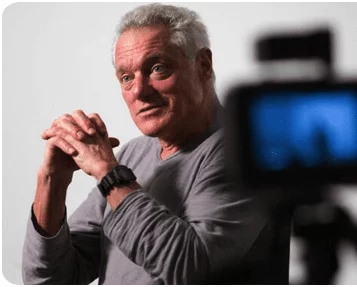

What if the greatest stories of our lives are the ones we never meant to write? On today’s episode, we welcome Steven Bernstein, a man whose journey through the world of cinema has been anything but predictable. A writer at heart, a cinematographer by accident, and a director by destiny, his career is a living testament to the art of surrendering to the unknown. From his early days at the BBC to the sets of Hollywood blockbusters, his story unfolds like an unplanned masterpiece—one that ultimately brought him full circle, back to the thing he always loved: writing.

In this profound conversation, Steven Bernstein recounts his journey from philosophy student to award-winning cinematographer, where his love of storytelling found an unexpected home behind the lens. He speaks of the curious ways life moves us, sometimes against our best-laid plans. “You tend to go with those things that are providing you income,” he muses, reflecting on how a passion for writing gave way to cinematography, leading him to films like Monster, Like Water for Chocolate, and Scary Movie 2. Yet, even as he shaped light and shadow for some of cinema’s most striking images, the writer within him never faded.

There is an undeniable poetry in the way Bernstein describes his work. He doesn’t just shoot a film; he composes it, layering meaning through framing, movement, and light. Every choice—a dolly push, a backlight, an asymmetrical composition—whispers something to the audience. It’s a language beyond words, one that he speaks fluently. “Everything to do with film is a language,” he explains. “And like any language, it’s made up of two parts: that which we present and that which we mean.”

His journey back to writing was not an easy one. After years of crafting imagery for others, he took a leap into directing his own films, starting with Decoding Annie Parker. It was a lesson in risk and resilience. At one point, he spent five years in poverty, refusing to return to the safety of cinematography. “If you hold out for the dream, maybe you achieve it,” he says. It is a stark reminder that the artist’s path is often one of sacrifice, but those who persist find themselves richer in ways beyond money.

Yet, Bernstein also understands the tension between art and commerce. Filmmaking is an expensive endeavor, and investors want guarantees. He describes the struggle of balancing creative vision with financial expectations, a dance between inspiration and limitation. And yet, some of the greatest filmmakers—Terry Malick, the Coen Brothers, Charlie Kaufman—have defied convention, proving that the most resonant stories often break the rules.

The conversation moves to the nature of collaboration, the unspoken alchemy that happens on a film set when everyone is in sync. He recalls moments from Monster, where the crew, sensing the gravity of a scene, chose to remain completely silent, whispering only when necessary. It was an unspoken agreement, an offering to the art being created. “It was one of the most magical moments I remember in any film I’ve ever worked on,” he recalls. It is a glimpse into the rare, sacred spaces where true storytelling happens—not in the scripts, but in the spaces between them.

Right-click here to download the MP3

Alex Ferrari 0:07

Enjoy today's episode with guest host Dave Bullis.

Dave Bullis 0:38

I have my next guest, he has been the director of cinematography for such films as monster directed by Patty Jenkins, who just directed Wonder Woman, Kicking and Screaming, directed by Noah Baumbach, and Like Water for Chocolate, he's also been the director of cinematography for comedies like the Water Boy, Half Baked, Scary Movie 2, White Chicks. And he's on action films like Swat. And he also wrote a film a textbook called film production. And his latest films decoding Annie Parker and dominion have included actors like Aaron Paul, John Malkovich, Helen Hunt, just to name a few. And currently, he's actually teaching some really cool online and offline seminars, which, again, I'll link to in the show notes. We're gonna talk about a lot of really cool stuff on this podcast episode with guest Steven Bernstein. So Steven, just to get started, you know, you've done a lot of really amazing work. You've done a lot of work as a cinematographer, you know, starting in, you know, the the late 80s, and you've done all these wonderful projects. And I wanted to ask how you got to that point. I mean, that's sort of the, the impetus to a lot of interviews, and a lot of, you know, people who've, who've been able to really ascend up that, that proverbial ladder is, you know, how did you get to that point? So what I want to ask you, Steve is, did you just to sort of start this off? Did you go to film school, you know, to be a cinematographer, or did you do have a or did you have a completely different sort of entry way into this industry?

Steven Bernstein 2:15

A completely different entry way. I had wanted to be a writer and read or majored in a philosophy at university. When I came out, there were various job opportunities of different types, one of which was at the BBC training program, which I enrolled in and studied there as a writer, director, researcher, and worked in long form documentary, great because it allowed me to travel a great deal, which was an interest of mine then and I Got to go to China, Hong Kong, Philippines, Vietnam, South America, South Africa during apartheid, what was then Rhodesia, later became Zimbabwe. So a lot of adventures, a lot of really interesting shoots, and some great experiences, but not really that satisfying, and not as it turned out, my calling, I came back to London and continued working at the BBC. About the time that music videos became of interest, the first few music videos would be produced, and I got to shoot a few of those, and soon I was in demand, not as a director or as a writer, but as a what was called, then a lighting cameraman, a cinematographer, and shot a lot of really interesting music videos for some really, then very big bands in the in the 80s, Eurythmics and so. On, and that led to interest from others, and got into commercials. Worked with the great Tony Kaye, did some really important commercials with him, some of which won the Cong, Golden Lion da D award, and then I was kind of on the map. Still, my intention always had been to be a writer. So it's funny the way life works in that you tend to go with those things that are providing you income. Inevitably, you can have good intentions, but overheads, life expenses being what they are, you do what you have to do. So I was shooting, enjoying it, particularly the music videos and the commercials, but I was still writing plays, films, short films, some of which appeared on Channel Four in the UK. Some got on the stage in London, but really nothing that provided me any sort of success. And then along came Like Water for Chocolate, my friend Gabrielle barista, and had been offered the work completing that movie, which had run into a little bit of trouble, and he couldn't do it. So they asked me to go to Mexico and finish the film, which I did. It's a big hit in America, the highest foreign highest grossing foreign language film of all time to date. And I then came to America to see if there was work to be had here. And that led to all those studio films, those comedies with Adam Sandler, with the weigh ins and so on. And that in turn led to my meeting now the great Noah Baumbach, and starting an independent films in America. And that in turn led to Monster. So I've tried to compress what is now seeming a very long career into a very short period of time, but a happy series of accidents, doing what I never intended to do, ending up at a place I never intended to come to, and somehow working my way back towards my first intention.

Dave Bullis 7:04

Yeah, you know. And it's funny how it all sort of comes forth full circle, right? You start off with one intention, you have. You find yourself in all these new situations, but you took advantage of those situations, and, you know, you turn them all into opportunities. And now you're, you know, and now we're going, you're going back to writing. And I think there's something poetic in that, because I think as when we as filmmakers and and whether we're writers or directors, when we start our careers, you know, we have an idea of what it's going to be. And usually everyone has an idea that it's going to be. You know, you're going to make a movie at 22 you're going to win Sundance, you're going to make a million dollars, and then you're gonna move to Hollywood. And, you know, Steve, it doesn't really work out that way. It's a lot of zig zags towards that sort of path. And, you know, and it's just a that's why I do this podcast, because there's so many interesting stories like yours, where it's not just one way. In fact, with all these episodes of so many different ways of doing things, but, but the point I'm trying to make is, you know that that's the thing about the intention that we have, and how life sort of throws out all these obstacles, and how we respond to them, and how we you how we respond to them really dictates, you know, what course our life is going to go on.

Steven Bernstein 8:19

I think you're absolutely right, and it goes to great complexity that life offers us, which is, do we earn $1 do we do what makes us the maximum amount of profit all the time, or do we hold on to an individual dream and simply wait it out? It's very interesting, because I've done both. When I started, I made no apology to say that was kind of an opportunist. I was taking what was offered to me. And look, it was a fun ride. I got to, again, travel a lot, both first at the BBC and then doing music videos. I got to meet really interesting people, particularly in the 80s, and the bands we were dealing with and the concerts we were doing and the videos we were doing, all very, very exciting, but really it was the work that was offered, and I took advantage of that later when I went to make my first film at Decoding Annie Parker, I had seen other people try to make that same transition to director, and they tried to keep their day job as it were, and none of them succeeded. So I resolved that I would give up everything to do with cinematography. I would give up anything to do that didn't directly point me towards directing, and that's what I did. And sadly, decoding did not happen quickly. We were promised money, that money went away. We were promised other money. That money went away, and I spent nearly five years unemployed and went through all my savings and most of my possessions, and was in abject poverty on the day we finally got funded, and then went to shooting. So both courses interesting, I think ultimately, the latter one more painful. You sacrifice a great deal, but if you hold out for the dream, maybe you achieve it.

Dave Bullis 10:22

Yeah, and, you know, holding out for the dream. It's kind of like Sid Hague, you know, he, people once asked him about his acting career, and he had actually given up. He actually, you know, sort of went away for a long while, because he said every, every role that he was offered was basically he became in as a man with a gun. He came into the door holding a gun, or he came in, you know, he's already in the room with the gun. And what happened was he came back because, you know, he actually liked it and, and finally, he said, You know, I realize now he's in movies with Tarantino and Robert and Rob Zombie. And he said, You know, it's like Winston Churchill said, never quit. Never quit, never quit.

Steven Bernstein 11:00

I think that's absolutely right. And there's a great example of this that we know I mean Patty Jenkins, a dear friend of mine. Patty was the director of Monster, which I shot. The story is interesting both how our relationship began and how Patty built her career. I was shooting the big second unit on SWAT, 21 cameras, tons of effects. We're spending millions of dollars blowing up the front of the library in Los Angeles, crashing planes, shooting rockets into cars. It was everything I thought I dreamt of when I was a young cinematographer. And then after four months of that, I got a call from Clark Peterson, the producer of monster, and known for years the film was in some trouble in Florida, and he asked if I would read the script, speak to the first time director, and consider leaving SWAT and coming to Florida to shoot monster, and I read the script. I thought was great. I spoke to patty on the phone, and was struck by her intelligence, her sensitivity, her command of the subject matter and of herself. I just sensed that she would be a great leader. And agreed, and came down at 1/20 of what I was getting paid on SWAT arrived in Florida to this tiny little film that was underfunded, under equipped and in real trouble, and we began working together. And for me, it was a epiphany, because I saw people of absolute and genuine integrity, completely believing in the art they were undertaking to create. And Charlize was self sacrificing, and the role was agonizing and difficult for her, but she pushed through, as did patty and then, of course, monster, when we finished it, no one would buy it, which a lot of people don't know, Blockbuster would be the only people that would put forward a not very good offer, which was taken with the proviso the film would get a very limited theatrical release. And amazing to them, and I guess to kind of everybody, the film got spectacular reviews in the papers. Patty ended up along with Charlize on Charlie Rose, and then we went to Berlin, where Charlize won the Silver Lion, then a Silver Bear rather than the Golden Globe, then the Oscar, of course, and the rest is kind of legend. Right after that, Patty was offered pretty much everything from studios, and you or I, or I don't mean to speak for you, let's say someone like me would have taken that opportunity work on a studio, be paid a million or 2 million. I know what she's offered, but a lot. But Patty had a vision of what she wanted to do, and remarkably, and this goes to her character. She said, No, these aren't the films that I want to do. She wanted to a film about Chuck Yeager. She had some other projects that were interesting to her, and she was going to hold out, as I did on my film, for what she was waiting for and what she believed she'd be adept at doing and achieving. And waited and waited. Did some television pilots, very successful ones, the killing which she did a great job on. And then along came a Wonder Woman. And Patty said, yeah, here's a strong woman with a voice that I find interesting, a subject matter that I've always liked. I'm gonna make this film. And what did it do this weekend? I mean, it was spectacular. And it's not just the box office revenue we generated, look at the reviews it's getting. So that's Patty's remarkable. And I think in structural and structural journey,

Dave Bullis 14:54

You know, I once met Kane Hotter, and Kane actually said the best. Actor. Actress that he ever worked with was Charlize Theron, and he said she was, not only is she was she very nice to everybody, with no airs whatsoever, but he said when Nick time came, she was absolutely amazing every single take, every single day. He's like, she never did a bad take, not one time. And when you see something like Monster, it's, you know, because Charlize is a beautiful woman, and then, you know, She transformed herself with all the makeup, and she really became that role. You know, I had on a couple different acting coaches, and they said that was the secret of acting, is that you don't act like like you're a person. You are that person.

Steven Bernstein 15:41

I think that's spot on. And, you know, look, I have the remarkable distinction of being the one cinematographer that managed to make Charlize Theron look bad. So it's very, very special. And I'm very proud of myself, and Charlize was very proud of me, but she and I worked very hard on making her look bad. One that goes to her great courage. Because, look, an actress's beauty is in part, her commodity in Hollywood. And the fact that Charlize, like Patty before her, had such an integrity of vision that she was willing to sacrifice her commodity value from the pursuit of art goes to the person that she is. And secondly, you're absolutely right about the quality of Charlize performance, and she does this strange hybrid of method acting and more classical approaches. She knows the material. She's always off page. She gets it completely. She intellectually understands and engaged is with the topic and knows her character and the character's arc, but in the moment, she is a method actor, she is completely engaged. And as your acting coach, a person that you interviewed, said she became that character, we believe she was that person completely. You know, there's a remarkable thing that happened on Monster one day where there was a key moment when Christina Ricci and Charlie, Sarah, and the two characters were saying goodbye to each other at a train station, and they both had worked their way into this emotional high, this there was a sense of intensity. And if you know film sets, as I'm sure you do the crews, you know, just carry on eating their sandwiches and lying down their track and doing what crews do. But something remarkable happened this day, and the crew just sensed that they wanted to support Christina and Charlize and what they were pursuing. So the crew decided unilaterally not to speak that day, and the crew was communicating with each other with hand signals and with pointing and occasionally a whispered word, but it was dead quiet on that set for the entire sequence, and it was one of the most magical moments I remember in any film I've ever worked on This sense of synergy of all of us working together to support what we felt was the achievement of great art. And I think it facilitated those two performances in that remarkable film.

Dave Bullis 18:13

I mean, and see stories like that are just so interesting to hear. You know, just working with different actors over the years and seeing all the different methods and different approaches. And it's very interesting to see to the crew, you know, responding in that method of recruit, responding and being very, very receptive, and helping Charlize and Christina Ricci and doing something like that. It's just very interesting to me when, because, because you mean, you've been, you've seen a lot of sets, Steve, where the crew ends up in the crew and the cast, they end up becoming like a family, because you're spending, you know, days into weeks, into months, making this film. And it almost becomes like a child for everybody, you know, and and everyone's a team player, and they all want to see, you know, what's best for this project that they've worked for so long on.

Steven Bernstein 19:00

I think you're exactly right. And this is the thing I think that's most attractive about film, is you do acquire a family for a few months, or a few weeks, or one of the films I did in India for a year, where you're all under great pressure, but you're all mutually dependent on each other, and you're isolated from the rest of the world, and you feel somehow special, not special, as in entitled, but that somehow the way you are mediating the world is different from the way you mediate the world in the civilian or Non film world. So the camaraderie and friendships that are built on film sets, to me, are still singular, and my closest friends all come from film and the most intense experiences in my life, generally have occurred on film sets. And I must tell you, there's never been a film that I've worked on. However bad the film may have been where it wasn't, followed, at least for me, by a profound depression that would last days or weeks. And I think I speak for virtually all film crews and actors. When you walk away from your family and just say, Okay, this films done. I'm going back home. Now, home doesn't seem like home. The set was home. And there's a peculiar transition stage, which some people never get over.

Dave Bullis 20:35

You know, you're absolutely right, Steve, I've been on a lot of sets like that where it's almost, you know, it's, I don't want to use this expression, but I will. It's almost like a high. It's almost like this, this feeling, this energy, actually, energy is a better word than it's his energy that you feel. And, you know, you just sort of whenever, especially when everybody is is gelling together, and everyone's there and they're professional, and they're all working together. It's that, you know, you get that feeling and you want to, you know. And when you leave and the project's over, you sort of go home and you're like, What am I going to do now? I guess I better watch Netflix and order pizza, right? It's like, but you want that feeling again, so much.

Steven Bernstein 21:15

No, absolutely right, to the point where it's like, maybe high is better because you're like an addict. You'll be walking down the street and you'll you'll see another film shooting. You sort of wander over thinking that you might be able to pick up on some of that energy. Maybe they'll invite you to lunch, but it's a it's something that you that you absolutely miss when you're not doing it. And listen, that's one of the problems I have when I moved from cinematographer to writer, director and producers. That when I was a cinematographer, I would be doing sometimes two features, sometimes even three a year. I'd be working all the time, and I'd be on those film sets with my, with my friends, with my with my film friend family. When you're a director, when you're a writer, in particular, you're locked in a room, you know, with a computer or with a fountain pen and no friends at all, just writing and writing and writing, and it's not as much fun. I'm down with Dorothy Parker, who said, I love having written. I hate writing. Well, that's, that's kind of my view. I'm very proud of my last script in particular dominion, the one with John Malkovich, and I'm very proud of decoding and Parker and the next one coming up. But still, the process of creating those stories, those scripts, very, very hard and very lonely.

Dave Bullis 22:37

It is a very lonely process. And you know, I wanted to ask Steve, you know, when you've, you know, worked all these years as an accomplished cinematographer, and you, and you go back to your first love, which was writing. As odd as this question sounds, was there any skills that translated? Because I think there was. And here's the one I one skill I think that really translated well. Was you, you will obviously lensing all these wonderful films and like, like Monster. You know, how that you, you know, have, you have that image in your mind. You have that, that sort of mind's eye where you're saying, okay, I can imagine, you know, we're opening up on this mountain range, or, I imagine we're opening up on this sort of dark night, and we can barely see. I imagine that helps a lot with your exposition when you're writing scripts. Because when you're writing, you know, this, these action lines, I imagine they're, they're very, very well told, because obviously you know exactly what it's gonna look like. Because, hey, you're a cinematographer, you know, and you can bring all those years of imagery and seeing all these different things to your script. Am I right or am I? Am I completely off a Steve,

Steven Bernstein 23:46

No, you're spot on. And go to the very essence of my philosophy and understanding of film. What I discovered both from first my reading when I was a student of philosophy, and then later as a writer than as a cinematographer, is that everything to do with film is a language, and we have to understand what a language is. A Language is inevitably made up of two parts, that which we intend to mean and that which we present to create that meaning, or what I think the philosophers called the signifier, that which the audience sees, and the signified that which we mean, the idea that we're trying to present. As a cinematographer, you realize that when you compose a shot in a particular way, you can create a certain feeling in an audience. You can even suggest an idea. When you push a camera forward on a dolly, for example, into a face you're saying to an audience, hey, what this character is about to say or do is important. That's not in a script, but the camera movement is the signifier. The idea of importance is the signified. And then I began analyzing everything I did as a cinematographer, and. As a language. If I light with a backlight, that's the signifier. It's backlight signified mystery or uncertainty, an asymmetrical composition that is the signifier. The signified, possibly a character who's alienated, or a film like wait until dark, a character who's at at risk to edit a shot where you do an extreme close up, then go to a very wide shot where David Lean might have done you're saying, Oh, here's a person in a small little landscape. That's the signifier. The signifier is the insignificance of the human condition, perhaps, or the weakness of that individual at that moment. So when I realize all those things, I realize that everything I put in a written script is again a matter of what I signify and what it means, how it is indicated, and ultimately, what I'm trying to convey to an audience. But I also realized that not everything can be done with the spoken word, that sometimes the most powerful, although the most engratic elements, are not written but implied with the the photographic image. So as I write, I'm always thinking, is it better for the character to say this, or is it better to have the character say very little and imply something simply with a composition or a camera movement, or perhaps with the music or with the rhythm of the editing. If I begin to look at film as I suggest, everybody does, as a series of integrated languages, each with their own set of signifiers and each signifying different things, then I don't feel an obligation to put everything into a dialog, and the dialog can become more economical and more real, and the medium as a whole, integrating all these different processes becomes more effective. Does that make sense?

Dave Bullis 26:50

Oh, it makes perfect sense. You know, as you were describing, you know, your process, I was reminded of, there will be blood and There Will Be Blood the first 20 minutes, you know, there's no, there's no dialog whatsoever. It's a lot of of imagery. It's a lot of, you know, we see Daniel Plainview as he's coming down into that, into that pit, looking for gold. He doesn't find gold. However, he finds oil. And that becomes, he becomes that oil baron, oil tycoon, sociopathic businessman. But that first 20 minutes, there's absolutely no dialog. And when I first saw that movie, I was like, wow, this is a really bold choice. Because, I mean, I imagine the pitch meeting for that you say, if you're a pitch meeting on the first 20 minutes, there's no dialog whatsoever, you know, it's just kind of, you know it, but, but, you know, once you start getting into the movie, it's, I mean, I thought it was absolutely phenomenal. And, I mean, the only reason it lost best picture was because it was up against the No Country for Old Men. And, you know, I which is another movie, very heavy in imagery. Have you? Have you seen either those movies Steven?

Steven Bernstein 27:56

I've seen them both, and loved them both. And I would throw into that mix Terry malix films, Days of Heaven, which was the film, I think that inspired me more than any other to be a cinematographer. You know, malex characters relationship to nature and nature being indifferent. And again, the visceral effect that nature's power, sublime majesty and indifference to us as as living, breathing souls, is important. So in a terry Malik film, all the time, he's cutting away to shots of nature. Again, as you say, a pitch meeting or a description to some investor, you're saying, well, a lot of these shots won't have any obvious meaning or won't advance the story to the next plot point, but it'll be laden with meaning. It will make us understand how indifferent nature and a god or an absent God is to us, and how that should make us potentially feel. And he does that almost exclusively in Days of Heaven, with images, not with dialog, he's combining languages. My feeling is that as a writer and as a director, you don't write your film in spoken language exclusively. You write your film in five different languages like a very skilled linguist, and you combine those together to create meanings and choosing which language to use based on which is most effective and which goes to your audiences sensibilities.

Dave Bullis 29:29

You know, that's very true because, you know, as I've been, because I my first love is writing as well, and when, when I'm writing a screenplay, there's so many different pairs of eyes to sort of look at it through, you know, there's an editor's eyes, there's, there's, you know, the director's eyes. Sometimes you're thinking even in terms of being a producer, you know what I mean, and you're and you you're thinking of all these different of different ways and then, but when you're adding all these layers into your actual writing, you know, you're really, you know, because you're trying to sort of hook the reader, as they say, you know, hook the reader in the first couple of pages, but you have to hook them throughout the whole story. You're trying to always, you know, keep that tension in there. You're trying to figure you're sort of, you know, wearing a lot of different hats. You're doing a lot of different things at the micro and the macro levels.

Steven Bernstein 30:24

You're right, and it's very, very hard, particularly we start talking about producing, because, you know, the person or persons who may determine whether your film gets made may have never made a film, and may have no understanding of cinematic language, of what composition does camera movement. May not have seen a terry Malik film, may not have seen Paul Thomas Anderson film, may not have seen a Coen Brothers film. They may have read McKees book on story and take that template and apply it to your script. And if your script does not use that template. They may feel that your script is a failed one, and this is difficult for all writers and all artists to determine. Do you do what the orthodoxy in our film community suggests, or go giving you a better chance of getting your film made. Or do you protect your singular vision? Be it part of that orthodoxy or not, in the belief that you know better how best to express the ideas you hope to express. It's it's interesting because unlike other art forms, ours is so very expensive that there is a inhibiting element, and that's the one of finance people backing a film want to know their investment is safe, and therefore are looking for absolute metrics to determine what will make your film a good investment for them. They're not interested in your ideas about how to engage an audience viscerally with a composition. They want to know that if the rules of which they may be aware are applied, does that mean your film will succeed, and if it will, will they make more money? And that's a very difficult way to approach filmmaking.

Dave Bullis 32:20

Yeah, yeah, absolutely. A friend of mine, you know, we he and I were just discussing this as well, because, you know, he was a part of a film. The film was already, everything was casted, they were about to shoot, and then suddenly it just all went away. And he said, Dave, it's happened too many times in my career to count. And he says, it just, you know, it happens sometimes where, you know, the money goes away, and then there's been other times where he's been pitching a project for for years and years and years, and it's finally, you get a financier, and you can, you're able to finally find that money. I had seen obvious on this podcast, and he was discussing how he found the money for Dallas Buyers Club. And, you know, it was just one of those things where he had a connection from years ago who was willing to help him out, out of a bind. And it was, you know, one of those cases where your network really is your net worth,

Steven Bernstein 33:11

No question. I mean, you've got to build relationships and contacts, and then you've got to convince people to give you their money to make your film. And again, there's a natural conservative factor in all that, and that they don't want you to take a lot of risk, because they don't know that that will generate money for them necessarily. I mean, we all want the investor who says, just go ahead and make what you believe. But those are rare. Most investors want to get involved and say, Okay, we're giving you this money. What's our best way of guaranteeing this? Are you definitely going to have three acts, and are your plot points going to come on the right pages and all the rest of it? And again, that may or may not be the best way to write a script, but that's what they want, because that's what they've been told is the way to success, and that, as I say, could be very inhibiting for a writer, for creative artists. I'm sure that Terry may like doesn't work to that template, you know, I'm sure Charlie Kaufman doesn't work that template. I'm pretty sure that the Coen brothers don't, and they're some of the most successful, important filmmakers we have working. So these are some of the tough decisions that filmmakers have to make, particularly when you go to finance your film, because you want that money, but you also want to make a great movie.

Dave Bullis 34:26

Yeah, you know, absolutely. And I, you know when we when as because writing is my first love as well. And when we're writing these scripts, sometimes there's a tendency to write with that producers hat, because you're wondering, oh, would this be able to be, you know, will this be too much money? Will I be able to even obtain this, you know, stuff, you know, and that's sort of as I find writing the first dress, we have to kind of sort of brush that aside and just sort of focus on just telling the best single story possible that we can tell. And then later on, when you're maybe doing rewrites, or you're in different meetings, and you can sort of take things out and maybe add things in, you. Yeah, and then sort of, you know, the story sort of evolves, and it kind of ties in with what we were talking about before, where, you know, we set off in the beginning with these expectations that's going to go into a straight line, and then suddenly it's zig zagging all over the map and, and we're, you know, we're, you know, finding these obstacles. And we're, we're trying to turn these obstacles into either they can either set us back, or we can move forward with them.

Steven Bernstein 35:22

You make a great point. And I always try to write my first draft in seven days or less. And there's a reason for that. I call it a slot draft, not a first draft, because what I want to do is write so quickly that I don't have time to think so. First, there's the idea of just an intuitive understanding of character. But also I find that I write to know what I think that if I try to outline before I begin writing, the ideas are only are only notional. I really don't know my characters. I don't know my story that Well, I think I do, and I can try to plot it out, and I can draw all sorts of diagrams and put all sorts of index cards up, but it's not really fully realized. Then, if I take a different approach and simply start writing and say, I'm gonna write 120 pages in seven days, what I discover is that by the time I get to that last page, I have developed an understanding of character. I have developed an understanding of what the narrative should be, and I might even understand some of the subtexts. Then I go back and I begin the real process of writing, which is rewriting, but I couldn't have done that if I tried to make that first draft perfect, and you talked about wearing your producers hat. I think it's essential. I think you made a very good point that when you're writing, you're thinking of nothing except those characters. I don't care how long a dialog scene goes on for, or how outrageous what the characters say are or off, or if they begin in a Proustian fashion, talking about things that have nothing to do with the story at all. Because, in fact, that's what people do in real life, is talk about things that don't necessarily have to do with the advancement of their individual plot. And then when you write that version, that slop version, and look at it, to me, it is the door to all things, you come to an understanding of everything that's important about your film, and then you can put those things, those things in when you go back to rewrite. It's a crazy way of writing, but it works very well for me.

Dave Bullis 37:30

Well, you know, I actually think that's a very good way of writing, because even when I have, you know, started writing stuff in the past, and even now, sometimes when I sit down to start writing, one of two things happens. Number one is you get distracted very easily. I think as this happens to everybody, where you know your phone chimes, or somebody at your door, your friend calls you and says, Hey, Steve, can you help me move? I have to, you know, you take me to the airport. And the second thing is, you have paralysis through analysis where you're sitting at your desk, or wherever you're writing, and suddenly you're just kind of like, oh, wouldn't it be cool if, and you start brainstorming, and you're just, basically, you're just spinning your wheel, so to speak.

Steven Bernstein 38:13

No, exactly, right? And I think this is to me, it was a breakthrough. You know, I was so concerned with failing that I was preventing myself from succeeding. So when I was convinced ultimately that I should write badly, I sat down and wrote the worst script I possibly could, and when I was finished, it was truly terrible, but it pointed the way to a much better script, a script that was so good, this is what I did with dominion, that when I sent it to John Malkovich, he signed up immediately, and it was a low budget film. But John loved the writing of that script, because the dialog seemed so natural and so imaginative to him. If I had written dominion to an outline, my characters would have been speaking to deliver the next plot point, to get to the next subject, to keep the story moving along as it had been outlined. But the way I wrote to many was I simply had my characters talk about things that were important to them, and then went back on the next draft and then imposed a form on that and it was much more natural. The writing was much better, and it's a system that simply works. I say to all writers, and I have a lot of systems that work with me. Don't try to be perfect on the first draft, or don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Simply write as quickly as you possibly can, and then discover what you always meant to say and never realized it.

Dave Bullis 39:47

You know, I like that approach, Steve, where, you know, you gave yourself permission to fail, and you basically said, I'm gonna write the worst possible thing. You know, I was talking to another friend, a colleague of mine Jason Brubaker, And he had a theory about, you know, guys who always talk about making a film. They always, you know, and you've met guys like this, too, Steve, where they're always saying things like, Oh, I have this great idea for a film, you know me and my buddies, blah, blah, blah, but they never actually make it. And the and his theory, Jason's theory, was that the reason they don't make it is because if it does suck, if it is bad, it's a reflection of them as an artist, and it kind of encompasses their entire career in sort of one foul swoop. So if they do write a bad screenplay or make one bad movie. Well, you suck. You're never going to make anything. Do you know what I mean Steve?

Steven Bernstein 40:45

I know exactly what you mean. And I take just the majority of people, not just in film, but in life, most people would rather talk about something than do it. Most people rather criticize others than do it. Those who criticize and don't do are always safe because they can't possibly fail, and can always make clear how superior they are, because they can criticize that which you did look I, when I made dominion, a lot of people said, Oh, well, Stephen, you had trouble finishing it. There was some money issues, etc, all of which were true and those were resolved. But the thing is, I did it. Had I simply not done it and watched others, I don't know if I would have the sense of self that I have. I'm proud of what I've done. I've done it because I've taken risks. But you go to a very important point. If you want to make films, you have to make films, and if you're going to do that, it means you're going to take risks. It means people are going to criticize and ridicule you, and you may even fail. But I'd much rather do and fail than observe and criticize others.

Dave Bullis 41:56

Yeah, and that is beautiful, Steve, because honestly, that is so true. You know, I think we all have somebody in our lives, or we've known somebody that like that in our lives, where they don't want to actually do anything. They may talk a big game, or they constantly criticize what other people are doing and kind of like downplay it in that sort of condescending, sort of very almost like jaded type of attitude where they're like, Oh yeah, that you're gonna make a movie this weekend. That's cool. You know what I mean? They just like they and people like that. You know they never do anything. They're always just sort of criticizing others from the comfort of their couch. You know what I mean? You know what I mean?

Steven Bernstein 42:36

I completely know what you mean. And I look I pay tribute to anyone who takes a risk in their life of any kind. It doesn't mean that we shouldn't sometimes be safe, but you only, I think, have one life. You only have a few opportunities, and when they're presented to you, seize them. I know when we started decoding any Parker, we had spent a long time raising them on it, and I got a little bit of money from India, some from Canada. I was very lucky, and got the tax credit in California. And we were very, very close, within, like, $100,000 what we needed. And the producers all got the phone with each other, and we had to decide what to do. And at that point, Helen, haunted read the script and loved it, and had signed up for a very reasonable sum of money. We had Samantha Morton Helen, of course, won an Oscar. Samantha been nominated for two I had met Aaron Paul, and we had become fast friends. And Aaron Paul, who was at the height of his fame with Breaking Bad, had agreed to do it. Corey Stahl and I had gotten close as he had read the script, and we talked about the evolution of the characters, Rashida Jones, Bradley, Whitford, just this incredible cast we put together. And we were on the phone considering whether we should pull the plug because we didn't have quite enough money, and I ultimately decided that we would go ahead, and I realized it was a huge risk, and we nearly had to shut down. I think we did shut down for a day at the end of a week, and then we went and raised more money, and we managed to finish the film. Went on to win the Sloan award. The Hamptons had won Best Actress for Samantha Morton at Seattle, won the Milan Film Festival, two or three awards there, raised a couple of million dollars for charities, etc. We pulled it off, but there was a moment in that process where we had to decide whether to play it safe or to take a considerable risk. And I think those moments come often in film, because I think it was Hitchcock that once said that drama is life with the boring bits taken out. I would suggest that filmmaking is life with the com bits taken out. So it's a constant state of risk and near hysteria and certain failure. And from that you extract, hopefully. Be a film and a bit of a life.

Dave Bullis 45:03

And, you know, as we talk about your projects, you know, I wanted to ask, you know, when you started to actually go from that cinematographers sort of chair, so to speak, to being a director, you know, what were some of the things that you've picked up? I mean, because you've, you've had a lot of really cool directors, like Patty being the first example I can think of, you know, what were some of the things that you saw these directors were doing when they were talking to actors, or maybe even talking to you as a cinematographer, you know, and talking about, you know, a shot list. And here, and hey, Steven, here's my storyboard, you know, what are some of the the great things that they have done over the years that you sort of took into your projects.

Steven Bernstein 45:42

Well, it wasn't just pat, it was Jon Favreau. I worked with a couple of times, Jon and I are friends. Noah Baumbach, of course, I did three films with Noah Baumbach, which was fantastic. So I had an opportunity to work with lots of Taylor Hackford, of course, I mean, lots of other great directors, and I took something of value from each of them, certainly always grateful to my training at the BBC and always grateful to all my stage actors and what I learned there. But I learned, as I observed, about different management systems, different leadership methodologies and different ways of working with actors and with with crews. Noah and I, before we did both kicking and screaming and Mr. Jealousy and Highball, spent a lot of time prepping we were in Noah's place in in Greenwich Village, and we would go through the entire script, scene by scene, shot by shot, determining not only what we plan to shoot, but why we're shooting, what what the camera would mean. Going back to what I was saying before, about signifier and signified, again, wide shot or closed shot, Noah would show me clips from movies that he liked and said, this is very important to me, could we infuse this sequence with the same feeling from this film? I remember on Mr. Jealousy, he'd been much influenced by the French Nouvelle Vague, so we were using those kind of circular fade outs, and even the music that he chose was very much in that style. But also compositionally, the way the camera moved and the way I lit, it all had to be in the style of the Nouvelle dog. So that was exciting. That's what's so great about a collaborator like Noah, is that he had a very clearly determined vision of not only what his characters were, but stylistically, what he wanted to do. And that would be a great starting place for me to then run with some of my own ideas. I bring him books from painters or from designers or from other filmmakers, photographers for that period. So what about this? What if we did this, like this and so on, and we would integrate some of my ideas into his vision? Patty, I think I told you about her focus very much on actors. How Patty, at the end of every performance, rather than speaking to any of the crew, would drop the headphones and make a beeline directly for the actor. It doesn't matter what anyone else had to say to her. Her first point of contact after a take was those actors to tell them that they had been observed, that they're being protected, that someone is listening. Because that's what actors want most of all, is to know the actor be an experienced director or an experienced director. Those actors want to know that there's someone watching, protecting them, creating a rarefied, safe environment where someone's making sure that their performance is okay, and we'll tell them honestly if it isn't. And Patty really did that to a great degree. Jon Favreau, it was the atmosphere on set. It's kind of like he felt strongly that what happens on set somehow appears on screen. So his sets were fun and light, full of energy, full of comedy, and very, very gentle hand that everyone felt protected and facilitated, and again, that lent itself to what appeared on screen. Taylor Hackford, very, very well prepared and would cover things from every possible angle, knowing that whatever he planned, he knew that he might alter it in the cutting room, and wanted to make sure that he had plenty of material to cut that with. So for me, 30 years of observing some of the best directors in the world was a wonderful education for me, and it informs everything I do now. But was even better educationally, was watching some truly terrible directors get it wrong. And I got to watch that as well, and I'm not going to mention their names, but it helped me to know what not to do. So to accumulate all that knowledge and to be able to walk onto the first feature that I directed knowing what these great directors had done and what the bad directors had done, and what I should or shouldn't do was a huge help to me. It, it still is.

Dave Bullis 50:29

And you, you mentioned this too, Steven, you have 30 years of experience, you know, you you have, you know, started out as a writer. You became this accomplished cinematographer. You've won this just plethora of awards. You got to see all these great, sort of, you know, all these great directors, and all the things that they, they did, right and, and sort of put this all together for your own projects. But I know now you're, you're also doing some seminars, which, you know, you're, you know, gonna, gonna impart all this knowledge, which I think is phenomenal. So could you just, you know, talk a little bit about some of the seminars you have coming up?

Steven Bernstein 51:02

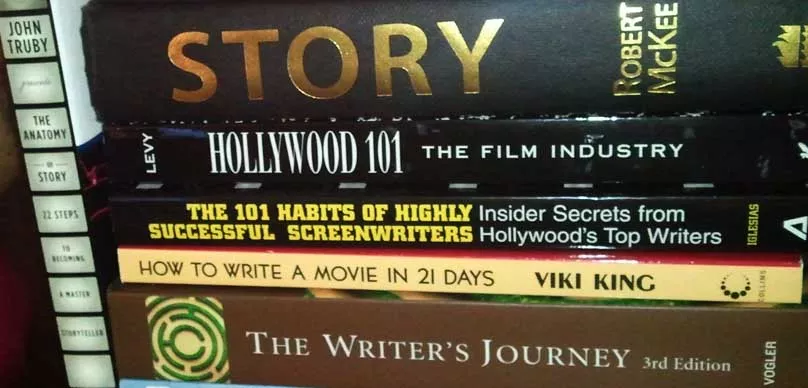

Absolutely, for years, really starting back to right about the time of that the BBC, I began teaching if somebody was a writer and wanted to know something about cinematography, because I had done both those things I was uniquely able to explain and a plain language for a writer or director what a cinematographer does, and then later, when I began directing, I could go into great detail to people about what each below the line crew member did. And when I was producing, I could explain to the investors why we needed money for different things, what the post production crew would be doing, what the on set crew would be doing, why we needed as many makeup people as we needed, and so on. So I was always teaching, and sometimes formally, I taught at the International Film School. In London, I had a film school of my own, and in the UK, in London, I set a film school up in New Brunswick in Canada. I've taught at universities including USC here and others all around the country, and I wrote a book about film production that covers all these things. And then finally, I just thought, you know, I should formalize this and make it available to a lot more people than I've made it available to in the past. So we're taking right now six of my most popular lectures, one on making the independent film, how you actually put together an independent film, how you find the money, how you use that money to shoot the film, how you take it through posts and get into sales and distribution? Another one about for stills photographers, because so many stills photographers have come to me and saying, hey, I want to be a cinematographer. I bought this camera. I've done stills work, but how is cinematography different from photography, and particularly with lighting? So I've done that so many directors and producers want to know about cinematography, how it works, so I I've running a course on cinematography for non cinematographers. And so many actors I've worked with, both on stage and on screen, feel uncomfortable when they first step onto a film set, and I wanted to run a seminar so that actors would know what it's like to come onto a film set, and what the assistant directors do, what the the first assistant directors do, what the the director wants, what the cinematographer wants. So, so all those things very useful for them. And then going back to something you and I talked about a lot in this, in this, in this discussion, is I wanted very much to run a course for writers so they would understand the technical aspects of filmmaking, and they could employ that in their writing to make them better screenwriters. So yeah, we set that up. We've got a website called somebody studios.com you can see all the seminars there. People can sign up, I think that they from the time they sign up, they've got a month to watch the individual seminar they've selected, or they can sign up for multiple ones. And the course has been very successful in the past. Not only do I teach the course, but then afterwards, I have a Q and A and we keep the lines open, and we make sure people have access to me in the future for advice. I want to help others, as I've been helped over all these many years, and I really very much looking forward to it, July the 15th. We go live with everything. So we're getting very close to that date. So I hope people go to the website, pick something out for themselves, and see what they might be able to learn.

Dave Bullis 54:53

And I will also link to link to the your seminars in the show notes, you know, as well as any other. Site you have Steven, and it's just great too, because it's something that I've learned over the years. Whenever I want to take a seminar or a webinar or read a book or a filmmaking book, one thing I always my one sort of barrier to entry to reading it or buying it is the person has had to have some kind of experience. I think you've also seen it, Stephen, where you sort of see a book in the in maybe in a Barnes and Nobles, or on Amazon, and you see that they're, you know, the person that wrote it has never written a screenplay or never actually made it, made a film. And you say to yourself, well, what would they possibly know about something that they've never done? It's, a lot like me teaching you how to build a car and then saying, Well, I'm not a mechanic, nor have I ever designed one. I see you. You've actually, you've been there, you know, you've done that. You've done it many, many times over 30 years. And you know, and again, that's why I was blown away by having you on this podcast. Because you know, you've, you've done I mean, I'm gonna be honest with you, Steven half baked, I remember watching that movie on repeat over and over again, you know, growing up, because it was just absolutely hilarious. I mean, you've been able to sort of go in and out of, you know, comedy with half baked in Scary Movie two into Monster, which is more of a of a, not only as a drama, but it's also a personal introspective of the of these two women. Who are, you know, who are, you know, literal and figurative monsters, and then, you know, you now, you're doing your own projects, so it's always good to learn from somebody who's actually has gone out there and done it.

Steven Bernstein 56:33

Well, thank you. And I have done a lot of different things. I'm a producer now, a director, a writer, cinematographer. It's not to always been easy, but it's interesting. When you get to farther down the road, you realize how each of these things informs the other. I'm a better producer because I was a cinematographer. I'm a better director because I'm a writer and a cinematographer. And it's not just the films that have been made. I guess, in the last 18 months, I've been commissioned to write five other major feature films. It's been a very, very busy period for us. We have a TV series that's an advanced stage of development. And the reason I am now writing so quickly and so efficiently is that I'm borrowing from my other experiences as a producer, as a cinematographer, as a director, and I realize what I need to write and what I don't I understand what will work best and what works most efficiently, and it's a help. So look, if I can help others understand all these things based on my experience, I'm more than happy to impart it to them.

Dave Bullis 57:41

And you know, Steven, I know we're just about out of time. I want to again, say thank you so much for coming on and imparting your wisdom here for the past hour. And just in closing, where can people find you out online? You have any other social media links, and also you may, and just to give that seminar link again,

Steven Bernstein 57:57

Well, it's the key one to go to, and this links to pretty much everything to do with me is somebodystudios.com you can also find me, Steven Bernstein, writer, director online, and there's usually links to our courses or what's going on in my life there. Steve Bernstein, director, writer on Instagram as well. And of course, I say somebodystudios.com is pretty much available on all social media platforms, so we really hope that people might join us. Thanks

Dave Bullis 58:30

And everyone I will link to that in our show notes on the Dave bulls podcast. It's at davebullis.com Twitter, you can find me at dave_bullis. Steven Bernstein, I want to say thank you so much for coming on, sir.

Steven Bernstein 58:43

My very great pleasure. Was a great talk. Thank you so much.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.