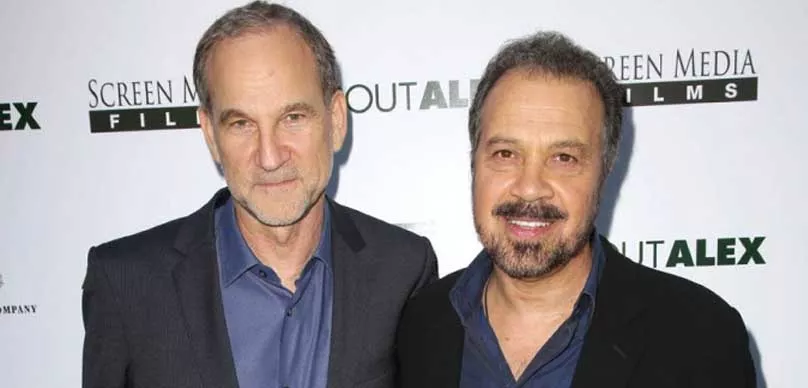

Our guest today is producer, director and screenwriter Marshall Herskovitz. Many of his production projects have been in partnership with his long-time filmmaking collaborator, Edward Zwick whose films, he’s produced and written half of. Their decades-long filmmaking partnership was launched as co-creators of the 1987 TV show, ThirtySomething.

Now, Marshall had already written for the TV show, Family, in 1976. So his understanding of TV was pivotal in the success of ThirtySomething.

Other projects he’s credited for executive producing or creating include Traffic (2000), The Last Samurai (2003), Nashville (TV show 2016), Blood Diamond, and Women Walks Ahead(2017), starring the incomparable, Jessica Chastain.

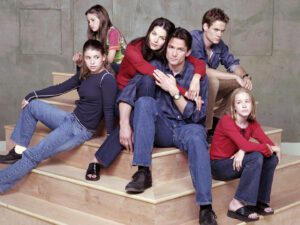

Marshall show, ThirtySomething, which only ran for four-season was quite successful. Co-created with Zwick, the follows the stories and journeys of seven thirtysomethings living in Philadelphia who struggle with everyday adult angst.

The show’s success earned over a dozen Primetime Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and personal honors for Marshall from the Writers Guild and a Directors Guild.

Herskovitz’s filmography is pretty adventurous. We discussed as many as we could in this interview and he was totally down for the ride. But if we are to highlight some must-mentions, Traffic will get the spot. Herskovitz co-produced Traffic in 2000 alongside esteem producer, Laura Bickford and directed by Zwick.

The film holds a constant 93% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and won numerous Oscars BAFTA, Screen Actors Guild, and Golden Globes awards in 2001. It followed through grossing a total of $207.5 million on its $46 million budget

The President appoints a conservative judge to spearhead America’s escalating war against drugs, only to discover that his teenage daughter is a crack addict. Two DEA agents protect an informant. A jailed drug baron’s wife attempts to carry on the family business.

Another classic of his is the 1999 TV show, Once and Again. A divorced father and a soon-to-be-divorced mother meet and begin a romantic courtship which is always complicated by their respective children and their own life problems.

Marshall dropped all sorts of knowledge bombs on the tribe this week. You have to listen to the episode to hear all those extra deets he shared with us about the attempts at rebooting ThirtySomething and many more.

Enjoy this conversation with Marshall Herskovitz.

Alex Ferrari 0:05

I like to welcome to the show, Marshall herskovits How you doing Marshall?

Marshall Herskovitz 0:10

I am. Well, how are you?

Alex Ferrari 0:12

I'm doing well, my friend. Thank you so much for doing the show. I'm a fan of of many of your films, including the films that you've just written and produced, but directed as well. And we'll get into that in the future. But I, I heard nothing but good things from you from Ed, who was on the show as well. Edward Zwick, and, and I said, Well, I kind of get Marshall on the show, too. I can't just talk to Ed, I want to talk to Marshall as well. It's so thank you so much for doing this. I appreciate it.

Marshall Herskovitz 0:40

Well, I'm happy to do it. And just know if I say anything that Ed said. Yes. stole it from me.

Alex Ferrari 0:47

Fair. Fair enough. Fair enough. Okay, give me one second. Hold on a second. technology's acting up. So give me one second. You're

Marshall Herskovitz 1:00

just like your room there.

Alex Ferrari 1:03

Thank you. I worked hard on it. I give my wife the excuse that it's for business. That's how, and I always tell. I always tell people that the Yoda was a is a pre pre wife purchase is definitely a pre wife purchase. To say the least because it's a hard it's I have kids now. And it would be it'd be it. I can't have that conversation. I know the kids need money for school, but I need a life size Yoda. I get it. Alright, so. So before we get started, Marshall, how did you get into business?

Marshall Herskovitz 1:50

Well, you know, it's funny. I went to Brandeis back in the early 70s, which dates me severely. And I majored in English. In fact, I majored in Old English, I was very interested in medieval England. I was a Tolkien freak, and just loved sort of Beowulf and that whole kind of, you know, early medieval, epic poetry sort of thing. And at the same time, at that moment, for some reason, I can't explain. There was a huge interest in old movies. Like when I was living in Boston, there were two different revival movie theaters in Cambridge. And then on campus, one night a week, there was an old movie shown. So basically, I was watching three old movies a week. And when I look back on it, I realized that the real education I got in college was in movies. I just didn't know it at the time. And I fell in love with movies, I fell in love with classic movies. And by the time I was a senior in college, I wanted to be a filmmaker. And, and the odd thing is, all I wanted to do was make medieval epics. That's that was my goal, go to Hollywood and make medieval epics. And here I am, 40 years later, and I haven't made one. But, you know, there's still hope, at any rate, that is what propelled me into the film business. I graduated, I made a short film, which was not a medieval epic, it was a very intimate, you know, drama. And I, I came out to Hollywood, thinking that that would be my ticket to fame and success. And I literally could not get one person to even look at it. It was that was the most disheartening. And in those days, all you had was the Yellow Pages, I went through the Yellow Pages for all production companies, and called every single one in Los Angeles, and no one would look at it. So after about six months of floundering, I heard about this amazing film school called American Film Institute. And I thought, well, maybe I should do that instead. And so that's, that's where I went. That's where I met ad on the first day. And, and really, that gave me my start, really, and you guys just just, you know, school, school chumps who got together and then and just

Alex Ferrari 4:05

stuck together for the last 40 years working on projects together. That's amazing. That's

Marshall Herskovitz 4:09

right. That's right. We're the longest living partnership in Hollywood right now.

Alex Ferrari 4:13

Really? That's actually saying a lot actually.

Marshall Herskovitz 4:16

Yeah, actually is no, I told me I'm very proud of and, and I know he is, too, and we have worked independently all along, but nevertheless, our preferences to do things together.

Alex Ferrari 4:29

Yeah, absolutely. I, I had a similar education when I but I didn't, I had a video store. I worked at a video store for a while. So I did the same thing. I'd watched three movies a night, you know, high school, so there's nothing else to do homework. So I would just, I would just take home movies and just watch and watch and I got such an education. And that was before I even wanted to become a director at the end. I was like, I guess I guess I kind of want to be a director kind of similar to you. So you wanted to make Excalibur but never did

Marshall Herskovitz 4:55

is what you say that's correct. Yes, yes,

Alex Ferrari 4:58

but there's still hope. There's Till hope,

Marshall Herskovitz 5:00

I finally after 30 years got to write a screenplay of the story of 1066, the Norman Conquest of England, which was something I had desperately wanted to do. And, you know, I still have hope that we'll make that as a movie. But you know, it's not exactly a moment now in the history of the film business when you can make big films like that. So

Alex Ferrari 5:21

we'll see. I mean, you put a cape on the main character, I think you have a better shot.

Marshall Herskovitz 5:28

I know that's the world, you know, with superpowers could these various people have? It's?

Alex Ferrari 5:33

No, is that is that is that a serious conversation that someone actually have a conversation with you about that?

Marshall Herskovitz 5:39

Not about that, but about something as ridiculous. Something I don't even want to go into. It just, it was a thing about Vietnam. And someone suggested that maybe if they had different superpowers, people might be more willing to look at a story about the Vietnam War. upsetting

Alex Ferrari 6:01

It was kind of it's kind of like when when they went in and pitched James Cameron Titanic to, you know, Jack's back like that a certain point, you just got to go. It's enough. It's enough. Now I have I have to ask, I was looking through your filmography. And I have to ask, what was it like work writing for chips. I mean, I'm a 70s. Kid. So I have to go right there, I went straight to it. I went straight to chips because I had the By the way, I had the pleasure of directing Erik Estrada, and some commercials years ago, and the stories Oh, my God, the stories he told about what happened in the 70s. People just don't understand what the 70s

Marshall Herskovitz 6:39

I understand. By the way, I never went near that set. So I have no stories to tell about the production of it. All I can say is that that was the low point of my career. I wish when I got out of film school, right, I spent about three or four years trying to be a freelance writer in episodic television, which is, by the way, doesn't really exist anymore. They don't really have people to make a career as freelance writers and television anymore. And, at one point, chips was the only job I could get. And I read one of their scripts. And it was like it was written in another language, I just had no idea how to do this thing. There was no connection there. Once he went to the next dialog didn't make sense, I literally was completely lost. And I came up with it with a sweet idea, actually, about an old Native American who thought his grandson was losing, you know, was not knowing enough about the old way. So he was raising his grandson in Griffith Park, away from people, you know, hidden away. Nice. And they bought it, they liked that do and it was Michael ansara, who played him, of course, because in those days, Michael and Sarah play Native Americans. And so it didn't turn out so bad. But for me, it was a very humiliating experience, because I had no idea. I just was not the type of thing I knew how to write. And in fact, that was part of what catalyzed, I think, the most, one of the most important moments in my career, which was a decision I made after three or four years of doing that, that I just was going to stop. In other words, I sat down and wrote a screenplay as a spec thing. And I wrote out the work the story together together. And then I wrote the screenplay. And I said to my wife, I said, you know, either this is going to work, or I'm leaving the business because I just cannot go on doing what I feel to be a bad job, doing other people's voices, meaning the voices of shows, you know, and and. And so that willingness, I think, to take that chance, and to say, I'm either going to make it on my terms, or I'm going to walk away. What's what turned everything around. And the interesting thing is that that screenplay that I wrote, had never been made. It was almost made three times. But it did change everything for me, because people were able to see my voice and I got work from it. And the work I got from it was what then gave me my career. So the willingness to bet on myself, was a scary thing at age 26, or 27. But that was that was what made it happen.

Alex Ferrari 9:31

I mean, that's pretty enlightened for a 26 or 27 year old, to be honest with us, God knows I was in much worse shape than you were at 26 or 27. I was lost. I was in the darkest pit of my time. That's a whole other story for another podcast. But um, but in most, most 20 year olds don't have that kind of reflection or that honesty, that kind of bravery. to just go, you know, I'm gonna make it on my end, and people listening. It's a very different industry than it was when you were doing this. It was less competition that it wasn't cool to be a screenwriter or director. It wasn't. Nobody even knew what that was to just knew that movies were made.

Marshall Herskovitz 10:08

Yeah, I know, it's true. I mean, it was hard to break in it, by the way, there were trade offs, because there was much fewer product. You know, there were three television networks in those days instead of 200. You know, it's easier to get a job today, but harder to have your own voice today. You know, I think you could have a voice in those days. And, and, and I felt that I had one. And it was something that I that I felt I needed to listen to. So you know, look, the one thing has always been true, which is to make it in this business, you have to be driven, you have to be, you have to need to do what I remember, when I was still in Boston, talking to some person who had been to Hollywood, you know, saying, you know, how do I do this? And, you know, do I have a chance of making it? And this person said to me, basically, if there's anything else you can do, you'll end up doing it? If there's nothing else you can do, then maybe we'll have a chance.

Alex Ferrari 11:15

I don't listen, I don't know if it happened to you. But I mean, I've gone through this, I mean, I've got a lot of shrapnel, I'm sure as you do in this battle of these years working in this business. And there was times I wanted to leave, I'd like I just I can't take it anymore. I want to quit. It's I'm like I and then the voice in the back of your head, like what else you're gonna do? What are you going to go and get real job? What does he get it like it's at a certain point you just like, and that happened to you multiple times? And how did you break through that? Because it's still happening?

Marshall Herskovitz 11:53

I have to say about that, I have to say about that. First of all, I had an inherent belief in what they now call the hero's journey before he had any idea of what a hero's journey was, it's so deeply embedded in our culture, that I believe that everything was a test. And, you know, they're going to throw the shit at you to try to get you to quit, and therefore you just have to try harder. Why I thought that I don't know, no one told me that. That was just my belief. And so my belief was Okay, I get it. Oh, now, six bad things have happened. And I want to leave. Okay, this is the moment when you have to dig down and say, No, I'm not going to leave. I don't know why I believe that. I'm grateful that I did. Because I think it got me through. But the other thing is, it took me many years to realize this something somebody Ed and I talk about a lot. There's a cycle in this business and probably other businesses, but I think it's more of this business, because it's so speculative. The cycle goes like this, you are nobody, you have nothing to lose, you do something bold, you do something original. people notice it, you get attention, you they start to build you up, you start to make money, people start to believe in you, you start to think that you know what you're doing. And in thinking that you know what you're doing, you become cautious, and, and maybe arrogant. And then you make a stupid mistake, and you come tumbling down and are completely humbled by the business. And in the midst of your despair, you have nothing to lose, and you could start being original again. And I could chart five times in our career, when that sort of thing has happened where in some way, you know how they say in Southern California, fire is a natural part of the lifecycle of this environment and it you need to have fires. Well, failure is a natural part of the lifecycle of a career. You have to have failure, you have to fail at things. That's the only way you learn. That's the only way you you grow and become better. And I think people are so afraid of failure, that they become mediocre to avoid it. And the business now allows for that, you know, you know, we always talk about how people fail upwards, which means they're mediocre and they don't make a huge mistake. So they sort of keep sort of moving up. I'm not a believer in that. I'm a believer in you take the chance and then you take what happens

Alex Ferrari 14:32

you know like I mean there's a filmmaker out right now who's you know, taking swings at the bat that I'm so regardless if you'd like the movies or not but someone like Chris Nolan who oh my god is taking massive swings at the Bat believable. Yeah, unbelievable swings at bat and I'm so glad there's guys like him and Fincher and these kind of guys that just go up there and just take massive because there's there's you could take Creative choices are creative challenges and do things that are original at a lower budget. But when you get up to the 150 to $100 million, and you do something like inception, or 10.

Marshall Herskovitz 15:10

I know

Alex Ferrari 15:11

that's, that's a that's a risk. Because imagine if that really badly, you could put in direct to jail. And that's the thing.

Marshall Herskovitz 15:20

I understand. And I have enormous respect. And as you say, it's like I couldn't even follow Tennant. You know, I'll be honest, I couldn't follow it. I want to watch it again. Watch it backwards, you know. And then he makes Dunkirk, which is like, sublime. Do you know what I mean? And it doesn't matter, because he's an incredible filmmaker, who has a vision, who has the resources, the wherewithal and the courage to follow that vision. And, and and you're right, we need people like that. We need a business that will still support people like that. And if there's one big difference between today and 3040 years ago, it's that there were more people in positions of power, who were willing to trust filmmakers back then. That's just a fact.

Alex Ferrari 16:08

I mean, look, we wouldn't have Star Wars. Without Alan Ladd I mean, Alan lamb took a risk on a filmmaker who made THX 1138, which was a horrible bomb. He's like, Hey, you know what? I think let's give him like 9 million sure you can have the merchandising rights. I'm sure that that will work out fine for everybody.

Marshall Herskovitz 16:28

You know, one of the most famous stories in Hollywood merchandising story was amazing. Well, because

Alex Ferrari 16:34

all contracts were rewritten after that. I mean, it would have for that

Marshall Herskovitz 16:37

totally.

Alex Ferrari 16:39

Because like there's no money in lunchboxes and our action figures. What is that to a sci fi movie at? You're taking kid? It's, it's absolutely remarkable. I always talk I always talk about the the punch that everybody gets in this in this business. No matter how big you are, no matter how accomplished minor were what stage in life you are. punches continues to come all the time. And as you get older, as you get older, you learn how to duck, a bit. Like when you're younger, you learn how to take it, you learn how to take the punch and keep going like you were saying like, okay, they threw six or seven things at me. Screw you, I'm still going. That's the taking of the punches. But some people get that first punch and their outfit out of the game. They're cold cocked. Yeah, as you get older, sometimes you could duck sometimes you can weave, sometimes it gets getting off you and sometimes it just misses you all together. But that's that's age. That's experience.

Marshall Herskovitz 17:35

Well, can I tell you, I don't think Ed and I have ever learned how to duck or we've, I think we got one of the worst punches of our career this just this past year in 2020. And we were just destroyed by it just destroyed. And I'll even say what it is we we thought we were doing a reboot of 30 something. Yeah, I had a great idea. It basically, it wasn't a redo. It was basically saying it's another generation, all of their children are now in their 30s. And it's going to be as much about their children as it is about the original cast members. And we wrote seven scripts, and we thought it was going to go and we had our our whole heart and soul in this thing. And ABC decided not to do it. And we were just like, we were undone. So here we were, you know, there was no ducking, there was no weaving that was a straight punch right to the face. Yeah. And, you know, and, and the, you know, the thing about the business, if you're a creative person, meaning if you when I say creative person, we're all creative people, what I need is if you make your living by creating things, either as a producer, director, writer, that sort of thing. This is gonna happen over and over and over again, you have to be willing to endure that kind of rejection, which is not the same as failure failure is once you've made it, and people shit on it, you know, rejection is before you get to make it, and people don't take it seriously, or they don't think it's good enough, or they decide they don't want to do it for whatever reason, you know, and and, you know, the point is, it takes just as much work we have, we put months and months and months of work into that, even though we hadn't shot you know, anything. And it was it was awful. But that's why that's that's the that's the job if you can't handle that you

Alex Ferrari 19:39

can't do this job. And that's the thing that I want people listening to understand because a lot of people think, you know, someone like you and Ed, you know, all all doors are wide open. They just, you know, how much do you need? Marshal? How much do you need and because of your track record, I mean, you guys have an remarkable track record individually and as a team remarkable track records as writers producers and directors. And yet and I've said this so many times I look, I always use the example of Spielberg, but I'm going to use you guys as an example. But like Spielberg couldn't get Lincoln gonna get Lincoln, you know, finance, you have to go. So Scorsese couldn't get silenced finance for 20 years ago. And to do icon Yeah, they're too iconic. And yet, Graham, I

Marshall Herskovitz 20:17

don't read my go, Oh, they should be able to do it. Also, I know it would be

Alex Ferrari 20:21

impossible, right. And you know what I've said that story to other people like yourself, and they're like, you know what, I'm not crying for Steve. I'm not crying for Marty, either. But I understand your point. But there's people at every stage of their career at every stage, no matter what they've done Oscars, no Oscars, big box office hits non big opposite, you still is still a struggle. It's still a struggle,

Marshall Herskovitz 20:45

constant struggle constant.

Alex Ferrari 20:47

And that's what I want people listening to understand that, like, there is no magical place that you'll get to in this career. We're just doors, doors will be wide open all the time. It might happen once or twice. Yeah, after big hit after a big hit. You're that you're the toast of the town. You're the belle of the ball. What would you like, and that's when you stick in that that project that you've been wanting to get done for the last 20 years? Like a medieval Excalibur reboot?

Marshall Herskovitz 21:11

There you go. Correct.

Alex Ferrari 21:15

Now, when you brought up 30 something, how did you guys you and had come up with that? Because I mean, I remember when I was growing up, I mean, I wasn't in my 30s then but I do remember 30 something was a he was a monster hit it was a monster hit for ABC. When it came out? How did you? How did you guys come up with that whole that whole thing?

Marshall Herskovitz 21:33

Oh, there's a funny story behind it, you know, we Oh, my God, you know, I'm trying to figure out how far to back this up. But But essentially, out because we had done this TV movie called special bulletin, which I can talk about later, which made a big splash in the 80s. It was about nuclear proliferation and nuclear bombs and all of that, it kind of put us on the map. And we were offered a television deal at MGM television, right. And of course, we didn't want to do television, we want to do movies. We thought television was you know, shit. And so we took this deal at MGM television, explicitly for the purpose of the fact that I wanted to put a second story on my little tiny house in Santa Monica. And it would pay me just enough money to do that. And the idea was to try to get out of doing anything they wanted us to do, because they were going to pay us a guarantee. But we didn't have to do anything, you know, we were only obliged to try to sell the television series. That's That's it, just try to sell the television series. So the moment came, where we were going to have the pitch meetings at the network's. And, you know, we had come up with ideas for series and I turned to Ed, and I said, you know, these are all terrible ideas. What if we sell one of these? It's like, we would have to make this this is awful, you know, I and so, and this is not a joke. We sat down, we said, okay, what we need is an idea for a series that has no chance of going. But if it goes, we wouldn't mind doing. So we said, What would that look like? And I sat there and I thought well, you know, what's interesting is that on television at this moment, we're talking about now 1986 there is nothing that represents the baby boom generation except Saturday Night Live. And show called Kate nalli.

Alex Ferrari 23:27

Yeah, remember kitten alley? Yeah.

Marshall Herskovitz 23:28

Yeah. And that was it. Everything else would had nothing to do with baby boomers. And I said to add, you know, look, we know all these people in this moment in their lives, they're having babies are messy with their careers, you know, this person is afraid to settle down. And it's very interesting, because ed is normally so open to everything looked at me with this look, he gets, you know, we have the same. It's like, he gets this look, that looks like a grimace. And I go, why are you tilt down on this already? And he goes, I'm not down on it. It's just my face. I'm not making a face, you know, they right? He gave me that face. And he was he was just completely, you know, didn't buy this. And in those days, of course, we had this stupid little office at MGM and and at one in the afternoon, we could just go home because we didn't have anything we had to do. So we went back to his house, and his wife Liberty was there. And I tell her this idea I have Why don't we just talk about people we know know, Ed's will point was, but there are no cops in it. They're no lawyers, no doctors, how you going to sell a television series that doesn't have any of the franchises. And I said what do we care about that? Their story and and God bless her Liberty went, Oh my god, I love that idea. And she started just listing all the people she knew and all the dilemmas in her life. And because ed is added he loves liberty. Somehow when she said it, it made sense to him when I said it didn't make sense to him. So literally by the end of that afternoon, we had sketched out this seven characters. You know, by the next day, we had written this sort of manifesto of the series, we went in the day after that to ABC. And of course, who are the executives in the room, they're all in their 30s. One is pregnant, they were exactly the demographic for the show. And we basically sold it in the room to them. And, and, you know, it was the whole thing was kind of charmed. And the irony was, we didn't want to do it. We did not want to do it. You know, it's sort of, that's when Ed started quoting that great john lennon line of you know, life is what happens while you're busy making other plans, because at every step along the way, you know, alright, so we wrote the pilot. And people loved the pilot, they said, Go make the pilot. And then I directed the pilot, which is the first thing I directed, and they loved the pilot. And then, in those days, they had what was called selling season in New York City, in May, where they would, you know, show everything to the advertisers and decide what they were going to pick up. It's what now it's called, whatever the sweeps, like sweep, sweep, not the sweeps, you know, the the, the TCPA is whatever they're called, up front, basically. But in those days, there were no cell phones. So you were ordered to go to New York and sit in your hotel room for five days and be within range of your telephone in the hotel room, because you might get a call that your show was picked up. So we sat there like idiots for for four days in New York on the on the fourth day, we get a call from the head of the studio. And that's a whole other story. David Gerber, who was one of the greats is such a character. Every second word was it was a curse word. And he says, and he had this, he said, they love this package. Oh, that's great. But you got to change the name. They don't 30 something, make no sense. But you got to change the name, they want to use grownups. And we go grownups. That's a terrible idea. He goes, Well, they don't know if they can get it because she'll swiper older, but they want to use grownups. And we go, Well, we hate the idea. We don't want to use grown up, we want it to be 30 something. So he hangs up. Okay, so we thought it was over, you know. And then of course, the next day at noon, he calls he goes, they're picking up the show.

Alex Ferrari 27:21

So you're actively trying to sabotage, sabotage.

Marshall Herskovitz 27:25

And not only that, I'll go further. We hang up the phone, and he's like, you guys are amazing. They're like, you could hear cheering behind that they picked up the show. We hang up the phone, and we look at each other. And the thing is, Ed, and I have this shorthand with each other. We don't speak very often, you know, in sometimes these situations, we just looked at each other. And we listed, you know, shook our heads, and went for a walk up madison avenue for about an hour, thinking that our lives had just been completely derailed. And now we were doing a television series instead of being movie makers. And in those days, remember, TV was the great wasteland in those days,

Alex Ferrari 28:03

right? It was about to say that it's not the thing like now TVs have no place to be.

Marshall Herskovitz 28:08

Yes, no, we were sellouts. It's like what are we doing with our lives? It's so and I say that in the full knowledge of how stupid we were at that moment. And I delight in our stupidity at that moment. But that's where we were, we thought, Oh, fuck, we sold a television series.

Alex Ferrari 28:25

I guess we're gonna have to go do it now. And that's the thing. That's the one thing I've I've heard this from multiple people in the business. If you want to get rich, you work in television, if you want to be an artist, you go to movies, because because there's a lot more money to be made, at least there was back, you know, when the residual there was much more money to be made in television than there was in syndication and all of that kind of stuff. As opposed to a movie. It's just a one. So it's like,

Marshall Herskovitz 28:54

That's right. That's right. Yeah, nowadays. You're one of those few people, you know, who, you know, the few directors who can make $10 million, a movie or they can make 20. But they're very rare. Very rare, and especially in today's world. I mean, look, the last few movies Ed and I have made literally, we ended up losing money on them. You know, we made a woman movie called woman walks ahead, we ended up not only giving up our fees, but each of us paying $25,000 you know, in the post process, and so we lost money on that film, when you know, so that's, you know, basically the movie business now consists of 90% indie films where nobody makes money and 10% these big studio productions that are $200 million productions, and that's a very small club that makes those movies

Alex Ferrari 29:45

right in you're absolutely right. And I mean, movies, some of the movies that you guys got made, like, glory, I can't see glory getting made in today's world. Sure, you know, legends of the fall. I mean, Even even if even if you still had Brad Pitt and and Anthony Hopkins in it, I'd still be a tough sell as a studio movie, it might be more as a mini major kind of scenario,

Marshall Herskovitz 30:12

we have a follow up to legends of all i don't mean a sequel, I mean a, a piece that said in 1905, not the same characters or anything like that, but it has a lot of the feel of Legends of the fall. We can't get anybody to even consider making that movie because they're, it's just a different world. Now.

Alex Ferrari 30:32

That's all again, super if you put a cape on them. I'm Jeff, hey, I'm nobody. I'm just saying it might be a lot. I'm just trying to help. I'm just trying to help Marshall. So, so obviously, you and Ed have been, you know, you've obviously been great friends since since the AMI days. What is the writing process? Like? What is the process? How do you guys actually do the writing? Like I always love to hear really good questions. Yeah, I love it.

Marshall Herskovitz 31:01

You know, what's funny is that when we started, I did the writing, we would do the stories together. And then I would do the writing. And when I was supposed to write the pilot of 30, something I was seriously blocked. I mean, I was so blocked, that after three weeks, I had written one act. And, you know, he and God bless him. He he came in one day we were, we had these little offices, like I said, at MGM, and he sat down next to me. And he just took the keyboard. And from that moment, we started writing together. We never said a word about it. We never had, we never discussed what the terms were how we would do it, we just started doing it. And it was all Him, He saved me a demo, he literally saved me. And I think over the years, what we've worked out is we just hand off, in other words, some period of time I have the keyboard some period of time, he has the keyboard. And by the way, this works just as well. Over zoom, actually, we use a thing called goto meeting, but it's the same thing. But you can at least look at the document while you're doing it. Or in person. And one person is looking at a monitor and the other person has the keyboard. And basically, the person with the keyboard is kind of the captain of the ship at that moment, the other person talks and yells and says no do this. And but the person or the keyboard says no, I'm doing it this way. You know, unless we scream too much, then you know, but basically, we we listen to each other. Um, we, you know, it's funny, when when Ed and I started out, he had a very specific set of skills, and I had a different set of skills. And over the years, we've learned each other's skills, but he's still better at what he started out at. And I'm still better at what I started out at. And that's part of I think, what makes us such a good team. And, and that differences that Ed has the greatest story sense of anyone I've ever met in my wife. I mean, I used to say, you could drop ed in any story. And in five minutes, he can tell you where it came from and where it's going, it'll his his ability to, understand the schema of what has to happen, what happened before where it has to go, where the other people fit into it is astonishing. And his speed at it's like speed chess, watching him work, sort of structuring a story. When I met him, he didn't really have much skill at sort of depicting how people actually speak or what happens, you know, between people in a scene, and that was my strength. I hadn't a clue what a story was no clue at all. But I could write a scene, I could, you know, get into the nuances of how people behave with each other, and why sometimes people say what they feel or don't say, what they feel and why they sometimes don't talk and why and other times, they can't stop speaking. Um, and so, you know, we quickly learned to respect the other skill. And so if I'm writing a scene, and he would say, why are you doing that back and forth? So many times, I would say just shut up. It's gonna work, you know? And then he would see that it would work because it would all go boom, boom, boom, just like that, you know, two people why? I don't know, we actually know. But you said that, that other people talking over each other. That was something I understood. Whereas he would say, this scene makes no sense. It doesn't fit into what you're doing, I would learn to understand that he's right when he says that. So. So we each apply our skills as it's going along. But there's a certain level of trust you have to have. I mean, I couldn't do this with anybody else. Because basically, you're like, you're you're just saying any stupid thing that comes to your mind. And what we've come to realize, by the way, and I think this is really important to understand is we've come to understand that if there's a moment where you hesitate because you think Your idea is dumb or embarrassing or revealing in some way. That's the moment where the other person has to say, what is that your thing? You're thinking right now? What is that thing? Stop right now tell me what you're thinking right now. Because whatever that thing is, that's going to be great. The thing you fear is going to be bad is going to be the good idea. And so we expect that in each other. And it's a vulnerability, that it's a sort of a mutual vulnerability, where you know that the things that are the truest are the hardest to say, and therefore you're, you're not going to want to say them. And by the way, corollary to that is that we both hate writers rooms. I mean, I, you know, I know we are far outside the mainstream, but I think writers rooms are terrible places for just that reason. Because the best ideas can't be said in front of eight people. It's too revealing to say it in front of eight people. And so when we do our shows, we don't have writers rooms. I mean, we bring everybody in, and we will sort of talk about the season in general. But then when we're working out each episode, we bring that writer in and we we we get we we work out the outline for that episode with that writer and let that writer going right in. And that works out much more efficiently. And with a much better product, we feel for that very reason. Because people then are less afraid to say what they're really thinking.

Alex Ferrari 36:25

Now, you talking a little bit about fear, and breaking kind of because there's this whole town is run by fear. Let's just be honest. Everyone in the entire town is run by fear. This entire industry is run by fear. And it's getting worse and worse and worse as the years have gone by even in my short tenure in this business.

Marshall Herskovitz 36:46

I've seen the corporate America is run by fear. And now the movie business is corporate America. Exactly.

Alex Ferrari 36:52

So you always so did you ever write a loan before at or did you guys just start and just that's

Marshall Herskovitz 36:58

not always I wrote alone? I but we both wrote alone? I wrote a bunch of things alone before. Yes. Okay.

Alex Ferrari 37:04

Okay. So my question to you is, when you decided to say to yourself, I want to be a screenwriter. And you sat down and you saw a blank page, because I'm assuming there wasn't a screen at that point, it might have been more likely might have been a page or a screen. And up to you,

Marshall Herskovitz 37:18

though, it was a page, it was a bit.

Alex Ferrari 37:20

So when you looked at that blank page? Yeah. What did you say to yourself to break through the fear of actually starting to write because it is the most terrifying thing for a writer to see a blinking cursor, or a blank white page, it is a terrifying place to start.

Marshall Herskovitz 37:34

It's the most terrifying thing. It's the thing. And by the way, I would say did me and for 20 years, I mean, I think why was I blocked when I was writing 30 something because I have that fear you're talking about? I just, I couldn't break through that fear. I think, look, I'm a I'm a big proponent of psychotherapy. And I think psychotherapy in particular, when it comes to work, when it comes to the creative process is incredibly valuable. Because each of us has a voice inside our heads. That is self loading. Then you just wrote us a piece of shit. And it instantly goes into we'll tell you exactly. We humiliated you will be when people read that horrible thing you just wrote, and it's paralyzing. That kind of fear is paralyzing. That's shame. It's really shame is what we're talking about. Writing is so filled with shame, because you are exposing yourself. And you're exposing yourself to the worst kind of criticism, shaming criticism, how could you have thought that? How could you write that you bore me, you know, you're uninteresting, you're bad, all of those things. So you have to develop the ability in yourself the compassion in yourself, to say, I'm going to write this anyway, even though I might be shamed. You know the words it's about letting the shame wash over you and realize you survive on the other side. Now, Ed's wick, who is less afflicted by shame than I am, although he certainly is afflicted by it, for sure. But he's, I think we're able to cut through that his invoice is right at bad. In other words, go right for the shame. Just write it bad. Because it won't be that bad anyway. But the point is, except that it's going to be bad and write it anyway. Because you can always rewrite, rewriting is much easier than writing. I think, once I learned that, once I learned, I could try a scene. And if it's bad, it's going to take me 30 minutes to rewrite it anyway, what's the difference? It was very freeing. And so it's much easier for me to write now than it was 30 years ago because I was so consumed with shame and fear of shame at that time, so I feel for every writer, this is our lot in life issue is to face that shame. Every single day, but it's to understand that it's shame. That's what you're afraid of, is shame

Alex Ferrari 40:06

at the I've said this on other episodes about this, and it's something that I've, I think all creatives go through, but I think we, we, we go through it a little bit more as filmmakers and screenwriters is, the ego is a very dangerous, dangerous thing inside of ourselves. And that that voice that you're talking about, I always use the analogy is, if you go out and you have a big meal, and it's you're stuffed, and then the dessert tray comes, that voice in the back of your head goes, go ahead, have the cheese cake, you just work out tomorrow, it'll be fine, then you get the cheesecake. And then later that evening, when you're at home and you're undressing in front of the mirror, that same voice goes you fat pig, hi, could you have eaten that damn cheesecake. And that is, and that is the voice. And this is similar voice to the shame voice that you're talking about. You can have voices the one that got you to write, but then the other one, but it's also going to shame you it's it's it's horrible thing that we have to deal with,

Marshall Herskovitz 41:04

as human beings, as human beings. And by the way, I see it as two different voices. Okay, I see, we all have parts. And that's what I believe we all have parts. And there's one part that's a shaming part. And there's another part that has the appetite and the desire and wants to be a big deal or be creative, or be famous or be rich or any number of things. We have different parts, you know, and the problem is at any given moment, one part is Ascendant and the other part is pushed down. So yes, you look at that cheesecake, and the part that says, Oh, I can do this takes over. And then the next morning, the shamer says, You idiot, why did you do that, you know, and, and it's learning how to live with them, and, and sort of figure out some middle ground between all these voices. And also, I believe, very strongly at this point in my life, in the idea of compassion for yourself, I think that's the thing I did not have, for many, many, many years, I had no compassion for myself. And I, you know, I think most people would have described me as a very compassionate person toward other people. It was something that was very important to me, I had no compassion for myself. And that was very hard won and hard fought. And it's changed my life to be at a point where I do have some compassion for, you know, why I became that way why I'm so susceptible to shame. And here's the problem. People don't go to Hollywood, we go into this business, if they're all right up here.

Alex Ferrari 42:38

I've said that 1000 times

Marshall Herskovitz 42:40

1000 times some hole to fill, you know, you've got some deficit that you're trying to get over from your childhood, if you're out, you're trying to do this, instead of going into the family business in Pittsburgh or, or becoming, you know, what I mean? Honestly, they're, they're, we are propelled by by darkness, you know, in many ways to do this. And that, that's a part of our makeup that were damaged in some way. I believe that and and I have a lot of compassion for that, you know, other people and in myself, and as you know, I like the percentage of damaged people in the film is this must be higher than than other, per capita,

Alex Ferrari 43:21

or industry, per capita.

Marshall Herskovitz 43:25

I mean, patiently, you're surrounded by crazy people of one kind or another. This is one of the few, this is one of the few industries that rewards you if your bipolar rewards you if you have ADD, you know, rewards improve things that would normally harm you in other businesses. So, you know, look, we we are that thing about the tilted the country and all the nuts and bolts, all the nuts went to California, there's some truth to that, you know, because, because there was an ache that brought us out here to try to achieve something and you have to understand that that ache, that's never you're never going to find a source of that in success, you're going to find a source of that in healing yourself.

Alex Ferrari 44:08

Yeah. And I would agree with you. And I think that's something that a lot of writers go through is that that self compassion, and I mean, in my early years, and even into my mid to late 30s, I was brutal to myself, brutal, I just would just pound myself and beat so hard and literally just tear myself apart, where I was more compassionate to people outside of me. And it took my wife to be pointed out to me she's just like, you've got to stop Do you can't beat yourself up about that. Till Finally I I finally get into the place where I'm like, I gotta I gotta give myself a bit of a break, man, because it's, I'm only hurting. You're only hurting yourself. You're hurting your chances only makes it worse. The only makes it worse. It's tough enough, and it's tough enough. Yeah, it's really true. Now you you have gone through a lot of ups. You've got you've gone through a lot of ups and downs in this business, you've been at the highest of highs, and I'm sure you've been at the lowest lows. How do you handle? How does the the psyche, the ego handle, you know, being at, you know, the Oscars, you know, with a project or and then having 30 something, your new 30 something completely just get punched in the face? How do you deal with that at different stages of your life? What's your advice for that?

Marshall Herskovitz 45:27

Well, I think, you know, it's it's along the lines of what we've been talking about, which is, is understanding that, that you're free. There's a, there was a wonderful book 20 years ago called iron john by Robert Bly about what it is to be a man. And a lot of people made fun of that book, because there were all these men's group that respond from it, which were kind of silly, but the book itself is filled with incredible wisdom. And that book helped me understand the idea that, you know, that that failure is part of the lifecycle, and that no man can really avoid failure forever. And that, you know, you have to embrace failure. And so I think understanding that as a big, big help, but it's Look, these blows are just, you know, I had a terrible thing happened 1314 years ago, where I had a startup called quarter life, that was a, that was a social network, and also show an online show. And the online show was successful for a while, but the social network failed, because at that time, the whole point of our social network was it Facebook was only open to college students. And we thought, Well, what happens when you get out of college? You know, and of course, right, when we were developing our website, Facebook just opened itself up to everybody. So our entire financial model went away. And I lost a huge amount of money in this, this was a huge humiliation for me, and not just humiliation, it was destructive. And it was horrible. And I had to say, you know, what, I took a chance, this is something I believed in, and I took a chance and it didn't work, and I gotta move on, you know, and so, that took a while, but you pick yourself up. If you if you still have that fire inside to do something, then you have to listen to that and and say, there are more challenges ahead. So that's all you can do you live with the shame of that and you you move on.

Alex Ferrari 47:36

I mean, look, Katzenberg, you know, put out to put out kwibi. And yeah, he took a swing, he took a very billion multi billion dollar Swing, swing, and you know what, and he he was he was chatting, he was taking a chance and he's like, you know what, I think this is where it's going. I have a pretty decent track record. I think this is what's going and on paper it seemed like a solid investment. But unfortunately, it didn't go up but you know what, I give them nothing but props for taking the swing. You got to gotta have people like that. If not, you know, if it wasn't, you know, for SpaceX or Ilan Musk, or or Ford or Edison, or jobs, or any of these guys who took those big swings in every aspect. We wouldn't be where we are today. So Oh, boy, that's that bravery. And I think as a creative as a screenwriter. Sometimes you got to take that that swing as well.

Marshall Herskovitz 48:26

Absolutely. I I've lived that way I believe in that. And I and I'm willing to take my lumps because I believe in that because you will because you're going to take lumps if that's the way you're going to live.

Alex Ferrari 48:39

Again. No question. Now I wanted to I wanted to take you to your first your first directorial debut jack the bear with Danny DeVito. I love that movie. It was it came out during my my window, my window in the video store. my years at the video store came out so I remember recommending it. I remember the Bach the VHS box on the stage. Like, like I tell a lot of my guests 87 and 94 I'll beat anybody in Tripoli will pursue one movie serviette because that's the time I saw everything that came out. When you when you did that film, which was a wonderful film. You didn't write it you directed if I'm not mistaken.

Marshall Herskovitz 49:16

It was written by Steve Zaillian

Alex Ferrari 49:17

right, not about he's he's okay. He's done. Okay. He's done okay for himself. Um, what was the biggest lesson you learned directing that film? Because I'm assuming I know you direct to some episodic at that point. But

Marshall Herskovitz 49:29

yeah, you

Alex Ferrari 49:30

were you were you were you were at the game. You were at the at the Big Show?

Marshall Herskovitz 49:35

Well, I learned a lot of lessons from directing that film and most of them were negative lessons. Um, it was a very difficult film very, very difficult. There were a lot of problems attendant on that film. And, And truth be known. In retrospect, I think I should have withdrawn and not made it actually. And that's a hard thing to say. Yeah. But, you know, without going too deeply into it, here's here's the issue. I think that although I think Steve Zaillian is one of the greatest writers of our, of our industry, that script has structural problems when I got to the project, by page 60, you did not know what that story was about. And and I don't think a movie can sustain that. And so I, I wanted to make some serious structural changes in the first half of the movie. And Danny DeVito, who at that moment was very ascendant in his career. He was actually prepping hoffa, which was his going to be his big

Alex Ferrari 50:43

directorial,

Marshall Herskovitz 50:45

big, big directorial project. You know, he had script approval, and Dan and, and Danny love the script as it was. And so they would not allow me to make any changes in the script. And I knew that it didn't work. It was a wonderful script, from page to page, in the scenes, the dialogue, you know, was wonderful, but structurally, it was very problematic. And, and so, I remember, it's very interesting. Danny and I had an interesting relationship, you know, in pre production. We argued a lot about the script. And, uh, and he is he, he's a very smart guy, Dan, and he got, he saw what my fear was, and he and he went right to it one day, he said to me, he said, Look, you're the director of this movie. And when we're shooting this movie, you tell me to stand here, I stand here, you tell me to laugh. I laugh. But right now we're talking about the script. And, and that's what's important. And, and he understood that I, as a first time director, I had anxiety that I was working with this big star, you know, and he was true to his word, you know, as an actor, he was great to work with and, and, and cooperative and, and collaborative. You know, the issues were about the script. And we went ahead and shot the movie, we had a lot of issues in the shooting, because the the, the, the schedule was too short. And I knew it, and the people in production knew it. But the studio didn't want to spend more money on it, because it was a soft kind of movie. And so we went behind schedule, as I knew we would, and got into big fights about that. But the big problem came in editing, the problem came in editing, because when we put it together, sure enough, the beginning part didn't work, as I had told them, it would not work, because, you know, it just it was it needed to be sort of condensed into something that you understood where you were going. And so they wanted to fire my editor. I said, You're not firing this editor. This is a guy Steve Rosenbloom, who we've worked with, both at and I've worked with since film school, who I think is the most brilliant editor in Hollywood. And, and, you know, I put my body in front of him, they actually brought in a second editor in addition to Him, who finally gave up saying, I don't know what to do with this. And, you know, we spent a year just editing that film. That's unheard of less than three months editing a film, three, four months, tops, editing a film, you know, a year just editing. And finally came up with something I suggested two days of reshoots to help knit some things together. And they gave me the two days of reshoots, and we were able to sort of create, you know, sort of knit together the story in such a way that that beginning part worked. And so, you know, it was a difficult painful process it you know, as a first movie, to have to do battle with the studio head to do battle with your star and all of that. It was it was, it was tough. It was tough. And then it came out and of course, did no business at all. And, you know, and critics, here's an interesting thing that I that you know, it you know, we talked about you you never see the bullet that hits you.

We, we knew the problems were in the first half of the movie. Once we got through the first half of the movie, it worked like a top. Okay. And so I'm sitting there with my editor Steve, in a in the first preview, and the audience is laughing and they're into it and we get to halfway through the movie and they're clearly loving the movie. And we're like high fiving like we solve this and then you get to that last part of the movie where it turns dark right and you know the the neighbor Norman you know, attacks the boy and oh, That you could feel the energy in the audience change immediately. And we realized, oh my god, people don't like this at all. And what I realized is that when you have a tone change in a movie, late in the movie, people don't like it doesn't mean it's not good. It means they don't like it. There's a difference, in other words, that they thought it was one kind of movie, and then it became a different kind of movie. Now, when you look at the movie, I put in 100 warnings, what's coming? Some of them, I think, very overt, of like, watch out, watch out, watch out monsters are real monsters that are real. But people don't listen to that. Do you know what I mean? They were taken by surprise. And they thought it became a different kind of movie at the end. And that was, you know, critics hated that. And, and it did no business. And so, you know, I look, I look at the movie. And to me, it still works as intended. And I think those warnings are there, and they work. But for audiences, it didn't work. So, you know, I learned also that you have to think, like an audience member,

Alex Ferrari 56:12

you can't

Marshall Herskovitz 56:12

just think, as a filmmaker. And now when I am writing, and when I'm directing, and when I'm editing, what I'm doing is on the audience, I'm not just the Creator, I'm the person. I'm looking through both sides of the telescope. And I'm saying what is my experience as an audience right now? And is it what I expect? Am I disturbed by it? I'm disturbed in a good way in a bad way. Am I taken out of the movie? I think about that much more seriously than I did before that process. So I think there were lots of lessons from that movie.

Alex Ferrari 56:51

So I love I love the concept of the tone changes because that is something that's a very dangerous thing to do in a film is to change the tone because you'll lose your audience. And the the, the one film that always stuck with my head is a Tarantino film, which he wrote but didn't direct which is called From Dusk Till Dawn, which was the first half of the movie is basically a kidnapping heist film right? Out of nowhere, vampires show up. And then the, and then it turns into vapor. And the tone shift just jars so jarring. There's nothing before that tells you. Hey, there's some vampires coming out even a poster on the wall. Nothing. Nothing. So that's something that writers listening really careful with that tone change because it can really just throw you off.

Marshall Herskovitz 57:38

Yes. Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah. It's it's just one of those things. It's the difference between movie reality and real reality and real reality. Shit happens. You know, all of a sudden, you have a car accident and your life just changed.

Alex Ferrari 57:52

Tone shift, but tone shifted. Yeah.

Marshall Herskovitz 57:54

But but in movie reality, there has to be some unity of of not just tone of character of Overwatch thing. So that's what's what people expect.

Alex Ferrari 58:04

Yeah, like, you can't have Darth Vader all of a sudden be the nice guy at the end. Like, it's that that doesn't but but yeah, I've seen that happen in bad movies with characters that just, yeah, they weren't the guy. They weren't the kind of character that would kick the dog. But then halfway after halfway through the movie, they kick the dog. You're like, wait a minute, I know, No, you can't. You can't take me down a road. And then Sucker Punch me like that.

Marshall Herskovitz 58:28

It's Yeah, yes.

Alex Ferrari 58:30

It's very, very tough. Now, another project you were involved in as a producer, which I would love to hear any, any stories behind the scenes or how you even got involved with it with traffic? I mean, that that is such a I mean, obviously, it's at this point in legendary film, I remember when it came out. It's, it's bizarre Berg, who's, you know, brilliant, and so on. But, yeah, it was a risky film, like the way he shot it the way you constructed the storylines. How did you how did you get involved the movie? And how did that go?

Marshall Herskovitz 59:00

Well, first of all, that was mostly Ed. I mean, Ed wanted to do a story about the war on drugs. And, you know, I, I think, I think my participation in that was more supportive than than most of the things especially because, you know, we didn't write it. We didn't direct it. I mean, Ed was going to direct it. But when he found out that Soderbergh was doing something very similar and had the rights to the traffic miniseries, you know, he called Steven I'm sure he had told the story that he called.

Alex Ferrari 59:32

He didn't he didn't tell us Oh,

Marshall Herskovitz 59:34

it's very, very interesting, because he was kind of stuck and on, on how to make it work. And he called Steven and said, Listen, we don't know each other. I know you're doing this thing. We're doing the same thing. Let's not try to do two things. Let's work together. Would you be open to that? And Soderbergh just said, done. That was it. That was the whole conversation. You know, so from that moment on, you know, yeah, he was gonna direct it, we were gonna produce it. And he kind of, you know, got it together in such a way that the script worked and went and did it. And look, we had no interest in telling Soderbergh what to do. I mean, he was, he's amazing, you know, and, and we learned a lot from him. He has such a different style from us. And I just wanted to see how he worked. And I'll tell you an interesting thing that happened. You know, it's basically three or four different movies. I mean, the casts in their stories almost never saw each other. Okay. And yet, there's this incredible consistency of performance throughout the film. And I remember I was doing a panel when the film came out with with two of the actors. And one of the questions was, how did Sodor How does Soderbergh work with the actors? And they each said, Soderbergh never said a word to me. He never gave me any direction. He just I was so shocked, because you know, I spent a little time on the set, but not enough to really like, you know, first of all, Soderbergh was the operator.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:20

Yeah, he's he's the DP Yeah.

Marshall Herskovitz 1:01:22

And so you know, you're he's right there with the actors, you're back with the monitors. I didn't really know if he was talking to them or not, you know, so. But I was shocked that he, they said, literally, he didn't talk to us. And I, and it's funny, Ed has a theory that, that, you know, that a lot of directing is osmosis in the sense that your bio rhythms as a director, get transmitted to the actors? And you know, and and so you have to be very careful what your biorhythms are, because it's going to affect their performances. And what I realized at that moment was that Soderbergh if you know, him, he's very taciturn. He, he's not that expressive as a person, which I think puts a lot of people on edge and makes him seem very serious. He's actually not that serious. He's very funny guy, but he seems very serious. And but I think actors, when they're around Steven, they know they can't fuck around. They know they have to show up. And there's something about his, that that fear of being judged, because he's not judgmental. I'm not saying that. But when somebody is not expressive, or reactive, you put it in, you put out that thing, right? You know what I mean? Right, right. So I think having this guy six feet away from you holding the camera, and sort of in the scene with you had the same effect on every actor, which brought out sort of their A game, their most grown up self, you know, and, um, it's an amazing effect, that, that, you know, in some alchemical way, he got these consistent performances from everyone because of who he is. And that was a very interesting lesson for me.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:18

I mean, because the cast was I mean, the cast was remarkable and so many different styles of actor and actor

Marshall Herskovitz 1:03:26

yeah and performance are wonderful and they're so every single one of them is so internal and so available when I say internal it means I can see into they're actually not internal they are they are their windows of into their thinking process is so open, you know, and Benito Del Toro is, is sublime, just sublime. In the movie. It's like, just watching the dailies you're going this guy, I it's like, you can't even imagine. You can't even call it acting. It's something else. It's some it's some. He's some possession, possession, possession, whatever it is, you know, um, and Michael Douglas and all of them and Don Cheadle. They were all Catherine's place. Yes. All over some place that was so remarkable. And, you know, that's Soderbergh's gifts that he creates that that world on the set that allows these actors to to inhabit that place in themselves.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:27

Is that the is that the first app? Please remind me because I mean, I'm not I'm not that keen on Soderbergh's history, but was that the first time was the big hit cuz I know Erin Brockovich, and obviously the documentary was the same year.

Marshall Herskovitz 1:04:43

He was nominated. He's one of the first he's one of the only directors should be nominated against himself as a director cheese or an Oscar. He was up for two Oscars as director that year. And, and

Alex Ferrari 1:04:56

and Best Picture two,

Marshall Herskovitz 1:04:57

I think right black Best Picture. Yes, yes. He wants to traffic. He wants to record. You want director for traffic. And I remember telling him on the phone I said you just have to beat that asshole Steve Soderbergh?

Alex Ferrari 1:05:10

I mean, he's everywhere. This guy, this guy is everywhere. I mean, he left.

Marshall Herskovitz 1:05:15

And by the way, when we were at the Oscars, it's just so terrible. You know, you're, we're in the second row. And you can see into the wings at the, in the in the auditorium. Right. So Michael Douglas comes out to give our best picture. And you could see that first of all, they had three Oscars for best picture, and we had three producers. And then as he opened the envelope, I can see that the film is one word. I couldn't read it, but I could see it's one word. And so I hit head, and I whispered, we won. And he goes, and the winner is Gladiator, which was one word and had three Oscars. You know, it was, it was one of those great, horrible moments where we thought we won, but we didn't. But you know, so what?

Alex Ferrari 1:06:05

Yeah, it was all No, I made it. Overall. It you guys did. Okay.

Marshall Herskovitz 1:06:14

You know, just don't get ahead of yourself more. Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:18

And honestly, talking about you know, guys who swing take swings at the plate. I mean, Jesus Sonnenberg I mean, he's not making use of his iPhones. IV is

Marshall Herskovitz 1:06:30

really absolutely remarkable. So much respect for him.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:33

I have to I have to ask, when you start writing? Do you add, start outlining first? Do you start with character? First, you start with plot first? How do you how do you start that process?

Marshall Herskovitz 1:06:44

It's a good question. What we have learned over the years, is not to try to structure anything at first, including the conversation. In other words, so much of what we do when we're starting something is just talk, talk about how we feel about it talk what what is it what ideas come to mind, how do we see the characters but not not in any organized way, we will just go from history to things we've read to what this reminds us of this is like my aunt Marcy, this is whatever, you know, that, that we just kind of inhabit that space. And that could go on for a week, you know, we're more where you're just kind of living in it. And, you know, it's like somebody wants said, you know, if you are want to make a sculpture of an elephant, just cut away everything that doesn't look like an elephant. Yeah, you know, that in some way the thing exists there. And you have to just pull it out that in some way, that's true. It's just harder when it's something like this, that's a story. But we still believe that in some way, it exists. And we have to find it. And that means being open to the most gossamer foggy notions that might be true and be willing to change and follow something down a line. And so it's the willingness to be unguarded and unguided in that beginning part that allows you to really start to have a sense of what the thing is, and then, you know, then we talk about the characters a lot. And I think we get to structure at the at, that's the last thing, you know, there may be some things we know we want to happen. Or we know we want the person to be this kind of person. And so that's going to dictate certain things are going to happen. But but to actually structure the story. That's the last piece of the puzzle for us before we start writing.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:40

Now, there was a movie you did that was in your filmography, that kind of like one thing, like that old song, like something in this thing doesn't belong, which was jack, jack Reacher, which is, I think the only sequel you ever did, right? And it's, you know, it's a, it's a, you know, Tom Cruise vehicle. It's an action movie. Obviously, there's a lot of action and a lot of like, Last Samurai and other things you've done, right? But this was different. How did you guys approach this? And I mean, when I spoke to Ed a little bit about it, he's like, I've never done it before. So I kind of just wanted to try it and see if I could do it. How did you guys approach the writing process of that?

Marshall Herskovitz 1:09:16

Well, I think, you know, first of all, I mean, I'll talk about this I I tend to not want to talk about anything that pertains to other people what other people said or did and so I'm going to be a little bit circumspect, just out of respect. Sure, those people. But basically, the idea behind that film was to take one of the novels where Reacher is in relationship to someone, because usually he's not that much in relationship, because they wanted to humanize him a little bit. And so they picked that novel. And so our mandate was to and I think why they used us was because they wanted the relationships they wanted that sense of connection between him and the woman and the girl. And that's what we wrote. And that's what Ed shot. And they loved it. And I remember Tom, who we love working with, by the way, we're going to movies with Tom. And he's a great guy to work with. So he's, that's a whole other subject.

Alex Ferrari 1:10:22

No, I mean, I've heard john

Marshall Herskovitz 1:10:24

out. I'm happy to get into but he is. He's, you know, who was it? Who said, Tom shows up on the set each day and basically says, How can I make your dreams come true? I mean, that's how he looks at movies, he's full of gratitude, and wants them to be great. And it's so it's a great experience. So at any rate, we made the film, Tom looked at the film, he turned to Ed, and he said, this fucking film made me cry, none of my films make me cry. You know, thank you, then we test the film. And women love it. And young men go too soft. In other words, the idea didn't work for the intended audience of the movie. Now, have I said too much? Maybe? I don't know. But what the hell, it's past history. So we, you know, we did some work on it didn't take that much. We did some work. We we did some things together, we shot a little bit more action, we just kind of toughen it up a little bit. And that's something I believe in I look, I believe in the post production process very strongly, maybe because of my experience with jack the bear, but maybe also even from television, that you can surgically change something and make it into something that works better. And and we've done that a lot. And so that's what we that's what we did with that. And, um, you know, I think it's, it's, you know, it sounds some audience, it's just, it was each of these things looks to me, it's a miracle movie ever gets made. Amen. Is it good? No, I don't I look at that. And I go, Okay, I'm proud of it. We, you know, we did what we were supposed to do, and and then we did what we could do, and a lot of people liked it. So you know, if it's not the most popular movie of all time, we can survive, you know,

Alex Ferrari 1:12:27

and, and I've spoken to multiple people who've worked with Tom and they say, I've never heard of a negative word come everyone's always like, he is the utmost professional,

Marshall Herskovitz 1:12:38

he shows up, he just is can I tell you, when we when we did Last Samurai with Tom, and we went to New Zealand. After we'd been there a week, it was an article in the local paper saying that everyone on the crew had to sign a affidavit that they would not speak to Tom and they would not look Tom directly in the eye. And not only was that not true, but the opposite was true, which is of all the people I've worked with, he's probably the most polite to fashion on the crew. If someone says hi to him, he will actually stop and say hi, how are you and talk to them? You know, he's incredibly available to people. And I suddenly realized, maybe that's never been true. Maybe there's never been an agreement where you're not supposed to look at the star. You know, we could we all think that that's like something that that people have and I thought maybe it doesn't exist because it certainly wasn't true with him.

Alex Ferrari 1:13:39

I mean, I'm assuming you don't want to be in an actor's eyeline. But that's just being professional.

Marshall Herskovitz 1:13:43

That's different. Yeah, different. That's just a that's just a matter of, and in fact, that that's just understood on the set. And anyone who is in the eyeline, we usually tell them to get out because it's just not nice to them. You know, that's different. It's called

Alex Ferrari 1:13:56

being it's called being professional bf. I've heard all the, I only want green m&ms. In my in my trailer, I heard that actually, I actually heard that the origin story of that, which was really the origin story, too. I can't actually say I'll tell you off there. Because there's it's a little it's a little saucy. But heard the story of that one. But yeah, you hear all these stories and look, you know, talking to a lot of a lot of people like yourself and professionals in the business when they work with these big actors. The amount of attention and and you know, that gets thrown on someone like a Tom Cruise or Will Smith the rock under these giant movie stars. A lot of times it sells papers. It's sensationalism. And a lot of times they want to tear tear them down. A lot of times. It's just a

Marshall Herskovitz 1:14:48

weird thing that with Tom. And by the way, the thing that always hurts so bad for me, was that thing about him jumping on the couch for show It's like, that's Tom every day, almost the most enthusiastic person I've ever met. It's like when we did the final battle of Last Samurai, and I came up with a set that day. And we have 500 men on each side, and he's in the full Japanese armor. And we've got seven cameras up on towers. And Tom comes over me and he grabs me by the chest, and he screams at me. This is fucking great. It's just fucking great. That's Tom. He does love the guy. He's the most enthusiastic person in the world. Why would you make fun of him for jumping on a couch? It's like,

Alex Ferrari 1:15:37

God bless him. They always wanted they always want to tear down and that's the thing. Look someone like Tom and then we'll stop talking about time because I could talk about Tom forever. I've been a fan of his since since the beginning, since all the right thing all the right moves. There is a charisma that these these these stars have, there's an energy that they project on the screen. There is a reason why Tom Cruise has been a movie star for 30 plus years. There's not a lot of movie stars. who have been who are still

Marshall Herskovitz 1:16:06

movies. Exactly, exactly.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:10

movie star, he's still the biggest movie star in the world. He really he green lights a picture today, just like he did in 1990 after he did Rain Man, or Top Gun or any of these things. So there's a reason there's a reason for that. Yep. And you gotta kind of respect that about him. Yeah, look, we all have. And we all have bad days. And of course, when you have a bad day, and you're Tom Cruise, it's news. When you and I are having a bad day.

Marshall Herskovitz 1:16:38

nobody hears about it. No one cares about it.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:41

Now I'm going to ask you a few questions. I asked all of my guests Marshall. What are three screenplays every screenwriter should read?

Marshall Herskovitz 1:16:49

Oh my gosh, that's such a good one. Um, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Alex Ferrari 1:16:54

comes up very often.

Marshall Herskovitz 1:16:56

Yeah. Um, Chinatown for sure. And I would say Annie Hall, probably. Because I'm Annie Hall. It's funny, because everyone's talking about this right now. And it's been a, it's been a very particularly difficult experience for me, because Woody, first of all, Ed has known woody since Ed was 23 years old. And in relationship with him, and he's not just a hero of ours, you know, creatively, he was such a touchstone for us. And, and, you know, it's just been a very painful, painful experience. And, and the only way I can live with it is to understand that many of the artists that we revere turned out to be monsters. Picasso was a monster, Wagner was a monster, a lot of people, you know, and, you know, artists art, and I cannot take away the fact that, you know, of, you know, Annie Hall is probably my second favorite movie of all time. And that's just will continue to be a fact because he packed so much about what it means to be a human being and what it means to be in relationship into that movie. It's, it's amazing, and you can't take that away from him.

Alex Ferrari 1:18:18

So I mean, how do you in that's a conversation about being able to separate the artist with the art. And, you know, his van, you know, his van Gogh? Do I appreciate Van Gogh differently? Because the way he lived his life? Yeah. I don't know. And that's a that's a much deeper question and a more controversial conversation to have. But at the end of the day, you know, any halls any hall?

Marshall Herskovitz 1:18:46

Yeah.