Today on the show we have filmmaker Ryan Templeton. Ryan has been developing a “Frankenstein” self-distribution model for the ever-changing filmmaking landscape. Though this interview was recorded before the pandemic it seemed almost Nostradamus-like in its tone.

Ryan and I discuss the changing Hollywood landscape and how indie filmmakers can take advantage of new opportunities that are being created in the vacuum left by the studio model of doing business.

Enjoy my conversation with Ryan Templeton.

Right-click here to download the MP3

Alex Ferrari 0:00

I'd like to welcome to the show Ryan Templeton man, thank you for coming on the show, brother.

Ryan Templeton 0:14

Yeah, man, great to be here.

Alex Ferrari 0:16

We're here to talk about distribution and how to make some money with film in the film business, and your unique approach to it. So we're gonna get into the weeds here, everybody. But before we get started, how did you get into the business? Because I, I heard through the grapevine High School, the musical or something. So please explain yourself, sir.

Ryan Templeton 0:36

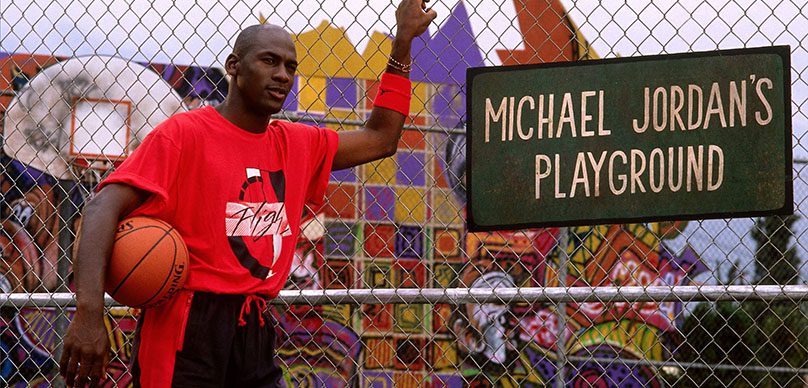

Yeah, so I so I started actually at the gateway drug, right, the gateway drug which is acting, that acting bug bit me and I mutated into a carnival freak. And, you know, I started getting a break where I just fell down this, this well, where I just love this business. And I had an opportunity to be in High School Musical. And I did, the best thing to come out of that was that it became a South Park character that when they made fun of when they made fun of High School Musical, they have my character. It basically turned into a South Park character. It was actually yeah, it's that's probably the the highlight of my entire life.

Alex Ferrari 1:16

You, you've arrived, Sir, I don't even know why you're speaking to me so

Ryan Templeton 1:21

Well, you know, the reality is behind it is that once you kind of get into it, and you start to like, see the all the back end side of things like so once you get on the set, you realize kind of how small the actor is, you are the face of the franchise, but at the end of the day, like there's tons of things that are happening kind of all around you and what kinds of things that are happening before you even get there. And after you get there. And so, for me, I just found that I was just fascinated with this whole process. And I really wanted to understand the whole thing holistically. So I started writing, about the time actually that I was in high school musical, which was years and years ago, I don't even remember 15 or more years ago, probably 17 years ago, actually. So I started writing and creating scripts and things for myself, started doing short films, started producing those things started acting in them. And I knew how to edit. So I started doing the post production piece as well. So that's kind of what I ended up. Getting into how I kind of got into this game.

Alex Ferrari 2:28

Yes. So and you you reached out to me, a friend of our Rob Hardy actually reached out to me said, Hey, I had this great conversation with this filmmaker about this new business model, that I think you really should talk to him. So we spoke and I wanted to hear I want you to explain to the tribe, what is this new distribution business models that that's making money or can potentially up filmmakers make money?

Ryan Templeton 2:55

Well, it's not necessarily a new distribution model. It's a Frankenstein of kind of the traditional the traditional business model and the business model that we're now in. So I think it's probably best to talk about maybe let's just go to the traditional business model is getting blown up and you've got an episode about that, which I would encourage people to go and check out. But essentially, the the theatrical exhibition is, is basically going away for the major studios, that is not part of their their business calculus anymore. And so, look at Disney, for example, Disney owns 47% of the market share, but they're only going to create 17 films. So that is not enough to cover all those weekends. And that's only one segment of an audience. And so, you know, the president of AMC, Adam, Aaron basically says like, we need more movies, right? These major studios are in a 16 week or 17 a week, you know, weekends a year. And, but that's not servicing, what is our theatrical exhibition. And so we see reboots, remakes, sequels, tentpole franchises, all this, you know, regurgitation of old IP, because that's the easiest thing to market. But what we're realizing is that, that audiences aren't engaging with those things because the as we become more and more digital, right, you and I are talking right now like not in the same room. And and that's amazing, but what we're actually finding and I this is my background is in marketing is that we want human connection. And so that's what people are engaging with, if you look at online, the influencers, right? We want to connect with human beings and our theatrical spaces is actually a good place to do that to be shoulder to shoulder with somebody enjoying the same thing because when you hear them laugh, right, that gives you you know, that serotonin that makes you feel good and feel like you're part of a community and that's what we need. But those big businesses can't compete in that space because they're not human. They're not human. There's though, who's the face of Warner? are just nice, apparently. You know, Disney, exactly. I mean, it was Walt, but back in the like, but we don't have that face anymore. And this is, you know, and so people want that thing. And so this is why we engage with actors and celebrities, because that's what draws us to things, right? So we recognize that that person as a vehicle of empathy, it's the the protagonist, or the antagonist, or what whoever it is, that is in this film that you, you, you relate to, that's who you travel through the journey of the film with. And as you see, and recognize those people more and more frequently, even though you don't necessarily know that, like, I, again, I'm sitting here chatting with you, I listened to your podcast, and I think you're doing you do great work, right. But I feel like I know you. But this is only that, you know, the second or third time that we've ever chatted. And so you you are a vehicle for me, that that I imbue you with a certain familiarity. And so it's the same thing with our films, the that's why you go out and you get, you know, talent that people recognize it doesn't have to be a list, you just have to recognize the talent because that's how you bring the people in, it's this is my trusted vehicle for how I get into the film. And so independent filmmakers then have a huge opportunity in front of them with the theatrical space, because the the, the major studios are pivoting a huge amount of their resources away from the theatrical space into streaming. And with that, they're gonna now have to start creating crazy amounts of content, almost unsustainable amounts of content. And you look at Netflix, I think is somewhere 1,000,000,015. And then they added to 2 billion just recently. And you can expect that basically everyone is going to follow suit to some capacity, I think Apple is at 8 billion. I heard peacock is somewhere in that 7 billion, you know, Paramount network, and HBO, Max and all these content providers, have, they have this giant catalogue, that's going to get people to start the subscription. But the only way to keep people is new content. And so their business calculus inside that is going to be two things. Does it bring me new subscribers? And does it retain the subscribers that I have? That's it. That's all those business models are going to care about. So and you see this with Netflix, as they dial up the spend on their original series. They dropped a lot more stand up comedy specials and kind of, you know, mid tier documentaries and things like that things that are low cost for them so that they can always have something new.

Alex Ferrari 7:52

Every week, there's a new standard. This is you.

Ryan Templeton 7:55

I mean, man, you how much content do you put out just to maintain the audience you have now? I'm not even kidding. Like, now scale that?

Alex Ferrari 8:03

No, yeah, I don't my spend was 8 billion last year. I'm thinking about a 10 billion on my content, but I'm Miko, just nine I'm not sure yet. But I know that a bit. To be honest, on a business standpoint, one of the reasons why I've been able to really penetrate the audience that I'm going after, which are filmmakers, screenwriters, content creators, is because of the massive amount of content that I put out and the massive amount of energy that I put out on a weekly basis that nobody else has really tried to do or figured out how to do the same way I do it or with the way I do it. And it's that the same model works with what this what the studios in the streaming services are doing. I'm just doing it for less than a billion dollars.

Ryan Templeton 8:43

Well, we don't need you shouldn't also discount the fact that you are doing this genuinely right, like correct. So you are you are the face of your franchise, indie film, hustle is not anything other than basically Alex Ferrari.

Alex Ferrari 8:57

It'd be, it'd be hard to sell indie film hustle without me. So like, if a company came in, like, you could sell Disney, you know, you could sell Apple, I mean, on who'd buy? But you know, who could afford it. You know, you could sell Netflix, but that, but I'm glad that I'm putting into film hustle in that category. So I appreciate you. I appreciate that. But no, it's very difficult to sell this this business without me attached to because I am the face of the business. And that's what makes the business run. And there's many, you know, many companies that do that. And I know like there was a couple other other brands within our niche that tried doing that. But when they lost the main guy and YouTube shows happen all the time where the YouTube show host changes and everything drops. Yes, there's attach that person

Ryan Templeton 9:42

Well, and this kind of goes into exactly what you always talk about, right? Like you talk about the niche, right? Well, the niche is the people who look at Alex Ferrari and go, this is the dude like, this is the guy right? This is the guy whose material that I want to see. And so filmmakers do need to focus on the niche but what niche people Want is actually to then project the thing that they think is niche into a wider space. Right. So a good example, which I try not to use, but like Napoleon Dynamite, right, Napoleon Dynamite, and they use this film all the time to be like, Look, Napoleon Dynamite was maybe

Alex Ferrari 10:20

It's an outlier. It's an outlier. But but the principles are solid.

Ryan Templeton 10:24

The principle behind it is solid, right? Because what is the point of Napoleon Dynamite. It's about a small town in Idaho. And so that's a very niche content. But what that content did is it created a funny affectation of basically like, who these people are. And guess what, those are the people that grabbed on to it, and said, this thing is hysterical. This is about us. And they projected that out into the world. And I mean, everywhere in the world.

Alex Ferrari 10:52

It's same thing with Big Fat Greek Wedding. I mean, I mean, that was another one that was just like, oh, it's about a Greek family, like, no, it's about every family, and then everybody grabbed on to it. And then it exploded to what it became. It's all it's all relative, you know, I actually use napoleon dynamite in my new book, The Rise of the entrepreneur as a model. And I even say like, this is an outlier. But the principles of what happened here are sound, as opposed to Blair Witch Project, or paranormal activity, which were complete lottery tickets, and cannot be replicated. But the concepts behind a Napoleon Dynamite or Big Fat Greek Wedding can be replicated if you use the base concepts correctly. And there has to be a little bit of lightning strike to make that work as well.

Ryan Templeton 11:36

Yeah, but any successful, any successful property has some sort of lightning strike to an extent, right. And that's why because it's such a risky business, like, you look at best practices when it comes to best practices of the business. So just because we're independent doesn't mean that we should not look at what the industry does. That's best practices. And if you look at just the traditional model, what they're doing is they're diversifying their risk across multiple properties. So it's are you familiar with slated? I am sir. Okay, so slate, it has like this rubric, where they basically are talking about independent films and theatrically released independent films, they do a study from, can't remember the dates, I think it's 2012 to 17, or 18, or something like that. But basically, what the they show is that the number of winners and losers at the box office are about equal to about 50%, which shouldn't be terribly surprising, because those are businesses that have actually gotten to their point of sale, which is the theatrical space. And the losers make back, you know, on average, you know, about a point, two, five ROI, but the winners are making back like a 3.35 ROI. So if you put those things together, right, the the overall is a 2.41. ROI.

Alex Ferrari 13:00

And for everybody return on investment, so everybody knows what ROI is

Ryan Templeton 13:03

Yeah, right. Yeah. Yeah, and that's, and so the 2.4 is a decent return. Now, people who invest, they want like the forex and they want the 10x, and they want these giant returns. But a 4x can happen if you have just one of those kind of, let's say you made four films. One of them's a winner, one of them's a loser, one of them is where one of them is a loser. And the rubric basically, is that you would get 2.41 return on investment. That's what sleds data tells us. But investors want that for X number. So you would really need to hit a homerun in one of these things in order to hit that four, or even a 10x. And those are unicorns, right. So if you want make money in the film industry, then you just have to make lots and lots and lots of films. And that's what, that's what everyone says, right? You just have to make lots lots of films. The problem is, is if you don't make a great first film, it's really hard to get your second and it's really even harder to get your third, especially if these two didn't do well. And so what happens is our artists get one chance. And so we put all this pressure on these artists to make a film that's going to give them a career. And that's not fair. Especially for first time filmmaker, that's not fair. Like my first film. Yeah, I would hate to have that be the only thing that people ever judged me on and, and the same sorts of the same sort of pressures put on everyone. And then once you have that first one, how do you get the second one because now you want to try and scale up? You want to try and keep moving the ball forward. And so what we ought to be doing as independent filmmakers, and this is the business model is creating a career play the long game. So get four filmmakers that each have their own story to tell and You work together. But you have to work within the model that exists. So how do we value what a film is? Now we're talking value, what's the value of a film? Well, we know the value of the film based on the budget, because we always talk about the budget of this film is X amount. Budget and cost are not the same thing. It's not the same at all, my budget could be $12 million, but I only ever spend $3 million. So that so that's the value is 12, the spend is only three and how do you calculate the value. So you calculate the value by taking the script and going through it the way that a line producer does. So this is what all the studios do. They go through and they say it cost me X amount of money based on the DGA rules, the WGI rules, sag AFTRA, IRC, and they go through the whole thing, like I absolutely need X amount of things for this film, these are the hard costs and then they make phone calls. And they basically get the bids for what these things cost. And then when the film is actually made, they put those real costs to the film, at the end of the day, and then they know exactly what that film budget is. But it doesn't necessarily mean what was spent, they'll spend on the things that are hard costs, right? They'll spend on you know, renting the equipment, they'll spend on talent, Visscher, the talent and they'll spend on those things they absolutely have to have, but they already have an infrastructure. A lot of these major cities have an infrastructure, so they're portioning. It's an apportionment of their actual people that are inside that is creating this thing called soft money. And soft money isn't like a tangible hard asset. It is Alex Ferrari is working for Warner Brothers at $100,000 a year. But on this film, he is the writer and the director. So you get the DGA minimum, and he gets a right, and he gets a game. And both of those are going to be a combined are going to be somewhere in that, you know, 160,000 or whatever. So because I only pay you 100k A year is my employee, I've created 60k in soft money.

Alex Ferrari 17:18

Okay,

Ryan Templeton 17:19

See, so so you can do this same sort of thing at the independent level. And at the independent level, essentially, it's the same thing. I go through the script, I find the value of the script, if the value of the script is $2 million, which is still a low budget film, this is, you know, and people go $2 million. Yeah, if you're spending $2 million, yeah, you should throw your hands up there and be like, That's ridiculous. But independent filmmakers don't spend the $2 million, they spent a fraction of that because the $2 million value on the film, and you play within the rules of the guilt, because at the end of the day, you want to sell this film, you want to take it to theaters, you want it to live on a streaming service, all those major players play nice with the artist skills. And the reason they do that is because that is the bread and butter of their business. Without the artists, they don't have films. And so it that's what we have to start to talk about is that you play nice inside this budget, but you can dangle the rules to work in your favor. And you do that by creating soft money.

Alex Ferrari 18:23

So I'm confused in regards to the valuation of the of the product. So if you're if you're making a movie for 100,000, and your value yet is 2 million, I still haven't heard the way to do that.

Ryan Templeton 18:34

So all of the positions have to be filled, right. So everything that that is on a film has to be filled. But if I give you a position in writing that you can do that in pre production, and you're my writer, and then I bring you in as my director, and then you are covering two positions, I only pay you for one thing, right? So you get four kind of predator filmmakers together. And you run basically these, you know,

Alex Ferrari 18:59

So you're getting more. So basically the bottom, the model you're talking about is you're creating a bigger bang for your buck. So someone like myself, who can come in, right direct produce, edit, DP bring in their own camera gear, I'm bringing a tremendous amount of value to the project that doesn't install money yet, which is all soft money. So basically, when I made my film on the corner of ego desire, when I made it for about $3,000, hard costs, the value that I presented was probably anywhere between 50 to $100,000. Purely because of all the stuff that I was able to do. As if as if as someone coming into that thing, that's great, but I'm not sure how that how Okay, so continue with your process because you asked me to poke holes so I'm going to poke holes if I see something

Ryan Templeton 19:44

Absolutely. So the the point is like if I get let's say I get for Alex Ferrari, so I get my coning.

Alex Ferrari 19:51

That's impossible. That's impossible. That's impossible, sir. There's only one of me. Obviously,

Ryan Templeton 19:55

There is only one of you. We'll get we'll get some.

Alex Ferrari 19:57

If there was if there was four of me I would rule A world. Let's just put that straight up.

Ryan Templeton 20:03

Okay, so we'll get one of you and then we'll get kind of the second tier Alex Ferrari is it

Alex Ferrari 20:08

Their just copies sir copies of their copies of every copy becomes less and less hustle, because it just degrades by the copy. It's kind of like that old, low to that old movie with Michael Keaton. Multiplicity.

Ryan Templeton 20:17

Multiplicity. Yeah. So we multiplicity, Alex Ferrari here, and then. So we got four of you, right. So now think about all the positions you're going to cover, right, you're going to write, you're going to direct, you're going to shoot, you're going to produce, you're going to make the light all your edit, you're going to do color, you're going to do all your di t, you're going to do your data management, you're going to do everything I need to do your sound design. Well, now, I only have to pay for employees to get all those things, how much did all those other things cost? Now, I'm going to ask you, you for to do that for two years and make me four films, each of you get to run the helm at four films, you do it over the course of two years, now I'm going to pay you your minimum, I'm going to pay you and Alex to and Alex three and Alex for the minimum amount of money you need to survive. And what's going to happen is you're going to see that the difference between what you should have made if you were writing, directing, producing and doing all these things through the unions, what you should have made that giant gap is going to create a huge amount of soft money. That is what you own as, as the filmmaker, right. That's your basically your deferment. And so what you do is then you actually get the hard money to pay you and Alex to and Alex and Alex for you get that hard money for your minimum basic living those that money from an investor, and you pay that money back first. So if you're let's say your minimum amount you have absolutely have to have is $50,000. Now I'm making a movie that might cost me, you know, $2 million. On paper, I have these four people who are creating this huge amount of saving, so maybe a million dollars in savings. So I basically have you guys all for $200,000, I'm saving a million dollars. Now I only need $800,000 In order to make four movies. Because you're going to work for you're going to work for two years on that on that salary, essentially. And that's

Alex Ferrari 22:20

Okay, so you're basically creating a slate of films and basically you're hiring everybody salary to create these these forms of to create these products. So it'd be it's, it's it's simple economics, basically. So as opposed to hiring our freelancers to build your and I always use this olive oil business. So if you if you hire out freelancers to build the bottles, bottle that models do all this and that. So like when I had my, when I had my olive oil company, which again, if no one has heard of this, that's a whole other story for a whole other day. But when I had my olive oil gourmet shop, I had staff, I, you know, I paid them a salary, they sat there and they bottled olive oil by hand in my my factory, which was my my store. So by doing that I was able to create based on paying them an hourly rate, how many bottles could I fill? How much product could I create, based on the hourly now if I would have paid them per bottle, or per groups of bottle as a freelancer, the value wouldn't have made sense. This is right. This is basic economics for any business when you hire a salary versus a freelancer or contract worker, but you're trying to create that model within a cinematic slate of films

Ryan Templeton 23:32

Exactly. And within the independent scene because correct, we talk about independent and part of the problem is that we branded ourselves as independent. So that literally means by yourself. We really, really

Alex Ferrari 23:43

Independent should be independent of the studio system, independent of the system, not independent, like I'm all by myself, somebody had

Ryan Templeton 23:49

But we but we branded ourselves that way, right? By being Renegade and kind of being like solo entrepreneurs and this sort of like look, look at me run around with all my gear all over my body.

Alex Ferrari 23:59

I don't know what you're talking about. I've never done anything at all ever.

Ryan Templeton 24:03

Yeah, there's I'm sure there's some behind the scenes.

Alex Ferrari 24:06

There's a picture of me on this is Meg with like this huge rig with a camera and the mic hanging. I mean, literally, if I had a broom up my butt just like I start cleaning the floors while I shot it was insane.

Ryan Templeton 24:17

Well, that's but that's the whole point. Right? And so as you have this, this independent kind of branding that we give ourselves that we feel like we have to work alone, but we don't in fact, it's actually so much better to work with multiple people because if you put everybody in an equity position, so like I work in post production, you you worked in post production and you know that post production is a service based industry correct. So they come to me and they hand me a film and they hand me money to work on the film and I edit in the you know, we do the assembly or we do whatever we do in the the online, the color, whatever it is that we do the effects. I get paid for that service. I owe nothing when it comes to that film. But the only way to actually scale up your business is to own a piece of equity. And that's, and so what happens is then if you take the the savings that you had in yourself money, that becomes your equity investment in your film. And so when I turn around and I go out, and I raised this at, you know, $100 million, or whatever it is, I then can turn around with that same group of filmmakers and make a very, very strong claim that 50% of this movie actually is mine because of just the equity play.

Alex Ferrari 25:31

Right. And the one thing I've always said multiple times in the shows that if someone showed up with half a million dollars from me, I wouldn't make 10 to 12 movies. With that half a million dollars, I would not try to make one movie, I want it because making a movie is like pulling up pulling a slot machine. So I would rather have 12 shots as opposed to one shot to

Ryan Templeton 25:49

Yeah, sit down and play some hands of poker, right? If we're gonna play this clip, let's not pull the slot machine. Let's play the game. Let's learn the rules. Correct. And let's have a strategy. Shocking. Yeah. Amazing. And, and then, and then place your bets accordingly, right. So if you know that you got one that's a little bit soft in in the slate of films, that's fine. Just do that one as best as you can recoup as much as you can, it can't be zero. But then do the next one. And then maybe you're going to want to gamble a little bit more on that one. And so what you have to do with these films that say, again, I'm using four because it shows you know, you failed, yeah, you can do four films in two years. And you can tolerate any people for two years at a time.

Alex Ferrari 26:35

I've met some people in the business, I'm gonna say I'm gonna call shenanigans on that one. No, you cannot. But you can pick them, you get to handpick them. And if someone has to go, they have to go and you hire and you play somebody else in there. And it's just part of, it's just part of what you're creating. So you're basically just creating a production company that has a slate of films where you're hiring crew, you know, that can do multiple jobs. So like, you know, if you hire a DP, it's a DP will own their own camera, their own lenses, their own grip truck, maybe you and you pay them a salary position where they're getting general, they're getting a steady income guaranteed every day, you know, for months at a time, and something that's going to make sense for them. And or some sort of equity in the project that they're creating, and kind of making it more of a communal way of making films on the making side of it actually producing the product is that basically what you're telling me?

Ryan Templeton 27:29

Basically, yeah, and so because that person, you know, that DP would get hired on maybe one film a year or one every couple of years things? You know, that's it, you know, what I'm doing is, I'm guaranteeing that you will work on at least two films for the next two years. So I'm guaranteeing that that salary. And so then what I'm doing is basically saying your value is based on the DGA, the Directors Guild of America, what you should make working on this, what's the least amount you're willing to take everything that you create in soft money becomes your piece of the equity in the overall budget,

Alex Ferrari 28:06

Which now, so I understand what you're saying. So it's, again, the basics is you're just creating more value by leveraging time and amount of films, and you dialing down was found as well correct. And you're dropping the budgets. Because of that, you're just, you're just being smarter with your money, which sounds great. And I agree with it, I agree with the concept. So the concept of actually, production of the film. Makes sense. And it's something that I've done many times in the past, I haven't done a slate of them, per se I've done it one offs. But if you you know if i People always ask like Alex, why don't you make like five or six movies a year at your budget range, which is gonna be under $10,000? I'm like I could if I want to, but I don't I'm busy doing other things right now. But I could easily do that without question because I have the infrastructure to do it. I have crew that could do it with and your model, I could easily bring two crew members that I work with, and they would be on board without without question. But the question I have for you then is the production is great. And you're able to make your movies at a much more affordable rate. What is the business model to recoup? What is the distribution model? And how can you generate revenue from these films?

Ryan Templeton 29:16

Okay, so yeah, that's great. So essentially, what you're doing is you're going to do kind of a, your day in day is going to look a little bit and I don't know how familiar your audience might be with day and date release. But that's basically you drop it into a theatrical space. And then you put it on a transactional Video on Demand, which means you're paying to either rent or buy that property. So your theatrical, you just go right to you can just go right to exhibitors, and say, I have a finished film. This is my feature film. This is what it looks like. This is Susan, this is the trailer, there's the chiar and they will say yeah, you know, let's do a 6040 or 5050 at the gate. And you show that there's actually like people in your community that one audience see honestly an Audience Yeah. And so that means you have to do that. The work ahead of time to get to that point, but essentially, you're distributing it either directly to the theatrical exhibitors yourself, or you just partner with a theatrical distributor who already exists in a space who does independent films. And there's tons of them that there's tons.

Alex Ferrari 30:16

Yeah, it's always gonna say this. And this is something that I think is one of the big kernels nuggets of gold that you're throwing out there is that there is I do truly believe that the theatrical experience is not a growth industry. For as a general statement, it is not where everyone's going. It is not where I mean tickets, I've either flattened or r&d r&d declined, the occasional big tentpole will maybe jump that number up. But people aren't going more to the theaters, they are watching more streaming content. They're also not renting or buying as much as they used to that that's a holdover from the video store days. And the as the new generations are growing concepts of renting and buying, of buying the movie is pretty awkward, because like, you could just go to Netflix or Hulu, or one of the many streaming services to watch. But the one thing I want to bring out here is that there is a big opportunity for independent filmmakers to fill the void that the studios are leaving behind in the theatrical space. As crazy as that sounds, if you use different models, like I talked about in my book, like the regional cinema model, or being able to bring in an audience, and you can target audiences, or if you go after a niche, and you can prove that and it's the I just released a podcast yesterday on film intrapreneur, which was about how the documentary awake, the life of Yogananda did gangbusters theatrically because they were able to target the audiences of followers of Yogananda in theatrical throughout the country and throughout the world. So there is a huge market there, do you have any advice on how to get into those Viet in those theaters, without, without a middle without a middleman to I would prefer not to go to the theatrical distributor

Ryan Templeton 32:01

This is and this is the thing is like so traditional, you needed to have like a sales agent, someone who's going to help you could roll the sales, right, but because you are your own brand for each of these movies, right, you are the filmmaker, so you are the brand. So what you should be doing with that is be building up the audience that you're going to carry with you into these theatrical spaces, which means, you know, building up that following either on social media platforms, or even a Patreon, a Patreon could actually be your TVOD that actually is realistic to have a Patreon actually be your look at and drop me a buck every month for five bucks every month. And I'll give you all access to everything that I do behind the scenes. And you create kind of like almost like a like a corridor crew. I love those guys put them, you know, kind of like but sure showing how the sausage gets made behind all these films. And then that becomes valuable to an audience who wants to learn about filmmaking, and how this thing was done all the way from start to finish. So that's how you can own your TVOD. Now, if you go to a theatrical space, you can do targeted analytics for a specific theater. There's a company called comScore. If you're, if you're familiar with them, and you can literally go based on look this, this exists right here. And all the films all the comparable films that I have, my films are like this have performed really well in this area. So that means that my demographic is in that area. So now what do I do? I pump money within, you know, maybe 1015 miles, I'm not sure what the exact mobilization rate is around this specific theater, but you start pumping your marketing dollars into that actual radius demographic for those people. And you try and drive them to that one point of sale. And that one point of sale, whether it's successful or not, it doesn't matter, because theatrical is just about marketing. It's just about amplifying the voice that you have. So as soon as my film goes to the theaters, I now have that much more street cred. Right. And now, I am a poster that someone walked by as they went up to the go and see whatever Disney was showing, they saw my poster in there. And then when they see my poster, when they're scrolling, scrolling through Hulu, or Amazon or Apple TV, or whatever it is they go, Oh, I recognize that. That marketing spend that I had called theatrical now causes them to click on it, and that creates revenue for me.

Alex Ferrari 34:26

Yeah, it's just about the model is is it makes sense but the ROI is the issue for me because for you to do a mark, if you can break even on the marketing spend, meaning that if you can break even on theatrical sales, whether that be through actual box office, or actually selling merch, or some sort of ancillary product lines while doing that screening at either conventions, or theatrical or whatever you do, if you can break even or actually make a profit at that point, then this model makes sense. But if you are losing money theatrically, and then you're hoping that people People that happen to pass by look at a poster, or yeah, you stick out. It's gonna be rough.

Ryan Templeton 35:04

Right! But you're not talking about a huge number at $2 million. Like you need 50,000 people to see this movie. That's a lot of people. 50,000 people Yeah, but it's, it's not a lot of people, if you actually turn these things into like events, if you're going to a city, and and you're running an event on a Friday, Saturday, Sunday, and you're going to be there for a q&a afterwards.

Alex Ferrari 35:26

Yeah, you're touring, you're touring. Basically, you're going on tour with the movie. Yeah, it you're, you're basically frankensteining, like you said earlier, you're frankensteining, a bunch of different models trying to put something together, that makes sense, you're taking the best of every little bit trying to put together this entire model. So I understand.

Ryan Templeton 35:45

So because there's multiple Alex's involved in this right one, Alex can be, you know, running their premier event in Philadelphia, and another Alex can be running at the premiere event in a different city. And you can kind of be grooming those those, those markets. And so after you've done that weekend, you've now saturated the market with, you know, maybe two or three or four screenings, and they've got to see you face to face. And there's a reason to come out because it's an actual event, they can get their photo taken. And you saturate that market with maybe 3000 People that are now out there talking about this movie, and they're bringing in new eyeballs. And then the theaters actually want to do a split with you. So if you had to, for wallet for just your little events, because they're like, we're not sure we're not sure that's fine you for a while, just that one. But the theaters need more movies, they just simply need more movies, and they need it for more demographics. And so if you say, like you're been saying, if you you niche down and you know that niche, and you know how to get to them, and you know where they live and where they are, and you can actually mobilize them to the movie theater, then you can put that in front of them. And then there's a whole reason for them to go out into their communities and say, you know, that niche I like, this is a movie about the niche that I like, and that's the word of mouth marketing, or what they call buzz, that actually brings new eyeballs to come and see that. And the the theaters love those kinds of deals, because a 5050 for them is a better deal than they're going to get from any of the studios,

Alex Ferrari 37:12

Right. And the thing is that again, everything you're talking about really does come back down to the riches are in the niches like it is about bringing niching down you're not doing for movies that are broad spectrum, like a romantic comedy, a generalized drama, you know, a generalized horror movie or something like that. You're creating very niche product for niche audiences within this model, which right now you've now now you're not hedging your bets even more, because now you have an audience that you can actually reach. As opposed to creating Oh, I'm just going to make a romantic comedy for $100,000 with no stars in it, and hope somebody finds it like that's you, you'll die. It's over, it's dead. But I do i

Ryan Templeton 37:53

But you got Sorry, what you need you niche down to a place where then you you provide them with material that they then want to announce correct as if if you niche down and it's only something that can be shared within the niche, it's really only got that narrow mountain. And you can do that and make money in directing, but the way but the way to make money in theatrical is actually to grab the niche, and then have the niche want to tell their friends who aren't in the niche about it. That's the word of mouth marketing. That's the piece that creates those 4x and 10x films, that then can carry your whole production slate, and so you're niching down with the content on the screen. But then, in this sort of model, again, if you're showing how the sausage is made on the backside of it, then those people feel the same sort of reciprocity for the person who's sharing that information with them. And they're potentially paying you here in your transactional video on demand or Patreon kind of style window. And then they're also paying for you inside your theatrical window and they're mobilizing themselves and friends, when you come to town with the events. And you you know, you talk about whatever it is if it's the vegan chef, right, you do the vegan chef seminar, you bring in the you know, a vegan caterer to the premiere? Yeah. You know, and have them sponsored the event. And those are the sorts of things that you do at but the you're not going to pay that vegan chef to come there. That's free marketing for them. They're gonna love that. Right. It's a it's a movie, but that's the thing about our business is it is the sexiest business, because everyone wants to be involved in it in some way, shape or form. And because it elevates everything you're doing now. Go ahead. Yeah, you have a question.

Alex Ferrari 39:39

You know, so it's, it's, we I want to just kind of reiterate what you were saying in regards to the, the kind of the reality show style process of explaining and showing you how the sausage is made, you know, to give everybody listening An example is my film on the corner of ego and desire. I've been talking about this movie for better part of two years now. At this point, and people have been asking me left and right, like, when are you going to release it? When are you gonna release it? I've been busy. I've been busy is coming out in January. But the point is that I've talked about this film so much, and it is so perfectly positioned for my niche audience that, you know, now people are dying to see it and also consume other products or other things that I'm creating about it. And I've already been I've already made money before the movie ever got released, because I've been able to create other ancillary revenue streams from just talking about it, because that's a model that I've been able to build up with indie film, hustle. And I did the same thing with this is meg my first film before then. So it is possible. But this is a long game. This is not a short play. This is a long game plan. And that's how filmmakers need to see their film careers.

Ryan Templeton 40:46

But it's a career. You're right. You're

Alex Ferrari 40:49

It's not a lottery ticket.

Ryan Templeton 40:50

But there is no filmmaker who doesn't want to make a career out of it. But you have to like it's exactly what you see, you have to play the game, we have to sit down and play several hands at the same time. And that showing how the sausage is made, like the back side of that thing is so valuable. Consider that like, how many people can't afford to go to film school, or any post secondary for that reason, for that matter. Now. That's an underprivileged underserved community. And we wonder why we don't have stories coming out in those communities. Why it is everything is homogenized through the lens of New York and LA, right, like, because those are prohibitively expensive cities to live in. Right? I live in middle America, I can't afford to live out in New York or LA, I just simply can't. And a lot of storytellers are in the exact same place. But there is no monopoly on story. There is no monopoly on talent. Right? La has got a real housing problem crisis, right?

Alex Ferrari 41:47

Tell me about it. I'm here.

Ryan Templeton 41:50

I'm here. Yeah, but it's too, it's too expensive to go there and do a startup business. That doesn't make sense. It, it makes sense. If you want to go and serve someone else's vision, who's already got like, you know, a strong foothold. But you're talking about regional filmmaking, with regional releases, and then you're making kind of these communities around those things. Are you familiar with them? Dunbar's number?

Alex Ferrari 42:16

I've heard of it. Explain it to me, please.

Ryan Templeton 42:19

So the theory of Dunbar's number is like, you can have close personal relationships with anywhere between you know, 203 100 people, these are the people that are your family, your friends, your co workers. So essentially, what you're doing is you're creating this, you know, within that 200, so you definitely keep some friends and family and keep you know, those things. But then the other people that you want to try and find are people that you want to work with people who are artists, people who are DPS, people who are, you know, willing to serve an idea, and you can all work together to, you know, rise, raise the tide. So you have your filmmaking crew, and you guys live to you, like you live in relatively in those communities, and you make films together, that's regional filmmaking, and then you amplify that into your, you know, little network again, and that network is going to be, you know, 2000, once you get away from that, first, the first 200, or 300, that you can actually have, there's only about 2000 people, because you're going to all have shared connections. So there's only about 2000 people around that community that you call that your tribe. And your tribe is probably bigger, because you've got other people pulling you in. But ultimately, like the real, real hardcore ones, the Evangelicals for indie film, hustle is probably about 2000. And that's enough to create like a sustainable living for one person. But what you're trying to do is expand that over and over and over again. And by creating the content around these 200, and then making a 2000. It's the same thing, the film itself becomes this 200 thing, you need to find those 200 evangelicals for this film, they're going to create these networks around them. So you can create them in different cities. And you can kind of make this tour with your film, all of a sudden, you start being able to feed the whole.

Alex Ferrari 44:05

The thing is that the one thing that I would like to add to this model that you're talking about is that the unlike the olden days, where you had to go around on a tour like this to make money, which you still can, but now these these, these content can live forever, on line. So for me, I release a immense amount of content, but my catalogue of content is watched and listened to every second of every day someone's listening to something or watch something I've done or read something I've done over the course of the last four and a half years. So every day that goes by I add to the catalog. Now the big difference is my addition to the catalog is extremely affordable because it's a podcast, it's an article, it's a video, it's nothing that's cost me hundreds of 1000s of dollars. So if it's right for filmmakers, it's a little bit more costly, but if you start building this this kind of ecosystem, which includes articles includes videos on YouTube includes this kind of ecosystem of products and services that are dedicated to a niche, then you could start slowly building up a business. I mean, I didn't just wake up and, you know, have 4 million downloads or 5 million downloads on my podcast, like overnight, it took years of work to do. And it still takes a lot of work to keep that going. But it's given me the position where I am now where I can go out make a movie, I could write a book, I could do whatever I want. And I'm very happy and grateful for that. And that's where all filmmakers need to come to, they have to build this kind of ecosystem business for themselves. Or if I may, say, a film entrepreneur, like business, around their art, so they can constantly constantly do it. And to a point where the movie, if they're smart, the movie almost becomes a lost leader. If they've created a good amount of product and services around it, were at the beginning, you you're exploiting the movie for actual revenue from the film. But like many examples I talk about in my book, where the filmmakers literally give it away now, they're like, just take it because I know when you watch it, you're gonna come over here, because you're interested in my niche, and look at all the products and services and information that you're actually looking for. How can I be of service to you? And that is the key of filmmakers moving forward, in my opinion.

Ryan Templeton 46:20

Yeah, and, and, and if we look at this, again, let's go back to like the problems that are actually in the marketplace, right. So you take that thing to the theaters or, or you haven't, you don't think that it has theatrical legs, but you've already started to drive an audience to it. Well, guess what, that is now valuable to who, to streamers. Those people who don't have your subscribers already, guess what, when your film goes to their platform, they'll pick up the subscription of, you know, Paramount network, or they'll pick up the subscription for peacock or whatever it is, just watch your film, now you've actually tangibly moved the needle for that business, and it is part of their catalog. That's what those businesses are, right? It's just a giant catalog, they're not really producing their own stuff, for the most part, they're putting money into it. But what they do is they put the money into it, and they hire people in a service agreement, basically all over the country, they go and find the best tax incentive, and they drop the money in there recoup a piece of that tax instead of and so they're reducing the cost of what that that is, and we here in Utah have High School Musical, which is on Disney plus. And we have Yellowstone, which is on the Paramount network, and those are running on. And those are relatively big franchise properties. And it's being done by all my friends, like, it's just people that are in our community, who we rub shoulders with, you know, you see all the time. So you can take those same people who now have pedigrees of working for these major studios, and why not make a business that has those professional resources, if they're good enough professional resources for those big major studios, then they're definitely good enough for your independent films, rally those people together and create the business model model around that. And then if you really want to, like, give an opportunity to another group of people who are underserved, there are investors who actually want to invest in films, and who are not allowed, because if you have the major studios who create these slides of films, so you know, like I said, Disney's going to do 17 films, so they have one giant equity fund, essentially, that's capturing all this money from their private investors. You're either in or you're out. And if you're out, you're basically out forever. So you always have to put this money in doesn't matter what's in the slate of films. But those things make money, they have $5 billion box office returns this year alone. That's, you know, ridiculous. So yes, you want to put money into there. But other investors don't get the opportunity to invest in films that are going to have recognizable talent, and a theatrical release and have some measure of quality. People want that. They want to invest in that because that's fun, it's entertaining, it's sexy, and it's entertaining and, and they want that, but they want to do it prudently. So you diversify the risk by doing it in a slate deal with them. And so you're, you're mitigating their risk. I would never ever, ever, ever, ever advise someone to invest in one single film because that is super dangerous, right? It's super risky. You can lose, you can lose not one single act of God or you will, you will lose it all.

Alex Ferrari 49:39

I mean, it's 2% of film, independent films actually make their money back and there's a reason for that because you're putting all that pressure on one film to carry all the weight where if you if you take like I said, if you have $500,000 you make 10 to 12 movies off of that, which is doable and still very respectable budgets anywhere between 45 and 50,040 50,000. dollars per episode, which I know a lot of people don't, how can you make a real movie without like I've made to that, and they both sold and they're both making money and I don't care. So it's all depending on the kind of stories you're trying to tell. And if you're in within a niche, imagine if you had an the vegan niche, and the vegan chef movie, and witches, by the way. But by the way, there's an entire chapter of that in the rise of the entrepreneur, it's called the vegan chef, and I just broke it down. By the way, I have a name for it. Now it's called Crazy Sexy vegan. So it's just called Crazy Sexy vegan, why not? It's called crazy, sexy vegan. Imagine in that niche, or the surfer niche, or the skateboarding niche. If you made if it was a niche that could support multiple film, imagine if you made 10, vegan themed or plant based themed movies. And you can include some documentaries in there you and imagine you had a slate of those, do you know how much money you would make with those when a movie like game changes just showed up? And just it was the number one documentary of all time on iTunes. And Netflix paid an obscene amount of money to have it two weeks after that original release. You know, that that that demographic is that niche is huge, or a surfer, a bunch of surfer movies, or a bunch of skateboarding movies are a bunch of trombone movies. I don't think that's going to work. But you know, but there's those kinds of films, imagine if you played a slate as opposed to one, one.

Ryan Templeton 51:21

Yeah. And that's and that's exactly what you're doing is you're diversifying the risk for the capital, right. And so then the money wants to invest in this thing. And then, so you have people at the front end who want to invest in a diversified portfolio, because it's going to be fun for two years to have a new movie, every six months, you're getting to go to a film premiere, you can invite your friends, you can bring your family, you get the red carpet treatment, like it feels fun, that's a good use of your money, and you're supporting a local community of filmmakers. These are the people who live within your region, and you want to support them, because they're artists and heaven forbid, you know, you know, you don't get to tell the stories, that of your community and the niches and things like that, that you're involved in. But then you can even now do the business model of the online public offerings, which is the equity crowdfunding, and you had an episode not too long ago about that, which I highly recommend people go back and listen to. But instead of doing the equity crowdfunding up front, you do an equity crowdfunding when the film is done to support your theatrical. So now, I have a film where I'm showing you the key art, I'm showing you the publicity, I'm showing you, all the behind the scenes and the special trailers and things like that, then I create this fund that says, Look, you put 300 bucks in here, and I'm going to share my box office revenues with you. And that's basically your piece of this, that this film. So now what have I done, I've created an incentive, a financial incentive, where they've invested their $300 into this movie, now they have a $300 incentive to broadcast this film to as many people as possible. So I share with them all my Dropbox with with all my all my assets, and they can hit their own audience with it. So then you've created an avenue for people with larger followings, like yourself or other YouTubers or other people with like niche audiences to financially back you. And then also return on that investment because now what you know your mobilization right, wait 300 bucks, oh, yeah, I can send 3000 people to cities across the country, that is going to turn back your money. And you do that just in a few small things with this film. And now your de risking what your theatrical risk goes down your PNA spend comes down. And the filmmakers are de risking themselves in theatrical space, sharing the box office with the audience who will actually mobilize to go and see it.

Alex Ferrari 53:52

The key though, to this entire conversation is to keep the budgets low, to keep the cost of the product low. And that's what I keep preaching again and again. And I was talking about it at AFM when I was there last week, where you you I talking to filmmakers, and like I did, I talked to a couple filmmakers are like how much do you need? Like, well, I have a quarter of a million dollar movie, but we need a million. So I'm like because you have a quarter million cash. Yeah, yeah, we have 250,000 now, but we need a million. And they had this whole package and everything. And it was an I don't wanna talk about exact What kind of movie it was. But it was a movie that and I told them I'm like, do you want me to tell you the truth? And I say yeah, like, you need to make this movie for $75,000. And if you're smart, you'll make two or three movies with that $250,000 If not five movies with that $250,000 Because you're gonna spend another seven years chasing the $750,000 and you won't be able to make money back with this. I promise you, you just like Oh, who's your cast? What's your theme this and it was just it did not pass the mustard. So if you drop that budget as low as possible, and I would I always tell people as well, when I had people that I talked to go look, if you have $30,000, you're like, I know you want that techno crane shot. But can you get away with it? Like, how much does that techno crane add to the bottom? Yeah. What's it worth, it's like, again, I'll go back to my olive oil. So if I have a bottle in my bottle is gold. It's golden bottle. It's made of pure 24 karat gold, it still has olive oil in it, and has a diamond and crusted cap on it or a cork on it. Okay? How much more money am I going to generate? How much how much more revenue can generate by adding really embellishments that the core customer doesn't care about? You know, like, one or two people are going to buy that I'd love to meet these people. But so there's someone's gonna buy a 24 karat bottle of olive oil? Sure, someone will always buy something. But in the long term, does that techno crane add any more dollars to your bank account? Does it add any more Adi? Like, can you tell the story in a slightly more affordable way? I know it's nice. Look, I've shot with a techno crane. If I could live on a technocrat I would it is wonderful. But does it make financial sense to occur that,

Ryan Templeton 56:13

Right and that's the end, that's the calculus that filmmaker you know. And when we're in art mode, like when we're in art mode, I don't think that we actually should be thinking too much about that, like we really should create from a space of purity. But then like, when you take your first steps back, like you need to go, Oh my gosh, this is so not going to happen. So either I have to do something else, or I have to make this fit within the resources and things that I have in order in order to create. But I guess the point that I really want to like emphasize is that this community idea, and that community of face to face, and working with people creates these regional pockets of the film. And those things can live just in those regional areas. There's filmmakers here in Utah, that have been doing this for 1012 years living off living off of just like

Alex Ferrari 57:07

The regional cinema model, the regional center model,

Ryan Templeton 57:10

Regional cinema model, and then they are releasing it just to the small pockets and niche communities in this area. They have been doing that for 10 years. So now what I'm now what you're saying is to build on top of that, that's what you want to do is build on top of that. So now you are bringing in people who want to be involved in the film business. Imagine if at the front of your theatrical screening, you had, this film is brought to you theatrically by. And it's all the people invested in your equity crowdfunding campaign, their Twitter handles or whatever share their businesses are, that is a huge value to someone because it's entertainment, which is what captures eyeballs and attention. And that's what people absolutely want in their businesses. And so you don't need to spend a huge amount of money that $250,000 filmmaker, right, they're already at the point where they can make a million dollar movie because the magic formula is 25% in capital 25% in debt 25% in pre sales 25%. In incentive funding. Now pre sales is going away. So what you're gonna do, it's gone. It's gone. So you've replaced that piece with equity for your service positions. Everyone dials down their cost,

Alex Ferrari 58:23

Right. But the thing is $250,000 in today's marketplace, in today's tradition, the old traditional model is destroyed that by the time this episode airs, I've already released that episode. But it's gone. It's official. Now it's efficient, not like literally the traditional film distribution model is dead. It's dying, a miserable death and people are trying to hold on to it. It happened in publishing, it happened in the music, business. It's happening here. The model of making money with the art in this industry is changed just like it did in music just did in publishing. It's just adjusting. It's a it's a titanic shift in the way we do business and the way we create art, and people really need to understand that and real quick, I want to go back to what we were saying about if the techno crane makes sense or not. Do you remember the you ever hear the story of Michael Bay on bad boys? For that one shot, you guys. Alright, so Michael Bay, his first movie was called Bad boys with Will Smith and Martin Lawrence. And he had no power because he was still just a commercial director. And he wanted to there was a scene in the movie, which I just recently saw so much fun. There's, there's a scene in the movie at the end, where there's a big shootout with all the drug dealers in an airplane hangar. And there's one scene where one of the villains explodes out of the airplane that's parked and it just explodes in a fiery ball of flame into like, explodes out of it and into like a pile of get whatever. He wanted that shot. He wanted that shot so badly that the the line producer wouldn't give it to him. And he's like, what would it cost to come in tomorrow? Early for two hours and get that shot? Shot, and they did the numbers and it was $60,000. To do the shot, the one shot it's on screen for three seconds, four seconds, right. And he paid for it out of pocket. Because he is an artist wanted that shot. Now on a, you know, in there's arguments on both sides here like, did he have to do that with the movie had been successful without spending that $60,000? Yes. And there's no doubt in my mind, the movie would have not lost any box office whatsoever without that shot, but the artist in him wanted to do it. But you know what he did he ponied up his own money to do his art. And that is the big difference that filmmakers don't get. If you want the techno crane, and you want to dig into your credit card, because you want the techno crane shot, and the production can't afford it. Go for it, but understand what you're doing.

Ryan Templeton 1:00:50

Yeah, and this, and this applies to all artists, right? Like, I'm an actor, right? If I get a good script that comes, it comes to me, and I'm like, This is amazing. You pay me just to keep me alive. And I will defer everything else. And other actors are no different. Now, their managers or their agents are going to say no, don't do that. Right. They're gonna say no way. Don't do that. Because for them, they get their percent of their percentage, yeah, their percentage, and then also their publicist and their lawyer. And you know, by the time it gets to them, they're making 40 to 40 cents on the dollar.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:24

10 million doesn't go as far as it used to you only take home maybe three, 4 million after taxes. I mean, it's not really who can live off of that, really.

Ryan Templeton 1:01:33

But independence can go to actors. Yes. And they do all the time, go to an actor and say, Look, I want to pay you a SAG minimum deal to work on this film for however many you know, it should weeks or three weeks, trying to shoot them out as fast as you possibly can. And they will say yes to the things that they think are good. If you've bought a strategy to put that into the theater, then you give them box office bonuses because they are the vehicle they are that the protagonist or antagonist or whatever it is that they're playing in your field that people recognize, that's their brand, and you double them up every time you double up or you give them a you know, the first take off the top in order to get them home. Because at the end of the day, they are artists as well. And that's their sacrifices to work at a lower rate to work on your film. And everyone will do that. It's the the problem is when filmmakers take advantage of people's passion, and say do it for free. And that's a real problem. And there's a lot of filmmakers who don't know how to say no, there's a lot of crew people who don't say no, there's a lot of actors who don't have to say no, because they're being given an opportunity, but you can't live on zero.

Alex Ferrari 1:02:43

You know, without question without question, I neither, you know, when I make my films, I either pay the minimum hour, I give them some value that is worth their time. Whether that be a service, whether that be an exchange of services, whether that be there's something that I give them that that they're willing to do the work for. And it's also I'm not working 20 hour days, it's a lot of things about it. But the one thing I also wanted to say here is that the what we're talking about is with the actors and you know, coming up peace, everybody is becoming everyone's becoming a film Japan or whether they know it or not every all the actors or the crew people to distribute the distribution and everyone's becoming entrepreneurs, you have to become entrepreneurial in the way because the old model is broken is breaking down, if not broken down completely already were stupid, where actors aren't getting $30 million upfront anymore. Those days generally are gone. For the most part. There are exceptions, of course. But I remember that remember the whole days, like when people were paying three $4 million for a script. And then and then you know Arnold was making 25 million for Batman and Robin like those days are gone. Now there's back in participation. There's gross points, there's they're working, they're partners with the studio, and they're leveraging their own fame and talent with the studio's money in marketing, because they understand that. And this is a shift that happened in the in the music industry years ago, where there is very little money now in the music. Like yeah, there are the record sales, and the publishing money that you used to get is not what it was before. Like I wrote an article where, you know, for REL, the the artists who did happy, everyone that song, do you know, I didn't know I'm not gonna do that. He played that movie streamed on Spotify a billion times a billion times is streamed. He owns the right on he's the publisher on that. How much do you think he made on publishing offers off of off of Spotify?

Ryan Templeton 1:04:42

Wow, man. Have a billion a billion of Yeah, but it's so minimal. It's minimal because it's going to be a fraction of a penny back. That's 2 billion.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:50

So how many how much do you think I'm gonna say? It's gonna make it bigger.

Ryan Templeton 1:04:55

So just just under a million, yeah.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:58

$1,857 He made off of publishing $1,857. Not the sales, not the stream. This is the publishing aspect of it. He might have made more off the streaming but it was not much that was made some money. But the publishing we're publishing used to be gold used to make obscene amounts with publishing $1,800. He does a whole article, he's like, I can't argue, if a billion dollar of a billion stream saw makes $1,800 what hope is there. So the the money is not in the music anymore. The money's in the brand, the artists, the ancillary product lines, the sponsorships, that's what they started doing. There's bands that go on to touring, because you can't bootleg a tour, you know, you get bootleg that experience. So now I heard bands who are selling VIP tickets, where you can come backstage for like 250 bucks, get an autograph, and a picture with the band after the show. And that's how they're making their money. Because their access access is uncommon. It's insane.

Ryan Templeton 1:06:01

And it's and the collapse of that industry, though, is actually quite sad because you see artists who are creeping up into their 70s and they're at still on tour because they never quite hit the threshold to retire. And so the Rolling

Alex Ferrari 1:06:15

Stones are doing the Rolling Stones. I mean, Bon Jovi is not correct. I'm not gonna for Bon Jovi Rolling Stones, Aerosmith, they're all doing fine, because they were good, and they're fine.

Ryan Templeton 1:06:23

But it's the ones that it's a little bit lower tier, the ones that have been grinding at it for years. And

Alex Ferrari 1:06:28

I just I just saw that poison Motley Crue. And I think somebody else joined force, Guns and Roses, like the three or four of them for a worldwide tour, which this gonna do fantastic. But that's they have to make the cash man.

Ryan Templeton 1:06:43

Yeah, well, you're seeing a lot of the, the middlemen in every in every position goes away. Right. So it's the people in between the film and the theatrical exhibitions, the people in between the film, and the, the TVOD, or the streaming. And we have that example of distributor aggregator actually just an a relatively well established aggregator going under. This is you know, you're seeing this crunch and it's happening in the industry between the the studios right now and the WNBA even right, because their packaging material, those middlemen are creating that that conflict of interest in the at the ATA and the WG are going at it right now, essentially. And the Go ahead.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:29

No, I was I was about to say this exact issue is what came up I actually got a few people asked me what I thought about it, which was the the like, they got rid of this whole Law of the anti What is it the you can't film studio can't be a theatrical distributor. And they finally got rid of that. And when I when someone asked me like, didn't they already get rid of that? I mean, Netflix 80s Yeah, like nothing. I mean, it was still on the books. But yeah, no one enforced it. Because the second that Warner Brothers was making content for HBO, will that broke that and Netflix and their direct relationships. And that is where everything is going. The theaters that the studio's don't want to deal with the movie theaters, if they can make the money going directly to Disney plus, if Disney can make money going directly to Disney Plus, they won't go theatrical. They if they don't need to share 3040 or 50% of their take, where people are going to show up because, look, you know, right now frozen to the only place frozen to could be seen is Disney plus, I promise you, that'll jump 30 or 40 million subscribers in the course of one weekend. Now will they stay? That's the job of Disney plus to keep you there. But if they start every imagine, just imagine a world and I know this world is coming. Imagine a world that now the new Marvel movies, the new Star Wars movies, they're all designed for the direct output because they don't need to go theatrical. And if they do go theatrical, it's kind of like a specialty event or it's not the main revenue source. It's happening already. It's already happening. I don't know if I don't know if you've heard this and I've said this publicly before I'm not sure that I heard through the grapevine that Disney was showing a lot of their people how they actually made money with their movies. So it was quadrants. It was like box office. It was DVD blu ray home video, and merchandise. And when they came to frozen, it was like an 8010 10 So it was like and that made a billion dollars in the box office. So was a billy box office like a billion or so in home video DVD streaming all that stuff. And then 90% 80% was on merch and then do you know how much and you know how much they made off of the dresses. Just the dresses, the frozen dresses, just the frozen dresses alone, how much they made a billion on the dresses just on did not the other obscene amount of merchandising for frozen. Just the dresses was a billion dollars because that's what they that's what they care about. That's what that's where the money is, man. That's what the money is.

Ryan Templeton 1:10:00

Yeah, and that's why and that's why the theatrical is actually important because it elevates your voice. So now you actually have perceptible value to all kinds of other merchandise creators, who then would come to you and say, let me license this ticket on my mugs. Let me license it to put it on my shirts, let me license this in order to, to create dresses are whatever that piece is. But you have to get to that, that saturation kind of point where people know that you exist. And the theatrical space is the way to do that. And if the current leaders

Alex Ferrari 1:10:30

Currently who knows what's gonna happen,

Ryan Templeton 1:10:32

But here's the thing is like, we don't stop going to sporting events, because we can watch it on TV, we still go to just the cost of going to it is going to goes up, right? And that's what's happening with the theatrical space. Like there's something magical about being showing people screaming and yelling at your favorite team. It's the same thing in the theaters, right? You need to feel like you're part of a community. So that's not going to go away. It's just the cost of going to the theater is going up. And we're seeing that, because like you were saying the ticket sales are going down. But what's happening to the revenue numbers, they're flatline, they haven't gone down in years, because the price because the price gives price goes up. Yeah, it goes up based on the number of people and so but that's why you're seeing nicer recliners, because there's fewer people, you're seeing recliners, you're seeing food show up, you're seeing better screens, you're seeing better sound because now I've got to compete with every home theater system in the entire country, I got to blow those guys out of the water to make this an experience that's actually worth your full subs, your full monthly subscription to, you know, Netflix or Amazon or Disney plus, because this is an experience. And that's the that will never go away. That experience will never go away. Because we will have to have we have to have human contact as human beings.

Alex Ferrari 1:11:44

Yeah, please haven't gone away. You know, Broadway probably still doing gangbusters. So you know, and you know, that, arguably do you need to go see a play now. Because you have to be entertained at home, but it's an experience is a different kind of art form and so on. So I agree with you. I don't think theatrical is going to go away completely. But it will morph into a new thing that we don't recognize right now. Yeah, we wouldn't recognize

Ryan Templeton 1:12:05

And there are smaller exhibitors smaller theatrical exhibitors are hurting badly the content right now. Yeah, and, and it's because there's no dollars upfront, to get into independent film to allow for someone to control their own destiny through this theatrical space. And so you really have to look at the whole game, from end to end on like how you can actually play this game, and create strategies for that, like I have my strategy, and then it might not be the strategies for everybody, right. But at the end of the day, like the whole point of, of, you know, independent filmmaking is to create a story that then other people can get rally around, like, the purpose of art is not to create art, it's to build communities and relationships and give people a reason to talk to each other who wouldn't otherwise talk to each other as a mess apart.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:56

Amen. Brother, amen. Preach it a preach it, preach it. So I'm gonna, because we could talk for another hour about this, but I'm gonna, I'm gonna ask you a few questions that I asked all of my guests are, what advice would you give a filmmaker trying to make it into business today?

Ryan Templeton 1:13:13

Storytelling, focus exclusively on storytelling, but in all phases of storytelling. So you can storyteller on the page, which is the one that we always think about when you can chuck straight pelvis storytelling on the, on the screen, and in post production, but their storytelling that can be done with data. I'm using the data points of my film to tell a story in order to create a narrative. So understood, investors understand what it is that I'm actually talking about. That's a narrative focus on that storytelling, focus on the storytelling of marketing. Why it is people need to get up off their couch and actually experience this event and go to this theater at this specific time, and be a part of a larger community. tell those stories focus on that kind of storytelling, because the better you can get at weaving those narratives, not just in the three phases that exist in film, but in all the swirling stories that go around it. So when you go out and you do your publicity, all those things, you can be telling good stories, because that's ultimately what makes someone want to can engage with you.

Alex Ferrari 1:14:16

Now, what is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film business or in life?

Ryan Templeton 1:14:21