Ask anybody with a passing interest in movies who they think of when they hear the word “director”, and 9 times out of ten, you’ll get the same name: Steven Spielberg. The man is undoubtedly the most successful director of our time, perhaps of all time.

He single-handedly invented the blockbuster with 1975’s JAWS, but he’s also responsible for some of the most viscerally powerful “serious” films ever made: SCHINDLER’S LIST (1993) and SAVING PRIVATE RYAN (1998). He’s one of the biggest personalities in entertainment, recognized the world over with several entries in the top ten highest-grossing films of all time.

His brand has bled over into new media like videogames and television and his influence can be felt in the ambition of every single up-and-coming director. Simply put, Steven Spielberg IS movies.

There’s a growing pool of cinema enthusiasts who are quick to discredit Spielberg as a studio hack or a peddler of maudlin entertainment. I’ve certainly been guilty of downplaying his accomplishments on occasion, which is a hard feeling for me to grapple with since much of his work has directly inspired me to pursue film as my life’s work.

No matter your stance on the man, you have to respect his contribution to the art form, as it has indelibly shaped the very fabric of the entertainment industry. The earliest film I can remember seeing was a Spielberg film.

It was E.T: THE EXTRATERRESTIAL (1982). I could have only been three or four years old at the time, and I remember it well because it was during a tumultuous period in my brand-spanking-new life. My younger brother had just been born, and due to our growing family, my parents moved us out of the home in the working-class southeast Portland neighborhood in which I was born.

As my architect father was designing and building the house that I would eventually spend the bulk of my childhood in, we lived in a small apartment out in the suburbs, with a large, vacant field serving as a backyard. One day my mother sat me down in front of our TV and popped in a VHS cassette of E.T. THE EXTRATERRESTRIAL while she prepared dinner.

I don’t know why I connected with it at such an early age—perhaps the film’s suburban setting subconsciously connected with my own alienation that stemmed from my new, similarly-suburban surroundings. By the end of the film, I was a sobbing mess. Just soggy as all hell, blubbering as the credits rolled.

My mother leaned out from the kitchen to ask what was wrong. I remember my reply very distinctly, delivered between wet gasps of air as my little frame shook: “It’s just SO SAD!!!”.

Most people don’t really begin to start forming concrete memories until about four or five. And indeed, this early period of my life I can only remember in brief snippets, like a hazy half-forgotten dream (oddly enough, I can still remember some very vivid dreams from that time).

But there was something about this movie that just cut right to the core of my little heart, searing itself into my permanent memory before I could really begin to process what I was even watching. It’s a great illustration of cinema’s profound emotional power in the hands of a capable filmmaker.

Like laughter or music, cinema is a global language in its own right, transcending borders and cultures and connecting us all to the greater human experience. Spielberg is an aspirational figure for many wannabe filmmakers because he’s proof positive that anyone with talent and passion could go on to become the biggest filmmaker of all time.

Many of these filmmakers, myself included, will find parallels between Spielberg’s development and their own—to a point. In fact, the parallels stop right around the internship phase, unless you too got signed to a television-directing contract after showing your short film to an executive at Universal. My point is that Spielberg didn’t have the luxury of connections to get him in the door. What got him there was the singular desire and drive to make movies.

EARLY AMATEUR WORKS (1959-1967)

Spielberg was born in 1946, in Cincinnati, OH to a concert pianist mother and electrical engineer father. He moved around a lot as a kid, spending good chunks of his childhood in New Jersey and Scottsdale, Arizona. The Spielbergs came from an Orthodox Jewish heritage, which Spielberg would grapple and explore with in his films later in life.

As a child, he initially found himself embarrassed by, and at odds with, his family’s faith. As you can imagine, Orthodox Jews were probably rare in midcentury Arizona, so he was self-conscious about its strange perception to his WASP-y set of friends.

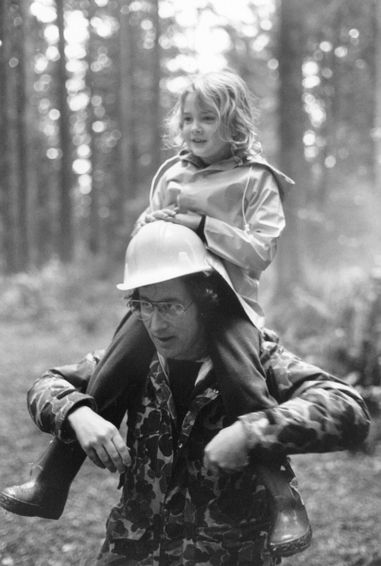

Despite his exotic heritage (to Arizonians, at least), Spielberg grew up like any other prototypical suburban American boy in the mid-twentieth century. He was quite active in the Boy Scouts, and as fate would have it, it was his stint in the Scouts that would lead to the making of his very first film.

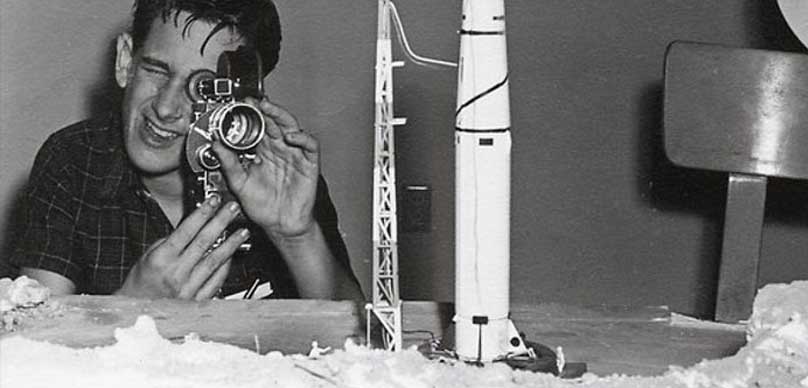

The twelve year-old Spielberg found himself with a photography merit badge to complete, but his father’s still camera was broken. Instead, he got permission to make a movie with his father’s working motion picture camera. He conceived and shot a short western, called THE LAST GUNFIGHT (1958). And just like that, Spielberg was bit by the bug. Hard.

I spent the majority of my childhood and teenage years making movies with my neighborhood friends, so it’s reassuring to see that Spielberg did the same thing when he was young. Even at such an early age, his aptitude for composition, pacing, and grandeur is immediately apparent.

It’s interesting that the subject matter of his early amateur work deals with the same themes as his professional oeuvre. Amongst his movies in this time period, he shows a preoccupation with alien encounters and World War 2, no doubt inspired by the stories his father would tell him after returning from the war.

He’d later realize a lot of these themes again on a professional level, such as CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND (1977) and SAVING PRIVATE RYAN. Looking at the whole of his filmography, one notes that a substantial percentage of his work takes place in the World War 2 era.

It’s clear that the conflict and the resulting cultural shifts profoundly shaped him, giving him an appreciation for history and dramatic stakes. His 1961 short, FIGHTER SQUAD, would be the first time Spielberg ever tackled the subject of World War 2.

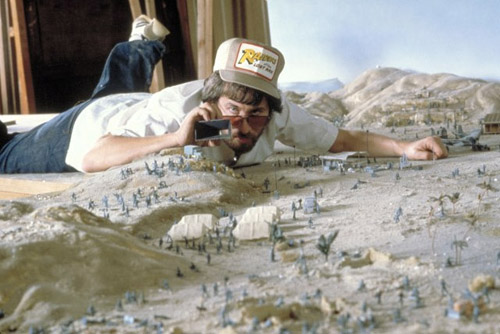

Even in his teen years, Spielberg accomplished big production values with inspired resourcefulness. In filming a story about WW2 fighter pilots, he used his father’s access to military equipment to achieve an unbelievable degree of authenticity.

He even went so far as to shoot in the cockpits of grounded fighter planes, which he shot using 8mm black-and-white film seamlessly intercut with stock footage of aerial dogfights. I did something similar in one of my own early shorts, whereby I cut in the climactic explosion shot from Terence Young’s DR. NO (1962) when I needed a big explosion to happen in my story.

There’s a tactile joy and magic to editing when you first discover it, and the purity of youth makes for some charming resourcefulness. It was this very resourcefulness that would propel Spielberg to unparalleled heights throughout his career.

Also in 1961, Spielberg filmed the short ESCAPE TO NOWHERE, inspired by a World War 2 battle that occurred in East Africa. Spielberg shot it on 8mm color film with his friends and siblings in the dusty Arizona chaparral that was his neighborhood’s backyard.

Originally running 40 minutes long, there’s only a 2 & ½ minute excerpt that exists for public eyes. The excerpt depicts a heated battle, with no real coherent sense of geography or who’s who.

Due to the limitations of childhood, Spielberg’s actors are all dressed the same—army pants and helmets, and white t-shirts—and probably all are using the same handful of rifles. Young boys frequently play war in their backyards, filling in the majority of the battle with their imaginations.

ESCAPE TO NOWHERE is just like playing war as a kid, only fully realized. There’s a palpable homemade, amateur element to the film, understandably due to Spielberg’s resources at the time, but he makes up for it in sheer zeal and energy.

However, even at age 13, it’s striking to see his craftiness with homegrown special effects (stomping on shovels to kick up dust in simulated landmine explosions) and his imaginative approach to composition and camera movements—one handheld tracking shot is clearly intended to emulate a dolly, etc. It’s unclear whether the soundtrack on the excerpt—Wagner’s “Ride of The Valkyries” laid on top of a booming sound effects mix—accompanied the original film or was the work of whoever uploaded it to Youtube.

If it’s original, it shows Spielberg’s innate sense of spectacle and understanding of sound’s crucial role in film. It also predates his filmmaking contemporary Francis Ford Coppola’s infamous use of it in APOCALYPSE NOW (1979) by nearly twenty years.

Regardless, ESCAPE TO NOWHERE is a captivating and chaotic look at Spielberg’s fascination with World War 2 and how it shaped his approach to one of his finest films, SAVING PRIVATE RYAN.

Spielberg’s success as a filmmaker can’t be attributed to talent alone. He’s also proved himself as a cunning businessman and studio head. The long, (somewhat) healthy life of his own Dreamworks Studios is a testament to his grasp on the business side of filmmaking.

The origins of this aspect of his career can be traced back to his very first amateur feature film: 1964’s FIRELIGHT. In shooting a story about alien UFO’s terrorizing a small town (a forerunner to CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND), the 18-year old Spielberg set about making his first serious-minded film.

By this point, he knew that filmmaking was what he wanted to pursue as his career, and he was eager to get started on it. Shooting again with friends and family in Arizona, Spielberg put in $600 of his own money, emerging with a 150 minute long 8mm sci-fi epic.

FIRELIGHT became his first work viewed by a paying audience when he booked a screening at the Phoenix Little Theatre and charged 75 cents a seat. The budding entrepreneur turned a profit of only one dollar, but the fact remains that he had nonetheless turned a profit. It was a formative night in what would become an exceptional career.

Unfortunately, only a few minutes of FIRELIGHT are available for public view, and they seem to be random excerpts taken throughout the film. Again, however, these excerpts show a young Spielberg already in control of his craft, with his now-signature style beginning to find its footing.

Unfortunately, only a few minutes of FIRELIGHT are available for public view, and they seem to be random excerpts taken throughout the film. Again, however, these excerpts show a young Spielberg already in control of his craft, with his now-signature style beginning to find its footing.

The excerpts depict a dark film, with high-key lighting giving an unworldly glow to the proceedings. A variety of suburban, Americana character archetypes—the high school couple on a date in dad’s pickup truck, the young child playing in the yard, etc.—look up in awe as a red flare of light (standing in for the UFO) slowly jerks across the screen.

The sound design reflects the grand cinematic ambitions Spielberg has for the story, even if his limited visual resources can’t quite pull it off. It’s a curious prelude to his further exploration of alien life forms in films like CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, E.T: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL and WAR OF THE WORLDS (2005).

During this early amateur period, Spielberg made another short, the unfinished SLIPSTREAM (1967). Like THE LAST GUNFIGHT before it, it is unavailable for public viewing so I can’t consider it in the context of Spielberg’s development. It’s unclear to why the film was unfinished, but it probably owes to the fact that the young Spielberg was embarking on college, and the significant life changes it brought likely derailed the project.

During this early amateur period, Spielberg made another short, the unfinished SLIPSTREAM (1967). Like THE LAST GUNFIGHT before it, it is unavailable for public viewing so I can’t consider it in the context of Spielberg’s development. It’s unclear to why the film was unfinished, but it probably owes to the fact that the young Spielberg was embarking on college, and the significant life changes it brought likely derailed the project.

While Spielberg’s amateur work is scarce, the scraps available to us give intimate insight into the mind of an auteur who would go on to help make cinema what it is today. By starting out in childhood, Spielberg got a head start over his contemporaries.

He had already been making movies for ten years by the time he received attention for his 1968 short AMBLIN’. Thusly, when Hollywood came knocking, Spielberg was ready.

AMBLIN (1968)

When I first decided that I wanted to make films for a living (which was at the tender young age of eleven), I immediately began to dream about one day moving to Los Angeles to pursue that career. I knew that I’d have to go to film school, and had heard that the School of Cinema-Television at the University of Southern California was the best in the country.

Naturally, that meant that I would go there. For the next seven years, all my filmmaking efforts, as well as my school performance, were aimed towards the singular goal of getting into USC. Of course, you can imagine my crushing disappointment when that rejection letter came in the mail one sunny spring day. As fate would have it, I was destined for a detour in Boston to study film at Emerson College before moving to the balmy climes of southern California.

It’s impossible to tell whether a USC education would have had a different impact on my still-budding career, but funnily enough, next year I’ll be marrying a Trojan, so in a way I still get to have my cake and eat it too. I say all this because in those dark days following the USC rejection, I had one bright, shining beacon of hope to guide me onward: the knowledge that director Steven Spielberg, inarguably the most successful filmmaker of all time, had been rejected from USC too (twice!).

By virtue of his association with high-profile USC alumni like George Lucas and Robert Zemeckis, many people simply assume that Spielberg had gone there as well. Instead, he attended California State University at Long Beach and dropped out altogether after his sophomore year (he later finished his degree in 2002). I was reassured in the notion that, if he could accomplish all that he has without the aid of a USC education or family connections to the industry, then surely so could I.

Of course, Spielberg experienced his own trials and tribulations to get where he is today. During his late teens and early twenties, Spielberg was desperate to break into the movie business any way he could.

Rather famously, he took a tour of the Universal lot and ditched the tram halfway through, wandering around for hours and making friends with various people who then allowed him to sneak back onto the lot whenever he pleased. This bold move on his part would indirectly lead to him getting an audience with Universal VP of television of production, Sid Sheinberg—a story that I’ll get into a little later.

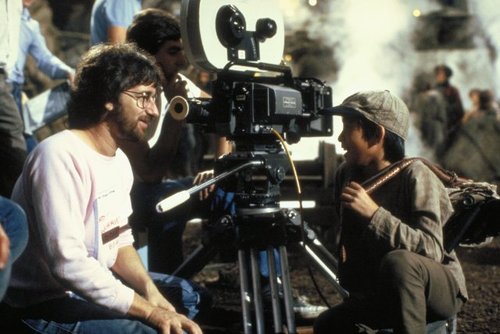

All this sneaky stuff would be for naught if Spielberg had nothing to show for his own talents. Obviously, he couldn’t show his amateur home movies (except maybe 1964’s FIRELIGHT) and still be taken seriously. To that end, he began writing a short script about a young man and woman discovering each other and themselves on a hitchhiking trip to California. Spielberg met an aspiring producer named Denis Hoffman who was looking to fund a film, and they decided to begin work on what would eventually become Spielberg’s first 35mm short: AMBLIN’ (1968)

Presented completely without dialogue for the entire duration of its 25-minute running time, AMBLIN’ is a light-hearted romp through the Joshua tree-dotted landscapes of the Mojave Desert. Actor Richard Levin plays the unnamed young man, and Pamela McMyler plays his free-spirited female companion.

As they work together to hitch a ride to the coast, the woman coaxes the man into several rites of passage—like smoking pot and having sex in a sleeping bag, to name a few. All the while, the man carefully guards his guitar case, which only makes the woman more curious to find out what’s inside.

Shooting on a budget of $15,000 with a crew of college kids, Spielberg nevertheless makes the film feel professional and polished. Together with cinematographer Allen Daviau, Spielberg employs a blown-out aesthetic and sun-bleached color palette.

He resourcefully creates a grand sense of scale by composing his characters as lone figures against the expansive desert landscape (an effect somewhat dampened by the format’s limiting 4:3 aspect ratio). Spielberg’s camerawork is youthful and energetic to match the tone of story, using dolly shots, rack zooms, and handheld takes that evoke the experimental style of the New Hollywood movement with which Spielberg would later become associated with (a movement that itself was directly influenced by the bold cinematic transgressions of the French New Wave).

Michael Lloyd contributed the film’s score, which plays from end to end in place of dialogue. Lloyd’s work takes on a boppy, travelling vibe that sounds a lot like the easy-going folk/hippie rock of its day.

The folk-y/western theme song that plays over the opening credits is performed by a band called October Country, which conveniently happened to be one of the acts that producer Hoffman was managing at the time. Spielberg knew he was making a career game-changer, even if his disgruntled, unpaid crew didn’t.

He was so nervous during production that he reportedly puked every day before showing up on set. Despite the adverse conditions of the shoot, Spielberg came out with a finished film that he could use as a calling card.

This may not seem like that big of an accomplishment in today’s democratic age of filmmaking, where everyone has a short to their credit. But in 1968, the sheer cost of film stock meant that the pool of successful short film directors was pretty thin.

Spielberg had a leg up over the countless mob of LA wannabes simply by virtue of having something to show. This is where the aforementioned Universal connection comes into play.

After spending a summer getting to know various people on the Universal lot, a copy of AMBLIN’ found its way into the office of television VP Sid Sheinberg. Sheinberg was so impressed by the film that he signed the young Spielberg to a seven-year TV-directing contract. With that, the ambitious 22-year-old filmmaker had officially become a paid director. Achieving his dreams came at a cost, however—Spielberg had to drop out of college and put his education on hold. Real-world directing would be his film school now.

AMBLIN’ continued playing an influential role in Spielberg’s career by giving him the name for his first big production company, Amblin’ Entertainment. Amblin’ Entertainment has gone on to become one of the most iconic shingles in cinematic history—every kid who grew up watching movies in the 90’s has that logo (featuring the classic E.T. bicycling against the moon imagery) seared into their memory.

For the film that launched the biggest career in the game, AMBLIN’ has been surprisingly neglected. Judging by the stream available on Youtube, it hasn’t been officially released since the days of VHS. The well-worn copy available online has warped the presentation to a far-from-pristine state.

Given the extensive number of film restorations that Universal has been commissioning for its centennial celebration, it strikes me as odd that they wouldn’t preserve the debut work of its most valuable director. Perhaps Criterion will come to its rescue if it ever decides to give one of its coveted spine numbers to a Spielberg film.

For a film that’s now more than 40 years old, AMBLIN’ comes off as very dated due to its focus on late 60’s youth culture. Its poor visual presentation doesn’t help either. However, it is still a fascinating document by the world’s most successful filmmaker at the shaky beginnings of his career.

A far cry from the big-budget blockbuster spectacles that would make his name, AMBLIN’ is a quiet, intimate story with themes of discovery and innocence against the wider world—themes that would come to define Spielberg’s style and chart the course of his career.

NIGHT GALLERY: “EYES” EPISODE (1969)

American screenwriter and TV producer Rod Serling was a household name in the 1960’s, due to the massive popularity of his show “THE TWILIGHT ZONE”. This was not only due to the strength and quality of his work, but also due to the fact that he introduced each segment on-screen in his now-signature enigmatic showman’s demeanor.

In 1969, Serling created a second series titled NIGHT GALLERY that would serve as another outlet for his exploration of the weird, the strange, and the macabre. It was also around this time that Side Sheinberg,

Universal’s VP of Television, signed the young, twenty-three year-old director Steven Spielberg to a television contract after being impressed by his short film, AMBLIN’ (1968). To his credit, he was wise enough to see both Spielberg and Serling’s new series as complementary to each other, and thus Spielberg found himself with his first paid directing assignment: one of the three segments that would make up a televised anthology movie/pilot.

Spielberg’s segment is entitled “EYES”, and tells the story of a rich, elderly, and vainglorious blind woman who contracts her (very reluctant) doctor to perform an eye transplant surgery that will restore her vision, albeit for only twelve hours. The eye comes from some sad sack who is desperate to pay off his own debts, unaware that he’s losing his eyesight forever in exchange for a paltry sum that will be gone just as soon as he’s paid.

The surgery goes off seemingly without a hitch, only for the woman’s new eyes to fail her shortly after exposing them to light. Subsequently, she is plunged into a dark nightmare of a night that will take away her very sanity.

As Spielberg’s first big directing job, “EYES” naturally marks the first occasion that Spielberg works with big Hollywood talent. And during that time, it didn’t get much bigger for him than working with Oscar-winning screen legend Joan Crawford, star of such seminal Hollywood classics as MILDRED PIERCE (1945) and WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? (1962).

In one of her last high-profile performances, Crawford looms large on NIGHT GALLERY’s small screen as the blind Mrs. Menlo, who lives on the top floor of her large Park Avenue apartment complex like a Queen lording over her castle. Being as such that she is the sole tenant in the entire building, however, she has no subjects to rule over besides her trusted doctor.

Crawford’s performance is “old-school Hollywood” big, much like Gloria Swanson in Billy Wilder’s SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950). By this point in time, the old guard of Hollywood’s Golden Age starlets were just that: old. A lifetime of excess and indulgence had made them grand old dames, stubborn in their ways and their collaborator choices.

Upon learning that the young hotshot Spielberg would be directing her on his first time at bat, Crawford reportedly called up Sid Sheinberg to demand he be replaced by someone more experienced. It could’ve ended Spielberg’s career before it even begun. Fortunately for him (and us), Sheinberg talked Crawford down from the ledge and backed his man.

Despite this early hiccup, Crawford and Spielberg got along famously, even so far as keeping in touch for the remainder of her lifetime.

Television isn’t the most director-friendly medium, in that directors are subject to an aesthetic and tone predetermined by the producer or show runner. Since Spielberg was helping to launch a new show, he enjoyed much more freedom in shooting his segment.

Television isn’t the most director-friendly medium, in that directors are subject to an aesthetic and tone predetermined by the producer or show runner. Since Spielberg was helping to launch a new show, he enjoyed much more freedom in shooting his segment.

While he most likely didn’t have a hand in creating NIGHT GALLERY’s recurring moments (the spooky opening titles or Serling’s on-screen segment introduction), Spielberg gives his segment a bold, colorful, and bright look that sets it apart from the other stories.

Working with cinematographers Robert Batcheller and William Margulies, Spielberg opts for a classical approach to match the elegant production design by Howard E. Johnson. A neutral color palette accentuates bold punches of color, and high-key lighting adds a lurid quality to the 35mm film image.

Camera-work is fairly reserved, employing both dolly shots and locked-off static shots. Spielberg covers most of the action in well-composed, evocative wide shots, which gives a greater heft to his strategic close-ups. Despite the sober “establishment” approach, Spielberg was able to incorporate elements from the transgressive, burgeoning French New Wave movement into his coverage.

He uses a well-placed series of jump cuts to add intensity to an already-intense outburst by Crawford, and creates an expressionistic climax by swapping out a traditional set for an inspired blend of sound design and well-placed pools of light that cut through a harsh blackness. In doing so, Spielberg shows a remarkable aptitude for turning the ordinary into anything but.

The eye-swapping conceits of the story are highly reminiscent of the same conceits that would shape the plot of Spielberg’s sci-fi masterpiece MINORITY REPORT over thirty years later. The imagery of gauze bandages wrapped around the eyes is consistent between both works, and the imagery of eyes in a larger sense recurs throughout Spielberg’s filmography, like the iconic T-Rex pupil dilation shot in JURASSIC PARK (1993).

For his first real directing gig, Spielberg’s contribution to NIGHT GALLERY is a curious rarity in the pop cultural wasteland. The series is highly-regarded amongst cult fans, but even then, it’s difficult to find the TV movie that launched prior to Season 1.

To view it, I had to venture into the dark corners of the internet to salvage an old VHS rip with Spanish subtitles. Hardly the sort of preservation and reverence you expect would be given to the first professional work of the biggest director in mainstream American cinema, but these are the times we live in.

EYES is a humble beginning for Spielberg, a project overshadowed by Serling’s then-celebrity and influence. His natural talent is immediately apparent; one could be forgiven for thinking that he had already been a working television director for several years.

Due to the quality of his segment, Spielberg would be called to work on several other shows (including another episode of NIGHT GALLERY), and his status as a “director to watch” was affirmed.

NIGHT GALLERY EPISODE: “MAKE ME LAUGH” (1971)

In 1971, the young television director Steven Spielberg was invited back to the scene of his first major directing gig, ROD SERLING’S NIGHT GALLERY, for another crack at bat. His second episode, titled “MAKE ME LAUGH”, told the story of a failing comedian (Godfrey Cambridge) who would give anything just to make people laugh.

By chance, he runs into a self-described “miracle guru” (Jackie Vernon) who reluctantly grants him his wish after his pleas for caution fall on deaf ears. Sure enough, the comedian shoots to stardom off of his ability to make guts bust at the slightest of utterances.

But he soon finds that this dream comes at a price—no one can ever take him seriously. For a comedian, this would be all good and well, but his gift becomes a curse when he loses out on a serious dramatic part on Broadway and, subsequently, the career acclaim and reverence that he truly desires.

There are a few notable performers in the piece, led by Godfrey Cambridge, who excels at appearing sweaty and desperate as his dreams unravel before his very eyes. Tom Bosley, who previously appeared for Spielberg in his “EYES” NIGHT GALLERY episode, plays the comedian’s mild-mannered agent.

Real-life comedian Jackie Vernon seems an odd choice to play a turban’d mystic/sage, but his goofy cadence brings an unexpected flavor to the proceedings. And finally, Al Lewis—who’s better known as Grandpa Munster—makes a cameo as a gruff nightclub owner with little patience for the comedian’s failings.

As far as NIGHT GALLERY episodes go, “MAKE ME LAUGH” is probably the most straightforward and non-surreal. Spielberg presents the story in a reserved manner with classical camera moves and non-distracting locked-off shots.

Little of the New Wave flourishes that dotted his camerawork in “EYES” shows up here, but he does utilize the scale-generating power of a crane for his ending shot. I mention this crane shot mainly because it hints at Spielberg’s own internal ambitions and what was likely his nagging desire to graduate from TV into big-budget feature film making.

Even the most pedestrian of coverage angles, the close-up, possesses a strange kind of subliminal vocation in its composition. Spielberg was trying very hard to be noticed while simultaneously “coloring inside the lines”.

“MAKE ME LAUGH” doesn’t show much in the way of growth for young Spielberg, but it doesn’t necessarily have to. These were journeyman years for the director, whereby he cut his teeth over the safety net of a predetermined aesthetic and a support group of producers, supervisors, editors, and other craftsmen.

The urge to get into features was growing stronger, but he was only midway through his television phase when he made “MAKE ME LAUGH”. I imagine that he felt like he was spinning his wheels, but with each successive television gig, Spielberg was growing stronger and more confident. When his day in the sun came, he would be ready.

COLUMBO EPISODE: “MURDER BY THE BOOK”, AND OTHER TELEVISION WORKS (1971)

The year 1971 was a fateful one for director Steven Spielberg. The young hotshot had already racked up some impressive credits on ROD SERLING’S NIGHT GALLERY and MARCUS WELBY, MD in the years prior, but 1971 in particular saw the production of no less than 6 television projects—one of which became his break-out into features.

First up is THE NAME OF THE GAME, a series that was well into its third season when Spielberg came onboard to direct an episode titled “LA 2017”. The show revolved around the magazine industry and was set in the present day, but “LA 2017” used the “it was all a dream” conceit as an excuse to transport the show’s main character (Gene Barry) into a future version of Los Angeles.

Why they did this, I haven’t the slightest clue. Anyways, the series appears to be unavailable on DVD, and the only version of the episode that exists online is a short fan-made trailer featuring scenes from the episode. Going off that, it’s quite apparent how much of a deviation it is from Spielberg’s previous television work.

As his first project with a feature-length running time, Spielberg uses imaginative, slightly kitschy production design to create a dystopian Los Angeles of the future. Based off the trailer, it seems to be populated by geriatric hippies who perform in underground rock clubs.

This makes a strange kind of sense, given the fact that most of pop culture’s predictions about the future are really just projections of the present times they’re made in. As the father of the modern blockbuster, Spielberg’s career has understandably been heavily associated with visual effects.

“LA 2017” marks the young director’s first professional use of visual effects, as well as his first professional dabble in the sci-fi genre. Judging by the glimpses given in the trailer, Spielberg’s visual style at this time seems to be coalescing around evocative low-angles and compelling close-ups, with camerawork reminiscent of—and no doubt influenced by—the French New Wave movement that was then-unfolding across the pond.

After the successful reception of “LA 2017”, Spielberg contributed two episodes to the unsuccessful television show THE PSYCHIATRIST. His episodes, “THE PRIVATE WORLD OF MARTIN DALTON” and “PAR FOR THE COURSE”, were unavailable for viewing, as is the entire series.

Later that year, Spielberg landed a plumb job in directing the series premiere of COLUMBO, a property that had already enjoyed a few successful TV movie incarnations. Featuring well-known film actor Peter Falk as the titular detective, COLUMBO bucked the trend of most television serials at the time by regularly crafting movie-length episodes.

Each COLUMBO episode was self-contained, further leading to its cinematic nature. Spielberg’s episode, titled “MURDER BY THE BOOK”, featured a “perfect crime” mystery, wherein Columbo cracks the case of a brilliantly covered-up murder.

Jim Ferris (Martin Milner) is one half of a writing team behind a successful series of murder mystery books, but in reality he is the one that does all of the writing. His partner, Ken (Jack Cassidy) enjoys all of the benefits of the series’ success without actually contributing anything.

This poses a problem when Jim decides to go solo, which would dry up all of Ken’s income. Naturally, Ken kills Jim and covers it up using a ruse from one of their stories. Once the murder is discovered, Columbo gets on the case, immediately setting his sights on Ken as a suspect and unraveling his so-called “perfect plan” quite easily.

Ken was so confident in getting away with murder, he neglected to mind that his meticulous plan was laid right out in the open—inside Jim’s own books—for Columbo to find. Despite being a series premiere, Spielberg still adheres to the aesthetic established in previous COLUMBO TV movies by going with a naturalistic, high contrast look.

Dolly and crane-based camera movements give the episode a high degree of production value, while Spielberg’s use of a handheld, documentary aesthetic in the crime-scene sequence further points to his fascination with the French New Wave. One of the great things about watching old TV shows and movies shot in Los Angeles is recognizing certain landmarks and how their surroundings looked at the time of production.

I remember seeing an aerial shot of downtown LA in Michelangelo Antonioni’s ZABRISKIE POINT (9170) and being blown away by how non-existent today’s skyline was back then. Similarly, I recognized the locale of an early scene in “MURDER BY THE BOOK”, which featured a building on Sunset Boulevard that I came to know very well after working inside of it for two years.

However, in COLUMBO this building was still under construction, having only reached the steel frame stage. It has no real bearing on my analysis of Spielberg’s work here, but I couldn’t resist mentioning it.

Spielberg would go on to direct an episode for the series OWEN MARSHALL: COUNSELOR AT LAWcalled “EULOGY FOR A WIDE RECEIVER”. This too wasn’t available for viewing at the time of this writing, so “MURDER BY THE BOOK” is the latest example of Spielberg’s episodic work.

However, it is appropriate given the fact that it was his work on COLUMBO that directly resulted in Spielberg being hired for the television film DUEL (1971). To him, it was just another TV gig, but fate had other plans.

DUEL (1971)

By 1971, the young Steven Spielberg had made significant headway as a television director. His eye started to wander into theatrical feature territory, but he was uncertain how he’d get there. Until a better opportunity would arise, the best he could do was approach each TV gig with the same kind of attention to detail that he would lavish on a work of cinema.

Ironically enough, Spielberg’s first foray in theatrical exhibition wasn’t so much a calculated move as it was stumbling headlong into it. After his successful foray into feature running times with his “MURDER BY THE BOOK” episode of COLUMBO earlier that year, Spielberg’s assistant brought him a short story written by I AM LEGEND author Richard Matheson about a man stalked on a desert highway by a trucker stricken by a serious case of road rage.

The young director was immediately enamored with the simplistic, yet almost Hitchcock-ian story conceit. Using the rough cut of his COLUMBO episode as proof of his ability, he acquired the rights to the story and set it up at ABC as a Movie of The Week.

Spielberg’s adaptation, DUEL, is ferocious in its simplicity. A mild-mannered salesman named David Mann (stage and screen veteran Dennis Weaver) is driving through the California desert en route to an unspecified “appointment”.

He encounters a monstrous truck lumbering slowly ahead of him, so he drives around to pass the behemoth. Unfortunately, this incites a murderous rampage of terror as the truck stalks David’s car across the vast expanse of desert.

Literally driving for his life, David soon realizes the only way to rid himself of the menace is to confront it head-on. Dennis Weaver gets the majority of screen-time to himself, as his co-star is the faceless hulk of a truck looming ever closer in his rearview mirror.

To this end, Weaver ably holds our attention and interest like one would endeavor to do in a one-man stage show. His transformation from mild-mannered pushover, to terrified impotent, and finally to cunning fighter is compelling to watch.

The truck itself, however, is just as much a leading character as David is. It becomes a primal force of nature, belching black smoke into the sky and bearing down in David’s rearview mirror like some vengeful beast. Spielberg brilliantly never shows the actual truck driver at the helm, thus giving the truck itself a malevolent sentience.

A lot has been written in recent times about “the decline of men”. In a nutshell, the phenomenon is described as men relinquishing their “traditional” status as heads of households, breadwinners, masters of the universe, etc. Analysts like to argue that distractions such as video games and pornography have lulled men into a state of submissive complacency, in addition to abdication from parental and social responsibilities.

Now, I personally think a lot of that talk is bullshit, but the greater conversation does have a lot of valid points. Watching DUEL, I noticed several corollaries that lead me to believe this isn’t a recent conversation at all.

One of the major themes running through DUEL is this concept of emasculation. David Mann (the last name isn’t coincidental) is initially depicted as something of an ineffectual pushover. The truck that chases after him is a symbol of a primal masculinity, roaring like hellfire as it mercilessly hunts down its prey.

Those are the obvious signs, but Spielberg cleverly peppers in several other subtle moments that reinforce the theme. For instance, the film begins with audio from David’s radio: a man calls into a local radio show and expresses his paranoia over his neighbors getting a hold of his tax return and finding out that he has filed his family’s taxes with his wife designated as the head of the household.

Yet another instance finds David entering a roadside diner to gather himself together and eat some lunch, only to find that the trucker that’s been terrorizing him is in there too. Spielberg blocks the action so that David is sitting alone in the corner of the diner, a section that’s been painted entirely with pink.

The image of a grown man relegated to “the pink corner” is understandably emasculating, made even more so by the curious glances he receives from the line of grizzled truckers eating at the bar. David’s internal monologue, rendered as a breathless voiceover, also reinforces the story’s challenge of his masculinity.

He describes his ordeal as being “suddenly back in the jungle”, with the stakes being reverted to a primal state of life or death. He is the hunted, and he has to become the hunter if he is to survive.

While DUEL was intended for television exhibition (the 1.33:1 aspect ratio is a dead giveaway), Spielberg strives for a grandly cinematic approach in his collaboration with cinematographer Jack A. Marta. The 35mm film image looks as sun-baked as its desert setting, with saturated orange, red and brown tones burnt into the high-contrast frame.

The camerawork evokes the relentless juggernaut pursuing David by using a restless mix of cranes, rack-zooms, and car-mounted POV shots that speed along the cracked two-lane blacktop. Since this is the first professional work where Spielberg is truly calling the shots in terms of style, he indulges in a variety of nouvelle vague techniques that make DUEL one of the most visually stylized films he’s ever made.

In creating the film’s score, Spielberg turned to composer Billy Goldenberg, who had scored early television works for the director like ROD SERLING’S NIGHT GALLERY: “EYES” (1969) and COLUMBO: “MURDER BY THE BOOK” (1971). Goldenberg creates a driving, discordant score that would not be out of place in a Hitchcock film.

Furthermore, Spielberg uses a variety of bland, generic muzak for the in-radio music. By using source music that’s devoid of any personality, Spielberg reinforces the tamed, neutered aspect of David’s personality, as well as the film’s theme of masculinity on the wane.

Spielberg once said that he watches DUEL about twice a year so he won’t forget how he made it. He was only given ten days to shoot—a tall order when you are a relatively inexperienced director and want to shoot everything on location. He had to fight to shoot the film in the way he wanted.

In those days, television simply wasn’t given the same kind of care and consideration that cinema enjoyed. Most directors would have shot the majority of DUEL on soundstages using chintzy rear projection techniques, but Spielberg wasn’t like most directors.

He barnstormed through the shoot so fast, that it’s actually something of a miracle that it turned out this good.

DUEL is consistently rated as one of the best television films ever made. We all know the stigma that comes with the Movie Of The Week format, so the fact that Spielberg worked so hard to transcend it as a testament to his love for the craft. When it aired, it scored some of the biggest ratings ever—even by today’s standards.

DUEL is consistently rated as one of the best television films ever made. We all know the stigma that comes with the Movie Of The Week format, so the fact that Spielberg worked so hard to transcend it as a testament to his love for the craft. When it aired, it scored some of the biggest ratings ever—even by today’s standards.

In Europe, it was released theatrically in cinemas after Spielberg shot a few extra sequences to pad out the running time. Its association with the cinematic medium has become so entrenched over time that it is commonly thought of as Spielberg’s first feature film.

DUEL comes off as understandably dated now, but the action is still as pulse-pounding as the day it came out. Its success showed that Spielberg was capable of making a killer film, and that his days in television were numbered. Indeed, the road ahead was paved with the promise of greater things.

SOMETHING EVIL (1972)

Spielberg’s first television movie, 1971’s DUEL, was a big success—even going so far as to screen theatrically in European cinemas. Before he could go headlong into features however, there was still the matter of that little seven-year TV contract he signed for Universal.

The very thing that had kickstarted his career now held him back from reaching new heights. In 1972, Spielberg once again tackled a Movie Of The Week, this time for CBS. Capitalizing on a surge of fascination with demonic possession and exorcism brought about by the publication of the infamous novel by William Peter Blatty (I’m talking about “The Exorcist” of course), Spielberg and CBS embarked on a little horror tale called SOMETHING EVIL.

SOMETHING EVIL is pretty standard as far as horror films goes. An idyllic, nuclear American family (and almost always white) moves into their dream home in the country—in this incarnation, rural Pennsylvania. Soon enough, the wife begins hearing strange sounds at night, and before she knows it, she’s caught in the grip of a horrific demonic possession.

In SOMETHING EVIL’s case, the possessed is the family’s young son, and the mother must fight to save her little boy from Satan himself. The film stars Darren McGavin and Sandy Dennis as Paul and Marjorie Worden, respectively.

McGavin is the father who reluctantly leaves their home in NYC for Dennis’ impulsive plea to buy a country house two hours away. As he is frequently away on business for his high-powered career in advertising, Marjorie is usually alone in the house with the children. The performances of SOMETHING EVIL are not really noteworthy.

Uninspired at best. Dennis’s shrill Mid-Atlantic accent is grating on the ears, and I found her overall character to be really irritating. The usage of such stock tropes, even in the fledgling days of demonic horror stories, points to writer Robert Clouse’s utter disinterest in crafting a television experience that aspired to anything higher than its station.

SOMETHING EVIL could be considered Spielberg’s first (and only?) dabbling in the horror genre, except it’s really more of a melodrama than an outright scary story. It doesn’t boast a conventionally moody aesthetic, instead opting for a straightforward, unadorned visual presentation by cinematographer Bill Butler.

Unimaginative, sedate camerawork counters Spielberg’s reputation for inspired compositions and moves, save for a few evocative frames seen from a low angle. Despite the success of DUEL before it, SOMETHING EVIL has never been released publicly, so it’s hard to discern whether it looks any good or not.

The only version of the film that seems to be available is a badly-worn VHS dub loaded onto Youtube, which washes everything out into a smear of green and yellow. As a horror story, SOMETHING EVIL is completely ineffective, save for one singular thing.

Marjorie is woken up in the middle of the night several times by sounds of a baby crying. Naturally she gets up to find out what the sound is, and spooky-time commences. Nothing scary actually happens during these sequences, but that damn sound effect Spielberg uses is unnerving.

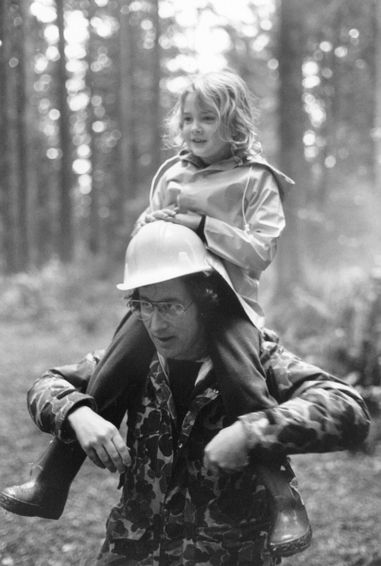

When I have kids, if they cry like that at night, they’re on their own. Nope nope nope. SOMETHING EVIL does contain a theme that runs throughout Spielberg’s body of work, that of the “absent father”. This theme is a reflection of Spielberg’s own difficult relationship with his father, and tends to manifest itself most strongly in stories with suburban, familial settings.

In SOMETHING EVIL, it isn’t exactly a broken home, per se, but Paul and Marjorie do have their share of marital troubles—namely, his rational disbelief alienating his over-sensitive wife. A long commute and a successful career in the city takes him out of the story for long stretches at a time, leaving Marjorie to face the forces of evil alone.

And in the end, it is only a mother’s touch that can save a young boy from possession. All told, SOMETHING EVIL is probably the most lackluster thing Spielberg had done up to that point (at least from what I’ve seen). As an exercise in horror, it falls flat on its face—making me wonder if that’s why Spielberg has never really attempted a true horror film in his career.

It’s not terrible, it’s just an uninspired hour of television that is as easily forgotten an hour later. It’s so generic that the writer couldn’t even be bothered to specify what the “evil” was that he was referring to in the title. SOMETHING EVIL is…. something bland.

SAVAGE (1973)

1971’s television film DUEL had generated director Steven Spielberg some significant attention from the cinematic world. Longing to answer their call, he frustratingly found himself still bound in place by his TV contract, which was nearing its end.

His impatience to graduate into feature filmmaking showed through in his 1972 TV film SOMETHING EVIL, and 1973 saw the production of the last television work that he was contractually obligated to. This project was SAVAGE, a feature-length pilot about a muckraking journalist named Paul Savage (Martin Landau) who investigates rumors of a sex scandal concerning a nominee to the Supreme Court.

Despite the lurid subject matter and its high-profile star, SAVAGE ultimately failed to be picked up as a series. To this day, it remains unreleased on home video, and the only version I could find on the internet was a five-minute cut-down of various scenes.

From what I can piece together, Spielberg attempted to make something slick and entertaining (unlike the indifferent SOMETHING EVIL before it). The 35mm film image is appropriately polished and lit by SOMETHING EVIL’s cinematographer Bill Butler.

Spielberg employs various low angle compositions and extensive camera moves as his aesthetic by this point had begun coalescing into something distinctly his own. Gil Melle is credited as the music composer, but I can’t tell if the music on the embedded Youtube video is from SAVAGE itself or was added for the cut-down.

If it’s original, then the light jazzy mood fits the sophisticated, urban sensibility Spielberg is after. Like that trailer of THE NAME OF THE GAME: “LA 2017” (1971), I can really only comment on what I can see from the cut-down.

Spielberg– already a TV veteran by age 27– seems to be in firm command of his faculties within the medium. It’s almost like he knows this is his last hurrah in this world (even though it wouldn’t be), and he wants to go out on a strong note. SAVAGE also finds him taking on the sort of serious, decidedly adult issues for that he would later explore in films like SCHINDLER’S LIST (1993), SAVING PRIVATE RYAN (1998) and LINCOLN (2012).

SAVAGE itself looks to be entertaining and strong, but its inability to amount to a successful series dooms it to the footnotes of a career that has all but overshadowed it.

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS (1974)

The success of 1971’s television film DUEL generated some momentum for director Steven Spielberg’s career, and as soon as his TV contract with Universal expired, he decided it was time to make the jump into feature filmmaking.

In 1974, he partnered with producers David Brown and Richard Zanuck to make a fictionalized film about a true event that took place in 1969-era Sugarland, Texas, whereby a young couple broke out of jail and abducted a police officer en route to steal their son back from the foster family he was given to by social services.

This film was THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS, and was a striking debut in the feature film realm for the young director. Boasting a box-office friendly star like Goldie Hawn and with the full financial backup of Universal Studios, Spielberg was able to make an earnest, crowd-pleasing take on the then-popular “lovers on the run” genre.

This genre in particular, kickstarted in 1967 by Arthur Penn’s BONNIE & CLYDE (1967), served as an ideal format for many of Spielberg’s directing contemporaries to make their debut—Terrence Malick had BADLANDS in 1973, and Francis Ford Coppola had THE RAIN PEOPLE in 1969, to name a few.

The story begins when Lou Jean (Hawn) smuggles her husband Clovis (William Atherton) out of the pre-release facility where he’s got just four months left on his prison sentence. Their intent is to get to Sugarland, Texas and reclaim the infant son that was taken away from them and placed into foster care when they were arrested.

Their escape is briefly foiled by a young police officer named Slide (Michael Sacks) until Lou Jean steals his gun and takes him hostage. As they make the policeman drive them to Sugarland himself, the couple incites a media frenzy and a police response of epic proportions.

As the sole recognizable “name” talent, Hawn anchors an eclectic cast of solid performances. Hawn plays well into type as a gum-smacking, feisty redneck queen who doesn’t take no for an answer. I’m familiar with Hawn mostly as an older actress, so it was striking to see her so young here, looking very much like her daughter, Kate Hudson.

The rest of the cast is relatively unknown to me, but I was impressed by their performances nonetheless. Atherton is appropriately jittery as Lou Jean’s anxious husband, Clovis. As Clovis and Lou Jean’s police hostage, Michael Sacks does a great job of portraying his conflicted emotions as he comes to befriend his captors.

In many ways, he is the film’s protagonist, as he undergoes the biggest transformation by the end of the film, which concludes on a shot of him in a moment of solemn contemplation beside a lake. And then there’s Ben Johnson as Sacks’ superior, Captain Tanner: a seasoned Texan cop whose sensitivity and expertise is challenged by Lou Jean and Clovis’ unpredictable streak of mayhem.

Spielberg fully embraces the opportunity of making a feature film by hiring the great Vilmos Zsigmond as his cinematographer. Zsigmond had already shot 1972’s DELIVERANCE for director John Boorman, but the man who would eventually lens Michael Cimino’s THE DEER HUNTER (1978) and HEAVEN’S GATE (1980) was still a young upstart when he collaborated with Spielberg on THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS.

Zsigmond is one of the best cinematographers to ever work with the anamorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio, a personal conclusion that’s evident in Spielberg’s film. The 35mm film image is high in contrast, with a dusty color palette evocative of the Texas setting.

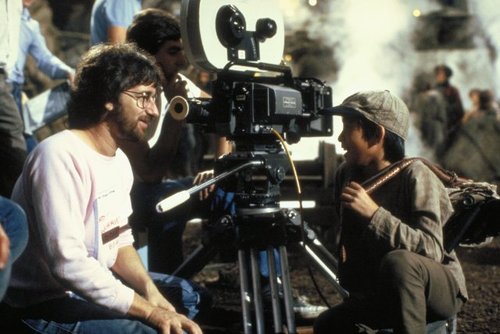

Spielberg had gained something of a reputation in the TV realm for placing a lot of his focus on camera movements and lens choices (more so than his peers), and his comfort with movement brings a great deal of energy to the film. He uses cranes, dollys, car-mounted POV shots, and complicated zooms to tell his story, as well as employing his now-signature low angle compositions to powerful effect.

Spielberg’s use of a surreal perspective technique in 1975’s JAWS, accomplished by zooming in while dollying out and first used by Alfred Hitchcock in VERTIGO (1958), is heavily referenced in film circles. What’s not mentioned, however, is that Spielberg first uses it in THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS, during the climax where snipers hide inside the foster family’s house and wait for the fugitive couple to approach.

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS also marks the first collaboration between Spielberg and world-renowned composer, John Williams. The two must have gotten along quite well during production, but I wonder if they had any clue that their collaboration here would result a lifelong friendship and several of the most iconic film scores ever produced.

Williams’ score for THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS is considerably less iconic, but still effective in setting Spielberg’s intended tone. It’s appropriately cinematic, utilizing various folk instruments like harmonicas and guitars to convey the country tone.

There’s even a strange kazoo-like instrument thrown into the mix, which reminds me of SESAME STREET, but seemed to be the sound du jour for this type of picture at the time. A modest selection of honky tonk source cues fill out the world and place the story inside of a palpable reality.

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS fits comfortably within Spielberg’s body of work as one of his more-daring films, ending on a note of ambiguity and uncertainty rather than the cathartic happy endings for which he’s known (and often derided). It also deals heavily with the concept of a broken family, a theme that runs heavily through Spielberg’s canon.

THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS fits comfortably within Spielberg’s body of work as one of his more-daring films, ending on a note of ambiguity and uncertainty rather than the cathartic happy endings for which he’s known (and often derided). It also deals heavily with the concept of a broken family, a theme that runs heavily through Spielberg’s canon.

Here, both parents are to blame for their separation from their son due to their criminal behavior—a stark difference from Spielberg’s other depictions where the father is the main absentee. It should be noted, though, that Goldie Hawn’s character is the instigator and key proponent of the plot; Atherton is initially reluctant to break out of his pre-release facility to fetch his son, and is more prone to doubt about the success of their mission.

In that sense, the father is not as invested in his family as the mother is, a notion that fits much more easily into Spielberg’s thematic conceits. Spielberg’s first true feature film was well-received, even going so far as to receive the Best Screenplay at that year’s Cannes Film Festival.

Most directors don’t enjoy the benefits of making their first film with the backing of a major film studio– a significant perk that made Spielberg’s debut more high-profile than it might have otherwise been. Interestingly enough, it hasn’t been paid as much attention in recent years by Universal’s home video department.

One would think that their most treasured director’s first feature film would be readily available in the high definition Blu-Ray format, but as of this writing, there are no plans for its release in the foreseeable future. Time has shown that many films are simply lost forever when they fail to make the jump to subsequent video formats, so we should be concerned that an important work of cinema is at risk of being lost beneath the tidal wave of the massive studio blockbusters that Spielberg helped to create in the first place.

As well as THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS was received upon its release, and as much of a career game-changer as it was for the young director, it could not begin to compare to Spielberg’s next film, which would change the face of Hollywood filmmaking forever.

JAWS (1975)

“We’re going to need a bigger boat”.

It was an unscripted line, an off-the-cuff remark during a take that somehow grabbed hold of an entire collective consciousness. The phrase has become a linguistic shorthand for confrontation with insurmountable odds.

It came from the 1975 film JAWS, a seemingly frivolous B-film about a Great White shark terrorizing a small beachside community. However, something about the movie tapped into a primal fear, generating an unconscious callback to those terrifying caveman days when we weren’t at the top of the food chain.

The fear generated by the film also leaked out into the real world: people refused to go swimming in the ocean, and beachside resort towns felt the sting of needed tourist dollars going elsewhere. The 28 year-old director Steven Spielberg couldn’t have possibly known what he was getting himself into when he signed on to JAWS.

He had seen the galley version of the eponymous novel by Peter Benchley in his producers’ office, and was drawn to it because of the thematic similarities to his 1971 TV film, DUEL. He responded to the struggle between anonymous, unknowable evil and an every-man protagonist, and saw an opportunity in JAWS to do for water what he did for the open road in DUEL. In the process, however, he’d inadvertently change the face of cinema forever.

JAWS is the kind of movie that most of the world’s population has seen, so we are all familiar with its story. Amity Island—an idyllic, fictional seaside community—finds itself besieged by a monstrous shark during peak tourist season.

The town’s chief of police, Brody (Roy Scheider) is tasked with subduing the shark threat while contending with familial troubles and hamstringing, bureaucratic challenges on his authority by a shamelessly negligent mayor. As the body count climbs and the town’s paranoia reaches a fever pitch, Brody teams up with a shark expert (Richard Dreyfuss) and a skilled fisherman (Quint) to take down the fish themselves out on the open water.

Spielberg and his producers (David Brown and Richard Zanuck) agreed that hiring a cast of well-known faces would ultimately take away the effectiveness of the shark. To that end, Spielberg sought actors like Roy Scheider to headline his shark tale.

Scheider is a strong everyman type, somewhat like Dennis Weaver’s mild-mannered protagonist in DUEL. Scheider gives a tremendous amount of paternal pathos to the part, and many times comes off as an authority figure not unlike Gregory Peck. The emotional through-line of JAWS is embodied in him, wherein one must conquer their own doubts and believe in themselves if they are to conquer unstoppable evil.

Robert Shaw plays Quint, a tough, salty bastard of a fisherman straight out of MOBY DICK. I was blown away to find that this was the same Shaw who terrorized Sean Connery’s James Bond as SPECTRE agent Red Grant in Terence Young’s FROM RUSSIA LOVE (1963).

In that film, he’s so young, fit and Aryan he qualifies as Hitler Youth, but only ten years later in JAWS, he’s just as believable as an old, burnt-out barnacle of a man. Shaw’s performance as Quint is just as iconic as the titular shark itself, although I will say that his accent is bewilderingly ambiguous. Is it Irish? Pirate? What?

Richard Dreyfuss plays Hooper, a shark expert from the Oceanographic Institute who’s called in because of his extensive knowledge of sharks. Dreyfuss is a fine foil to Scheider and Shaw, balancing out their measured machismo with an anxious, nerdy energy and hotheadedness.

JAWS is one of Dreyfuss’ earliest appearances, and one that almost never happened at all—he famously turned down Spielberg upon first approach, only to come crawling back to the production after convincing himself that his perceived “terrible” performance in a prior film would sink his career if it came out and he didn’t have something already lined up. Given Dreyfuss’ long and fruitful career since then, those concerns obviously never came to pass.

Rounding out Spielberg’s cast is Lorraine Gary as Ellen Brody and Murray Hamilton as Amity’s mayor, Vaughn. Gary balances out the prevailing machismo tone fairly well, but is ultimately never really given anything substantial to do besides fret and wail about the wellbeing of her husband.

Hamilton does a great job playing the opportunistic mayor archetype, giving the glad-handing character a smarmy, curmudgeon edge. JAWS finds Spielberg collaborating with Bill Butler, his cinematographer for the television films SOMETHING EVIL (1972) and SAVAGE (1973).

Freed from the boxy constraints of the small screen, Spielberg and Butler take full advantage of the panoramic real estate that the anarmorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio offers. For a film with such dark subject matter, JAWS looks surprisingly bright and sunny (as befitting a film set in an idyllic beach community).

Spielberg and Butler have cultivated a palette of neutral tones and striking primaries, especially the blue of the ocean/sky, and the red of blood in the water. In fact, red is used so little throughout the film that, when it bubbles up from the ocean depths, the effect is acutely arresting.

Spielberg makes no attempt to avoid lens flare, which not only gives the film its sun-bleached patina, but also marks the first instance of a visual conceit that would mark many of Spielberg’s works to come, as well as influence the filmmakers who would follow in his footsteps (I’m looking at you, JJ).

Spielberg’s first high-profile film utilizes surprisingly primitive camerawork, mainly because of the realities of location shooting under harsh conditions. For instance, the majority of the camerawork is handheld, due to having to counterbalance the roll of the ocean during boat-based sequences.

The well-documented technical difficulties with “Bruce” (the life-sized shark animatronic) resulted in a lot of unusable takes, so Spielberg embraced the Alfred Hitchcock approach and created a palpable atmosphere of suspense by showing the shark as little as possible. In a further nod to Hitchcock, Spielberg reprises the infamous VERTIGO zoom technique during a key beach attack sequence, and in the process created a reference-grade example of the technique that he first used in THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS.

Spielberg also ratchets up the tension by continually adopting the shark’s POV as it swims towards its prey. The underwater photography results in some of JAWS’ most enduring and iconic moments, but many film buffs will be able to see the influence of another underwater monster movie: Jack Arnold’s CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON (1954).

There’s one sequence in particular that illustrates the fundamental effectiveness of JAWS as well as the young Spielberg’s mastery of the craft. This is the aforementioned beach attack that occurs early on in the film. The scene assumes the POV of Chief Brody as he uneasily watches over a crowded beach blissfully unaware of the shark that lurks in its waters.

Spielberg gives us several character threads to follow—a dog, a young boy, an obese woman—and we see them through Brody’s eyes, with the uneasy tension that comes with knowing something everyone else does not. Spielberg, along with editor Verna Fields, strings together these vignettes into a suspenseful edit that commandeers our eyeballs and rumbles ominously in our gut.

In addition to the already-virtuoso nature of the sequence, Spielberg had initially planned to cover the entire thing in one continuous shot. While this conceit was highly indicative of traits shared by many a young, overconfident director, Spielberg was experienced enough to realize that there was little value in an approach that wouldn’t justify the considerable resources he’d need to accomplish it.

Instead, he used screen wipes of people walking past the camera as a way to seamlessly hide his cuts and punch-ins. The “Get Out Of The Water” sequence has become one of the most well-known in cinema, with Spielberg channeling the likes of Hitchcock and Sergei Eisenstein to remind us of the primordial power of montage.

For the most part, Spielberg brings back his core creative team from THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS for JAWS. The film was production designer Joe Alves’ second collaboration with Spielberg, and he would eventually go on to direct JAWS 3-D (1983) himself.

Editor Verna Fields won an Academy Award for her work on JAWS, and ironically, her work would prove to be too good—many critics attributed the film’s greatness to Fields’ touch instead of Spielberg’s. In somewhat of a dick move designed to assert his talents better on the next project, Spielberg would never again collaborate with Fields.

Spielberg’s collaboration with John Williams on the score continues, this time resulting in the first of many films together to boast a universally recognized theme. I don’t even have to describe the JAWS theme to you, because you’re playing it in your head right now.

Williams’ Oscar-winning theme has become the archetypical cue for looming danger, imitated and parodied countless times throughout pop culture. Spielberg initially thought Williams was playing a joke on him when he played him the two-note theme; he didn’t realize that he was the first one to be hearing what is arguably the most iconic film theme of all time.

JAWS was one of the most difficult shoots of Spielberg’s career, owing primarily to his insistence that the film be shot in the choppy waters surrounding Martha’s Vineyard. Between various instances of the shark animatronic malfunctioning, the cast and crew getting seasick, or even the Orca boat set sinking in the ocean, the production was literally a baptism by fire for the young director.

What was initially scheduled to be a 55-day shoot ballooned to 159, and Spielberg feared that he’d never work again because no one had ever fallen that behind on a schedule before.

Despite the hardships, however, fortune was smiling on Spielberg and his beleaguered crew. Much like the accidental capturing on film of a gorgeous shooting star (which remains in the final edit), there was a magical quality to JAWS that fundamentally connected with audiences.

Despite the hardships, however, fortune was smiling on Spielberg and his beleaguered crew. Much like the accidental capturing on film of a gorgeous shooting star (which remains in the final edit), there was a magical quality to JAWS that fundamentally connected with audiences.

When he was 18, Spielberg made a $1 profit from his film FIRELIGHT (1964). Ten years later, he found himself the director of JAWS: the highest-grossing motion picture of all time. If that’s not encouraging to aspiring filmmakers than I don’t know what it is.

All that success at such an early age has its drawbacks. JAWS gave Spielberg the freedom to pursue any film he desired, with final cut privileges to boot. Critical acclaim was pouring in alongside the box office receipts, and Spielberg began to believe that JAWS was not only bound for Oscar glory, but would sweep the whole damn thing.

There exists a fascinating home video of Spielberg, literally drunk off of his own confidence, watching the Oscar nominations come in on live TV—only for him to grow increasingly dejected as reality set in. Spielberg was so confident that he’d net a Best Director nomination that it’s almost disgusting to watch his hubris try to compensate for the subsequent deflation.

I didn’t think it was possible for anyone to be so unenthused about scoring a Best Picture nomination at that age. JAWS eventually won for Best Editing, Score and Sound, and Spielberg would go on to personal Oscar glory for SCHINDLER’S LIST (1993) and SAVING PRIVATE RYAN (1998), but I like to think this early disappointment was a learning experience for the young director, and turned him away from the entitled, bratty persona he was dangerously flirting with.

Ultimately, JAWS got something even better than the Best Picture Oscar when it was inducted into the National Film Registry as an important artifact of American culture by the Library of Congress in 2001. Even with its massive success, the rippling wake of JAWS’ release proved farther-reaching than anyone thought.

Before JAWS, the summer season was a cinematic dumping ground, a clearinghouse of sorts to make way for the big studio releases in winter. JAWS proved that summer could be an extremely lucrative season for profits, and thus the summer blockbuster phenomenon was born and an entire way of organizing the release calendar was fundamentally altered.

As the “first” blockbuster, JAWS became the benchmark against which all others were, and still are, measured. It reigned supreme as the highest grossing film of all time until two years later, when it was unseated by Spielberg’s friend, George Lucas, and his humble little space opera.

JAWS itself would go on to get three sequels, but with each one bringing in exponentially diminishing returns, the original remains the only entry that still enjoys relevancy today. While the rise of the summer blockbuster has resulted in several decades’ worth of cinematic memories, the coming of JAWS could be likened to letting the Trojan Horse inside the city walls.

JAWS’ Trojan Horse hid a battalion of studio executives, who used the film’ unprecedented success to leverage more power for themselves and ring in the age of high-concept spectacle films at the expense of thoughtful, auteur-oriented cinema. Spielberg is often regarded as an auteur in the same breath as Kubrick or Fellini (and rightfully so), but he is one of the few auteurs whose work has the unintended effect of displacing auteurs altogether.

When one entity rises, another must fall, and as JAWS gave rise to the modern spectacle film, it did so at great detriment to the adult, auteur-oriented cinema of the 1960’s and 70’s—ironically, the very kind of films that influenced Spielberg’s style in the first place. JAWS transformed Spielberg from a French New Wave fringe-kid into an establishment director, and it earned him just as many detractors as it did admirers.

All told, the effect of JAWS on Spielberg’s career cannot be understated. The little boy who had grown up in the Arizona desert with dreams of making movies was now the biggest filmmaker of them all. In doing so, he had—for better or worse– fundamentally changed Hollywood for decades, if not forever.

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND (1977)

After the breakout success of 1975’s JAWS, director Steven Spielberg earned the privilege to pursue any project he desired. Instead of attaching himself to whatever high-profile project was currently circulating around town, he chose to go back to his roots.

He updated the central idea behind his 1964 amateur feature, FIRELIGHT, a story about aliens descending on earth as told from the point of view of regular folks on the ground. Now with a big studio backing him—in this case, Columbia Pictures—Spielberg wanted to expand the story out on a grand scale.

After having already completed what is essentially the rough draft of the film in his youth, Spielberg’s third professional feature—CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND (1977)—is widely considered in several film circles to be his first master work.

Spielberg’s story begins in rural Indiana, when an electrical engineer named Roy sees (and subsequently chases after) a fleet of mysterious, blindingly-bright aircraft zipping through the night sky. He soon grows obsessed with seeing them again, and is consumed by visions of an ambiguous mountain shape.

Meanwhile, a woman named Jillian Guiler is having unexplained experiences of her own and seeks out Roy’s assistance after her son is abducted in the middle of the night. And on the other side of the globe, French scientist Claude Lacombe and his aides have come to the conclusion that a string of recent, mysterious phenomena are alien in nature.

These story threads converge at Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, where an elaborate facility has been constructed out of the geological formation’s bedrock in a bid to establish contact with the extraterrestrials. And once they do, their understanding of the universe is fundamentally altered.

Richard Dreyfuss, who had first appeared for Spielberg in JAWS previous, plays the protagonist, Roy Neary. In stark contrast to JAWS’ Hooper, Neary is a clean-cut family man, and something of a brute. His obsession with his mountainous visions spirals out of control, as does his grasp on his own family, who increasingly fear for his sanity.

This is easily one of Dreyfuss’ best performances, definitely his strongest one for Spielberg, who has come to use Dreyfuss as something like an avatar when the director decides to inject some of his own psyche into a character. Famed French New Wave director Francois Truffaut—helmer of the groundbreaking 400 BLOWS (1959)—was Spielberg’s first choice for the scientist Lacombe, and an unconventional one at that.

The nouvelle vague style (that Truffaut helped to invent) greatly influenced a younger Spielberg, who was elated to be working with one of his heroes. Truffaut plays Lacombe as a sophisticated, urbane academic, and holds his own mightily against Dreyfuss.

The inclusion of the acclaimed director to the cast lent a great deal of prestige to the picture, and even though one might reasonably expect two directors on one production would butt heads, Truffaut was gracious enough to submit himself entirely to Spielberg’s direction. Class act.

Dreyfuss and Truffaut are perhaps the biggest names involved in CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, although they can’t help but be eclipsed by the celebrity of Spielberg himself. The supporting cast doesn’t fare any better, but they turn in solid, effective performances.

As Roy’s wife, Ronnie, Teri Garr gives a good turn as a beleaguered woman who runs out of patience with her husband. However, the character itself is underwritten, and she ultimately fails to transcend the trappings of the archetype.

Melinda Dillon, as fellow believer Jillian Guiler, proves a better companion for Roy, but Spielberg forces a romantic angle between the two that feels forced. Veteran character actors Carl Weathers and Lance Henricksen– albeit before the “veteran” part– appear in brief cameos here, but their presence is more amusing than notable.

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND finds Spielberg re-teaming with his director of photography from THE SUGARLAND EXPRESS, the venerable Vilmos Zsigmond. The film’s visual language deals predominantly in beams of light, so Zsigmond adopts a high-key approach that accentuates the bright blue lights of the alien craft.

Once again, Spielberg shows little regard for lens flares leaking into his shot, which is suitable for the blinding wonder of the film’s starships. His embrace of lens flares has become massively influential in modern filmmaking, especially in the sci-fi genre.

One very striking aspect of the film’s cinematography is the numerous panoramic vista shots, complemented by the wider field of view afford by the anamorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Many of them are notable for the sheer number of stars visible in the night sky, which is next to impossible to capture using natural methods.

Instead, these shots were accomplished using the tried-and-true matte painting technique. While it can’t quite compete with the realism that CGI-based methods have to offer, matte painting has a charm all its own that adds to the timelessness of the story.

Spielberg’s camerawork in CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND marks a shift away from the experimental, nouvelle vague techniques that peppered his television and early film work, and towards a formalist, locked-off aesthetic (necessitated by the heavy use of pre-motion-control/in-camera effects shots like the aforementioned matte painting joins, etc.).

Another classic Spielberg technique finds its first concrete use here: the dolly-in “wonder/awe” shot. By this I mean: a character looks up in wonder/awe at something past the camera as it dollies in on the subject. This could be seen as an evolution of the low-angle compositions that Spielberg frequently uses, and has become a staple of his spectacle-based work.

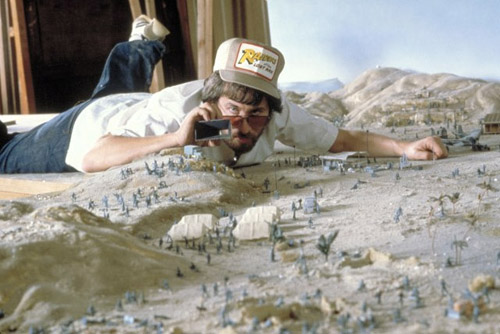

For instance, look at the compositions in the big “Devil’s Tower” reveal sequence in CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND compared to its counterpart, the brachiosaurus reveal in JURASSIC PARK (1993). They are essentially the same shot, with a colossal object slowly revealed from the point of view of the subjects as the camera cranes up and the score swells.