LITTLE ODESSA (1994)

Outside of independent film circles, director James Gray isn’t well-known. His filmography mostly flies under the radar of the larger moviegoing public, but what little output he does have is almost always well-received by critics. As a storyteller, Gray specializes in stark chamber dramas with Shakespearean levels of familial conflict– not exactly fodder for the 3D blockbuster set. However, give the man a little bit of your time, and you too will realize that Gray’s uncompromising vision is poised to one day deliver him into the pantheon of great American directors.

I feel a deep kinship with Gray in that we both are largely influenced by cinema of the 1970’s– that bastion of compelling drama and character-driven storytelling. When I envision myself making a drama, it usually looks a lot Gray’s austere work. Naturally, I respond to the man’s films on an aspirational and intangibly visceral level.

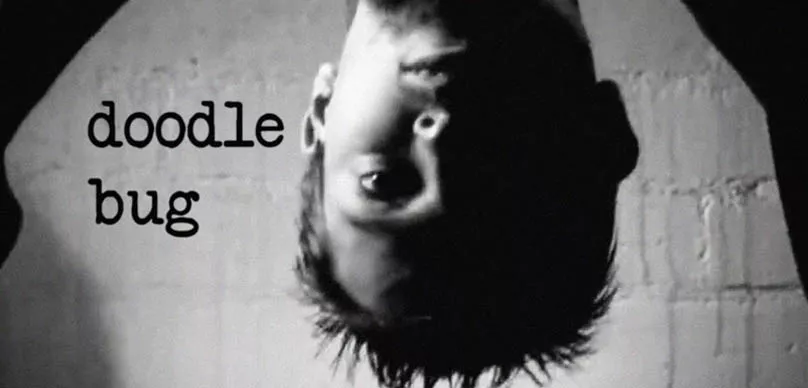

Gray hails from The Bronx, and the subject matter of his films hasn’t strayed too far from that general sphere of influence. He was inspired to become a filmmaker after viewing the works of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, two directors whose touch can still be felt in Gray’s recent work. He learned his craft in the venerable halls of USC’s School of Cinema-Television, cutting his teeth on two shorts- 1990’s TERRITORIO and 1991’s COWBOYS AND ANGELS. The strength of the latter landed him an agent right out of school, and catapulted him directly into the making of his first feature, LITTLE ODESSA (1994).

Because neither TERRITORIO or COWBOYS AND ANGELS are (to my knowledge) publicly available, I’ll start the dissection of Gray’s ouevre with LITTLE ODESSA. The film is set during the cold winter months in New York City’s Brighton Beach neighborhood, populated predominantly by Russian immigrants. Joshua Shapira (Tim Roth), a calculating hitman, takes on a job that brings him back to the neighborhood he grew up, near the family he hasn’t talked to in years.

When his younger brother Reuben (Edward Furlong) seeks him out to share the news that their mother Irina (Vanessa Redgrave) is dying, Joshua is forced to reconcile with his estranged family and potentially compromise his operations. Inevitably, his return will have tragic and devastating consequences for all those caught in the wake.

At first glance, one would never know this was Gray’s first film, and that he was only twenty five at the time of its production. The performances are incredibly accomplished and heartfelt. Roth doesn’t get to headline a film very often, but he makes the most of it here by turning in a chilling, focused performance as a contract killer in the process of an emotional breakdown.

He embraces the greasy sleaze that the role requires, but also finds the humanity and the empathy within those fortified walls. As the younger brother Reuben, Furlong builds on the promise seen in his debut, James Cameron’sTERMINATOR 2: JUDGEMENT DAY (1991). Furlong belongs in that specialized sect of actors, populated by the ghosts of James Dean, Brad Renfro, and River Phoenix, who would command striking, powerful performances early in their careers before succumbing to vice and personal demons stemming from their success.

Whereas Furlong isn’t exactly dead yet, he’s arguably squandered his potential by dabbling in hard drugs and straight-to-video shlock. But in LITTLE ODESSA, Furlong bubbles with a focused intensity and angst. The story really belongs to the family dynamics of these two brothers, and the consequences of Joshua and Reuben’s life choices make for incredibly compelling tragedy.

The supporting cast is comprised of lesser-known faces, but they make no less an impact. Vanessa Redgrave, as the brothers’ sickly mother, is a stark reminder of the frailty of life and the inevitability of death. She is a source of strength for her boys, but as her health rapidly worsens, so do the prospects for a bright future for Joshua and Reuben.

Maximilian Schell plays Arkady, the tired patriarch and embodiment of the Shapira clan’s cultural heritage. An Eastern European sensibility runs through all of Gray’s work, and Arkady is perhaps the first concrete example of that influence within his filmography.

Gray partners with Director of Photography Tom Richmond to create a lived-in, worn-out look that suits the subject matter and the setting. Shot on 35mm film and presented in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, LITTLE ODESSA is a gorgeous-looking work. Richmond and Gray create an image that’s high in contrast, with an even color scheme that deals in a predominantly black and brown palette.

The 70’s cinema of Scorsese and Coppola (especially 1972’s THE GODFATHER) are a huge formative influence on Gray, and it’s evident that he tries to replicate that sepia-tinged look in his own body of work. He adopts a classical, minimalist approach to his framing and pacing, yet he subtly redefines it for the contemporary era. No shot is frivolous or wasted. Each frame is carefully considered.

Grey often composes shots using tangible framing elements like doorways or windows. The effect, while somewhat distancing, has the effect of voyeurism; it’s as if we are ghosts drifting through the walls of tiny tenement houses and bearing witness to incredibly private family conflicts. Gray supplements this effect with a variety of considered camerawork, mostly comprised of traditionally locked-off tripod shots as well as dolly movements. He also incorporates handheld camerawork, albeit sparingly, as a strategic tool that modernizes the aesthetic of his classical forefathers.

Gray also creates a realistic sonic landscape to match and augment his visual work. While the credits list a collaboration with Dana Sano for the film’s music, Gray largely eschews the use of score throughout the film. This allows the story developments to resonate without music emotionally manipulating the audience. However, Gray does use a variety of circa-90’s source music to establish his setting and timeframe.

The most powerful musical elements of the film, however, are when he uses operatic choral music to underscore the tragic elements of his gritty family drama. Much like the use of similar music in THE GODFATHER, the style of music communicates a rich cultural lineage stemming from The Old World that fits the film’s deeper themes.

As a debut work, Gray shows a considerable amount of confidence. It’s even more stunning when you consider that he created a film as accomplished as LITTLE ODESSA at the age when most other guys are still doing keg stands during Homecoming Week parties at their old fraternities. His filmmaking career starts with a bang— quite literally, as the first scene is Roth crossing the street to shoot a guy sitting on a park bench, point blank in the head.

More importantly, however, is that LITTLE ODESSA begins a career-long exploration of the modern immigrant experience in America; more specifically, that of the Russian and Eastern European background. Theirs is a rich heritage full of deep-seated religious beliefs, customs, and rituals.

Gray is interested in exploring how these Old World cultures assimilate into the melting pot of the New. It’s important that the action takes place in the outer boroughs of NYC. Gray’s characters are outsiders, doomed to the fringes of civilization and only able to look upon the glittering skyscrapers of Manhattan (itself an embodiment of the American Dream) from afar.

Another aspect of Gray’s work worth mentioning, and already apparent in his first work, is the theatrical nature of his stories. Unlike Sam Mendes, whose craft is influence by a seasoned career in directing for the stage, Gray’s character dramas more closely resemble Greek tragedy in their exploration of inter-familial conflict.

However, I also see a secondary, less-mentioned influence in Gray’s work– that of the Shadow Plays from the Far East. Gray makes compelling and artful use of shadows and silhouettes throughout his work as a storytelling tool, and as a way to inject expressionism into his otherwise starkly realistic narratives. Cinema itself finds its roots in the Shadow Play tradition, (objects projected onto canvas via light), so it’s fitting that a cinema purist like Gray incorporates it into his aesthetic.

In the eighteen years since its release, LITTLE ODESSA has drifted into relative obscurity. I only saw the film for the first time a few days ago, but I imagine that it’s still as potent and relevant as the day it was released. There’s a hustle, a deep urgency, at play here– not just for the immigrant characters of Gray’s story, but for Gray himself, in an energetic bid to play in the Big Leagues.

It’s not a perfect film– indeed, I caught many beginner mistakes (like a microphone dropping into the shot)– but it is a powerful and highly-overlooked experience. LITTLE ODESSA, for one, is a reminder that Furlong was (and still could be) a truly great actor. However, he’s only one small part of a much more intricate narrative. I suspect that once Gray gains more recognition from the cinephiles of the world, they’ll look to LITTLE ODESSA as the first important work of a major American storyteller. Here’s to hoping that, one day, Criterion comes calling and gives it the treatment it deserves.

THE YARDS (1999)

As an independent filmmaker, the hardest part about making a film is raising the money. Studios have the luxury of hundreds of millions of dollars to funnel into their development slate, while most independents have to beg, borrow, and steal for meager budgets. In the days before digital democratized the medium and dramatically lowered the cost barrier, most of these indie mavericks would go years between projects. As a staunch advocate for traditional celluloid acquisition, James Gray is certainly no exception to this phenomenon.

It was a full five years after the release of his debut feature, LITTLE ODESSA (1994) until he was able to channel its successes into the making of his follow-up. That film, 1999’s THE YARDS, was a dramatic upscaling of Gray’s vision and scope and enjoyed the participation of an eclectic, dedicated cast of famous faces. With his second feature, Gray continues to bring his all to every effort, and delivers a riveting tale of bureaucratic corruption and conflicted loyalties.

Leo Handler (Mark Wahlberg) is a small-time crook, recently released from a stint in jail for stealing a couple cars. He may be a tough guy on the outside, but he’s got a heart of gold. When he returns to his small family in Queens, he’s given a new lease on life in the form of working for his Uncle Frank (James Caan), a fiercely competitive contractor for New York’s subway transit authority. Dismayed at the time and cost it would take to go to mechanic’s school before he would begin working,

Leo begins shadowing his cousin and Frank’s sales executive, Willie Guiterrez (Joaquin Phoenix). Before he knows it, Leo finds himself deep in Willie’s world of shady back-room deals and nocturnal sabotage raids on rival firm’s trains. When a routine raid goes awry and ends in the death of a yard operator and the maiming of a police officer, Leo is pinned for a crime he didn’t commit and must clear his name– even if it means betraying his own family.

THE YARDS is an intriguing story that deals heavily in Gray’s thematic preoccupations. Based off the strength of his script (which he co-wrote with Matt Reeves of CLOVERFIELD fame) and LITTLE ODESSA’s success, Gray was able to assemble a truly fantastic cast. It also helped that the infamous Hollywood producing powerhouses, The Weinstein brothers, threw their significant amount of clout around to get the film made.

Fresh off his career-making performance in P.T. Anderson’s BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997), Wahlberg continues to shed his cheesy “Marky-Mark” persona and deliver a powerful, understated performance. His peach-fuzz-goatee’d ex-con projects a quiet intensity, expressed primarily through low-volume mumbles and keen observation. He evokes a considerable amount of sympathy for his character as a guy who’s just trying to do the right thing, but can’t help but get drawn into trouble by those closest to him.

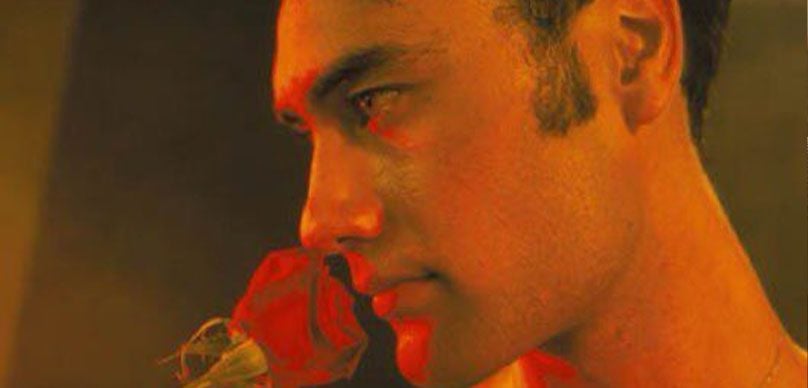

Conversely, Joaquin Phoenix is a broiling, brooding presence in one of his best early-career roles. A year later, he would gain worldwide recognition for his villainous turn in Ridley Scott’s GLADIATOR (2000), but his antagonist here is much more complex and interesting. His Willie Gutierrez is a slick, oily devil in a suit who’s proud of his sales prowess and even prouder of his criminal cunning.

When his actions kickstart a chain reaction of trouble, his true character comes out– that of a desperate coward who will do anything to cover his ass, even if it means betraying his own family. THE YARDS is Gray’s first collaboration with Phoenix, which has since blossomed into one of the tightest director/actor duos since Martin Scorsese and Robert DeNiro (or Leonardo DiCaprio for that matter).

James Caan, who lately seems big into appearing in the early works of directors (see Michael Mann’s THIEF (1981) and Wes Anderson’s BOTTLE ROCKET (1996)), gives a layered, nuanced performance as Frank, the king of his own subway mini-empire. It reminded me a bit of Paul Newman’s burdened anti-hero in Sam Mendes’ ROAD TO PERDITION (2002) in that he’s an honorable crook whose strength stems from his family and his status as patriarch. However, he’s not afraid to do what has to be done, especially when it comes to ensuring the survival of his business.

With his dignified mustache and burly, tough guy mentality, Caan projects an authentically East-Coastal, lived-in aura.

Despite fashioning his stories in a primarily male-oriented setting, Gray shows considerable perception when it comes to sketching out his female characters, aided by an incredible eye for casting. Charlize Theron, in her short black hair and thick eyeliner, completely disappears into her role as Erica, the woman at the center of a love triangle involving Leo and Willie.

She’s as tough and gritty as the guys, but doesn’t lose her inherent femininity in the process. As Leo’s mother, Ellen Burstyn turns in a powerful performance as a woman broken-hearted by her son’s descent into crime. It’s not the usual stock character, however– she’s quiet, yet firm in her convictions, which makes her arc so compelling. Her reaction to first seeing Leo after the media has tagged him as a potential cop killer– covering her face in shame and turning away to sob— is one of the most arresting moments of the film, and shows why Burstyn is quite simply one of the best.

Rounding out the rest of the female characters is Faye Dunaway as Kitty, Frank’s strong-willed wife. I didn’t recognized her at first, as I’m not used to seeing Dunaway as an older woman in thick glasses, but she gradually reveals herself to be a significant character in her own right– just as powerful and influential in matters of the family as her husband is.

Throughout all his films, Gray has cultivated a very distinct aesthetic, which solidified into its current incarnation beginning with THE YARDS. The luxury of a higher budget allowed Gray to pour a significant amount of resources into the look of the film. Collaborating for the first time with the legendary, late Director of Photography Harris Savides (rest in peace, big guy), Gray substantially upgrades his style.

Shot on 35mm film in the 2.35:1 anamorphic aspect ratio, Gray and Savides create a gritty, autumnal look that’s quite beautiful. Savides’ signature naturalistic lighting gives the image a high contrast and even colors that draw from Gray’s preferred black/brown palette. Indeed, the entire picture seems to bathe in a faint sepia tone that suggests a worn-out photograph.

Gray is also one of those rare directors who uses his visual style as a way to wordlessly convey deeper truths and subtext. And not just in his camera movements (which are a strategic mix of static, dolly and slow zoom shots), but in his framing and lighting. I’ve written before about Gray’s tendency to compose shots through a framing device such as a doorway or a window, but THE YARDS is the first instance where I became aware of why he chose to shoot in that way.

I previously made the observation that Gray’s plots hinge on a strong family dynamic that’s firmly ensconced in the rituals and customs of its European heritage. Because of the insular nature of these relationships, Gray invites us to become passive observers, and not active participants. By composing shots as if the audience is physically distanced and/or blocked from the characters, and suggesting that the characters don’t know they’re being observed, Gray creates an intimate, breathless story that holds us at arm’s length.

It’s not a cold distance (like the work of David Fincher) but a warm one that engages us in the story while simultaneously suggesting that we’ll never truly be a part of their world. That’s why a cathartic, brutal slugfest between Leo and Willie is staged from a distance, in long un-broken takes– you’re not a part of their circle, so you don’t get to step into the ring with them.

Another visual component that Gray uses to a subtly rich effect is shadow. Gray’s shadows are deep and inky, almost like a void. The color black is just the absence of light (and by extension: of truth), an idea that informs Gray’s placement of shadow in the frame. Silhouettes and backlit figures suddenly take on exaggerated, poetic meaning in an aesthetic that’s spare in its stylings.

About three quarters of the way through the film, there’s a scene where Willie comes knocking on Erica’s door and tries to falsely persuade her that he’s not the one who’s responsible for the train yard killings. When it came to lighting the scene, Gray and Savides set up an overhead key light that throws Phoenix’s eyes into deep shadow.

Because Erica (and the audience) can’t see any semblance of truth coming from the blackness where his eyes should be, his over-articulated claims of innocence ring false. Our eyes are windows into our souls by which we’re able to discern truth, so obscuring the eye likewise suggests an obscuring of truth. It’s an incredibly subtle and effective technique, and one that I expect Gray to continue using.

Gray also teams up with Howard Shore to create a subdued, yet rich score that fits the film. Comprised primarily of strings and ambient tones (with a little oboe or clarinet thrown in), the music appropriately conveys the stakes and gives the film a distinct New York flavor.

THE YARDS shows considerable growth for Gray as a filmmaker. The film retains some earlier directorial stylings fromLITTLE ODESSA (all lower-case titles and a gritty outer-borough NYC setting), but also expands the scope of his story to focus not just on familial conflict, but on bureaucratic corruption and its subsequent social unrest. Gray paints his characters like subway system mafiosos in the many scenes of back-room dealings and favor-cutting with police.

Very little about the film rings false, save for some exposition-heavy dialogue in the film’s beginning. THE YARDS is a powerful morality tale about having to choose between allegiance to family or to justice, a conundrum brought about by a single operating principle: “don’t be a fucking snitch”. It’s a compelling crime drama that hasn’t aged a day in the nearly twelve years since its release. Just like LITTLE ODESSA before it, THE YARDS deserves at least a closer look, if not a full re-appraisal of its place within cinema– not as a bargain-bin gangster film, but as a modern classic.

WE OWN THE NIGHT (2007)

In 2007, director James Gray released his third feature film, WE OWN THE NIGHT. It was the first film of his that I had ever seen, and I distinctly remember the vintage-inspired theatrical poster. At the time, I thought it was one of the coolest posters I had ever seen, let alone the coolest title I had ever heard of. When I finally got around to watching the film, I confess that it wasn’t as exciting as I had built it up to be in my mind.

In examining Gray’s filmography for the purposes of the Directors Series, I was interested to see how my own personal growth as well as a wider exposure to cinema would inform a second viewing five years on. While it’s certainly Gray’s most ambitious, sprawling effort to date, it has its fair share of flaws. Ultimately, however, it holds up much better than I remembered.

The year is 1988, and the drug trade is a well-known presence on the gritty streets of Brooklyn. WE OWN THE NIGHTcenters on the Grusinsky family, a respected immigrant family with a rich lineage in law enforcement. There’s the patriarch, Burt (Robert Duvall), a tough old bastard with an unwavering commitment to the law. Following in his father’s footsteps is his son, Joseph (Mark Wahlberg)—an ambitious young man and a rising star in his department. Together, they are committed to ridding their streets of the drug plague.

And then there’s Bobby (Joaquin Phoenix), the black sheep of the family. He’s a slick, confident nightclub manager, and feels no compulsion to be a law-abiding citizen himself. He spends his days with a rough crowd of hustlers and dealers, and his nights at his club in the arms of his beautiful girlfriend Amada (Eva Mendes). The Grusinsky family status quo is interrupted when Joseph is gunned down in the street by armed thugs with sympathies to Bobby’s operations.

Horrified by the violence he indirectly inflicted on his own brother, Bobby agrees to wear a wire and help bring down the people responsible. This noble act begins a cascade of events that will inevitably lead to his redemption as a man of the law.

WE OWN THE NIGHT marks Gray’s second collaboration with Phoenix, and their strong working relationship results in a subtle, nuanced performance that allows us to sympathize with a salacious character like Bobby. It’s captivating to watch his confidence waver as the plot thickens, and Phoenix guides his character’s arc to a dramatically compelling conclusion with nary a false note.

Wahlberg is also present for round two with Gray, sharing a similar kind of wary brotherly dynamic that they gave to Gray’s 1999 film, THE YARDS. His transformation from a slightly cocky blowhard to a haunted young man provides for an elegant counterpoint to the main storyline. In their scenes together, Phoenix and Wahlberg chew their scenes apart with a power and grasp of the material that hasn’t been seen in movies since 70’s-era Scorsese.

Also worth mentioning are solid performances by Duvall and Mendes. Duvall, a well-established and respected character actor gives the film an air of gravitas and prestige. He barely even has to lift a finger—his mere presence instantly elevates the material. Mendes takes what could otherwise be a bland, underwritten “girlfriend” role and makes it sing with bold choices. Watch the opening scene of the film to see what I mean.

Working for the first time with cinematographer Joaquin Bacai-Asay, Gray expands upon his established look by using the resources that come with higher budgets and skilled craftspeople. Shot on 35mm film at the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, Gray and Bacai-Asay preserve Gray’s signature brown/black /yellow color palette, high contrast and subdued tones. The film is Gray’s first period piece, and while he doesn’t give it a distinctively period feel, he does imbue the film with a subtly aged patina.

One thing I’ve noticed about Gray’s visual style is his embrace of light temperatures found in natural fixtures like sodium vapor streetlamps or fluorescent bulbs as part of his look. What’s colloquially called “bastard amber”—that unholy orange glare of sodium vapor streetlights—becomes a rich, elegant yellow that gives warmth to the night.

Conversely, scenes under fluorescent lights—like those of the police station—are skewed heavily towards the green/blue tones and create an oppressive, cold atmosphere. By employing light sources different from those of standard film lights, he creates a high-key lighting setup that looks natural and moody.

Gray’s camerawork also shows a subtle development. By utilizing a strategic variety of handheld, dolly, zoom and static shots, as well as periodically incorporating a stylized slow motion for effect, he creates a brooding minimalism and tension. His sound design also follows suit—an immersive, naturalistic mix is complemented by well-placed moments of directorial flair, such as the use of muffled voices and a high-pitched tone to signify hearing loss and disorientation after an explosion.

The score, provided by Wojciech Kilar, is minimal and unobtrusive. Kilar crafts a subtle soundscape of smooth strings and melancholy chords. For WE OWN THE NIGHT, Gray makes more substantial use of a number of source cues assembled into an eclectic mix of music ranging from disco to 80’s pop. Their presence gives a cocaine-fueled energy to the proceedings and firmly establishes the story’s time period in the absence of conspicuous visual cues.

Gray’s films have always painted richly detailed portraits of distinct cultures and worlds, and WE OWN THE NIGHT is no exception. Beginning with a somber prologue montage consisting of black-and-white period photographs of New York’s finest on the job, Gray makes the central conceit of his story clear—A man’s commitment to his job and to his family is sometimes the same thing.

He paints the police as a family in their own right, responsible to each other and everyone. The code of honor and family carry as much weight, if not more, as the code of law— in Joseph’s own words: “it’s better to be judged by twelve than killed by six”.

While the Grusinskys appear to be predominantly Irish or Polish in their heritage, they are part of a larger family of people coming from all creeds and nations. Their religious customs and rituals are based around social gatherings like rank promotion celebrations, or worse—funerals. It is this world that Phoenix’s character spends the movie trying to become a part of, only to find that he’s been one of them all along.

Gray shows considerable growth as a filmmaker with WE OWN THE NIGHT. He doubles down on his signature stylistic elements—all-lowercase credits, dark shadows in the eyes as the way to obscure truth—but he also shows that he’s capable of larger, thrilling setpieces. A mid-film car chase set in pouring rain is one of the film’s highlights, proving that Gray can stage action like the best of them. Indeed, there is far more action to be found in the film, complemented by a faster pace (courtesy of editor John Axelrad) and a cinematically compelling story.

WE OWN THE NIGHT isn’t a perfect film, but it’s an incredibly strong and considered crime drama. It stands shoulder to shoulder with any one of Gray’s best works, and will be most likely remembered as the film of his that is most accessible to a wide audience.

TWO LOVERS (2008)

Shortly after the release of his third feature, WE OWN THE NIGHT (2007), director James Gray was surprised to see his latest project gain funding in only four months—a timespan exponentially faster than he was used to. Most of this was off the strength of his previous films, while credit could also go to frequent collaborator Joaquin Phoenix’s rising star. In 2008, Gray released TWO LOVERS, a brooding meditation on mental instability and its effect on the trappings of a romantic drama.

As his most recently-released film, TWO LOVERS is also one of his best—if not the best. After the larger-scale set-pieces required by the crime drama conventions of his last film, Gray is now able to tone down the outside noise and zero in on the big implications of even the slightest of gestures. TWO LOVERS is a quiet, insightful work—the kind that doesn’t get made by Hollywood anymore. But most importantly, it’s a film that shows an already-mature director growing comfortably into a master of his craft.

Leonard (Joaquin Phoenix—arguably Gray’s closest collaborator) is a hapless young man who lives in a decrepit Brighton Beach apartment with his parents and works in their dry cleaning shop. His battles with being bipolar complicate his social standing and make him volatile and unpredictable. When the film begins, Leonard is still nursing the wounds of an engagement-turned-south, which forced him to move back home and regress into a state of arrested development.

His well-meaning parents introduce him to Sandra (Vinessa Shaw), a beautiful young woman and daughter to one of Leonard’s father’s business partners. Sandra is gentle, yet persistent, and soon enough the two embark on a quiet, tender romance—just the kind that Leonard needs in his life right now.

However, one day Leonard meets Michelle (Gwyneth Paltrow), another tenant in his apartment complex. She’s fiery, loud and emotionally unavailable. Leonard finds himself energized by her presence, and is compelled to pursue her romantically. Leonard juggles these two romances, blind to the fact that Michelle is completely wrong for him and will never truly be his.

All the while, his relationship with Sandra begins to falter as he becomes more distant. Soon enough, Leonard finds himself in the unenviable position of having to choose between passion and true love, and either choice will bring disastrous consequences.

Because TWO LOVERS is such a quiet, introspective film, the impact of the story falls to the quality of the performances. Gray has proven himself to be a skilled director of actors—mainly due to his preference for character-driven storylines—and his fourth feature exceeds expectations. Phoenix eschews the braggadocio of his last collaboration with Gray to portray Leonard as a lovesick, wounded animal. He’s sensitive and quiet, but there’s an emotional storm brewing inside of him.

When we first meet him, it’s during an unsuccessful suicide attempt that leaves him more ashamed than he was going in. He’s the type of person who, either consciously or not, pursues self-damaging experiences. Deep down, even he has to know that Michelle will never truly love him, but he goes for it anyway.

Leonard also takes photographs for a hobby, and it’s telling that he prefers to shoot landscapes devoid of people. It suggests a deliberate social disconnect with others, and further illustrates Leonard’s eternal state of isolation. It’s very rare that I find myself directly connecting with a character in the film, but I saw more of myself in Leonard than I would like to admit.

Without getting too personal, there was a cynical period in my early twenties that saw me pursuing the kinds of women who were all kinds of wrong for me. Of course I always knew better, but there was some deep-seated desire to get burned anyway. Leonard’s avoidance of people as his subjects suggests a fear of direct confrontation that I could sympathize with at some level. It’s a testament to Phoenix’s skill as an actor that I saw so much of myself in his character (albeit a now-more-distant, former version of myself).

Of course, any discussion of TWO LOVERS wouldn’t be complete without mentioning the event that threatened to overshadow the film completely. It’s been discussed, mulled over, and criticized countless ways, so I promise not to add too much more to the clutter. At the time of the film’s release, Phoenix was undergoing his very-public “transformation”.

He showed up to the film’s premiere hiding behind dark sunglasses and a shaggy, unkempt beard, with the word “GOOD BYE!” stamped on his knuckles. He took the opportunity to announce his retirement from acting, proclaiming that TWO LOVERS was his “last film ever” (indeed, promotional materials on the home video release of the film tout this as a big selling point).

He then proceeded to butcher every promotional appearance he made for TWO LOVERS, doing them all in character as his new persona.

Five years later, Phoenix has returned to acting, and his public “mental breakdown” was revealed to be just another character he was playing for Casey Affleck’s “documentary”, I’M STILL HERE (2010). While I applaud the dedication Phoenix applied towards his years-long physical transformation, I’m sorry to see a brilliant film like TWO LOVERS get overshadowed in its wake. If Gray himself wasn’t in on the joke, I can only imagine that there were some very terse words exchanged between the two in the days following the film’s release.

All of this (necessary) talk about Phoenix comes at the peril of ignoring the other performers. As Sandra, Shaw brings a gentle, unconventionally attractive presence to the film. She is the beauty that is always overlooked, despite always being there. It’s clear very early on that she’s a perfect match for Leonard, and we ache alongside her as he grows more distant.

Paltrow, on the other hand, is perfect as the kind of person who has regard only for herself, at the expense of others. She flits into the film in a burst of energy, and her wild, unpredictable nature combined with her natural elegance easily makes her the object of many’s affections. Known primarily for her tendency to take on glossy, “safe” Hollywood roles, Paltrow takes a huge risk here as an inherently ugly, self-centered person.

She assumes a cynical optimism that Leonard instantly connects with, and because connections to other people are so few and far between, he turns on his logic blinders and goes completely overboard. Paltrow’s Michelle is the oblivious enabler for all of Leonard’s flaws, so it’s important to the validity of the story that she embraces all the ugly aspects of her character.

Gray’s stories tend to be very insular between the main characters, so the numbers of his supporting characters are conventionally small. In TWO LOVERS, only three really make an impact. Moni Moshonov (the big bad from Gray’s WE OWN THE NIGHT) and Isabella Rossellini (daughter of Ingrid Bergman and Robert Rossellini) portray Leonard’s parents.

They are strong (at times overbearing) presences in Leonard’s world, but their profound love and caring for their son make themselves known as the story progresses. They are very much connected to the Old World, as immigrants from Eastern Europe, and introduce Leonard to Sandra in a way that’s not dissimilar from arranged marriages. These two deliver a pair of quiet, haunting performances that tell us much more about Leonard than he does himself.

Symbolizing the New World, Elias Koteas (one of my favorite character actors) portrays Michelle’s boyfriend, Ronald. Ronald is a slick, successful Manhattan businessman, but there’s a catch—he’s already married with children. He hides Michelle away in a dumpy apartment in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, and ultimately ends up leaving his family for her. In a film where each character is in some state of delusion, he’s the one who most gives into them (that he’ll be happier with Michelle than his own wife and child).

Four features in, Gray has established an easily identifiable look to his work. Working again with Director of Photography Joaquin Baca-Asay (Gray loves him some Joaquins), Gray uses his richly-detailed setting and naturalistic high-key lighting setups to create an image with high contrast and muted colors that draw from a soupy palette of browns, yellows, and blacks. Shooting in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio on 35mm film, Gray brings a very sensual feel to his gritty Brooklyn environs.

His yellow, sodium vapor nights are contrasted by biting blue tones in daytime exteriors. During this particular viewing of TWO LOVERS (my second), I noticed that Gray’s visual style is a lot like David Fincher’s, except softer. Both have a level of contrast that implies a hard edge, with colors that, while natural, skew in favor of earth tones and steely blues.

Gray’s camerawork keeps in line with his previous efforts, employing the use of tripods, dollies, and footwork to capture his images. Like his earlier films, he uses natural framing devices like doors or windows to compose his shot. However, he also uses these framing devices on a subtle level that communicates his themes.

One example that comes to mind is the scene where Leonard takes Michelle’s phone call during a lunch date with Sandra. Leonard goes behind a glass door to talk, and Gray frames the image as a close up, observing Phoenix through the window frame. Interestingly enough, the window isn’t entirely smooth- it has beveled edges that fracture and contort Phoenix’s face, producing a kaleidoscopic effect that reflects Phoenix’s conflicted feelings and self-deceptions.

Other visual techniques within Gray’s repertoire are expanded upon here. Beginning with his opening titles, Gray finally capitalizes his letters—as to why, I have no clue. He uses slow motion as a punctuation mark for key plot points, and uses shadow as a potent storytelling tool. Besides artfully using silhouettes, Gray also chooses to shoot key scenes with actors’ eyes in shadow— thus obscuring their intent and making their true message hard to read. It’s a fantastic, subtle visual device that I’m glad to see Gray continue using.

Interestingly enough, IMDB doesn’t have a composer listed, and neither does the film’s closing credits. There is very little music within the film, so it stands out when Gray chooses to incorporate it. He builds a musical landscape that harkens back to the Old World, albeit a romanticized version of it. A slow waltz on the Spanish guitar is the main musical ingredient, weaving in and out of various jazz and opera pieces (as well as a few house songs during the nightclub sequence).

With TWO LOVERS, Gray paints an intriguing story about a poor boy in a rich woman’s world. It’s notable that this is the first time we really see Manhattan in one of Gray’s films. By doing so, Gray opens up the scope of his cinematic version of the city. I should also point out that the film’s setting, present day Brighton Beach, calls back to the environs of his debut film, LITTLE ODESSA (1994). I wouldn’t be surprised to see TWO LOVERS as a well-disguised allegory for Gray’s own experiences as a filmmaker: Starting out as an eager young man looking towards the bright lights of the big city, seduced by the lifestyle and people that live inside it, disillusioned by the emptiness he finds there, and finally realizing the importance of his roots.

It isn’t a coincidence that Leonard is bipolar, either. Its inclusion in the film suggests a theme of duality that runs throughout. All of the major players lead a double life, save for the pure (Sandra, Leonard’s family). This duality creates various perversions of love and clouds judgment. For instance, look at the stark contrast between the staging of the film’s two sex scenes. Leonard’s bedroom scene with Sandra is the closest the film gets to a sense of lovemaking: warm lighting, sensual compositions, a pervasive sense of tenderness and awe, etc.

Alternatively, Leonard’s consummation with Michelle on the apartment’s rooftop is fucking: harsh/cold daylight, an observant/distant camera, erratic motions, an urgent sense of desperation. It’s the film’s single most effective communicator of Leonard’s true chemistry with these two women. Natural versus forced.

The fact that we realize this, yet the characters don’t, is very telling of Gray’s directorial style. We’re not meant to intimately connect with these characters, neither are we supposed to judge them. We dispassionately observe them through the doorways of their apartments, in their places of worship and ritual (symbolized in TWO LOVERS by a Bar Mitzvah), on their good days, on their bad days.

You could argue that this observant approach leaves audiences cold to the story, and it is very possible that this is why Gray hasn’t found a larger following. Maybe it’s a product of a more cynical age, but it could be argued that the character drama cinema of the 1970s, arguably Gray’s largest wellspring of inspiration, were equally as downbeat.

As I’ve written before, Gray’s characters are outsiders, standing on the banks of the Hudson, looking towards the glittering skyscrapers of Manhattan with hopeful eyes. You could say the same for Gray. He stands on the indie fringes of mainstream cinema–not quite obscure but not quite central either—and it’s very clear that he intends to be a great director amidst the ranks of such idols as Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola.

He already has the allegiance of Hollywood’s top tier talent– if he stays true to his roots, and continues to value craftsmanship and quality over commercialism, he doesn’t have that much farther to go before he secures his place among the greats.

THE IMMIGRANT (2013)

For the countless numbers of immigrants that braved the cold Atlantic waters in hopes of a brighter future in America at the dawn of the twentieth century, the Statue of Liberty must’ve appeared as quite the welcoming sign. Lady Liberty stood tall and defiant against the elements, offering a safe haven from the old world they left behind. To the dismay of those wide-eyed immigrants, such a promise was rarely fulfilled, and for many, it would be a promised reneged the moment their boats docked at Ellis Island.

The facilities at Ellis Island were, for all intents and purposes, the gateway into America. One would be hard-pressed to find a singular facility so fraught with history, or that has had such a lasting impact on so large a group of people. It was in the marble chambers of Ellis Island that these immigrants were given new, Americanized surnames and the circumstances of their entry into America were established, and it was here where they found out that the promise of the American dream sometimes came at the expense of their idealism and integrity.

Director James Gray’s grandparents were just two of the untold numbers people who entered America through the gates of Ellis Island. Their particular experience inspired the story for Gray’s THE IMMIGRANT (2013), a riveting period drama about hopeful lives torn apart by Ellis Island’s admittedly dehumanizing assimilation processes.

THE IMMIGRANT marks Gray’s return to the big screen after a five-year absence following 2008’s TWO LOVERS, reuniting him with longtime collaborator Joaquin Phoenix for another look into the social experience of Eastern European immigrants in New York. It’s his most ambitious film to date, and perhaps his most unappreciated—The Weinstein Company essentially dumped the film in late 2013 with little advertising or support, leaving one of the best films of the year to flounder in the home video market in the hopes of gaining the appreciation it deserves.

THE IMMIGRANT unfolds in New York City during the year 1921. Ewa Cybulski (Marion Cotillard) is a Polish immigrant who has made the long voyage to America with her beloved sister. Instead of finding the refuge they seek, they find only more hardship—her sister is taken away under suspicion of having contracted tuberculosis, and Ewa herself is scheduled for deportation due to an unsubstantiated rumor that she prostituted herself during the voyage across the Atlantic (when in reality she was actually raped).

At the last minute, Ewa is saved by Bruno Weiss (Joaquin Phoenix), a fidgety, dark man who poses as an immigration consultant at the Island so that he can recruit women into his exotic “Women Of The World” burlesque act. With very little options to choose from, Ewa succumbs to Bruno’s fold and begins her new life as a burlesque performer and a reluctant prostitute in the hopes that she’ll save up enough money to get her sister out of the hospital.

A ray of hope emerges in the form of Emil (Jeremy Renner), Bruno’s cousin and a magician going by the name Orlando. He hopes to take her and her sister away with him out west on tour, leaving this dreadful place behind for good. It’s almost too good to be true, and it is—Bruno’s protectiveness over Ewa and his debilitating jealousy towards Emil’s effortless charms thrusts Ewa directly between these two men as they fight over the right to decide her future.

Gray’s films are admired for their inspired casting, and THE IMMIGRANT definitely follows suit. He reportedly wrote the film specifically for Phoenix and Cotillard, and it shows—both actors deliver powerful, nuanced performances devoid of cliché or indulgence. As the titular immigrant, Cotillard provides a quiet, yet strong and determined presence as Ewa.

Phoenix returns for his fourth consecutive collaboration with Gray, and his first with his director after his infamous post-TWO LOVERS performance art stunt for Casey Affleck’s I’M STILL HERE (2010). Phoenix is quite adept at playing troubled, eccentric men who appear uncomfortable in their own skin, so it’s a little surprising to see him act so normal here.

His Bruno Weiss presents himself as a kindly, clean-cut businessman in a bid to inject some legitimacy into his vocation as a burlesque hustler and pimp. He’s merciful and devoted towards his girls, but he has a tendency to get carried away with his emotions. Ultimately, Bruno Weiss is a coward, and Phoenix embodies this aspect of the role with a surprisingly quiet intensity.

Jeremy Renner is dashing and debonair as Bruno’s cousin Emil, a mischievous showman who finds himself drawn to Ewa’s charms. However, behind Renner’s rakish smile lies a fundamental black-heartedness that only shows itself in a pivotal sequence, yet drives Emil’s actions throughout.

Watching THE IMMIGRANT, it’s hard to say why The Weinstein Company decided to give it such a lackluster release campaign. The film boasts stunning, unconventional performances, lustrous production design and handsome visuals—by all accounts, it should have been a contender for all the Oscars.

However, I have to admit there’s still something slightly off about the look of THE IMMIGRANT, and I suspect it may have to do with the film’s unconventional color timing. Shot by veteran cinematographer Darius Khondji, THE IMMIGRANT certainly has the “epic period film” bonafides: 35mm film acquisition, an anamorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio, and classical camerawork that gives an elegant, disciplined sense of movement and pacing to the picture.

Gray doesn’t pull any punches in referencing the look of Francis Ford Coppola’s THE GODFATHER PART II (1974), replicating its distinct golden/sepia color cast and pitch-perfect period set/costume design (courtesy of TWO LOVERS’ production designer Happy Massee). However, Gray goes one step further in an effort to distinguish THE IMMIGRANT—he applies a liberal coat of yellow onto the midtones in an effort to recreate the particular glow of electric lamps from the period.

Sometimes, however, there’s quite simply too much of a yellow cast, and the result is unnatural and sickly-looking. Combined with a strong bluish cast in the shadows that appears as if the film went through an Instagram filter, Gray’s color timing for THE IMMIGRANT deviates quite substantially from the conventional look of its genre while exaggerating the faded, amber patina of his previous films to an almost-cartoonish degree.

One nice aspect about this aesthetic, however, is that the reds cut through quite strikingly, enriching the image during the few times the color appears onscreen.

Through his original score for TWO LOVERS and music consultation services on WE OWN THE NIGHT (2007) and THE YARDS (2000), musician Christopher Spelman has emerged as Gray’s go-to guy for all things music. For THE IMMIGRANT, Spelman crafts a quiet, romantic orchestral score that never overtakes Gray’s imagery. It’s not distinctly memorable in and of itself, but it reinforces Gray’s themes and keeps everything aloft.

To give us a greater sense of the period, Gray also incorporates several folk songs—both of Eastern European and Americana origins—that provide us with a glimpse of this unique time and place in history. There’s also the appearance of a rather beautiful classical cue: John Tavener and Mother Thekla’s “Funeral Canticle”, a gorgeous chamber choir piece that can also be heard in Terrence Malick’s 2011 masterpiece,THE TREE OF LIFE.

Gray’s body of work has always assumed the point of view of outsiders relegated to the outer boroughs of New York City, looking in on the glittering lights of Manhattan, a metaphor for those who desire the American Dream yet constantly find themselves denied access. THE IMMIGRANT is easily the most literal illustration of this metaphor, anchored by the image of the Statue of Liberty standing as a beacon of hope for those who wish to enter America.

In hindsight, it’s easy to see that Gray was destined to make a movie like THE IMMIGRANTS– it’s a sublime melding of directorial conceits and thematic symbolism. There’s been a distinct progression through Gray’s filmography, with each successive film seeing its characters getting increasingly closer to Manhattan. TWO LOVERS brought its characters briefly into the island for the first time, but THE IMMIGRANT places them firmly within its walls.

After a lifetime spent on the outside looking in, we’ve finally made it to Manhattan, and now that the American Dream is within our reach, we find out that it’s nothing like we had expected or hoped it to be.

The characters that populate Gray’s filmography are firmly rooted in the Old World—there’s a heavy emphasis on family, culture, tradition, and ritual. Gray’s eastern European ancestry informs his characterization, and Ewa’s Polish background is further evidence of that conceit. THE IMMIGRANT’s drama stems from familial conflict, both in terms of biological and adopted family.

Ewa’s entire arc revolves around her desire to save her sister from the machinations of the immigration process, and Bruno’s hatred for his cousin Emil originates in his frustration and self-loathing over the fact that he possesses none of Emil’s charms despite sharing his blood. Bruno also sees his harem of prostitutes as his family, a notion that drives his possessiveness and deludes him into thinking he’s acting in their best interests. Gray covers the religious bases by making Ewa a strict Catholic, a character trait that gives us several moments of religious ritual—confession, prayer, procession, etc.

Gray has long held a talent for conveying his ideas through arresting visuals, but THE IMMIGRANT sees substantial growth for the director in wordlessly conveying his themes. His fondness for composing his shots via natural framing devices like doorways and windows is on full display, and oftentimes leads to sublimely subtle compositions that express Ewa’s alienation from this strange new world.

The last shot in particular is a knockout, and without giving too much away, uses both a window and a mirror to depict both of the protagonists facing the world before them, armed with new discoveries about themselves and each other.

THE IMMIGRANT provides a few other notable instances of simple images conveying weighty subtext. A scene in an Ellis Island holding cell sees Ewa pricking her finger and applying the blood to her lips in a bid to look fresh and healthy—an evocative parallel to similar practices by women in ghettoes and concentration camps during The Holocaust and a nod towards the innate strength and resiliency of the Polish people during hard times.

Another instance sees Emil giving Ewa a beautiful white rose, only for Gray to later show the same rose having wilted from neglect after Ewa has embraced a life of prostitution. In respect to cinema culture and history, Gray’s films have always evoked the gritty aesthetic of late 70’s drama and crime films—this is certainly the case with THE IMMIGRANT, which doesn’t attempt to hide the considerable influence of THE GODFATHER PART II on its visual style.

However, Gray’s references here also stretch even further back into cinema history, with Emil’s magic shows emulating the work of silver screen magician George Melies, or the late-second-act sewer chase evoking the climax of Carol Reed’s THE THIRD MAN (1949).

THE IMMIGRANT shows an incredible amount of growth for Gray as an artist, which the director himself recognizes—he has stated in interviews that he personally believes THE IMMIGRANT to be his best film. As his first film to feature a female protagonist, THE IMMIGRANT affords him the opportunity to expand his worldview and reap the benefits of a wider experience.

While it nominated for the prestigious Palm d’Or after its debut at Cannes, THE IMMIGRANT has inexplicably become the victim of an indifferent distributor, doomed to obscurity for the sin of not having a decent marketing budget. A studio’s faith in its product should by no means ever be an indicator of its quality, and those who care seek out THE IMMIGRANT will be rewarded with something of a masterpiece.

Gray has always shown remarkable restraint in his aesthetic, but THE IMMIGRANT sees him mature exponentially as an artist and places him in the league of Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, and the other premiere chroniclers of the New York experience.

COMMERCIALS (2013-2017)

Due to his ferocious commitment to his own artistic integrity, director James Gray has weathered a difficult career trajectory partly of his own making. His 2013 feature, THE IMMIGRANT, was a stunning work of uncompromising cinematic art, but its botched rollout and limited audience appeal doomed it to failure from the start.

As such, it was going to be a while before he could summon up enough professional capital for his next feature. In order to sustain himself in this prolonged drought, Gray followed in the footsteps of many filmmakers before him and turned to the world of advertising. Here, he had immediate value– ad agencies desired his services because his reputation in the feature realm attracted well-known celebrities and film stars.

From 2013-2017, Gray developed his talents in the commercial sector with three efforts that, while not necessarily advancing his own artistic growth, further developed and refined his technical capabilities with varying aesthetics.

CITROEN: “IMPOSSIBLE” (2013)

A European ad that American audiences have only been able to see online, Gray’s 2013 spot for carmarker Citroen applies a stylish cinematic look befitting the participation of a director like him. Titled “IMPOSSIBLE”, the spot features Ewan McGregor on the receiving end of an interrogation by TWO LOVERS’ Vinessa Shaw regarding his car’s performance features.

Gray employs a cold, metallic aesthetic to match the sleek modern environs, framing his subjects in his signature style– through architectural elements like the glass fish bowl of a conference room. Gray indulges in the genre aspects of the spot’s story, crafting a slick little spy thriller that reminds one of a toned-down Tony Scott effort.

CHANEL: “BLUE” (2015)

Gray has often been painted as an acolyte of Martin Scorsese thanks to their shared interest in the social history of New York City. With 2015’s Chanel commercial, “BLUE”, Gray avails himself of the opportunity to directly follow in Scorsese’s footsteps, crafting something of a sequel to his stylistic predecessor’s well-known Chanel spot starring Gaspard Ulliel. Ulliel returns here, desperately seeking solace from the dizzying whirlwind of celebrity while Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along The Watchtower” blares on the soundtrack.

Gray replicates the aesthetic of Scorsese’s earlier effort, applying a metallic cobalt sheen over the dreamlike visuals. The piece exemplifies Gray’s natural, heretofore-unknown talents with a high-fashion visual style, with the director peppering flashy elements like bright lens flares and ethereal double-exposures throughout Ulliel’s existential journey.

LANCÔME: “LA VIE EST BELLE” (2016)

In 2016, Gray was hired to direct a spot for Lancôme titled “LA VIE EST BELLE”, which provided him with the opportunity to direct the fashion brand’s spokesperson, Julia Roberts. The spot’s loose narrative finds Roberts escaping a boring dinner party in an elegant French mansion and breaking out into a lively garden party with a romantic view of the Eiffel Tower.

Gray uses the same glittery, high-fashion sheen that he did with Chanel’s “BLUE”, albeit in a warmer tone that favors a pink/purple color cast. “LA VIE EST BELLE” is a fairly anonymous spot from an artistic perspective, but Gray nonetheless delivers a strongly-realized and confident effort that matches Roberts’ star-wattage.

THE LOST CITY OF Z (2016)

Looking over director James Gray’s filmography to date — a series of hard-hitting dramas set in New York — one could be forgiven for not seeing a David Lean-style epic about exploration and adventure in the Amazon jungle in his immediate future. Even Gray himself initially didn’t see it; he didn’t understand why Brad Pitt’s production company, Plan B, had sent him a gallows copy of David Grann’s 2009 novel “The Lost City of Z”.

(1) He had just finished the understated relationship drama TWO LOVERS (2008), and it was still five years before audiences would witness the lavish grandiosity of THE IMMIGRANT’s historical affectations. Nonetheless, Gray found himself curiously drawn to the story of the real-life adventurer Percy Fawcett and his quest to discover a lost civilization in the Amazon amidst the backdrop of the turn of the 20th century and The Great War.

He was reminded of a sentiment he had applied to all his prior works, espoused by writer George Elliot’s proclamation that “the purpose of all art is the extension of our sympathies” (2). In other words, THE LOST CITY OF Z invited Gray, through the process of filmmaking, to discover his own emotional connection to the material while venturing far outside his comfort zone. Indeed, the production of THE LOST CITY OF Z would be filmmaking as adventure, seeing Gray and his collaborators travel deep into the jungles of Columbia with little in the way of infrastructural support systems.

A formative experience in Gray’s artistic development had been his first viewing of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 masterpiece APOCALYPSE NOW, and THE LOST CITY OF Z offered him the opportunity to chart similar territory. He went so far as to write to Coppola and ask for his advice about shooting in the jungle, to which Coppola simply replied “don’t go”. A warning, to be sure, from someone who had famously come close to the brink of insanity while shooting a movie in the dense jungle, but also a challenge– one that Gray couldn’t possibly pass up.

In detailing the exploits of British explorer Percy Fawcett’s expeditions to the jungles of Amazonia, Gray condenses the book’s eight separate journeys into three, structuring them into tidy narrative acts. Charlie Hunnam anchors the film as Fawcett, gradually becoming a more distinctive and nuanced character as he grows more obsessed over the decades with the mysterious lost civilization he calls “Zed”.

We first meet Fawcett as a Major in the British infantry in 1905, where his background as a cartographer positions him as an ideal candidate to head up a mission for the Royal Geographic Society, represented by Ian McDiarmid’s Sir George Geordie. Tasked with surveying the border between Bolivia and Brazil in hopes of quelling a brewing regional conflict, Fawcett is accompanied by Costin (Robert Pattinson; unrecognizable under a bushy beard and spectacles), a fellow explorer fated to become one his closest confidantes in the coming years.

As they travel down the river in a rickety boat and contend with various aggressions from the locals, they become aware of the rumored existence of a lost city hidden deep within the jungle that promises to yield precious insights into human development in the region. Upon completion of his mission, Fawcett returns home to his family in England– his wife, Nina (played by Sienna Miller as something of a burgeoning Suffragette or proto-feminist), and their handful of children.

Having grown accustomed to the awe-inspiring vistas and boundless freedom of the jungle, Fawcett inevitably finds himself chafing against the rigid conventions of privileged British society. He organizes another expedition in the mid-1910’s, this time with the intent of finding the fabled lost city of Z. This particular trip doesn’t prove as successful, and he returns to England just in time to fight in the trenches during World War I.

A battle injury sidelines him for several more years, and it’s not until 1925 that Fawcett organizes one last journey into the beating heart of Amazonia, this time accompanied by his adventurous young son, Jack (Tom Holland). It is here that Fawcett will face the ultimate test of his convictions and answer for his all-consuming obsession of finding a mythical city that may or may not exist.

Gray presents THE LOST CITY OF Z as something of an anti-adventure film that’s more concerned with story and character rather than outright spectacle. That being said, he does indulge in frequent moments of epic, David Lean-style cinematography. Reteaming with Darius Khondji, his cinematographer on THE IMMIGRANT, Gray captures THE LOST CITY OF Z in the very appropriate format of anamorphic 35mm film.

Gray’s choice to shoot celluloid may seem like an insignificant aspect of the production, but it was undoubtedly a major decision with profound implications for the director and his producing team. Aesthetically-speaking, Gray felt that celluloid possessed a distinct melancholy or nostalgia apropos of a period epic such as this. Logistically-speaking, he feared that the overwhelming humidity of the Colombian jungle they would be shooting in would quite literally fry any hard drives or digital equipment they lugged along the way.

This isn’t to say that photochemical film didn’t pose its own unique challenges; indeed, due to their exceedingly remote location and its utter lack of infrastructural support, production had to devise a rickety shipping system that carried the inherent risk of exposed film never making it to the laboratory for processing.

Thankfully, no such issues arose during the shoot, and all can witness the glorious visuals that Gray has committed to film here. THE LOST CITY OF Z renders Fawcett’s grand adventures in a heavy golden cast not unlike THE IMMIGRANT’s visual aesthetic. These bold yellow highlights compete for clarity amidst naturalistic earth tones and deep, heavy shadows stained with the slight tinge of teal. Also like he did with THE IMMIGRANT, Gray draws heavily from the influence of Francis Ford Coppola, fusing the aesthetics of THE GODFATHER PART II (1974) and APOCALYPSE NOW (1979) to create a stately, albeit gritty, vibe.

He also pulls from Stanley Kubrick’s BARRY LYNDON (1975) and Luchino Visconti’s THE LEOPARD (1963), seen most immediately in the mise-en-scene of sequences set back in the stuffy social circles of Victorian/Edwardian England. Gray’s compositions and camera movements mix the classical formalism of vintage epics with the handheld immediacy of his New Hollywood influences, and even utilize swooping helicopter shots for added visual grandeur.

He also incorporates several visual conceits that bear his signature, like the use of natural framing elements such as natural foliage and tree trunks (akin to his framing of his subjects through doorways in his previous work). Composer Christopher Spelman brings musical consistency to Gray’s filmography by returning with an effective (if not entirely memorable) suite of cues that strike a balance between the sweeping romantic strings of old-school epics and a pounding percussion that conveys the throbbing heart of darkness that lies deep in the Amazonian jungle.

For a story that even Gray himself could not initially see as a proper vehicle for his particular set of thematic tastes, THE LOST CITY OF Z packs in a fair amount of the director’s key artistic signatures. A soaring adventure picture indeed seems to be worlds away from the gritty and intimate chamber dramas that made his name, but Gray nonetheless finds several points of access.

His films are almost uniformly marked by a distinct outsider’s perspective, embodied best by protagonists relegated to the outer boroughs of New York City and forced to gaze at the dazzling lights of Manhattan from afar. Even the ones firmly inside the island are outsiders, such as THE IMMIGRANT’s Ewa Cybulska attempting to comprehend and assimilate herself into the confusing new world of early 20th-century Manhattan.

THE LOST CITY OF Z retains this perspective by virtue of dropping a British aristocrat into the green labyrinth of South America, forced to communicate with the indigenous peoples who inhabit it. Even when he travels back to England in between expeditions, Gray casts Fawcett as an outsider in his own home, finding himself increasingly at odds with the privileged circles that can’t comprehend his experience in the wilderness.

His films are also characterized by a fascination with the rituals, traditions and heritage of The Old World. A distinct Eastern European and Jewish character runs through the narratives of LITTLE ODESSA down on through THE IMMIGRANT, an identity upon which Gray can examine the juxtaposition of these ancient social and familial structures, ethical values, and various religious dogma against the modern melting pot of New York. In Gray’s films, New York can still be thought of as “The New World”, precisely because it is seen through the prism of the American immigrant experience.

THE LOST CITY OF Z further explores these conceits, depicting Amazonia as a literal New World completely alien to the Old World perspective of Britain during the Victorian/Edwardian era of the early 1900’s. Gray trades his signature Eastern European flair for insights into Anglo-Saxon culture through their various customs and rituals, seen best in the opening sequences where Fawcett leads a rousing deer hunt on horseback and dances the waltz at a high society gala shortly thereafter.

This approach is also applied to Fawcett’s brush with the indigenous tribes of Amazonia, with several sequences depicting his observation of the natives’ unique ceremonial traditions. He regards these communal experiences with awe, gaining a sense of connection to their innate humanity while growing increasingly contemptuous of the Old World culture he comes from.

Despite being three years removed from its predecessor, THE LOST CITY OF Z asserts itself as something of an informal companion piece to THE IMMIGRANT. On the surface level, both are handsome, impeccably-shot historical dramas about the search for individual identity amidst an alien environment. They even share similar ending shots, framing a key character in the reflection of a mirror as he or she walks away from us. Together they represent Gray’s emergence as a mature director with a timeless aesthetic that promises to install him in the pantheon of great American directors.

Of course, this assertion is dependent on the successful completion of future works at a similar level– something that Gray himself isn’t so sure will happen. In recent years, he’s spoken at length to the media about his disdain for the current climate of American studio filmmaking, and how overwhelmingly difficult it is, even for someone of his stature and pedigree, to finance the types of projects he wants to make. Indeed, while THE LOST CITY OF Z was hailed by critics, audiences apparently decided the lack of superhero tights or shared universes in the film was a liability and mostly stayed away.

In the end, the film made back roughly half of its production budget in box office receipts, delivering the kind of financial performance that makes it harder for Gray to command the level of funds he needs to realize future projects. He could follow in the footsteps of other filmmakers and make the jump to prestige TV, and with his recent foray into commercial production he has already dipped his toe into those waters. At the same time, his dedication to the art of cinema is so absolute and uncompromising that he very well might view episodic televised content with a fair degree of distaste.

While we wait for news on what form Gray’s next project will take, THE LOST CITY OF Z stands as the pinnacle of his technical achievements. In flexing his muscles outside of his signature milieu of urban crime dramas, Gray evidences a remarkable diversity in his tonal reach, delivering the harrowing intensity of war and the romanticism of adventure with similar aplomb. It remains to be seen whether THE LOST CITY OF Z will attain the classic status accorded to the vintage epics from which it derives its inspiration, but it’s already clear that it is stands as Gray’s most ambitious and technically-accomplished works to date.

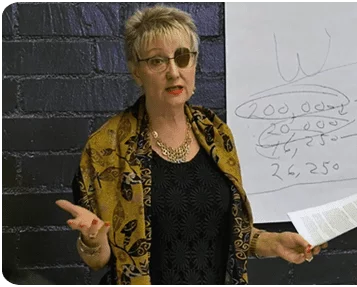

Author Cameron Beyl is the creator of The Directors Series and an award-winning filmmaker of narrative features, shorts, and music videos. His work has screened at numerous film festivals and museums, in addition to being featured on tastemaking online media platforms like Vice Creators Project, Slate, Popular Mechanics and Indiewire. To see more of Cameron’s work – go to directorsseries.net.

THE DIRECTORS SERIES is an educational collection of video and text essays by filmmaker Cameron Beyl exploring the works of contemporary and classic film directors. ——>Watch the Directors Series Here <———