Today on the show we have screenwriter and producer Erik Bork. Erik Bork is a screenwriter best known for his work on the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers, From the Earth to the Moon, for which he wrote multiple episodes, and won two Emmy and two Golden Globe Awards as part of the producing team.

Erik has also sold series pitches (and written pilots) at NBC and FOX, worked on the writing staff for two primetime dramas, and written feature screenplays on assignment for companies like Universal, HBO, TNT, and Playtone. He teaches screenwriting for UCLA Extension, National University, and The Writers Store, and offers one-on-one consulting to writers.

Why don’t most scripts have the kind of success their writers’ dream of? Because of problems with the basic idea for their story. Which the writer is usually unaware of. While story structure and scene writing choices do need to be top-notch, writers tend to rush into those parts of the writing process too quickly, without vetting their basic concept.

This is a mistake professional rarely make because their agents and managers insist that ideas be run past them first. And this usually leads to serious notes and development before the outlining process even starts.

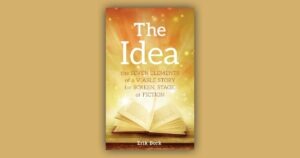

The Idea: The Seven Elements of a Viable Story for Screen, Stage or Fiction form an acronym for the word PROBLEM, since every story is really about one, at its core. Each chapter focuses on one of these seven deceptively simple-looking aspects of a strong story, which are anything but easy to master. Mr. Bork highlights his own struggles as a writer and his arrival at an understanding of how each of these elements works — and how to know if one’s idea really succeeds at each of them. A special section devoted to television writing (and its unique attributes) ends each chapter.

Whatever your education and background in writing or story, this book and its unique focus contribute foundationally useful information not covered elsewhere — which may be the missing piece that leads to greater results, both on the page and in the marketplace.

Enjoy my conversation with Erik Bork.

Alex Ferrari 0:06

I'd like to welcome the show Eric Bork. Man, thank you so much for being on the show, brother. I appreciate it.

Erik Bork 2:49

Thanks for having me. It's great to be here.

Alex Ferrari 2:52

Thank you, man. So you you've you've lived a very interesting career in Hollyweird. And your story is quite interesting from what I've been able to pick up online. So first off, how did you get into the business?

Erik Bork 3:07

Well, I moved to LA from Ohio, where I grown up and gone to film school got a bachelor's degree and motion picture production BFA right State University in Dayton, Ohio, moved out to LA started working as an assistant versus a temp worked around the fox lot for a couple of years, including a writer's assistant job on the show picket fences. Yeah, Kelly drama which won the Emmy for Best Drama that year, and the next year. And eventually I kind of had paid my dues in the temp pool at Fox, the in house temple where I'd be assigned to different sort of offices every day or every week or every month, whatever. And they assigned me to Tom Hanks, his production company. Tom had just moved on to the fox lot his deal a bit at Disney. He only had his his his like main assistant, and then me as the tamp helping get the office set up. I thought I'd be there a month at most, and then turn into a full time assistant position and eventually led to my you know, big break.

Alex Ferrari 4:03

Nice and that that must have been a fun, boss.

Erik Bork 4:08

It was amazing. Yeah, I mean, I you know, I idolized him, you know, big was one of my favorite movies. And when I started working for him the week I started temping for him was the week that Sleepless in Seattle premiered. Oh, wow. Philadelphia was already in the can and he was about to go shoot Forrest Gump. So during the during the two years that I worked as his like second assistant, he won the back to back Oscars. And it was like my job the day after the Oscars to take the statuette to the academy building and have his nameplate put on because they don't do that the night. At least they didn't then so I'm driving my beat up Toyota Celica to the academy building with Tom Hanks Oscar in the passenger seat because stuff I got to do. So it was cool being on the you know, on the in the Inner Inner sort of circle as a as an employee to him when he was at, you know, reached this incredible height. Oh, yeah, he's already Probably never, you know, never gone down from that height, because then it led to producing and all these other things which I got to be involved in.

Alex Ferrari 5:06

Yeah, I mean, that must have been a you were you were there at like a really fun part of his career. I mean, he was like, pow, pow, pow, pow, like, everything he touched was gold. And is it true that he is as nice as they say he is.

Erik Bork 5:19

Yeah, he's very nice. He's very funny. Can be cutting in his in his humor, but in a way that's entertaining. Like, he would always make me laugh. And he's extremely generous. The the opportunity he gives people is amazing, including me. And he sticks with people. And he's, he's just like a fun, easygoing guy for a big star like that, you know, you would think there'd be you know, tons of ego and insecurity and need to prove oneself or whatever kind of stuff we might think that big actors might have. He doesn't seem to have any of that. He's just like a happy go lucky guy that loves making things loves acting and, and producing and, you know, just just into it.

Alex Ferrari 6:06

That's awesome. Now, how did you get involved with Ben and brothers?

Erik Bork 6:10

Well, first there was from the Earth to the Moon, which was the miniseries that that Tom executive produced for HBO, in the late 90s. That's where my big break came in, which is that he gave me this promotion that enabled me to help him kind of ultimately write and produce that miniseries. There were steps along the way to that, but at the end of the day, I had a co producer credit, I'd been involved in every aspect of it, I had multiple writing credits on the scripts. So Banda brothers was kind of like a reteaming of a lot of the same people, plus adding Steven Spielberg as an executive producer. So so I was kind of already had done that sort of two to three year project with him before and so Band of Brothers was like, here's another one kind of, well, let's like

Alex Ferrari 6:55

so then let's go back to four from Earth to the Moon, which is one of my favorite miniseries. It was kind of like, I guess it was the beginning of miniseries. But it was kind of this kind of beginning, if I remember correctly, kind of the beginning of this, like HBO, high production value, kind of mini series. Is that Is that fair to say? Yeah,

Erik Bork 7:13

I think it was the first one. Yeah. And they spent like 70 million and it was way over the top amount of money for them to spend at that time right.

Alex Ferrari 7:21

Now. Now, that's an episode of Game of Thrones. I mean, I'm sure they weren't nervous, but that that turned out to be a huge monster hit for HBO.

Erik Bork 7:32

Well, you know, HBO it's not so much about ratings of course, it's about subscribers and how do you get subscribers if you win awards? And you have critics love it and have people think you got to have HBO in order to get this kind of programming and so we won the all the Emmys and the big awards for many series which I think was the most important thing at the end and enabled them to go okay, let's do more of these and advanta brothers was like the next one,

Alex Ferrari 7:55

and and then on from Earth to the Moon, you were a writer, and a producer just read it.

Erik Bork 8:01

My ultimate credit was co producer on all of it and writer on multiple episodes, some I didn't get credit on some I've shared credits when I have sole credit. So yeah, I was there at the beginning, you know, when it was just an idea and a book that we had the rights to that Tom had sold a pitch to HBO and I in the meantime, while working as his second assistant, I was writing all the time, and eventually turned from feature film writing to sitcom writing, believe it or not, and had written three spec episodes of sitcoms of that of that day. Three NBC shows actually, Frasier Mad About You and Friends. And eventually Tom ended up reading one or two of those because his first assistant kind of, I guess, knew I got an agent and was you know, I kind of became part of the inner circle by then and she suggested that he read one or that I give him one which I was never going to be my idea to do that had to be somebody else right? So he did and pronounced me talented and and and then a few months later said how would you like to stop being an assistant and like, have your own assistant and, you know, like this life changing thing, and helped me figure out this mini series. So that led to us. This is from the Earth to the Moon that led to us like kind of meeting for breakfasts over the course of weeks and going over ideas for each episode and me kind of helping draft this like 50 Page Bible for what the miniseries was going to be, which HBO approved, and then we use that to go get writers and, and it was also my job to help find writers like established writers to write episodes of this. And along the way of doing that, one of the other producers that I was working with suggested maybe I should write one of the episodes again, not gonna be me asking for it, but if someone else does, yes, please. So that was assigned or I chose one of the episodes that had not been signed anybody and wrote up a zillion drafts of that which were terrible for a long time because I was really in over my head and never tried to write historical drama. You know, I mean, trying to do justice To the real events and have everything be accurate, I was overly obsessed with the research and all that stuff, a lot of lessons I learned along the way. And, but eventually under the tutelage of Tony tau, who was our CO exec producer was like the day to day producer who kind of ran everything and oversaw the writers, the directors, everything hasn't like non writing producer, I found my way and my script became considered a decent one. And then I was asked to rewrite some of the other ones, which is how I have shared credit on some of the other ones. And also, I started working under Tony I became his kind of like apprentice producer like his, you know, Shadow everywhere he went. So I got to be in all the big meetings and I'll be on set in the editing room, be involved in every aspect and because I was also Tom's point person, or the first kind of like employee one in a way, not really, but close to that on the miniseries, I sort of had access and had to be dealt with to some extent. So I can be on on the set. whispering and Lily zanic or John turtle tab, or Sally Fields ear, saying, I don't know if Tom would like this really annoying, you know, inexperienced young jerk.

Alex Ferrari 11:10

I can imagine the ego might run away with you at that at that young young age, especially when given that sort of power or access. Now, then you went into BANA brothers after that. Right. Right. And now

Erik Bork 11:25

To your words, right, some other things. But then yeah,

Alex Ferrari 11:28

So Band of Brothers, which is another monster hit for HBO. That thing is a legendary miniseries on a band of brothers during World War Two. This is before Private Ryan or after Private Ryan. It was

Erik Bork 11:40

after you know, Tom, it kind of became a tradition for him. He made Apollo 13. And they decided to a miniseries about space program and he made Saving Private Ryan and he and Steven Steven Spielberg, I call them Steven, but

Alex Ferrari 11:51

to us. Yes, yes, Mr. Spielberg

Erik Bork 11:54

decided to make Band of Brothers. First they were going to do something with citizen soldiers, which is another Steven Ambrose book about World War Two. That was really just citizens who became soldiers from all over America. And then they widely decided, you know, Band of Brothers is a more one group. We're gonna stay with this one group and follow their whole story. So it's a more contained subject.

Alex Ferrari 12:14

And when working with Mr. Spielberg, how did you did you work with him? How was that process? And I imagine that that must have been overwhelming just meeting him or if you if you did meet with him and work with him on this it must have been it Steven Spielberg, you know, I mean it but you're the more you work with Tom Hanks, which is great. But now you're just like, this is a whole nother level of in different vit flavor of crazy.

Erik Bork 12:42

Yeah, and I don't think I ever fully got over the That's Tom Hanks right there. And we're in the same meeting. Like there's a certain like, thing that never fully goes away. So yeah, so Steven was, was like, there with Tom to kind of oversee, like, all the big decisions he was he didn't direct any episodes, he wasn't like on set every day or anything like that. He would strategically come and visit or be involved in certain meetings, you know, looking at all the cuts and giving notes on the cuts. So I was, you know, I had quite a few experiences where I was like a group of us in a meeting, including Steven. And, you know, he was just like this infectious kid with this love for filmmaking who couldn't wait to tell you how they got that shot inside Saving Private Ryan from like, the steeple or whatever, you know, like, here's what we did, you know, like it was he's just like, kind of similar Tom in a way kind of boyish. Just infectious enthusiasm. And love for love for the craft. But yeah, it's, it's, it's certainly certainly a little overwhelming to be, you know, to be in his presence as well.

Alex Ferrari 13:47

And you and you were many of those meetings, I'm assuming?

Erik Bork 13:50

Yeah. Yeah, there were quite a few. And I got to ride on a private jet once where it was just me and Tom and Steven, from London to LA, because we shot it all in in England. And, and that was pretty cool. Just the three of us the three bros.

Alex Ferrari 14:06

Just chillin, just hanging out. You know, talking about stuff. I would love to have been a fly in the wall on that. Now, so can you give a one tip that you would get what is the one tip that you would give a writer that wants to break into TV? And once it can't try to get a TV kick?

Erik Bork 14:25

Wow, that's a quite a big segue. The one tip well, you know, keep at it. I mean, it's a persistence thing that was a tip somebody gave me when I was first starting out some established greenware just like don't give up and keep doing it and keep learning as you go getting feedback, learning and growing and understanding it's a marathon. And it's, you know, it's rare to achieve something and to write something that would allow you to break in and, and there's usually a long learning curve So you got to see it as an education and ongoing. I mean, I still feel like every script I'm writing, I'm learning and I'm, I'm like a small child grappling in the dark with something that's beyond me. You know, it's always that way and have this sort of open mind of I'm learning and I'm and I'm, and I recognize that I am a kind of a neophyte, maybe always, every new project, I'm a neophyte again, and embrace that and just be about I'm going to learn and grow and improve.

Alex Ferrari 15:29

Now, let's, now let's talk about your book, the idea the seven elements of a viable story screens for screen stage and or fiction. That's a mouthful. Can you talk about the idea? And what made you write the book?

Erik Bork 15:43

Yeah. So I've been teaching screenwriting coaching and mentoring writers for the last 10 years, as well as writing my own stuff and doing my own projects. And, and what that's taught me is something I kind of already knew, but became even more clear, which is that it all lives or dies with the basic idea that so much of what makes a project viable is contained within the basic premise, you could pitch somebody in a paragraph or you know, 30 seconds or whatever. And that most of the time, we writers want to jump into the actual writing of the script, without really vetting the idea without spending enough time trying to arrive at an idea worth writing. And so when I give notes to a writer who sends me their scripts, like 90%, plus of the most important notes I have on their script, the modes that most determine whether it's going to succeed or not, are notes that would have had on that 32nd Pit, if only the idea before they wrote any of the scenes or even outlined it, or even did a sort of structure, you know, document. So and also, in my own career, like, there was a period where I was pitching ideas for series to the network's like drama series, and my agents would send me out to all these producers and studios and networks and, and, and I would have to get, you know, get an idea for a series pass them. First, I'd get past my agents, which was the hardest part almost, because they were very tough on, you know, we're not gonna send you out with some idea that we don't really believe in it. So I kind of had to learn for my own sort of making a living at that, what makes it viable ideas become this, like ongoing obsession. And so I kind of figured out based on as a writer, as, as a producer, and as a coach and teacher, what makes an idea worth writing, what are really the elements. So and I've been blogging about the craft for close to a decade now. And so some of this originated my blog was like, Well, I really figured I really kind of worked it out that there's this acronym of seven elements using the word problem as the acronym because every story is really about a problem that takes the whole story to solve, essentially. So the problem needs to have these seven characteristics. And each one gets a chapter where I go into great depth on the pitfalls and how to make that element really come out in your work, whether it's film TV, or you know, I think it applies to fiction and other kinds of stories as well.

Alex Ferrari 18:08

So what are this? Do you mind telling us the seven key elements?

Erik Bork 18:11

Yeah, so it's punishing, punishing the problem, says a punishing problem. Right, so PRL BLM, so punishing, relatable, and these things describe not just the story, but the problem at the heart of the story, because that's really what you're pitching. When you're pitching a story, you're pitching a problem that takes the whole story to solve. So what does that problem have to look like? It has to be punishing to the main character, which means just defies being solved. And even though they're actively trying to solve it throughout the story, mostly, they're failing, and they're losing. And it's just getting more complicated and difficult and important all the way through. I liken it to watching your favorite sports team and a championship game where they're the underdog, and they're behind. It's exciting to watch that. And hopefully, they'll come from behind at the end and win the game at the final moment. But prior to that, there's a lot of things going wrong and you're on the edge of your seat. So punishing. The second one is relatable, which has to do with caring about the main character or characters and whatever the outcome of the story is. That's that's in play. You want the audience to invest emotionally in that it's not as easy to earn that investment as it might seem investment and both the main character which most movies have a single main character. Most TV episodes have multiple characters that get stories, investing in them, and also investing in whatever it is they're trying to achieve or solve. The third is original. Before fourth is believable. I should say just original. It's like fresh twist on a familiar genre due to the way to go in my view, as opposed to I've got to do something totally different from how anyone's ever done anything before, which usually means you're not observing these other six elements, because you're all focused on being different. So it's really about building on the shoulders of things that have worked but with some intriguing fresh element your brain to it. believable, that's obvious, but so many scripts and even premise For scripts fail, when the audience is just like, I don't know that I buy this, right? I don't believe these people would do this or this situation, it's very complicated and arbitrary that you've set up and I'm not sure I'm with you. So believability is a bigger one than it seems that L is for life altering, which means the stakes of what's going on have to really matter. He is entertaining, which means don't forget your job, really bring your audience to some emotional state they've paid to be in because they want this kind of genre to do something for them, whether it's Action, Comedy, Romance, whatever. What is the entertainment? How do you achieve entertainment? How do you make sure that's part of what you're doing. And then the last one is meaningful, which has to do with theme, and making sure that what you're writing has some resonance beyond the surface events of your story. So people feel like, you know, you've kind of it sticks to their ribs in terms of what it's really about, and and the human condition and life issues and challenges that we can all identify with.

Alex Ferrari 21:03

So it says you've been teaching so long, and mentoring and you've obviously read a bunch of scripts over your course of your career. What is the biggest mistake you see first time screenwriters make?

Erik Bork 21:18

Well, when you're first time screenwriter, you know you're learning the craft. So there's a lot of things that you don't know how to do well yet. But if we just talk on the concept level, I mean, the biggest mistake really is the one I already said, which is trying to jump too quickly into writing without getting the concept. But if we put that one aside, one of the really most common ones is issues with point of view, and that's covered in the relatable chapter, which means not understanding that you have to tell the story subjectively, from the point of view of a character that the audience is meant to kind of become one with almost like it's happening to them. And that's not easy to achieve. And there are specific practices and things to avoid in the achievement of that. And writers tend to either not realize that or not do that effectively. And so the first goal I think, is you know, you want to suck the reader into caring. And you usually do it through a specific individual character by by not telling it objectively but telling it subjectively and it's not just first time screenwriters though, I mean, we all struggle with that making the audience care and, and, and making them feel like they're inside the story is, you know, always important and often difficult.

Alex Ferrari 22:27

Now, can you name a given example of a protagonist, an interesting protagonist, and why we connect with those that protagonist anywhere in cinema?

Erik Bork 22:39

Well, for some reason, Forrest Gump just you know, Michael Hague, in his book, writing screenplays itself is a great section on empathy and the different techniques for gaining empathy. And a lot of it when you really look at it is a manipulation on the part of the writer, a very conscious manipulation of giving a character certain elements that make you care about them save the cat talked about, they have to save a cat in the first pages, which is kind of a joke, but it's actually true. They have to do something that makes us sympathize, and feel like that's a good person. I like that person. You know, there's this real vote, invoke thing of unlikable main characters and anti heroes and people point to shows like Breaking Bad and say, Look what a dark figure he was. And I always say look at the pilot of Breaking Bad, and he was the most lovable, relatable average every man you could ever possibly meet, who had all of these undeserved misfortunes, which is a phrase Michael Haig uses when you give a character undeserved misfortune, like Forrest Gump didn't ask to be mentally handicapped and have those things on his legs and have people make fun of them. It's not fair. You immediately side with the poor, lovable nice kid who's got these unfair things about his life. He didn't ask to not have a father. You know, he didn't ask to be picked on and chased all these things that are just totally not fair. And in his simplicity, there's a goodness and a love ability that just makes you feel like he's your kid. Like you just want to protect them. So you know, the the Africa is gonna say about the undeserved misfortune, but another thing is when you put a character in jeopardy, so that so that we're worried about the character, which they do that with Forrest Gump, as well. And Michael has this whole list of things that are really genius that he's observed in movies over the years, but so much of the time you'll be reading a script and it's like, yeah, I don't have a strong pull to this person.

Alex Ferrari 24:35

I don't care.

Erik Bork 24:36

Oh, I was gonna say Breaking Bad there all these elements of undeserved misfortune. It's like he's a chemistry teacher who's passionate and good and his students couldn't care less. He doesn't make enough money siesta moonlight at a car wash where his students see him and make fun of them. Yep, he finds out he's dying. He doesn't have enough money to leave his family after his death. This poor schmuck, right so You need to do all that for the audience to then accept when you start cooking math that okay, this is only option and we get why he's doing it and we still love him and he's still in way over his head once he starts cooking math way over his head, you know, there's dangerous people everywhere and he's gonna get arrested and it's like are killed yeah are killed. It takes a very long time for him to become the kind of like, you know, heavy the kind of like, top of his Eisenberg scary guy of Heisenberg. Yeah. So I just think it's a mistake to just say, Oh, you can make your character really unlikable. And it's fine. I don't even worry about it. It's not you can't get away with that as easily as it might seem. So I've always explained to people well, here, this character that you think is unlikable. In this thing that really work. Let's look at all the things that actually make them likable. And usually, there's quite a few of them that people didn't even notice.

Alex Ferrari 25:51

So if you look at someone like Wolverine, or Logan, you know, who is an anti hero, quote, unquote, there's things in his backstory that, you know, it's unfortunate he didn't want he didn't end up he didn't want to become over and it was forced upon him. He lives in a constant cycle of always healing, not really aging, so he could live for hundreds of years and see people die. Like there's a lot of things that from luck, if you go back to like even the Vampire Lestat, you know, who's a very unlikable, he's a villain, he's a villain, but you kind of go with him a little bit. And you see his from his point of view what he has to go with. So even the most unlikable characters in history, and literature, they all have this kind of thing you're talking about, like Breaking Bad, I still say is one of the best series ever written, ever shot and ever created it. It's just it's perfection in my edit, from the beginning, from the best pilot I've ever seen to the one of the best endings I've ever seen. And how they took that one beautiful, lovable guy and turned him into Heisenberg, who was you know, was spoiler alert, a murder? Ego maniacal maniac he turned him into essentially, but there was always those little clips of, of the of the teacher of the chemistry teacher always sparkle in his eye every once in a while. Would you agree?

Erik Bork 27:11

Yeah, for sure. And I would say the other key with like, if somebody is unlikable, if you really pile the problems on top of them, big problems that makes a big difference, because the audience can't help but relate to the character with the big problems like Scarface, pretty unlikable character, but he's got he's facing death around every corner, essentially, right? And if the character gets really beaten up by the events of the story that helps you forgive unlikable qualities, but don't forget Life and Death type stuff.

Alex Ferrari 27:38

Right? And also, don't forget where you came from, though. He was you know, right. Refugee, your dog.

Erik Bork 27:43

Yeah, completely thought his body killed with a chainsaw in front of them, you know? And that one scene? I mean, it's like,

Alex Ferrari 27:50

yeah, it's insane. Now, on the other side of that, what is an amazing antagonist? And why do people like Because? Because a lot of people, right? I've read so many scripts, horrible villains, and in movies, horrible antagonists. And I always use my favorite antagonist, one of my favorite cinematic antagonists of all time is the Joker and Dark Knight, who's just as perfect of an antagonist, because he mirrored Batman in every way. He was the opposite. You know, and I love that what is your What, in your opinion, what makes a great antagonist and if you have an example of that,

Erik Bork 28:27

well, the three dimensionality, you know that they're the human being that we can understand why they are the way they are, and they're not. People. They're not the same as every bad guy we've ever seen. They're not a one dimensional mustache twirling villain read my mind. Yeah, but they're also not just the standard version of their villain who talks in a nice and cultured way like they're your friend, but they're really, you know, not one that comes to mind is you know, Christoph Waltz and Inglorious Basterds, right? I mean, he that opening sequence, oh, he's just, I mean, he is kind of he is on one level, he is that version of pure evil, pretending to be super friendly, and have a sense of humor and be cultured, and I'm working with you. And we're friends, which we've seen a million times, but this but this that's where the Oh, and the originality comes in the specific way he's written. And the way he performs it somehow transcends even that kind of that cliche

Alex Ferrari 29:26

terrifying. It was terrifying that that seven minutes scene is one of the Oscar I believe that's first seven minutes, just like well, that's just give it to him. Yeah. There's no There's no, look, no question. And someone like Hannibal Lecter, who is an amazing anti hero, like you are literally rooting for a serial killer who eats people?

Erik Bork 29:47

Well, and I would point out, he's not the antagonist in that movie, right? He's the helper of the protagonist. Right? And he's, yeah, he's super interesting. You understand what he wants and what gets in the way of that. So it kind of has his own story but both a Buffalo Bill shaped by Ted Levine, who was the star of the first thing I ever wrote professionally, which was an episode of from the Earth to the Moon. He played Alan Shepard. He's such

Alex Ferrari 30:11

a he's an amazing actor. He, to me

Erik Bork 30:15

Buffalo Bill is what makes that movies people never talk about him. But those few scenes of him being creepy alone are so real and feel so just like not like other serial killer things in movies where the because even Hannibal Lecter is kind of glamorized look at what a genius he is, or whatever she was find. I mean, Anthony Hopkins obviously transcended this, but I always find that I don't love it. When serial killers are portrayed as these like incredible geniuses, they're outsmarting everybody. Somehow Buffalo Bill. Yeah, he's outsmarting on one level, he knows how to like kidnap women and keep them hidden and all that stuff and not be found. But he's just this twisted, sick two days just to see that felt very real.

Alex Ferrari 31:01

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Erik Bork 31:12

And as a major threat feel very real. So whenever you cut to him, to me that you don't get to know him that well, but talk about an antagonist that just powers the whole movie, you just want to see that girl saved and, and you really believe in the reality of Buffalo Bill,

Alex Ferrari 31:28

she puts the lotion on the skin. Yeah, she gets the hose again. I mean, that was a brutal. I mean, it's such a brutal performance, wonderful performance. But then later on, as the series continued, then the hero is Hannibal Lecter, and Hannibal and oh, right, Red Dragon and these kind of films, which is kind of like what, like you're rooting for syrup, like you're rooting for Scarface, or you're rooting for Heisenberg. And you're like, does that say something about me as a viewer? Or does it say something about the writer who wrote that's

Erik Bork 32:03

the manipulation that the writer is doing to make you see things through the perspective of somebody that you otherwise would recoil from? And to give them problems that you want to see them solve, despite not liking certain things about what who they are?

Alex Ferrari 32:19

What is your feeling on the Joker? Like, if we could just dive in a little bit on that character? Because I know, I don't know what your feeling of that movie is. Or if him but I've always found them very interesting. And I think he's a great case study of what an antagonist should do for the protagonist.

Erik Bork 32:37

Yeah, I mean, Heath Ledger was amazing. I'm not a huge dark night person myself, which might be sacrilege to you and all

Alex Ferrari 32:45

viewers, it was a great interview. It's a fantastic interview, it's actually

Erik Bork 32:48

not my genre, I'm actually more of a like, romantic comedy type of guy to believe it or not, I mean, people see Band of Brothers, and they think, oh, high testosterone, guys with guns. He also writes about astronauts. So I was very much you know, after those two people were always trying to put me on cop shows and stuff like that, which was the antithesis of who I am as a writer what I aspire to be so. So a lot of my favorite stuff doesn't have a villain doesn't have that antagonist, because not every genre or every kind of movie has to have sure that's straight up evil person with life and death stakes. Most of my favorite movies don't have life and death stakes. They have important life stakes, but it's not someone's gonna kill me kind of stakes. Right? So I'm probably not the best person to analyze the Joker or the Dark Knight too deeply. So I'm trying to say it

Alex Ferrari 33:35

Fair enough. Fair enough. So okay, so then that's, that's a good segue, though. So then, let's pick one of your favorite romantic comedies, and see what is the the conflict? And how do we get to those? Those Eric, can we break that down? A little bit? Sure.

Erik Bork 33:51

Well, 40 Year Old Virgin is a great one. Yeah, it is. That, you know, I think people think is great writing and was, you know, successful on every level. So we could talk about that if you wanted. Yeah, sure. Absolutely. Yeah. Yeah, so um, doesn't have a villain, you know, just has a guy who you fall in love with, because he's got this really big problem.

Alex Ferrari 34:13

He's a 40 year old virgin.

Erik Bork 34:15

Well, the problem and now everybody knows, right, like the catalyst of that movie is that they find out the poker game that he's a virgin. And now, he already had a problem. But now he has a pressing crisis problem, which I think all the great main characters have that, you know, in the beginning of that movie, he hasn't necessarily experienced life as problematic prior to that moment, right. He's just going along living his compromised life without necessarily seeing it as compromised. You know, save the cat talks about the main character should have six things that need fixing that we need that we learn about the setup or the first 10 pages. So he's got all these things like you're sort of like looking at his life. going, Wow, this is like, huh, but he doesn't know it, right? No, he's happy. He's happy. Dealing with crisis happens. And then the whole rest of the movie is going to push him and force him and pressure him in the most uncomfortable under siege kind of way to fix those things that needed fixing that he didn't acknowledge. Which means overcome your virginity and figure out love and relationships and and move forward as an adult man who doesn't have life size Yoda is sitting behind him. And that's

Alex Ferrari 35:27

for everyone listening. I do have a life sized Yoda have small Yodas

Erik Bork 35:31

other action figures, they

Alex Ferrari 35:32

seem to be a Wolverine and some hawks in the background. I'm fine. I'm very, I'm very comfortable in my adulthood. And in my own manhood, sir. Thank you. I appreciate that. You know what, 3040 years ago, this would have been an issue but now I'm just one of the guys.

Erik Bork 35:50

Well, you see a Bill Maher's new rule thing about Stanley No, as you know, he got his big trouble because recently Yeah, so he taught us so he talked about on his show last week in his like, new rule that he does at the end. And he really went after it about how people are, you know, people that are obsessed with like, you know, fanboy culture need to grow up and all that kind of stuff. In his view. He was like, he's like, he said, I'm not I'm not happy, Stanley's dead. I'm upset that you're alive. Everybody who reveres comic books as as like high art and culture, whatever. That's his point of view. I'm not saying I agree with it. It was funny. It's

Alex Ferrari 36:30

Yoda up, I'm gonna have to defend Yoda for a second. I bought Yoda in 1999. The conversation would not be as clean today with my wife. I said, Hey, babe, I need to buy a $500 life size Yoda. Oh, I know the girls. I know my kids need, you know, summer school, or you know, or summer camp or after schools. But conversations that have been had today. Same thing goes for all the statues? Or different times of their artifacts of my earlier life. I can't get rid of just yet.

Erik Bork 37:04

To do that while you could because never again.

Alex Ferrari 37:07

No, no. Just note for everyone listening. If you're going to buy a life size Yoda or a giant I have a giant alien egg to if you're going to do things like that. Do it when you're single. Or do it before the kids come? Yeah, that the conversation changes. Yeah. Anyway, back to what you were talking about as to Virgin, but he finally did finally leave he did become a man and had sex and, you know, had a relationship and sold his toys and built up a you know, he said he just changed his life. But that's very interesting that so many writers and understand that is the that the protagonist should not know that he or she needs to change. And they are there.

Erik Bork 37:50

Yeah. Yeah. Michael Haig is great on this too. I sound like I'm promoting Michael,

Alex Ferrari 37:53

who's my friend Michael. I'm great friends with Michael too. And he's Michael actually wrote

Erik Bork 37:57

a blurb on the back of my book that said something like don't read any other screenwriting book, including mine, until you've read Eric Bork the idea so this guy is a match,

Alex Ferrari 38:06

you need to you need you owe him at least a royalty or two.

Erik Bork 38:09

And We team teach a class once in a while for this screenwriting program in Sweden that we're both kind of adjunct professors where we do it all in line from here. But anyway, he talks about his one of his big specialties is the whole character arc stuff. And he talks about how the main character most of the time in most movies is living in what he calls their his identity instead of his essence. And his identity is this compromised version of himself that is the result of like childhood experiences, and pain and issues that that caused the character to become something that's a sort of limited, protected version of themselves that they project to the world, not their full, best self and they don't believe that full best self as possible. They don't even try to access it. They just are comfortable, somewhat in that identity. He uses like the example of LA Confidential, Russell Crowe's character who saw his like, Mother beaten to death by his father while I was tied to radiate or something like that. He says in this like bedroom scene with Kim Basinger. And, you know, he always thought of himself as dumb, and just as muscle and that's how he's been treated. He's just a muscle guy. But he wants to be something more than that. And in the movie, thanks to the relationship with her, he starts to see the possibility of that because she believes in the essence, which is what a great love interest should do. They should see the essence. This is like just quoting Michael Haig, right and you might want him sitting here.

Alex Ferrari 39:33

He's been on the show too many times. I can't keep bringing them back.

Erik Bork 39:36

So they see beyond the he's probably said this already then he they see beyond the identity and they see the essence and they help you become the person that you want to be or you know, the as Jerry Maguire that line I love the man he wants to be in the man he almost is

Alex Ferrari 39:51

Oh, great. Oh, yeah. No, that's an amazing romantic comedy, but it's not. It's kind of a romantic comedy, but it has its own

Erik Bork 40:00

Well, lever. It's got two stories and one and one is the story of Jerry and his sports agent in problem his career. And the second is the love story. Right? So, I mean, those are my favorite kind of movies usually aren't just about, well, these two people be together, but there's something else one or both of them is trying to do that isn't going to affect their future life. And that's really important and entertaining to watch as well. So yeah, that's a great example of that. And the love story is kind of told more from her point of view, which is interesting, usually the main character, you know that they have an a story problem, which is I lost my career and I'm trying to get it back, then they have a BS story. Often it's a relationship conflict or challenge, which is I've met this person, but there's a problem and is it going to work out or not. And while he has some scenes, about his point of view of the relationship, there's more scenes of her point of view on the relationship and you see that she has more to lose and more to gain. She's the one who we're seeing really is in love with him and wants him whereas he's more like on the fence can't really commit while his careers in upheaval, like men often are. And so I just think that's an interesting lesson when you start looking at a story and B story and point of view that it flips how it's usually done, where it gives the B story love interest, kind of like a story from their point of view. So we're really telling two stories in one which is often the case in romantic movies where you're kind of following both people in the couple and their life problems and point of view and what this relationship means to them as opposed to movies that aren't about a romantic relationship primarily are usually we fall in one person and they might have a love interest as the B story but we're always just with them. You know, Chris Pratt and Guardians of the Galaxy he has this like minor B story love interest with you know, Zoe cell, Donna. But it's all from his point of view. It's never from her point of view,

Alex Ferrari 41:52

right? You never hear her how she feels about any of that. And on a Jerry Maguire note, did you know about Jerry Maguire? Did you ever visit the Jerry Maguire video store?

Erik Bork 42:05

In LA? What is that? No,

Alex Ferrari 42:07

there was a there was an installation done. This is these guys are insane. They're VHS heads like they just all they do is collect old VHS. And they collected they have the world record for collecting every Jerry Maguire VHS they could get their hands on and they built a video store out of Jerry Maguire VHS is and the only thing you could rent or buy is Jerry Maguire VHS. And then after the installation, they're like, Well, what are we going to do with all these Jerry Maguire? VHS? They're building a pyramid in the desert somewhere out of I'm not joking. I've seen this if they're trying to get like, the right like it's all being crowdfunded. So they're like getting the money and they're like having an actual architect how they're going to do it, how they're going to seal it. And they're going to build like this pyramid where you could walk into the, to the temple require all made out of Jerry Maguire. VHS is it's

Erik Bork 43:05

baffling. Now is this an irony thing? Are they true fans?

Alex Ferrari 43:09

No. I think it's an I think it's I think it's a well they're obviously they're fans that movie. I mean, who isn't if if you don't like Jerry Maguire you're dead inside. But I mean seriously. I agree. There's like Shawshank Redemption, you know, like Shawshank Redemption, you're dead inside. I'm sorry. I can't talk to you. But do you electronic redemption? Yeah. Okay, good. We could continue this conversation. No, but I think it's a little bit of both to try to do like an artistic irony to like, a commit message or statement. But they are like they've said very much we love Jerry Maguire. Not it's not like we live Jerry Maguire but we just thought wouldn't it be amazing to have a video store that was just built out of Jerry Maguire? VHS is our

Erik Bork 43:51

I got to look that up. I think I have it Jerry Maguire VHS. I also have

Alex Ferrari 43:55

people who send them. People when they put the word out and people would send them from everywhere around the world, they would just send boxes of German because there's only so many thrift shops in LA that you can get them from so he got them they come from internationally. It's it's an insane process project. But anyway, I just thought that would be a nice antidote.

Erik Bork 44:16

Yeah, I'm gonna look that up when we're done here. You see you learn something pictures, you learn something

Alex Ferrari 44:21

new every day. Now, what is one thing? And I know you probably get this question a lot. And since you are a screenwriter in Hollywood and and have had, you know success as a screenwriter, what does screenwriters do to stand out of the crowd? Because there's so much more competition even when you were doing from Earth to the Moon. It's a massive different business than it was then.

Erik Bork 44:46

Well, I mean, I'll say something that buyers will often say like producers, when you're pitching something or like executives at Studio or network or whatever, which is that they love it when a writer comes in with something that only They could have written, right? That's really their voice their personal obsession in some way. Now, not every script can be 100%, your personal obsession, how many personal questions do we all have, but your particular point of view on the world and on the story, and the characters that is different from how anyone else would have done it? I mean, it takes time to cultivate a voice. And that's really like at a mastery level when you have that kind of voice that people go wow, that's, you know, that's, that's Joey Lachman. That's Charlie Kaufman or, you know, Tarantino, parents, you know, Woody Allen, you know, I mean, sort of, yeah. Sorkin for sure. Yeah. It's so it's like cultivating who you uniquely are. So that what you're doing isn't trying to stand out. It's just being organically you as a unique individual that's unlike anyone else than any other writer. And you're applying that to whatever you're writing

Alex Ferrari 45:55

there. And that is a that is a rarity. If you start thinking about how many writers can we name off the top of our head that their writing style is so distinctive, just by like, you read a few lines, you're like, Oh, that's a Toronto script. Or that's a Sorkin script, or that's Shane Black script, or that's a cop Kaufman script, or Woody Allen script. Like, they're just so specific.

Erik Bork 46:17

I don't know that it needs to be so distinctive that anyone could tell right away. But it's just like, I mean, Vince Gilligan same. Yeah, you got a very particular voice he had on The X Files he had, he had on Breaking Bad. And, and so it doesn't have to be so crazy specific that you're like no other writer on Earth, it just has to be you, fully you. And if you're fully you, you're going to be unique. And if you fully can somehow follow what interests you, and what you think is good. I believe that's the path just standing out. Rather than trying to sort of like game the system and make yourself standing. Certainly, there's marketing tricks and people like, you know, get scripts to people in weird ways or whatever. But in terms of the work actually holding up and staying on its own. That's what I would say,

Alex Ferrari 47:03

Yeah, I always tell people that if you if you are yourself, there is no competition. Yeah, because you can't compete against you just can't, it's just this. I'll never be Kaufmann. I'll never write like Sorkin that that's that. And as much as you try to be them, you're never going to outsource and spark never

Erik Bork 47:24

to have them anyway. Exactly. One view.

Alex Ferrari 47:27

Exactly. No, real quick, what any advice on pitching? Because you've been in a couple pitches, I'm assuming in life?

Erik Bork 47:34

Quite a few. Yeah.

Alex Ferrari 47:36

Any advice?

Erik Bork 47:37

Um, well, one of the things that are that you're always told when you're pitching this similar, what I just said is that you want to start with why you why this? What is your personal experience, and the more you have an anecdote, that's its own story from your own life that is engaging to people and gets them starting to be on your side, almost like you want them on your main character side, as the writer who came to this and want to do this for certain reasons, that's a great way to begin. And that's part of how you establish that only you could have written this the the way you're writing this and you have reasons for doing so that come from somewhere really genuine within you. So that's one thing. That's certainly one thing. But another thing I would say is like, what's really hard for writers often is to learn to look at their story and their basic idea for their story from kind of 30,000 feet zoomed way out just the concept level or like the logline level when you're pitching, unless you're really in a formal pitch setting where someone's going to sit there in an office and let you have 15 minutes. Any other situation, you're going to bore people to death and irritate them. If you try to explain your whole movie and go into great detail about everything that happens. And writers often make that mistake. Nobody wants to hear that. At most. They might want just the basic concept like a logline. And then if from the logline, they go, Oh, well, that's interesting, tell me more about whatever, then you're free to go further. But writers tend to bore and alienate people a lot. On the business side, it's like you're at a panel and you're talking to some producer manager. If you go up and say, Hi, I have this script, and it's about this and this happens. And this happens. There's evidence of that. And then this happened. And the reason they do this is because the person is just like someone shoot me in the head while they're listening to that they you know, it's uninvited sort of like pitch rape, you know, like

Alex Ferrari 49:26

I'm so gonna steal that my friend. I apologize. I'm telling you right now. Ah,

Erik Bork 49:31

I don't think it's very appropriate thing to say, but it is sort of like that. You're just Why are you hitting pitch violation, pitch violation and act interested in this thing that I have you you know, but I understand because writers are desperate and they want to like they just think if they talk about their story to the right person, they hear all the cool details, that person's gonna love it, but it doesn't really tend to work that way.

Alex Ferrari 49:53

Now, I'm gonna ask you a few questions. Ask all my guests. What advice would you give a screenwriter wanting to break into the business today?

Erik Bork 50:03

Good things that I haven't said already. You can review. We talked about TV a little bit, we talked about film I guess you know, don't expect a white knight who's going to make it all happen for you. And this probably fits your ethos,

Alex Ferrari 50:26

Calvary, the Calvary is not coming.

Erik Bork 50:30

Yeah. And just be be about, you know, be about. It's kind of counterintuitive in a way. But it's like writers who focus all on the marketing and the trying to get their stuff to the right people. It's, it's a frustrating truth that you're probably not going to ever find them, but they will find you when the work is ready. But when the work is ready, you're not desperate for them anymore. Because somehow, you've just gotten to a place where the whole gestalt of you and your writing has elevated to a level that it's the next logical step. Like everything that happened in my career was the next logical step from where I was just prior to that it wasn't like some, even though like Tom Hanks gave me that big promotion, which was a huge thing. But a lot of things happen on the way to that. And a lot of that was in my own kind of consciousness and my own building up of self belief, which came from doing a lot of work, getting a lot of feedback, doing all the things that you do as a writer, to you know, learn and grow and get your stuff out there. But mostly failing, you know, so understand that it's a failure process. Like you're mostly going to have rejection and failure and people that have no interest in you. And try not to get bitter, and blame those people, and have more of an attitude of I'm just going to be always learning and growing. And it's about the work. And what it's really about is the audience. The work I'm doing is supposed to delight an audience. So how do I serve them? As opposed to how do I get served by an industry that seems to not care about me? The more you focus on what you're giving, the more you're going to create stuff that actually people will then want like any business

Alex Ferrari 52:08

That's amazing and also in life the more you give the more you receive. Yeah, very very cool. Can you tell me what book had the biggest impact on your life or career

Erik Bork 52:22

probably The Catcher in the Rye

Alex Ferrari 52:23

it's been on the show many times what is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film business or in life? Oh,

Erik Bork 52:33

good one well, probably the one that I just said because I feel like I'm still having tried to learn every day the whole idea of Don't Be about what you can get be about what you can give and be kind of sort of selfless in that way. It's like a daily challenge

Alex Ferrari 52:47

fair and especially in this business.

Erik Bork 52:51

And the War of Art is a great book all the way up before to hear about you know how to get the right mindset about you know, what you're doing and how to fight through resistance then the part of you that doesn't want to do the work and doesn't believe in it. I did

Alex Ferrari 53:05

an entire episode on The War of Art because it was such an amazing it's really an amazing book and Steven I couldn't get Stephen on the show but he sent me I think boxes of books to give away to my audience like insane amounts of books that he gave all of his books all of his books and he's that that one and then do the work which is another great one the sequel I think to war of art

Erik Bork 53:27

which was a turning pro turning pro and then do the work and then do the work okay, I haven't read do the work but I read turning

Alex Ferrari 53:33

pro Yeah, turning pro isn't a great one. And then the toughest question of all three of your favorite films of all

Erik Bork 53:38

time. The World According to Garp great movie um I think the one that I haven't said already well, the godfather and Austin Powers International Man of Mystery. It's great movie the top 20 For sure.

Alex Ferrari 54:00

It's awesome and and to go back to finish it off the book and the interview with with Tom again. I remember watching Tom Tom Hanks, talk about godfather and how all problems in life can be solved by watching the Godfather all the answers to life are in The Godfather. If you have a deep problem watch The Godfather The answer will appear.

Erik Bork 54:27

I don't know if I ever heard him say that. That's funny though. I thought he would say

Alex Ferrari 54:31

I saw it in the like one of the behind the scenes documentaries on the Godfather like the 13th and 14th anniversary, whatever it was. And then where can people find you and your book? The idea?

Erik Bork 54:41

Yeah, so the book is on Amazon. I have a website that has info about the book and all my coaching and consulting and a million blog posts that are that are helpful for writers. It's called Flying wrestler and why. So flying rescue dragon ball back to World According to Garp when I was looking for sort of like I don't know why I just wanted like so a catchy name for my blog that rather than just Eric Bork blog, or some kind of like screenwriting advice.com, or whatever. And that movie was a real inspiration to me as a teenager I saw in the theater and it kind of changed my trajectory in life in a way as far as wanting to be a writer and even a screenwriter. And it's about a wrestler who's, who's obsessed with flying. But I also thought that that was a kind of metaphor for writing, that you're, there's a transcendent quality that there can be where you're like flying, but there's also a wrestling with the material like a day to day sort of struggle and wrestle. So I like this sort of opposite peneus of that, and how they're both contained in one thing.

Alex Ferrari 55:44

It's a very, it's very deep, sir. It's very deep. Thank you. Eric, thank you so much for taking the time out to talk to the tribe today. I truly appreciate it, man. Thanks again.

Erik Bork 55:54

Thank you for having me. Totally. My pleasure.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

LINKS

- The Idea: The Seven Elements of a Viable Story for Screen, Stage or Fiction

- Erik Bork – Official Site

- Band of Brothers

- From the Earth to the Moon

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Filmmaking or Screenwriting Audiobook