Right-click here to download the MP3

I’m so excited to bring this episode to the IFH Tribe I can barely contain myself. Today on the show we have ex-distributor turned filmmaker Jeff Deverett. Jeff reached out to me after reading my book Rise of the Filmtrepreneur: How to Turn Your Indie Film into a Moneymaking Business. He wanted to tell me that the book hit the nail on the head and that my film distribution chapter was right on.

I came to find out that he was an ex-distributor and had was on that side of the business for 20 years. We got to talking and I asked if he would come on the show and spill the beans on:

- How a bad distribution deal is structured

- Why the entire film distribution business is systemically designed to screw the filmmaker

- How a distributor negotiates a deal from his point of view

- How to follow the money

- What a filmmaker needs to do NOT to get taken advantage of

After this episode, you will know “where the bodies are buried.” As Jeff said on the show

“It’s not the film distributors want to screw over filmmakers is it just happens organically.”

We also go into his Filmtrepreneurial business model. He has directed seven feature films, three of which are currently playing on Netflix. He self-distributes all his films. Jeff is a producer, director, writer, and actor known for Full Out 2: You Got This! (2020), ism (2019), The Samuel Project (2018), Kiss & Cry (2017), Full Out (2015), King of the Camp (2008), and My Brother’s Keeper (2004). Jeff’s successful film and TV career began with distribution with New World Entertainment, Astral Communications, Anchor Bay Entertainment, and his own company, Deverett Media Group.

We go into:

- How and why he chooses his niches

- How he leverages “the niche” in his filmmaking and marketing

- Why Netflix has one of the fairest distribution deals in the business

- and much more…

This episode is going to be EPIC. Sit back and get ready to have your mind blown. Enjoy my conversation with Jeff Deverett.

IFH Academy’s Film Distribution: Confidential Course

I’m also announcing the BETA Launch of IFH Academy’s Film Distribution: Confidential Course.

As part of the BETA team you will get:

- Massive discount for early adopters

- Be the first to see new lessons as I create them

- Access to me during the creation of the course

- Give feedback on the lessons and request new lessons

I want this course to be the most comprehensive course on film distribution anywhere in the world and having you be part of the BETA Team will help me do that.

Alex Ferrari 0:32

Today's guest is Jeff Deverett. And Jeff is an ex distributor who has turned into a filmmaker. Jeff had been in the distribution side of the business for almost 20 years and has been making films as a filmmaker for the past 15 years. He has directed seven feature films, three of which are on Netflix. Currently, he self distributes all his films and only after he switched from The distribution side to the filmmaker side, did he realize what the hell was going on? And how filmmakers have everything stacked against them when walking into a negotiation for a film distribution deal? Now, Jeff reached out to me after reading my book, Rise of the filmtrepreneur, and really want to just talk about the book and the concepts in the book, and congratulated me on the distribution chapter in that book, because it was really right on. So as I was talking to Jeff, I found that he was obviously an ex distributor, and I asked them, would you be interested in coming on the show? And kind of talking about distribution? And how distributors do those kind of tricks that they do, to kind of screw over filmmakers in many ways? And he said, Absolutely, I know where the bodies are buried, I'll be more than happy to share everything. And when I finally recorded this episode, Jeff did not disappoint. He laid out so many golden nuggets on the mindset of a distributor on how how the industry has just been built this way, how the deals are structured, how you follow the money, how you can negotiate certain aspects, what kind of clauses you might need to protect yourself, when to walk away from a distribution deal, when to you know, maybe not get everything you want, but move forward with a distribution deal. It is it was just mind blowing. It was just an insane conversation. And we also talk about how he's using the film intrapreneur method has been using the film entrepreneur method for years in regards to how he is using niche filmmaking, and how he's been able to really build a business around his filmmaking passion. This is an epic conversation. It lasts over two hours long, so I need you to strap in, get ready to take notes. And prepare yourselves to have your mind blown. Without any further ado, please enjoy my conversation with Jeff Deverett. I like to welcome the show, Jeff Deverett. Man, how are you my friend?

Jeff Deverett 7:24

I'm great. Thanks for having me.

Alex Ferrari 7:25

Oh, man, thank you for doing this. I appreciate it. You know, you and I have been talking for a couple weeks now going back and forth on some stuff and and the idea was like we you know what you think it was yesterday? Would you like me to come on your show to talk about all things distribution, because I know where that bought, if I may, quote, I know where the bodies are buried. So I was like, Well, yes, sir. Yeah. Do you want us to blur out your face? You're like, No, No, I'm fine. So um, before we get into it, tell the audience how'd you get into the business?

Jeff Deverett 7:59

Okay, so you're gonna hear from my accent that I'm formally from Canada. I now live in San Diego, California with beautiful San Diego. So, but I lived in Toronto, Canada for most of my life. And my wife and I decided because we want to make a lifestyle change, mostly because of the winters in Canada. As you and I agree, Toronto is a great city. And it's a great film city, by the way, too. But it is nasty in the winter. And we were eat, she's American. So we were able to make that change. So that's why we ended up in the United States. And I'm now a citizen, very proud. And actually, a couple days of july fourth, I take that very seriously. So I celebrate like fourth. Okay, anyways, how to get in the business. So I got what you call the bug, the virus, you know, for lack of I got that virus, which is the filmmaking virus at about 16 years old, I recall. I don't know why I got it. I just, I just got the virus that I needed to be a filmmaker. And so when I was going to college, in an 18 is in in Canada. My dad said, so what do you think you want to do? And I said, I want to be a filmmaker. He said for Really? And I go Yeah, I think I do. Yeah, he goes, do you want to be a producer or director? And I said, I don't know. What's the difference? No, no, he didn't even know this crazy conversation. But this is what literally went on. And he said, Well, if you want to be a producer, I think you should like either go to law school or business school should either get an MBA or to law a law degree because I think there's going to be a lot of business involved. But if you want to be a filmmaker, like a director, go to film school, because you know, it's all artistic. So I said, I think I want to be a producer. And anyways, I went and got an undergrad degree, a business degree in economics and finance. And then I went to law school and got a law degree. And then I went right into like, a practice in Canada. You have to practice law for one year. It's you know, to do it. Because sort of an apprenticeship. And then right after that, I only own companies, I wanted to be in their legal department. So and I ended up at first as a small indie company, but then in a big sort of, you know, quasi studio as big as they are in Canada, a public company, a media company. So when I was being hired into that job, I thought I was being interviewed for the legal department, but they ended up putting me in distribution, and I went into sales. And I said, this is unusual. They said, well, you have the right personality for sales. So and we'd like your background, and we know you can talk business and negotiate contracts. So we're going to put you into the sales department. And I had no clue. I mean, I literally thought I was going into the legal department into business affairs. So I said, Yeah, this is fun. Because I got to go to all the markets, you know, I got to literally travel the world go to all the markets. So my job was to basically acquire indie films, and programming TV, both TV and movies. And to set it up for distribution. Ultimately, I phased into the selling side, as opposed to the acquisition side. And then I started running the domestic sales operations internally in the studio. And then we branched out into lots of different things. As you say, you know, you got to be like your film trippin Earth book, which I read, by the way, and enjoyed. Thank you. So we branched out into lots and lots of different merchandise. And it wasn't just about the programming, it became a full business in terms of how we can monetize lots of other things.

Alex Ferrari 11:39

So how do so what are the two? That's just curious what other products or what other things that you were what other revenue streams are coming in from the films?

Jeff Deverett 11:46

Well, I don't know if you totally reviewed my my bio that I sent you.

Alex Ferrari 11:50

Oh, there was I do remember? Yes. Yes. Please tell the audience. There was this one, there was this one, this one small IP that you guys

Jeff Deverett 11:57

One small little item? And I hopefully we're talking about the same thing, because we didn't talk about it. But so my biggest acquisition by far for the Canadian market? Was this purple dinosaur called Barney Yep. Yeah. So for those of you who remember, Barney, you know, was gigantic, gigantic, you know, children's property. And if for those of you smiling, because you probably your kids were probably hooked on it. Anyways, I met this woman named Cheryl Leach, at one of the conferences in Las Vegas. At that time, Barney, she had just made three videos, Barney was actually blue wasn't purple was a different voice was a different thing. And I had at the time, and I was very, you know, programming for kids. And I meet this school teacher Cheryl Leach. And she tells me that this property and that she's a school teacher, and she knows what kids resonates with them. And I, I brought it back to, and I said, Guys, we should acquire this. I don't know why there's something about it. This woman kind of just is she's connected. She's hooked into what the audience really wants. So we acquired it. And sure enough, Barney, like, within a year, got onto PBS and became like, what it was, she changed the color, you know, and it grew and grew and grew, and it became this fantastic property. Anyways, originally, we just acquired, I just did the routes for, you know, basically the programming, which was television and home video, at the time, and home video was monsterous, with VHS at the time. And then we transitioned to DVD. And we, you know, over the first couple of years, we developed a really good relationship. And she said, You know, we're doing all this other stuff, like we're doing all these, you know, all these licensed brands, like plush dolls, and books, publishing, music, toiletries, clothing, and, you know, like, there's a lot of opportunity for that in Canada, because, you know, a lot of it's not license and I said, Okay, where do I sign up? And we've got everything we got, we became the music publisher, the book publisher. I mean, it was just the biggest was the

Alex Ferrari 13:59

Money just printing money, printing money.

Jeff Deverett 14:02

Plush dolls was the biggest and then we realized that the the show is just a TV commercial, really to sell, to get people interested to sell merchandise. And we did concerts, and we did so much stuff. And it was first of all was a lot of fun. Secondly, I learned so much about Merchandising, and, and until rewrites that type of thing. Um, there was tons and tons of piracy dealt with, of course, everything was being pirated at that time. I mean, you know, you'd make a plush doll A week later, some ripoff doll would appear in Walmart from nine and up from some other distributor and yeah, I mean, it's spent a lot of time dealing with that. But it was it was monstrous Now, the only thing is I didn't own that company. I was working for a public company. They were great guys, and I enjoyed it. But they made a ton of money. And the people like the back then when we started was called the lions group became lyric studios and ultimately hit entertainment, bought it and great, great property. And you know,

Alex Ferrari 15:01

so that is, okay, so the Barney the Barney lady Cheryl. She actually made money with this deal. Oh, she made tons of money. So okay, and we're gonna get into why that deal made money and a lot of others didn't. But you did this during the 90s. And I'm mistaken, right. 90s, early 2000s

Jeff Deverett 15:23

Yep, that was mid mid 90s. And yeah, mid 90s 96 I like property. Yep.

Alex Ferrari 15:28

Okay, so cuz I remember when I was, I was still like, 93 I was working 92 I think 9293 I was still working at a video store. And, and Barney, just so much, Barney. Yeah, it

Jeff Deverett 15:42

might have been 9095. Maybe I started there. 94 Yeah. And it was early on. So yeah,

Alex Ferrari 15:47

it was around there. But I remember we had plush dolls. And like you couldn't keep anything, Barney. And it was it was insane. So can you tell the audience a little bit about what it was like in the 90s with distribution in the sense that, you know, VHS was obviously King. Basically, you could almost put almost anything out on VHS, and you would make money with it. Is that a fair statement?

Jeff Deverett 16:13

Okay, well, let's just finish the Barney thing first. Okay. Barney was that I wouldn't even call that independent filmmaking. It started off as a TV show. But it became an entire, you know, licensing and merchandising business. That's what that is. So in that it's not really independent filmmaking. So let's switch gears. And I'll tell you about the 90s. So I started off primarily in television, because video was just starting. And you know, I mean, you can figure out my age, if you will, I'll tell you, I'm 59 years old. And I started right out of law school at 26. So I've been doing it for a few years. And so VHS had just launched. And basically, you know, we were all like trying to figure out, like, how do we make money with this? You know, because some of the, you know, the big block, like, you know, the big video chains, Atlantic blockbuster and stuff like that. And so we originally were selling there was no sell through it was just rental. So we were selling VHS tapes for about $110 correct. We were selling it to video stores, they would do the rentals and that's how it went out. But and then I remembered the first movie that they attempted to sell ETS No, no, that was no there was one I think was Top Gun. It might have been I thought it was Top Gun.

Alex Ferrari 17:34

It might have been an Indiana Jones or might have been a Top Gun. It was one of those Yeah, it was one of those I remember et was the thing that blew me

Jeff Deverett 17:42

out of the water. Yeah, so and the studios were taken they were going to take a chance with that because that was kind of breaking the mold going and selling directly to consumers through like stores like Walmart as opposed to blockbuster you know, and back then it was $30 you know to buy a VHS tape it wasn't you know $10.12 so that was a whole new business model we were all thinking oh no, there's no way anybody's gonna buy that because they can rent it for you know, 399 or 499 and a blockbuster store and sure enough, you know, took a probably a year to develop that market and that became the business you know, now the rental business was still pretty strong but you know, the sell through business became everything and then of course DVDs came along so we just changing format but the sales process was all still the same. And you know, those were I mean semi I'm going to call it glory years I mean the

Alex Ferrari 18:34

The money was flowing the mean money was flowing like crazy.

Jeff Deverett 18:38

Well people and people were enjoying it like people want it to own you got it you got like a piece of merchandise you got like a nice box you got a you know, item so and you had people were collecting like libraries were developing so and you know, you could watch it over and over again we had special special features was a gigantic element to put on to the you know, all the DVDs and but you said something earlier you said you could sell anything. The truth was you pretty well could sell anything. As long

Alex Ferrari 19:06

as I had to listen. Listen, I I had I had an my film in my mind because I know this because when I was working in the video store in the late 80s, early 90s the stuff that would come in there was the Slimer Rama bowl Rama. There was assault of the killer bimbos, which was literally two three girls flying like that with book popping bubblegum. The exterminator which is obviously a ripoff of the Terminator, and then anything that Roger Corman put out like it's it was insane. You could literally put out and I remember the guy driving up to the front of my mom and pop it was in my shirt about the mom and pop shop that I work that he would drive up with a van It was like so city he would open up the back of the van and he would have just VHS is lined on the walls like you could walk into the van and pick out titles to buy and they were like unit they weren't like the dick studio stuff. It was all the indie stuff. And we would buy a boat like, oh, that that cover looks good, right? Let's put it on the shelf. And that's what we'd rent. And you could, it was just a, it was a gold rush. It was a gold rush and DVD. And I think that's the whole, I think Hollywood basically leaned on that DVD market so much and VHS market, it was their entire business model. Yeah,

Jeff Deverett 20:20

we came the primary revenue source for sure. For many, many years. And, and for good reason, you know, people had fun, like, it was an event to go to a blockbuster store, you know, you go there, and you'd walk around and look at all the different titles. And you never heard of any of this stuff, like you said, but but it was fun to do it. I enjoyed doing that.

Alex Ferrari 20:36

Yeah, it was a lot. It was a it was a different time, it was a different time. So Alright, so you're now in distribution, and you obviously are handing out deals left and right. And you're talking to independent filmmakers, you're talking to content creators. And when you were in the sales side of things, you know, when we spoke earlier, you know, you just like well, Alex, you know, I didn't knowingly try to screw over filmmakers. That was just the way the system is kind of set up. Can you elaborate on that? A little bit? Yeah, for sure. Yeah.

Jeff Deverett 21:08

I mean, here I am. I, you know, I'm 26 I get hired by a big large media company to go into their entertainment department. And, you know, what do I know, I'm, you know, I'm fresh out of law school and new to the whole industry and every like that, and they said, Here's how it works. You know, I'm not taking, you know, like, I'm not trying to make excuses or anything, but like, you got to learn, right? Here's how it works. Here's how the distribution business works. Here's how the deals are done. Here's how. And I was a sponge. I just absorbed it all. And I went with the flow because I was working for them. And this is what you do. And this is how, you know you're learning. Right?

Alex Ferrari 21:43

And by the way, to your defense. That's this just as the system back then and the 80s in the night like that. There was no options. And everybody did business this way. There wasn't like there was no self distribution was no, there was no there's nothing. There's no such thing.

Jeff Deverett 21:58

Yeah. Yeah. So this, this is how it was done. Yeah. So. So I said, Okay, I can do this. I mean, I'm learning and you know, I'm trying my best and being diligent and going with the flow and everything like that. So it wasn't literally until 2004 when I decided to make my first feature film, that I really understood what was going on. So I'm not an evil guy didn't want to screw anybody or give bad deals aren't like that. That was the business. And then when I realized that I'm on going to be on the other side of this equation, right? All of a sudden, the light turned on and said, Hey, wait a second. This kind of doesn't make sense. You know, and for all the people, you know, who are maybe listening who did a deal with me in the early years, I'm sorry, if I gave you this episode, your penance? I didn't know any better Honest to God, I didn't

Alex Ferrari 22:50

know and look and to be and to be fair, to you, Jeff, like again, in that time period, it that's all there was, there was just no, there was just there was no other options. And everybody was given the same deals, which were horrible deals, or many times, because if you didn't like it, you just go like, Don't take it and go somewhere else. But the other person that they'll give you the same deal. So there weren't a lot of options for filmmakers. But there were obviously some makers, some filmmakers, were making money. Obviously, somebody was making money somewhere, because it's not all one and one and done. So was it because they structured deals differently? Maybe they had, how does that work?

Jeff Deverett 23:26

That's exactly it. Here's the thing is the distributors aren't evil. They're just business people, they're business people in a business that's designed to be skewed in their favor. That's all that's all it is. But they're not bad people. Some of them are bad people, but they're not bad people. You know, the deals are bad. That that's the problem. You know, think about like, a film is a major major thing in somebody's life in a filmmakers life. It's it's as big as and I shouldn't compare it to this, but it's almost as big as having a child. You put your heart and soul into this, you put all your financial wherewithal into it. You spend months and years I mean, it's a big big deal. And you know, it can change your life or it could you could go broke, you can make a you know, do well. I mean, it's a big, big deal to make a movie. All right. So if you like that other it's a major asset also. Now think about that biggest asset in most people's lives is if they buy a home. Now think about this. Okay, I was I was thinking about our discussion we're going to have today and I want to compare it to home buying, like when you buy your first home, you're a little naive, your little green around the ears and everything like that, but but you're still smart enough to know that they put a list price up and you can negotiate it. You don't necessarily have to pay the list price. They say this is what we're asking. But you know, make us an offer. And you know, so you it's negotiable. Right? Now when you go to that's buying on the selling side, when you go to sell your House, like, you know, the agent says, Okay, I want a 6% commission and you say, Well, wait a second, why can't we do it at a 4%? commission? You know, it's it's fair game to ask those questions. Because there's a lot of money at stake. And this is your major acid in your life. And you know, like, you get one shot to do it. And hey, like, he had a lowball offer, you say, you know, thanks a lot. But I want you right back at a higher price. This is regular standard operating procedure in real estate for a major asset like a house. Why isn't that the case? With indie films? Why does a filmmaker basically walk into a distributor and they put a deal in front of them, and they kind of think, Oh, this is what I have to live with. And the and and here's the reason is, because they don't know any better, they don't know that they can actually negotiate it, they don't know that they can push it, they don't know, they sort of don't know, the right questions to ask and know where the give the give and take points are. And you know, like, it doesn't hurt to ask, I'm not saying you're necessarily going to get it. But the reason the deals are primarily bad in, in the film business is because one side, one party to the deal doesn't know as much as the other party. ie the filmmaker just does not come armed with enough knowledge and experience as the distributor does. So they're always going to, I'm not gonna use the word bully, but they're going to negotiate a better deal for themselves, because the other party doesn't really know how to negotiate that deal. And that's why that's why a lot of indie filmmakers get screwed not because a distributor they're in business to make money. They're business people, right. And if they can do a better deal for themselves, then you know, fair's fair, that's, that's their business. Now, they know darn well, that the other guy on the other side of the table is really not suited to negotiate that deal. And, by the way, a lot of the lawyers that that in, right, don't make bring in, they also don't know what they're doing. I've seen so many lawyers screw this up, because, you know, they're there. They're a real estate lawyer, or their family law lawyers, something like that, you know, they're not specialists in this area. So it's not like, like, you know, something you talk about in your book, and on some of your podcasts, he's talked about, like the 15 year term, like that is ludicrous, 15 year terms, but if you're a distributor, hey, why not ask for 25 year terms, like, hey, they're long, you can get your distributor, take what you can get, right. But, you know, on the filmmaker side of the piton, like, it's giving a 15 year term without, you know, outs like performance, you know, guarantees and stuff like that. But for a lawyer to not question that. I mean, like, Saturday? Well, the reason they wouldn't is because they don't know, they think okay, maybe you know, these guys have been in business a long time. They're big, legitimate company, maybe that's the standard procedure.

Alex Ferrari 27:51

So that's also, I want to stop you there for a second so that the big distributor, okay, so there's, and again, we're not talking Warner Brothers universal, we're not talking. We're not talking to majors, we're talking, talking, not talking about studios, we're not talking, that's a different conversation. All right. Independent, independent companies, there are a handful out there who have a lot of perceived value based on their name, that they're big, that they're kind of everywhere, that they're releasing movies all the time. And they've positioned themselves in the in the filmmaking space, and the independent filmmaking space, as a, as a player in the end as far as getting films out there. And there's this kind of almost honor associated with being a part of their library, to say, Hey, I got released by these guys. I'm not going to get paid. But I could say that I got released by these guys. And like, what are their business? Does that make sense?

Jeff Deverett 28:51

Hold on, hold on, let me defend them for a second. Let me defend them. First of all, they know what they're doing. I mean, most distributors, they're in the business, they know how to sell, they know where that they know, they know how to do the deals in the international marketplace. That's what they do day in, day out. So you know, and they, a lot of them are good at doing it. Right? The problem is the deal. It's not necessarily okay. There are some times when a distributor will take on your movie and not do anything with it. You know, but that's not there. But they're not interested in that they don't want to waste their own time and money. They generally want to take on stuff that they believe they can do stuff with which we'll get into in a second. Okay. But the problem is the deal that just the deal skewed more in their favor. But like if you you know, the distributor generally wants to do a good job because the, the better the job they do, the more money they make, like the more revenue they can generate, because they're generally working on a percentage, the more money they can make, so they're not in the business to screw filmmakers. That just happens organically because the deals are set up the wrong way. I will do

Alex Ferrari 30:00

a second I can't we just stop there for a second. I just we have to, we have to rewind that I need to, I need to focus on this a little bit. It's not that distributor screw for this. I'm gonna put this on a T shirt. And then I start the film distributors wanted screw filmmakers it just happens organically that should be a T shirt, I want you to put it in my store and sell it. That is brilliant. Can you imagine walking? Can you imagine walking AFM with that shirt? Everybody would say Where can I get one of those? Awesome? Well, nowadays, absolutely. We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show.

Jeff Deverett 30:47

Okay, but the reason is, is because the filmmaker has not done a good deal for themselves. That's the reason it's not that the distributor did their job, they did a good deal for themselves. The filmmaker just didn't know better.

Alex Ferrari 30:58

It's okay. So So you were saying that they they are in the business to make money? And that's no question. And they are in the business to acquire films that can generate them revenue, no question. But a lot of times, it's you know, there's certain distributors out there that release 40 5060 movies a month, they're obviously not spending marketing money on all those films, they're obviously not spending, they don't have the manpower to, to focus their energy on on per film situations. Like there's like look a 24, which is you know, basically the Sundance of independence and distribution. Like, they pick 1112 movies a year. That's it. And, and neon, another one, like these kind of, you know, vertical, there's a handful these guys that just pick, they're, they're very selective with the kind of films that they pick out and base and they actually give it love and they actually push it and they actually like put the whole company behind it. But some of these shops they're just spitting out movies so off so much as a volume play, which is like acquire as many films as I can, it's and put them all into my library, and then try to sell them off to a streaming platform as a package deal. Were so there they just acquire acquire, acquire acquire for as long as I can keep them on the books, which makes me look better because my library is bigger and I look more attractive to to the new streaming platforms or or cable stations or whatever areas, but that necessarily means that they're going to do anything for them. So the value a lot of times and please correct me if I'm wrong. A lot of times the value is in the number of films that are halfway decent because there's a there's distributions that the distributors that will take anything, anything yeah, anything adjust to fill up their their library and sell sell like 20 crappy horror movies as a package deal to, you know, South Korea, and and they make three grand off that and that in the filmmakers will never make any, any money. So that, but if they try to sell that one film out of that 20 they'll never make it. Does that make sense? Am I wrong? All

Jeff Deverett 33:00

right. You're partially right person, right? I'm going to defend their honor. Okay. But that's fine. Okay, so here's the thing. They Yeah, there are there are companies that do that, and that's their business model. But you're the filmmaker, you own the movie, it's your responsibility to make the right deal for you. It's they're not forcing you into anything. You're walking in their front door, you're saying, hey, let me interview you. Let's see if you're the right fit for this movie. And now let's see if we can make the right deal. The problem is the deals are bad. That's the problem. So I'd like to talk spend a little bit of time talking about that, if you don't mind, please. So these are not evil distributors, because what you just described, the all you have to do is ask all you have to do if you need to know the asset. Like if you don't want to be put in a package with 20 other films for that month, you need to say, Hey, guys, how many films you you know, do you acquire a month or release a month? And, you know, do you package these things? But you got to ask those questions like you would in any business. So fears fear, if you ask the questions. Now, if they lie to you, they're bad people. Okay. But chances are, nobody's asked the question. So they're not even lying. They're not offering that information up there. That, you know, they might be omitting it. But But you didn't ask. So you got to ask the right questions. Alright, let me give you let me tell you what happens is, this is what I I've taken some filmmakers to these kind of meetings. I mean, I generally do it from my own meetings. But this is my favorite kind of distribution meeting. And some of it is me messing around and just having fun. So I go to a distributor. And for those distributors who are listening to this, some of you actually may have been in these meetings with me where I've done this Okay, so the first thing I say is guys, the reason I'm here is because this is a third party independent distributor if I want to if I'm looking for a deal for one of my movies, right, okay. I generally self distribute now, but did you know sometimes you know, there are situations where I'll still do that for foreign or something like that. So, first thing is guys, are you guys good at what you do? The answer is I'm going to paraphrase I get I'm just going to go quickly. You know? Hey, how you doing? Are you guys good at what you do? Jeff? We are the best in the business. Okay, we are the the one thing that you can be sure that it will be consistent with every single Film Company distribution company go to they were all tell you were the best in the business. Sure if they say they're the best, but we are the best, obviously, obviously. Okay, that's wonderful. I want to be dealing with the best. So I'm at the best. That's fantastic. Okay. Now, you've watched my movie, hopefully or the trailer or something like that, at least maybe. Is this a good fit for? You know, Jeff, we wouldn't be talking you wouldn't be sitting there right now if this wasn't the right fit for us. Okay. So you're the best and my movie can fit into your plan into your, you know, offerings. Yeah. Okay. All right. Okay, so we're through that. Let's, let's get to the next thing. Alright. Guys, give me just sort of an idea, an estimate as to what you'll sell, what's the gross revenue? And this is obviously way more detailed conversation because we're talking you know, different windows and television, you know, Home Entertainment, you know, digital, obviously, all this kind of stuff. Just over the next say, year when you release this movie. What give me a ballpark figure. And this is, you know, this is what distribution companies do and projections. Yeah, give me projections. What do you think it'll do? This is always the first answer. Well, Jeff, you know, it's hard to it's hard to say for sure. We it's we don't know for sure. It's

Alex Ferrari 36:34

the marketplace is changing.

Jeff Deverett 36:36

Yeah, the marketplace. Exactly. All that stuff. I say okay, guys. You just told me you're the best at the business. Oh, by the way, the other thing is, like, you've really how long you've been in business? Oh, 1215 years? How many films are released? 500. And how many of you made money with 490? Oh, so you guys really know what you're doing? You really, really know what you're doing? Okay. Give me a forecast. Well, we can't really give you a forecast. Because we're not sure what's going to happen. Why didn't you just say you, you released 500 films and you made money with 490? You must kind of know that you're the best in the business, you must be able to give me a forecast. Otherwise, how would you be in business? And how would you be so successful? Okay, you're right. Here's the forecast. We're gonna do, and I'm just gonna make up a number here. We're gonna do $2 million in sales in the first year after release this and here's how it works. ba ba, ba, ba Ba, it's a ballpark. They always say, you know, what you have, we're actually probably going to do 4 million, but we need to be conservative. Always say that. Yeah. You know, because we were probably going to double what we say but

Alex Ferrari 37:37

at least at least, but let's say we're going to do two, and occasional. And occasionally they'll go and there was another film that we had that was just like yours that did 5 million, but I don't want to get you excited. I don't want to get too hyped up. I

Jeff Deverett 37:48

don't want to get too excited. I don't want to get too excited. Okay. Okay. So I say, okay, so you're pretty confident about that. And you kind of just whispered in my ear that you're going to do 4 million, so 2 million is pretty conservative. Right? Can I like, can we use that as the number? Yep. Okay, now you're gonna and now we're going to just talk about which we can get into details about this later, Alex, but the terms and the conditions, but ultimately, how much of that money am I going to see? Well, you know, Jeff, we're not sure. Okay, till I get, let's get through here that you're the best. Okay, you're between your costs, your fees sub distribution, this that, that it added up? Do you think it's fair to say I'm going to get 50% of that money? Yeah, 50%, you should get a lot more, you should probably get to 60 65%. But let's go with 50 just to be on the safe side, just so we don't set your expectation. Okay, so let's just do some simple math. So you said you're going to do conservatively $2 million in sales, and I'm going to get 50% that would be a million dollars. Correct? Right. Okay. Guys, I have an idea. How about a minimum guarantee? Because you guys, you know, you're really you're the best in the business. You've had all this experience. You've just given me a conservative estimate. What about a minimum guarantee? What about giving me a minimum guarantee? Well, you know, Jeff, we don't do that. We don't give minimum guarantees. I say like, Well, why wouldn't you like you just lowball me and your sales figures. You lowball me and my percentage. You have You're the best in the business and everything and you and you're you've released all these films that are similar, like you must be pretty confident. They said Well, what I mean you know, what would you want? And I said, I got an idea. How about this? You told me 2 million in sales, which is really 4 million. You told me 50% which is really 60% so we're down to a million. I got this like great, crazy idea just just to be super conservative like you guys. Give me half just half of what you think you are going to give me so you are going to return a million dollars to me, give me 500,000 upfront guarantee, which is half Jeff, are you what are your mind half of what We guys, why would I be out of my mind? Aren't you the guys who just told me that it should be a walk in the park slam dunk to do that? I'm looking for half of it. If I was my mind, I'd ask you for all of it. But I just want half of it. Well, you know, we can't do that. And I say, Why can't you do that? Well, what if we don't sell it? If you don't sell it, you know, then then you're not so good. Well, what if our numbers are wrong? Well, you but you do that the best. Your numbers are right. So okay, so that's the game that gets played

Alex Ferrari 40:30

now. Oh, my God, this is I've heard that I've been in those meetings. I've been in those meetings. It's fantastic. I was gonna say, hey, just give me 10% give me 100 grand. They're asked what a puckered either way, it doesn't matter if, if you want to say give me 10 grand, they're asking to puckered.

Jeff Deverett 40:44

Okay, so now Now I'm going to tell you Okay, so that's from the filmmakers point of view, right. So there's a reasonable ask, but you know, it's a little bit irritating for for distributors to go through. But now I'm going to put myself on the distributor side of that equation, okay. And I'm going to tell you what's going through their heads, okay. Their heads are, as that conversation is going on. This is what's going processing through a smart, sophisticated distributor knows the business. They're saying, Do we really need this guy's film? Like, that's number one? Do we need this bullshit? Do we need to talk to this guy? Like, is he wasting our time? We're gonna have 19 other films this month? Do we need to go through this with this guy? Like, how important is this movie? So let's say if it's not important, it's over. At that point, they don't need the hassle. They don't need to negotiate. It's over. But let's say, hey, the guy's got a pretty good movie, we could probably make some serious money off of it. Let's keep this conversation going. So so let's get past that. Okay. So then the second thing they're thinking is okay, the guy's asking some of the right questions, and he's being a bit cocky. And he's, you know, trying to move the needle here and there. But how much does he really no, like, we could put this guy into play, and we'll, we'll screw him royally, like I will. And I gotta tell you how that works afterwards. Okay. Do we really want to put them into play? If we do, we'll take his film. We'll give him we're not giving him half a million dollar guarantee, even though we love the film, and we really gonna make a lot of money with it. You know, we'll be able to I can read in his eyes will lowball this guy. It's a poker game, Alex. That's all it is. It's just a poker game. Sure. I'm going to call the guy's bluff. I'm going to I'm going to call not going to go all in. But so you know, we'll put 200,000 on the table. And he'll bite because he's anxious. And we'll get him back. At the end of the day, it's all going to come you'll

Alex Ferrari 42:30

never see that he'll never see another dime. Other Penny anyway. So what the heck, right? Let's just do that. And we know for sure. And we have a really, as a distributor, I'm like, we know this is already pre sold, we can go to this guy for 50,000. We can go that guy for 150,000 and go to that guy for another 2x. So we'll cover our will cover are not automatically so there's no good. There's no way a distributor is going to put money down unless they have an absolute 99.9% guarantee that they're going to get that money recouped. Is that fair?

Jeff Deverett 42:59

No, that's not fair. I mean, they'll they'll take a little bit of risk, but no, maybe 25% risk. Next up 99.9. Okay, all right.

Alex Ferrari 43:08

And most these days, it has to be a really it these days, they don't generally anyway, because it's just

Jeff Deverett 43:16

if they're if they're in love with your movie, and they think they can hit you know, make some serious money with it, you know, a little bit of it not not a ton. Not a ton. Maybe 20% at the most I don't know, you know, it's hard to pick that number. Everybody's different. Okay, but yeah, but they're not taking 100% risk, obviously, they know already, that they have some output deals that they have some you know, like, like you say preset, you know, revenue stream revenue. Yeah,

Alex Ferrari 43:39

they have relationships that they could call a bob over in Germany and Bob's gonna buy. Pretty cool.

Jeff Deverett 43:45

Yeah, yeah. So after you leave that meeting, they're going to make some phone calls, make sure that they're good to go. And, and then they're going to give you your money. But the other thing they know is that they're in first position on everything. So even if disaster strikes, it's gonna be pretty difficult for them to lose that money, because they've been so conservative with you. And I can do the math with you like,

Alex Ferrari 44:06

so. Can you stop one second, I just want to I want everyone to listen to this really quickly. You said something I want to just focus on for a second, you said that they're not going to take 100% of the risk. But the filmmaker is taking 100% risk signing with them, because they're not in control. Is that a fair statement?

Jeff Deverett 44:25

Oh, that that. Okay. That's the bottom line right there. Here's the thing. Here's how this works. Okay? a filmmaker, if you don't do pre sales, which we'll talk about afterwards, okay. You are by making a movie you're taking 100% risk was the entire budget because you don't know for sure you're gonna make any sales, you assume you are, you assume there's going to be an audience and you assume you're gonna get some revenue. But because you don't have anything pre sold, like, you know, pre negotiated, it's not a sure thing. So it's 100% risk that a filmmaker takes. Alright, we'll talk like I say we'll talk about how to mitigate that risk. I mean, there's obviously tax credits, and there's increased pre sales and revenue, okay? But without any of that stuff, you're taking 100% of the risk. Now you walk in the door of a distributor, and they say, we love this. Or let's say they see what I'm at a film festival, they watch it, and they say, we need this movie. Some of them will say, Hey, you know, let's just buy this movie outright and cover the guy like filmmaker, this happens still. tremely rarely,

Alex Ferrari 45:29

but it does happen.

Jeff Deverett 45:30

Yeah, they say, you know, what, we know darn well, because like everything we went through, we're the best we've experienced, we've done this Saturday, let's, let's pick up this movie. And we're going to need to take some risk, because if we don't, the next person is going to pick up this movie, because it's so good. And, you know, if we take some risk, we can hopefully make a lot of money with it. So they will take some risk, you know, for something that they're in love with, and they really believe in. It's generally not 100% a risk is not as much risk as the filmmaker took for using for indie films. But it could be, it could be more than that. You could make a film for you know, $2 million, they could pay it up for $4 million. And that, you know, that's obviously the anomaly and the filmmakers dream doesn't happen too often. Right. But you know, it could, alright, so that for the most part, they might be taking maximum 50% of the risk, you know, like picking up a $2 million film for for 1 million me, but

Alex Ferrari 46:24

and again, we're talking anomalies. We're talking about outliers.

Jeff Deverett 46:28

Yeah, outliers, I would say on average, you know, it's 10 1010. No,

Alex Ferrari 46:33

like, no 10 films a year 15. a year out of the out of like, you know, I don't know, maybe more than that. But at Sundance, and which is where something like that would happen or at South by or Toronto. That's rare. It's still rare, especially in today's world.

Jeff Deverett 46:47

Yes, it is. It is rare, it's gotten getting more rare. And there's, there's reasons for that, which, which I'd like to talk about also afterwards. So there's believe that's happening. Okay, but Okay, so you're right, so so they're not in the business of taking a lot of risk, unless they're really, really, really in love with the movie. And it's something about is super special, and they think they can make a ton of money with it. And now, it's not even that risky, because they kind of can make those phone calls quickly and say, Hey, or they have output deals, or they have something where they know that they can recoup some of that investment.

Alex Ferrari 47:20

Alright, so you were saying Okay, so now, so let's go back to where you were talking about as far as the deal was concerned. So from the distributors point of view. So now let's say we got the filmmaker on the hook. Okay, we got their film. Let's say that they barely covered the MG. And again, the MG is a rarity anyway, but let's say that they cover the MG. And that that's topped out, there's there's very little bit money, or they make maybe a little bit more money off the MG. How does the distributor in their mindset? Well, let's just ask the question, how are they going to get screwed? How are the filmmaker is going to get screwed in the deal? Like, what are those kind of little things? Now? I

Jeff Deverett 47:57

don't know if I've listened to quite a few of your podcasts. But I haven't heard this one yet. And I don't know if this is gonna be super boring. Do you mind if we little do a little bit of mathematics? Because

Alex Ferrari 48:07

I think everyone listening would like to do some mathematics.

Jeff Deverett 48:11

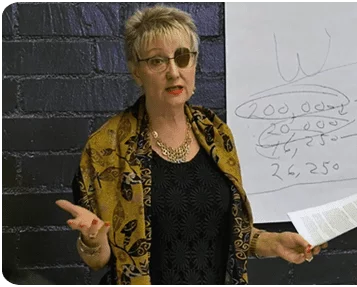

Explain how the math works. All right. Yeah. Here's our words. So, so let's just use Let's lose them a million dollar film. Let's do let's do a half a million dollar film. Okay. All right, just so we have round numbers, all right. And then of course, you know, we could extrapolate higher, lower or higher, okay, but let's just just so that we can throw some numbers around. All right. Okay, so you make a movie for a half a million dollars, that's your final cost everything in everything. All right. That's what you're on the hook for. Okay. Now, let's say that a, you give it to a distributor, and they go out and they generate a half a million dollars worth of revenue for the movie, okay? Now, that's what we call gross revenue. It's its raw, basic revenue that comes from the the customers that they're dealing with the the original customers, the people, the consumers. Alright, so in the case of, say, a theatrical release a consumer is, you know, a box, a person who goes and buys a ticket at the box office, that's a consumer. So when somebody spends, you know, $12 to go to a movie, or $15 that's considered gross revenue. $15 All right. Now, how much of that flows back to the filmmaker? So here's how the math works. All right. So put all that gross revenue into the so that would be like, let me give you some examples of gross revenue going to like what I just said go into the box office spending $15 on a movie ticket. Okay, going on to a streaming service renting for 499 That's great. That's $5 gross rental. Okay. In on the on the that's that's consumer on the buying a DVD 1099 or whatever. Okay? on the business side would be, you know, selling to a broad broadcast sale, you know, $50,000 or $100,000. For so this is all goes into the gross revenue pool. This is how much money was spent to buy consumers who are consuming that film. In the case of a television station, they're putting it up, obviously, on their station, and there's paying a license fee. Okay, so it's $500,000. So you, so a naive filmmaker will say, Well, I made my film for 500, and people spent 500. So therefore, it should be breakeven. Ah, there's obviously, yeah. Okay, so let's get down to the next level. All right, most of the distribution deals that you're going to do with a third party distributor, do not happen directly. So they'll go even the good, the really good companies will have half their, let's say, I'm going to give them you know, probably more benefit than I should have for their deals, they'll do directly, let's say, say on television, half of this TV licence deals, they'll sell directly to that TV broadcaster, the other half, they'll sell through sub distributors, whether it could be like foreign sales where they don't talk the language, or you have to do by law, you have to deal with a local company like in Italy, or something like that, where they encourage you or France, if you want to do a deal. And again, I'm just making up territories, but there are sales where it's makes more sense, or it's more viable to put it through a local sub distributor or agent. So those people are going to take a part of the pie. Alright, I'll go through the pie in a second. Okay, then, let's say you go through an aggregator which you have to do to go on to Apple TV, let's say or even,

Alex Ferrari 51:42

and distributors still have to pay, just like a filmmaker would have to pay.

Jeff Deverett 51:47

That is correct. There's only so many access points. So so they have to pay that too. So that's like using a third party distributor. So there's going to be a fee there. Okay. So ultimately, what we have to get down to is what we call net revenue, which is let's take all those third party sub distribution aggregator fees and take the end and look at the box office. I mean, I don't do a lot of theatrical I did one year in the theatrical distribution business. And you know, they have these film settlements, obviously, for gigantic studio films are different. But for indie films, the the theater, basically, that theater slash distributor is going to take 50% of the box offices, if you're lucky, if that's all they take, plus, you know, all your costs that are coming up to, but you know, like the film receipts from theatrical distribution, you're only going to see maximum 50% of them, you know, for an indie film, a studio, like I say, has the clout, they'll they'll get better deals. All right. So at the end of the day, basically, that $500,000 is going to get diluted down to about 275,000, you're going to see about 55% of it, on average, because there's going to be 30% distribution fees in sub distributors and 25%, platform fees and aggregator fees, and net, this net that Nick came

Alex Ferrari 53:08

up, but you never even talked about marketing, or or, or delivery costs.

Jeff Deverett 53:13

I'm getting there at a time. One thing, I get all the math figured out. I did this for 20 years. Let's not rush.

Alex Ferrari 53:23

Forgive me, sir. Forgive me continue.

Jeff Deverett 53:25

Okay, so you're that gross revenue that consumers spent like that the initial $500,000 of money that was collected in the sales of your movie will get netted down to about $275,000. All right, which will be what the pool is that you're going to share from alright. And and it could be you know, 300,003 25 like I'm netting it down. 45%. You know, that might be maybe high.

Alex Ferrari 53:55

Might be low. It could be low, actually.

Jeff Deverett 53:57

Oh, it could be low. Okay. I think it's, it's in the ballpark. Okay, so now now the pool is what we call net revenue is 275,000. net receipts. 275,000. All right. So now the distributor is going to take your third party distributor is going to generally take a 30% fee. I mean, you know, you can maybe negotiate a better deal, but let's just go with that. All right. So they're going to go 30% Now, here's, here's the first screw point. All right. This is where you can get royally royally, royally screwed. If you don't make the right deal and make sure the wording is correct. That 30% is that 30% off of the gross revenue that was originally you know, sold, or is it 30% off the net revenue. Now, as basic as that sounds like it should be off the net revenue because the receipts coming back to the distributor are is the 275,000 but they might say no, no No, we're taking 30% off the gross of the 500,000. I mean, that's a gigantic difference, right? It's $150,000, you know, 30% of 50. So that so that that is in a torturous way that sometimes this happens. Okay, it shouldn't. And that that I would say is immoral. Okay, it should off the 275. Right.

Alex Ferrari 55:23

But again, it's not that they mean to screw you. It just happens organically?

Jeff Deverett 55:27

Well, it's a good deal. Of course, of course, you know, and if you don't ask for it, like, you know, if you say, Hey, guys, where's this coming? Where's your feet coming off of, then? You know,

Alex Ferrari 55:39

it's Look, it's as if it will continue after this. It's the same thing if you go buy a car at a car dealership, and don't ask the right questions. If they're gonna, they're gonna charge you, they're gonna charge you for upkeep, they're gonna charge you for a maintenance fees, and like, you know, upgrade packages and all that stuff. Unless you say, ask the right questions. Same thing with the house, like your example, if you don't ask the right things, if you don't get an inspection of the house. And if you don't know the know, to get an inspection on the house, you could be buying a lemon, you could be buy something with a cracked Foundation, and you could lose your entire investment, you need to ask the right questions. It's not just like a realtor, just like a car dealer. They're not going to offer it up. That's unfortunately, business.

Jeff Deverett 56:21

Okay. But hopefully, that's the major, the first the major hurdle is make sure that the distribution fee is coming off the net revenue, not the gross revenue. Now, they might say, hey, some of it has to come off gross, because we did the sale, you know, as opposed to a third part, like, third party fees coming who's covering them and all that kind of stuff. So yeah, I could go into a lot of detail. This is a whole obviously a whole area. Right? Okay. So the next thing is the marketing costs, which, you know, you just asked me about. So let's say, Now, here's the thing about marketing costs. Alex, this is the interesting thing, we're filmmakers, you have to really think about this, okay? You want your distributor to spend money, because you want them to market your film, you actually want to encourage them to spend money so that people, they can create awareness for your film, so that you can actually they can increase the sales, you don't want them to not spend a lot there. Now, but what you do want them to spend is it, you want it to spend it wisely on the right things, and you don't want them to mark it up too much. So here's a perfect example. Okay, if you, you know, they'll they'll want to cut a trailer for you, you make, they're gonna want to cut a trailer, they're gonna charge you, you know, 30 to $40,000 to cut a trailer that you probably could have either cut yourself or negotiated, you know, three to $5,000 to cut the trailer because you know, comfortable. Yeah, but that, you know, fair's fair, you want them to do it for you, they're gonna they're gonna spend a lot more money doing it, because that's what,

Alex Ferrari 57:50

by the way, but their cost is about $3,000 to hire the editor in that area, their in house editor. Look, I've been I was imposed for 25 years. So I know what I did many trailers. I know what the cost of a trailer is from I you know, and I know what high end trailer editors make. Even on the low end trailer editor, there's no way to 30 $40,000 it's

Jeff Deverett 58:10

just not it's just, it could be that they say we hired it out to a, you know, high end trailer company or, you know, they charge 20. And we're taking another 10 for managing it and blah, blah, blah. That's good management. Okay, but but that's how it works. Sure, sure. Okay. But you know, all you got to do to prevent that is say, you know, how much you're spending? Where's the money going? You got it, you got to ask those questions here. It's fair to ask those questions. If you don't, you might not catch any of that stuff. All right. Then there's delivery costs, which are, you know, used to be there was physical delivery, there's mostly digital delivery now, you know, like, so. But there's still there's costs Pete there's processing, there's queue, seeing, there's all this kind of stuff that it's real. These costs are very real. They, but they also can get very marked up. Well, you gotta you got to be paying attention to the costs. All right. Okay. And then there is, you know, stuff that I call miscellaneous and sillery stuff

Alex Ferrari 59:08

there. Forget the poster to the posters, always a nice little place to mark up things as well.

Jeff Deverett 59:12

Yeah, for sure. Okay, then there's, you know, festival fees and, and market fees and all this kind of stuff, which so this is a new thing that has happened in the last say, decade with distributors, I've noticed that they're charging a flat fee. Like, I'm going to take you to Cannes or AFM or something and I'm going to charge you 70 $500 flat. That's your your fee to, you know, be part of my offering at the market place. It's questionable to you know, I mean, look at look, there's no question. It's super expensive to attend these markets. In Defense of the distributors. The booths are ridiculously costly. You got all these people traveling and all this kind of stuff. But, you know, like you say, some people have 20 films, some have 10, whatever, and, you know, they make money that way. That's a very good source of revenue to cut. Their costs and potentially market up also. And again, they're not necessarily evil, it's a business model. That's who they are and what they do. So by the time you're all said and done, and you take away those distribution fees that are coming off of hopefully, the net revenues and not the gross revenues, and the marketing costs are, let's call them 10%, let's call the delivery costs like three and a half percent, the festival fees two and a half percent, blah, blah, blah, you are down to 46%, the net revenue, which is 9% of the gross revenue that was generated, you're down to the $500,000 that was generated for your movie, you're gonna get 45,000, when all said and done, and again, I'd be happy to send you the math and show you how that I mean, I'm looking at a spreadsheet as I'm talking. Sure, you're gonna get $45,000 if the movie generates a $500,000 movie to get generates 500,000, and receipts, gross receipts. Now, if the $500,000 budget generates a million dollars in gross receipts, I can do the numbers a little differently. But in order to break even probably on a $500,000, you have to the gross receipts have to be about 1.1 or 1.2 million to get back the entire 500,000.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:23

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. So and, and my I love the numbers, I think the math is great. I think that you're being very optimistic in your projections in that there's not more costs involved as far as the

Jeff Deverett 1:01:49

revenue, but I'm talking about monitoring your costs. I mean, you look at you can say to a distributor, I want you to spend an extra $20,000, you know, on this market and buy some art, you know, some posters and some billboards and stuff, he's been billboards and all that kind of stuff, they may or may not do it, because that's a risk because they're putting that money up. But if, you know, if you're guaranteeing it, or they believe there's enough revenue or whatever, then they'll do it, but they'll deduct it, they'll charge you a little bit of a premium because you know, there's servicing and there is labor involved in doing all this kind of stuff. So you're right, they can spend a lot more I'm talking about monitoring it like saying, you know, reasonably speaking 10% you know, should should do it. But reasonably speaking,

Alex Ferrari 1:02:30

yeah, yeah. I mean, because I've seen I've seen breakdowns before on on some of these deals, and it just just like, it's it's abusive, it's abusive, it can it can get if you're not looking. It's like anything, man, if you're not watching the babysitter, with your baby. That's correct. Thanks. You know, all of a sudden, the baby's out in the street and get hit by a car. Like it there's, it happens if you're not keeping an eye on it all the time. Alright, so continue, continue,

Jeff Deverett 1:02:56

you got to pay attention. I mean, and, you know, like a lot of filmmakers, number one, don't know how to pay attention because they don't know what to ask. So fair, fair. And number two, it's kind of a pain in the neck to pay attention. Like it's it's a lot of attention. You know, I'm

Alex Ferrari 1:03:12

an artist, I don't want to think about

Jeff Deverett 1:03:14

exactly. You don't want to have to babysit this, like you're hiring a distributor to do a job, you want to trust them, they, you know, they're going to do a good job because they know what they're doing. You just want it to be fair, and honest. That's where you're this whole predatory distributor thing. Alex, you're talking about honesty, that's what you're really talking about, oh,

Alex Ferrari 1:03:32

it's a trust. It's absolute trust. But that's trust in any business deal, that when you sign an agreement with any kind of business across all industries, you're trusting the other person's going to do what they

Jeff Deverett 1:03:44

say. That's correct. Okay. And and and reported properly at the end. Now, this is assuming with the numbers I ran through that they all get reported properly. Oh, yeah. Some holes in the reporting to, obviously, thing so

Alex Ferrari 1:03:58

yeah. So so things can get a little gray in the sense of reporting, so they could, they could say, Oh, we got 500,000. And but we really only report back a little bit. And that's what's predatory. I'm not saying all distributors, and I've always been very clear about that saying, not all distributors are predatory. I just say most,

Jeff Deverett 1:04:16

but not all. But I think example I just gave you was like full reporting. Like, here's what really happened. This is how it all flowed blah, blah, blah. Okay. Yeah. You know, if somebody generated 500 in revenue, and only you know, showed 400 reports, you know, that that's a problem. That's illegal. Yeah. So that's very predatory. But I wasn't going there yet. Yeah, I mean, it happens. There's no question it happens. And you have to, you know, you also have to have recourse clauses in your contract, ie audit, yes, an arbitration. And I've gone down that route before and I found things and I could tell you stories. I don't want to implicate anybody, but it happens.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:56

So in my book, I actually learned my distribution book and residency entrepreneur. The distribution chapter. I used to have this the other day when we when we first start speaking here like Alex, you're you're absolutely right. Where you you get screwed by a distributor, you know that they're doing you try to audit them and they're like, no, then you sue them, you take them to court. And then at the end of this whole experience, they go, Oh are bad. Here's the money. Yeah, I made a mistake, I made a mistake.

Jeff Deverett 1:05:22

Sorry, you have a $50,000 legal fee that ate up your entire extra money that you found

Alex Ferrari 1:05:28

if and they know that and they know that and they know that. So they're like, Okay, well, let's like, let's, let's mitigate our risk here. So like, if we take 50 grand from this filmmaker, it's going to cost them 50 grand to fight us in court for it. So they're probably just gonna just not deal with us at that point, right? It's kind of like the olden days with the old car manufacturers. They're like, Oh, well, you know that one part is killing? How many people are going to die because of that part? And how much are we going to have to pay out and it's like, they didn't care about life. They were looking at it strictly as a business transaction. Like, well, if they kill only 1000 people, if those 1000 people sue us, how much can we have to spend? Oh, we'll have to spend 100 million. Well, how much will it cost to pull the things back off? What's going on? So 200 million? Oh, no. It just leave it out there. Okay. all due respect. You are a bit jaded. Oh, I'm absolutely jaded. Yeah, you're a bit jaded. And for good reason, for good reason. You've made me more jaded.

Jeff Deverett 1:06:23

Yeah. Fair enough. I'm not as jaded even though I deal with this. I'm, you know, in the weeds in the jungle every single day on this kind of stuff. I just feel comfortable knowing what to ask for know what to look for. So some of them in the sausage, but you know how to make a sauce Tell me, at least they're gonna say, Okay, this is where you're gonna get screwed. If you don't like it, don't sign the deal too bad. And you know,

Alex Ferrari 1:06:44

you're coming from it, you're coming from a perspective of knowledge, you're coming from the perspective of of experience, so you understand how the sausage is made? On the other side, the other side of the table. So it's a completely different perspective than 99.9% filmmakers have.

Jeff Deverett 1:07:04

I feel like I have a fair seat at the table. And I get to have a fair discussion. Right now. I don't necessarily, you know, get everything I asked for or, you know, and people say, if you don't like it too bad. That's that's the best we're offering it. But at least I feel like we've had a reasonable, fair discussion. And I have there's nothing that I haven't really thought up

Alex Ferrari 1:07:23

and have. And have you been sitting in those meetings with these distributors? And they just go? Yeah, yeah, we can't we can't work with you.

Jeff Deverett 1:07:29

Yeah, of course, absolutely. No, absent Listen, those, I just did the math, the major thing, the here's the major thing that like I would say, the highest priority in a film distribution agreement that you have to get, it would be what I call a performance clause. Like, you talk about these 15 year deals, I think that's not right. But a 15 year deals, not nuts, if they're performing. So what you really need is you need to say, you know, as long as you guys keep hitting these thresholds, these targets, and you're making this much money and returning it to me, then we can keep going. Or we can do auto renewals, like they know, let's do a three year deal with five auto renewals. Assuming you hit a target every year that we pre negotiate like here, you hit a million dollars this year, you know, 18, you know, 1.8 million next year that added and if you're hitting the targets, you want them? Absolutely, absolutely, that's the major, the major cause you want to put in is performance. Because if it's not working, primarily is not working for both sides. But if you don't put that you can't pull it. And it's an optional, like, I call these performance clauses, there are options that the filmmaker has. So you do this deal, let's say you do, say a three year deal, as opposed to a 15 year deal. And you say, okay, at the end of three years, or the end of two and a half years, if you have this much revenue generated and reported to me, and the check in hand, correct, then we you know, then the deal can automatically renew, if not, I have the option of pulling the D terminating the deal. Because, you know, you might want to get pretty close and you think they're doing good and you know, COVID heads and something changes and you know, you don't want it to automatically terminate. You give yourself an option. It's a reasonable thing to ask for.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:17

Do reasonable distributors generally say okay for that? I mean, why wouldn't a dish like if a distributor says no to that situation, to that op that that ask, shouldn't you just run away? Because obviously, you know,

Jeff Deverett 1:09:31

I'll tell you what, here's the thing. At the end of the day, the film business is a business like everything else. Alright. But let's just Can I just get down to sort of the core basic thing before I go to here when I go, okay, there's two reasons why an indie filmmaker should be an indie filmmaker. There are two reasons All right. Reason number one is because, well, there's actually three reasons one is, as you call it, you get the disease. You just get this the bug. bug is virus that you just need to do this in your life, you're not sure why but it's it's sexy, it's appealing, it's fun, it's a great industry, by the way, it's a lot of fun, enjoyed a lot project based, completely different changing all the time, very interactive, social, all there's so many elements of the film business that make it so attractive, right? So you get the bug, right. But the major reason you want to become an indie filmmaker and put yourself out there, and and kill yourself and put yourself at financial risk and do all this kind of stuff, is because you got a story to tell, like you generally want to tell the world a story, or you know, or case of a documentary send a very strong message that could potentially change the world, or become your legacy and you're making a contribution to the world. And you're doing it in a very fun art form that people can, can absorb and consume across the world. I mean, that's a very compelling reason to be a filmmaker is as it is to be an author, you know, or a musician. I mean, it's an artistic statement of a message. And so that's the main reason you should be a filmmaker. Alright? The second reason is, hopefully, you can make some money, like you can have a good life and making a good living from it. Alright, that's becoming you know, less and less as we know, it's more of a struggle to do that in the in the arts, all the arts, not just, you know, as you know, music, all this kind of stuff. So, but if you're going into the movie business, primarily, and only because you want to tell a story, and you're not worried about the money, then this is a whole different conversation. All right, that's an artistic conversation, and all we are going to talk about is how to best tell your story, at the most cost effective price. But if you're going in, because you actually want to hopefully, at least recoup your budget, or at least maybe make some money and make a living, you know, hopefully become rich, but but at least you know, have enough to make a living, then that's the discussion that I'm having here. All right, this is about, about making a lit becoming a career filmmaker and making a living at become at being a filmmaker, as opposed to just making a film and having your fun. And you know, whether it's a midlife crisis, something like that, and making this artistic statement for the world that you want to do, I'm talking about being a career filmmaker, where you make a living at it. So you have to be very smart. So you have to be in addition to a good artist who makes you know, good quality films, you have to be a savvy business person. Because it's the film business, the film is the art, the business is the business. So, so I'm talking about the whole business side. All right. So assuming that you want to monetize your movies and get your money back, you got to be pre thinking about a lot of this kind of stuff. All right, before you make your movies, as we know, as you talk about it a lot. And you know, you so when you said to me, you know, if a distributor says, Hey, I'm not interested in your movie or something like that, or I'm not going to give you the right deal. Do you walk away? It's a business decision. I mean, most people think that's an artistic decision. It's not artistic, the artistic decisions already been done, you've already made your movie. This is strictly a business decision. Right? Like I said, it's a poker game. Do you think you got a better hand? Do you think you're going to get a better card on the next you want to fold? Do you want to play, make the bed and try to get the next card? I mean, it's a business decision. So here's the thing about the business decision. I mean, you got it. Hopefully, hopefully, you're armed with all the right things in order to make a good decision. That's what I've been talking about. This whole podcast so far, is getting you up to the filmmakers, understanding the tools they need are the elements they have to understand in order to make the good decision. But sometimes it's a business decision is a risky decision, right? Like, show me a business where you make a decision, and it's not 100% Sure thing, there's always going to be an out like anything like, you know, I talk about real estate, like, you buy a house and you say, Hey, I'm buying the house for lifestyle, because I want to live there. But hopefully it's gonna appreciate in value. You don't know that, you know, you go through all the motions say, well, it's good neighborhood and good schools and good this and good that, in their opinion on the cost of living is going up. So therefore, in 10 years, my house will be worth this much. You don't know that for sure. You take a chance with that. You do know that you're buying a house that you can like to live in a that's the artistic there's,

Alex Ferrari 1:14:20

and there's value in there.

Jeff Deverett 1:14:21

Yeah, the emotional side. Absolutely. But the financial side, you taken a bit of a risk. So should you walk from a distribution to you should only walk if you believe that you're, you don't trust the person. It's a trust thing if you don't trust the other guy, walk, but if you believe that you're getting a little bit screwed on the deal. If you if it's still you've asked the right questions, and it's still within the range of reasonable might be the far end range, the very far end range. It might be worth taking that deal because remember, on their side, it's like okay, if the guy doesn't Take the deal. You know what, we got 50 other filmmakers lined up at the door? And do we really need this film is it going to really change our lives? Probably not. Because they're going to let you walk.

Alex Ferrari 1:15:11

So the with the analogy of the house, the big differences of taking a risk of the house is you do have an asset that can be sold regardless, there, that asset will be sold, maybe a little less before then you sold it maybe a little bit more, but you will make money back with a film. It could literally have zero value, like literally lose everything, like nobody will buy it. And there are films that are made like that all the time that are done, spent a million bucks on, and they make very, very little money with because of obvious reasons, artistic reasons, business decisions, and things like that. But I feel that if this is my just my personal opinion, if you let a performance clause out for a distributor, and it's a reasonable performance clause, whatever that performance causes, yes, it's reasonable. Yeah. And they say not we don't do that. That's a red flag to me. Now, mind you, if you have a three year deal, that's different. If it's a three year deal, it's a three year deal. I mean, performance clauses generally going to be a three year deal. It's not going to be a 12 month deal. Generally speaking with a performance Oh, no, no, not necessarily, nonetheless, sometimes. Alright, so Tommy?

Jeff Deverett 1:16:15