One of my pet peeves when it comes to art is when someone from a particular artistic discipline decides they want to try their hand at film directing. In practice, it’s a hit or miss proposition: for every successful transition (Steve McQueen, Tom Ford, or even Ben Affleck), there’s an abject failure (Madonna and…Madonna).

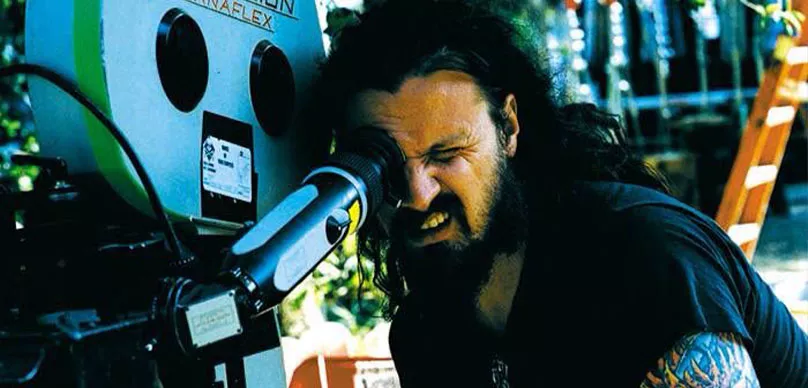

When shock rocker and frontman for the White Zombies, Rob Zombie, announced he wanted to be a film director, I’m sure many eyes rolled.

And understandably so—nothing he had done in his career up to that point had pointed to any inclination towards directing. In hindsight, Zombie’s case proves the danger of boxing an artist in, as they are often just as talented in other forms of expression. Zombie’s films are often negatively received, mostly due to preconceived notions about his celebrity or identity.

Despite this, he has cultivated a strong cult following over the course of five features and established himself as an undeniable auteur with an unmistakable stamp.

Whether that stamp appeals to you or not is simply a matter of taste.

Earlier in this project, I examined indie director Ti West’s career, and it’s my particular belief that West and Zombie are something of kindred spirits as far as their art is concerned. Both have looked to an old-school 70’s/80’s aesthetic for inspiration and execution, and as a result, their resulting works stand out from the pack as fresh and original.

While they operate on different planes (West in the indie realm and Zombie handling the mainstream studio side), both directors have positioned themselves as the new vanguards of the genre, aided by an encyclopedic knowledge and respect for the masterworks that came before them.

I often find that the occupations or interests of an artist’s parents often influence his or her work. For example, my father is an architect, and I find that profession as well as the general idea of structure and functional design to be recurring themes within my own work. Mr. Zombie, born in 1965 under the distinctly un-hardcore name of Robert Bartleh Cummins, was also profoundly influenced by his parents’ profession and incorporated it as a recurring theme in his work.

His parents worked in a carnival in Haverhill, Massachusetts, so those viewing Zombie’s filmography in quick succession should not be surprised to see the heavy usage of circus imagery. He attended college at Parsons School of Design, and soon afterwards pursued his first passion: music. Taking the stage name of Rob Zombie, the young Robert Cummins assumed the frontman position in a shock rock band called White Zombie.

The genre gained significant popularity in the 80’s and 90’s, bringing similar acts like Marilyn Manson to the fore. Zombie’s shows always had a penchant for over-the-top theatricality and Halloween iconography, which was appropriate given his stage name. However, being a famous rock star only satisfied his artistic urges so much, and it wasn’t terribly long until Zombie felt the pull to the cinema screen.

MUSIC VIDEOS (1995-2001)

For Zombie, directing music videos for his band must’ve seemed like the best way to break into the field and hone his filmmaking skills. In 1995, he began his film career with a pair of videos for White Zombie. The first, for their song “MORE HUMAN THAN HUMAN”, establishes a few tropes that would become commonplace amongst Zombie’s music video work.

The piece is anchored by a stylized performance element, edited together with mixed media (oftentimes heavily-scratched found-footage elements like home movies or newsreel footage). He mixes the various source formats together and goes for broke with his color timing, adding lots of filtration and lurid colors.

You can say many things about this video, but one thing you definitely can’t say is that Zombie doesn’t have a clear idea of his own brand. The piece is unified by an overall carnival-inspired aesthetic, with the heavy usage of costumes, masks, and Halloween paraphernalia. In short, Zombie’s first video is short on substance but long on texture.

His second 1995 piece, “ELECTRIC HEAD PART 2 (THE ECSTASY)”, is also mostly performance-based, again incorporating a scratched-film/circus aesthetic. He switches between color and black-and-white footage without any apparent rhyme or reason, so the idea of restraint hasn’t yet entered his mind. What is most notable about this piece is that we can see the elements of the aesthetic that would inform his debut feature HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES (2003) beginning to coagulate.

His third video for White Zombie, “I’M YOUR BOOGIEMAN” (1996), really brings his love for Halloween iconography and costumes front and center, while also incorporating coherent story elements. He uses the framing device of one of those schlocky old horror TV programs for children you’d see in the 50’s or 60’s. This “Dr. Spooky” element also foreshadows a similar conceit he’d use to open HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES (which may or may not have inspired a similar technique that Ti West used in his own 2005 debut THE ROOST).

The requisite performance element of the video is a stark contrast from the Dr. Spooky framing device, bursting with lurid color and a gothic-rave style of production design. With “I’M YOUR BOOGIEMAN”, Zombie is beginning to show more of a restrained focus and a unified vision. He’s beginning to make curated directorial decisions instead of appearing to throw everything at the wall and see what sticks.

1996 also saw Zombie directing for a band that wasn’t his own. For the largely-forgotten 90’s band Prong, Zombie delivers“RUDE AWAKENING”, a veritable acid trip of a video. His visual approach combines bright, candy shades of color with a low-key, dark lighting scheme during the performance elements.

He further warps the frame with a post filter that resembles the effect of tripping on LSD (not that I’d know). All of this is juxtaposed with black and white footage of people in costumes and masks for a grotesque, carnie effect.

The footage itself is expectedly scratched and grungy, with film artifacts that suggest some self-processing. “RUDE AWAKENING” also takes a page from the darkly glamorous stylings of Betty Page, adding a touch of burlesque footage in the first instance of what would become another visual hallmark of his work.

In 1997, Zombie directed a video for the band Powerman 5000, who his brother happened to be the frontman for. Putting aside the fact the song itself is terrible and entirely indicative of the scourge of the 90’s music scene that was nu-metal, Zombie’s “TOKYO VIGILANTE #1” adds another dimension to his body of work.

It’s once again a visual hodgepodge of scratched film effects, lurid colors and mixed media footage (kung-fu movie scenes this time). Overall, it’s a forgettable video for a forgotten band.

Zombie’s 1998 video for The Ghastly Ones, “HAULIN’ HEARSE”, is one of my two favorites of Zombie’s videos. The song is something like old-school surf rock, so he channels a look that evokes the visual sensibilities of midcentury surf films, albeit with a classic Universal monster movie twist.

The scratchy, grainy film is filmed handheld and entirely in black and white. All the by-now classic Zombie tropes are there: dancing girls, chintzy costumes, and giant masks. “HAULIN’ HEARSE” is the first instance of Zombie’s love for an old-fashioned aesthetic coming into play, giving us a peek into his familiarity with the cinematic language of the horror genre.

By the time 1998 rolled out, White Zombie has disbanded and Rob Zombie was well into his solo act. As such the focus of his videos started shifting squarely towards him. His video for “DRAGULA” depicts him in full-on monster costume, wildly driving a doom buggy with his friends.

The mixed-media approach returns, with Zombie pulling clips from old horror films and utilizing obsolete production techniques like back projection to create an old-fashioned charm. For the first time, his found-footage selections appear to be trying to make some sort of commentary—he juxtaposes 50’s style home movies of families and clowns against atomic bomb explosions.

Dancing burlesque girls make their mandatory appearance, with one of them looking distinctly like Sheri Moon, Zombie’s future wife and frequent collaborator. The style of costuming is also beginning to coagulate into the style seen in HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES, most notably the giant head masks and a menacing robot costume with red goggles for eyes.

Zombie’s “LIVING DEAD GIRL” (1998) is my other favorite of Zombie’s videos. Throughout most of his work, he assembles inspiration from a variety of sources, but here his influence is quite clear: Robert Weine’s silent hallmark of German Expressionism, THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (1920).

Zombie’s approach essentially mimics CALIGARI, right down to the set design. Resembling a scratchy old silent film, Zombie’s reproduction apes the monotone quality of such films—even incorporating the colored tints that filmmakers would apply to evoke mood in the days before color.

Zombie also refrains from moving the camera, opting for locked-off proscenium style shots that further emulate CALIGARI. Sheri Moon, who was by this point Zombie’s cinematic muse and real-life girlfriend, plays the titular “Living Dead Girl”, while Zombie himself plays the Caligari role. “LIVING DEAD GIRL” is standout in that it really shows off Zombie’s deep love and reverence for the genre that continues to inspire him.

Zombie’s “SUPERBEAST” (1999) finds the director really embracing an epileptic style of editing. He’s in full-on camp mode, looking not unlike John Travolta in BATTLEFIELD EARTH (2000) and using heavy filtration and green-screen effects to create his fire and laser backgrounds. The end result is like one of those hypnosis videos on steroids. Sheri shows up here too.

In 2001’s “NEVER GONNA STOP (THE RED RED KROOVY)”, Zombie returns to the 1.85:1 aspect ratio and brings an inherently cinematic quality to his aesthetic. This is understandable, as by this point he had already shot HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES (although it wouldn’t be released for another two years). A strong vision manifests itself here, taking a huge cue from Stanley Kubrick’s A CLOCKWORK ORANGE (1971) in both costumes and set design.

His wide, dynamic compositions are given an added grandiosity with huge crane movements that sweep across the elaborate set. Zombie extends theCLOCKWORK ORANGE conceit to his burlesque dancers. This is arguably his glossiest work to date, containing no scratched film elements or grungy filters.

2001’s “FEEL SO NUMB” finds Zombie using lens flares and bright, lurid colors against a low-key, gritty lighting style. There isn’t a lot to say about this piece other than all of Zombie’s visual signatures (burlesque, costumes, etc.) are present and accounted for.

Very few directors emerge as fully-formed auteurs right out of the gate, and Zombie is certainly no exception. HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES established his filmmaking style to audiences who otherwise wouldn’t be familiar with him, but the striking vision and confidence that marked his debut only came after several years toiling away in the music video realm, where he was free to experiment (wildly) and learn the ropes all at the same time.

HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES (2003)

Judging by its trailers and negative reviews, it was easy to shrug off director Rob Zombie’s film debut, HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES, when it was released in 2003. Lionsgate, the film’s distributor, had a long history of releasing disposable horror fare, so why would a film directed by a largely irrelevant shock rocker from the 90’s be any different?

Granted, a lot of people still hold that opinion, but I find those who sit down to watch Zombie’s work usually come away with at least an admiration for the man’s effort, if not admiration for the work itself. When I was in college, I had heard whispers amongst the various film circles that Zombie was an underrated director, and so one chilly October evening I decided to put the hearsay to the test and popped in the DVD to HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES.

Maybe it was the time of year in which I was watching it, but something about the film immediately trigged a nostalgia center in my brain, and I was immediately drawn into Zombie’s macabre vision. Since then, HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES has become a staple of my yearly Halloween viewing.

Zombie’s directorial debut was originally supposed to be with an installment of THE CROW series named THE CROW 2037. For whatever reason, that film was canned and Zombie found himself free to develop his own material.

He gathered funding from Universal, whom he had a prior relationship with in bringing back their yearly Halloween Horror Nights attraction, and set about the business of shooting the film in 2000 (working with his manager Andy Gould as producer).

Universal’s enthusiasm tempered upon seeing Zombie’s initial cut, and they began to fear that the film would receive an NC-17 rating. To Zombie’s dismay, Universal ultimately pulled the plug. Undeterred, Zombie bought the rights back and shopped the film around town, eventually finding it a home in Lionsgate.

When the film was finally released in 2003, it met with middling success at the box office and some pretty savage reviews, but it did garner Zombie a critic-proof cult following that was strong enough to sustain momentum going into his follow-up.

HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES takes place in 1977-era Texas, where four college students are on a road trip and documenting strange roadside attractions they come across for a book they’re compiling on the subject. After visiting a cheesy museum/haunted house ride dedicated to famous serial killers and run by Captain Spaulding (Sid Haig)—a lively backwoods guy in clown makeup—the kids pick up an obnoxious hitchhiker named Baby (Sheri Moon Zombie).

Shortly afterwards, their car tires blow out, so Baby offers to call them a tow truck. As a torrential rainstorm descends on them, she also offers refuge in her family’s home up the road, which they reluctantly take her up on.

They arrive to find a creepy old house populated by a bevy of strange, off-putting characters: the over-sexed matriarch Mother Firefly (Karen Black), the angry Confederate sympathizer Otis (Bill Moseley) and a mute, deformed giant named Tiny (Matthew McGrory).

Initially dismissive of these perceived “backwoods hicks”, the students get the surprise of a lifetime when they find out they’re actually in the company of a close-knit family of serial killers and necrophiliacs—and they’re the Firefly clan’s next victims.

In the years since his 2003 debut, Zombie has created a reliable repertory of performers he can call upon, and most of his key players (Sig Haig, Bill Moseley, and Sheri Moon Zombie) make their first appearance for him in the film. Haig plays the aforementioned Captain Spaulding, an intimidating and sassy jokester in clown makeup.

Despite his outward repulsiveness, Haig’s characterization is actually quite charming and resulted in his character quickly becoming a fan favorite amongst Zombie’s devoted cult of followers.

The late 70’s indie icon Karen Black uses her unconventional beauty to lend an eerie glamor to the character of Madam Firefly. If anything, her casting shows evidence of Zombie’s familiarity with the deep cuts of 70’s cinema—films like FIVE EASY PIECES (1970) or NASHVILLE (1975).

As Otis, Moseley is all stringy hair and pale complexion, and is easily the most abrasive and menacing presence in the film. Sheri Moon was still Zombie’s girlfriend during the production of HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES, but by the time of the film’s 2003 release she had become his wife.

As Baby, she’s very effective in portraying an obnoxious Harley-Quinn type and taunting our protagonists with that irritating laugh of hers. Other actors of note include a pre-THE OFFICE Rainn Wilson, Tom Towles, and the late Matthew McGrory and Dennis Fimple.

Despite the film boasting two cinematographers in Alex Poppas and Tom Richmond, the look of HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSESis undeniably Zombie’s doing.

Filmed on a hodgepodge of film stocks from 16mm to 35mm (as well as some video), Zombie’s vision evokes the grime of 70’s horror classics like THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE (1974) and THE HILLS HAVE EYES (1977). His lurid color scheme punctuates the inky blackness of the Texas next with bursts of neon and cobalt blue moonlight.

The camerawork makes use of several techniques that were popular in 70’s exploitation, like rack zooms and handheld photography (in addition to classical dolly and crane movements). On his first time at the feature bat, Zombie is already using his camera like a seasoned vet, ably communicating a grand vision with minimal resources.

Several elements of Zombie’s background in music videos manifests in his feature style, such as the use of heavy filtration and damaged film conceits in pursuit of a grungy texture. Continuity largely goes out the window in several sequences, yet it doesn’t hinder the coherency of Zombie’s vision.

For instance, he will dramatically shift the color of a key light with a hard cut (going from white light to red), and while there seems to be no motivation for doing so, it’s curiously effective. The effect is not unlike a cinematic version of a haunted house attraction or ride, which makes the film much more enjoyable than it probably has any right to be.

Zombie also throws in various vignettes that add a music video-style punch, like found footage of burlesque dancers and a recurring “home video” motif where members of the Firefly family break the fourth wall and speak directly to camera, bragging about their murders and taunting their victims. Inspired by similar home movies that the Manson Family supposedly recorded, Zombie shot these vignettes on 16mm film in his basement after principal photography wrapped (and while the film languished on Universal’s shelf).

Being a musician himself, it’s completely understandable that Zombie would have played a role in creating the score. Scott Humphrey is also listed as a composer, and together they create a pulsing, electronic score that recalls the horror films of yesteryear.

Zombie also incorporates a lot of rock music, and while he doesn’t show total restraint in including his own songs, he does make a solid effort to source tracks outside of his own discography. The result is a surprising, eclectic mix that includes The Ramones and that old Marilyn Monroe song, “I Wanna Be Loved By You”.

Perhaps because it was never guaranteed that Zombie would ever get the chance to make another film, HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES is the result of a director literally filmmaking for his life. In other words, he’s throwing all of his directorial conceits into the mix in a wild bid to establish his “style”. While this approach is more or less successful, it earned him just as many detractors as fans.

HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES takes on the form of a macabre circus, using the convenient story device of taking place on Halloween night as an excuse for Zombie to go wild with seasonally appropriate imagery.

This is extended to the opening of the film, which itself is a tribute to those cheesy, black and white horror television programs. In the form of Dr. Wolfenstein’s Creature Feature Show, Zombie absolutely nails the chintzy gothic trappings of a bygone practice whose campiness we don’t get to see much of anymore.

It also points to Zombie’s larger appreciation of classic monster movies like THE WOLFMAN (1941) and FRANKENSTEIN (1931)—the kind of movies that Universal built its studio on.

It’s clear watching HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES that Zombie has studied up on the entire genre of cinematic horror, incorporating nearly every major movement from German Expressionism, to classical gothic, to the shocking visceral-ness of 70’s exploitation. Because he’s so well-versed in the language of the horror genre, he’s able to fuse it all together into something entirely original and make it his stamp.

HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES is not for everyone. On an objective scale, the film—while mostly coherent—is wildly uneven. At least for me, it’s highly enjoyable as a form of cheesy Halloween fun. It’s an instance of a filmmaker taking everything he loves about movies and gleefully putting his own twist on it.

One could even argue Zombie had established himself as something of the Quentin Tarantino of horror: a style marked by strong visual sensibilities, dynamic and original characters blessed with silver tongues, and an eclectic, inspired taste of music. The sum of all its’ Frankenstein-esque parts mish-mashed together translates to a veritable carnival ride of a film.

While it didn’t exactly result in a mainstream breakout for Zombie, HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES gave his bid for a directing career much more credibility.

THE DEVIL’S REJECTS (2005)

When director Rob Zombie made HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES (2003), he put everything he had into it. There was no guarantee he’d ever get to make another movie.

But that didn’t stop him from dreaming about what would happen to his characters after the credits rolled. He began entertaining a wider world for these eccentric creations to inhabit, whereby they would have to answer for the horrible crimes they committed.

When HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES did well enough to warrant another film for the fledgling director, he knew that he wanted to make this sequel as his next picture.

Surprisingly, he took a very different tack than most sequels do. He turned his villains into protagonists on the run, and shifted the tone from horror to a 70’s style road picture. The result was 2005’s THE DEVIL’S REJECTS—arguably Zombie’s best film and a veritable thesis study on his aesthetic.

But more importantly, the film reinforced his reputation as a talented director by selling him to a larger audience and causing many to re-assess any prior prejudices against him.

THE DEVIL’S REJECTS is set six months after HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES, in 1978-era Texas. The Firefly clan is ambushed by a police squadron who have come to make them finally answer for their mass-murderous ways.

The squadron is led by Sheriff Wydell (William Forsythe), the vengeful brother of the cop murdered by Karen Black’s Madam Firefly in the original film. His wrath is utterly biblical, making him out at times to be more psychotic and brutal than the serial killers he aims to eradicate.

After the Firefly family makes an explosive last stand in their decrepit house, the surviving members—Captain Spaulding (Sid Haig), Baby (Sheri Moon Zombie) and Otis (Bill Moseley) go on the run and travel across the Texas deserts to escape Wydell’s persecution. What follows is a road picture along the lines of 70’s exploitation films that brings an unflinching, morally-murky attitude to the proceedings.

Zombie retains most of his original cast from HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES, further establishing his repertory of character actors. Sid Haig graduates from supporting role to lead as Captain Spaulding, the thick-necked jester in clown makeup. Here, he’s revealed as Baby and Otis’ father, and he brings a much more grounded and realistic approach to the character—even going so far as to appear without his iconic face paint for a majority of the film.

Zombie’s wife, Sheri Moon Zombie, reprises her role of Baby, but gone is the annoying brat demeanor and hyena laugh she had in the first film. Here, she’s much tougher and disciplined. Moseley is even nastier and vicious as Otis, now with a full beard and some color regained into his previously-pale skin complexion.

The late Matthew McGrory reprises his role as Tiny, now an even-more grotesquely and disfigured burn victim. He passed away shortly after the film was finished, so THE DEVIL’S REJECTS is dedicated to his memory.

The recently-diseased Karen Black didn’t return to play Madam Firefly due to differences over salary, so the veteran character actress Leslie Easterbrook steps into fill her shoes instead. Easterbrook crafts a normalized version of the character that’s short on camp and long on sexual menace.

THE DEVIL’S REJECTS also contains some new faces for Zombie to focus his lens on. As Sheriff Wydell, William Forsythe is the big bad of the film and, ironically, the one person who is supposed to be the paragon of virtue and justice. His vendetta to avenge his slain brother completely consumes him, turning him into an intimidating and ruthless monster that just might be more brutal and unfeeling than the serial killers he stalks.

Danny Trejo and Diamond Dallas Page play a pair of aging bounty hunters who assist Wydell, albeit with admittedly unconventional tactics. Scream queen PJ Soles makes a brief cameo as Susan, a defiant mother who won’t let Haig’s Spaulding steal her truck without a fight.

And finally, Daniel Lew plays a foul-mouth cowboy hipster, making such an impression on Zombie that he’d come back as a recurring bit player in the director’s later works.

If HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES could be considered a polished studio film, then THE DEVIL’S REJECTS is a downright low-budget exploitation film. The tone switch between these two films necessitated a significant visual overhaul, and cinematographer Phil Parmet ably delivers in his first collaboration with Zombie.

The film was shot on 16mm stock and blown up to 35mm during exhibition in order to give a heightened, yet subtle sense of grit and texture. Zombie and Parmet crank the contrast into overdrive with the bleach-bypass process, crushing the blacks and blowing out the highlights for a sun-bleached look appropriate to the arid desert setting.

Zombie also adds a tinge of blue and green into the shadows via color timing, which gives the image a sickly look and helps to bridge the gap between this film and its predecessor.

Zombie’s gritty, realistic approach to the visuals is reflected in the camerawork—THE DEVIL’S REJECTS is framed almost entirely in handheld close-ups, and largely eschews the wide, dynamic compositions of HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES. However, he does indulge in a few crane and helicopter-mounted shots to add a little bit of grandeur here and there.

Incorporating freeze-frame opening titles (much like Ti West’s HOUSE OF THE DEVIL (2009) does) is the final touch that sells the conceit that this film could’ve actually been made in the time it takes place.

To create the film’s score, Zombie turned to veteran composer Tyler Bates. In Bates, Zombie found a partner that he would continue to collaborate with over the course of several more features. Bates’ discordant score is bombastically propelled forward by heavy percussive elements and dissonant tones.

But the lion’s share of attention to the music goes to Zombie’s inspired needle drops. His selection is much more focused here than it was in HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES, and he even refrains from including his own music.

Instead, he draws from a limited palette of classic 70’s southern rock like Elvis Costello, Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers (along with the chilling Depression-era folk tune “Dark Was The Night”).

THE DEVIL’S REJECTS plays like a thesis statement of Zombie’s aesthetic conceits as a director. He nails an old-fashioned tone that evokes the heyday of 70’s horror, but modernizes it by bringing in mixed media elements and found film footage.

He also utilizes characters from a predominantly blue-collar, “backwoods” background (AKA rednecks). Perhaps Zombie identifies with this very particular subgroup of people more than most, but they undeniably fit inside of his own personal brand: that of a moody, grungy goth rocker popular amongst small-town white youths.

These people are usually the key protagonists in Zombie’s films, albeit filtered through a 70’s time period or some other storytelling mechanism. And as expected, masks, clowns, and other carnival-related imagery all carry strong thematic weight throughout the piece.

One of the most striking things about THE DEVIL’S REJECTS is the fact that there is very little continuity between the film and its predecessor. Despite having the same characters, Zombie has radically shifted away from the macabre carnival/haunted house ride tone of HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES and towards a sun-baked road film vibe.

It’s significantly less comical than the original film, and also less polished, favoring immediacy and realism where HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES favored high production values and theatricality.

Zombie also makes a very bold storytelling decision, in that he challenges the audience to care for a group of sadistic, psychopathic serial killers. On its face, this is a seemingly impossible task; it’s like making a movie where Ted Bundy is the hero.

However, Zombie ably accomplishes this by creating a villain who’s even more sadistic and brutal, someone so inherently unlikeable that he makes the Manson-esque Firefly family look cuddly by comparison.

If anything, the subversive level of engagement Zombie achieves with his audience is arguably the film’s greatest accomplishment.

THE DEVIL’S REJECTS was well-received upon its release, doing better both financially and critically than Zombie’s debut. It even earned a glowing review from an unlikely source: Roger Ebert. Ebert’s endorsement of Zombie’s vision caused the film community to look at him in a different light.

He was no longer a novelty act; he was now a legitimate voice within the medium. Sure, he wasn’t making prestigious award-winning character dramas, but he was making what interested him, and more importantly he was doing it well. THE DEVIL’S REJECTS solidified Zombie’s position as a burgeoning horror director of confidence and vision, and like it or not, he was here to stay.

“FOXY, FOXY” MUSIC VIDEO (2006)

Between the release of THE DEVIL’S REJECTS (2005) and the making of his re-imagining of John Carpenter’s HALLOWEEN in 2007, director Rob Zombie focused on the music side of his career and released a new album called “Educated Horses”. “Educated Horses” featured the single “Foxy, Foxy”, which was selected to become a promotional music video.

Zombie had directed several of the music videos for his own songs in the years prior to his feature debut HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES (2003), so naturally, he was comfortable stepping again behind the camera. “FOXY, FOXY” (2006) is relatively straightforward, presenting nothing new in the realm of the art form.

It’s a performance piece that aims for a modern Woodstock Festival feel, except for the fact that the audience is populated entirely by a gathering of beautiful young hippie women, led by Zombie’s wife Sheri Moon.

The idyllic rural setting is filtered through Zombie’s requisite layer of grunge, manifested in the unwashed, greasy look of the performers and the audience. I’d describe the overall aesthetic as very 1970’s, an old-fashioned look attained through lots of lens flares and shadows that are skewed into a faded green color via post-production grading.

I’ve noticed that Zombie’s music videos in general are very post heavy, with lots of mirror filters, split-screen frames, and snazzy effects. With “FOXY, FOXY” he even switches between 2.35:1 and 1.85:1 aspect ratios with wild abandon. However, all of the visual activity and energy infused via post-production process can’t hide the fact that the video itself is basically an uninspired performance piece.

In terms of Zombie’s growth as a director, there’s not a lot to see here. With “FOXY, FOXY”, he is staying firmly within his comfort zone—not that he needs to go outside it for a piece like this. It’s a low-stakes project as far as I’m concerned, since he didn’t really need to prove his directing skills in this particular instance.

If anything, it was made to sustain his music career first and foremost, and its journey-man-like quality might just have been a result of having to squeeze it in between THE DEVIL’S REJECTS and development of HALLOWEEN.

WEREWOLF WOMEN OF THE SS GRINDHOUSE TRAILER (2007)

By the mid-2000’s, director Rob Zombie had established himself as a formidable voice within the horror genre. I’ve compared Zombie before to Quentin Tarantino—both filmographies share witty, foul-mouthed characters and eclectic musical choices—so it makes perfect sense to me that the two (along with Robert Rodriguez) would collaborate on a project.

In 2007, Tarantino and Rodriguez released GRINDHOUSE, a double-feature nostalgia piece that emulated the 70’s heyday of low-budget exploitation flicks.

The film incorporated a few rather fun conceits, one of which was a series of trailers for fake “upcoming” films that played between the features, each one done by a different director. Some of these trailers would actually become features in their own right (MACHETE (2010) and HOBO WITH A SHOTGUN (2011)).

Zombie’s contribution, the cheesy/gothic WEREWOLF WOMEN OF THE SS, combines two disparate horror archetypes (werewolves and Nazis) in a way that make a weird sort of sense. To realize this morbidly entertaining idea, Zombie calls on his regular group of performers like Tom Towles, Bille Moseley, and wife Sheri Moon Zombie to assume the guise of Nazi officers, scientists and seductresses.

He also brings in a few new, very surprising faces in the form of supreme weirdo Udo Kier and a show-stopping Nicolas Cage as the (suspiciously-Anglo) Chinese sorcerer Fu Manchu.

Because his aesthetic is already so aligned with the grungy, warped texture of Tarantino and Rodriguez’s vision, Zombie doesn’t have to change anything about his visual style. If anything, he only needs to amplify things like film scratches and jitters.

The high production value on display is pushed towards campy fun rather than outright horror.

There’s not a lot to say in regards to Zombie’s growth as a filmmaker—the piece exists mainly as an opportunity to play with his favorite actors while poking fun at both himself and the horror genre in general. WEREWOLF WOMEN OF THE SS is a fun peek into what a Zombie film would look like if blown up to the epic scale that the trailer hints at.

HALLOWEEN (2007)

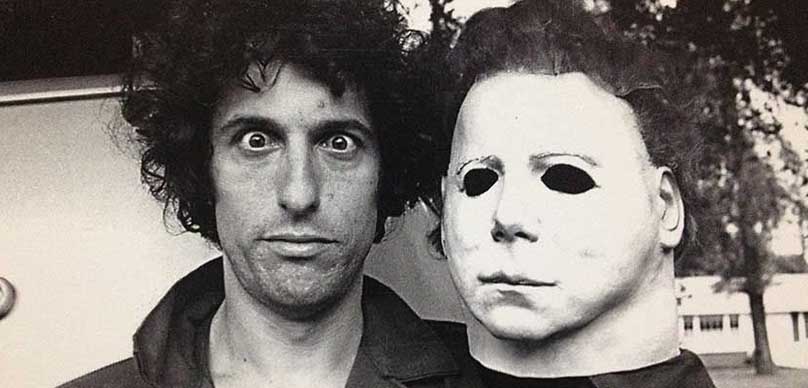

The original HALLOWEEN (1978), directed by John Carpenter, not only redefined the horror genre, but independent film as well. It set the course for the ensuing two decades, giving birth to the slasher subgenre and a veritable rogue’s gallery of boogeymen in Jason, Freddy, Chucky, and Pinhead.

But one name stood above them all: Michael Myers. The serial killer otherwise known as “The Shape” had gone through no less than eight outings by 2007, and by the point the series had become decidedly stale. The success of Christopher Nolan’s BATMAN BEGINS in 2005 proved to studios that audiences would accept, even welcome, old properties that were rebooted for our modern age.

Nolan’s groundbreaking vision for Batman emboldened studios to pursue equally strong-minded directors for high-profile properties in need of creative refreshing. With this in mind, Dimension Films and the Weinstein Brothers courted director Rob Zombie to reboot theHALLOWEEN franchise. Coming off the success of THE DEVIL’S REJECTS (2005), Zombie had previously cited Carpenter’s HALLOWEEN as a key influence in his own aesthetic—naturally, hiring Zombie to breathe new life into a monster that had been left for dead was a no-brainer.

Despite obtaining Carpenter’s blessing (who told Zombie to run with the material and make it his own), the announcement of a HALLOWEEN reboot with Zombie at the helm was met with massive fanboy outrage. As a fan of the series himself, Zombie knew how delicate the situation was, so he approached the shoot with a meticulous eye for detail and a desire to merge his own aesthetic with Carpenter’s iconic story.

Simply put, HALLOWEEN was the biggest film of Zombie’s career, both in scale and stakes. Debuting in the very un-October month of August because some chicken-shit executives didn’t want to open against the reigning, annual SAW franchise and its Halloween-time slot, Rob Zombie’s HALLOWEEN enjoyed a healthy run of success despite its reputation as a controversial, massively un-even film.

Zombie’s HALLOWEEN is split into two distinct narrative halves: the 1970’s and the present day. The 1970’s segment concerns a young Michael Myers (Daeg Faerch) growing up in an abusive household and exhibiting symptoms of mental instability. One day at school, a bully drives him to commit his first murder, and then on Halloween night he butchers his entire family (save for his mother Deborah (Sheri Moon Zombie) and baby sister Boo).

He’s placed in a sanitarium where he languishes for the next fifteen years, visited occasionally by his increasingly-distant mother and a gentle psychiatrist named Dr. Sam Loomis (Malcom McDowell).

As the years go by, he grows into a silent, hulking monster who hides his face behind an array of homemade masks. In the present day segment, Michael finally escapes and returns home to Haddonfield to track down his one remaining family member, Boo—now living a blissfully unaware existence with her foster parents as Laurie Strode (Scout Taylor Compton).

With his reign of terror once again occurring on Halloween night, Michael Myers proceeds to kill everyone who tries to stop him from getting to Laurie. It’s up to Sheriff Brackett (Brad Dourif) and Sam Loomis to stop Myers before he claims the entire town.

Jamie Lee Curtis’ performance in the original HALLOWEEN is a hard act to follow, so newcomer Scout Taylor Compton paints an entirely different portrait of the innocent, virginal Laurie Strode.

If anything, her performance raises an interesting comparison of how teen girls have changed over the course of thirty years—their clothes, sense of humor, open-ness about sexuality, etc.

Compton updates Strode for the new century, giving her an edge while simultaneously making her geekier than Curtis ever was. In the absence of the role’s originator Donald Pleasance, Malcom McDowell is incredibly inspired casting as Dr. Sam Loomis. McDowell’s Loomis is a cold intellectual, prone to fits of ego and theatricality.

He’s less a voice of authority than a thorn in the side of authority. Even those who savaged the movie upon its release generally agreed that McDowell’s performance was one of the highlights. As the iconic Michael Myers, Tyler Mane also has huge shoes to fill. Denied the ability to emote or speak, let alone show his face, Mane instead has to rely on his massive, intimidating frame to convey menace.

To his credit, he does this extremely well, bringing a monstrous quality to Myers while eliminating some of the supernatural spookiness found in earlier incarnations.

As the supporting characters are nowhere near as iconic as Laurie Strode, Michael Myers or Sam Loomis, Zombie is able to safely infuse them with his trademark redneck qualities, especially in his re-definition of the Myers family. As the young Michael, Daeg Faerch is a strange-looking little boy. I can certainly see why he was handpicked to play a future mass murderer.

He’s pretty adept at playing weird and mentally disturbed, so I can’t imagine that his performance won him too many new friends at school. Zombie once again casts his wife, Sheri Moon, in a pivotal role.

Here, she plays Michael’s mother Deborah, essentially a single mother who has to strip to make ends meet. She’s a supporting, nurturing presence for Michael, but even she can’t stop the tragedy that’s coming. In terms of Sheri Moon’s career, HALLOWEEN sees her best performance so far as a tough, conflicted mother.

Another Zombie player, William Forsythe, assumes the role of Ronnie, Deborah’s disabled, deadbeat live-in-boyfriend. As an openly hostile force in the young Michael’s life, his is a murder that’s very well deserved. Danielle Harris plays Annie Brackett, Laurie’s athletic, sarcastic friend. Harris herself is a fixture of the HALLOWEEN franchise, having played Laurie’s daughter in two previous installments.

Brad Dourif plays her father, Sheriff Lee Bracket. Dourif is the under-prepared voice of authority and law in the film, and while he’s a little redneck-y in his own right, he’s got his priorities straight and serves as a great source of conflict given his moral opposition to the Loomis character.

For the most part, Zombie’s repertory of regular performers is relegated to smaller roles and cameos.

Danny Trejo, Lew Temple, Tom Towles, Leslie Easterbrook, Ken Foree and Sid Haig all are present but have severely limited screen time as a result of the story’s already-crowded cast of characters.

Phil Parmet returns to Zombie’s fold as the Director of Photography, giving the 2.35:1 35mm film image a different visual approach for each act. The first act—Michael’s initial wave of murders as a child in the 70’s—is drained of color and light, opting for a handheld, grungy look.

The sanitarium sequences in the second act are mostly static and locked-off, emphasizing the cold, clinical nature of Michael’s surroundings via oppressively symmetrical lines and bright, neutral light.

Zombie often frames the characters in this act as very small within the frame, dwarfed by the immensity of the uncaring institution around them. The third act becomes essentially a remake of the entirety of Carpenter’s original film, with Michael escaping the sanitarium and stalking Laurie Strode back in Haddonfield. These scenes are rendered in a de-saturated, autumnal color palette, as well as in steadicam shots that bring a classical, elegant energy to the piece.

Of course, when the murders start, the film shifts back to the cold, blue handheld compositions we saw in the first act—Michael has come home.

Production Designer Anthony Tremblay does a great job turning Pasadena and Hollywood in the early spring into an autumnal Illinois. It starts with inspired location choices, solidifies with smart set dressing and large amounts of fake leaves and Halloween decorations, and ends in postproduction color grading with Zombie and Parmet draining all of the green from the color spectrum to further sell the autumn vibe.

Returning composer Tyler Bates really had his work cut out for him when it came to creating the score for HALLOWEEN. Carpenter himself created such an iconic suite of cues for the original, in the process making the theme an indispensable seasonal staple. Bates would be damned if he simply replicated the score, and damned if he made it his own at the same time.

He managed to strike a good balance, building upon the iconic theme by giving it a grungier texture through a dissonant, electronic score built from ambient tonal elements. True to form, Zombie also incorporates a lot of 70’s-era needledrops like Blue Oyster Cult’s “Don’t Fear The Reaper” and Nazareth’s “Love Hurts”.

One of my personal musical highlights from the film is when Zombie cheekily includes The Chordettes’ playfully morbid ballad, “Mr. Sandman”.

Zombie just might have been the perfect person to reboot the HALLOWEEN franchise, because the story is a perfect opportunity for him to indulge in all his directorial conceits. The incorporation of Halloween imagery is such a prominent aspect of Zombie’s aesthetic that it’s redundant to even mention it. The instance of young Michael Myers wearing a clown mask to conceal his face is indicative of the carnival imagery he’s drawn from throughout his career.

Going with a low-class “backwoods” characterization for his characters allows Zombie to dress them in long, stringy hair and beards that tend to resemble the director’s own goth rock background. This is a very stark departure from Carpenter’s vision, but contributes to an overall grungy texture.

And finally, Zombie’s love for mixed media manifests in HALLOWEEN as McDowell’s black and white film footage documenting Myers’ childhood development, as well as 8mm home movie footage that Sheri Moon’s character tearfully watches before committing suicide.

Perhaps the biggest controversy surrounding HALLOWEEN was Zombie’s decision to build Myers’ backstory into a significant part of the running time. The original vision of Myers as realized by Carpenter was also known as “The Shape”, a somewhat supernatural, seemingly indestructible entity that could materialize out of nowhere.

He was a relentless killing machine whose terror lied in the fact that his was an evil that was ultimately unknowable. This all had been articulated to me by a friend of mine from my days at Lionsgate, as he worshipped Carpenter’s original and had built his own directorial aspirations with the film as its foundation.

He was infuriated by the idea of a HALLOWEEN remake in general, let alone one that would so radically redefine his favorite character in all of cinema. Many people reacted just as strongly when presented with an inherently human Myers, one who had once been a child like us and was simply a victim of circumstance and mental illness.

They argued that this approach robbed Myers of his terrifying mystique, while others appreciated the extra layer of complexity that Zombie’s take added to the character. Whether or not Zombie’s approach was the right way to go is endlessly debatable, but I’m personally glad this interpretation exists—if only for the sake of exploration.

HALLOWEEN was Zombie’s mainstream breakout, with the storied property delivering his aesthetic to audiences who otherwise would never have been exposed to it. Despite its many flaws, you can’t argue that a lot of hard work and confident vision wasn’t applied in the film’s making.

The release record reflects this via a strong financial performance and equal amounts of critical praise and scorn. By its very design, Rob Zombie’s HALLOWEEN is a deeply divisive film. Ultimately, Zombie was successful because he was able to honor Carpenter’s one request—and however you feel about the film personally, you can’t deny that Zombie didn’t make HALLOWEEN his own.

HALLOWEEN II (2009)

A sequel to Rob Zombie’s re-imagining of HALLOWEEN (2007) was inevitable. The HALLOWEEN series had already seen earlier entries, and Zombie’s efforts were always intended to reboot the franchise for the 21st century. Zombie himself was not interested in doing a sequel, stating that he had said all he had wanted to say with the property via his original film.

When Dimension finally gave the greenlight to HALLOWEEN II in 2009, Zombie found himself in something of a bind—should he pass on the project (and let another director potentially sully his vision?), or take on the job himself and build on the foundations he had previously laid? The directing profession requires a bit of ego, so it’s not a surprise to me that Dimension’s greenlighting of the film prompted Zombie to sign back on in order to protect the sanctity of his vision.

Making a sequel to a remake of a film that itself had spawned several sequels (dizzy yet?) is a tricky proposition. Do you simply re-make the sequel? If you do, you risk falling into the trap of re-making all the subsequent installments. Thankfully, Zombie wasn’t interested in re-making Rick Rosenthal’s 1981 sequel (also called HALLOWEEN II)—instead he saw a way to build out from his original vision.

He was no longer beholden by a reverence for Carpenter’s creation. He was free to make a HALLOWEEN film as if it one had never been made before. But the ability to fully indulge in one’s directorial vision without a system of checks and balances carries its own risks, and in the case of Zombie’s HALLOWEEN II, his excess ultimately derails his efforts.

His gritty, overbearing vision and exploration of Laurie Strode’s shattered psyche, while commendable for not resting on its laurels, led to modest box office, savage reviews, and arguably the highest-profile failure of his film career up to this point.

Much like Rosenthal’s HALLOWEEN II, Zombie picks up right where we left off, with a re-animated Michael Myers (Tyler Mane) tracking Laurie Strode (Scout Taylor Compton) down to the hospital where she’s currently recovering from the events of the first film. But unlike the 1981 sequel, Zombie reveals this all to be an extended dream sequence. In the reality of the narrative, it’s now two years later and Laurie is living with the Brackett family and attempting to move on with her life.

She’s devolved quite noticeably since we saw her last, having adopted a grungy, goth style and lashing out at her friend Annie (Danielle Harris), who she forgets also barely survived Michael’s reign of terror. Laurie is tortured by horrific visions and a general hopelessness that even her psychiatrist can’t help her dig out of.

Meanwhile, Myers has been in seclusion—biding his time until he can return to Haddonfield and find Laurie, his long-lost baby sister. He’s driven by visions of his mother Deborah (Sheri Moon Zombie), who has taken on an ethereal, vengeful form and urges him forward on his unholy quest. Simultaneously, Dr. Sam Loomis (Michael McDowell) has been quite busy, having released a lurid new book about the Myers family.

His success has blinded him to his out-of-control ego and misogyny, and when Michael once again pops up in Haddonfield, he is overcome with a desire to redeem himself and help put a stop to Michael’s killing spree once and for all.

Taylor Compton reprises the role of Laurie, now noticeably traumatized and perhaps resigned to her fate. She’s adopted a goth style of dress, and has forsaken her best friend Annie for a pair of similarly-styled suicide girls from work. This iteration of the character is a much meatier role for Taylor Compton, who completely eschews the cute, geeky demeanor she had in the previous film.

Now, she flails around venomously, sinking even deeper into a pit of despair. This was an interesting writing choice on Zombie’s part to explore the psyche of someone trying to move on after experiencing horrific trauma. How would that change your fundamental character and your outlook on life?

Also reprising his role as Dr. Loomis, Michael McDowell’s character has taken a turn towards the worst. His penchant for indulgence and theatricality has reached its logical zenith: an insatiably egotistical asshole.

He’s gotten rich off exploiting the Myers family tragedy, and it’s blinded him to the hurt he’s causing the survivors. McDowell’s arc is one of redemption, with his tacky, misogynist behavior giving way to a reawakening of conscience upon Michael’s re-emergence.

Tyler Mane also returns as Michael Myers, the silent psychopath and star of the HALLOWEEN series. Rather boldly, Zombie chooses to depict Michael for the majority of the film’s runtime without his iconic mask. Instead, he appears as a giant hobo, complete with full mountain man beard.

He feels much more human in this installment (disregarding his superhuman resistance to things like bullets or shovels, obviously). Zombie’s HALLOWEEN films are strikingly different than any other slasher property out there, because he takes the time to explore the psyche and intentions of his monster.

Zombie’s supporting cast is much more concentrated than it was in the previous HALLOWEEN. Zombie’s wife and most-recurring performer, Sheri Moon, returns as Deborah Myers, but no longer as the caring single mother she once was. In death, she has become an ethereal Lady In White, appearing alongside a white horse and coldly commanding Michael to kill Laurie so their family can be reunited in the afterlife.

As Sheriff Brackett, Brad Dourif is older and wearier, even having let his hair grow out. He’s a little more laid back than he was in the previous film, nearing retirement and old age. His general joviality belies the fact that he has the most to lose from Michael’s re-emergence.

HALLOWEEN series veteran Danielle Harris again returns as Annie, now physically and emotionally scarred from her encounter with Michael. Unlike Laurie, she has largely moved on and is trying to live a normal life. Her sarcastic sense of humor is still intact, but Laurie’s increasing distance from her becomes a source of stress and conflict.

Because Zombie’s focus is scaled down on a small number of characters, he has to go without several of his key repertory players for the first time in his career—actors like Sid Haig, Bill Mosely and Tom Towles have to sit out this round.

Zombie further distances his vision from any associations with Carpenter via the look of HALLOWEEN II, which departs quite noticeably from even its predecessor and easily becomes the most stylized film of the series. Unlike the relative polish of HALLOWEEN’s 35mm anamorphic presentation, HALLOWEEN II revels in amplified grain and darkness via handheld Super 16mm film.

Colors are substantially drained from the picture leaving behind a steely palette of blues, grays, and greens. Even the blood takes on a black, brackish quality. Zombie’s camerawork is inconsistent, veering wildly from handheld closeups to strangely out-of-place aerials shots of Michael walking in the countryside—shots that belong more in THE LORD OF THE RINGS franchise than HALLOWEEN.

Cinematographer Phil Parmet, who has reliably shot Zombie’s work since THE DEVIL’S REJECTS in 2005 is replaced in HALLOWEEN II by newcomer Brandon Trost. As such, Zombie’s shooting style changes ever so slightly.

The picture as a whole is decidedly darker, the violence more brutal and distant. Zombie’s compositions are more considered, shooting through prisms and bars to create visual abstractions in the frame, or shooting into the light to create expressionistic silhouettes and lens flares.

The subplot of Michael having visions of his mother requires Zombie to stray from his gritty aesthetic and convey a surreal dreamscape, which he achieves through bold light, ethereal costumes and heavy color grading. His visual treatment of Haddonfield has also changed, conveying a look that’s much more rustic than the suburbia depicted in the previous film.

This might be due to the fact that the filmmakers shot not in Hollywood and Pasadena, but in rural Georgia to take advantage of its natural, woodsy beauty (and a convenient little tax break).

Tyler Bates returns to score the film, and one of the most notable things about his contribution this time around is the virtual absence of Carpenter’s iconic theme. It doesn’t appear at all until the film’s final scene. The extent of Zombie’s imprint on the film was so pervading that any trace of Carpenter felt off-tone. Every time Zombie and Bates tried to incorporate the classic HALLOWEEN theme, they consistently found that it didn’t work.

Instead, Bates chose to build on the pulsing, ambient electronic sound he developed for the previous film, evolving it into a score that’s very industrial and a-tonal. One of the score’s missteps is a weird choral requiem that happens when we find one of Laurie’s friends dead. It sounds like some cheesy Enya song, unlike anything Zombie would ever allow into his work.

On the source track side of the music, Zombie uses his gifted ear to find some inspired selections. He uses The Moody Blues’ “Nights In White Satin” to chilling effect during the hospital sequence, along with a few other country and punk songs that help to fill out the world of the story.

In the version of the film that I watched (The Director’s Cut), Zombie even incorporates a callback to his first film, ending his story with a haunting, minimalized cover of Nazareth’s “Love Hurts”, and in the process creates an unexpected theme song for the ill-fated Myers family.

I’m not sure what it is about sequels with Zombie, but he has a habit of making his second installments considerably different, and usually grungier, than the originals. He did it with HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES and THE DEVIL’S REJECTS by swapping out the lurid, big-budget 35mm theatricality of the former with the handheld 16mm grit of the latter.

The same goes for his two HALLOWEEN films, with Zombie opting for the lower gauge 16mm film stock to amplify grain and “dirty up” the image. The film is filled with imagery that’s become an indispensable part of his aesthetic: Halloween decorations, masks, carnivals/clowns, rednecks with long greasy hair, neon-bathed strip clubs, burlesque, and mixed media (like the inclusion of a standard-definition VHS clip showing Danielle Harris as a child).

To his credit, Zombie doesn’t approach HALLOWEEN II as a run-of-the-mill horror film. He makes very bold, unconventional choices and distances himself from Michael’s carnage— the kills are consistently seen in wide compositions, or filtered through an abstraction in the foreground.

One memorable kill is a very wide shot that sees Michael appearing literally from out of the blackness of the frame, confidently striding up to a policeman and taking him by surprise.

Zombie even uses Malick-esque cross-cutting and parallel action to layer a kill, letting us hear the bloodcurdling audio while footage of the police descending upon the location plays over it. It’s in the experimental execution and exploration of the horror genre’s cinematic language that Zombie’s approach is most satisfying. It elevates an otherwise middling horror film into something inspired and different.

Zombie could’ve played it safe with a more-conventional approach, and it would have undoubtedly resulted in better numbers and critical reception. However, I have to respect Zombie’s desire to transcend the constraints of the genre and find new ways of expression.

But for all his efforts and best intentions, Zombie ultimately couldn’t transcend a deep-seated ambivalence. Remember that he had never wanted to make sequel in the first place, and he only signed on so it would at least be done on his terms. It’s incredibly hard to supersede a fundamental opposition like that, so whatever inspiration he was able to muster up could only carry the film so far.

In a sense, the film was doomed before a single frame was ever shot. Critics smelled the blood in the water, and they tore it apart. Bad reviews led to diminished box office returns, and HALLOWEEN II went down as Zombie’s biggest failure.

Zombie’s career is still recovering from the blow—his later works have all been low-profile television and indie projects. It’s easy to dismiss HALLOWEEN II, as I had originally done when I first saw it years ago, but watching it in the context of Zombie’s other works, the film’s subtle layers revealed themselves and provide an interesting insight into how Zombie’s approach to film craft has evolved.

THE HAUNTED WORLD OF EL SUPERBEASTO (2009)

While Rob Zombie was working on his film career, he also turned his creative attentions towards a character named El Superbeasto, whom he had previously given life to in comic book form. In 2006, he decided to adapt El Superbeasto’s exploits into an animated feature in the vein of adult-oriented cartoons like REN & STIMPY or SOUTH PARK. Writing and recording it proved easy enough, but the simplistic, cel-drawn animation took an unexpectedly long time.

So long, in fact, that Zombie had to put the project on hold several times to focus on his live-action work. In 2009, the final result of his efforts, THE HAUNTED WORLD OF EL SUPERBEASTO, was quietly released direct to video—and understandably so. It’s easily the worst thing Zombie’s ever done. The oversexed, filthy comedy simply isn’t bold and edgy like SOUTH PARK. Instead, it just feels juvenile and misguided.

El Superbeasto (Tom Papa) is a cocky, over-sexed adult film star and producer by day, vigilante crimefighter by night. That is, he would be if he weren’t so obsessed with getting laid all the time. The current focus of his “admiration” is Velvet Von Black (Rosario Dawson), a sassy stripper who has also drawn the eye of the nebbish fiend Dr. Satan (Paul Giamatti).

Dr. Satan kidnaps Von Black in hopes that she will become his bride, and he can fulfill his destiny as the full-fledged Satan, God Of The Underworld. It’s up to El Superbeasto and his sister/sidekick Suzi X (Sheri Moon Zombie) to venture into Dr. Satan’s lair and retrieve her before he destroys the world.

Zombie’s cast is surprising to me, as it boasts several well-respected actors that you wouldn’t expect to fit into the director’s particular aesthetic. This is evident in Giamatti and Dawson’s presence. Giamatti disguises his voice to an almost-unrecognizable degree and hams it up beyond all restraint. Assuming her best “ghetto queen” demeanor, Dawson’s collaboration with Zombie marks their second time working together—she had had a brief appearance as a nurse in 2005’s THE DEVIL’S REJECTS but was cut out entirely).

It falls to rising comedian Tom Papa to anchor the film as the misogynist luchadore El Superbeasto. Papa may not physically look the part, but that’s the beauty of animation—only your voice has to match. For all the film’s faults, Papa does his best to deliver energy and a dry sense of humor to the proceedings.

The low-profile nature of THE HAUNTED WORLD OF EL SUPERBEASTO means that Zombie gets to fill out the remainder of the cast with his favorite people: Dee Wallace, Ken Foree, Danny Trejo, wife Sheri Moon Zombie, and Bill Moseley and Sid Haig (reprising their characters from HOUSE OF 1000 CORPSES (2003) and THE DEVIL’S REJECTS, albeit in cartoon form).

The medium of animation allows for Zombie to do a stylized, expressionistic riff on his trademark aesthetic. He draws on the bright, colorful style of popular children’s cartoons like SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS or REN & STIMPY, perverting it through the filter of gore, nudity, and other decidedly-adult conventions. Music is provided by Zombie’s regular composer Tyler Bates, who completely phones it in with a forgettable score.

The most memorable aspect of the music lies in Zombie’s hodgepodge of source cues and royalty free classical music (employed for ironic effect given the juvenile depravity on display).

After dabbling in director John Carpenter’s world with his two HALLOWEEN films, Zombie is firmly back within his own universe, populating his fictional world with classic Zombie hallmarks: Halloween masks, costumes, carnivals and clowns, burlesque dancers, and gore. Not only is THE HAUNTED WORLD OF EL SUPERBEASTO highly referential to Zombie’s previous works (Zombie’s classic characters Captain Spaulding, Otis Driftwood and the werewolf Nazis from 2007’s GRINDHOUSE trailer segment are present, amongst others), but it also acknowledges the larger world of horror any chance it gets.

For instance, the film begins with a riff on the classic “audience warning opening of James Whale’s FRANKENSTEIN(1931) and continues on to include several famous faces of horror, like a cameo of HALLOWEEN monster Michael Myers. By taking this tack, Zombie has built a world exclusively inhabited by the monsters and murderers of horror lore—a special world of their own where they can be the normal ones for once.

Overall, I had a pretty unpleasant time watching THE HAUNTED WORLD OF EL SUPERBEASTO. While it’s interesting to see Zombie try something new, and while his decision to try his hand at animation is admirable, his approach proves uninspired and unentertaining. At best, it’s a misguided, indulgent waste of time and money for a story that’s perhaps interesting only to Zombie himself and maybe his closest constituents.

Its low quality is indicative of the downward creative slide that Zombie experienced beginning with 2009’s HALLOWEEN II, and just might be the lowest point of his entire career.

CSI: MIAMI EPISODE: “LA” (2010)

Generic police procedurals like CSI and LAW & ORDER are the bane of my entertainment existence. Their popularity, quite simply, baffles me. I’ve stayed away from CSI MIAMI in particular, mainly because there’s no physical way I can take actor David Caruso seriously. He just seems so self-important and pretentious in return for a minuscule amount of talent.

I can back it up too—my college directing professor recounted a story to us in which on the set for his film that Caruso was in, Caruso was talking shit like a punk and almost got his ass handed to him by Forest Whitaker for the trouble.

Naturally, I was dreading having to watch director Rob Zombie’s episode for CSI MIAMI, “LA”, and my experience in finally doing so validated my preconceptions about the show as a whole. But I certainly came away with questions: why would Zombie be involved in primetime trash like this? Did he desperately need the work? Or worse, did he legitimately like the show?

Objectively, “LA”’s story seems appropriate enough of a fit for Zombie’s sensibilities, given its excursion to Los Angeles and its dealings with the porn industry. Television is a producer’s medium, with a director having to fit into a rigidly established aesthetic in order to maintain continuity across the series. While Zombie tries to buck this by injecting some life and style into the proceedings, “LA” is ultimately just another forgettable episode of a forgettable television show.

The murder of a young call girl has been committed during a swanky Miami hotel’s Halloween party. The suspect is an LA-based porn mogul who had been previously suspected, and ultimately cleared, of killing his wife. Sensing a larger conspiracy, “ace” detective Horatio Caine (Caruso) travels to Los Angeles to dig up evidence that will implicate the mogul and his bodyguard Coop Daley (Michael Marsden) with the murder of the wife and the callgirl, respectively.

And in the process, he just might even clear his colleague’s name. While Caruso was foisted upon Zombie by the nature of his status of the show’s central character, Zombie was able to use his clout to fill out the cast with some of his regulars, like wife Sheri Moon Zombie as a hippie photographer, HALLOWEEN’s Michael McDowell as a droll lawyer, and THE DEVIL’S REJECT’s William Forsythe as a snow-haired, possibly corrupt LA police captain. In a bit of stunt casting, Tarantino regular Michael Marsden plays Coop Daley, the smug bodyguard of the porn mogul.

CSI MIAMI has to be the most garish-looking show on TV. None of this, however, is Zombie’s fault. In attempting to convey a polished, colorful look, the visual team has gone completely overboard with a harsh, overlit lighting scheme and saturation dialed up to the point where the unnatural colors bleed and smear across the image.

Pointless time ramps abound in helicopter shots that try to mimic the work of director Tony Scott. But it’s the camerawork that’s the biggest sin—there’s a constantly-dollying camera tracking left to right and back again like some ADHD yo-yo. It’s easily the most obnoxious way to shoot a scene outside of the (shudder) circular dolly.

The set design is equally laughable, with a generically hi-tech field office that no city or state government in their right mind would ever begin to pay for. I realize this is glossy primetime TV but is it too much to ask for a little bit of realism in our police procedurals?

The episode’s music is one area in which Zombie exerts a little bit of control. Besides the show’s use of The Who for its theme song, Zombie incorporates 70’s folk like The Mamas and The Papas and punk like The Dead Kennedys to add a little bit of California flavor. However, since this is primetime TV for idiots, he has to dumb down his selection and go with source cues that are way too on-the-nose (“California Dreamin”, and “California Uber Alles”).

Zombie’s presence mainly manifests itself through the set design, which is full of the imagery that he has built his career on: Halloween decorations, burlesque and a general carnival atmosphere during the opening costume party, and homages to classic horror in the form of F.W. Murnau’s silent masterpiece NOSFERATU (1922) projected onto a screen in the hotel room where the murder occurs.

Thematically, Zombie’s preoccupation with the culture surrounding porn is evident in the main suspect being a sleazy pornographer.

As Zombie’s first foray into episodic television, “LA” seems to be a bid for mainstream relevance. It’s the same kind of stunt directing that the mainline CSI series previously employed in 2005 when it hired Quentin Tarantino for its pair of “GRAVE DANGER” episodes. Television isn’t a great forum to mount a comeback bid when your career is slumping, but at the very least it’s interesting that Zombie was compelled to try out other directing mediums to expand the scope of his craft.

COMMERCIALS (2011-2012)

By 2011, director Rob Zombie was gearing up for his return to feature films. In the meantime, he turned his attention towards a potential side-career in the commercial sector—a reliable, lucrative scenario for the right person. Commercials are a relatively anonymous medium, where the director has to forsake his or her aesthetic in order to convey a given brand’s character and image. Since Zombie’s aesthetic is so well-defined, one can see how he’d be a tough sell to ad agencies. Ironically, it was the agencies that sought him out so he could replicate his style for them.

WOOLITE: “TORTURE” (2011)

Zombie’s first commercial was for detergent brand Woolite, with the conceit being: what does it look like when Leatherface from THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE does his laundry? Understandably, he’d be a complete psycho about it, so “logically”, he needed some heavy duty detergent.

Zombie creates a grungy, old-fashioned vibe that steals from that seminal 70’s horror classic as well as some of the new standard-bearers of the recent “torture porn” craze like SAW (2004) or HOSTEL (2005). As a first commercial, “TORTURE” is pretty effective and entertaining. For a mild-mannered detergent brand, the concept is pretty out there.

AMDRO CAMPAIGN: “DEATH NOTE”, “DARK ROOM”, & “THE ANTS GO MARCHING” (2012)

In 2012, Zombie created a three-spot campaign for the bug-killing spray Amdro. All three spots follow the same conceit, with a crazed maniac sitting in a basement, putting together a master plan of devious concoctions and murderous treachery—only to reveal that it’s all so he/she can kill the bugs infesting his/her suburban lawns.

The spots are lit in a low-key noir style, with lurid colored lights adding to the grungy basement vibe. Zombie also employs several jump cuts to convey a twisted, shattered psyche. “DEATH NOTE” in particular is notable for the casting of Clint Howard, who has appeared in several Zombie films previously.

Zombie’s commercial work is intriguing for the very notion that he uses his uncompromising visual style for comedic effect. These four spots are indicative of a rejuvenated Zombie, more energetic than he’s been in quite some time. To me, it seems that Zombie is beginning to shake out of his funk at this point, entering into a leaner, more inspired phase of his career.

THE LORDS OF SALEM (2012)

The disappointing reception of 2009’s HALLOWEEN II was a real setback for director Rob Zombie’s career. While he was working (harder than usual) to get his next film off the ground, Zombie diversified into several other formats, like episodic television and stand up comedy specials. All the while, his off-days were spent in the lab, tinkering away at his next feature project: THE LORDS OF SALEM (2012).

His reputation was tarnished by HALLOWEEN II’s failure, so he had to look to the independent sector for his next film, meaning he needed to do more with less. Towards this end, he enlisted the help of cutting-edge horror producers, Jason Blum and Oren Peli, who had previously shepherded PARANORMAL ACTIVITY(2007) and INSIDIOUS (2010) to significant success.

Zombie was well-aware that his next project came with high stakes, which translated to a scaled-down, focused approach. All the ingredients were ripe for Zombie to mount a textbook comeback.

THE LORDS OF SALEM takes place in the infamous, eponymous Massachusetts town, a place rich with folklore about the supernatural. Heidi Hawthorne (Sheri Moon Zombie) is a dreadlocked ex-addict, a late night radio DJ, and a descendant of Reverend Hawthorne: the man who put a coven of alleged witches to death during the Witch Trials. Unbeknownst to her, the head of the coven—a nasty witch named Margaret Morgan (Meg Foster)—has put a curse on Hawthorne’s bloodline.

One day, Heidi receives a mysterious box at the radio station where she works. It contains an unlabeled record that, when played, lets loose a wave of unearthly and demonic music. Heidi soon becomes haunted by the music, affected to such a fundamental degree that she slowly withdraws from the world.

As horrifying supernatural visions plague her into relapsing with her drug use, it becomes increasingly clear that she’s a player in a larger plan that’s been centuries in the making- a plan that will require her to bear the Antichrist.

Zombie has always put his wife Sheri Moon in his work, but THE LORDS OF SALEM is the first instance where she’s front and center, and carrying the entire film by herself. The role of Heidi is a far cry from the previous roles she’s played for Zombie, requiring her to be bookish and quiet while still possessing the director’s requisite grunge.

She’s been tattooed to high heaven, each piece of ink becoming a visual signifier of her drug-fueled past. In terms of her entire career, this is probably Sheri Moon’s most compelling performance. Meg Foster plays Margeret Morgan, the evil head of the witch coven. She turns in a fearless performance that requires her to contort her face into nasty expressions and appear totally nude—a courageous choice on her part considering her age.

Bruce Davison plays Francis Matthias, a writer and local authority on Salem’s witch history. He’s kindly and mellow, like a sedate version of HALLOWEEN’s Dr. Loomis, with both serving as a source of exposition and investigation. Davison’s performance brings a warm, paternal presence to the film, lulling us into a false sense of comfort and security before it’s cruelly ripped away.

Jeff Daniel Phillips, a bit role character performer who previously cameo’d in Zombie’s HALLOWEEN II graduates to full-on supporting role as Whitey, a fellow radio DJ and Heidi’s best friend. Gloriously bearded and sufficiently sarcastic, Philips is convincing as a burnt-out townie who doesn’t care about anything except his friends.

Ken Foree, a regular in Zombie’s repertory, plays Herman Jackson, a third radio DJ with a smooth and silky voice. If you’re at all familiar with Foree’s other work, you’d know that the role isn’t a stretch for him whatsoever. Horror film icon Dee Wallace plays Sonny, a witch disguised in the form of a wine-guzzling self-help guru. This is her second performance for Zombie, in addition to her second performance in a modern-day “satanic panic” film after appearing for director Ti West in his 2009 film THE HOUSE OF THE DEVIL.

Another Zombie regular, Sid Haig, purportedly had a cameo in the film, but his part was ultimately cut—a decision indicative of the director’s newfound discipline and restraint.

HALLOWEEN II’s Brandon Trost returns as the cinematographer, helping Zombie transition from traditional celluloid film to digital photography in the form of the Red Camera. Despite its digital origins, THE LORDS OF SALEM ably replicates the aesthetic of film, as well as Zombie’s grainy, dark, and oppressively grungy style.

The added flexibility to manipulate the image that’s part and parcel of digital acquisition allows Zombie and Trost to give the film a uniquely lurid look—the colors are nearly bled out of the frame, save for bright splashes of red, and the highlights bloom in a way that’s reminiscent of Janusz Kaminski’s work. Zombie’s camera-work is reserved and deliberate, incorporating a mix of long, slow dollies and locked-off static shots to tell the story.

The film is at its most unsettling in the vortex that is the hallway of Heidi’s apartment complex. Production Designer Jennifer Spence finds the perfect wallpaper and plasters it all over the walls to create an irresistibly foreboding feel. The result is a slow, creeping dread that’s eerily reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s THE SHINING (1980).

Musically, THE LORDS OF SALEM is a huge departure in Zombie’s work, mostly because it doesn’t feature the participation of musician Tyler Bates. Instead, Zombie enlists the help of Griffin Boice and John 5 to create an unsettling, pulsing score—an electronic texture punctuated with the haunting melancholy of piano chords.

They’re also responsible for the titular vinyl record that Heidi receives, sounding every bit as ungodly as you would expect a satanic record to sound. Zombie utilizes a variety of different source cues, veering from old rock, to soul, to choral classical music and back again. He makes great use of Velvet Underground’s “Venus In Furs”—an obvious bid to redefine our perceptions of the song and make us forever associate THE LORDS OF SALEM with it.

However, his attempt falls short in light of the fact that Gus Van Sant used the same song to much more striking effect in his 2005 film LAST DAYS.

As I wrote before, Zombie’s direction is much more restrained and patient than his previous work. He shows true confidence in that he doesn’t use flashy camerawork or over-stylized visuals to create a compelling, disturbing experience. His old-fashioned aesthetic is informed by the subgenre of “satanic panic” horror films that came out in the 1980’s—a niche that similarly influenced West’s HOUSE OF THE DEVIL (the two films exist in my mind as sister projects, despite being totally unrelated to one another).

Despite the major deviation from his previous aesthetic, several of Zombie’s aesthetic hallmarks remain: lurid neon, Halloween makeup/costumes, and countless references to film history (Heidi has the iconic image of the moon with a bullet in its eye from George Melies’ pioneering silent film A TRIP TO THE MOON (1902) plastered as a giant mural across her bedroom wall).

THE LORDS OF SALEM is a noticeably personal film for Zombie. Besides taking place in his home state of Massachusetts– not far from the town he grew up in– the film’s indie sensibilities point to a strong passion on Zombie’s part to bring the film into the world. However, due to the film’s limited release, THE LORDS OF SALEM was hampered from attaining its true potential. It’s garnered something of a small cult status in the wake of its release, and I wouldn’t be surprised if that cult grows larger over time.