THE JERICHO MILE (1979)

Having lived in Los Angeles for over a decade now, I’ve had my fair share of run-ins with famous filmmakers. I once saw Ridley Scott marching down the New York backlot set at Warner Bros, cigar lodged firmly between gritted teeth as he barked orders at his entourage of assistants and aides.

I caught Quentin Tarantino taking the stage to promote INGLORIOUS BASTERDS (2009) at Amoeba Records in Hollywood. I shook an indifferent Nicolas Winding Refn’s hand during the wrap party for his 2016 film THE NEON DEMON.

During a brief footage review session at one of my old jobs, I gave Michel Gondry something of a minor existential crisis when my inability to quickly decipher his heavy French accent appeared to cause doubts about his own abilities.

Only a few weeks ago, I found Denis Villeneuve shopping at the Burbank Whole Foods. Exciting as any one of these encounters may have been, none of them compares to the time I saw director Michael Mann in person.

Mann — and his 1995 crime opus HEAT — has long been one of my personal favorites, so when it was announced that he would be present for a Q&A at a 20th anniversary screening of the film in a brand new 4K restoration, there was no way I was going to miss it (I wasn’t the only one who felt this way, judging by the snaking line that went on for several city blocks).

I thought myself rather lucky to score a seat as close to the stage as I did, but it wasn’t until the house lights dimmed that I realized the extent of my good fortune: maybe a mere half-row away, there sat The Man(n) himself. I don’t actually remember my first impressions of seeing the new 4K version of HEAT projected onto the big screen, because I was too busy watching Mann watch his own film.

And he was watching, rather intently; as if he was still searching out any lingering imperfections that needed correction. Mixed in with a crowd of his adoring fans, he appeared almost anonymous, his lips curled up into the faintest of smiles as his crowning achievement unspooled to cascading waves of clapping and cheers.

Though the increasingly-cold reception of his recent work suggests that his best days may lay behind him, Mann has nonetheless left an inestimable impact on American cinema as well as television. He’s best known for moody and violent crime dramas like HEAT, THIEF (1981), MANHUNTER (1986) or COLLATERAL (2004), but his sensibilities are versatile; his taste impeccable.

He’s just at home depicting the surgical procedures of a heist as he is fusing high romance with the historical epic (1992’s THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS), or spinning a gripping political whistleblower drama (1999’s THE INSIDER).

An entire generation of filmmakers have grown up under his influence, basking in a relatively compact — yet profoundly resonant — filmography that critic Matt Zoller Seitz, in his excellent video essay series on Mann, describes as “Zen Pulp”.

This influence has spread into television, beginning with a phenomenon of a TV show called MIAMI VICE that would come to define nothing less than the 1980’s itself. Mann’s continued involvement with the small screen throughout his career paved the way for today’s climate of world-class filmmakers working in the medium, helping to eliminate the deeply-entrenched stigma of television as a lesser, entirely-disposable art form.

To investigate the contours of Mann’s career is to make a case for the effectiveness of filmmaking as not just an act of expression, but as an act of discipline, meditation, and reflection that finds poetry in the hard lines that shape our urban landscapes.

Mann’s own story begins in Chicago, a defining setting within his work. Born February 5, 1943, Mann’s formative years were spent living in a blue collar neighborhood that doubtlessly shaped his artistic predilection for hard men with weathered faces and a strong work ethic. His upbringing in the Midwest eventually led him to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he studied English Literature.

Thinking it would be an easy way to pad out his credits, Mann decided to enroll in an elective film history course, where he unexpectedly found his very being moved by movies like Stanley Kubrick’s DR. STRANGELOVE: OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (1964), and GW Pabst’s JOYLESS STREET (1925)— the latter of which sent Mann away from the screening and into the night, having finally discovered that his life’s calling beckoned from the cinema.

The dawn of the 1965-1966 school year would find Mann at the London International Film School, where he stood to receive the kind of technical, hands-on training that he believed American film schools sorely lacked.

These earliest forays into filmmaking would evidence Mann’s natural talents, although they remain frustratingly elusive today; if they weren’t lost to mishaps, such as an 8mm short titled DEAD BIRDS that he misplaced in a move, then Mann has blocked their circulation outright.

This is the case with his two most formative shorts, JAUNPURI (1970) and 17 DAYS DOWN THE LINE (1971). Both were completed after his graduation, and established his profile as an up-and-coming filmmaker to watch.

The events leading up to JAUNPURI’s creation would evidence some of Mann’s signature traits, such as his dogged commitment to authenticity and a journalist’s ability to sniff out the universal truths in the passion plays between individuals and organizations.

Mann’s founding of his own production company after film school, Michael Mann Productions, was an act born not of creative expression, but of political urgency— with his studies complete, his visa wouldn’t be renewed and he’d likely face deportation back to America, where he faced either mandatory military service in Vietnam or a prison sentence as a draft dodger.

Knowing that operating his own business was sufficient grounds for a visa extension, the enterprising young director took his last few pounds and registered his company. He put his extension to good use, securing a job at the London offices of Twentieth Century Fox, where he supplemented his technical education with the equally necessary administrative aspects of physical production— budgets, breakdowns, etc.

In 1968, he talked NBC into sponsoring a trip down to Paris to document the May/June protests, where he was able to successfully persuade the rebel leaders to speak on television after the network failed to gain any traction themselves.

Mann channeled the momentum of this early success into the making of JAUNPURI, which subsequently won the jury prize at the Cannes Film Festival. After spending six years in Europe, the 28 year-old Mann returned to the United States and embarked on a 17-day road trip with Newsweek’s Marv Kupfer.

Their aim was to conduct filmed interviews with an assortment of workers from a variety of professions in the hopes of conveying the “philosophical hearts” of American men. The result was the 1971 short 17 DAYS DOWN THE LINE, a documentary wherein the interviewees are identified only by their occupation and not their names.

This artistic decision — a product of Mann’s fundamental belief that what people do is more important than what they say — would firmly establish a major trope evident throughout his work: characters whose core identities derive from their chosen profession and have subsequently constructed a rigid, near-monastic code of conduct for themselves.

The real-life prototypes of iconic Mann characters like HEAT’s Neil McCauley & Vincent Hanna or THIEF’s Frank are manifest here, their complex humanity distilled into an essence representative of a broader whole while abstractifying their individual experience and perspectives into the realm of philosophical and spiritual ideas.

17 DAYS DOWN THE LINE is further notable for its inclusion of music by Leo Kottke, a guitarist renowned for his contributions to jazz and blues — his musical presence establishing the foundation for Mann’s distinct artirist taste for eclectic blues, jazz and rock throughout his work.

While JAUNPURI and 17 DAYS DOWN THE LINE stand among Mann’s most high-profile (if severely under-seen) early work, his breakout as a professional director would come as a result of the strides he made in television.

After returning home, he sought out a mentor in the guise of Robert Lewin, then working as a head writer for the new TV series STARSKY & HUTCH. Lewin invited Mann to write an episode, and while the pilot had already been shot, the strength of his writing on the episode (titled “Texas Longhorn”) compelled the network to actually debut the series with his episode.

Mann capitalized on his newfound momentum in the writer’s room as a means to open doors to a directing career, subsequently embarking on a handful of writing and development efforts intended for the small screen. He wrote episodes for crime procedurals like POLICE STORY and POLICE WOMAN, and even created his own show in 1978 called VEGA$ (which he quickly disowned).

During this time, Mann was commissioned by producer Tim Zinnemann and celebrated actor Dustin Hoffman to adapt the Edward Bunker novel “No Beast So Fierce”. While Mann ultimately received no credit on the project (which eventually aired as a television movie called STRAIGHT TIME), the three months he spent at California’s notorious Folsom State Prison conducting research didn’t go to waste.

He was able to employ the copious notes, interview transcripts, and photographs he took in service of a Movie of the Week for ABC that would come to be known as THE JERICHO MILE— a rough and tumble portrait of a convict with a talent for running who is offered a shot at moral redemption (if not liberation) by competing in the Olympics.

The project had come to his attention after an initial Movie of the Week directing attempt, SWAN SONG, had gone south, and as a consolation prize of sorts, he received an invitation to comb through the network’s archives of unproduced material.

In THE JERICHO MILE, initially written by Patrick J. Nolan, Mann saw the opportunity to inject the clean-cut morality of the MOW format with a dose of the gritty, real-life drama he experienced behind the walls of Folsom.

With Zinnemann aboard as his producer, Mann commenced work on his first feature-length project, armed with a budget of $1.1 million and a mission to shoot inside the actual facilities at Folsom over the course of 21 days.

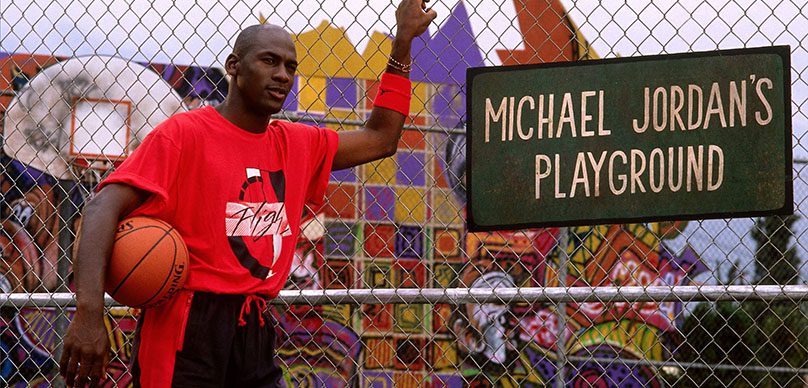

THE JERICHO MILE is notorious for the fact that it boasts the performances of actual convicts, who populate the background as extras in addition to contributing to bit speaking roles— a product of Mann’s skillful negotiation of a truce between the prison’s three major ethnic gangs, whereby every participant received payment at the Actor’s Guild scale.

Of course, a risk-averse network wouldn’t allow an unproven director like Mann to cast his film entirely with convicts, but Mann nevertheless would find convincingly-tough professional actors to fill out key roles. The largest of these finds Peter Strauss as the protagonist, Larry “Rain” Murphy, a stoic and stubborn man serving a life sentence for murdering his abusive father.

In prototypical Mann fashion, Rain’s identity is completely wrapped up in his state of incarceration— he is first and foremost a prisoner, serving hard time for a crime he would absolutely commit again if given the chance because he views it as a righteous act done for the greater good of his family.

In owning up to his act, he also owns up to its consequences; his morality may be relative, but at least it has clarity. Indeed, THE JERICHO MILE establishes the unique code of honor among thieves that forms the foundation of the classical Mann Protagonist.

The central characters of Mann’s filmography are almost-exclusively men, but cries of “sexism” have so far managed to elude him because his work — like that of Martin Scorsese’s — is fundamentally about masculinity: its passions, its poisons, the layered conflict dynamics and stoic principles that drive brutish behavior (if not outright bloodshed).

Rain is a man set apart from his environment, almost completely detached from the well-oiled jailhouse ecosystem that churns around him. Save for interactions with his next-cell neighbor RC Stiles (played by an enthusiastic if overwrought Richard Lawson) and the conniving, jive-talking leader of the white supremacists (a scene-chewing Brian Dennehy), Rain keeps almost entirely to himself— as he likes to tell the prison bureaucracy, he belongs here and is concerned with doing only his time “and no one else’s’”.

His cell is undecorated and spartan, reduced to the barest of essentials (not unlike Neil McCauley’s spartan beachside condo in HEAT). He lives his life unaffiliated — free of the distracting prison politics that govern the various ethnic gangs — all the better to maintain a singular focus on running.

With a discipline that borders on religious devotion, Rain sprints laps around the yard’s track on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis. Soon enough, he catches the attention of a coach who invites him to train for an Olympic bid.

The initially-reluctant Rain allows himself the luxury of ambition and begins training with an eye towards a key qualifying trial, necessitating the building of a new Olympic-grade track inside the prison so as to accommodate his physical inability to leave the facility.

Facing the distinct challenge of making an unapologetic murderer admirable — heroic, even — Mann turns Rain’s bid into a bigger story of one man’s defiance against the system (and the casual cruelty of civilized society), inspiring a fractured community of convicts to come together for something bigger than themselves.

As Mann’s career has unfolded, he’s cultivated a reputation as a stylist concerned with aesthetic over substance. Mann’s style — slick, dexterous, moody — is most definitely conspicuous, but it’s misguided to suggest that oceans of subtext aren’t churning underneath the mise-en-scene.

Indeed, Mann reportedly hates the word “style”, and refuses to talk about his influences or compare himself to other directors. Author F.X. Feeney offers a description more suitable to Mann’s intent, calling him a “synthesist”: an artist who “immerses himself so thoroughly in his subject, throwing away whatever rings false, breaking truth down to its working parts”.

This conceit can certainly be applied to THE JERICHO MILE, a debut that finds Mann injecting significant aesthetic consideration into a TV movie format that conventionally holds little use for it. Like Feeney suggests, Mann and cinematographer Rexford Metz strip the 1.33:1 35mm film image of pretense, opting for clean, unfussy compositions and a functional approach to coverage that pack the maximum amount of narrative and thematic detail into each frame.

When the camera isn’t locked-off for a static composition, Mann and Rexford utilize considered dolly movements and zoom lenses that imply the director’s preference for visual precision. His experience in documentary realism is brought to bear in the film’s opening credits, which (in addition to indulging in Mann’s affection for graffiti and street art) deploys a long lens to observe the wider scope of inmate activity on the yard before finding Rain, wordlessly establishing his place within the prison’s social ecosystem.

What little flourish Mann does allow comes in the form of slow-motion shots reserved for the running sequences, allowing the audience to witness every ripple of Rain’s ultra-lean muscles with an almost-anthropological gaze while also suggesting that the act of sprinting brings a kind of mental liberation for Rain— as if he might be a majestic bird soaring high above it all, if only for a mile at a time.

Art Director Stephen Myles Berger complements Rexford’s utilitarian photography with a spare color palette that deals in stone tones that reinforce the high concrete walls surrounding the facility, while bursts of primary reds and blues echo the gangland politics and divisions that govern the inmates’ lives.

Beyond establishing Mann’s signature cold color palette and his unique brand of warrior-monk protagonists, THE JERICHO MILE transcends its disposable Movie-Of-The-Week roots due to its director’s all-consuming pursuit of authenticity and relentless approach to research.

The time he spent inside Folsom conducting research for his previous failed project supplied Mann with a treasure trove of material to draw from, all of which builds to a keenly-observed portrait of contemporary incarceration that the vast majority of prison narratives ignore in favor of more-salacious brutality like makeshift weapons and “dropped soap” episodes.

THE JERICHO MILE’s key achievement in this regard is Mann’s depiction of Folsom’s distinct ecosystem— a veritable self-sustaining city that exists within its walls. Cut off from the world they once knew, the inmates must build their own world, and have done so with remarkable detail: they have their own distinct social castes, yes, but they also have their own language & slang, their own trading economy, infrastructure, and industry.

They even have their own newspaper. Characters seem to come and go from their cells as they please, having achieved an uneasy, powder-keg peace with the guards and administration officials who allow this insulated world to continue unchecked in the name of rehabilitation.

Mann continually carves further detail into this surprisingly-complex ecosystem so as to emphasize just how far removed Rain has chosen to place himself from it— and subsequently, how his defiance of authority can rally a divided populace against the system designed to contain them.

Indeed, in an environment where affiliation can mean the difference between life and death, the man who stands alone might just be the most dangerous force of all. In the end, the TV movie format would prove unable to contain Mann’s larger theatrical ambitions.

Case in point: a rock-flavored score that bears more than just a passing resemblance to The Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy For The Devil” is symptomatic of a general refusal to let budget constraints diminish his canvas. Mann’s work evidently felt “theatrical” enough to warrant a release in European cinemas— a not-entirely surprising development considering the continent’s reputation for artistic hospitality.

This is not to say THE JERICHO MILE wasn’t appreciated domestically: it would go on to win two Emmys for Best Actor and Best Screenplay, as well as an award for Best Direction Of A Feature Made For TV from the Director’s Guild of America.

While Mann’s moody visual style wasn’t yet present, THE JERICHO MILE would nonetheless establish him as a filmmaker on the rise, imbued with a clarity of vision, an understated confidence, and an eye for evocative detail.

One could make a strong argument that THE JERICHO MILE’s exhibition on television has been more effective for Mann’s long-term career success than a conventional theatrical debut. Unbeholden to the industry pressures of box office performance and requiring very little effort on the part of audiences to actually watch it, the artistry of Mann’s emerging voice could be appreciated on its own merits— and on a much wider scale.

The success of THE JERICHO MILE would reportedly attract over two dozen job offers, but Mann’s aforementioned clarity of vision was already dictating what his next step would be: like his stubborn but principled convict protagonist, Mann was a man set apart… beholden to no one’s interest but his own.

He turned down every offer that came in to focus on blazing his own trail. In the process, he would forge a bold new future— not just for himself, but also for the very art of the moving image itself.

Author Cameron Beyl is the creator of The Directors Series and an award-winning filmmaker of narrative features, shorts, and music videos. His work has screened at numerous film festivals and museums, in addition to being featured on tastemaking online media platforms like Vice Creators Project, Slate, Popular Mechanics and Indiewire. To see more of Cameron’s work – go to directorsseries.net.

THE DIRECTORS SERIES is an educational collection of video and text essays by filmmaker Cameron Beyl exploring the works of contemporary and classic film directors. ——>Watch the Directors Series Here <———