What is “Hybrid Distribution?”

Hybrid distribution is the state-of-the-art model more and more filmmakers are using to succeed. It enables them to have unprecedented access to audiences, to maintain overall control of their distribution, and to receive a significantly larger share of revenues.

Today on the show we have a legend in the ultra-low budget indie film world, Peter Broderick. He coined the term Hybrid Distribution in his seminal article Declaration of Independence: The Ten Principles of Hybrid Distribution. Peter also wrote a very informative article detailing ways filmmakers can deal with the Distribber debacle and protect themselves if a distributor goes bankrupt. Read that article here.

Here are the Ten Principles of Hybrid Distribution:

- Design a customized distribution strategy

- Split distribution rights

- Choose effective distribution partners

- Circumscribe rights

- Craft win-win deals

- Retain direct sales rights

- Assemble a distribution team

- Partner with nonprofits and online communities

- Maximize direct revenues

- Grow and nurture audiences

These principles of hybrid distribution emerged from the experiences of hundreds of filmmakers. Here is a bit on today’s guest. Peter Broderick is President of Paradigm Consulting, which helps filmmakers and media companies develop strategies to maximize distribution, audience, and revenues.

In addition to advising on sales and marketing, Paradigm Consulting specializes in state-of-the-art distribution techniques—including innovative theatrical service deals, hybrid video strategies (mixing retail and direct sales online), and new approaches to global distribution.

Broderick was President of Next Wave Films, which supplied finishing funds and other vital support to filmmakers from the US and abroad. He helped launch the careers of such exceptionally talented directors as Christopher Nolan, Joe Carnahan, and Amir Bar-Lev. In January 1999, Broderick established Next Wave Films’ Agenda 2000, the world’s first initiative devoted to financing digital features.

A key player in the growth of the ultra-low budget feature movement, Broderick became one of the most influential advocates of digital moviemaking. He has given presentations on digital production at festivals worldwide and written articles for Scientific American, The New York Times, and The Economist. In 2004 Broderick launched Films to See Before You Vote, harnessing the power of film to impact the US presidential election. He is a graduate of Brown University, Cambridge University, and Yale Law School.

Now focused on the revolution in film distribution, Broderick gives keynotes and presentations internationally, most recently in Amsterdam, Sydney, Toronto, Cannes, Guadalajara, Berlin, London, and Rio de Janeiro. He served as Program Co-Director of Digimart, the global digital distribution summits held in Montreal in 2005 and 2006. He teamed up with acclaimed filmmaker Sandi DuBowski to design and teach a master workshop in documentary distribution and financing at the Doc Aviv Film Festival in Israel.

Enjoy my eye-opening conversation with Peter Broderick.

Alex Ferrari 0:40

Now today on the show, guys, we have a legend in the film distribution space. His name is Peter Broderick. And he wrote an article back in 2009, coining the phrase hybrid distribution. Now what the hell is hybrid distribution? Well, hybrid distribution is the state of the art model, more and more filmmakers are using to succeed. It enables them to have unprecedented access to audiences to maintain overall control of their distribution and receive a significantly larger share of the revenues. Now Peter is a champion for independent filmmakers. He's been doing this for quite some time. And I wanted to bring them on the show not only to dig into hybrid distribution, but you also wrote a very, very informative article about how to deal with a distributor going out of business, how to protect yourself from something like that, as well as digging a little bit deeper in how to protect yourself and what to do next. If you are caught up in this distributed debacle. And Peter is a wealth of information, and we sat down and the interview just kept going, guys, it just kept going. We have it was just like two guys sitting around talking about how to make money in this business. And it I think it goes over an hour and a half. So it is an epic episode. But man, are there a lot of golden nuggets of knowledge bombs in this episode. So prepare yourself to get your mind blown, take some notes, and enjoy my conversation with Peter Broderick. I like to welcome to the show, Peter Broderick thank you so much for being on the show. Peter.

Peter Broderick 3:24

Thanks for having me, Alex,

Alex Ferrari 3:26

I appreciate it. You are You are a legend in many ways in our industry, and especially in the distribution realm. So I've heard your name fly around for years and years and years. And it is taken this disaster called distributor to bring us together Finally,

Peter Broderick 3:45

There you go.

Alex Ferrari 3:47

So how do we? Exactly? Well, I mean, you know what, to be honest with you, this whole dish, and we're going to get into the whole distributor thing. But this this debacle in this this situation, it has brought a lot of filmmakers together, and a lot of people together in a way that I don't think this this kind of tragedy would have wouldn't have been able to it would wouldn't, there would be no other way to do it. It didn't sometimes it takes a tragedy or takes, you know, an explosive situation to actually galvanize a community and put them in a game together. Would you agree on that?

Peter Broderick 4:18

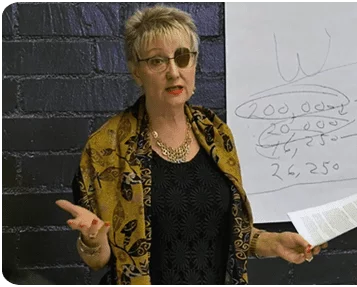

I totally agree. I think that sometimes when I'm speaking, and let's say I'm looking at 200 independent filmmakers, and I think about how atomized their experience and information is they're not sharing with each other. And I think if we could just figure out ways to share how much more powerful everybody will be. And so in the distribute situation, you know, with the Facebook page that's happening in a in a great way and so I hope there'll be more of that to come.

Alex Ferrari 4:48

So before we get deeper and deeper into the distributor situation, how did you get into the business? Can you tell everybody a little bit about yourself in your in your history in the business?

Peter Broderick 4:58

Well, it's there's There's, there's so many chapters, but I'll just do the Haiku version for show in a former life, I was working as a public defender in DC. And then after three years, I decided I had, I needed to find another happier line of work.

Alex Ferrari 5:22

So you jumped into the lucrative, lucrative world of filmmaking.

Peter Broderick 5:26

Well, lucrative. It wasn't about lucrative, lucrative business, it was about passion. And I came to Los Angeles, I was still living in in dc, dc. I did 55 interviews in five and a half weeks, I mean meetings, you could send out interviews. And then on a fateful Friday afternoon, I got three job offers in two hours and met with the people on Monday, and then started working for Terry Malick on Tuesday. So the days of heaven was in post production. And so they were going to do some additional shooting. So he asked me to organize that. And then I was living out of a suitcase with seven days worth of clothes. all my stuff is in Washington for months. And then eventually, I got to go back and, you know, drive out here with with everything. And then I worked for Terry for four years, in the second part of that time, we did the initial shooting for what became tree of life. And Terry put the footage in this in a room literally in a refrigerator. And then, like 30 years later, thought it out. And it's actually in a tree of life, which is kind of remarkable and, and only Terry would would think of that and make it work. So I and then so I stopped working for Terry. Then I started consulting for various foundations about uses of new technology related to film. Then I got on the board of what was then called IP West, now called film independent. And I wrote a series of articles about ultra low budget filmmaking. So it was clerks, El Mariachi, a number of other films. And it was really about how you can work backwards from resources that are available to you. And then write a script that can be made with resources you already have. So you're not chasing money endlessly. And we printed the budgets, which is a kind of as you know, revolutionary act to print a real budget. And, and those articles, there's they're still, they're still connected on my website, Peter Broderick comm had a really big impact. And so more and more filmmakers, not just across the US, but around the world started making ultra low budget features. And it was a it was just amazing that people weren't, you know, spending forever, chasing the permission to make a movie that could go out and make it

Alex Ferrari 8:19

But when you brought this idea of backing into or backing into a movie script or backing into the idea of trying to make a feature film, there was nobody who said that prior to that, or at least, there wasn't it wasn't out in the

Peter Broderick 8:34

In the mid 80s, there was a lot of money that came from home video. So it wasn't that hard to find a million dollars to make a first feature. By the late 80s. The bloom was off the video store rows and the shelves are full. And so you couldn't you couldn't find that million dollars anymore. So then these filmmakers started to do it another way. And I think what what was so exciting about it was the idea that they didn't need permission. They just needed to be smart about resources and write something that could be done with what they had. So in the case of El Mariachi, Robert Rodriguez had a gun, a school bus and a dog. They're prominently featured in the film, Kevin Smith was working at a quick stop, knew that at night, nobody was using it to go he could set it it's the funny thing about clerks is that there's this running gag when they come into the store and the blinds aren't up. The shutters aren't up, and that's because it's night outside. you'd realize that. So, so that was exciting. And then one day I was having a meeting with someone who was on the board of if you asked and he asked me what I was what I was interested in doing and he had evidently had a long lunch. He was being very sleepy in the meeting and finally while he kind of wakes up and he says and what else So I said, Well, I'm interested in starting and finishing funding for ultra low budget films, because everybody's running out of money. And, you know, so he goes, I'll help you do it. So, over the next year, he helped me write a business plan. Then, when the business plan was finished, I kind of assumed, okay, now we have a business plan. Now the money's gonna show up. That's true. So there's two quick stories. I was on the west coast. And there was a guy guy who was head of a record label. And we went to him and told him about the idea. And he loved the idea of giving filmmakers you know, their chance to, to start their careers. And it was a great meeting. And then a few days later, I found out that he was in a divorce, fight with his wife, all his assets were frozen. And last I heard he was in rehab. And that obviously went away completely, right? That I was in Washington, DC, and I ended up in this room with these rich guys. And I was telling them about this idea of a finishing plan, but they didn't know what independent film really was. They weren't quite sure. Finishing fun work. So I go outside in the hallway, the number two, the number one guy in the firm was traveling, the number two guy comes up to me, he says, We hear a lot of pitches, but we think you know how to make us money. Well, I was I was, I was glad that's what he thought I wasn't convinced it was the money making operation. But if you believe that, that was all good. So then I went back to Los Angeles, and he called me and he said, number one guys back in town. And he'd like to see some examples of these independent films. So obviously, you know, that's a trick question. If you send them the films that you like, they might run screaming from the room. And if you send and it's, if you don't do that, maybe when it comes time to finance a movie, they're going to not be interested in what you want to do. Anyway, so I sent him El Mariachi clerks. She's got to have it. And he got him on a Friday. And on Monday, the number two guy calls me and says, number one guy, watch some of those films you sent. There's a little pause. And then he says he never wants to be involved in any way. Which I thought was a pretty definitive No. better, better to have it then then have, you know, be in business with him. So that they went away. So then I see the independent film channel, IFC Films, heard about it, and they were interested because they were financing features by more experienced Indies. And they loved the idea of, you know, people just starting out. So an X wave films came together really, really quickly. And we had an advisory board of these fabulous directors from around the world. George Miller in Australia, Peter Jackson, New Zealand,

Alex Ferrari 13:12

Small guys, small guys. Yeah.

Peter Broderick 13:14

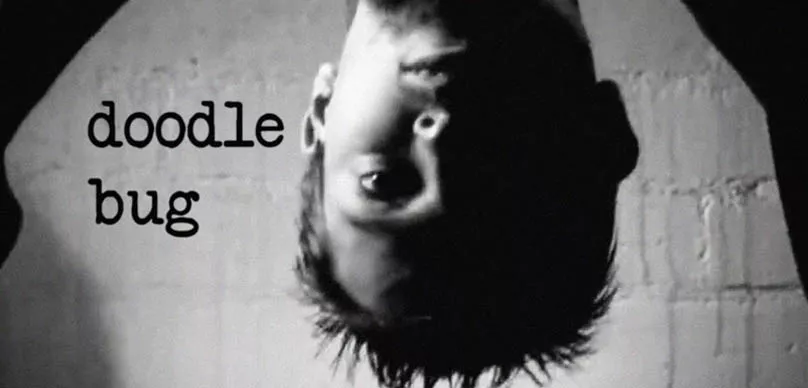

And Steven first, everybody just said yes, because they loved the idea of giving folks to chance. And so we started and the second film we did was a film called following, which was Chris Nolan's first feature. And that was, that was a really fortuitous thing. I went to a panel, Chris was on the panel. I never heard of Chris before. And he said he had he was making this film. So afterwards, I went up to him, and I wasn't even thinking about finishing points. I was just interested. And he said, Okay, and so he gave me a cassette, five minutes, and I'm like, this guy's got it. There's just no question. Whatever it is, he's got it. And so we gave them we gave him finishing funds, took the film to the Toronto Film Festival where it did really well then it won the Rotterdam Film Festival. And then Chris was off to the races. It was like guys distributed it got great reviews, and it gave him the opportunity to get funding from the mental and you know, on from there, but the film cost $12,000. shot and 16 the whole crew could fit in an elevator. And it's a remarkable movie, I think still. So that was a great, great story. Because really, what we want to do is not just help a filmmaker, finish a movie and find distribution but also help him or her launch their career.

Alex Ferrari 14:38

So you have a very you have a long past in this business. You've got some shrapnel. I feel that you have some shrapnel and some scarring. Without question from this business.

Peter Broderick 14:52

Well, I feel lucky. Really. I mean, the chance to work with Terry

Alex Ferrari 14:58

Its not a bad first job

Peter Broderick 15:01

Amazing. And then, you know, with the finishing fund, you know, we were kind of in new territory, finding, you know, exceptional filmmakers and films. We did a, we did a digital arm called agenda 2000, which was to give money to finance digital features, we were the first company to that was able to do that. So I've just, I just feel, you know, lucky to have to have these opportunities. And then when? Well, okay, so the next next thing that happened, I went to Cannes was 98. And I saw the celebration and the idiots have shot on cameras designed to take pictures of babies first steps and show them on the legroom television here, world's most prestigious Film Festival there on the giant screen of LA. I'm like this is this is a revolution right here. And so I came back to the US and was talking to my team and they said, Why don't we create a presentation and then take it festivals and show people what's going on. So we did that. And we took it to Sundance, Toronto, Cannes, Rio many places. And at first people thought we'd lost their minds, that it was filmed forever, and whatever. And then, all of a sudden, within six months in terms of submissions to the finishing plant, we saw the change. And Kodak, which I've been very friendly with, they thought about financing the finishing plant initially, but they only wanted to finance one movie. And I said, I'm sorry, I'm not gonna let the success or failure of this depend on the success of one film. But it was too risky for them in their own minds to do more than one. Anyway, so then they'd Kodak decided I was the devil. Because I was talking about digital filmmaking. And I said, Well, no, I think codecs great, but I think you should reposition yourself as the image company. It's not about film, it's not about digital, you do the best images, whatever, however, people want to work, but that they couldn't, they couldn't turn the ship, the iceberg was out there and waiting. So anyways, then in a few years later, next wave turned into a pumpkin because IFC didn't want to wait for the back end, we were giving up to $100,000 to films and initially, we would get $100,000 advances. And so we can just turn the money around and make it available to someone else. So it turned into a pumpkin, late 2002. And then some people. And then I went around and talked to people about the state of distribution, because I'd been involved in finding distribution for all the films that we gave finishing phones to. And I found this new thing starting up this kind of alternative approach to distribution that was really exciting. And at the same time, a few people called me and said, you know, could I help them? figure out their distribution? And so I said, Okay, I'll try and then another person came, another person came in since then that was late 2002. I've, I've consulted on over 1500 movies. And the thing that's been lucky there is that I've been by the side of the these filmmakers, as they've been out on the frontiers. And so I can share the lessons they've learned good and bad, with other people I work with people I speak to or people that read my distribution bulletin. So it's, it's such an exciting time. Things are changing every 20 minutes, as you know. And so I, I wrote this piece called Welcome to the new world of distribution in 2008. Which, even though it's 11 years later, still, it's not only still true today, but it's more true than it ever was.

Alex Ferrari 19:08

It's still fairly revolutionary today, which is, which is shocking.

Peter Broderick 19:12

Right! Right! So I really, I really am excited about this idea of these new possibilities that are open to filmmakers the possibility of splitting a rights, the possibility of having more control of your distribution. I think that making a traditional all rights deal should be Plan C. I don't know what Plan B is, but Plan A is splitting your rights. And that's what I call hybrid distribution, which means it's not self distribution. You're working with different distributors to do, the things they're good at, and only the things they're good at not giving all rights to somebody where they don't care about some of the rights and the horrible at others and retaining the rights to do things yourself, which are going to make a big difference. So the combination of what they For you and what you can do on your own, the idea that you can have overall control of your distribution instead of, you know, giving all that control to a distributor is very exciting. And, and in this new world, I think every film needs a customized distribution strategy. Not not a formulaic approach, there was a couple years ago, I was invited to major Hollywood agency. And they asked me to talk to them about the future of distribution. And I walk in the room and I say, think of a spectrum of distribution from a formulaic on the one hand, where every film is distributed pretty much the same way to customize than the other where each film has its own strategy based on its goals, its core audiences. The room gets visibly upset in 10 seconds. I'm like, what's wrong? They go. We don't do customized. So I say, well, you don't need to customize just works better. They go, we don't do customized, we're not set up to do customized, we don't do kind of went downhill from there. But in their in their defense, they admitted they don't do customized. Whereas you look at the you know, major indie distributors now who kind of claim I mean, and there are examples. I mean, sometimes the flex, searchlight, you know, whatever, but mostly it's throw it against the wall and see if it sticks. If it sticks, the distributor will support it some more. If it doesn't stick, they're not going to give you the rights back. And they're not going to support it, either.

Alex Ferrari 21:37

Yeah, I mean, I mean, from my experience working in distribution for as many years as I have, as well, first in post production. And now with with indie film, hustle, I realized that nobody knows anything. First of all, that's that's very true. like nobody really understands anything in regards to distribution, because, like you said, it is changing every 20 minutes. What was true. Last year in T VOD, is no longer true this year, and vice versa. And then there's also brand new revenue streams coming in all the time or platforms, new situations, new options, like tug was never a thing before we could do on demand screenings. And remember when DVD was the Savior, and when VHS was the Savior and blu rays are the Savior now, t VOD used to be but now a VODs, turning into where a lot of the money is being made in the streaming world, like there's so many different things. You know, I find that this is the distribution, you know, infrastructure or the legacy model of distribution. These guys are built this system basically to to benefit themselves. And that's fine. They're a business. And that's what businesses do. But like you just said, perfect example is we got to customize, or we don't customize, they're completely closed off. And these kind of finite mentalities is where they're not going to make it in the long term. As blockbuster proved this Kodak proved, as so many companies that we've seen has proven case in case again, there are new little startups coming up that are shaking up things. I mean, there Netflix was a nobody. And they literally transformed the entire industry.

Peter Broderick 23:16

Well, it's interesting. The juxtaposition of my experience with Kodak and my experience with Netflix, a couple, I don't know, eight years ago, 10 years ago, I was doing a one on one discussion with Ted Saran dose at some festival somewhere. And so in the middle of the discussion, I asked him if he'd read a book called the innovators dilemma. And he looks at me like, as somebody be somebody from inside Netflix telling me because it turned out everybody at Netflix was reading that book. And thinking about how it applied to what Netflix his choices were going forward. And the book is about how a new entrant in an industry that's using newer technologies, challenges, you know, the company that's dominant, and what that company should do. Anyways, so obviously, at that point, they were still red envelopes. And but thinking digitally, and thank you forward. I think the challenge for a lot of indie distributors is that they're, they keep looking backwards. They keep looking for for that hit, again, that they had five years ago, but that that things have changed, and they're not looking. It's not just that they're not looking forwards. They're not even looking around at what's going on today. So they're losing opportunities. A great example of that is the film ketty the documentary it's about seven cats in Istanbul. Okay? So the filmmaker is Turkish she when she grew up, she had like 22 cats in her backyard and now she's living in LA and she said, gonna make a documentary about cats and Eskimo because they're like, they're not like there's not house cats and wild cats. They're just Cats and like in you know their sacred cows in India, they're in a host elevated status. So she goes to goes to stubble films The story of seven cats and then takes it to film festivals. Because she wasn't in Sundance. It didn't get seen there. Because the distributors that they show the movie to didn't have comps on cat movies. Seriously, no, no, I mean, it's, it's true. And also the reps wouldn't do it because they didn't have comps and cat movies either. So finally a Scylla scope calls Seattle, Seattle Film Festival and says what what movies broke out this year? And they said, Well, we had this movie about cats. And they stumbled, we did a screening and we had to do another screening. And they ended up doing for sold out screenings. And so sell scope, watch the movie and they said, Okay, let's let's do it. And they did a great job. The movie opened in New York the first weekend $41,000 in one theater, which is the most in one theater for any SL scope movie ever. And then it went on to make almost $3 million theatrically. And it was a situation where the fact that 86 million people are watching cat videos online, was completely lost distributors that had a chance to be involved with the movie. When I consulted on the distribution. And when I first met with filmmakers, I said, you're going to be fine. Once you get to digital distribution, you're going to be totally fine. It's gonna explode. And I don't I don't know what will happen with theatrical anyways. All those other companies missed that, that history of what was going on online. And so they passed on a movie, and they're so I think, you know, that's it. That's a case where you can't even see an opportunity in front of you because it doesn't fit your model. And, and what I almost I'm always surprised in terms of these companies. And there's various times like I remember one year, I was at the Toronto Film Festival, and I talked to a German distributor and I said to what new things are you doing? New, we're not doing anything new that we haven't done for 10 years. And I didn't know whether it was defensive, or he was like proud of the fact. But it was just weird to me. Because even if you were just doing your basic business, you could still be experimenting around the edges. And, and trying things out and the things that work you can do more of and the things that didn't work. Okay, you tried, you don't need to do those again. And so there's a there's a way in which it seems that you know, some people are hoping they can retire before they have to change anything.

Alex Ferrari 27:52

But isn't that the way in every industry though? Like, if you're if you're entrenched in the in the in the executive branches, you don't want to talk about something that's going to happen 20 years from now, you want to just know, but how about 20 minutes from now? because things are changing that fast?

Peter Broderick 28:05

And also, I mean, think about it, we had the music business example,right?

Alex Ferrari 28:09

And the book and the book business and the book business,

Peter Broderick 28:12

Right! But so it's like, it's not that hard to see that things are changing around you. And they're going to be in your industry soon. And even when they're starting to be in your industry, you just ignore them. So I think that what's exciting now is for the first time well for a while, you know, as with digital filmmaking, and no budget filmmaking filmmakers could decide to make a movie and make a movie, nobody could stop them. And now you can decide to do distribution and nobody can stop you and you can make your movie available globally. Now hopefully you can find partners who will do pieces of it. But you know, my, my view of global distribution for documentaries is that great get a sales company on board. And give them a year. And say for the first year will be good. And we won't sell the movie internationally to consumers. And then after a year, we're going to have the right to sell from our website into unsold territories. So if you sell 15 countries that leaves 170 countries or 180 countries where nobody has access to our movie, and we're going to be able to sell directly into them. And so now you're supplementing or complementing what they do, you're not getting in their way. So ultimately, you have you have not only access but a way, you know to reach those audiences. So the challenge is how do you market online, effectively, globally, and there are a number of filmmakers some of whom I'm working with who are figuring how to do that. So in some cases, they're not even relying on sales companies at all. They're selling directly so I think that you get into a situation where if you if you can find Great distribution partners great. But even without them, you know, for some combs that you can do extremely well.

Alex Ferrari 30:07

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. Don't you? Don't you agree that I mean, I've seen it 1000 times with filmmakers is that we're the only industry that will will spend a million dollars on a product and have no idea how they're going to get it to the marketplace. They just, they're just artists first, and they just put everything they have in it. And then when they walk into a distribution meeting, the distributor has all the power, they have no leverage whatsoever, because they're just like, well, I don't know what else to do. This guy, or this girl is telling me Oh, I'll be able to do this. And you're, and then the cops come out, I love the cops. The cops come out, I'm like, Oh, we estimate that your movie is going to make, you know, X amount here in this territory in that territory. But nobody really knows. And they just give they literally I call it a non tax deductible donation to these distributors, because Am I wrong? It basically that's what it is. Because you're giving them your movie away for 10 years, in hopes that one day you'll get a check. And let's not even get into, you know, the practices of these contracts, and what goes on behind the scenes and all that kind of stuff. But just on the on the first first part of that that statement? Do you find that most filmmakers just don't even think about distribution, let alone how they're going to get it to the marketplace?

Peter Broderick 31:29

Well, it's not only most filmmakers don't, but most companies don't either. So you know, major shadows, they they don't make, you could you know, I think you need a strategy, they don't have a strategy, they just have a plan that's like a formula that you use with the other five movies they just did. So you know what, what I say to filmmakers is the morning they think up the idea for their next film in the shower. That's what I want them to start thinking about core audiences and distribution. And there's so much they can do before they've made the movie while they're making the movie while they're in post production to identify those core audiences to reach out to them to build awareness, not to wait till you know the movies, so called done. So. But I think that, you know, studios are just, you know, they're in their own ruts. And this is how they do things, occasionally. And there's some examples with Fox Searchlight where they really were smart about how they'd figured out the core audiences. You know, Napoleon Dynamite is a great example. So they buy the movie at Sundance first feature, they come back to Los Angeles, and they sit around and they think about, okay, Who should we target, who's the core audience for the movie. So after some discussion, they decided to nerds. And their goal is to get every nerd in America to see the movie three times and memorize the dialogue. And so, the movie opens, the nerves are there. They're back. The second week, they're back the third week, in the fourth week, the nerds are there and their parents are showing up. So now you started with a core audience. You reach the core audience. It's how you keep your movie in theaters long enough that the audience can diversify from their branded Like Beckham is another example. So I figured out soccer moms, daughters and an Indian audience, they spread the word before the movie opens, they come out to keep the movie in long enough, and then it grows. My Big Fat Greek Wedding is an interesting example where first week you know Greek Americans were there the second week, first generation immigrants from all around the world, were there because they thought it was their story too. And so I think if people don't think I mean, the idea that Hollywood talks about audience still in quadrants, older males, younger males all, that is the most ridiculous aesthetic definition of audience

Alex Ferrari 33:57

at the 35 demographic, sir. Yeah, man, I'm like, Okay. Those days are those days are gone. There's in the world of geo targeting. And I mean, you could target down to the zip code, let alone interest lead. I mean, those days are so gone, but because they have all these financial resources and infrastructures in place, the machine can keep running for a little while longer until something else comes in. And that's something else at this point was Netflix or the whole concept of streaming, which I mean, how many when the Netflix start streaming, and when the Disney decide to jump in, you know, I mean, it's a decade a decade for them to that's how big of a shift that is for them to move. And I think they'll do well in their endeavor. They're one of the few I think they're one of the few they're actually going to do well. We could talk about the whole streaming wars thing because I find it fascinating on where we're, we're gonna go with this with this whole thing because Disney plus i think is going to do very well because they just have everything For that certain kind of audience, and then they're going to also include Fox, which was a great purchase, because now they have the adult version of Disney, Fox Searchlight, even if I think they're going to keep that going, I think they're keeping that going as well. But then you've got peacock. You know, I don't know how peacock is going to do with NBC Universal. Now, that's NBC Universal, peacock, Comcast, apple, you know, I there's just at a certain point, how many more subscriptions Can we buy? We can can we purchase?

Peter Broderick 35:30

Right? Right. So what do you think? Well, I think it's, you know, it's funny, because in terms of feature films, we're in this, the domination of franchises, and, you know, and studios. I wrote a piece that's on my website, called the truth about Hollywood, which is a review of this book. It's an amazing book. And basically, the idea that you make a franchise, you know, how much the last episode made and how much it cost? budget, it's not a question of how much the new one will cost, because, you know, and you probably have a pretty good idea of how much it's gonna make. And if 75% of the revenue is coming from overseas, and you know, those franchises are working in China, then why mess around with unique movies? Why mess around with lower budget movies, when you can just crank out this assembly line of stuff? So it's just interesting that then you see what's happened with cable and Netflix. And now now, the now that's where some creativity and risk taking is certainly not in, you know, feature films made by studios anymore. So I think it's, I think it's a, there's hope. But I want to make sure that, you know, that indie theaters can hang in there. Because I think I think that's an important part of the story. Although I think it's going to be more challenging. And this year was a pretty, pretty tough year.

Alex Ferrari 37:21

Yeah. And it's good. I mean, there's only so many books. I'm a huge fan of the blockbusters. I've, you know, I was, I mean, I remember the time when there were no superhero movies, and that went bad. That's why when Batman showed up in 89, everyone lost their mind. But now we're getting one a week, and they all cost $200 million. At a certain point. You know, it's going to start there's going to be it's going to be like the westerns, the westerns had a really great run, I think superheroes like Spielberg says, will eventually teeter off, I don't know when that will happen. It could be another 20 years. But there is such a hunger in the TV audiences, the TV shows that are coming out, you should prove it. There's a hunger for adult, well written entertainment, and independent film is that it can be that but there hasn't been they've been they've tried to create streaming services for it specifically, but I don't think that's the answer. Like I just I don't know what the I have an opinion of what the next step is, should be for filmmakers, like independent filmmakers, but there is an audience for it. And it is there's no reason why we can't be making money and make careers and building businesses around independent film. The ability for it is there the technology is there, the distribution is there. It's just kind of like somebody has all the parts to the Deathstar. But they haven't been able to put it all together yet or figure out how that puzzle goes. Would you agree?

Peter Broderick 38:49

I yes. And I think that once you expand the focus, not just from the US or North America, to kind of global view, and you think about aggregating audiences across national boundaries, then you don't have to have that many people in Argentina, connected and come to a movie, if you've got people in France, and you've got people in South Africa. So you know, a niche can become substantial, if you're able to do it globally. And so I think that the frontier is really thinking about international distribution and how we how independence can make that work, because right now, there's a few people out on that, you know, out in front, but there's definitely more opportunities to come and I also think that curation, which seems to be you know, completely underrated. You know, the thing about Netflix is that I know, at any moment, that there's some great films on Netflix that I will never hear of, they're there somewhere. I would love that. I would love it if I saw them, but I will never hear them. And that's it. Through on Amazon, and it's, you know, through a lot of places. So I think there's a way I think there's an opportunity for something that is more curated, but something that is focused on, you know, emerging independent filmmakers from around the world, where there's a kind of the people that, you know, are supporting that there's an element of kind of patronage or mentoring, wanting to make sure those people continue to have careers. I think there's exciting possibilities there. But the, you know, the major studios aren't going to aren't going to be interested when they can, you know, turn out another Avengers franchise, so. So I'm remain optimistic. I think that, you know, right now, for independent filmmakers, as you were saying before, there's more opportunities than there have ever been, doesn't mean, it's simple. But I think if they think about how they can build a personal audience, then that's the, that's the way to, you know, try to have a sustainable career. When, when I think about sustainability, and it's, that's I may sound like a boring word, but I did a webinar a couple years ago, called sink or swim, how to have a sustainable career as an independent. And it was one hour long, I did, it was my teammate, Keith quad, who why wasn't teamed up with them. And over 700 people came from around the world to this webinar, and it was amazing. And with my distribution bowl, and I have 12,000 subscribers, so I don't need the middle men or women, you know, like giving me permission to reach their audience. So I think that if we can, you know, think about how each each filmmaker can share, he can start to build an audience that they can take with them film the film, that's going to make a big difference.

Alex Ferrari 41:55

Yeah, and that's something I mean, I always tell people about niching down, I do believe that a lot of filmmakers will make these broad movies like I'm going to make a romantic comedy for a million dollars, it has no stars in it. And let's see what happens like that is such a, it's just a, that's like, I'm gonna hit a perfect home run. And even then it still might not be able to make money where I have always, I'm always telling people to niche to niche down to find an audience that's more controllable that you actually have the ability to target attract, keep that overhead, as low as humanly possible. So make make the movie for as little as you can, while still being able to create a minimal viable product for the marketplace and also realize your vision as an artist. So there's that balance that has to happen where a lot, I always tell people, I'm like, if someone gave me half a million dollars, I'd make 10 movies. Like I'll diversify my portfolio, you know, because there's much better chance of making money that way.

Peter Broderick 42:51

Well, I I totally agree. What I say is, what's the lowest budget you can make a movie well for? And, and if you if, say, the lowest budget is $2 million, well, don't make that movie next. I like that. That's fine. Just not next. I was in San Francisco, at a conference of you, I don't know, 10 years ago, and I ran into two women and they were going to make their for their first fixture, they're going to make this historical epic, of course, and I'm like, I've got bad news for you. Right now. And your point of your career there. There was not millions of dollars to finance a movie, anywhere in the world. So I recommend that you think about making a first film that's much more affordable. And they they listen politely. And I wonder why a year later, same hallway, same two women I run into. And I say So what happened? And they said, okay, we we made an ultra low budget feature, and we're in post. And I'm like, that is so great, because now they have an opportunity to launch their crew.

Alex Ferrari 44:03

Yeah, I love I mean, oh, yeah, all I this is my favorite comment. All all it all I need is 5 million at all. I just all I need is 5 million. But you've never made a movie. I know. I know. I know. But I've watched a lot of making of documentaries. And it's, it's amazing. We're the only industry that I know of that just watches somebody else do it and says to themselves, oh, I can do that. I could it's like you never see a real estate guy. someone's like, I'm gonna go build a house. I've never built one but I watched a lot of those shows on on home.

Peter Broderick 44:38

Yeah, I agree. I'm but the other part of it is okay. Beyond the question of how good a movie they can make is the question of how much control they'll have if they make it. So a $5 million movie, they're not going to have the creative control that they're going to have for $100,000 movie for sure. And in terms of distribution opportunities there they've narrowed them so much Where are you going to? How are you going to get 5 million back, you're going to have to give total control of your movie to somebody else. Whereas if it was $100,000, or $250,000, you could split your rights have control over distribution. And so people need to think about how they're going to retain control, or they're going to be sadly disappointed.

Alex Ferrari 45:19

I mean, it's it's the slow game versus the long game. It's the finite versus the infinite people are always looking at. You know, I find I call it the lottery ticket mentality where filmmakers are looking for these mythical stories. And like, I mean, if I hear Robert Rodriguez story one more time, I'm like, Dude, that was 30 years ago, at this point, he came out in 91. You know, so he's getting close to 30 years ago. And the stories of Kevin Smith and El Mariachi and these kind of lottery tickets were just like, amazing moments of time, where those guys happen to walk in at the right place at the right time with the right movie, we're nowadays and I was I was I had this disease for many years, where I thought the next movie was going to explode my career, I was going to get that million dollar deal. I was gonna win Sundance, I was gonna do all that filmmakers have this kind of mentality that they have to break through from where I believe that it is a how many movies Can I make in the next five years? How many? How am I going to build my career over the next 10 years, play that long game, as opposed to I need $5 million from my epic?

Peter Broderick 46:22

Well, also, I mean, I believe in slow distribution, like slow food. So I think that with a strategy, you start out with a strategy, you do the first stage of distribution, you learn from it, you modify what you do in the next stage, and you keep refining your strategy as you go based on the results. So you're going to learn what your assumptions are about those audiences, which audiences are showing up, which are, how you position the movie, is it working, and maximize awareness and each stage and ultimately, you look back on and say, we did the best we could instead of somebody else, you know, screwed it up for us. So I think that if people and there was a time, when filmmakers would come to me, and they say, I'm just, I'm just a filmmaker, I'm just a creative person. I don't want to do distribution.

Alex Ferrari 47:11

Now, there's not a time that's that time is today.

Peter Broderick 47:14

And I'm like, I'm sorry, you have to be meaningfully involved in your distribution. Even if you have distribution partners, you have to be involved, because that's how you're going to learn this this world and sitting back and going to a few panels. And the problem with sometimes As you've seen, I'm sure more experienced filmmakers, they have to unlearn what's no longer through. As opposed to people just starting out, got an open mind. Tell us what's going on. Okay, great. Now, we did it this way, and 95 seven, I'm like, and then here's another dimension that you may have run into. So let's see. This was probably, I don't know, maybe this was eight years ago, I did a series of events called distribution u, where it was just about the newest distribution opportunities. And the first one I did was a day long thing at USC. And afterwards, a nice woman came up to me and said, so I have a question I so yeah. She said, Would you do this for attorneys? So I say I'm one condition. She goes, What's that? She said that they want me to do it. Because they're also arrogant. Then, three months go by, I can say that says an attorney. Three months go by and she comes back sheepishly confounds me and says, I'm sorry that I couldn't have attorneys that wanted you to do it. So typically, now, because I, I seem, you know, I don't know, I've probably seen 3000 deals in these years. And so very, the norm is an attorney can make a great deal, a great 2013 deal for you. I'm like, Well, wait a minute. This is that six years ago, that's so fantastic. Things that you want aren't even in the deal and the things that you don't care about her in the deal, because the deals have changed and what's important, you know, but because they think they know what's going on. They're not like out there trying to figure out what what makes sense now. So I think filmmakers need to be really careful. do their due diligence, not just distributors, but attorneys, raps, whatever, and talk to other filmmakers who are currently or have recently been in business with these people. That's how they're gonna find the truth. And, and even the word even the worst bottom feeding distributor is good at one thing which is telling you what a good job they're going to do with your movie if they're good at nothing else. And and filmmakers, you know, have gotten no love for a long time and then somebody calls up and says, I'm Want to take him to the moon, you know, it's hard for them not to go,

Alex Ferrari 50:03

you're so pretty, you're so pretty. Once you come out, let's just go on at a date and we'll be fine. I promise you, it'll all be fine baby. It happens, it happens all the time. And you know what the funny thing is, I've noticed that it doesn't matter if it's a seasoned filmmaker, or if kid fresh out of film, school, they all fall for it. They all fall for it, because you could be a fantastic filmmaker, but you might not know anything about this side of the business. And that's how these predatory bottom feeder distribution companies, which there are plenty of take advantage of filmmakers. And it's, I mean, do you agree that I mean, I find that I was talking to a distributor the other day? And they said, Oh, yeah, you're the You were lucky, you got to check. Most guys don't even get checks. And that was, they didn't even see anything wrong with the statement that they just said, because it's an inherent issue in the entire side of distribution that like, Oh, it's just a given that you're going to get screwed. It's just a given that we're going to take advantage of you. And that's what I've seen. It's obviously wrong. It's obviously immoral. It's obviously a million things. But isn't that from your experience, seeing so many deals, so many of these kind of bottom feeder? They just, this is just inherent in the deals you get? I got Well, I got a deal the other day from a filmmaker I was consulting with, from a big distributor who will remain nameless, and he's one of these big indie one who proposed proposed that there are for the indie filmmaker, right? And I'm sure you know who I'm talking about 15 year deal with $100,000 market cap marketing cap for a $50,000 horror movie. They'll never see that he didn't sign it because I told them not to. That's ridiculous. But this is the kind of stuff they they throw out all the time. So I'd love to hear your, your thoughts on this?

Peter Broderick 51:52

Well, I mean, fortunately, because I've seen lots of deals. Seeing the experience, I always whenever I talk to new filmmakers, I'm always like, well, who distributed your last film? And how did that go? And you know, so I, I do know where the bodies are buried. Also, also, when I'm talking to distributors, I often find that I know more about what their competition is doing in terms of like, what's what's normal in the industry, so to speak. And then I love it, when they say, I'll say, Okay, I want to the filmmaker to retain the right to sell directly from her website digitally, and I'm on DVD, and they'll go, we've never done that before. And I say, that's great. This is an opportunity to try it. And if it doesn't work, you don't need to do it again. But if you don't try it, you're never going to know if there's an opportunity, you know, there for you. So, so I've been lucky because I just I know that it's not like they're going to say something to me that I'm going to believe that it isn't accurate. I mean, and often I can tell them stuff that they don't know about what's working and what's not working. And so, but I think that you have to be really, really careful, filmmakers should not be distributing for themselves and negotiating for themselves, as you know. And then if they're going to have somebody help them do that, it doesn't have to be a rapper, it doesn't have to be an attorney, it doesn't have to be a producer. But it should be somebody that really, you know, is living in the present. And, and doesn't have a conflict of interest, one of the problems and you know, this with the raps is that. Okay, so the rep takes out a movie, they may or may not work with this filmmaker ever again. But they have a great relationship with Sony classics. Sony classics, makes an offer. So the the rep wants there to be a deal. But they don't want to have be too adversarial with Sony classics, because they want to maintain the relationship with something classic, which is more important than maintaining the relationship with the filmmaker. So they're just it's a conflict. I mean, you should be able to use your good relationship with the distributor to get the you know, the best possible deal even if it feels a little uncomfortable for them, you know, instead of just Oh, yeah, it's like, the former life when I was a public defender, people would go to the prosecutors, and then they'd make a deal. And my attitude was, if if the prosecutor wasn't going to, you know, kind of be fair in the approach, I was just going to make their life a living nightmare with motions and, you know, conflict and so instead of, you know, instead of making that comfortable deal, you know, I had a way to fight for the clients by not, you know, just signing on the dotted line and I think that if people filmmakers or whoever there's negotiating for them says, Yeah, we're really interested in working with you, we just want to make a deal, that's fair. Now, nobody's gonna say I don't want to make a fair deal. And then I think instead of just taking the boilerplate, too seriously, you know, they could, whoever's tied to them can come in with a framework, oh, these are the rights that are available, is how we'd like to structure it. And then if they don't run away, or hang up the phone, then already they're there in your framework of what you want. So don't just be reactive, be proactive in terms of you know how that partnership could work. And obviously, you want a partnership, that's going to be good for the distributor, as well as good for you. You want a win win situation. But you don't want to, you know, a deal. That's, that's never, never going to work for you. And it's not just about money. I mean, obviously, money's, you know, at the center, but you also want something that's going to work well for your film and your opportunities to, you know, make more movies. And I think that it's so unfair for people to, you know, kind of throw a movie against the wall, they do a bad, bad marketing campaign. Yep, nobody comes out the first weekend, they give up, but they're not going to give the movie back to the filmmaker, because lightning might strike through no fault of their own, and it might be valuable someday. So now that you've got somebody got your rights for 710 infinity years, and, and you can't do anything about it, and the movies gone. So I think to think of a not a master slave relationship with a distributor, but a partnership, where you're doing things that are going to help the distribution, and they're making taken advantage of that set of thinking of you getting in the way, and they're doing the things they're good at.

Alex Ferrari 56:52

Yeah, and I mean, it's that whole non non taxable, non tax deductible donation mentality, unfortunately,

Peter Broderick 57:01

well, but if also, but if you're splitting your rights, then you're and you're only giving them the rights that they're good at, and you're keeping your other rights, and you can control your windows, then you really have a lot of control over distribution. And, but it can, it can really work for them as well. But you've

Alex Ferrari 57:20

also created a diversification of income streams, which is something that people don't understand was like, if you go with one distributor, and they don't pay you or go bankrupt, or something happens, you're done, where if you go with four, or five, six different distribution partners, and also self distribute, and also put it on your own website, you know, then like, I always negotiate with any of my films, I need to have it on my own streaming service, I need to have a control of it. So I can rent it, sell it, or use as part of my subscription, and you're gonna do, and you get the customer data, which you're not going to get any other way. Correct. So

Peter Broderick 57:55

and that customer data so invaluable. There's, there was a situation I was in New York, and there was a film I was wrapping and the This was the first time I'd run into a distributor saying they weren't going to give the filmmaker the right to make it available from her website digitally. So I'm walking down, I don't know, Third Avenue, wherever this company was nice. And I realized I'm in front of the building. So I'm going in the building, and I'm not leaving until I get this right for the filmmaker. So I went up there. And then I got everybody around a big conference table. And I explained, I said, This isn't just about money, this is about her opportunities to make more movies. And the only way she's going to get customer data is by selling directly. And, and I know you, you and I want her to be able to make more movies. And that's why it's really important. And they said, Okay, I mean, it wasn't just, oh, give us a piece of the pie, and you'll have less, you know, a smaller piece. So I think that it's so important for filmmakers to figure out a way to build, you know, relationships with the people in their audience that send them boring updates. But send them information they want to receive, be personal and passionate on the website, in the emails, whatever. So they, they, the people in the audience feel they're connecting with this human being that they really want to, you know, nurture and support. I think a lot it's possible when you take that approach.

Alex Ferrari 59:22

Now, before we go I wanted to kind of dive in a little bit to this whole distributor debacle which is what brought us together in the first place. Tell me your thoughts on disturber you first of all, you did write this amazing article. unbeknownst to me, I found it I think it came up on my radar. And then I reached out to you I'm like I gotta I gotta publish this on the on indie film hustle because it's it was wonderfully written really great information on there. And then you put it in the Facebook group I started protect yourself from disturber and people started looking like Okay, so what is first of all your Whole take on distributor and I'll ask you a few questions in regards to that article.

Peter Broderick 1:00:04

Well, I've known distributor from day one. And for years and years and years, I think they did a good job. And my, my sense of what's happened is there was like, major, major mismanagement internally, in the last 12 months, were distributor thought they had the cash flow, to continue to pay people, you know what they were owed, and then just guess, ran into this stark reality that the money wasn't there. And their margins were so low, that they were never going to catch up.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:45

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. But did they take but did they take? So basically, what happened was that they took money that was residual money that was coming into the bank account and using it to keep the company afloat and hoping that other money would come in? Because they were

Peter Broderick 1:01:08

they were paying filmmakers to I mean, it wasn't like they stopped paying all filmmakers. You know, I think that at a certain point. They just realized that they were in an impossible situation. And that and that, and that at that point, then I don't know how they decided on the ABC process or the bankruptcy process. They stopped communicating with filmmakers. And so, people were in the dark. I mean, I, I know, I have a lot of clients. And I know you had you were early on the, in the, you know, alert system. I was the one that held it. I watched, I watched her that that first podcast, and but so many people, even though you've done a couple podcasts, you know, anyway, written an article variety written article comark, as we get in touch with me who had no idea? No, of course, if you have happened, they were living in igloos. Pluto, I don't know. And so what I wanted to do, because some of the stuff on the Facebook side wasn't wasn't accurate. I mean, the idea that you have to have your film taken down first is not true. And I understand why people thought that. But then when you realize that Netflix agreed to not require that until just shift the pay to the filmmaker, then, you know, that's what we should be pushing iTunes and Amazon and other people to do. Absolutely. And now, in some cases, it won't work. And then you get into the taking it down and finding another aggregator situation, but so I just got so, you know, fairly self protective. filmmakers who were in this situation had no clue. Then I said, Okay, well, I'm going to figure out what the steps are. And it you know, so the, obviously, the first step is to terminate, officially terminate, you know, your agreement. And that's as easy as just sending an email to distributor saying you're terminated because under the distributor contract, if they go into an IBC process, then you can do termination, you know, immediately. So first step is to terminate, then, you know, I looked into what to do about the platforms. And basically, if you go to a platform, if you say, that's the term, I just sent this out yesterday that some filmmakers, copyright, is it the copyright? Yeah, if you say that copyright infringement is happening, then they pay attention. And there's a way to get them in each. Each place has a department that deals with stuff, attorneys and whatever. And then you can, even though, you know, the classrooms don't want to deal with individual filmmakers. In this case, it seems to me because so many filmmakers are involved and have been affected by distributor, they should make an exception and just, you know, develop a kind of blanket policy where they could say, Okay, we'll just make you the pay. And you know, that'll be it. With glass Radner that's running the NBC. And real quick, can

Alex Ferrari 1:04:27

you explain what an ABC is and why they didn't file bankruptcy because I think a lot of people don't understand what that is.

Peter Broderick 1:04:33

So ABC stands for assignment for the benefit of creditors, which, if you were a creditor, that would sound good, but in fact, in an ABC situation, it's it's a lot looser, less transparent than in a bankruptcy situation. And one thing we know is the company doing the ABC will get paid, obviously, which is lower

Alex Ferrari 1:04:59

Which is less Ratner,

Peter Broderick 1:05:01

right? Yeah. And their lawyers will get paid. And then next one that what will happen is the secured creditors will get paid. And then, and the filmmakers are obviously unsecured creditors, so they're going to be last in line and they'll get pennies on the dollar if that. If that right. So I think that there's an advantage to an ABC. From the standpoint of a company that doesn't, you know, want to go through the strict process, it gives them a little more flexibility. I mean, I still don't understand why. To my knowledge class Radnor has gotten in touch with no filmmaker

Alex Ferrari 1:05:40

glass Ratner to my understanding glass Ratner has Well no, as of as of a couple days ago, everyone got this letter from GD ABC LLC.

Peter Broderick 1:05:51

Okay, well, they're not not the filmmakers that I'm involved with got that letter.

Alex Ferrari 1:05:56

Yeah, this is starting to come out. And if you go on the group, the group is actually starting to post I got the letter, I got the letter. And here's a link. So this is the only official communication to everybody in this, this debacle is this letter, which is absolute BS. And it just when we looked at it, you're like, it's gonna take nine to 12 months. But what I love about this letter is like how much was in the end, it says here, nine to 12 months, the ABC is expected to be a nine to 12 month process before any distributions or funds are made. That means that means all the attorneys have to get paid first, then my favorite part is the amount and type of claim, can you tell us how much we owe you? Well, we can't because you haven't given us the reporting on the back end residuals that you owe us. So how can we you know what I mean? It's, it's, it's this is basically they're just walking through the process for legal purposes. But this actually means nothing to actually filmmakers getting their film, money that they're owed back, let alone money that they basically stole for service unrendered for like myself, where I invest I put in for a client, I put to them for films, and it cost me $4,000, to submit it to the platforms. And that's how I was going to do it. I had to call my credit card company up and get it refunded by the creditor. Yeah, yeah. And that's what we started putting it out to people on paypal at six months. In credit cards, it's 90 days. But if you if you reach out, and if it's a little bit farther than that, you can go look, these guys are the defunct company, there's fraud involved. They did, they took my money, and they said that they didn't do anything. There's other ways of getting your money back. But if you go back farther than that, it's a little bit more difficult. But I was able to get my money back. Thank God. I know a lot of other filmmakers have been able to as well.

Peter Broderick 1:07:41

Right. Well, the other issue is, I think that in the Netflix situation, basically, distributor had a process where they would release the rights back to the filmmaker in a kind of simple way. I don't know, I don't know exactly what it was. But there was a policy. But I don't think that that happened for Hulu or some of these other places. So then. So then, if you go to platforms directly, and they asked you so what's your ID number? What's your account number? Good question. I've no idea what the distributor account number is.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:28

It's a nightmare. It's your it's a pure nightmare, also, but from what I understand, from filmmakers I'm working with only the only company that has come to the plate to try to fix this is Netflix. Netflix is quietly reaching out to individual producers and filmmakers who had deals with them, you know, buy out, you know, as far as, you know, licensing deals, and are doing something in regards to making it right. So if they're owed another $200,000 off their deal and distribute got that money and never paid it to them, they're slowly going to start creating ways of them to make sure that they get their money, because I feel that they're doing it very quietly, by the way, because Netflix doesn't want the bad press. The other guys haven't even caught on to this yet. But I think someone in the legal department probably said Hey, guys, so you're saying you're saying Alex that Netflix is going to try to make up any monies that

Peter Broderick 1:09:26

any monies that were saying to the stripper that Wow, that's amazing.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:29

And also change it over to a direct you know, pay direct. But the thing is, is and I want to ask you this, Peter, because this I think is something that one of the distributors and one of the most vocal people on the on the platform brought up originally was on Joe Dane on on the the, the Facebook group was this a stripper thing is just a very simple symptom of a much larger problem, which is the entire system of Philippine immigration and how it runs where The the platform's have forced film aggregators, or film, excuse me, forced producers and studios, all of them, including the big boys to run through these five companies. On a technical standpoint, I completely understand it's like going to a post house, completely get it. But the problem is that they also forced them to deal with the money without any regulation without any fiduciary responsibility, without any sort of oversight on millions and millions of dollars distributed. Rob was running hot, not to hundreds, but probably 10s of millions of dollars of residuals probably ran through that company a year based off because they were they were one of Netflix's preferred vendors. Exactly. So how is that make any logical sense? And then also, on the on a legal standpoint, I'd love to hear from an attorney. Are the platforms somewhat liable for forcing us to go through these companies? I mean, to do business.

Peter Broderick 1:10:57

Okay, well, let's go back to steps. Okay. Another another question, which I think is an important question is, is aggregation a sustainable business? And I would say that, if you have if it's possible, another business, so let's say,

Alex Ferrari 1:11:17

from your digital, there are post outs or bitmax.

Peter Broderick 1:11:20

Yes, right. Right. So in that situation, as long as they're not having to deal, they can kind of automate the process, and they're not having to spend a lot of time dealing with individual filmmakers, you know, maybe it's a breakeven situation, or they can make a little bit of money. But when people look for another aggregator, now, I'd listed in the, in the distribution, building the qualities that they should be looking for, and one of them is to, you know, get help if they needed from a human being. And and that's not, that's really not an option for most of these places. Because they don't want to have the personnel to have to deal with filmmakers when they you know, something goes wrong. So as to the question of, do the platform's have any responsibility? I don't, I don't, I think what? I don't know the answer. And I certainly don't know, I'm not an entertainment attorney. So I have no clue if there's some, you know, some way that that could work. Because I think what they'll say is, well, we didn't make you go through this aggregator.

Alex Ferrari 1:12:34

You make us go through all aggregator sites, only five of them?

Peter Broderick 1:12:38

Well, there's, I think there's actually more now, okay, we could go over that at some point. But we didn't make it go through this aggregator you chose to go through this I read or now In fact, it's interesting with distribute was preferred, right, Netflix for Netflix. And then what happened was, the Netflix filmmakers started not getting money. Then they went back to Netflix, and they said, Hey, what's going on here, and then that Netflix stepped up, and then they actually did something proactively. The other folks I think, are just, you know, down in their foxholes, hoping that they don't have to do anything about it, aside from the money. I mean, they just don't want to do they don't want to try this sorted out and,

Alex Ferrari 1:13:23

and then and then guys like myself, and you are still making a stink out of this and, and creating more. Look, if I hadn't released this info. If I didn't done that podcast, people would probably still be in the dark and it still be information would be kind of loose all over the place. Yeah, no, that's true. And you know, so it was it was us launching this information and this initiative to get information out there for the filmmaker, that we even know what any of this it's it's, it's still disgusting how this company is run this whole. There's to put it, this could have been a very easily dealt with situation like guys, something that like a public announcement, hey, when something went wrong, we mismanaged our thing. This is what we're gonna do. This is how we're going to take care of you guys. It's just simple stuff. Man. That's simple stuff. It doesn't have to be. But there's still even to this day still have not made a public announcement class, Ratner's only cares about themselves, because they want to get paid. So it's, it's, it's fascinating how that how this company is going. But I do think that this is a symptom of a much larger problem, you know, and is this a sustainable business model? And our and I always tell filmmakers, as well, is your film a good candidate for self distribution and going through an aggregator? Because if you can't recoup the money that you're spending to get these films up on the platforms through the platforms, and there's no good ROI there. Why would you do something like that? then figure out other revenue streams or figure the other partners?

Peter Broderick 1:14:47

Yeah, but I think that's complicated because it is it's it's not just revenue, it's being on a platform. So when distributors started out, what was distinguished distributor from anybody else was they could guarantee That you would be on iTunes, and nobody else could do that. So, you know, being on iTunes was something that people valued aside from the money just, it's like legitimation.

Alex Ferrari 1:15:12

It's a vanity, it's a vanity platform in many

Peter Broderick 1:15:14

ways, not just vanity. But I mean, I think that in terms of filmmakers careers, you know, they can say, you know, my film was at that point being on iTunes was, you know, a big deal. So, I think that I think that the idea of having an alternative, where you can choose a traditional aggregator where they're going to take 25%, and do not much more than this trimmer did. And then at one point, distributor was also pitching a subset of their films to Netflix, and who and places like that they weren't charging to do that. And then if they got, if they made a deal, then they would get, they would get some money, but not a percentage, they would just get some fee, I think then later in the charge for it, and well, I think later, what they did was they said, Okay, we'll pitch it to Netflix, if you agree to give us 15% of the thing goes through. So I think there was a shift.

Alex Ferrari 1:16:13

But also, I sold one of my first feature I sold to Hulu through them. And the deal was that I had to pay to get the movie pitched. If they don't get the movie, if they don't accept the movie, then I get a percentage of that fee back. But also there's a 10% cut off of the off of those deals to Netflix and distributor, and Netflix and Hulu. So that was it. But it was constantly shifting at the very end, they were charging $20 for you to get a check. I mean, literally. Yeah, I

Peter Broderick 1:16:45

think that once, once the they were on the downhill slide, then they they just kind of tried to grab different methods and hoping against hope that they could make it work. But I one thing I do think, though I don't think there was fraud, I don't think there was intentional, I really believe that it was just gross mismanagement. Because I know that you know, who ran distribute changed over the years, but at least in my experience with a lot of filmmakers who have worked with a distributor, I felt compared with other folks out there. And this includes distributors, I think that they were behaving, you know, ethically and that cooking the books or whatever. And I think that one of the problems with the dashboard was that it wasn't so much that it was and I'm sure that at some point, it got totally out of whack, but they weren't getting good information back from the platforms, either. So it was a challenge where, you know, Amazon didn't send them a report, even though there had been money and you know, whatever. So I think the idea of it, the dashboard was great, but I think that in the execution, it was it was problematic. So anyways, I think that there are steps that everybody can take, I'm glad that he got a letter saying that nine to 12 months until any monies paid. I mean, that's amazing. And I one of my questions would be is glass reading or getting paid monthly?

Alex Ferrari 1:18:21

Of course they are.

Peter Broderick 1:18:24

No, but they might have a flat fee. They might have a flat fee if they have a flat fee. But if they're getting paid monthly then to say nine to 12 months is just

Alex Ferrari 1:18:31

they're milking the cow. They're milking the cow as long as they can. Yeah, yeah. Yeah, I gotta I gotta reach back out to Seth, I got to talk to him that glass renders what the deal is after this, because it's it's pretty insane. Also, you know, I don't know if you know this or not, but the LA Times is doing a very deep investigative report on this. It's very deep, and they've they're going in deeper than any of the other. Other reporting has been done. And they're going places that I can't, because I don't have the resources. Nor the nor nor the legal department here at indie film hustle. Right? They're going to be two. So that's coming out, hopefully in the next week or two. So I've been talking to them heavily as well. So it's it's it's this is an ongoing on story. This is kind of the first of its kind. There hasn't been a film aggregator that's gone down. There's been distributors have gone down, but they've never been aggregators have gone down. So this is a very interesting and unfortunate situation.

Peter Broderick 1:19:35