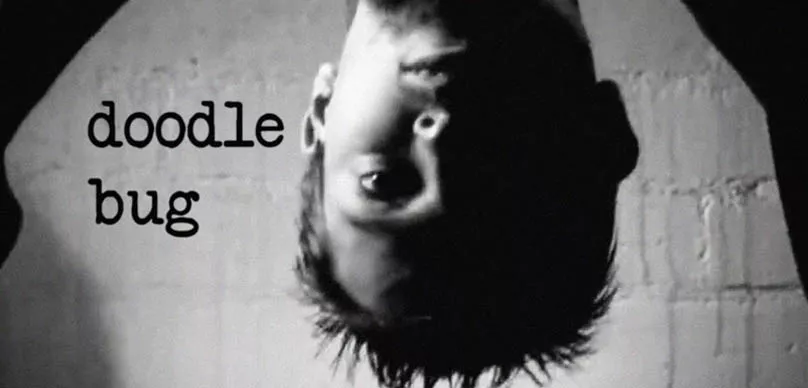

Director Quentin Tarantino made waves in international pop culture with his 1992 debut, RESEROVOIR DOGS. Suddenly, his explosive, unpredictable style was the one to emulate, and he found himself besieged by Hollywood power players who wanted his grubby little paws all over their high-profile projects. Proving himself as a true artist, Tarantino rejected the opportunity to turn himself into a big-budget tentpole director and instead retreated to Amsterdam to work on the script for his follow-up. The result was 1994’s PULP FICTION, and if Reservoir Dogs made waves, then PULP FICTION was a tsunami.

You can read all of Quentin Tarantino’s Screenplays here.

PULP FICTION, generally regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, is inarguably a zeitgeist film. Not only is it one of the definitive 90’s films, the film itself played a significant role in defining the 90’s. It influenced trends in fashion, music, art, film…the list goes on. It remains most of the quotable films ever produced, and continues to have a huge impact on contemporary films. PULP FICTION is a once-in-a-lifetime cinematic event, a work that shakes the language of film so fundamentally to its core that the medium never truly recovers.

I was a senior in high school when I first saw PULP FICTION. I had heard about it all my life, and had that iconic teaser poster with Uma Thurman lying on a bed seared into my brain by virtue of a decade’s worth of pop culture exposure. Watching PULP FICTION was a visceral experience for me, one that I count as highly influential within my own development as a filmmaker.

Most of us have seen PULP FICTION. It is simply one of those films that, if you don’t seek it out yourself, is forced upon you by well-meaning friends. So much has been written about the film that I won’t go into the specifics of the labyrinthine plot. Chances are that I could show you a picture of a guy in a black suit, white shirt and sunglasses, and you’d instantly think “Tarantino”. His stories and creations have entered the realm of archetype, becoming instantly recognizable across linguistic and cultural barriers.

In terms of the cast, PULP FICTION will always be remembered as the film that (briefly) resurrected John Travolta’s career. He had been one of Tarantino’s favorite performers and was plucked from actor jail to headline the film as long-haired hitman Vincent Vega. While its arguable that Travolta has since squandered the goodwill he earned from this film, it’s hard to deny that he’s never been better than he is here.

Samuel L. Jackson also received a considerable career boost as Vincent’s jheri-curled partner, Jules Winnenfield. His wild-eyed performance results in a collection of some of the most memorable one-liners in cinematic history (“English motherfucker, do you speak it! Say what again, I dare you! This is a tasty burger!”). I’m not sure if Jackson himself has ever topped this performance, which quickly followed after his turn as “Hold On To Yo’ Butts” in Steven Spielberg’s massively successful JURASSIC PARK (1993).

The inclusion of Bruce Willis to the cast is heavily significant to Tarantino’s development as a filmmaker. For a guy who was on the outside for so long, who lived and breathed movies as if they were air, the signing of Willis to the cast must have felt like a monumental event. Willis gamely leaps out of his comfort zone for Tarantino, resulting in one of his greatest performances as Butch, a gruff boxer whose dignity refuses to let him throw a fight for money.

Tarantino fills out the remainder of his supporting cast with faces both new and old. Returning to the Tarantino fold are Tim Roth as Pumpkin—a manic bloke and professional robber—and Harvey Keitel as The Wolf—an urbane, sophisticated “fixer” for Marcellus Wallace (Ving Rhames). Despite being the leads in RESERVOIR DOGS, here they are relegated to minor (albeit memorable) roles.

Amanda Plummer plays Honey Bonny, Pumpkin’s unstable wife and fellow partner-in-crime. As Marcellus Wallace, Rhames gives one of his most iconic performances, completely nailing the imposing, brutish nature required of him. Eric Stoltz and Rosanna Arquette steal their scenes as husband-and-wife heroin dealers Lance and Jody. Christopher Walken appears in a cameo as the preternaturally creepy Captain Kuntz, who visits a pre-teen Butch to explain the significance of a watch that belonged to Butch’s father.

And then there’s Uma Thurman, who is usually featured prominently in advertising for the film (see the aforementioned one-sheet poster). Her unforgettable turn as Marcellus Wallace’s femme fatale, cokehead wife turned her into a star overnight. Tarantino has often gone on record declaring that Thurman is his “muse”, the one talent that inspires him more than any other. Their collaboration for the KILL BILL films began during production of PULP FICTION, when Tarantino and Thurman would hash out the Bride’s story during breaks in filming. Indeed, Mia Wallace’s story about her work on the fictional “Fox Force 5” pilot reads like a rough draft of the character dynamics of The Viper Squad in KILL BILL. It’s easy to speculate that their relationship was/is romantic in nature, as most director/muse relationships are, but I’m not exactly here to talk about the man’s sex life.

With the financial backing of Miramax producers Harvey and Bob Weinstein (as well as a continuing collaboration with RESERVOIR DOGS producer Lawrence Bender), PULP FICTION jumps leagues beyond Tarantino’s debut in terms of visual presentation. Retaining the services of cinematographer Andrzej Sekula, Tarantino opts to shoot on 35mm film in the anamorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio. This makes for bold, frequently-wide compositions that highlight the characters amidst the dried-out San Fernando Valley landscape. Tarantino and Sekula cultivate a color palette that’s reminiscent of aged Technicolor—creamy highlights, slightly washed out primaries and slightly-muddled contrast. The result is a burnt-out rockabilly aesthetic that jives with Tarantino’s Elvis-inspired, anachronistic visual style.

For PULP FICTION, Tarantino also brings back his RESERVOIR DOGS production designer, David Wasco. Wasco does an incredible job of applying Tarantino’s signature sense of “movie-ness” to a realistic world. Everything is believable, yet just a little larger than life. One of the film’s biggest set-pieces is the Jack Rabbit Slim’s set, which was built from scratch to evoke kitschy Americana diners that were popular in midcentury Los Angeles. The restaurant reads as a geek shrine to Tarantino’s love of cinema, with posters adorning the walls, pop culture relics scattered left and right, and waitstaff dressed up as famous Old Hollywood icons (look out for RESERVOIR DOGS’ Steve Buscemi in an unrecognizable cameo as “Buddy Holly”).

The increased budget also means new toys for Tarantino to play with, and where RESERVOIR DOGS was compact and minimalist like a stage play, here he goes all-out with a dynamic camera that bobs and weaves as it follows its subjects. A Steadicam provides ample opportunity for Tarantino to explore his enthusiasm for long tracking shots. Watching the film recently, I became acutely aware of how subtly complicated Tarantino’s tracking shots are. There’s one in particular about three quarters through the movie, where the camera follows Willis’ character as he stalks through a vacant lot and squeezes through a chain-link fence. The camera doesn’t break stride as it glides through the hole after him. The hole was barely big enough for Willis to slip through, so it blows my mind how someone wielding a cumbersome Steadicam rig could effortlessly slide through the same opening without getting caught up in it. This shot in particular has stuck in my mind, and I still can’t figure out how they did it. Tarantino’s mastery of camera movements is matched only by the sheer audacity with which he employs them.

The infamous “trunk shot”, one of Tarantino’s most well-known signatures, is employed here as well. It had previously turned up in RESERVOIR DOGS as well, but PULP FICTION was where Tarantino’s style became really established and the awareness of the trunk POV shot was first recognized.

One of the film’s more-subtle techniques, however, was the employment of rear projection during several driving sequences. Rear projection is an old filmmaking technique from the days before green screen that would project travelling road footage behind actors to simulate motion (i.e., driving). More-realistic compositing capabilities were very much available during the production of PULP FICTION, but Tarantino’s employment of the outdated technology was an inspired melding with his vintage aesthetic. What’s so brilliantly subtle about it is that the rear projection itself is in black and white, while the actors are rendered in full color. The effect is so understated that it’s easy to miss it, but adds a sophisticated, vintage flair to the film’s look.

Of course, no discussion of PULP FICTION would be complete without mentioning its groundbreaking use of music. A sourced soundtrack comprised of prerecorded music hasn’t been this revolutionary since Martin Scorsese made the practice en vogue with his debut film, WHO’S THAT KNOCKING ON MY DOOR? (1967). Instead of hiring a professional music supervisor, Tarantino assembled his eclectic mix from his own record collection, oftentimes sourcing it from the vinyl itself—hiss, cracks, and all. This creates a warm, vintage sound that perfectly complements the use of various soul, pop, and surf rock tracks. In particular, Dick Dale’s “Miserlou” was rescued from relative obscurity to become one of the most iconic pieces of music of all time, all because PULP FICTION decided to use it as its de facto theme song. It’s very rare that a piece of music becomes so indelibly tied to its appearance in a film, but Tarantino manages to do this regularly. It’s become so much of a calling card that his fans eagerly await the soundtrack listings of every upcoming project to see what musical treasures he’ll dig up.

There are numerous storytelling conceits that make up Tarantino’s directorial style. The razor-sharp wit. The creative use of profanity. Self-invented product brands like Red Apple Cigarettes and Kahuna Bruger as part of a fabricated sandbox reality his character inhabit. But it is also his structural quirks that reveal a lot about him as an artist. Most Tarantino films begin with lengthy, simple opening credits of text over black. To me, this reads like a reverential nod to formalistic influences from classic cinema; a humble genuflection at the altar of The Church of Film before he delivers a fiery sermon. His tendency to construct his films in a nonlinear timeline reflect the way his mind works—those who have watched an interview with him can attest that he’s all over the place mentally, hopping around from point to point at a dizzying speed, overlapping, pre-lapping forward-lapping while still somehow making sense. The use of book-like intertitles and chapter designations to divide up his narratives come from the pulp inspirations behind his stories and the lack of a formal education in traditional three-act writing structure. Placing himself in a small cameo/supporting role speaks to both a mild narcissism on Tarantino’s part, but forgivable given how damn earnest he is about his work. The lingering shots on feet, well…. that’s fairly obvious why he does that.

Together with his longtime editor, the late Sally Menke, Tarantino has made a motif of the Mexican Standoff. Even when it’s not explicitly included in his films, as it is in RESERVOIR DOGS, he incorporates its compelling aspects seamlessly into the narrative structure. He uses incredibly long, drawn-out dialogue sequences to sustain suspense almost to a breaking point, and when violence finally erupts, it is quick, shocking, and efficient. The magnitude of the carnage is amplified by the sustained build-up, a fact that Tarantino and Menke know all too well. This dynamic is included in some form in virtually all of Tarantino’s film, with INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS (2009) seemingly made up entirely of Mexican Standoff-like sequences.

To prepare for writing this entry, I watched all of the supplemental features for PULP FICTION, including Tarantino’s appearance on the Charlie Rose Show in 1994. I mention this because Tarantino regularly does something akin to The Directors Series himself, in which he watches a given director’s body of work in chronological order to determine the course of their career and the evolution of their style. I was blown away to see the reasoning behind my efforts validated by a successful major filmmaker. A filmmaker like Tarantino knows that it’s absolutely essential, if you’re going to make film, to watch and study the broad spectrum of film works. One would be shocked to find that many aspiring filmmakers aren’t versed at all in the century-long history of the medium. I forget who made this point (it might have been Charlie Rose or Siskel & Ebert), but there was an observation that those who tried to mimic Tarantino’s style as their own would cite him as a major influence, yet they showed an ignorance to the directors that inspired Tarantino himself. They had no interest in familiarizing themselves with Howard Hawks, Brian DePalma, or Mario Bava, all of whom left an indelible mark on Tarantino’s artistic formation. A limited sphere of influence is a major hindrance to true creativity.

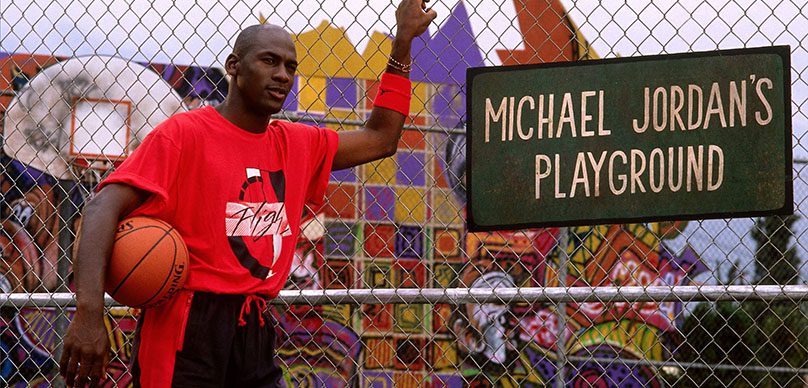

I don’t need to elaborate on the windfall that the release of PULP FICTION bestowed on those behind its production. It was a major box office success, it won Tarantino his first Academy Award, and it won him one of the most prestigious prizes in all of cinema: the Cannes Palm d’Or. It single-handedly enabled the Weinstein Brothers to become the producing and award-lobbying powerhouses that they are today. Audiences responded to it in a manner as violent as its content, with patrons suffering heart attacks in the theatre or laughing so hard their chairs broke. By rousing the moviegoing audience from its unknowing complacency, Tarantino had become the hottest filmmaker in the world, and one of the leading cultural tastemakers of the 1990’s. And most importantly, he had done it entirely on his own terms. The cinema would never be the same.

Sponsored by: Special.tv – Stream Independent