a while I never kind of done you know, obviously, that may be one reason why it's harder right than you think. But you know, it always struck me in the Thor movies. We've never really had a like frost giants attack downtown Manhattan moment.

Alex Ferrari 32:24

But you know, a lot of things if attacks Manhattan over the years, I mean, we were we're good if it's between a giant Stay Puft Marshmallow Man Godzilla. I mean, Manhattan's had its day don't get there's no lack of things attacking Manhattan over the course of movie history. I think we're okay. But yes, I've never personally seen a dinosaurs I think shark NATO I'd never seen any the movies. I'm assuming there must have been a shark NATO in Manhattan at one point or, like, that's a perfect thing. Shark NATO that sold. So, I love this. There's one little meme that's on around going on social media is like remember when you think you had a bad idea? Remember that one day once there was a guy in a room who said let's put sharks in tornadoes? You know, I mean,

Matt Bird 33:15

that's, that's and then and then seven movies later how many of those movies that they made my

Alex Ferrari 33:19

god so much money they've made? It's ridiculous. So then how do you so we would talk a little bit about characters with like Indiana Jones and, and Walter White, let's say how do you write that enduring character? That character that that just sticks with you like like an indie like, I mean, we can we can analyze indie we can and a lot analyze Han Solo if there's two to Harrison Ford characters

Matt Bird 33:46

to George Lucas, there's unfortunately no

Alex Ferrari 33:48

Yeah, or, or any of these characters that you just like, oh, like forever I will be with this character, James Bond is another one of those characters that endures, regardless of how he's transformed, transformed over the course of his journey in history of filmmaking. So what do you how do you do it? How do you write an enduring character?

Matt Bird 34:09

Well, when I talk about in the, I think the title of my next book, depending on how the publisher actually feels, but will be believed care, invest. And I talked about how like, you know, again, you've got they're going to give you five pages, maybe 10 pages when they read it, and what they're gonna want to do it and those five pages are going to want to believe, care and invest. And they're going to want to say, You know what, I was just talking on the next episode of my podcast about this. How, you know, Ray in Star Wars ray in The Force Awakens is a classic example of like, right away, we're seeing her and her wife is so strange. If it's so filled with like, she makes that bread, that spherical machine she's got wherever that was awesome. Yeah, that causes you to totally believe in this world because you're like, Okay, that's so weird. You couldn't make it up. You know, like, Okay, this must be real. This must be a real world like so any thought I had going on? have like, Okay, this is all going to be wise this is going to be fake button pushing manipulating character, like, okay, no, this, this feels real. And then they get you to care because the characters suffering the characters being embarrassed. You know, in this case, she's living hand to mouth, she's living this very hardscrabble life and then they get you to invest because she's taking care of herself and she is taking care of herself wonderfully. First they show you that she is doing all she can to make all this money, she's doing all she can, could work very hard. And you know, is like doing going to, you know, we see a rappelling down into a destroyed Star Destroyer, we see Oh, see, you're going to do current length, and then you get the point 10 minutes and where we've already seen her desperately trying to get money from the pawnbroker or from the scrap dealer, and she'll do anything to get this money. And then she gets destroyed. And the droid says, And finally, the scrap dealer who she's always been trying to make this money off of. So that'll pay a fortune for I'll pay a fortune for eBay. And she says, and then suddenly, she says, I'm not selling, I'm not gonna set one. And oh, my God, we love this character five now, because we've seen that she's, we believe in her, we care about her, we've invested in her, and we desperately want her to make that money. We at this point, we want her to make that money, we want her to be successful. And then she gets a higher calling. She says, No, this is about more than me, this is about bigger than me. This is about BPA, I am going to not sell him. And like what better example this could be where we talk about, you know, The Hunger Games, Why can the Hunger Games, you know, we talked about save the cat. And, oh, it's so important. It's so important. You kind of have your character save the cat right away. And it almost, it's almost always a mistake to have your character save a cat. Because we don't identify that we, I've never saved a cat, you have never saved a cat. It is a very rare thing to actually save a cat. That's not the sort of thing we see. And it's like, oh, that's just like me, I save cats all the time. What is what is the first page of The Hunger Games, I think the second paragraph of the Hunger Games, she wakes up in the morning, and she sees the family cat. And she thinks, you know, I really want to kill that cat. I almost killed that cat before I tried to kill that cat before I didn't succeed. I really want to kill the family cat today. And then she decides not to kill it. So she sort of saves the cat, right? Because she almost kills it and then decides not to kill it. So that's one version of saving a cat. But then she leaves the house and she kills a different cat. Within five pages later, she sees a noble mountain lion and she concerns landing. And it's like, no, I'm gonna kill it and cook it. And she does. So it's like, this is the ultimate opposite of Save the cat. This is like literally she almost kills the family cat and then does kill another cat. But we believe we care. We invest we believe in her life because it's filled with, you know, even just her story of almost going to family cat. It's like, oh, that doesn't sound fake. Because that sounds like because no one would make that up to manipulate me because that makes me not like her like, Okay, this must be real. And then we care so much because oh my god, she's poor enough where, you know, she would even consider that. And then we've asked because what's the next thing she does, she goes up, there's an electric fence, I'm gonna slip through the electric fence. I'm gonna take out my bow and arrow, and then I'm gonna go hunt. And oh my god, like we love her. But then so we believe in her. We cared about her, we invest in her. And then what happens on page 10, or page ad or no 25 or so is she is so good at looking out for number one and taking care of number one and making sure that she survives, she'll do anything to survive. And then she volunteers for The Hunger Games to save her sister. And she rises up above it. So we totally believe in her world. And then she rises up above it. And oh my god, we absolutely love her now. And now you're in. Now you're in

you know, it's James Bond is the perpetual exception. I just rewatched I was all prepared. The new James Bond movie was supposed to come out. And I watched all 25 James Bond movies. Wow. And then I was all set up. I was timing it exactly. To the moment the movie came out. And then the movie was cancelled. But James Bond is the perpetual exception. You know, certainly before Daniel credit comes in, he never changes. He never learns he never grows. He doesn't. He doesn't really get humiliated. He does though. Like that's such a key Amen is your hero getting humiliated? And there are key moments, you know, if you look at Gold finger, you know, he's, he's, you know, could not be more suave. And when he blows up the tanker, and then you know, takes off his wetsuit and he's got on a tux underneath and then But then he goes to the woman's house to have sex with her. And then it's it's the most ludicrous thing that he sees in reflected in the iris of her eyes. Someone coming up to kill him. And then that's a little bit of a moment of humiliation. You get just enough in the Bond movies. Okay, I I definitely you mentioned some he's getting a little bit of humiliation here. And then of course, he turns the girls so that she gets knocked on the head instead of himself, because he's despicable. Don't get me wrong. He has a despicable human being. And but he's the exception. You know, certainly you look at Indy, you look at Indiana Jones and, you know, instantly right away he misjudges the whole bag Same situation, he gets betrayed by his assistant, Alfred Molina, he then has to run through the forest. And then he gets forced on his knees to hand over the idol to duck and then add on of course, he's also he's free to snake. He hate snakes, and he gets away and there is a snake in there. So this guy who was seemingly not afraid of anything, is somebody terrified of snakes. And, you know, he can do it. He's got the skills, he does amazing work, and yet he horses and he gets humiliated. And yet he gets knocked down in a way that speaks not just to his interpersonal failings, but to his inner his intrapersonal failings into what is really wrong with his character. What is his deep personal flaw? It all speaks to it. We love him. We love him so much. That's what it's all about is you know, you you believe care, invest. And then, you know, and then suddenly, there's a moment where it kicks in. Suddenly, there's a moment where you're like, wow, okay, now I'm really on board with this person.

Alex Ferrari 41:00

Well, you look at you look to characters like the like bond pre Daniel Craig, because I think I think still Casino Royale is the best Bond movie ever. In my opinion. There's just it's, it's It's a masterpiece of the whole canon of James Bond. But you look at characters like bond or Sherlock Holmes. And they're both basically superheroes in many ways. They are godlike, and they generally didn't change. Like, you know, Sherlock generally never changed that people that change the people around him, like, Watson is kind of like the person who's learning the lessons along the way. And we kind of identify with Watson, in that sense, but Sherlock never sure looks the same violin playing dude, from the beginning to the end. And same thing with the older bonds. So there are those kind of and that's why I think it was so difficult to make a good Superman movie, other than the original Donner movies, because you can't write for a guide. It's hard. It's hard. That's why the mountain lip is all of them were human. Basically, all of them were even though there were gods, they all had the same failings of humanity. So

Matt Bird 42:11

what's interesting, both Sherlock Holmes and James Bond are addicts, you know, like James Bond, they talked about in the original movies, they talk about, you know, like, oh, you know, you've got liver problems, right, from right from the opening movies. And, you know, they talk about, you know, people always act like, oh, you know, the Bond movies were set back in a time when it was great to be, you know, this swaggering dude who had all these things. It's like, he gets criticized right away, you know, like, he was seen as sort of a monster like, Sean Connery was perceived by the people around him in those early movies, as being this sort of Monster is dude, and who had serious flaws who had serious problems. Yeah. And you know, we go today like, oh, he was a womanizer. And he was he drank too much and he smoked too much and Oh, of course back then when they made movies they didn't even realize that was problem like no they did they realize that was from and of course Sherlock Holmes was addicted to opium he would inject himself I mean, I opium he would cocaine, you wouldn't have to myself with liquid cocaine, and, you know, with a very troubled person, and in the in the stories, and I think that we tend to, we tend to women, we tend to think like, oh, they're the past, where heroes were allowed to be perfect. But as he said, even with the gods, the cons were, you know, in the Greek gods, the gods were very flawed. I mean, I think the oldest piece of literature that is still with us is Gilgamesh and Gilgamesh you know, could not you, you I dare you to find a screenwriting gurus book where anything in it does not apply to Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh could not be a more perfectly fine hero, his journey cannot fit modern story structures better. So you've read Gilgamesh, and you're like, wow, nothing has changed, like nothing has changed. And the reason why nothing has changed is because good storytelling it rise is based on human nature is based on what is the fundamental truth about what it's like to be a human because that's what stories are about stories are about what is the fundamental truth about what does it mean to be a human in this world? And even if you go back to ancient Mesopotamia, even if you go back to the, you know, 3500 years BCE, it's human nature was the same. And you read Gilgamesh, and you're like, Oh, my God, it's, it's, I it may be my favorite book. And it's the oldest book we've had.

Alex Ferrari 44:23

Yeah, and it's just you know, it's, it's, it's similar to what we're dealing with today is the human condition just with less iPhones. Essentially, exactly. Now, structure is something that is talked at nauseum about in storytelling, and specifically in screenwriting, is like you need to follow this formula, the hero's journey, the three act structure, at page this you have to have that happen a page that that happens. What is your take on story structure in general?

Matt Bird 44:56

Well, you know, at first I was like, oh, all this The writing gurus have taken that have covered that it's fine. Everybody has their structure, I don't need my own structure. And then of course, inevitably, you start giving writing advice. And everybody, you always end up with your own structure. And every, you know, I sort of ended up with sort of 14 points where I started out, what I realized about structure is that, you know, you have people you have people like Robert McKee, who are saying, well, you know, I, here's pharmakeia, you were on a cruise, you have paid for the Robert McKee cruise, and I'm going to tell you what all good stories are like, and then somebody stands up in the back and they go, my stories don't like that. And then Robert McKee can tell them, Okay, leave the boat swim home. My, my, my structure doesn't apply to you, he has to claim that all structures apply to him. So he talks about like the micro pod and the mini pot, and things like that. And that's what gurus tend to do is they drive themselves crazy trying to cover all the exceptions, I realized right away, I'm not going to try to cover all the exceptions, my structure only applies to stories about the solving of a large problem.

Alex Ferrari 46:08

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Matt Bird 46:18

So, I mean, the biggest problem you can have when you're trying to structure is like, okay, all good movies are like this. And then someone says, Pulp Fiction. And you're like, exactly, both fiction does not have a modern structure. And Polk fiction does not have a structure that matches the structure of any other movie. And because Pulp Fiction is not about the solving of a large problem, it is an ensemble film, it is about several different stories, it is they overlap, the time is crazy, but if you're going to write, but I'm like, Okay, you be you, you go off and be Pulp Fiction, you're brilliant, don't change, never change. But most stories are about an invoke an individual solving a large problem, my structure only applies to those stories, not gonna apply those others. And then I realized what story structure really is, is it is not a set of rules for that Aristotle, or Mickey, or that anybody else has said, I'm going to dictate to you what the rules of story should be. It is merely an attempt to list the steps and missteps that people go through when solving a large problem in real life. So in human nature, we tend to go through a series of steps and miss steps on the way to solving a large problem. And when you see a story, and when somebody says, Oh, the structure is not good on your story. They're not saying, oh, you know, you didn't read Blake Snyder and hit all his beats. What they're saying is that this story does not ring true to me, this story does not ring true to human nature. To me, this does not feel like an identify for believable journey from becoming aware of a problem to solving that problem. Or to succumbing to the problem if the movie ends tragically. And that's what they really mean. So you can't just go like, well, I don't believe in your stupid structures guy, I don't, you know, I'm

Alex Ferrari 48:10

an artist. I'm an artist,

Matt Bird 48:12

I'm an artist, I don't do paint by numbers, man, then you're like, Okay, that's fine. That's great. You're an artist. And that's wonderful. But your story is not ringing true. And if you want to say, okay, you know, if you're writing, there will be blood or something, if you're writing something where it's like, okay, this is about a strange person who is not interested in being your hero, who is not interested in doing that, that's fine. You know, if this is not something where it's like, I'm going to invest in this person, I hope this person solves all their problems, then that's fine. But if you are, and you probably are, then you will need to follow the steps and missteps that most people will tend to follow in real life when solving large problems. And that was how I generate my structure now. It's funny. So 13 of my 14 main steps in my structure, applied event, there's one that doesn't, and it's the one that was it's necessary to solve a paradox of storytelling. And that paradox is the break into act three, I don't refer to x one, two and three, I talk about the four corners of your story, but the move from the third quarter your story to the fourth quarter your story, or as it's usually referred to by screenwriters, the break from act two and act three, then we all know that the hero is supposed to be proactive at that point, right? supposed to have a proactive hero, the hero has realized what his problem is realized what the problem in his world is. He's confronted his flaw, and now he's ready to take on the world. He's ready to bring the fight to the bad guy. But do we actually want in the final quarter of the story? Do we actually want the hero to just show up to the bad guy's house and beat him up? No, we don't want that. So this is a paradox. Like if we want the hero to take the fight to the if we want the hero to have changed enough as a person and to have gone through the personal transformation necessary to now say I'm ready to show up at the heroes house and beat him up. But then we don't actually want to see that happen. So what happens? Why, why is the hero giving the writer conflict? Why is the audience giving the writer conflicting signals here. And of course, it all comes down to Star Wars, and even my mind in the original kind of Star Wars, that's exactly what happened at the end is they're like, we have the plants of the Death Star. And we're gonna just show up at the heroes front door and beat a pup, we're gonna find the Death Star, wherever it is, in the middle of the galaxy. We're gonna fly there, we're gonna shoot, we're gonna shoot it the fawn the Death Star, and we're gonna blow it up. And nobody likes the movie. George Lucas was showing this movie to people and they were ashamed. They were like, Oh, George, I'm so sorry. Well, you know, maybe the next one will work out for you. You know, this one's just, it's not working. And George did the number one thing that everybody should do, he went back to his wife. And he said, Honey, why isn't this working? And she said, Let me fix it for you. And she said, Well, duh, your problem is, it's good that your heroes now have the information they need. They've got what they need to defeat the bad guys. But then the bad guys show up on their doorstep. And she just we ended the movie and redubbed the movie, and shot new insert shots to create an entire storyline that was not there in the original film of, okay, yes, we know, have the plans with the desktop, but then the desktop shows up to blow us up before we can go there to blow them up. And they are about to blow us up. And, you know, you look at this in suddenly, once you see this, you see it everywhere. So that is you see it everywhere. That, oh, you know, I have personally transformed it become a productive person. But then the timeline gets unexpectedly moved up. And suddenly they're here. So it's the one step in my structure where it's like, Okay, that one is there to address the paradox that is, you know, because in, but it doesn't happen in real life anyway. Yeah.

Does, it doesn't happen that time, like, does tend to get moved up. But it doesn't. But that's not necessarily something that's based on real life, it's not that the timeline always gets moved and always gets moved up in real life, although that does tend to happen. You know, I talk about my structure, how, you know, I would, I would sit there and I'd be like, Okay, I need to master this structure. And I need to do this, you know, this writing job that I've just gotten. And I would go like, okay, so I think I've messaged the structure, I'm gonna do the writing job. Okay, first thing I'm gonna do, when I do the right job is I'm gonna, I'm gonna sell them a pitch, they're gonna like the pitch, you know, for how I'm gonna adapt their novel. And then I'm gonna come up with my beat sheet, I've got the beat sheet, and I'm going to pitch it to them. And they like the beat sheet, they go, that's good. Write it exactly the way it is on your beat sheet, and you'll make a million bucks, we'll make a million bucks, we're all gonna get rich. And then you sit down, and you're like, and they tell you, Okay, you have to determine the screenplay in six weeks. And you're like, This is fine. That means I just have to write like three pages a day, it's gonna be beautiful. And then you're writing your pages every day, you're writing your scenes. And then you get halfway through, and you realize this beat sheet that I sold them that they love, it sucks. Like it is, you know, I have my plans have unraveled. And I now realized that this beautiful plan I have, I have to throw out the window. And I have to start over even though I this is what they told me to do. Even though this is the approved plan, I have to repeat this thing. against the rules, an outward repeat that I have to do in order to actually write something that's going to be good. And then I'm gonna have to sell this to them that sell them the thing they don't want. And it's going to work and I realize like, Okay, this is what happens when I would get hired to write screenplays. And it's also what happens in screenplays because this is proof of what I was saying that the story structure is the structure of how you solve problems in real life. The when you're writing your story structure and you're creating a btw story structure, you will end up following the same storyline where you will end up having to in any good movie, they throw out the map halfway through, they get to the halfway point and they're like, Okay, crumple up these plans, throw them out. We're proactive now we're improving. We're having to solve this problem from scratch. And this exact same thing will happen to you Ironically, when you're trying to write it, you will get halfway through and you're crumple up your beachy, throw it out. You're like oh my God, I am winging it from now on. I'm running. Gotcha. And if you don't do that, it's gonna be terrible. If you just write the exact pitch that you sold them Yeah, it's gonna be terrible.

Alex Ferrari 54:41

Now one one thing I wanted to ask you is something that I guess does not get talked about very much in in screenwriting in general and I'd love to hear your take on it tone. Can you discuss tone because tone is so so important. You know if it It's just so important, especially to all the great movies have good tone, or have appropriate tone.

Matt Bird 55:07

And if and if you can master tone, then you're set. Because if you can, you know, tone is about setting expectation. And if you can set the audience's expectations, if you can tell them like, Okay, here's what to expect from me, here's what I think you should expect, here's what I think you should want, then, and then they want it and then you give it to them, then they will have no idea that you are a master manipulator, who has tricked them into liking this story that they would not actually have liked, that they would have had, you know, I always say the ultimate example of challenge is go back, I'm going to re edit Star Wars, and I'm just going to change one thing, I'm going to take off the opening frames of the movie. And so now instead of saying, Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far away, no, I'm sorry, what does it say

Alex Ferrari 55:54

a long time, a long time ago, in a galaxy far,

Matt Bird 55:56

far away, a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away. And I'm going to take that title card off the front of the movie, and instead, I'm going to put a title card that says it is the year 25,193. And then boom, and then you have the whole rest of the movie, the movie would suck. That would suck if Star Wars was not set a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, but it was set in the year 25,193, then we would go okay, so this is a science fiction movie. And this is going to follow the rules of a science fiction movie. So they are going to we're going to be dealing with explosive decompression every time that an airlock is opened, we're going to be dealing with supercomputers that have been programmed to take over the world.

Alex Ferrari 56:41

No sound, no sound, no sound in space. No sound

Matt Bird 56:44

in space, of course, no sound in space. Close. And then you're going to be watching this movie. And you're going like this is not the or 25,000. We've got wizards. We've got princesses. We've got you know, we've got storming the castle, we've got all these things. And this is a fairy tale. This is a story that should be said a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. And you you have not delivered the story that you promised to deliver. And that is tone. You know, I think that 90 If you're not a screenwriter and you're watching that movie, you're like, oh, that's sort of funny that it says it said a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. And you won't realize what that is doing for you that that is solving the movies problems by establishing that tone. That that is saying like, nope, not, it's not what you think it is. It's something else. It's my thing. Let me tell you what my thing is going to be. And I talked about, you know, I when I break up tone I talked about with tone, you know? So the first part tone is genre, establishing your genre establishing your sub genre, that was what that's title card was all about establishing like, no, no, no, no, no, this isn't what you're expecting sci fi. This is a sub genre. I talked about how satisfying genre expectations how you've got to satisfy some genre expectations, but not a lot of genre crustaceans. I talk a lot about on my blog about Game of Thrones, and about Game of Thrones, you know, they satisfy just enough genre expectations. And then they just didn't satisfy so many of them. First of all, they kept killing off the hero. They're like, Oh, by the way, Ned Stark's the hero. No, no, wait, he's dead. Okay, now Rob serves the hero. No, no, no way. He's dead. So that was all about upsetting expectations. But man, if you love fantasy, you still love that series. And it's, it's if you don't want to fail, I mean that that's the dream is Game of Thrones. Because if you love fantasy, you'll love that series. And if you don't want fantasy, you'll love that series. And that if you can satisfy the fans of the genre enough so that they're the ones who want that book for the first 10 years of Game of Thrones existing only Fantasy fans, only Fantasy fans barn and read it. And I don't know if you knew any of these people, but these people kept going to people who work fancy fans going like, Oh my God, you have to read these books. They're amazing. And the manager like Gone, forget it. I'm not gonna read these big, thick fantasy books. Like I am a serious human being I am an adult. I do not read big, thick fancy books, and all the fantasy fans that was driving them crazy, cuz they're like, No, you will love it. It is literature. It is great. It is entertainment and literature and everything. And so that is such a big part of it. I talked about framing I talked about obviously, the dramatic question is something that screenwriting people talk about a lot. How, you know, establishing what Frank question is establishing what the what, what you're going to address at the end and what you're not going to dress and when it's going to be over and when it's not going to be over. You know, Star Wars is not about toppling the Empire. And if you get to the end of Star Wars, and you're like, what the Empire still standing, you know, this movie sucked. That would be that would be bad. They have to you know, they establish the drain question right away and always go like We have to get we have to get these plans to the rebels in order to because we have a plan for how to blow up the destiny. We got to plan for birth or we have to get it to the rebels. And then we're going to bought the Deathstar. And that's what this movie is about. And yes, you know, they don't even kill off Darth Vader. They leave it on unclear about whether he's dead, but they don't even clear up Darth Vader, and they don't. They certainly don't, you know, conquer the galaxy. And they have to establish their dramatic question right away. I talked about framing sequences I talked about parallel characters are great if you every time your character meets. And you know, your character should be constantly meeting characters that are like, Oh, I could end up like that. I could. This is the extreme version of what I'm thinking about being like, Oh, my God, this this person I'm on the verge of becoming, do I really want to become like that, look, this other character? Or if I don't do it, look at this other character who ended up dead. And that is a great way of establishing expectations. If you establish like, Oh my God, look at all these people. I could be this person. I want to be this person. I don't want to be this person who, you know, who tragically ended up dead because they didn't do the right thing. Or because they didn't do the right thing. What am I going to be? What is that?

Alex Ferrari 1:01:12

So it's like, are you going to be Darth Vader? Are you going to be Obi Wan? If you're Luke? That's the That's the question. Because you can go either way

Matt Bird 1:01:19

towards you're gonna be hot. Are you gonna? Or you're gonna reject the force? Yeah, does

Alex Ferrari 1:01:24

exactly. So there's, there's that as opposed to the the prequels, you know, which have their place. But anagen had the choice of becoming Yoda. Or, or, or becoming who he or becoming the Emperor, essentially. And he chose poorly. If I may use Indiana Jones. He chose poorly.

Matt Bird 1:01:49

But we can see now

Alex Ferrari 1:01:51

there's a whole there's a whole episode that you and I could sit down and just deconstruct the the prequels

Matt Bird 1:01:59

for the rest of this because nobody's done that.

Alex Ferrari 1:02:04

I'm sure no one. No, no, Georgia. People, I think, I think genius character. What are you talking about? Oh, I'm sorry. But this was awkward. Like, you know what, but with all that said, when you saw the trailer for Phantom Menace, oh, my God. Don't tell me you didn't.

Matt Bird 1:02:23

I worked in a movie theater. I and we could watch it over and over. And we did it. Trust

Alex Ferrari 1:02:28

me. i We all drank that Kool Aid. And when we walked in, I promise you when you walked out a Phantom Menace? Because you're you're of the similar generation as I was. You're close to my vintage, sir. You walked out a fan of minutes and said, Oh my god. That was amazing. The pod right? I mean, I did. I did.

Unknown Speaker 1:02:50

And then I did not. You did not. You did not like it. You did like it like I did not like

Alex Ferrari 1:02:55

so you didn't talk. I drank full kool aid on that one. But then I watched it. I watched it with my daughter a year or two ago. Just to introduce her. She's like, well, let me see that. You know, Anna, and I'm like, All right. Well, Jana, so we watched Phantom Menace, and I could barely watch it. It was so bad. It was so so I mean, great action sequences, great lightsaber battle, great pod raise. That was fun. But it was mind numbing. He was he was really bad.

Matt Bird 1:03:31

But anyway, really bad.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:32

I like I said, Well, like you said earlier. It's like you said earlier, we're not the first to discuss the prequels on the internet. Now, before we go, I'm gonna ask you a few questions to ask all of my guests. What are three screenplays that every screenwriter should read?

Matt Bird 1:03:46

Oh, man, see, I listened to some of your old episodes. And I remember hearing us at and I thought, oh, okay, I shouldn't I shouldn't make sure that I that I answered it. And I don't, you know, a really underrated screenplay. When I was in film school. At one point they were throwing out a bunch of old issues of screenplay magazine. And that would always print for screenplays in the back. And I grabbed one I'm like, hey, that's good screenplay. I'll pick it up and read it. And I thought just on the page, one of my all time favorite screenplays is Donnie Brasco by Paul snazzy. Oh, no, it's great. It's great. Great movie and just brilliantly written on the page. And there's never been a better monologue in film history than the forget about it. monologue where they're talking about all the different all the different meanings of the phrase forget about it. I think that that is an absolutely brilliant screenplay. You know, if you're talking about my all time favorite movie, you know, that's Harold and Maude. And I feel like that is a perfect screenplay as well. And an absolutely absolutely brilliant absolutely heartbreaking. You know, there is no better ending, I think in film than the ending in that film. Um, let's see what I would say hard to choose. It's so hard to choose.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:01

I mean Spaceballs. Spaceballs obviously. Well,

Matt Bird 1:05:04

obviously, oh my god. On my own podcast, I just found out that my my, my co host has never seen Blazing Saddles. Oh, oh, it's just assumed it's bad and it's never seen it. So I'm gonna say so in honor of him. I'm gonna say Blazing Saddles for the third month, although, of course, let me tell you all right now, don't write Blazing Saddles. Today. You were never there amount of trouble or trying to do that.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:29

I when I saw I saw Blazing Saddles. When I was in the video working at the video store in high school, I saw Blazing Saddles. And at that point, I said, in the late 80s, early 90s, like, how did this movie get made? Like, even then, I was like, it was not nearly as taboo as it is today. And you watch it, and you just like, I can't believe you got away with it. And I'm like, they'll never be another movie to do something like this. And then bore out came out. I was like, okay. All right. That was and that was the last one and nothing like Bora has has has ever come back on screen since that. But those two specifically, they just pushed that envelope. So good, good. Good choices, good choices. Now, what advice would you give a screenwriter wanting to break into the business today?

Matt Bird 1:06:14

Well, hear is, you know, let me can I just, you know, I was thinking like, Oh, he's gonna ask me about business stuff. And that's not really my, my brand. But that's like you I do, because it's not my brand. I do have say about business that I haven't said a million times before and a million other podcast. Can I talk about the number one thing I wish that I had heard before, I had my heat and I was selling? Yeah, and that is what happens in a meeting. Okay? If you're on the counter and water tour, if you're going around, it's good. Bottles, couches, you're getting them you're getting the water. Here are the things I understand. The first thing I didn't understand is that this meeting is a consolation prize. You are getting this meeting because your manager agent sent you sent them your screenplay. They loved it. But they decided not to buy it. And they said, as a consolation prize, we're gonna meet with the guy. So if they had watched your screenplay, I always thought in like, oh, they asked me what you mean. That means like, what my screenplay, that means they're gonna buy it. And I would go in like, oh, I would go in there like, hey, you know, we're here to talk about how you're buying my screenplay. I would have this heartbreak every time of like, you're not even Why are you meeting with me if you're not even gonna buy it, because this is a consolation prize. So that's the first thing and is that they've read it. They loved it, but they decided not to buy it, they asked to meet with you instead. And then as a result, there's three phases to a meeting. And this took me forever to learn. And that's the first faces you talked about the thing that they read appears and they loved and they decided not to buy, and you maybe can talk them into buying in any way. But you've got to be very clear that that's not what you're doing. Like you understand that they loved it, that they're not going to buy it, and that you're not doing but you know, you're suddenly going like, maybe you should have bought it, maybe it shouldn't be your manager. So that's phase one. So there's three phases of beating. Phase one is talk about the thing that they read of yours that they liked, and maybe try to convince them by afterall. Phase two is open assignments. Hopefully, your HR manager has asked them in advance. What open assignments does this production company have? That that they are looking to hire writers for? What novels have the option that then they couldn't get anybody to crack? What what you know, idea, crazy ideas this producer have that he's trying to hire some screenwriter to do that. You want to find out what are your open assignments and you want to pitch them on what the open assignments are. Hopefully you found that advance with the open seminar and you prepare to pitch in advance. And then step three, is you're going to pitch them on your new one. And you're going to pitch them like then they're going to ask so what are you working on? And you're going to say Oh, I'm working on you know, it's about a cow who goes back to ancient France, you're working on whatever you're working on and you're gonna pitch them but that's the least likely thing that's going to come out of it is they're just going to buy a wild pitch from you. And because here is the number one thing I learned from selling and more importantly from not selling, and I have never gotten into reading a bunch of sales books and I'm sure there are sales books out there that say this but I've never encountered one. And to me, this is the number one lesson of sales. And then is that do not sell them what you came to Sell. Sell them with they came to buy. Oh when you were meeting with that's good when you were meeting with a buyer. They the only reason anybody ever meets with a salesman and that's what you are. You're a salesman. The only reason why anybody ever meets with a salesman is if they have to buy is if they are in trouble and they are out of product and they need new product and they're going to get fired if they don't buy new products. That's their whole job is to gather up new product and they're out of product. They're running out there in a panic they need to buy but they're not going to buy what you came to sell. They're going to buy what they came to buy, and they know that dynamic you don't you If you're just a young screenwriter, you don't know that yet. But once you have figured that out, then the game begins, you're playing a game, you're playing cat and mouse, where you are trying to trick them into telling you what they came to buy. And they are trying to hold their cards close to the vest. And they're, they want to hear your pitch and see if it's what they came to buy, they don't want to accidentally reveal to you the secret of what they have come to buy, because then you will pounce and pitch that to them. And this is true of if you're writing, you know, if you're writing specs, this is true. If you're writing, this is true, if you are doing adaptations, if you're pitching your take on a novel so that you can get hired to do the adaptation. Here's the biggest occasion I ever get hired to write, here's how I get cuz I'd worn this at this point. And I said, Oh, you know, this is an amazing novel. And it's going to be so tricky to adapt, because you can either go this way with it, or you could go this way with it. And then I shut up. And I said, Oh, it's so tricky. You can go this way, or this way or that. silence, awkward silence. Awkward silence. And they're like, Yeah, well, obviously, yeah, you got to do a, and I'm like, exactly.