Sometime after the runaway success of 2012’s DJANGO UNCHAINED, director Quentin Tarantino was taking in a viewing of John Carpenter’s horror classic, THE THING (1982). He came away from this particular screening with complicated feelings– an impression that compelled him to take to his writing as a way to process his reaction. The idea that would eventually become his eighth feature film, 2015’s THE HATEFUL EIGHT, was initially envisioned as a novel he called “Django In White Hell”, a sequel of sorts to his previous film.

Naturally, a director with as feverish a cult following as Tarantino’s is going to be the subject of intense scrutiny during the creation of a new project; somehow, an early draft (complete with his signature hand-scrawled title page) leaked to the internet and was widely circulated amongst the filmgoing public. A despondent Tarantino hastily announced he was canceling any further development of the film in light of the leak, but after a warmly-received live table read at the Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, he was ultimately persuaded to continue forward with the project.

Read Quentin’s Screenplay for This Film Here

Having dropped the “Django sequel” aspect early on in the writing process, Tarantino structures THE HATEFUL EIGHT as a chamber piece in the vein of his 1992 debut, RESERVOIR DOGS— albeit filtered through the prism of a harsh Wyoming winter in the post-Civil War era. He began with a basic premise: what would happen if you stuffed eight hateful and untrustworthy miscreants into a room and slowly started turning them against each other? The answer, obviously, is a total bloodbath.

Though the film’s shoot in Telluride, CO during an unseasonably warm and pleasant winter might suggest otherwise (1), the story finds a monstrous blizzard forcing several shady and unpredictable characters to seek shelter at Minnie’s Haberdashery, a rustic cabin in the woods outside of the fictional town of Red Rock.

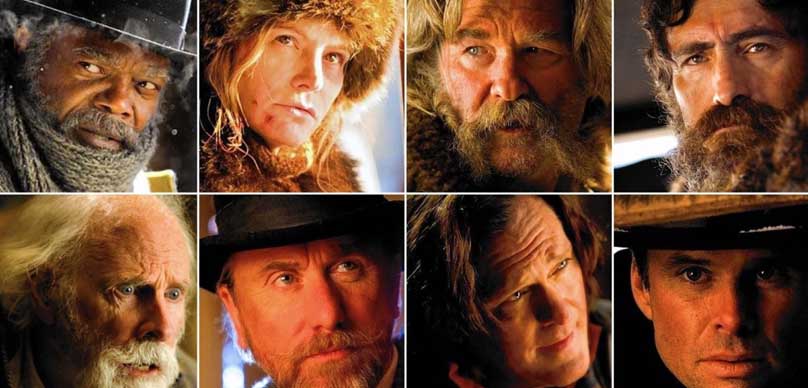

A perennial Tarantino repertory player since 1994’s PULP FICTION, Samuel L. Jackson is finally given top billing for his performance as Major Marquis Warren– a taunting and tempestuous bounty hunter whose journey to Red Rock is cut short when he’s stranded out in the middle of the storm. He hitches a ride to Minnie’s with an old acquaintance and fellow bounty hunter, John Ruth The Hangman, played by Kurt Russell in his second collaboration with Tarantino after 2007’s DEATH PROOF. Russell enthusiastically hams it up with his best John Wayne impression, turning in a performance that, in any other director’s hands, would steal the show at every juncture.

But this isn’t any other director’s film– it’s Tarantino’s, and both Jackson and Russell have stiff competition in the gallery of murderous rogues drawing ever closer around them. The remainder of the titular gang of disdainful scoundrels is comprised of the likes of Jennifer Jason Leigh, Bruce Dern, Demian Bichir, and longtime Tarantino players Tim Roth, Walter Goggins, and Michael Madsen.

Leigh was nominated for a Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance as Daisy Domergue, the stubborn and vicious prisoner chained to John Ruth’s hip. As the ringleader of a roving gang of bandits, Leigh’s devious presence unifies this seemingly-random assortment of killer oddballs into something resembling a cohesive conspiracy that plots to free her from the clutches of The Hangman.

Fresh off the heat from his acclaimed turn in Alexander Payne’s NEBRASKA (2013), Bruce Dern gets to spend the entire shoot reclining in a cushy chair in his role as a cranky Confederate general named Sandy Smithers. Initially, a happenstance visitor at the Haberdashery, Smithers’ personal history is found to be intermingled with the other guests in surprising fashion, but none more so than his “intimate” connection to Major Warren– the man who murdered his son. Also seemingly thereby total coincidence, Roth, Madsen, and Bichir’s characters are revealed to be members of Domergue’s gang; Roth being the well-dressed executioner with a British accent, Oswaldo Mobray; Madsen being a gruff and reclusive cowboy named Joe Gage; and Bichir being the squinting ranch-hand, Mexican Bob.

After a minor supporting turn in DJANGO UNCHAINED, Goggins receives an increase in screen-time with his role as the goofy hayseed Sheriff-elect of Red Rock, Chris Mannix. His folksy drawl helps sell his background as a Confederate rebel, an affiliation that initially aligns him with Dern’s General Smithers before forging an unlikely alliance with the person who by all accounts should be his mortal enemy, Major Warren.

Tarantino’s cast is slightly larger than the eight advertised on the marquee, incorporating James Parks (son of another Tarantino regular, Michael Parks) as an irritable cart driver named O.B, DEATH PROOF’s Zoe Bell as a bubbly frontier Kiwi named Six Horse Judy, and Channing Tatum as the rakish Francophile bandit (and Daisy’s brother), Jody, amongst others. Tarantino engineers his films entirely around the interactions of these characters, strategically employing surprise revelations and backstabbing double-crosses to ratchet up the tension until it explodes in grandiose, bloody fashion.

Tarantino initially broke out on the strength of his unique voice as a screenwriter– a voice that fueled highly-identifiable energy and visual style. As his voice has matured, his aesthetic has mellowed out; relying less on kitsch and pop flash and more on beautiful, technically-accomplished cinematography. This shift began in earnest with 2009’s INGLORIOUS BASTERDS and continues with THE HATEFUL EIGHT by retaining Tarantino’s regular cinematographer Robert Richardson.

The affected retro vibe of his earlier work feels uniquely organic here, owing to the fact that Tarantino and Richardson shot the film in the Ultra Panavision 70mm format– the first film to do so in fifty years. The decision to utilize an otherwise-extinct format subsequently informed every technical decision down the line. Shooting on 65mm film stock that would later be projected in 70mm, THE HATEFUL EIGHT boasts an ultra-wide 2.76:1 aspect ratio (the widest around). Tarantino’s compositions and camera movement are tailored accordingly, framed into a wider panorama to compensate for the snow-capped vistas that tower in the distance behind Minnie’s Haberdashery.

Majestic crane and dolly movements appropriately evoke the sweeping scope of westerns past while also enabling modern stylistic conceits like split-focus diopter compositions, slow-motion bullets that hit home with the sonic force of bombs, and Tarantino’s own signature low-angle POV shots.

Tarantino’s old-school approach continued on to the film’s post-production. While 35mm prints for the shorter theatrical version were struck from a digital intermediate, Tarantino specifically avoided the D.I. suite when it came time to color the 70mm Roadshow version, which means the cold blue exteriors, warm amber interiors, and the rich hues of the period costumes are the result of organic photochemical color-timing.

THE HATEFUL EIGHT also marks Tarantino’s second consecutive collaboration with editor Fred Raskin, who stepped in to replace Tarantino’s longtime cutter Sally Menke after her unexpected death in 2010. Raskin proves an invaluable ally in helping Tarantino achieve the unique retro flavor of the bygone “roadshow” presentation format.

A staple of midcentury American cinema, the “roadshow” is a term typically ascribed to 3 hour+ epics that adopted a presentation style not unlike stage performance, complete with an orchestral overture and intermission. Whether its due to dwindling audience attention spans or a desire to cram more screenings into a single evening, the roadshow has long fallen out of fashion. The last high-profile roadshow presentation was relatively recent, for Steven Soderbergh’s s CHE (2008) — a sprawling, 4 hour portrait of the eponymous revolutionary fighter — but even then, it was regarded as a once-in-a-lifetime anomaly.

The 187-minute 70mm roadshow presentation, containing an overture, intermission, alternate footage and six minutes of extra footage over its shorter 35mm sibling, is Tarantino’s preferred version of THE HATEFUL EIGHT— yet it’s also the least-seen. Tarantino and his producers (Stacey Sher, Shannon McIntosh, Richard N. Gladstein, and longtime collaborators Harvey and Bob Weinstein) knew that the considerable cost (reportedly $8-10 million) to retrofit enough theaters with analog 70mm projectors capable of handling over 250 pounds worth of film reels was going to be an extremely limiting factor in distributing Tarantino’s intended vision (1).

Instead of simply giving in to the realities of the market, however, they aggressively pushed to install the necessary equipment in 50 theaters around the world while promoting the roadshow version as a special, must-see limited engagement. The 35mm version saw a much wider circulation, and as of this writing is currently the only version of THE HATEFUL EIGHT available on home video. However, Tarantino does manage to nod towards his preferred vision within the 35mm cut by using the occasion of his opening credits to allude to an informal overture via a long, glacially-paced shot that allows the music to take prominence.

In addition to THE HATEFUL EIGHT’s considerable technical innovations, the film also marks Tarantino’s first time using a wholly-original score, courtesy of legendary spaghetti western composer Ennio Morricone. A longtime idol of Tarantino’s, Morricone had lent some pre-recorded cues to the director for use in THE DJANGO UNCHAINED, only to publicly express his displeasure at how his music was handled and vow to never work with the provocative auteur again (1). Morricone obviously changed his mind somewhere along the way, as THE HATEFUL EIGHT boasts a suite of new cues that would land the venerated composer his first-ever Academy Award.

Combining a grandiose, lumbering new sound with a few of his unused cues from THE THING, Morricone’s score benefits from the total creative freedom afforded him by Tarantino. This being a Tarantino film, however, THE HATEFUL EIGHT would be remiss not to include a few choices, anachronistic needle drops (and to drop them just as suddenly in transitioning to a new scene). Towards this end, Tarantino incorporates an inspired mix of tracks from the likes of Jack White and Roy Orbison and even throws in a poignant piano rendition of “Silent Night” to hammer home the film’s Christmas-time setting.

There are few voices in cinema as singular as Tarantino’s, each of his films proudly bearing his unique stamp. THE HATEFUL EIGHT is undoubtedly a piece with Tarantino’s efforts to expand his interconnected cinematic universe while simultaneously drawing it closer together (see the surprise revelation that Roth’s character is actually an ancestor of Michael Fassbender’s Lt. Archie Hicox from INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS, or Madsen’s musings that “a bastard’s work is never done”, also from the 2009 film).

Like his previous films, THE HATEFUL EIGHT is structured in his distinct format– self-contained sequences that are partitioned off into book-style chapter intertitles yet presented in a nonlinear fashion as a means to bring further illumination and context to previous events. Within the story itself, his characters are gifted with an almost metatextual awareness about the greater universe around them. They seem to know they are inside a Tarantino film, readily breaking the 4th wall as if acknowledging their shared creator. Indeed, Tarantino himself is often a character in his own films, deploying himself into a range of capacities from full-fledged characters (RESERVOIR DOGS, PULP FICTION), to cameos (DEATH PROOF, DJANGO UNCHAINED), and even as an omniscient narrator, as seen in THE HATEFUL EIGHT during the feverish “Domergue’s Got A Secret” sequence. The characters within THE HATEFUL EIGHT— like Tarantino’s other iconic creations dating all the way back to RESERVOIR DOGS— all possess a sharp wit, a profanely florid speaking prose, and a gleeful eagerness for borderline-sadistic violence against their fellow man.

Tarantino has always worn his B-movie influences on his sleeve, and the trajectory of his career has seemingly organized his favorite genres into distinct eras. His love for 70’s crime and heist films is evident throughout RESERVOIR DOGS, while his passion for Blaxploitation pictures from the same era fundamentally inform PULP FICTION and JACKIE BROWN. Schlocky kung-fu and bloody grindhouse flicks merged with westerns to create a distinct hybrid of styles that gave us KILL BILL (2003) and DEATH PROOF (2007). Starting with INGLORIOUS BASTERDS, however, a very curious thing is unfolding. The western genre continues to inform Tarantino’s storytelling, but rather than simply homaging that particular period, he is actively deconstructing them to discover the nature of the engine that fuels them. INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS, DJANGO UNCHAINED, and now, THE HATEFUL EIGHT come together to form a loose trilogy of Revisionist revenge westerns that directly confront America’s ugly racial history. Tarantino’s longtime, almost-casual use of racial and sexist epithets in his work has earned him several enemies in addition to a reputation as a deeply divisive and controversial voice in mainstream American cinema.

A truly equal-opportunity offender, he has never shied away from carpet-bombing his narratives with some of the most egregious profanity known to man. However, it’s hard to argue that Tarantino lacks empathy with his minority characters– they are frequently empowered to take up arms in their own defense or to right the wrongs of their persecution, and nowhere is this more evident in his last three features. INGLORIOUS BASTERDS reveled in depicting a coalition of American soldiers hunting Nazi scalps to avenge their Jewish brethren. DJANGO UNCHAINED showed a slave rising up to annihilate his white masters without losing his own humanity in the process. THE HATEFUL EIGHT evokes the profound racial tensions between Union and Confederate ideologies while simultaneously suggesting they might be more alike than they are different. Tarantino’s usage of contentious terms like the N-word in this context, while coming at great risk to his own personal character, evidences his unwillingness to shrink away from the ugly racial nature of America’s engine, pointing it out plainly for all to see. His placing of these interactions firmly in the past only highlights their importance to our modern times, and considering the fact that America’s first black president will be succeeded by an openly racist, xenophobic sentient tangerine, the conversation is far from over. Tarantino’s voice may be abrasive and offensive to a lot of people, but it’s hard to argue that his voice isn’t more relevant than ever.

Another aspect of this period in Tarantino’s career has been the huge critical and financial success of his work. After a long awards-circuit dry spell, INGLORIOUS BASTERDS marked Tarantino’s return to the Oscar shortlist– a return he cemented with the even-larger success of DJANGO UNCHAINED and its subsequent win for Best Original Screenplay. THE HATEFUL EIGHT was similarly praised, earning mostly-positive reviews that noted his continued excellence in both writing and direction. The film grossed $155 million against its $44 million budget– a notable downturn in the recent trend, but far from his worst showing.

Another aspect of this period in Tarantino’s career has been the huge critical and financial success of his work. After a long awards-circuit dry spell, INGLORIOUS BASTERDS marked Tarantino’s return to the Oscar shortlist– a return he cemented with the even-larger success of DJANGO UNCHAINED and its subsequent win for Best Original Screenplay. THE HATEFUL EIGHT was similarly praised, earning mostly-positive reviews that noted his continued excellence in both writing and direction. The film grossed $155 million against its $44 million budget– a notable downturn in the recent trend, but far from his worst showing.

Well-earned Oscar nominations for Jennifer Jason Leigh’s performance and Robert Richardson’s cinematography followed suit, calcifying THE HATEFUL EIGHT’s reputation as an excellent addition to Tarantino’s canon. As the eighth picture in what Tarantino vehemently insists will be a filmography totaling only ten films, THE HATEFUL EIGHT’s warm reception positions the controversial auteur for success going into what is expected to be his last two films. Rumors that his ninth film will be about Australian outlaws in the 1930s suggests that Tarantino plans to continue his run of revisionist westerns, but one thing we know for certain is that, whatever form the film takes, it undoubtedly will shock, surprise, and outrage.

Author Cameron Beyl is the creator of The Directors Series and an award-winning filmmaker of narrative features, shorts, and music videos. His work has screened at numerous film festivals and museums, in addition to being featured on tastemaking online media platforms like Vice Creators Project, Slate, Popular Mechanics, and Indiewire.

THE DIRECTORS SERIES is an educational collection of video and text essays by filmmaker Cameron Beyl exploring the works of contemporary and classic film directors.