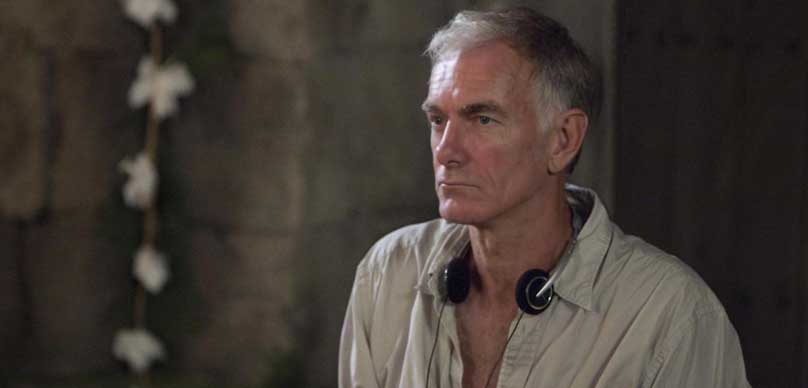

Today on the show we have legendary independent filmmaker and Oscar® nominated screenwriter John Sayles.

John Sayles is one of America’s best known independent filmmakers, receiving critical acclaim for films including Eight Men Out (1988), Lone Star (1996) and Men with Guns (1997). He’s also written screenplays for mainstream films such as Passion Fish (1992), Limbo (1999), The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008) and did a draft of Jurassic Park (1993) for Steven Spielberg.

John has been named by American critic Roger Ebert as

“one of the few genuinely independent American filmmakers”,

which John modestly denies!

John has directed over 20 films and written well over 100 screenplays throughout his career. Two of his early films, The Return of the Seacaucus Seven (1978) and Baby Its You (1982), were selected by the United States National Film Registry for preservation in 2012. John was born outside Scranton, Pennsylvania and graduated from Williams College.

John is a talented screenwriter as well as director; he made his first professional short film TSR: Thirty Seconds Over Reims (1971) after winning a talent competition with a script for the film. John’s work often touches on social issues – including unemployment, inner-city violence and war – which John believes make excellent material for stories due to complex personal relationships involved with these topics.

John also discusses his career path, including his decision to become a screenwriter, the difficulties he faced working as a screenwriter in Hollywood and his experience of writing for other directors such as Steven Spielberg.

John and I had an amazing conversation that was full of knowledge bombs. It was truly like being in a filmmaking and screenwriting masterclass, hence the title of the episode.

Sit back, relax and get ready to take some notes. Enjoy my epic conversation with John Sayles.

Right-click here to download the MP3

Alex Ferrari 0:00

This episode is brought to you by Indie Film Hustle TV, The world's first streaming service dedicated to filmmakers, screenwriters, and content creators. Learn more at indiefilmhustle.tv. I like to welcome to the show, John Sayles. How're you doing, John?

John Sayles 0:15

Good.

Alex Ferrari 0:16

Thank you so much for coming on the show my friend, I truly truly appreciate it. I've, like I told you off air it I'm a huge fan of of your work over the years. And, and you when I was coming up in the 90s as a as a film student, you know, Lone Star and Eight men out and all of those films really had a big impact on me. So I'm excited to get into it with you, my friend.

John Sayles 0:39

Great!

Alex Ferrari 0:40

So first of all, first of all, how did you start this insane journey of being a filmmaker?

John Sayles 0:47

You know, I I started really just telling story. So I certainly grew up watching more TV and movies than I did reading books. Although I did rebuilt books. I did some acting in college and directing of of theater in college, the College I went to didn't have a theater major, and certainly didn't have a film major back in 1970, or whatever it was. There were you know, maybe about four film schools at that time. I didn't go to any of them. And and so I started out, basically having this kind of long distance Jones for wouldn't it be great to make a movie. I didn't know anybody who had ever made a movie or bend in one I didn't know anybody who'd written a book or gotten one published. But I did. I was working just kind of straight jobs and started sending off short stories to magazines. Got one published got another one that the company said, Well, could you expand this into a novel? And so I started as a novelist, I wrote two novels and short story collection. And then a friend of mine who had produced and directed the summer theatre I worked in who I'd gone to college with, said, You know, we know so many, you know, good actors. And I had just started getting work as a screenwriter in Hollywood. Somebody had read one of my short stories. They worked for Roger Corman. He said, Well, let's get this guy and see if you can do anything. And I wrote Bronto for him, which was a very successful new world picture. Then I wrote two other movies for Roger and he was, at that time, a signatory to the Writers Guild. So I had to get paid minimum which was $10,000,which are screenplay.

Alex Ferrari 2:57

Which I'm sure he hate, which I'm sure he hated.

John Sayles 3:01

Yeah, well, wasn't it. He wasn't a signatory to the Directors Guild. So Joe, Dante who directed Parana got $8,000, which was well below the guild minimum at that time. When I had $30,000, in one place at one time, I figured when is this ever going to happen again? My friend who had run the summer theater, I've worked in just said, Let's make a movie. And so I wrote, We turned waka seven is really the only time I've done this where I said, here's how much money I have. Let me write something I can do well, for that budget. Sure. And I, you know, I had some vague idea about what, you know, camera rental of a 16 millimeter camera and all that, you know, very little idea, really, because they weren't books about filmmaking, or YouTube. There was a internet yet. And so it was kind of on the job training. And I had five weeks to shoot. And we rented this old ski lodge near the theater that we had worked in that we had lived in before, which became housing set. In no office. Nothing I shot was more than a five mile radius from that. The movie was full of people who were right around 30, who were good actors, but not quite in the the, you know, right, the actors guild yet. And it was about people turning 30. So it was very much tailored to as I said, what I could do for very little money. I had a crew of seven, who had made commercials in Boston but never a feature before. They had 16 millimeter film equipment. could rent the rest of it. And on the first day, my first shot I get up, not that complicated tracking shot and timed how long it took to, you know, get done. And I decided no more tracking shots. Like the cat, camera, and a little bit of handheld. And we got it made somehow and then got it made. I edited it. Just through a friend of a friend, we got a recommendation to submit it to a couple film festivals. One, the film felt film X Festival, which used to be in Los Angeles, good festival. And then the new directors Festival in New York. And we got into both of those. And this is 1978. There's about five, maybe six independent distributors who they'd watch anything with sprocket holes, you know, right, like, the head of the company would watch anything with sprocket holes, because there were so little competition. And so we had about three companies bidding for it. We went with a guy who, who owned theatres in Seattle, Randy Finley, he had a company and then he realized he really didn't know anything about east of the Mississippi. So he went partners with another of the bidders on the film, Ben Baron Holtz, who had a company in New York, and then kind of invented the midnight movie, and you know, had a long track record. And together, they got the movie of pretty good distribution. It, we never made that many prints, we probably had 10 prints and all. And we would play an era, you know, a region and then move those prints to another region and move those prints to another region. Didn't do TV advertising, we do a lot of radio advertising. And word of mouth. And in those days off Hollywood theater, if they were doing well with a movie, they just keep it on the screen.

Alex Ferrari 7:04

Yeah, because there was just no competition. There was nothing there was no content, they needed content.

John Sayles 7:09

Yeah. But you would get in a situation like in Chicago. The the Art Theater in those days was the Biograph, which is where John Dillinger was shot. And it was the only show in town for a non Hollywood movie in Chicago. And I remember my year what was called My brilliant career was doing very, very well. So we were in a holding pattern over Chicago until that started to do less business. And then we came in and did seven or eight weeks, which you just don't get to do anymore.

Alex Ferrari 7:44

Yeah, it was a whole other world back then. And then also that film got submitted or got into the film registry that the US film and film registry. Is that correct? Eventually, yeah, yeah. That's what was I mean, seriously, I mean,

John Sayles 7:57

It's a phenomenon, I think, you know, just kind of, you know, because it was kind of the beginning of the American independence movement. Yeah. All theaters showing American independent films starring nobody you ever heard of

Alex Ferrari 8:11

Right! It was it was the it was it was the Sundance movement. Before there was Sundance. It was kind of like what the nine

John Sayles 8:16

Years before Sundance I actually went to something called with a USA that the Park City Film Festival, okay. The became the USA Film Festival. It was basically the Denver Film Festival, I think was the pensez or ran Telluride for years. ran a couple years. And then Redford just decided to do Sundance, which, you know, step things up another notch.

Alex Ferrari 8:42

Yeah, I mean, I came up in the time of the 90s, which was the birth on like, I was telling, Rick Linklater when he was on the show was like, you know, you go, you're kind of like the birth of the 90s independent film movement. He's like, Yeah, there was John before me. There was many other others before me, I go, Yeah, but the Sundance phenomenon, which is the overnight superstar, like the lottery tickets, like, like Rick and like Robert Rodriguez and Kevin Smith, and at burns. And Steven Soderbergh. The list goes on and on Spike Lee, these kind of guys. That was that moment in time. But yeah, I always like to always let people know, especially filmmakers to understand, like, if you were able to just make a movie in the 70s and 80s. If you finished it, it was sold. Like it didn't matter if it was good or bad.

John Sayles 9:31

It didn't necessarily get that much screen time. Right? Well, but somebody would try to put it on the screen and see if it worked. Yeah, exactly.

Alex Ferrari 9:40

Now, I wanted to go back real quick to your Roger Corman days because is there anyone who did not go through Roger Corman? I mean,

John Sayles 9:48

A lot of people went through it and in their careers never really just, you know, took off, right. But Roger always said I'm suspicious of anybody who works for me more than twice. already good. They've probably moved on. But an awful lot of people did you know before me Francis Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich and Jonathan Demi and Jonathan Kaplan, and a whole slew

Alex Ferrari 10:15

Oh, God,it just the list goes on. The list goes on and on. And now what was it? So out of all the time that you were working with John, I mean, excuse me, we were working with Roger. I mean, you did Purana. Which, you know, is it's a classic. And then did you write also alligator?

John Sayles 10:31

I did alligator, which was not for Roger, but with with Lewis T, who I had done, lady in red. With, and then I did the howling with Joe Dante, but that was not a new world. I did battle be on the star. Yes, that's the one up there, which is, you know, James Cameron ended up being made head of the production line. Yeah, he met smarter who did the, you know, the soundtrack for it? And, you know, so we said, the great thing about working there is that Roger, if he paid you for a screenplay, he, he wasn't gonna waste that he's gonna make that movie. So for somebody to write three screenplays and see them on a screen within a year, that's very rare in Hollywood,

Alex Ferrari 11:17

That's insane. It is insane to actually be able to do that.

John Sayles 11:20

And then for the directors as well. He, he basically said, here's the deal, here's your budget, here's your script, don't go over, you know, make the best movie you can. And you know, some of them were good, and some of them less than good. And as he said, you know, if you're any good, you won't have to work for me again. So Howard was there when I was, you know, working there. And Rhonda to I think he started one and then he directed another for Roger, and then he moved.

Alex Ferrari 11:53

Right, exactly. And I have to ask you, what was the biggest takeaway you had from working with Roger at that time in your career? Like, what was that lesson? That you're like, Okay, I'm gonna take this with me. And I, you and I used it and you use it throughout your career.

John Sayles 12:07

Certainly, it was getting to go to the set, I got to go to the set of Pirana down in Texas for a couple days, and it was to see what couldn't be done with just hard work and creativity. And what do you need to draw money? And there's definitely, you know, a party in between those two. And so, you know, Joe, Dante had $800,000 to make this Jaws spin off. And he did what he could, you know, and some things cost money and and some he just fudged it and found a way around the expense and still did a good job.

Alex Ferrari 12:55

Right. I think if I remember Pirana, it was there was there was some of the Pirana shown, but I think he used a lot of the Spielberg book of saying, like, let's just see the aftermath. As opposed to always seeing the Pirana hit.

John Sayles 13:07

No Joe had started in the editing room, man, I'm cutting trailers and then cutting features for Roger. There's a lot of fast cutting. Yes, it's about this many frames, if you remember. Then and then they don't look good anymore. You know, but but with really good sound effects and good music by delta, non Joe. You know, Joe made it work?

Alex Ferrari 13:33

Yeah, no question. Now, you've also edited many things. And not all of you have edited all.

John Sayles 13:39

I work with editors of all three of my team films.

Alex Ferrari 13:43

Right, exactly. So and you edited a lot of them yourselves. Do you find that filmmakers or directors specifically, what is what what is the value you think being an editor brings to being a director because I've also been a cutter I started off as a cutter, and I man, it makes my life a lot easier on set, because I'm like, I'm already editing it while I'm shooting. Do you find that as well?

John Sayles 14:04

Yeah. I mean, absolutely. Certainly, if you're working on a tight budget, and you're doing a little bit of coverage, you know, I've got what I need. You know, so I often enacted were saying, wait a minute, we only get three takes and I blew a line, every take and I say yes, but you blew a different line, your take, and Your acting was good. And you didn't break character. And you know, I've got this cover, and we're moving on. I think the other thing is, you know, you don't need to edit your own movies, but I think it's a good experience to have had you learn, oh, it would have been nice to have a close up of this kind of way. Have a look left once, just in case, you know. So you you learn more about coverage when you're editing, especially when you're editing something You know, I'm always cursing direct the director when I'm in the editing room and saying, what did he get? He didn't get cut away the dog or whatever. Yeah, well learn that stuff, you know. And then the next time out, you cover things a little bit better, and not necessarily hosing things down. It's, you know, something very specific. Well, we'll maybe get me out of a problem in the editing room later. And I'm going to get that specific thing. Right now.

Alex Ferrari 15:29

I think you can never have too many cutaways. Never have too many cutaways.

John Sayles 15:33

I've also done movies where I, you know, I have done lots of master shots, sure, like 789 minute long master shots, and the things what Master shots, if you're really going to get the crew into it, you have to commit to them. You know, they hate it, when they see you stop and do some little bit of coverage. Because why are they busting their balls?

Alex Ferrari 15:55

Fighting the movement?

John Sayles 15:56

Yeah, well, that stuff. And so you know, when I do those, I really commit to Sure, and you'll build them up and rehearse them and everything. And then, and then the great thing about that, in your editing period is you come to that scene and you cut the slice off, and you just cut eight minutes and go to the beach.

Alex Ferrari 16:15

You know it? That's it? That is if you're when you're able to pull off one of those long takes, you're just like, oh, great, that was a great, it was an easy cut, it was eight minutes of the movie I don't have to worry about now.

John Sayles 16:25

It's wonderful. We that's the morning, eight minutes is a great board.

Alex Ferrari 16:29

Oh, absolutely. No, no question. Now, um, is it? Is it true, I read somewhere that you did a lot of acting and writing assignments to kind of support the directing aspect of it or to have freedom to do your own things? Is that kind of true?

John Sayles 16:46

Well, no, I that's how I make a living. You know, on my movies, I've a little better than broken even over the years, you know, because I have invested in my own movies, okay. And very often, the Directors Guild and Writers Guild very nicely have said, well, if you're investing your own money, you don't have to pay yourself upfront. If the movie makes money, then you pay yourself out back in some ways I do. And sometimes I you know, don't get to that point. I don't get paid, you know, I only I act for scale. So, you know, my acting is not going to finance anything. But I make a living as a screenwriter for hire. And that's, that's usually the money that I have, if I have to invest in my own project, to be one of investors in my own project, just stuff that I've built over the years, you know, as a screenwriter for hire. Now, you know, I've written over 100 screenplays between my own movies and other movies, probably 4550 of them have been made. So I do get residuals. And that's a nice income when you you have a fallow period and you don't get new work. You know you you've got some money coming in from those residuals. The howling does very well around Halloween.

Alex Ferrari 18:05

Yes, it does. But you're but you also do a lot of Script doctoring as well.

John Sayles 18:10

Well, not really doctoring. I do a lot of rewrites. Yeah, I've occasionally done doctoring. I think twice in my life, I've done something where they said, Can you just punch up this character? Right? You know, or you can you run this through one time, and that's gonna be it. Generally, though, I'm given a script. They say this isn't working, maybe they have an idea of what direction to go to. And then they just say, well take it from there. So something like the howling, you know, I had it, they gave me a script, and they said, you know, keep the werewolves keep the title. Go, and that was fine. You know, and I didn't have much time to do it. And, you know, that was good also, because then you don't get rewritten a million times by committees. You know, it's always nice to, to jump on the bus when it's about to go over the cliff because they're always can do anything to put the brakes on. You know, they're happy about it. That's, I think, you know, if you're not willing to bet on yourself, I know Mel Gibson has done it a couple times. John Cassavetes used to work on his house, you know, to get movies made. And you know, so I, I don't love the fact that I ended up investing in my old movies, but I, I do it when I have.

Alex Ferrari 19:33

But the game but the game has changed so much over the years in regards to investing in your movies and making money with your movies. I mean, back like you said, 70s 80s, even 90s and early 2000s, there was something called DVD. There was something called foreign pre sales. There was a bunch of that kind of stuff, where in today's world, it's so much harder for you to generate revenue from a film just because of the gluttony of content out there. I mean, you came up at a time when there was inability to do that. I think it's much, much, much harder now, from my experience in talking to filmmakers making.

John Sayles 20:09

You know, there's not as much of an audience going to non Hollywood films, right. You know, even before COVID You know, that was kind of hard traceable cash. I remember when Steven Soderbergh was the president of the Directors Guild, he had a study done. And it was something like 2% or less of directors income was coming from their movies being shown on computers. And higher and higher percentage of the people watching their movies, were watching them on the computer. Sure. And so, you know, he was just basically saying, you know, the internet had not really been monetized for filmmakers. And now that more and more movies are made for things like Amazon and network, Netflix, where they go into that thing. And who knows, you know, it's not money is not passing hands individually on that movie. How do you know, you know, you know, you get paid whatever they paid you to do it? Or are to hand it over? And then you just don't know.

Alex Ferrari 21:21

Yeah, exactly. There was that leak a few weeks ago about that they they paid for squid games, I think $21 million dollars, but it's been seen by 180 million people. So if you try to monetize, I mean, can you imagine I mean, that's a huge, but we don't get those numbers. So you're right. And I'd argue that the internet still hasn't been really, it's not really built to monetize for filmmakers. Now, either. It's getting better, but it's not where it's still, it's not the old days,

John Sayles 21:49

Something existed like this. In I'm in ASCAP and because I occasionally write lyrics for songs in our movies. And in the early days of ASCAP, they just sampled a certain number of stations, this before computers, and so if you just played on on eclectic stations, you might get nothing. Even though your your your thing was, you know, playing here and there, you got nothing. And Michael Jackson got everything, you know, what if that was playing everywhere? Now, almost every outlet that plays music is on computer and their playlist is trackable. So people are actually doing a little bit better if they're if they're getting any play time at all. But it's it's still, you know, the Michael Jackson equivalent is getting most of the money. But you're getting something is just that there's so much out there that it's it's diluted so many times that that ideal thing where you take something a person goes and sees it, they pay money, and that money goes directly to you. There's not that direct chain and was never that direct. There were like, five little things in between you and those dollars. Sure. Um, but oh, it's it's like it's all on the cloud. And who knows how that money's gonna flow back to you the filmmaker?

Alex Ferrari 23:22

Yeah. Now when you I mean, you've written like you said, over 100 scripts, at this point in your career? How do you start the process? Do you start if you're doing an original script? Do you start with character? Do you start with plot? How do you how do you start the process,

John Sayles 23:37

Umm, I usually start with a combination of characters and plot, you know, so for me, it's, it's a character or characters in a really interesting difficult situation. And it may be a life or death situation, it may be a moral situation, it may be a life change situation, but that situation in those characters interests me. And then I start, you know, very, actually, two or three times in the last couple years, I've done this, where I'll be being flown out to to Los Angeles, or find myself out these days to have a meeting or something. And in that six hours, um, I have an idea for a movie. And what I'll do is I'll just write all the scene headings, and then like a one line of what happens in that scene. And by the time I get there, I have maybe 20 pages of seeing headings, which is like an outline for a movie. And it's got, you know, this, that it goes to this and then it goes to this and then it goes to this and these are the places and this is kind of what happens with it. And I'll look that over and generally I'll just start filling it in. Now as I fill it in, I'm adding characters on you know, going into depth with those characters. Sometimes Sometimes I have to stop and do research on It may be something big, it may just be okay. What kind of weapons would they use? Right? You know, I'm sure the, you know Homeland Security high on their list. Oh, yeah, right. Right there. You know, he's pulling up the White House again.

Alex Ferrari 25:15

Google how to blow up White House. Not a good.

John Sayles 25:21

But But yeah, it kind of the plot and character come together, I write very fast. So I write a draft of a screenplay in about three weeks. Wow. And then generally, if I'm lucky and working on something else, and I go work on that, and then they come back to it. Or even if I'm not, I'll just do something else for a week or two. And, and the way my head works, when I come back, it's like, who wrote this and recognize it. And so then you can really be much more critical when you're looking at it and trying to make it better. Everyone wants I was like, geez, that's pretty good. It's like, Ooh, wow, that's brutal. Working on there.

Alex Ferrari 26:04

No, I had the exact same experience. Sometimes when I was when I'm writing my book, sometimes I'll, I'll look at it. I'll like who wrote this, like, I'll just go the next thing like who wrote this? isn't that bad? You just don't even read, you don't even recognize it. I always I always like to ask screenwriters and high performer high performance individuals? Where do you believe, you know, when you're writing? Do you? Do you like, tap into that? Are you going to flow? Like the flow state? Are you tapping into something? When you're writing when you when you're sitting down? Right, like the Muse that, you know, the old idea of the Muse showing up? What is that thing? And do you know how to get to it pretty easily for yourself? Or does it is it hard?

John Sayles 26:47

You know, I, I still write novels. I've got a novel coming out late next year, that's like, 100 page novel, wow. And you know, you do you do movies for a while, and you don't do anything for a while. And then you decide, okay, I'm going to, I'm going to try to do that thing as a novel. And, and there's like, for me about 10 minutes of just don't remember how to do this, and then I get interested in the story. And then oh, this could happen, and oh, this could happen. And oh, this connects with something else. And then you're into it. And so there really is like a zone, and I'm locked in, then I've never really had that, you know, writer's block thing, which is, and part of it is that I'm willing to just kind of, you know, keep moving and say better writing here, I'll work on that out later. I don't know how to do this scene yet. So I'm gonna go to the next scene and write that, and then maybe I'll know when I come back. So you just keep going forward, but I get into the zone pretty easily. And, and, you know, I like writing. So it's fun, you know, to see where the story is gonna go and know that, you know, I could connect this with this and all that, there's a lot of problem solving to it. So there's, there's, you know, there's kind of almost like a crossword puzzle kind of thing. It's not, it's already there, you're creating it. But to make those connections and to build one thing on another, and then you always get to rewrite. Right, though, so I don't know too much about anything being perfect while I'm doing it, because I know, I'm gonna go over it. And, you know, half of the writing that I've done for hire has been rewriting other people's stuff. And I'm always happy to keep the good stuff. You heard the structure, if that's what they want me to keep? You know, I'm not shy about, you know, that's a great line. I'm keeping it I don't care if I wrote it.

Alex Ferrari 28:48

Right now it Do you you've also directed some amazing, some amazing actors over the years, and I've noticed that you kept a lot of the same actors, you kept working with the same actors again, and again. Do you have any advice for filmmakers directing actors? How do you pull a performance when an actor is not going exactly where you want to go?

John Sayles 29:11

Well, you know, some of it, some of it's just trust. And that's one of the reasons to work with people that you've worked with before, right? You know, you know, I have, I tend to have big tasks. And you know, you've got 20 People in the cast, and eight of them are known to you, you've worked with them before. That's like, oh, I don't have to juggle 20 balls, I can put eight of them on the floor. And I only have 12 right now to figure out how you're there to help the actor and the actor is there to help you, you know, it should be mutual. And so the first thing you want to do is really talked to that actor beforehand about who's this character, and I mean, before you get to this app, so I write a bio for every character, even if The person has three lines, I write a bio for them, the bio may be longer than their, their screen appearances. You know, four pages is the most I've ever gone with anything. And it might be like, a short story or something like that. And that's the stuff that's not necessarily in the script, you know, how long have you been married? No, where's your life going right now, all those kinds of things that would be helpful that an actor would have to make up themselves, I want to make those things up and steer them in the direction, then you talk to the actor, you know, usually on the phone, in my case, because I can't afford to bring people in for rehearsals before I start the shoot. Um, so you know, you're on the same page. And then on the day, really, what you want to do is just set the scene for the scene that they're going to be in, and then watch what the actor is going to do. That's where you start. Now, that may not be where you finish, but what you want to do when you know, you're hiring actors, because they're good. I think they're right for the plot. Every once in a while I've had an actor who really interpreted without changing the line, something very differently than what I've imagined. And I've liked it better than what I imagined. That's why you want at least that first tape to see where they're going to go with, you know, and then you start to say, and, you know, you know, you do these things incrementally, is okay, let's bring it more in this direction. Because, you know, all you're really, you know, giving actors is direction, you're not teaching them how to act, you're directing them. So let's move in this direction, let's move in the direction where you are really, really pissed off, and you're working really hard not to show. Okay, and then you go to the other actor who's in the scene and saying, you know, what you really love to do you like to make this person break. They're cool. Yeah, you just so you know, just give them a little needle on this. And then you can have a different dynamic, you know, so, you know, it's, I always say it's like, especially in two people seeing it's like being the corner man, for both fighters, the other woman and say, you know, hit with a jab and said, Well, he throws that jab at him really good, you know, so you can change that dynamic each time and get something interesting. You have to handicap actors very quickly. Some actors are wonderful on their first take, right? Their instincts are great, their energy is all there. And then they start to complicate or lose energy. Those are actors, you want to have technical things all really, really ready to go. And probably the cameras pointing at them first. So they're not stale, from having the camera behind them, you know, for six or seven tapes, you know, and then you have other actors who actually, you know, maybe they surround their lines, you know, they get closer every time well, maybe that's the person who you're over their shoulder for four takes before you turn the camera on them. And they, they've had time to walk around in the scanner, the character a little bit, you handicap those things, the same thing with information. Some actors want a lot of information. I've had actors just say, give me a line reading, I don't care, I'll make up my own. And then other actors, it's if you complete a sentence there, I've stopped that, you know, and so what you really want to do is, is think of like three words, that's going to get them in the direction that you want to get them. And they'll they'll take it from there. Because anything else kind of gets in the way of their process. So you figure those things, you know, you can ask an actor before you start, how do you like to work? And they will tell you, that's not always actually how they like to work.

Alex Ferrari 33:48

That's how they think you want them to work?

John Sayles 33:50

Yeah. Well, like to think about themselves is working, but when you find out what's really going to be helpful for them. Um, you know, an actor's having a hard time with lines. A lot of what you have to do is depressurize that, you know, if it's an older actor, you say, you know, do you like to work with cue cards? No big deal. We'll just write them up. You know, usually they'll say no, and sometimes they'll say, Yes, you know, you wish they had said yes earlier, if they're at that point in their career, but what you have to do is defuse that, because when when people get tense, they get even worse at their lives. And so, you know, you just say we'll do this one line at a time if we have to, just you know, you know, keep your focus and stay in character. And don't, don't always say cut just you know, now, especially that we're not shooting on film, and we don't roll out after 10 minutes. Um, you can just keep rolling and keep the thing very, very kind of loose and, you know, easy and so much of my direction then is not you blue aligned. As the actor knows, they blew the line. It's, yeah, yeah, you'll get the line, really, you know, this time concentrate on this feeling, or this undertone, or this physical movement or whatever. And, and so that the criticism and the direction is not underlining the fact that they're blowing their lines, it's about the acting, it's about the character, to keep them in character. It's, you know, it's, it's a lot of work. But as you, you know, you really want to, you're there to help the actors. And if you've got people you've worked with before, and they're good at it, sometimes they can really help you with that other actor. I've taken actors aside and said, Okay, I need a little bit more out of this guy, exaggerate your performance, I promise you, we are behind you, you know, you can overact to beat the band on this one, and it camera's not going to see it. Or I'm not gonna cut out any bad stuff anyway, so you can just kind of, you know, to the scenery in this one and see what you can get out of this person. I work with a young kid in, in Mexico once, and I was working with Federico loopiness, a wonderful, large intending actor. And I said, Well, I'm going to do this thing on Danny. Because he's getting, you know, like, like, a lot of kids, he thinks, Okay, my job is to learn my lines in order. And so I'm waiting for my cue for the next line. And, and I want them to learn the line. So he's a character and when he's asked a question, he answered that question. And so I just said to Danny, you know, you know, Federico is kind of old, and he probably won't blow his lines, but he may say them out of order. So you're gonna really have to be on your toes. And really, no, you know, what your listen to what he's saying, you know, because he may owe you a curve, and you're gonna have to, but answer what he you know, don't do your things in order. And then every once a while, I had Federico mess one up, you know, and the kid was so on his toes that he was really active. Instead of saying he wasn't dead, turn his turn my turn his monitor,

Alex Ferrari 37:21

It, don't you find that sometimes with actors, you have to just kind of get them out of their own head, sometimes, especially, I mean, experienced actors are different. But when you have young actors like that, they're getting in their head so much, that you just have to take them out. And that's a brilliant technique you just laid out, that's a brilliant technique to get into the out of his own head.

John Sayles 37:39

Yeah, I don't like to call them non actors, I like to call them new actors, right? So very often with them, it's what I'll do with my body, you know, because all of a sudden, they're thinking about it, you know, and I'll give them something to do. And I'll actually be specific about so I'll say, Okay, you're me, you know, he's gonna come and question about a year and be hanging up laundry. Um, but the really important thing is, put all the blue stuff up first, and then put the red stuff up, and then put the yellow stuff up. And then I'll have the props people mix them all up. So while while they're like doing the laundry, they can't just be, you know, mind dad grabbing something and putting it up, they've got to look for the blue, they've got to really do something. Um, they probably will not blow their lines, but they're going to have that little lack of, you know, like a person whose attention is divided. Like, I'm doing my laundry here. This guy just showed up and he's asking me a question. I got I got a job here, buddy. takes them out of them worrying about what do I do with my hands? And you know, you know, how much how much time do I I take before I answer him and anything like that, and what, how much eye contact and everything like that they got a job to do. And that really I find helps. Occasionally I'll just, I'll just say look, you know, we're shooting you from here. I want you to be on I want you to be even more uncomfortable. Lift up your like left leg and balance on your right. Okay, let's shoot. A No. And all of a sudden the person is trying, but you know, make sure you don't look shaky hills, a person is really concentrating on something. And it gives them a sub, you know, a subtext of these they're worried about something here, what they're worried about falling over. But to the camera is just like what's going on with this person? You know, they're there answering the questions, but something else is on them.

Alex Ferrari 39:52

That's brilliant, that those those all those all those techniques are going to help everyone was taking notes on that one. Because those are things that you only learn from Doing only learn from going again and again and again and again and being on set so many times,

John Sayles 40:05

And having been an actor, you know, and that to knowing what helps you as an actor, you know, especially day players because that mostly the acting I've done in movies in other people's movies has been as a stapler, the you know, the important thing to know, when you're a day player is you walk on the set, and the crew looks at you as a liability is this guy going to kill us today we're gonna be here all day, you know, we're gonna get behind, you know, and that once you're done, you are furniture, when you when you're, you're wrapped, get out of the way, because they've got stuff to do, you know, and so you're there for a very, very specific thing. And, you know, as a day player, when the main things you have to do is just remember this movies about me. That's my character's idea. I'm going to go on, you know, the camera may stay there with that idiot, but I'm, I'm the star of this movie, and I have to play it that way. But in the real world, I'm firming.

Alex Ferrari 41:15

No, you're right.

John Sayles 41:17

I'm that the stars gonna get to get into character and all that kind of shit. I've got to be really be ready with this thing. And, you know, just open yourself up to the script supervisor should help you and the director who can help you and just say anything else you need, you know, and be as generous to the other actor who's in the scene with you as as you can be done. That day player thing is I really value people who can come in and just nail a scene. And, and and goodbye.

Alex Ferrari 41:51

Did you ever have one of those times that you acted in someone else's project? Did the director pull you aside and go, John, how do you? What do you think about this scene? How do you think I should shoot this?

John Sayles 42:04

Well, no, during it, I was in a movie with that bear trend. tavini, I directed in Louisiana, and John Goodman and Tommy Lee Jones were in it. And nobody pulled me aside while I was acting, but they started fighting over the cut, the director and the producer and the actor kind of went in different directions. So all of a sudden, you're asking me to look at the thing. And so guys, I would do a date player. I can't tell you. And finally I just I said okay, I'll watch both of the cuts. And I'll tell you exactly what i All of you exactly what I thought of them. And I thought, you know, these are both valid ways to cut this movie. And, you know, Breck Thrones is more poetic. And the one that Tommy Lee and the producer made, you know, it makes more sense, probably literal sense for an American audience. And they did what is rare, which is the smart thing, which is they finally decided in Europe, it was bare trans cop in the United States, that was the producer. And now and so they could all, you know, say nice things about the movie when they did their their press tour. Yeah. But, you know, really, you really, when you're acting in somebody else's movie, you're really trying to help them make their day and make the scene come alive. Right? You know. And, you know, a couple times I've been on, like, I wrote a TV show years and years and years ago, and called Shannon's deal. And I came to do a part on in an episode. And it was like, you know, the fifth episode or something like that. And every single actor who had a recurring part came to me, because they knew that I was the head writer on this thing is that, you know, in Episode Seven, they got me into chicken soup. You know, my character wouldn't wear a chicken suit. Guy, you know, I'm the writer. I'm not the producer. But, you know, you have to figure that they figured, I'm talking to God here, right apart, and to a certain extent, is good for actors to butter up the writer in a TV series. Absolutely. You know, good writers, when they when they when they see an actor start to take off or do something interesting. You know, especially for a series that you're trying to stretch into another season. It's like, Oh, I could hang something on that. You know, we could go somewhere with that guy.

Alex Ferrari 44:36

Now, as a director, I mean, I think every director, whoever who's ever directed a movie, there's always that day in production where everything is falling down around them. The world is coming. Though the world is coming to an end. Either you are at that moment going. I'm a fraud. This is horrible. I'm not going to make my day the sun is going down. What was that moment for you in any of your films? And how did you overcome it?

John Sayles 45:05

Yeah, I mean, we, you know, there was a scene in my second movie Leanna where I just said, We're never going to leave this room. Terminating angel is is like that boom, well movie, and because just light would break and somebody's stomach would blowing right in the middle of a scene. And it just, it just wasn't happening. And I did that. And then same thing happened when we were making Lonestar there was a walking talk between Chris Cooper and Liz Pena, alongside the real Bravo. And it just wasn't good. And both times I said, you know, I think I have to rethink this scene, when you shoot this again, and let's move on. And so you just get out of there, and then you have time to rethink it. And sometimes it's, I'm not going to change anything, but I'm going to appear to change things. So you move, you move the camera back, and you put a longer lens on, and you got the same image. But it seems like you've done something different, you know, you know, I up the angle, you know, let's, let's change this thing. And so it's not on the actors, if they're part of the problem. And it doesn't, it doesn't seem stale. So I read blocked the walk and talk slightly. I move some lines around. Then I made like one good kind of a line and a transposition or something. And I remember I, I got there. This is, you know, down on the border, near Eagle Pass, and I got there. I skipped lunch that day. And I went and I, I laid down on a hot rock and thought about how am I going to restage this thing, so the actors feel like they're doing something totally knew from what we did yesterday. And I started hearing the crew arrived and everything I looked up in the sky, and there were five buzzards circling rock, you know. And then, and then I explained it to them, as you know, you know, I think I figured this out. And I've changed some lines here and a slight change in the blocking. And it was new enough that the actors came at it with a totally different energy. And we did two texts, and we were gone. So so a lot of it is just kind of just change the change the dynamic a little bit. Sometimes it just means everybody's tired, and you should go home. Important to know that you're just gonna do two hours of bad work, why not go home and get two hours of decent sleep, and then you'll catch up at some point. Sometimes it's that, you know, something has gone stale. A hard thing for movie actors that you don't have in theater, because I've acted in theater, too, is that when you, you've got to make everything seem new. And it's not an order. And often when you're in trouble in a scene, just because you're playing the end of the scene, because you know what happens at the beginning of the scene. Right? And that's hard to forget that on take 12th Especially if it's kind of a long scene, well, whereas if you if you change the dynamic or come back another day, you have more energy for it, you know, and if it's different, it's different. It's not the same scene doesn't have to be that much different. It's not the same scene, and all of a sudden, you find another way to do it, and it comes along a little bit.

Alex Ferrari 48:56

Did you ever use that old editors trick where you if you have a producer that you have to appease? Or studio that you have to appease that you throw in a red herring in the cut to have them have something that's so obviously not supposed to be there where they can go, oh, I can I have oh, I yeah, you need to change that and seeing six and you're like, Oh, thank you for seeing that. But you knew that that was gonna come out anyway.

John Sayles 49:23

Yeah, you know, I really only had had that battle once when I was making baby two with Paramount and they just decided they wanted a high school comedy halfway through the shooting. And it wasn't written to be a high school comedy. It was never going to be Porky's or Fast Times at Ridgemont High. But I really just said, I'm just going to make the movie. I'm going to cut the movie that I think is the best movie and then we're gonna fight over and I got out of the editing room. Ah, they get their cut. They test marketed it their test market at one point worse than my, my cut. So they very grudgingly gave me back the movie to cut. And, you know, there were a couple things they done, you know, just kind of physical cuts that I liked. And I kept, that was a throw everything else went back to what I had before. But I didn't want to, I didn't want to test them with that kind of stuff, there wasn't a censorship problem, which I think you can get with with sex and violence, you can get censorship problem. And then sometimes it doesn't make sense to just like, let's just hit him with everything. And so in such shock and awe, that if we, if we cut things out, leave the four that we really want, you know, they'll be happy and think that they've won the battle. And you know, people would do that with the MPAA as well as they leave a couple things in that they could concede. Okay, you forced me to give up my favorite shot. You know, when it's a fair shot at all? I haven't really had to do that kind of gamesmanship. What I do, I do do is when I do screenings, I don't do the the fill out a form. Did you like this? Did you not like this thing? That's so subjective. My questions are all Did you understand this? Because that's when you lose an audience's right, don't understand what things are confusing. Right? You know, and that's usually the feedback I get from an audience that that means the most and makes me you know, change cuts. And then also just kind of sitting with my back to the screen and watching an audience watch it and feel them reacting to the picture. No. And does this seem like they're treading water a little bit? Should? Should we get to something quicker? Yeah. You know, it's good to have, you know, people who did not work on the movie, see it, but people who you think are gonna like it, or could like it. The problem with those invited screenings that they did is, you know, they did a test of baby, it's you. And there was a rumor going on, you know, in Paramus, or wherever it was that it was a Burt Reynolds picture. Well, some of our bad numbers were probably because people were pissed because Burt Reynolds never showed up. The son of

Alex Ferrari 52:22

What's Burt Reynolds gonna show up in this movie. Now, in your film, Lone Star, I honestly when I saw Lone Star I was I probably was in film school, and, or right before it, and I, for the first time really saw the transitions you did to transfer time. I remember like, it was all in the same shot. So you'd start off in the bar, and you would pan over and then it was in the past. And it was done so masterfully. Where did you get the inspiration for those shots? Because I've, I mean, I've seen Coppola do it and not with time as much I thought, like Dracula and and Tucker and things like that. But yours was the first time I really kind of noticed that mastery in that in that scene transition. Did you get inspired from somebody? Or did you come up with that?

John Sayles 53:08

No, I'd seen you know, tricky master shots before and stuff like that. Um, I think there might have been a couple of Italian movies, you might do that once in a film or what?

Alex Ferrari 53:20

Sure.

John Sayles 53:22

But I actually, like those kinds of transitions. I remember. I wrote the screenplay for cleaner, the cave bear. Yeah, there, Hannah might, you know, and originally it was going to be a TV movie. And in the TV movie, you had like seven commercial breaks. And so when there was going to be, you know, a time montage, you could get rid of the time montage, and just your cut to a commercial break. And, you know, so you know, we see some little blonde girl, get saved from a saber toothed tiger that, you know, scratches her thigh, you know, and leaves climax on her on her thigh. You cut from that to the commercials. And then, you know, seven minutes later, you cut to Darryl Hannah's thigh, and it's got this scar on it, and you pan up to her faces Carolina, and that many years have passed, you know? So I often thought about transitions and how different they are in a feature. They're different than in a TV movie. And, you know, and what a transition does as far as time is concerned. And so I was interested in how do I do a transition, where I underline the fact that we're living with the past. It's not this is now that was then it's, this is now and then is right on our shoulders, then is is, you know, loading the dice with everything we do now. And that's the kind of town that we're in. And so I thought up the shots where we would go from, you know, you know, present day, back 27 years or whatever it was 17 years, I forget how many years it was, and without a cut, and then you sit with your, your production designer, and your lighting guy and your grip department and you figure this shit out. And it's really fun for them to do. Oh, yeah, no, it's like, when you do this, you know, oh, well, you know, when we come back, the place has to be redesigned. So we have to have stuff that we can just stick on the walls and stick on the columns really quickly. And, you know, Cliff, James is a big guy, and he's in his 70s, he's not going to be able to get out of that chair quickly enough. So we're going to have to have two grips, lift him in the chair up and run ahead of the camera and get them

Alex Ferrari 55:55

Those are the best. I love this shots

John Sayles 55:57

You know, the other ones where we're going to start on two cops walking down the street being harried by these two civilian ladies. And then as they go behind the car that they're going to get into our camera operator is going to step onto a platform on the side of the cop car that's has to be slid in after the driver gets in. So that we need to give them two lines there for that to happen. When the guy slides in, he shuts the door, we hold on the guy on the other side, still standing up. But by the time we come down and look through the window, there's this platform, our DP has, you know, operator has stepped up on it, and they can drive away with them. And now we've got a moving to shot without a cut. And then they can get out and we can follow them into a building. You know, well, those for a grip department, it's so much fun, there's guys sliding under cars with Makita drills in you know, and pulling the trigger in between lines and stuff like that. And, you know, putting magnets on with with light units on the front of the car, because you saw the car first naked, and it's got to have all this rigging on it, you know, and you know, that's maybe half a morning of rehearsal, just for all that mechanic stuff. And then you start working the actors in and we we'd make three takes, and then you know, it's lunchtime, and you're done. There. There's so much fun and satisfying for our crew and for the actors and stuff. And there's a there's a nice kind of energy and spirit for the actors that comes with them. Um, there's the challenge, you know, you're doing a nine minute scene, and you come in at 830. And you have three lines. You don't want to blow off.

Alex Ferrari 58:01

Oh my god, yeah,

John Sayles 58:02

That guy who had the last line who was lying because you've been waiting for so long, you know, you know, and we just do another one. And you'll be better this time.

Alex Ferrari 58:16

And it's lovely. You go You You better be better this time. Now, um, I have to ask you, you know, you also got to direct a young up and coming musician back in the 80s. By the name of Bruce Springsteen. How did you get hooked up with Bruce and like, direct some of the most iconic music videos of the day of that of that era,

John Sayles 58:40

Kind of evolved. When we did baby, it's you, which was, you know, set in in Trenton, New Jersey, and, you know, during the 60s, and even though is the music that we used wasn't from that era. There were four songs that I really felt like iconically belonged in that movie, just as in they're not coming from jukeboxes or anything. So they're not, we're not pretending they were written then they're kind of the the more authorial music in the movie. And we just contacted his management and said, Look, we'd love to use these songs. We're going to cut the movie together, put the songs in, you get to see it, if you hate it, we have backups. If you like it, we'll make a deal. You know. And then as it turned out, they liked the movie. They liked the way the music was, was was used, and were very generous with their half of the music rights label performances. They own the publishing and they were very generous with the publishing which was, you know, great because, you know, we could buy some other songs. So we had that contact. Then Maggie frenzy who are married to and has produced a bunch of mine. Movies, her sister did a PBS movie, a dance movie? She's a choreographer that your Springsteen music and the thing with PBS is you can use anybody's music. And it's free. Because it's public, you know, television. So if you saw the the Vietnam series that burns dead, every hit of the of the six,

Alex Ferrari 1:00:21

You're absolutely right. I never thought about that.

John Sayles 1:00:25

Oh, wait, you know, 28 seconds of Rolling Stones in the background, because you don't have to pay for

Alex Ferrari 1:00:30

Oh my god, I never even thought about that.

John Sayles 1:00:33

You know, you could finance a country for you know what, what he has to pay for some of his soundtracks. But for Peasy PBS, it's just like, you want it, you got it. And so, Marta was able to get that movie to Bruce. And through that, we kind of met Bruce and the people who, you know, kind of ran his business forum. And I think it was right after the Dancing in the Dark video. He wanted to do Born in the USA kind of gritty, and they call us up and say, Hey, I do Grady. Any had, you know, so did the three videos for Bruce. And they were, you know, basically his ideas. And I certainly had, they weren't big budgets, but it was certainly more money than I'd ever had to make two and a half minutes of film, short class, I got to cut Springsteen, music, you know, in the at the end of the day, so they were really fun to do. A little difficult in the case of glory days, in that he had just gotten married, and was more famous than anybody on the planet for, you know, about three months. And so I remember, we were driving out to where we're going to do the intro on a baseball field. And there's like, you know, a rock and roll station helicopter following us reporting. We're just in case we need more people hanging out and in screwing up our shot. But there were fun. And, and, you know, the E Street Band was fun. For the first one, we got to film for concerts. So we get to see for Bruce Springsteen, live concerts are close every night, you know, so that there was some continuity in it. But that was kind of when you know, rock videos, I think there is an important role that they did for you know, upcoming directors. So many upcoming directors cut their teeth on those with a real budget with cranes and fog and all this shit that can't afford

Alex Ferrari 1:02:45

Techno cranes and stuff like that. Yeah,

John Sayles 1:02:47

Yeah. You know, creative things with them. So that was a that was a nice era, I think for upcoming filmmakers,

Alex Ferrari 1:02:56

Especially the 90s when like the finishers and Michael Bay and Quan Spike Jones. And, I mean, you look at some of those old Fincher like Aerosmith. Like Janie's Got a Gun. It's a masterwork. I mean, he had all the money in the world, it was insane.

John Sayles 1:03:10

Yeah, and in many of them are kind of like very small movies, right? Kind of diable cut out, you know, and they had to look good, you know, and they were it was very competitive, those kinds of things. And the record companies still kind of existed and still have money to spend on those things

Alex Ferrari 1:03:29

God so much money in the 90s.

John Sayles 1:03:31

And then it disappeared fairly quickly.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:33

Yeah, I remember working in Miami when I was coming up as an editor and working like two $300,000 budget music videos on like B and C level. X, not like a levels would be getting half million million million and a half. It was in since say it was a different time.

John Sayles 1:03:51

Feature films in my world? Absolutely.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:53

Absolutely.

John Sayles 1:03:54

Really. I'll make a feature.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:56

Absolutely. No question. Now, is there any advice you wish you would have heard at the beginning of your career?

John Sayles 1:04:03

Yeah, I think I could have used about a week of film school. Just for some technical things that would have been helpful. On my first movie, I wish I trusted my instincts a little bit more. My crew having having, you know, late 70s shooting commercials, everything was kind of rock steady and very clean. And the shaking cam thing on MTV hadn't started yet. And I wanted a more sound documentary look to it and handheld. And I would have been happy to have almost the whole movie handheld. And they just Oh no, it's gonna look terrible. People are gonna get sick. It's gonna be shaky. Right? When just to have some movement in the movie. There are two sequences in Secaucus seven, one where these guys are playing basketball and they work a thing out, and another where the whole bunch of more playing volleyball, and then a third one where they're playing charades. And I got the operator to handhold. And it turned out he was a great handheld operator he had worked for, forget the guy's name, who made all the scheme films, Warren Miller, why and he, my operator used to ski down a hill and duck his head between his legs and shoot upside down and backwards as people ski down a hill behind him. Wow, that guy and he used to shoot the Dartmouth football games handheld, you know, so he was a great handheld operator, he just, he just didn't think it belonged in a feature movie, because that's the commercial feature world that he was thinking of. Sure. So I think some is, look, you know, trust your instincts, and then live with them. So if your instincts are wrong, then you go in the editing room and you know, you you try to fix things, but and then I think it would also just be don't say cut so quickly.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:16

Oh, god. Yeah, that's one of the best piece of advice I heard some I forgot who it was like, when your

John Sayles 1:06:22

First one because we were running we were running out of 16 millimeter we were up in New Hampshire. We didn't want to over you know, buy stock because you couldn't really get back or anything like that. So it came on the on the Trailways bus twice a week. We just kind of parceled it out. And so I was always really you know, cut right on the thing because I don't I you know, if I've got two minutes left on that 10 minute reel, you know, I got a I got a, you know, minute and 52 seconds seen that I can get in there or take that I can get in there and I didn't want to blow that and half shortens. But so often, I caught a little too close, or there was a nice reaction from an actor. You know, it is the great thing about digital now which is you let it go. I saw I think it was Tom Hanks and Matt, what's his name on a show who had done a Clint Eastwood movie and they still were so so you know because cleaning wasted you know, notoriously low key on a set and you know, instead of action it's kind of okay, let's let's get into this guys. And they were saying that they had to get used to eastward saying when he was done with something Okay, that's enough of that which is better than clot too quickly. But there is a nice thing which is that sometimes what you get at the very end it may not even be for that scene. Yes reaction. It could be your face because they hated their cake. But that face can work.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:07

Yeah, yeah, I heard that same advice somewhere someone said when you're about to do cut wait five seconds just hold it for five more seconds even when you want to cut because you just never know and I've been in the editing room so many times I've grabbed a look a movement something from exactly what you just said an actor hating their take or something going like oh, and it's perfect for another scene.

John Sayles 1:08:29

I learned I also learned early doing conversations especially to just say okay keep going stay in character okay look left at the guy now look right at something done and and every once in a while you need that that right look you know or that left look and you have to flip something and have you know the

Alex Ferrari 1:09:00

The logo it digitally remove? Yeah. Now I'm gonna ask you a few questions asked all my guests. What advice would you give a filmmaker trying to break into the business today?

John Sayles 1:09:13

I would say you know, you're a filmmaker, make a film. Um, do and importantly, do something that you think you can do? Well, so let's say you wrote a nice 90 minutes feature and it can it can it can star you know, new actors or you know, kind of a mixed bag of people were pretty good actors are very new edit or whatever. See if you can go out and make that movie for your money. You know, with the best, the best equipment you can get. And then call it a rehearsal and look at it and if there is 20 minutes that you think is great after you cut it together. You You have that to start showing around. You may get to make that very movie, again, with ideal people, some of the same, some different, whatever. And you've already had a great practice, run. But really learn learn what works, what you did well, and that's what you show. But I think the best way now to get discovered is not you know, necessarily knowing somebody or, you know, showing, you know, oh, my film school teacher thought I was wonderful, you know, which is to have something to show behind, and then and then you're going to have to give it away. Yeah, you have to put it online, you know, and try to, you know, get it seen, wherever you can. Volunteer, you know, if you got to film school near you, if you're an actor, you volunteer to be in all those movies. Um, you know, I got Chris Cooper for making one who had never been in the movie before he done quite a bit of theater. Because he was in my production office coordinators, student film at NYU, Nancy Savoca, had used Chris Cooper. And when he was just an acting student in New York, she's you got to see this guy. You know, he volunteered, you only met Nancy. And he did a good job in her film. And she really liked working with him. And she talked him up. So as an actor, you know, just find out who's making movies and say, you know, here I am. I'm not the guild yet. I'm giving it away. You know? Um,

Alex Ferrari 1:11:38

Yeah. And you've and it worked out with you and Chris Christie, he's on okay for himself over the years.

John Sayles 1:11:42

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. You know, and is, you know, if I hadn't discovered him, somebody else would have been, in those days, I somehow got away with making a, you know, $3.2 million movie with an actor who asked to lead who'd never been in a movie before.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:00

That's insanity. Yeah, yeah, that's insanity. That would never happen in a million years now. It just doesn't. Yeah.

John Sayles 1:12:06

Well, I mean, I think, you know, think about, you know, you've written a bunch of scripts, what's the one that you could do for almost no money? With friends, and it would be watchable, when the ideal would be watchable? Or is there a scene from it? That that that shows, you know, some part of your directing that you think is really good? Or somewhere you're writing that thing? You know, you just do that sing? It? It's, it's doable? No, it used to be that would cost you money. Even on an amateur level, it would cost you money, you have to buy film stock. And right now, you I was 16, at least equipment. No, it does not have to cost you any money. And here's the thing, though, about that, which is you and your collaborators. The hardest thing for you to survive and stay friends will be success.

Alex Ferrari 1:13:01

That's great advice,

John Sayles 1:13:03

A cut, you know, I've seen this happen a bunch of times, you know, when a movie comes out of nowhere and gets to be a success, really, only the director may be an actor, and may be the producer, but probably not will get any attention. And they really are going to have to grab on to whatever that is and get a deal for another movie or whatever. And, and other people may be jettisoned, you know, which is a why I say on your first movie, you can pay people nothing. On your second movie, you either have to pay people something or get new friends who are also just starting out. So it's a big deal. But also, just understand that, you know, credit doesn't go to the team. Very few lactams have stayed together for more than one picture. So, so really think beyond be honest with each other of what you're getting out of this is the experience. You know, I know people who had a big success at Sundance, and one of the great things they were able to do is they said, We are renting a condo, anybody who worked on the picture if you can get your ass here, come and you're invited to the party and you're invited to the movie and and that's it, we can afford to bring you there. And that that may be it that may be a reward, you know, is the fun of that party and having worked on something that's good.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:36

And how about for screenwriters. I mean, because you've just written so much about screenwriting is trying to come in and break in today.

John Sayles 1:14:42

Yeah, if you're only a screenwriter and you went to film school, I'm trying to buddy up to some of the people we think we're really interesting directors. You know, an awful lot of people Coming through film school, I think they have to be writer directors. I'm a writer, director, there are few writer directors. There's a writer directors, there's a lot of really good directors who have a good story sense, but they're not writers, right? They need. And if you're a screenwriter, that's who you want to hook up with somebody who think he really has a nice visual style, who has interesting ideas, who has a good story sense. And then you say up once a material to try your hand on. And once again, it might only be a scene but hook up with those people. It's a really hard thing as as a screenwriter to break in, as I said, Well, I broke in by having written two novels and a short story collection and introduction to a film agent, right. Somebody read one of my short stories, and then, you know, and when I wrote a screenplay, I had only read one screenplay. Somebody gave me a copy of William Goldman's screenplay for The Stepford Wives. So I knew, because there weren't, there weren't film writing books, then. So I at least knew. And I read it, and I realized, I could do that. For, you know, it's very simple screenplay. It's, you know, it's kind of a no brainer, you know, he said, what I could do that, you know, so it actually is good for my confidence of the this guy gets a half a million dollars for running things through his typewriter, you know, I could great premise, blah. But you know, just just kind of knowing that, and then we really having this thing is, okay, I'm writing for a reader. And so this thing has to read, exciting, it has to have the rhythm, the rhythm of a movie. And so you really have to think about your whitespace and your Yes, popping things up and cross cutting, and not too much description, you know, but my favorite example of great discretion is Raymond Chandler story, where he has this line. The detective goes to somebody's sleazy office, and he says, he gave me a drink of warm gin and a dirty glass. That's the only description of the office. That's all you need. If you can find that equivalent, you've got one little slug line, you know, don't be saying no. And then we see this, and we see that and you that's for the, you know, production, you can get it down to those one or two lines, you know, and, and maybe it's funny, or whatever, and keep the rhythm of the thing going. So that it reads like a house on fire, if that's the rhythm of those screenplays. But you know, this is the movie right now. And then later on the directors gonna say, well, I need to know more about this, this, this and this, and this, that's after you've got the green light, you can put all that stuff in. But the but the first thing you're writing is a selling document. And that's just got to just be exciting to read and have a page turning quality.

Alex Ferrari 1:18:23

What is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film industry or in life?

John Sayles 1:18:28

You can't predict the future. And there's a thing called the Monte Carlo fallacy, and gambling, which is basically okay, you're playing roulette, just because the ball went on the black 10 times in a row doesn't mean that it's more likely to go on the white the next spin the month, it's still a little less than 5050. Because there's, there's, you know, the one, the one greenspace. So, when you're not getting any work, that doesn't mean you'll never get any work again. And while you are getting work, that doesn't mean you're always going to get work. That there that there was so much luck involved in it, no matter what your talents. Um, there's, you know, I know actors who have had terrible time because they did good work and three movies in a row and those movies didn't get released. Right? Like they died, or Oh, does that actor have like a substance abuse problem? What happened to that actor? Well, they disappeared because the movies didn't get released, not because the actor did bad work, you know, and then that was over a year and a half, two year period. It's just like they disappeared. Well, they're off the list. That can happen with writers as well. So you you really have to just keep slogging away at it and not let it get you down, you know, you have in terms of life, you have to be realistic. And if you're gay, I've been lucky. And I've gotten to the point where I've made a living as a writer for a long time now, pretty much rapid interrupted by maybe a year or two of no work. But enough money coming in that I didn't have to take a different kind of job. If you're younger, if you have kids, you may have to take another kind of job, right? And then you have to really make that decision of what kind of job can I take, where I still have the energy and willpower to go home and crank at the, you know, the keyboard for a couple hours. Whereas I really, you know, doing that, when I when I was first sending out short stories, I found that when I worked in a sausage factory, or a plastic factory, I could come home and I could work for three or four hours. No, no human contact, just noise, you know, and, you know, kind of wrote, you know, routine, you know, motions and physical work, but but nothing mental. When I worked in hospitals and had to deal with people, I was too exhausted to work at all, and they paid. So probably the non human contact Job was a better one, to also have a career as a writer than one with a lot of human contact. Don't be a social worker.

Alex Ferrari 1:21:36

No, no way. Um, is there a lesson that you learned from your what is the lesson you learned from your biggest failure in life and in the film industry?

John Sayles 1:21:47

Um, I would say that the movie is gonna last for a long, long time. And that the compromises that you're willing to make with a movie are gonna haunt you, if you you feel you sold your own movie out? Yep. And so it cost quite a bit career wise, maybe. And, you know, my hair should still be blonde. Uh, I hung in and you know, on baby, it's you and I said, Look, you know, you financed this movie, it belongs to you, I'm just not going to put my name on it, unless it's a cop that I believe in. And finally, it was one of those deals where they said, they kind of threw it back at me and said, Okay, cut it the way you want to. And then pretty much told people do not do any work on this movie, we're going to let it escape, we're not going to release it. And so that was kind of a vindictive release of the movie. This is so counterproductive. So kind of productive. You know, that happens on it. You know, it especially happens when new people take over a studio and killed cups. You know, in this case, it was like they had some other successes. And you know, they just wanted to get this thing off their hands and not look bad. But the movies still good. And I still liked the movie. So I don't have to kind of say, Oh, God, I wish I had held out. You know, and you know, and so that was in some ways it was a failure because the communication broke down and round, as well as it should have. On the other hand, we turned out the way that I thought it should. Good.

Alex Ferrari 1:23:35

And last question three of your favorite films of all time.

John Sayles 1:23:40

Ah, yo, Jimbo,

Alex Ferrari 1:23:42

Nice.

John Sayles 1:23:45

You know, just just kind of the music, the everything, the rhythm, everything. camera angles, just really fun to watch again and again. Treasure of Sierra Madre. Just a great Hollywood movie. You know, by certainly independent spirited director, John, it was you know, he got himself down to Mexico. And where are from, you know, you're probing and made a really, really good movie and drank a lot of tequila, I'm sure. And, and it and it plays like an independent movie to me. Yeah. And has a real kind of soul to it. And then to women, which is Vittorio De Sica movie with Seville aren yes is just really, really moving. World War Two movie. And it's kind of my introduction to European cinema. I didn't see a movie with subtitles until I was in college. I just saw you know, foreign movies on TV, if they played them all, and if they weren't in English, language they were dumped. So I saw the dub diversion first with commercials and it's still, you know, got me to cry, you know, and, you know, just the kind of depth of humanity of it, you know, beautiful performances. And just SICA had a really, really human touch. So, you know, those three movies you know, to me just kind of got me interested. How could you? Could you actually because most movies weren't like that, right? Like, then mainstream movies and everything like that, but those were ones that really jumped out at me when I saw them.

Alex Ferrari 1:25:39

And when when's your next movie? When are we gonna see another John Sayles movie?

John Sayles 1:25:43

Why would I get one financed? Like most green screen writer directors, I have? three maybe four. Just just add money. You know, we're working on a couple now. I'm actually I got to work with Doug Trumbull effects, who also did Silent Running and brainstorm. We're working together on something that we would co direct it kind of big science fiction thing I've got that we shoot in Mexico. I've got a kind of one location bar room movie with John Cusack and Chicago that you know,

Alex Ferrari 1:26:26