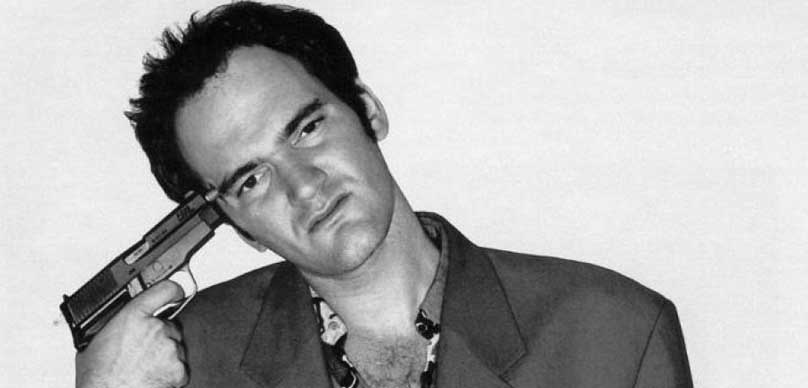

In terms of American independent film, there is Before RESERVOIR DOGS (1992), and After RESERVOR DOGS. Director Quentin Tarantino’s feature debut was a truly paradigm-shattering event, single-handedly turning a sleepy Utah ski town into something of a promised land for aspiring filmmakers the world over. No one quite knew what to make of its razor-sharp wit and unflinching violence, but they knew that a forceful new voice had just descended with a vengeance on the complacent Hollywood system. It’s hard not to speak in hyperbolic terms when discussing Tarantino—the man’s style and subject matter practically begs for it.

RESERVOIR DOGS has often been voted as one of, if not the best independent films of all time. As a hard-boiled gangster/crime picture, it wears its influences on its sleeve, but then proceeds to upend every expectation in the book like a bull in a china shop. Despite multiple viewings, it will still grip its audiences with gritted teeth and clenched knuckles like it did the first time.

I was a senior in high school when I familiarized myself with Tarantino, having casually heard how PULP FICTION (1994) was such an incredible film throughout my life. It wasn’t until I watched my first Tarantino film, 2004’s KILL BILL VOLUME 1 in theaters that I was compelled to visit his back catalog. On a whim, I snatched up both DVDs of PULP FICTION and RESERVOIR DOGS, with only the faintest idea of what I was getting myself into.

While his later films would sprawl out to broader scales, RESERVOIR DOGS tells a very tight, very compact story that could easily be translated into live theatre (and has, on multiple occasions). Five common criminals team up to stage a simple diamond heist, only for it to go horribly wrong. The dazed and confused criminals rendezvous in an industrial warehouse on the fringes of town, trying to make sense of what happened. As they argue and debate amongst themselves, they slowly realize that there’s a rat, or worse—an undercover cop—in their midst. But figuring out the identity of the rat won’t be so easy, with tempers flaring and unexpected loyalty defections that raise the stakes to Shakespearean proportions.

You can read all of Quentin Tarantino’s Screenplays here.

Tarantino got his break off of RESERVOIR DOGS simply by the strength of his crackerjack script. Through some personal connections, the screenplay winded up in the hands of character actor and frequent Martin Scorsese collaborator, Harvey Keitel. Upon reading Tarantino’s script, Keitel immediately called up the young aspiring director and asked to take part in it. Keitel’s participation proved instrumental, bringing in $1.5 million in financing and serious name recognition for a film that Tarantino had initially envisioned shooting with his friends for $30,000. Coupled with the opportunity to workshop his script in-depth at the Sundance Institute’s Directing Labs, Tarantino was able to come to set on the first day with all the tools he needed to deliver a knockout film.

Tarantino has always had an impeccable eye for casting, and the ensemble he collected for RESERVOIR DOGS is filled with unconventional, yet incredibly inspired choices. The aforementioned Mr. Keitel experienced a late-career resurgence as a result of his performance as Mr. White, the tough yet tender thug at the center of the story. Tim Roth, as Mr. Orange, is convincing as both a dangerous criminal and a cocky undercover cop. Roth’s performance is superlatively dynamic despite spending the majority of his screen time lying in a pool of blood.

Michael Madsen plays one of the film’s most terrifying characters, a smooth and squinty-eyed career criminal with a volatile sadistic streak—Mr. Blonde, real name Vic Vega. Madsen’s too-cool-for-school performance results in a simple torture sequence becoming one of cinema’s most profoundly disturbing moments. Mr. Blonde is a sick fuck, taking great pleasure in torturing a cop by cutting off his ear and soaking him in gasoline, only for his own amusement.

Steve Buscemi plays Mr. Pink, a squirrelly, self-deluded member of the team. Tarantino initially wanted to play the part of Mr. Pink, but Buscemi’s energetic, bug-eyed audition convinced him otherwise. Buscemi’s performance is incredibly memorable, with his argument for why he doesn’t tip waitresses in the opening diner scene being one of the most iconic moments in the movie. Veteran character actor Lawrence Tierney plays the gang’s curmudgeonly fat-cat boss, Joe Cabot, with a tough, yet paternal flair. Rounding out the cast is the late Chris Penn as Nice Guy Eddie, Joe Cabot’s vindictive rich-prick son.

As Tarantino’s first, true professional work, RESERVOIR DOGS looks slick and polished, with none of the amateur-looking roughness that plagued his first attempt, MY BEST FRIEND’S BIRTHDAY (1987). The first film to be produced with his frequent production partner, Lawrence Bender, RESERVOIR DOGS puts every cent of its $1.5 million budget on the screen. For his first time working with 35mm film, Tarantino chooses the inherently-cinematic 2.35:1 aspect ratio to create dynamic wide compositions and infuse the maximum amount of style. Cinematographer Andrjez Sekula gives the film a mid-80’s Technicolor patina comprised of washed out colors to complement Tarantino’s “Valley burnout” aesthetic. The muted color palette also makes the bold splashes of crimson blood all the more jarring and visceral.

I’ve written before about how Tarantino educated himself on filmmaking primarily by the voracious consumption of films, so it’s interesting to see how he uses the camera when he has the financial resources to be creative. For the most part, RESERVOIR DOGS assumes a somewhat formalist style, preferring wide compositions and deliberate, smooth dolly movements. This is interspersed with jarring handheld work, especially in the use of long tracking shots—a technique that would later become one component of Tarantino’s signature style. For instance, there’s a moment halfway through the film when Mr. Blonde interrupts the torture of his captive to retrieve a gas can from his car outside. The camera follows Michael Madsen as he steps outside, grabs the canister, and returns inside in one continuous shot. While admittedly simple visually, this technique is incredibly complicated to pull off in one long take—there’s exposure switches and focus pulling to worry about, not to mention the fact that film is designed in two different color temperatures (daylight and interior), and can’t exactly be switched out mid-take. Techniques like this require a competent, steady hand that fundamentally understands the nature of film-based acquisition. RESERVOIR DOGS is full of these understated, incredibly complicated visual flourishes. For a first-time director with no formal film education to effortlessly do this time and time again, with style and grace to boot, is truly an astonishing thing to behold.

Tarantino’s mastery of the craft on his first time at bat also extends to the film’s sonic aspects, specifically the music. The director eschewed the use of a conventional composer or score, opting instead to create a rockabilly musical landscape of old 70’s rock songs. This conceit is incorporated into his self-contained universe, as the broadcast content of Tarantino’s fictional, recurring radio station K-Billy. Tarantino’s eclectic taste in music is responsible for perhaps the film’s most infamous, enduring scene—who can easily forget the uneasy juxtaposition of watching a man’s ear hacked off while the jaunty rhythm of Stealer Wheel’s “Stuck In The Middle With You” bounces along the soundtrack? As a developing filmmaker myself, Tarantino was a huge influence in the sense that his style exposed the unlimited possibilities of inspired and unexpected musical selections.

RESERVOIR DOGS put Tarantino’s bold, take-no-prisoners style on the map. It suddenly became very cool in mainstream entertainment to find creative combinations of wit and profanity, to play up violence to an almost-cartoonish degree, or to make left-field pop culture references. When Tarantino used his crucial opening minutes to ramble at length about the true meaning of Madonna’s song, “Like A Virgin”, he jumpstarted the era of self-referential pop culture that gave us the likes of Joss Whedon and Wes Craven’s SCREAM (1996). As an interesting little aside, the characters mention Pam Grier at one point, who would later go on to start for Tarantino in his third feature, JACKIE BROWN (1997).

Other elements of Tarantino’s distinct style make their first appearance here in his filmography. He incorporates a nonlinear storytelling structure, a chronological conceit that withholds key information for maximum dramatic impact, courtesy of Tarantino’s most valuable collaborator: the late editor Sally Menke. His penchant for twisting his characters’ motivations into Mexican Standoff scenarios manifests itself quite literally in the climax of RESERVOIR DOGS, an occurrence that accurately reflects the uncertain loyalties and hidden intentions of its characters. Other, lesser Tarantino-esque tropes also pop up throughout, like extended sequences set in bathrooms or diners.

Tarantino, along with Generation X contemporary Kevin Smith, were two of Sundance’s first high-profile breakout filmmakers. RESERVOIR DOGS was a game-changing picture, with its release launching the career of one of cinema’s most audacious, divisive characters. All those years of watching countless films, hacking away at his old scripts, and good-old-fashioned networking had finally coalesced into a directorial style that was comprised of everything that came before it, yet completely unlike anything that had ever been seen.

Sponsored by: Special.tv – Stream Independent

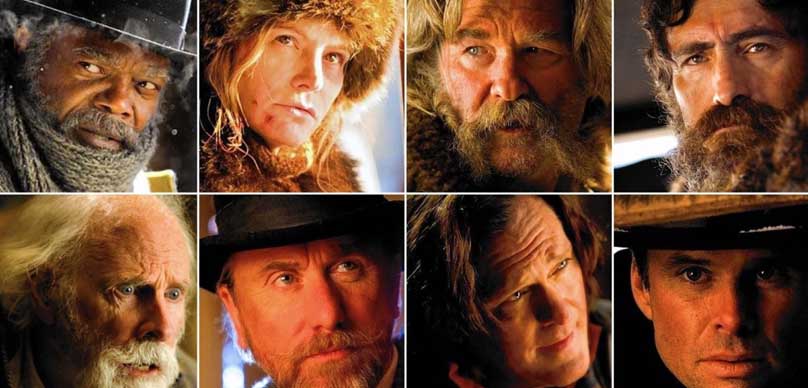

Another aspect of this period in Tarantino’s career has been the huge critical and financial success of his work. After a long awards-circuit dry spell, INGLORIOUS BASTERDS marked Tarantino’s return to the Oscar shortlist– a return he cemented with the even-larger success of DJANGO UNCHAINED and its subsequent win for Best Original Screenplay. THE HATEFUL EIGHT was similarly praised, earning mostly-positive reviews that noted his continued excellence in both writing and direction. The film grossed $155 million against its $44 million budget– a notable downturn in the recent trend, but far from his worst showing.

Another aspect of this period in Tarantino’s career has been the huge critical and financial success of his work. After a long awards-circuit dry spell, INGLORIOUS BASTERDS marked Tarantino’s return to the Oscar shortlist– a return he cemented with the even-larger success of DJANGO UNCHAINED and its subsequent win for Best Original Screenplay. THE HATEFUL EIGHT was similarly praised, earning mostly-positive reviews that noted his continued excellence in both writing and direction. The film grossed $155 million against its $44 million budget– a notable downturn in the recent trend, but far from his worst showing.