RIVER OF GRASS (1994)

As a filmmaker born and raised in Portland, Oregon, I naturally feel a kinship to its homegrown film scene— one that’s been infused from the start by a freewheeling DIY spirit. The first ten years of my active filmmaking life were spent on reckless, ragged guerrilla shoots with close friends and like-minded artists, inspired by the dogged independence of such local cinema luminaries as Gus Van Sant or Todd Haynes as well as the rugged eccentricity of Portland itself.

Far from the watchful eyes of “The Industry”, we were truly free to make our shoestring epics and weirdo passion pieces. In the years since moving to LA, however, I’ve had to watch from afar as that eccentric hipster independence — the sort that fueled the bumper sticker mantra “Keep Portland Weird” — was co-opted, commodified, and trivialized by local-adjacents, if not outright outsiders.

Shows like “PORTLANDIA” and now “SHRILL” would use Portland as a backdrop to satirize the broader hipster culture that pervaded other, larger communities like Austin or Brooklyn, but in the process, would also conflate the Rose City itself with a patronizing, cartoonish you reductive character that utterly negates the vibrant spectrum of humanity that actually inhabits the Willamette Valley.

This cultural identity crisis isn’t unique to Portland, of course— it’s been happening in nearly every mid-tier American city for the past decade or more as a side effect of many other intertwining factors like the sharing economy, the exploding tech sector, gentrification, and rising income inequality. There are many other stories to tell about Stumptown beyond those of its white millennial creative class.

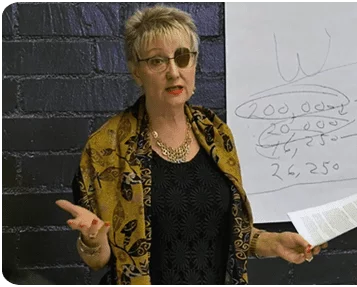

Thankfully, there are still a few filmmakers who wish to tell them— the irony of ironies being that one of the most authentically “Portland” voices is something of an outsider herself. Her filmography has since moved beyond the region’s confines, but director Kelly Reichardt has managed to carve out a formidable body of work that draws its primary inspiration from both Portland and the Pacific Northwest.

Her vision of Oregon cuts through the asinine clatter of fixey bikes, mustaches and mason jars to uncover a rich valley of human tragedy and drama, populated by stunted middle-aged friends, hardscrabble loners, wary pioneers, and conflicted eco-terrorists. She remains steadfastly independent, primarily supporting herself not through the influence and resources of Hollywood, but through her career as a teacher and artist-in-residence at Bard College in New York.

While only one of her to-date seven features has been able to crack the $1 million mark at the box office (2016’s CERTAIN WOMEN), Reichardt has nevertheless emerged as a major figure in American independent cinema– the figurehead of a resurgent minimalist movement that critic AO Scott has dubbed “Neo-Neo Realism”.

Beyond our shared cinematic affinity for the Pacific Northwest, Reichardt is also a director whose social orbit is closest to my own– one of my best and oldest friends counts her as a personal family friend, having worked with her on the shoot for MEEK’s CUTOFF (2010).

If I had an editor, I’d undoubtedly be told to cut the preceding two paragraphs because, admittedly, this is all a lot of indulgent grandstanding about Portland for an article that is actually about Florida. Oregon may be Reichardt’s adopted home, but her cinematic portraits of what Indiewire critic Eric Kohn has described as “characters trapped between the mythology of working-class American greatness and the personal limitations that govern their drab realities” , first reflected in her debut feature RIVER OF GRASS (1994), are informed by her upbringing in the Miami-Dade region.

Born in 1964, Reichardt fell in love with filmmaking via an interest in photography, which she cultivated first as a young girl on through to an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

In tackling her first feature, Reichardt drew inspiration from the geography of a childhood spent on the dividing line between Dade and Broward Counties: the exurban highways, ramshackle houses, rundown motels, and seedy bodegas that dot the Florida Everglades– dubbed by Marjory Stoneman Douglas as a “River of Grass” (and thus giving the film its title).

Working with producer Jesse Hartman, Reichardt subsequently devised a Gen X riff on Terrence Malick’s BADLANDS (1976); an anti-genre story in which a pair of would-be criminals attempt to go on the lam only to find they’re already trapped in a prison of economic circumstance.

Cozy (Lisa Donaldson) is a disaffected, lonely housewife in her 30’s with absolutely nothing going on in her life beyond her absent husband and young children. Fed up with her loss of personal freedom, she simply walks out of her house one night and winds up at a local dive bar across town, where she meets an aimless townie named Lee Ray Harold (played by associate producer and editor, Larry Fessenden).

Their booze-soaked flirtation, driven out of boredom rather than a genuine connection, leads to an impromptu midnight swim at his “friend’s” house, where he shows her the revolver his buddy found on the side of the road (not realizing the gun actually belongs to her father Jimmy Ryder, played by Dick Russell as an incompetent detective more interested in his yellow suits and drum sets than actual police work).

When they’re startled by the pool’s owner coming out to investigate the strange activity in his backyard in the middle of the night, they instinctively fire the gun and take off into the night before they can examine whatever damage they’ve done. Assuming they are now bonafide murderers, Cozy and Lee decide they have to flee Florida and forget their old lives. There’s just one problem– they’re short on cash.

RIVER OF GRASS subsequently follows their increasing disillusionment with their newfound fugitive status, as Lee’s inability to generate enough cash to even pay the daily rent for their motel room prevents them from leaving the immediate neighborhood of the supposed crime scene. Meanwhile, Jimmy Ryder commences the search for his missing daughter– an investigation that quickly reveals that Cozy and Lee are hardly the cold-blooded killers they think themselves to be.

Reichardt and cinematographer Jim Denault shoot RIVER OF GRASS with an unadorned, scrappy look befitting both its subject matter and its truly-independent production. While Reichardt’s later work employs a minimalistic, 16mm celluloid approach for aesthetic reasons, RIVER OF GRASS does so out of sheer necessity.

Strapped for cash like her onscreen protagonists, Reichardt opts for functional, observational setups designed for the square 1.33:1 frame. Her camera rarely deviates from a locked-off point of view, save for the occasional handheld shot or traveling landscape captured from a moving car. The hard brightness of the Floridian sun washes out most of the image’s color palette, save for the azure pop of the Atlantic ocean, the cloudless skies, or Fessenden’s t-shirt.

In her commentary for RIVER OF GRASS’ recent Oscilloscope home video release, Reichardt claims (or jokes) that she shot the film on a 1:1 shooting ratio– that is, nearly everything that was shot made it into the finished product. Low shooting ratios were once common among budget-conscious independent directors to looking to stretch paltry film stock budgets, but a 1:1 ratio for a commercially-distributed feature is virtually unheard of.

Regardless of the veracity of Reichardt’s claim, Fessenden nevertheless was able to quickly and easily assemble the film when it came time to don his editing hat. He and Reichardt borrow liberally from Malick’s aforementioned BADLANDS to shape RIVER OF GRASS’ narrative structure, right down to the usage of a disaffected and somewhat-rambling voiceover as a framing device and lingering close-ups on wildlife.

That said, the film steers clear of overt carbon copy, using its similarities to instead highlight the differences between the two films– the searing tar of exurban Florida is a world removed from the organic beauty of BADLANDS’ pastoral surroundings, and while the characters of Lee and Kit are both aimless losers, Lee’s on another level entirely: pushing 30, insufferably lazy, and living rent-free out of a spare room in his grandmother’s house.

RIVER OF GRASS’ distinctive approach to music also stands in stark contrast to the childlike wonder embodied in BADLANDS, driven by percussive snare drums diegetically performed by Dick Russell in-character as well as cheap rock and jazz muzak one might expect to find in a royalty-free music library from the era.

These bland, lifeless needle drops may seem a weird choice on their face, but in retrospect manage to reinforce the colloquial reputation of the narrative’s swampy Floridian surroundings as “God’s Waiting Room”– a flat landscape populated by people far past their prime, utterly bereft of genuine culture, passion or inspiration.

In such a male-dominated profession, it’s all too easy to make the mistake of confining a female filmmaker to her femininity; to assume she is incapable of telling stories outside of her inherently-feminine worldview. Reichardt’s artistry proves why such assumptions are so misguided and unfounded.

While she certainly doesn’t shy away from womanhood as a major theme in her work — indeed, RIVER OF GRASS pivots on the idea of a woman undergoing an identity crisis, abruptly rebelling against expectations of her as both a wife and mother — Reichardt resists reductive attempts to box her in as a strictly “feminist filmmaker”.

Rather, she’s more interested in glimpses of what she describes as “people passing through” (6): drifters, loners, and outcasts relegated to the margins of society, trapped in a restless search for a better life. As such, Reichardt is able to illuminate distinct aspects of the American experience that studio movies rarely portray.

Despite its casual slacker vibe, RIVER OF GRASS manages to paint a vivid portrait of working-class Americana that’s further shaded by the cultural nuances of the Gulf region. We see Cozy fill up her baby’s bottle— not with milk, but with Coca-Cola.

The seedy motel, which in most lovers-on-the-lam pictures serves as a temporary hideout, becomes a kind of prison for Cozy and Lee; their daily need to scrounge up enough cash to pay for the room entraps them in the very same neighborhood as the scene of the “crime”.

When they do manage to hit the open road, bound for New York City, they quickly find that they don’t even have enough cash to pay the freeway toll— and what’s more, they make the demoralizing discovery that they lack the criminal conviction to blow past it. The realization leads not to an explosive finale like we’ve come to expect from films of this type, but the rapid fizzling out of their criminal partnership.

This speaks to another trait that’s emerged through Reichardt’s subsequent work, wherein her narratives avoid conventional, tidy endings. The Guardian’s Xan Brooks perhaps puts it best when he writes that Reichardt’s films tend to “dissolve rather than resolve” (6). Her open-ended conclusions reinforce the narrow time window in which we are allowed to watch these protagonists, while alluding to the larger life they live beyond the confines of the screen.

RIVER OF GRASS had the extremely good fortune of being made during a boom time for homegrown independent cinema. Whereas the film might have struggled to get seen had it been made today, the higher barrier to entry in a pre-digital cinematic landscape allowed for the film to receive greater exposure at prestigious festivals like Berlin and Sundance, where it was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize.

Reichardt and company’s success on the festival circuit was followed by three Independent Spirit Award nominations, fueled by a limited theatrical release just large enough for RIVER OF GRASS to cement itself as an idiosyncratic cult film in the minds of adventurous cinephiles.

Reichardt had also managed to assert herself as the rare female voice in a male-dominated industry; a counterweight to the swinging machismo of 90’s indie cinema, embodied in films like RESERVOIR DOGS (1992) and SWINGERS (1996).

Despite her ascendant artistic profile, it would be quite some time before Reichardt could parlay that into another project— a regrettable development that’s since been rectified several times over, and yet prompts speculation as to whether the film’s modest success might’ve gained more traction had Reichardt been a man.

Indeed, for the bulk of its aftermarket lifespan, RIVER OF GRASS has stood as something of a lost artifact of 90’s indie cinema, relegated to a poor DVD transfer from an obscure boutique label. Thankfully, Reichardt’s continued success in recent years would provide an opportunity to revisit her debut.

Oscilloscope Films, the home video distributor for later Reichardt works like WENDY AND LUCY and MEEK’S CUTOFF, would procure the rights to RIVER OF GRASS and harness the director’s small but passionate fan base to crowdfund a brand-new 2K restoration in 2015.

While the result isn’t quite exactly pristine or sparkling— nor could it could ever be, considering its shoestring budget 16mm origins — we now have a clear, vivid, and lovingly-preserved iteration of the idiosyncratic debut that launched one of the most important voices in contemporary independent cinema.

ODE (1999)

Director Kelly Reichardt released her debut feature, RIVER OF GRASS, in 1994, but her sophomore effort, OLD JOY, wouldn’t arrive until 2006. At the risk of stating the obvious, that’s a gap of twelve years — an unnaturally long period by any standard of measure.

While such developments are rare among most commercially-successful filmmakers, they are frustratingly common amongst a certain subset of directors regardless of success: women. A recent example can be found in Debra Granik, who won top honors at Sundance with WINTER’S BONE in 2010, but is only just now releasing her follow-up (LEAVE NO TRACE).

One could also look to Patty Jenkins, who has only recently re-emerged to prominence with 2017’s WONDER WOMAN after debuting in 2003 with MONSTER. Five years into this undoubtedly frustrating period, Reichardt decided to take matters into her own hands.

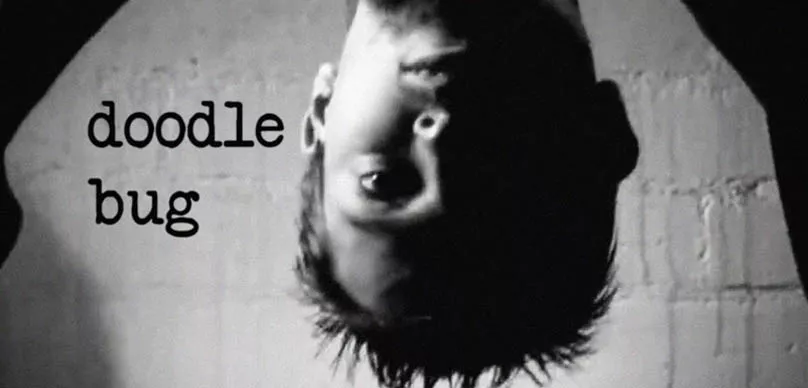

The plan to combat her career stall would begin with the making of three short films. The first of these, 1999’s ODE, would be more ambitious than the rest in its scope, clocking in at a runtime of 50 minutes. By most industry metrics, a 50-minute runtime technically constitutes the dividing line between the short and feature formats— as such, there are conflicting reports as to whether OLD JOY or ODE stands as Reichardt’s true second feature.

It all depends on one’s personal standing. We count it as such, if only because its artistic ambitions reaches so clearly above her other shorter works from this period. Produced under her RIVER OF GRASS collaborator Larry Fessenden’s Glass Eye Pix banner, in partnership with Susan A. Stover (who also recorded sound on-set), ODE finds Reichardt adapting Herman Raucher’s 1976 novel “Ode To Billie Joe”.

Reichardt’s screenplay updates the setting from 1976 to present-day, which only highlights the insularity and conservative regressiveness of the story’s wooded Mississippi town. Bobbie Lee (Heather Gottlieb) is an innocent, devout Baptist girl whose burgeoning womanhood is causing her to chafe against the strict expectations of her community.

The simmering interior tension comes to a head when she meets Billy Joe (Kevin Poole), a brooding young townie who wears a mask of casual nonconformity to hide his confusion about his own sexuality. The two begin meeting underneath a local bridge, slowly building a relationship beyond the watchful eyes of the town.

Their fumbling attempt to consummate their love comes comes crashing down when Billy Joe reveals that he’s unable to perform, having become wracked with guilt over a recent romantic encounter with another boy. What results is a tragic meditation on the pressures of conforming to one’s environment, and the roiling anguish that can ensue when a sense of self-identity is thrown into sudden flux.

Befitting its shoestring budget status, Reichardt executes ODE with a crew of two— co-producer Stover running sound, as mentioned before, and herself working as the cinematographer. It’s notable that ODE is shot on Super 8mm film, especially when considering that Reichardt could quite easily have shot with prosumer digital cameras.

By 1999, such cameras were widely available, even if the ability to capture crisp footage at 24 frames a second was not. The choice to shoot on Super 8, then, implies itself as one made purely for aesthetics. Indeed, Reichardt has yet to shoot a project with digital cameras, pointing to a personal preference for celluloid that sets her apart from her peers in the independent realm.

More than anything, ODE asserts itself as a transitional work in Reichardt’s artistic development, bearing traces of RIVER OF GRASS’ slight stylization while laying the groundwork for the rugged, lived-in realism that would mark all of her subsequent features.

Her unadorned, observational camerawork uses natural light to imprint a sunny, autumnal aura onto the frame, its colors already smeared into slight abstraction by virtue of the smaller, amateur/enthusiast film gauge. Camera movement is limited to maneuvers that a crew of one can feasibly pull off— handheld setups, rack zooms, and the usage of a car as an impromptu dolly.

Editor Philip Harrison helps Reichardt retain some of the BADLANDS influence that was so deeply felt throughout RIVER OF GRASS, notably through the spotty, inconsistent deployment of ruminative voiceovers from both Bobbie Lee as well as an omniscient third-person narrator, in addition to frequent close-up cutaways to surrounding wildlife.

Folk musician Will Oldham arguably stands as ODE’s most notable collaborator, providing an original score comprised of a wistful, lilting guitar tune that reinforces the film’s Appalachian backdrop while establishing the foundation for a creative partnership that would later translate to a starring role for Oldham in Reichardt’s next feature, OLD JOY.

Despite its obscurity and estrangement within Reichardt’s official canon, ODE nevertheless complements her core artistic and thematic priorities. Its low-key meditation on the challenge of reconciling the spectrum of romantic orientation within a hardline community dovetails neatly with Reichardt’s ongoing examination of people who live on the rural fringes of society, trapped within a cultural narrative they’ve no longer come to fit.

It doesn’t necessarily add to Reichardt’s filmography as a whole, but it still holds interest for those looking for a more-complete picture of her creative worldview. Perhaps more crucially, ODE’s true import arguably lies in its kickstarting of Reichardt’s momentum after a sustained fallow period — a development that undoubtedly compelled the burgeoning director to double down on her independent inclinations, thus setting a firm trajectory for the subsequent course of her career.

Those wishing to see the curio that is ODE either have to wait for the rare repertory theater screening, or contend with the embedded rip from a VHS tape above (with German subtitles, interestingly enough). With any luck, a faithful restoration of the original Super 8mm film elements could help the film community recognize ODE’s transformational place in Reichardt’s broader career.

OLD JOY (2006)

The Portland I knew growing up is gone now. Its soggy, homegrown eccentricity has long since been replaced by a cosmopolitan renaissance. A ruggedly provincial, semi-blue-collar character has given way to a creative class comprised of outsiders and economic refugees fleeing the runaway cost of living in larger cities like LA or San Francisco.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does raise important questions about what it means to undergo such a rapid character shift at a citywide level— and what we stand to lose. Films like Gus Van Santa’s MY OWN PRIVATE IDAHO (1991) or books like Chuck Palahniuk’s “Fugitives and Refugees” capture the Portland of old: a grunge paradise of misfits, dropouts, and yuppies with the hook-up to the Nike employee store.

Now that character is conveyed to the outside world through reductive parodies like PORTLANDIA or fundamentally-misperceived portraits like SHRILL. One could imagine there’s an abundance of DIY homegrown films by Portland filmmakers that accurately capture its character as it stands today, but therein lies the inherent irony: to authentically capture Portland’s genuine character is to embrace underground obscurity.

There is, at the very least, one film that manages to both boast a national profile in addition to genuinely capturing Portland’s slacker spirit: Kelly Reichardt’s 2006 feature, OLD JOY. The picture that began Reichardt’s long cinematic love affair with Portland and the greater Oregon region, OLD JOY also marks the beginning of her ascent as a figurehead of contemporary independent filmmaking.

One of the quieter films in recent memory, Reichardt’s third (some would say second) feature eschews the theatrics of active plotting in favor of passive observation. To describe it on it a surface level, it is essentially a story about two friends who take to the woods in search of a hot bath, where the emotional conflict is buried so deep into subtle nuances of characterization that a friendly massage becomes the de facto narrative climax.

Such descriptions, however, do a massive disservice to the aching beauty and contemplative serenity of OLD JOY, which Reichardt co-adapted from a short story by Portland-based author Jonathan Raymond. Having first been exposed to Raymond’s work by reading his novel “The Half Life” on a road trip, Reichardt discovered that they shared many of the same narrative and thematic interests (1).

She subsequently approached him to see if he had any short stories she could adapt to screen— specifically any that took place mostly outdoors (1). This ask would seem to follow the template she established with 1999’s ODE, which also was adapted from pre-existing literature and took place in outdoor locations that could be secured on the cheap.

Reichardt and Raymond’s subsequent writing collaboration, however, would prove more fruitful than either could have expected, establishing a symbiotic creative partnership that would run through no less than three consecutive projects.

Reichardt had embarked on projects since ODE (the little-seen, enigmatic short THEN A YEAR (2001)), but the production of OLD JOY represents a substantial leap forward in the development of her artistic voice.

The film boasts some serious producing cred, with Portland-based indie mogul Neil Kopp working in partnership with Anish Savjani, Jay Van Hoy, and executive producer Todd Haynes (who, along with Gus Van Sant, stands as both one of the figureheads of queer cinema and a founding father of Portland’s filmmaking scene).

That said, OLD JOY avoids the type of polished “produced” vibe that such talents might engender, opting for a lived-in earthiness that speaks to the city’s rugged DIY spirit. Reichardt manages to flesh out the barest sketch of a story — carefree nomad / functioning hobo Kurt (Will Oldham) invites old friend Mark (Daniel London) to accompany him on a trek to the Bagby Hot Springs in Estacada to reconnect with nature and rekindle their stagnating friendship — transforming what is essentially a minimalist character study into a timeless, melancholy story about the inexorable passage of time and its effects on friendship.

The meaning of the film’s title is revealed through the course of the climactic hot springs sequence, as Kurt details a dream in which he received a profound emotional truth from a wise stranger: “sorrow is nothing but worn out joy”.

An oblique truth, but a truth nonetheless— this “old joy” might be alternatively described as nostalgia, whereby happy memories become infused with the melancholy knowledge that they can’t be easily recaptured. Mark and Kurt are very much caught up in this state of mind, their long-time friendship on the verge of a major paradigm shift as Mark’s impending fatherhood and Kurt’s refusal to be tied down lead to a fundamental incompatibility.

This sense of the inevitable — the way that time transforms the nature of our various relationships, and the sobering realization that some friends don’t make the leap into new phases of life with you — permeates OLD JOY, creating a mournful aura that begs to be quietly observed in a ritualistic manner.

Rather than hold a wake for their friendship, Mark and Kurt opt to suspend it within an almost banal moment of time; a simple, non-assuming “see you soon” implying that the very opposite stands as to the likeliest of scenarios.

The production of ODE proved that Reichardt could shoot a film with only herself, a sound person, and actors. OLD JOY builds on this minimalist conceit by adding only one additional crew member, despite enjoying access to far more resources than her previous projects.

In fact, Reichardt designs the production so that the entire company could feasibly fit within Mark’s station wagon— London and Oldham in the front, Reichardt, sound man Gabriel Fleming and cinematographer Peter Sillen in the back, and her dog Lucy in the trunk (1).

It may not be the most comfortable way to make a film, but this extremely intimate approach boasts immediate benefits in her actors’ quietly soulful performances as well as the film’s earthy, naturalistic aesthetic. While this scenario is now fairly common amongst digital films made by the microbudget faction of the indie world, one has to consider the additional challenge of doing so with bulky film equipment.

Reichardt is unique among the celluloid-friendly filmmakers of her generation in that she prefers the organic grit of Super 16mm to the industry-standard 35mm gauge. OLD JOY builds upon this filmic foundation established by RIVER OF GRASS, adopting a 1.66:1 aspect ratio with which to frame observational set-ups captured via a locked-off tripod, subtle handheld setups, and even from the backseat of a moving car.

This fleet-rootedness further empowers Sillen and Reichardt’s use of available light to render Oregon’s signature color palette: the clay brown of its forested floor, the blue-green canopy of Douglas fir trees, and the soggy grey skies that hang low overhead. Reichardt once again serves as her own editor, populating her ruminative footage with evocative cutaways to surrounding wildlife, much like she had done in her previous work.

And yet, the lack of a voiceover conceit moves OLD JOY firmly away from the BADLANDS influence felt throughout RIVER OF GRASS or ODE, and towards the silent, unblinking gaze that would come to define her own aesthetic.

Yo La Tengo’s spare, contemplative score cements this transition; having previously had one of their own songs licensed for ODE, the celebrated indie rock band now gets to actively shape OLD JOY’s musical landscape with new compositions comprised of noodling guitar plucks and wistful piano chords.

The result is a folksy, ruminative music bed that matches both the interior theatrics of the story as well as Reichardt’s emergence as a mature filmmaker who exhibits her confidence through restraint and quiet nuance.

OLD JOY’s role in the definition of Reichardt’s artistic character is more of a technical or aesthetic one than it is thematic. The feminine character perspective that shapes the majority of her work is mostly absent here, save for the brief moment we get to spend alone with Mark’s frustrated and very pregnant wife at the beginning of the film.

Said moment, however, stands as a sly commentary on Reichardt’s part about the exclusionary nature of the film’s narrative archetype. Stories about venturing into the wilderness to find oneself tend to almost exclusively favor the masculine perspective— the womenfolk must stay home and tend to the babies, after all.

The opening scene goes to great lengths to establish that Mark’s wife feels very strongly that he doesn’t need her permission to go out and do things, as if the very act of his asking implies she is a “naggy” wife who wishes to keep him entrapped within the pillow-lined cage of domesticity.

Nevertheless, Reichardt leaves her character alone in the kitchen as Mark hits the road, forced by her pregnancy to conform to gender roles and suppress her own personal ambitions. To their credit, Mark and Kurt do fit somewhat within Reichardt’s artistic interest in characters that live on the fringes of mainstream society— both lack the exterior strength or virility one would expect in a masculine protagonist taking to the woods.

Indeed, they would very easily be supporting characters in someone else’s story. This in and of itself makes OLD JOY worth making: the story becomes an oblique entrypoint into a cinematic study of male friendships that we don’t often see on screen, colored by all the complexity that aging and growing emotional distance entails.

OLD JOY also makes an interesting — albeit characteristically-subtle — comment on the very idea of being “one with nature”. There is a pervasive sense in our culture that the natural world holds the secret to our truest selves… we just have to venture out and find it.

Some opt for the path of least resistance and let “nature” come to them: they meditate in overly-curated miniature gardens like Mark is seen doing at the beginning, or, like Mark’s wife does, they make a vitamin-rich smoothie out of bitter greens as if it were the elixir to perpetual health and vitality.

OLD JOY suggests that these commercialized forms of “holistic” living are ultimately hollow; true self-discovery isn’t about manufacturing a scenario in which it can happen. Rather, it is about simply listening to the world around you, letting its beauty and wisdom wash over you— like a long soak in a hot spring.

Despite a very limited theatrical engagement, OLD JOY managed to make quite an impression with critics, who appreciated its serene melancholy enough to reserve a spot for the film in their year-end Top 10 lists.

Doubtless, there were many negative reviews from many who simply neither understood or refused to open themselves up to its wistful wisdom, but time has effectively rendered their opinions moot— OLD JOY is almost universally regarded today as a beacon of homegrown filmmaking. More importantly, it would re-establish Reichardt’s creative voice after twelve years of relative silence, ushering in a prolific new period that would launch her towards the forefront of American independent cinema.

TRAVIS (2004)

Like many other artists of the time, the highly-controversial outbreak of the Iraq War weighed heavily on director Kelly Reichardt’s mind. Easily the most divisive conflict since Vietnam, the Iraq War was waged by the George W. Bush administration as a drastic pre-emptive measure based on faulty, misleading, and downright false intelligence.

As the years dragged on, and the quagmire claimed an ever-higher number of American soldiers, the artistic call to action grew more and more undeniable. When Reichardt heard hers, she was in the midst of a professional struggle; after making a splash at Sundance with her 1994 debut RIVER OF GRASS, she was now thrashing underwater, laboring to come up for air with a worthy follow-up.

Said follow up would ultimately arrive in 2006 in the form of OLD JOY, but in the interim she used this period of obscurity to experiment with form and technique.

After completing her 8mm featurette, ODE, in 1999, and the short project THEN A YEAR in 2001, Reichardt created TRAVIS (2004), an experimental meditation on grief as informed by war. The piece is less of a short narrative than it is a video installation one might encounter at a museum. Also shot on Super 8mm film, TRAVIS is set to droning, ambient music as a blurry sea of color lulls us into a serene, contemplative mood.

A short audio snippet of a woman talking enigmatically plays on a loop, giving us fragments of a vague story about some kind of personal tragedy. As the loop continues to repeat, Reichardt populates the soundtrack with more snippets of audio— as if filling in the missing pieces of this woman’s story.

All the while, the picture never strays from its soupy color show, although a fleeting glimpse of a boy’s arm poking out of a red t-shirt tells us we’ve been looking at something that’s been blown up to the point of abstraction. Without ever saying as much explicitly, the woman’s audio eventually reveals itself as a lament over the loss of her son, a soldier in the Iraq War.

TRAVIS is more consequential within the context of Reichardt’s filmography than it lets on, setting the stage for her career-long juxtaposition of hard, everyday reality against the romantic myths of working class Americana. This sect of the population produces the most soldiers by a wide mile, mostly because armed service immediately asserts itself as a viable alternative to a successful life when college is uncertain.

As such, we accord a kind of stoic dignity to soldiers and their families, commensurate with the grave sacrifice they’re asked to take on our behalf. We pay lip service to their courage in public forums, glossing over their unimaginable pain of loss with cheap platitudes and lionizing invocations of heroism. TRAVIS lays that raw pain bare, with the mother questioning the need for his sacrifice in the context of a controversial war with a flimsy justification.

This period of relatively obscure short-form works — comprised of ODE, THEN A YEAR and TRAVIS — nevertheless marks an important milestone in Reichardt’s artistic development: namely, the infusion of political subtext into her storytelling. Whereas other directors such as Oliver Stone or Michael Moore wear their politics on their sleeve, imposing it upon their subjects, Reichardt cedes her convictions to her characters, choosing stories that are colored by a specific political ambience but can still exist outside of them.

ODE and TRAVIS are more overt in this regard, what with the former’s meditation on homosexuality in an oppressively religious community and TRAVIS’ lamenting over Iraq. These, and other tenets of the conservative doctrine of the George W. Bush years, would go on to become core themes of Reichardt’s work, allowing her films to stand as both a firm (albeit quiet) rebuke to said policies as well as humanizing portraits of the people affected by them.

WENDY AND LUCY (2008)

When the Great Recession arrived in mid-2008, very few people outside of the financial sector saw it coming. Naturally, it was the middle and lower-class factions that bore the brunt of the damage, their jobs and life savings having evaporated away overnight while wealthy corporations received generous government bailouts.

Jobs, homes, and dreams were lost as the runaway economic progress of the Bush years revealed itself to be fundamentally hollow, propped up by a mountain of financial speculation made in bad faith. Despite losing my first job out of college before I could build up any savings, I was able to still weather the storm thanks to parents who were in a position to support me until I was back on my feet.

Most were not so lucky, faced with the sobering prospect of being the first American generation to be worse off than the one that came before it. Many learned a hard truth that the lower middle-class already knew quite well: poverty isn’t just an economic status, it’s a precarious state of being where a series of small inconveniences can trigger a full-stop catastrophe.

It’s often said that art reflects life— a sentiment that handily applies to director Kelly Reichardt’s WENDY AND LUCY, which dropped right into this uncertain economic atmosphere with its chilling reflection of our quiet calamities.

Based on Jonathan Raymond’s short story “Train Choir”, WENDY AND LUCY carries a surprising amount of dramatic weight on its delicate narrative frame, transforming a sketch about a drifter’s search for her lost dog into a resonant meditation on street-level capitalism and the social compacts that guide our lives.

Reichardt follows a similar template to the production of OLD JOY, shooting in Portland with executive producer Todd Haynes and Larry Fessenden’s Glass Eye Pix, in addition to her recurring collaboration with producers Neil Kopp and Anish Savjani.

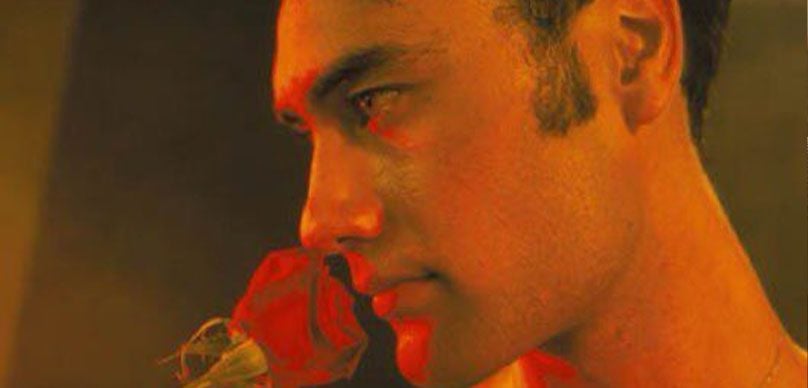

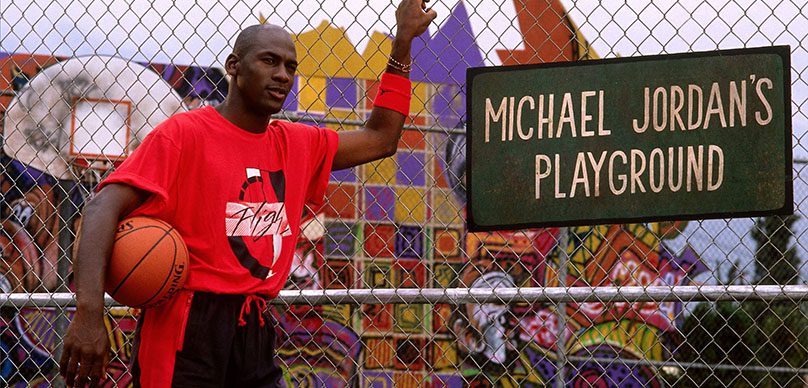

Nevertheless, WENDY AND LUCY’s production marks a substantial leap forward for Reichardt, boasting the support of additional production company Filmscience as well as a $200,000 budget that blows OLD JOY’s $30,000 endowment clear out of the water. While still a relatively paltry number in the context of even the most low-budget studio film, $200,000 nevertheless compounds Reichardt’s artistic cred to a degree where she’s able to cast her first “name” actor in Michelle Williams.

In the first of several subsequent performances throughout Reichardt’s filmography, Williams imbues the titular character of Wendy with a scrappy, desperate pathos and an androgynous appearance that serves to further highlight her marginalized position on society’s fringes.

A drifter from Indiana on her way to Alaska in hopes of work, Wendy hits a major roadblock in her journey somewhere on Portland’s outer fridges, where the city starts to bleed into the smaller surrounding towns. Her only companion is her dog, Lucy, played by Reichardt’s real-life pet of the same name (and all-around good girl).

Together, they make the best of a bad situation after Wendy’s beater of a sedan suddenly dies on her, effectively stranding them in an unfamiliar land with a meager supply of cash that dwindles by the hour. In giving the entirety of herself over to Reichardt’s vision — to the point that she even slept in her character’s car as part of her preparation — Williams delivers an authentic, well-worn performance that pulls its nuance from her grief over the sudden death of her partner, Heath Ledger earlier that year (1).

With her grungy cut-off shorts, unassuming blue hoodie and boyish dark haircut, Williams is practically unrecognizable, to the point that bystanders would completely ignore her when they came up to talk to the crew (1). She bears the burden of carrying the entire film on her shoulders, as the story is told so singularly from her point of view that we never leave it.

Supporting characters serve as avatars for the various ways in which people either help or hurt a stranger in need. Will Oldham’s hipster nomad or Will Patton’s cold-but-fair mechanic showcase a pragmatic empathy while still keeping Wendy at arm’s distance.

John Robinson, who we haven’t seen much of since his breakout performance in Gus Van Sant’s ELEPHANT (2002), uses his character as an aggressive bagboy who busts Wendy shoplifting to display our easy tendency to dehumanize strangers, especially when they can be viewed to belong to a lower economic class than us (it’s no accident that a huge cross dangles from his neck… an ironic sigil of his distinctly un-Christian lack of compassion).

Fessenden cameos in WENDY AND LUCY’s scariest sequence: a genuinely terrifying encounter in which Wendy camps out in the woods only to wake up with a menacing man standing over her and delivering a profanity-laced monologue. His character represents the gravest danger of Wendy’s situation: the unpredictable and hostile forces that share her marginalization.

Beyond her trusty Lucy, Wendy’s only friend in this intimidating new place is Wally Dalton’s security guard, a kindly, paternal man who should be sitting on a porch somewhere in blissful retirement, but must stand on his feet all day guarding the parking lot of an exurban Walgreens. Despite a contentious first encounter, he becomes an unlikely beacon of comfort for Wendy as her situation grows more dire; he’s always around to offer a helpful tip, or even slip her a little cash like he does at the end of the film.

The fact that it’s only five or six dollars speaks volumes about his own empty wallet; he pushes the cash on Wendy with a gentle force that implies this gift is not to be taken lightly because it’s a lot of money to him.

With OLD JOY, Reichardt debuted a formal — albeit minimalist — aesthetic, one whose seeds were evident in RIVER OF GRASS but took many years to take root, let alone blossom. WENDY AND LUCY builds upon that foundation, perfecting the earthy, organic look that has come to define her subsequent work.

Working for the first time with cinematographer Sam Levy, Reichardt shoots the picture on Super 16mm film to create a soft & grainy realism. A preference for natural light gives WENDY AND LUCY a warm, sunny aura that runs counter to the dim grey that blankets Portland’s skies ten months out of the year.

It’s a very different story at night, where bastard-amber streetlamps and flickering fluorescent tubes smear Wendy’s surroundings into a lurid industrial nightmarescape. Reichardt and Levy frequently opt for locking off their 1.85:1 compositions, creating an observational aesthetic that’s amplified by placing various abstractions in the foreground of the shot.

The effect is furtive, or inconspicuous; like watching something we’re not supposed to see. Dolly-based tracking shots or handheld moves are reserved for key moments, making their arrival all the more impactful and underscoring Wendy’s increasing desperation. Reichardt once again serves as her own editor, opting for the patient, contemplative pace that marked OLD JOY.

Interestingly, Reichardt as editor takes the opportunity of WENDY AND LUCY to make a drastic adjustment to one of her artistic signatures, using frequent closeup cutaways to the surrounding environment— but not to highlight the beauty of nature, as her previous films did. Instead, these shots of train tracks, intimidating freeways, and sprawling parking lots suggest the oppressiveness of industry when experienced at eye level.

WENDY AND LUCY also eschews her previous work’s use for music, save for an uneasy tune that Wendy frequently hums to herself throughout. By abstaining from a conventional overscore, Reichardt reinforces the harrowing realism of her approach with a natural dramatic urgency.

By not instructing her audience how to feel about Wendy’s journey through musical prompts, Reichardt manages to capture our genuine sympathies and concern, stoking further reflection on our own sense of responsibility towards our fellow person— stranger or otherwise.

WENDY AND LUCY resonates as one of Reichardt’s best works precisely because of its harmony with the director’s artistic and narrative interests. Wendy is the archetypical Reichardt protagonist: a life lived on the fringes of mainstream society, marginalized by her environment. She belongs to the working poor, perhaps one of the most invisible castes in American society.

She straddles the razor-thin line between lower-middle-class comfort and outright homelessness, tracking every single penny that comes in or goes out while she sleeps in an old car that’s one engine light away from the scrap heap. And yet, one wouldn’t know it to look at her— she could easily pass as just another young person happily playing with her dog in the park.

Her economic invisibility cloak is precisely why she’s stuck in a dangerous position, her independence undermined by a sudden reliance on the kindness of strangers. Lucy is her only tether to society, keeping her grounded and visible. Once that’s gone, she’s a ghost— and ghosts can be easily ignored.

The downward trajectory of Wendy’s journey strikes to the core theme in Reichardt’s work to date: the constant clash between the everyday realities of blue-collar, working-class Americana and the romantic aura of gritty, up-by-your-bootstraps, frontier-trailblazing myth frequently ascribed to them (often at their own peril).

Reichardt’s characters find themselves under immense pressure to conform to this narrative, which has always been a false, impossible one spun less by their own kind and more by patronizing politicians who have no further use for them after their votes have been counted and the election night confetti has been swept away.

WENDY AND LUCY stands as a quiet, yet forceful comment to two aspects of this broken myth, the first being that stubborn old chestnut that says America is a land of endless opportunity where one can always reinvent oneself in another town or city. However, real life bears out a pathetic irony: those most in need of self-reinvention are often the least able to relocate or escape.

The only thing that pushes Wendy through a series of mounting economic misfortunes is the promise of plentiful work in Alaska. This, of course, is it’s own unique myth— the golden glow of a faraway promised land waiting to receive economic refugees as a reward for the harrowing journey they must undertake to get there.

This is the foundational promise of America itself, fueling immigrants across endless oceans or covered wagon convoys across bone-dry deserts. Naturally, these people found a whole new set of problems when they finally arrived— and there’s no reason to believe anything else is waiting for Wendy up in Alaska. The second truth that Reichardt seeks to illuminate lies in Dalton’s kindly security guard character.

He’s of the hearty, working-class stock one might expect to see watching over a Walgreen’s parking lot, but thanks to his age, he’s certainly in no shape to chase after any shoplifters.

Reichardt’s decision to cast the character as a grandfatherly benefactor allows Wendy a brief respite from the ambient hostility of her situation, but his presence as such implies a darker socioeconomic truth: runaway inequality has made retirement and financial security increasingly more uncertain for the middle class, even if they’ve been steadily working for decades.

With its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, WENDY AND LUCY marks Reichardt’s entrance onto the world stage as a filmmaker of international renown. The film’s warm reception earned Reichardt a nomination for the Un Certain Regard award, while Lucy won the festival’s unofficial fan-favorite prize, the Palm Dog.

Thanks to a smart distribution strategy on the part of Oscilloscope, WENDY AND LUCY sustained that golden Cannes glow through its theatrical run, earning near-universal praise from critics and Independent Spirit Award nominations for Best Feature and Best Female Lead. Crucially, the film also saw healthy financial success at the box office— no small feat considering its limited engagement at scattered arthouse theaters.

A worldwide gross of $1.1 million — against a production budget of $200,000 — would not only make a powerful statement about the benefits of economic, back-to-basics filmmaking, but it would also prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that Reichardt had a sizable, active audience following her work.

So many new filmmakers deliver brilliant, promising films, only to fizzle out because their audience was too small to sustain, but the success with WENDY AND LUCY virtually eliminated that problem for Reichardt. It had taken fourteen years, but Reichardt finally achieved a platform for herself upon which to grow her career in the direction she deemed fit.

This is hard enough to do as a man in the studio world, let alone a woman in the independent one— and she did it without caving to style trends or adapting a property with a built-in audience. Simply put, Reichardt’s success is 100% hers; a testament to her DIY fortitude as well as an inspiration to countless up-and-coming filmmakers looking to blaze their own trails.

MEEK’S CUTOFF (2010)

The Oregon Trail holds a venerated place in the annals of American myth, buoyed by a pioneering spirit as well as its status as a cultural touchstone for every Millennial who played the iconic computer game. The actual journey, however, was far from some game or romantic adventure— it was a grueling, sluggish trek across an endless expanse of desert prairie broken up only by a treacherous mountain pass.

The hostility of the terrain was matched by the conflict they encountered with the various native populations that inhabited it— a conflagration fueled by the settlers’ deep mistrust and contempt for an alien culture they did not understand. The voyage was one filled with hard choices, where the moral standards of civilization could easily be sacrificed to the needs of survival.

Despite its relatively high historical profile, there are surprisingly few films about the Oregon Trail, and even fewer that capture the gritty uncertainty of the pioneers who made the trek. Director Kelly Reichardt’s MEEK’S CUTOFF (2010) asserts itself, then, as the definitive film chronicling this fascinating chapter of American history.

The piece is at once a return as well as a departure for Reichardt: a return to Oregon, to the subversion of genre that informed RIVER OF GRASS (1994), and to the fruitful collaborations with executive producer Todd Haynes, writer Jon Raymond and producers Neil Kopp & Anish Savjani that resulted in both OLD JOY (2006) and WENDY AND LUCY (2008).

Beyond just the change in scenery, its departures take the form of additional producers Elizabeth Cuthrell & David Urrutia and its central conceit as a period piece— Reichardt’s first.

As a story set during the last, harrowing leg of the Oregon Trail in 1845, MEEK’S CUTOFF was always going to deal in the visual and narrative grammar of the Western, but Raymond’s script muddies the black-and-white clarity of the genre’s entrenched moral code with the grey shades of a simmering thriller.

A caravan of covered wagons faithfully follows their feral guide, Stephen Meek, across the arid eastern Oregon desert. Played by a nearly-unrecognizable Bruce Greenwood, Meek’s wild mountain man appearance and raconteur affectations inspire a wary confidence that he is the right man to lead these homesteaders into the promised land of the fertile Willamette Valley.

The journey goes roughly as well as could be expected, until they capture a lone native who’s been silently tracking them. Played by Rod Rondeaux as a stoic prisoner who betrays no emotion about his sudden captivity, The Indian (as he’s called in the credits) splits the fragile unity of the wagon party right down the middle; some believe he’s secretly communicating with his tribe and inviting an ambush, while others find themselves growing distrustful of Meek’s increasingly-prejudiced judgment.

Michelle Williams, in her second consecutive performance under Reichardt, leads this insurgent faction as the pragmatic, observant Emily Tetherow. As the group’s paranoia escalates, Emily asserts herself as the cooler head that must prevail, lest the bickering and infighting between the men cloud their sense of reason (a standout moment finds Emily stitching The Indian’s moccasin back together for him— but not out of the goodness of her heart, but because she wants him “to owe her something” should he unexpectedly gain the upper hand).

This central conflict allows an opportunity for nuanced performances from other members of the wagon party; most notably from Paul Dano and Zoe Kazan as a younger pioneer couple prone to anxiety, and WENDY AND LUCY’s Will Patton as Emily’s husband.

Typical of Reichardt’s narrative inclinations, MEEK’S CUTOFF eschews the grand theatrics of physical conflict in favor of the compelling subtleties of characterization; the simmering tensions don’t build to a resolution in the conventional sense, but rather serve as an avenue for Reichardt and company to explore the psychological wear and tear that can result from the friction between an extreme scenario and our most basic human impulses.

MEEK’S CUTOFF’s “anti-western” approach extends beyond its narrative framework, encapsulating the whole of its aesthetic design and execution. Reichardt’s starting point is the aspect ratio, which eschews the widescreen vistas typical of the genre for a confining 1.33:1 Academy frame.

When asked about this decision in press interviews, she has stated she chose this narrower aspect ratio to evoke “the view from inside a bonnet”, eliminating our peripheral vision while dropping us directly into the story’s feminine perspective. The effect is an appropriately claustrophobic one, made all the more remarkable by virtue of the story taking place entirely outdoors.

MEEK’S CUTOFF also finds Reichard upgrading from 16mm to 35mm film, with the higher gauge giving eastern Oregon’s dry desert scrub and gentle slopes a striking clarity. Cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt proves instrumental in the evolution of Reichardt’s aesthetic, retaining her preference for natural light and minimalistic camerawork while boosting contrast levels for a moodier look.

Their use of available light — the unrelenting blast of high-noon sun, or the dim glow of magic hour — takes on a kind of hostile beauty, as if the wagon train has ventured into a forbidden realm. Reichardt and Blauvelt take an even-bolder approach come nightfall, choosing to render said sequences almost entirely in blackness save for the practical light of a campfire or the use of a single china ball lantern to simulate the wan glow of the moon.

It’s a very tricky prospect to deprive the audience of a picture — the fundamental building block of the medium — for an extended period of time, but the effect as executed here ably communicates the suffocating blackness of night in the desert. It also forces us as the audience to lean in close to listen to the fervent whispering between these would-be pioneers as they try to make sense of a shaky situation.

MEEK’S CUTOFF anchors its recreation of the Oregon Trail outside of Burns— a small town of just under 3,000 people that butts up against the Burns Paiute Indian Reservation. Gone are the lush forests of the Willamette Valley to the west; this is a very different rendition of Oregon, albeit one more in line with the state’s geographical majority.

The sparsely-populated setting provides a somewhat-colorless backdrop — various shades of brown against gradient skies — but production designer David Doernberg leans into the challenge with an authentic historical recreation that’s as imaginative as it is realistic.

The caravan of covered wagons reads true to the mythos of the period, if only slightly smaller than what we tend to imagine. The monochromatic backdrop affords Doernberg and costume designer Vicki Farrell to use color to striking effect, most notably in the dresses worn by the pioneer women.

The boldly-colored garments feel almost obscene; a needlessly-extravagant luxury in the face of such a hostile and barren environment. In the wide, they almost resemble exotic birds who have inadvertently flown too far away from another world. This refusal to yield their femininity in the face of the elements speaks to Reichardt’s artistic embrace of grit and stoicism as character traits not exclusive to men— a conceit that also manifests via the director’s longtime practice of performing editing duties herself.

One could argue that she gets away with her minimalistic approach to coverage because she has direct foreknowledge of how it will be assembled in the edit. As such, Reichardt’s editing sensibilities often echo the observational, patient nature of her characters and camerawork.

Considering MEEK’S CUTOFF’s spare deployment of dolly or handheld setups in favor of locked-off compositions, the edit naturally takes on a plodding, yet determined, pace that reinforces the long, grueling journey onscreen. A mysterious, ambient score by composer Jeff Grace turns the desert into an experiential abstraction; the settlers might as well be traversing the surface of Mars.

With his work on MEEK’s CUTOFF, Grace joins Reichardt’s roster of close collaborators, his having come to her attention likely due to his work for the films of fellow Larry Fessenden / Glass Eye Pix acolyte, Ti West.

If OLD JOY and WENDY AND LUCY established the core conceits of Reichardt’s thematic agenda, then MEEK’S CUTOFF reinforces them with a narrative that touches on those key tenets. Reichardt’s films are inextricably tied to her feminine, left-of-center perspective— even in OLD JOY, where the two male leads subvert the masculine trope of “venturing into the wilderness” in favor of a soulful and sensitive reconnection.

In this regard, Williams’ character of Emily Tetherow provides a compelling window through which to observe the story as MEEK’S CUTOFF unfolds. Already marginalized by dint of her womanhood in a time where women had no place in seats of power, Emily is forced to stand on the sidelines and watch as the caravan’s menfolk let their vanity and ego overpower their grip on an increasingly-tense situation.

She possesses the fortitude and grit required of a pioneer— much more so than Meek, even — but yet she can’t rise above the restrictions of her gender until the social compact breaks down entirely. While she’s ultimately victorious in asserting herself and bringing the conflict back from the brink of chaos, her win is a small one: she simply replaces her husband’s vote when he’s incapacitated.

The production of MEEK’S CUTOFF also affords Reichardt the opportunity to deconstruct the romantic myth of The Oregon Trail in a fashion similar to her sobering depictions of America’s working class in previous work. The “frontier myth” is a potent narrative that drives our cultural character, especially in the West; after all, what could be more American than the idea of pulling up your bootstraps and forging the life you want for yourself in a plentiful landscape?

It’s easy, then, to forget what had to happen in order to make such a dream possible in the first place— the uprooting and decimation of an entire civilization that had already called that land “home” for centuries. Beyond simply reminding us that the journey westward was far from the glamorous or romantic adventure that the Anglo-Saxon view of history makes it out to be, MEEK’S CUTOFF uses its spare narrative to challenge the supposed “righteousness” of Manifest Destiny.

The pioneers were told that it was their moral duty to expand the American experiment across the continent, giving them a deluded justification to invade foreign lands with total disregard for the locals. In this context, MEEK’S CUTOFF gains a timely resonance despite its period trappings, drawing a firm line from the philosophies behind Manifest Destiny and the uniquely American brand of imperialism that drew us into a “pre-emptive” war with Iraq.

Reichardt makes this connection very subtly, refusing concrete allusions in favor of allowing the audience to organically infer and absorb MEEK’S CUTOFF’s political sentiments. By stripping the romantic glow of myth from her narrative, Reichardt reveals how small these figures actually are— dwarfed by a landscape that never needed them to begin with.

That Reichardt made MEEK’S CUTOFF in 2010 when the Obama Administration was laboring to roll back the damage of the Bush Doctrine only reinforces her message; much like how the pioneers had ventured too far to turn back and go home, our haste to bring “democracy” to a distant, oil-rich land had entrapped us in an inextricable quagmire.

MEEK’S CUTOFF premiered at the 67th Venice Film Festival before going on to a limited theatrical engagement typical of its indie status. While the film’s slow, deliberate pace may have turned off those looking for more of a rousing experience typical of the western genre, many critics responded to it with appreciation and admiration.

Beyond her artistic expansion into a historical period outside of the present, Reichardt has also diversified her cinematic portrait of Oregon from the Willamette Valley to include its vast eastern deserts, adding another entry into what has become a comprehensive chronicle of the Beaver State’s varied cultural geography and complicated history.

With her three Oregon-set films, Reichardt had done the heavy lifting necessary to restore her creative momentum after a long period of stagnation– and with their success on the international stage, she had empowered herself with the freedom to manifest her own destiny as a trail-blazing pioneer of rugged, soulful filmmaking.

NIGHT MOVES (2013)

The state of Oregon boasts a long and proud history of eco-activism, be it as simple as routine composting and recycling at the individual level or as sweeping as governmental efforts aimed at preserving our natural resources. The beauty of nature knows no politics; our lush forests and bubbling streams of fresh mountain water inspire conservative and liberal alike to maintain the sanctity of our environment.

Of course, any movement or cause is going to have its fringe fanatics— extremists who refuse to recognize nuance (and sometimes even reason) into the conversation, committing themselves to the politicization of issues that we all should theoretically be able to agree on. In this time of runaway climate crisis, they might argue, the cost of inaction is too high to ignore. Desperate times call for desperate measures.

This sentiment has given rise to a movement of renegade eco-activists; fringe militants who actively desire (and attempt) to sabotage our energy infrastructure in the name of a cleaner planet. Their mission, however, is something of a paradox— to be a responsible steward of nature is to care for all the living things supported by it.

Blowing up a dam to restore natural water flows isn’t necessarily evil, per se, but it does cause a criminal amount of damage and could put the local population in danger. It also doesn’t make a good look for other environmentalists trying to enact change through legitimate means.

Nevertheless, the psychology behind such a character that can claim absolute righteousness within such a slim grey area of morality makes for compelling drama. It is precisely this scenario that director Kelly Reichardt explores in her fifth major feature, NIGHT MOVES (2013).

Written by her scripting partner Jonathan Raymond, the film is structured as a simmering thriller about unintended consequences and the emotional fallout from a deed you can’t undo. In many ways, NIGHT MOVES represents the most “conventional” film of Reichardt’s career, diving further headlong into subversive genre storytelling after the success of her anti-western MEEK’S CUTOFF in 2010.

The end result, funnily enough, loses some of the resonance of Reichardt’s particular artistry in its reach towards a more-commercial profile.

That said, NIGHT MOVES nevertheless finds Reichardt spin an idiosyncratic and effective yarn about the compounding effects of guilt and desperation. Set in the southern part of Oregon around the town of Ashland, the story concerns Jesse Eisenberg’s Josh: a quiet, pensive and slightly-schlubby eco-activist who is about as far off the grid as one can get in the modern era.

He lives in a little yurt on an agricultural commune, along with a group of other like-minded people that includes Alia Shawkat and Katherine Waterston in very minor roles. Whereas his fellow commune dwellers have more harmonious dreams for a sustainable lifestyle, Josh harbors grander —if not more destructive — ambitions. He links up with an ex-Marine named Harmon, played by Peter Sarsgaard with a deceptiveness masked by his laidback charisma.

Harmon shares Josh’s dream for radical action, and has the know-how to build a bomb with available materials; he just needs Josh’s help in procuring the raw materials for an explosive and a boat to use as the delivery device. With the help of Dakota Fanning’s Dena — an emotionally fragile young woman who compensates with a wry sense of humor — Josh purchases a small boat from a clueless rich suburbanite and begins converting it to a floating bomb.

The mission is successful enough; the trio are able to blow up a dam under cover of night and evade the police. For all their best laid plans, however, they fail to account for the human factor. The explosion causes a flood, which is their expected result, but it also claims the life of an innocent person camped downstream.

The merry little band of eco-terrorists instantly fractures when the news breaks, causing a crisis of grief and guilt that slowly builds to an unexpected conclusion that asks a complicated question: how far would you go to save the earth, and how much farther would you go to cover it up?

On a technical/craft level, NIGHT MOVES asserts itself as a transitional work in Reichardt’s career. Creative continuity is retained through her recurring partnership with executive producers Todd Haynes & Larry Fessenden and producers Neil Kopp & Anish Savjani. A handful of additional producers — Saemi Kim, Chris Maybach, and Rodrigo Teixiera — quietly complement Kopp and Savjani’s work, fashioning NIGHT MOVES as a comparatively slick (but not over-produced) film within Reichardt’s otherwise rough-hewn filmography.

NIGHT MOVES’ big aesthetic departure lies within its digital cinematography, marking the first time that Reichardt has worked with the format. The film was shot in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio on an Arri Alexa camera, but she and returning cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt manage to avoid the sterile flatness that tends to plague digitally-acquired films.

The look of NIGHT MOVES is decidedly earthy, employing what appears to be a post-added film grain effect to create a soft, pleasing image that approaches the organic warmth of celluloid. Reichardt and Blauvelt harness the diffuse, soggy light of the Oregon cloud layer to capture a naturalistic and autumnal color palette. A combination of locked-off static compositions and deliberate dolly movements create an observational, minimalistic tone on par with Reichardt’s previous work.

Reichardt once again performs her own editing duties, creating a simmering slow burn that’s reinforced by returning composer Jeff Grace’s brooding score, which mixes ambient electronic textures with guitar and piano to evoke the haunting rural environment and Josh’s inner grappling with his moral decay.

For all its affectations of “commerciality” or mainstream appeal, NIGHT MOVES nevertheless doggedly refuses to abandon Reichardt’s artistic principles. Her thematic fascinations continue to inform the perspective of her storytelling, with NIGHT MOVES serving as an opportunity to convey her worldview to a much wider audience.

In a filmography populated by people existing along the margins of society, NIGHT MOVES presents a particularly interesting subculture— those who actively choose to detach themselves from the modern world’s infrastructural grid. Josh, his fellow conspirators, and his friends at the agricultural commune have chosen to sacrifice a life of creature comforts and convenience in the name of environmental purity and sustainability.

It’s an extreme view, admittedly, but it’s also one that’s surprisingly common throughout Oregon and the greater Pacific Northwest region. As admirable as it is to lead a sustainable life and reduce your carbon footprint as much as possible, it’s also impossible to adhere to with 100% success without some degree of delusion.

Just because Josh and the commune live outside of industrial society doesn’t mean they have escaped it entirely— they still rely on industry for essentials like clothing and, I’m assuming, water & power. This means they must participate in the mainstream economy, which means they need money, which means, at the very least, they must sell their harvest at local farmer’s markets.

To do this, they must transport these goods to and from the farm via gasoline-guzzling pickup trucks. They are caught in a feedback loop whereby their efforts to combat pollution must actively contribute to it. They have to turn to ever more-drastic measures if they wish to break the loop, embracing ideas and principles that align closer to violent extremism than the harmonious pacifism they pay lip service to.

The film’s message, then, is quite clear: the individual cannot simply live by a righteous environmental purity in this day & age. The industrial revolution has created a force that’s too powerful and too pervasive; total abstention is impossible. Reichardt hammers home this sentiment with the film’s ambiguous, open-ended conclusion, whereby Josh attempts to evade suspicion by dropping right back into the grid he despises.

Forced from the commune that had been his social and economic cocoon, and with nowhere else to turn, Josh applies for a retail job at a local outdoor supply chain. The final shot speaks to Reichardt’s minimalist sensibilities, using a static closeup of a relatively mundane image — a ceiling mirror reflecting a woman texting on her cell phone — to convey his ultimate imprisonment within the consumer-surveillance state; he may or may not get away with his horrible acts, but he’ll always be looking over his shoulder.

He’s learned that the myth of the valiant ecological crusader is simply that— a myth. The reality is far more sobering & uncertain, leaving him further marginalized as he compromises his principles in exchange for his freedom.

NIGHT MOVES premiered to a warm reception at the Venice Film Festival, and even took home the Grand Prix award at France’s Deauville Film Festival— an increasingly-vital event for doggedly independent international cinema. Reichardt’s play at larger, more-conventional audiences stateside wasn’t quite as successful as its festival campaign, failing to crack $300k at the domestic box office despite positive critical notices.

This is not to say that NIGHT MOVES is a failure, however— its distinct appeal as a crossover work more than justifies its existence, and the budget was likely low enough that any losses were comparatively minimal. More importantly, the film stands (for the time being) as the last panel in Reichardt’s complex cinematic portrait of Oregon and the sympathetic freaks and fringe folk who call it home.

One of the very few filmmakers to understand that the state is much more geographically diverse and historically-complicated than the heavily-white, progressively-minded hipster utopia of its largest city, Reichardt has managed to weave a comprehensive, deeply-humanist tetralogy of stories that are uniquely and singularly Oregonian.

Having traveled to the Rose City to visit Todd Haynes during the tail end of a major creative slump in the early 2000’s, she found the fertile Willamette Valley to be a promised land of artistic reinvigoration and limitless potential— utterly free from the industrial constraints or intimidating business expectations of distant epicenters like LA or New York.

Her subsequent immersion in its creative community established her as a pioneer of contemporary American independent cinema, and a key voice in charting the course towards new frontiers.

CERTAIN WOMEN (2016)

As an ideological or sociological construct, The West looms large over the American psyche. Far more than a physical, geographical region, it has come to represent a state of being that embodies our foundational values: freedom, fortitude, and persistence.

Ever since the film industry dropped into California to escape Thomas Edison’s tyrannical enforcement of his cinematograph patent, this mythical land of cowboys, natives, and pioneers has figured prominently within the medium of cinema. While we’ve long regarded The West as a place of reinvention where one can build a better life, the economic policies of the late twentieth century have made that dream all but impossible for most.

The creeping isolation of our social media-obsessed, hyper-connected lifestyles has compounded this new reality, creating a paradox in which endless open skies become suffocating ceilings, pushing relentlessly downward onto the horizon.

Director Kelly Reichardt understands the self-defeating consequences of our national attachment to pioneer myths, bringing her cutting insights and quiet compassion to bear on a handful of features about regular folks marginalized by their own environment. Until presently, the stage of play had been the soggy forests and arid desert scrub of Oregon, the destination point of our westward expansion.

Over the course of four films — OLD JOY (2006), WENDY AND LUCY (2008), MEEK’S CUTOFF (2010) and NIGHT MOVES (2013) — Reichardt has drilled down into the fallacies of the Western narrative, exploring the emotional and psychological fallout that occurs when destiny fails to manifest; when the political interests of the elite few subvert the well-being of the honest, hard-working masses who wish to simply keep to themselves as they pursue their own modest vision of life, liberty & happiness.

Oregon may be a large state, but it’s not so large as to sustain a lifetime’s worth of creative exploration. Indeed, after the completion of NIGHT MOVES, Reichardt felt that she had sufficiently “shot out” the Beaver State, and began looking towards alternate vistas as the backdrop for fresh inspiration and a rededication to aesthetic minimalism.

Reichardt would find this fresh backdrop in the state of Montana— more specifically, in the vision of Montana as rendered in the prose of author Maile Meloy. Until this point, Reichardt and Portland-based novelist Jonathan Raymond had been inseparable collaborators, but Meloy’s ruggedly delicate voice seemed to suggest that Raymond wasn’t the only one plugged into Reichard’s artistic interests.

After reading Meloy’s various collections of short stories, Reichardt found herself drawn to three in particular, and began the tricky process of adapting them to screen without the benefit of a writing partner (perhaps in deference to her relationship with Raymond).

The end result — 2016’s CERTAIN WOMEN — would mark a dramatic leap forward in her artistic development, subsequently revitalizing her position at the forefront of American independent cinema with a soft-spoken, yet incisive, triptych about the sociological fallout that still lingers a century after the closing of the frontier.

The quaint small town of Livingston serves as something of the capital of CERTAIN WOMEN’s emotional geography; it is a hub that connects the disparate narrative strands, if only through psychological means rather than physical. Like many small cities in rural America, the fundamental makeup of Livingston’s character is changing, having undergone a cultural renaissance as the creative class and families alike remake it to better resemble the hip urban centers whose high cost of living they fled to escape.

One might call it gentrification, although the displacement occurring here is — for now, anyway — mostly existential. CERTAIN WOMEN cuts a wide swath through this setting to arrive at a cross-section of its distinct economic classes. Rich, poor, or everything in-between, it seems nobody is spared by the ennui that occurs when modernity intrudes on a community otherwise removed from time.

The film’s first section features Laura Dern as Laura, an aggrieved Livingston lawyer battling the below-grade misogyny of a client who doesn’t accept her evaluation regarding the merits of his workplace injury case until he hears it from a male consultant.

Jared Harris plays Fuller, the said client, as emblematic of the perceived victimhood of the rural white working class, masking his inability or unwillingness to adapt to a world he no longer recognizes with a stubborn, unbending, and exclusionary pride. Harris’ sense of victimhood stems what he views as a bureaucratic injustice perpetrated by uncaring corporate interests, even though the insurance papers he signed clearly state that he forfeits his right to sue for additional damages the moment he accepts his workman’s comp.

His world now in shambles, Fuller lashes out with the only action he feels will finally make him heard: breaking into his former employer’s office with a rifle and holding a security guard as his hostage. It falls to Laura to enter the building and defuse the situation, leading to a moment of wounded understanding between two exhausted people, worn out by swimming upstream all their lives.

Dern‘s lived-in performance brings it home, emerging in Fuller’s eyes as the lone voice of reason in a world gone mad. Her wary empathy speaks to the profound truth behind this vignette: we dismiss the maladies of the working class at our own peril— not just because they might seek refuge in desperate, violent acts, but also because the cancers of late capitalism will inevitably metastasize to consume the middle class, too.

CERTAIN WOMEN’s second story finds Reichardt once again collaborating with Michelle Williams, who had previously delivered indelible performances for the director in WENDY AND LUCY and MEEK’S CUTOFF. Williams’ Gina is cut from an entirely different cloth from those characters, illustrating the particular travails of Montana’s privileged class.

She, her rebellious teenage daughter, and her husband, Ryan (James Le Gros), seem to live an idyllic life of rustic comfort; they’re currently building their dream home, and on the weekends they voluntarily choose to “rough it” in a surprisingly-lavish tent on the land they’ve bought, complete with a television and a queen bed frame.

Of course, money can’t buy happiness, and each spouse has their own secret coping mechanism— cigarettes for Gina, an affair in the city with Dern’s character for Ryan. In a narrative conceit so wispy and interior it would barely even qualify as “narrative” to most audiences, Gina attempts to sort out her ennui by fixating on a pile of sandstone that an elderly neighbor has accumulated on his front lawn.

This isn’t any old sandstone, however— this is authentic sandstone from pioneer days, and nothing less will do when it comes to the materials that will make up their new dream home. The neighbor ultimately agrees to give it to her, but not without initially exhibiting some resistance.

This instills a twinge of guilt on Gina’s part, making for a hollow victory that forces her, if only for a brief moment, to consider the emotional costs of her crusade for material perfection. There’s not enough sandstone in Montana to imbue her marriage with the same authenticity she seeks for her home.