Today’s show is going to be EPIC. Our guest is Matthew Helderman, CEO, and Co-Founder of Buffalo 8 and the BondIt Company. Buffalo 8 operates seven core divisions: development, production, post-production, distribution, client management, marketing, and creative branding services with accolades from the Sundance, Berlin, Toronto, Tribeca, and SXSW festivals.

At Buffalo 8, Matthew is endlessly passionate about creative storytelling, media technology, and the business of entertainment in equal quotients; we are the fusion of entrepreneurial ethos and quality content creation with a unified ambition to provide first-class service. With a background rooted in media production, finance, and digital technology he leads the team of both businesses on a daily basis.

We get DEEP into the weeds on how to raise money for indie films, how to approach investors, what companies like him are looking for and so much more. I learn a ton for this conversation and I know you will as well. Get ready to have your mind blown.

Enjoy my conversation with Matthew Helderman.

Right-click here to download the MP3

Alex Ferrari 0:31

Today's guest is Matthew Helderman from Buffalo eight. Now Matt is the CEO and founder of Buffalo eight and bonded media capital. Now what Matthew does is he finances movies every year ever and not just small movies. He does big movies, he does independent films, he helps out with all sorts of different financing. It really was. I mean, I can't tell you the treasure trove of what you're about to listen to. It is a master class in finding money for movie how how movies are made behind the scenes, how financing is structured, what you need to do, how do you need to approach finance companies or even independent finance ears? or private money if you're trying to raise money for your independent film? I mean, I can't tell you how much I learned talking to Matt. He was just so forthcoming and told me like anything I asked, he answered. So I mean, seriously, get ready to take some notes, because this is an insane, epic interview with Matt. So please enjoy my conversation with Matt Helderman. I'd like to welcome the show, Matt Helderman. How you doing, man?

Matthew Helderman 3:17

I'm good. How are you?

Alex Ferrari 3:17

Good, my friend. Good. Thank you so much for spending the time and demystifying finance in the film business for us. So before we get into it, man, how did you get started in the business because it is a unique story. It's something about the New York Stock Exchange was in there somewhere along the line I read.

Matthew Helderman 3:34

Yeah, so so I grew up. I grew up back east in Connecticut families in the private equity in the hedge fund world. My dad had started with a group of partners a fund when he was about my age. And so grew up in and around that environment. And like you mentioned, I got to have some pretty cool internships both some some pretty well known hedge funds and private equity places as well as we're being a runner on the stock exchange when that was still a thing. And recognize that there were aspects of finance that I liked, and are aspects of that sort of level of business that I could ultimately where that industry was going was not really suited for what I want to do with my life and I loved love loved content growing up. But from an audience, Asian perspective more than from a filmmaking perspective. So I was obsessed with film history and filmmakers and film theory and in college got into European film and the history of cinema and cinema studies. And then in undergrad, I got inspired by this digital boom that was happening with the red camera technology and Final Cut beings are available to edit and export content from a MacBook Pro. And all of a sudden it really leveled the playing field of how you could make and distribute content. So I made a feature when I was an undergrad and came out to LA to sell that during my senior year, spring break. It was my first trip out to Los Angeles and sort of had the veil lifted on this huge industry. That's out here. With sales companies and agencies and distributors learn the business from the ground up. And so buffalo been launched that prior year to produce that picture. And we brought that business out here, right? We graduated and grew it and grew it and grew it, and built out the management side, the post production side, and then launch bonded into end of 2013, early 2014. And that momentum just snowball across both businesses. And it really is sort of taking the applications of finance, both corporate finance and single project financing, as well as a true love and an understanding of content. Because at Buffalo eight, we had produced more than 40 features before we even launched bond. And so we had a real understanding of the cash flow need and our understanding that the banks and certainly institutional finance years, like traditional hedge funds, weren't really able to support let's call it content below six $7 million, which is the vast majority of independent film. And so we built a business that could could support that content.

Alex Ferrari 6:03

Now, can you explain specifically cuz you do a lot, it sounds like you do a lot. So can you speak to the audience specifically, like what you do on a daily basis, and what you're kind of like what your job is, so they can have a better idea of what you do?

Matthew Helderman 6:16

Yeah, I wish that everyday, you had some form of, of consistency, but we do. On the financing side, we finance almost 60 single picture projects a year. And so that range that ranges from very small, low budget content, where we have a handful of companies that finance or that we finance that are producing television content, so half $1,000,000.02 million dollar, either episodic or TV movies, and they might do five or 10 of those a year. And then we have clients that are making really, I'd call the middle market independent films, the two to $4 million type budgets. And we're not only originating those deals and structuring those deals, but closing those deals, and the closings are very taxing. I like to joke that I had hair when I started these businesses. It's partially a joke, but it's also partially honest, which is the closings end up taking the majority of our time, we see across the slate, probably close to 1000 project submissions a year. And those are projects that have cast directors, and all on board, sales already executed a distributor in the domestic components sometimes already buttoned up. And we're just coming in and effectively acting as the financial support for those pictures. And so the regular day looks like sifting through a slog of active closings at any given time, we probably have four to six closings that are term sheet out or term sheet sign. Then you have obviously the active portfolio, which at any given time is about 40 pictures. So you're tracking what's going on with the pictures you funded. Where are they in the collection cycle? What are the issues that need to be worked through in the delivery process, a distributors rejecting delivery in this territory, news or pain, painstaking brutality, that that is managing a portfolio of that size. And then there's also the buffalo eight side, which is producing content. So you're checking in on projects, that different set of team members day to day than the bunded team? How are things going on the active productions will short form and long form. And then I think maybe you know as well, but it also owns ABS payroll. So 30 year old entertainment payroll company, which is processing payroll for 700 films a year, it's a team of about 3030 or so. So it's my job is checking in and basically putting out fires across each of those areas.

Alex Ferrari 8:38

It sounds intense, sir. It's very it sounds. I'm exhausted just just listening to you. I can only imagine what you're like. I always tell people when they asked him like, I have twin girls, I'm like, I'm 25 Look what they've done to me. You must be like, 15 Look what this business is done to you, sir. That's exactly right. I'm aging horribly right. Now, so I want I've always wondered about this, because making money in the film business is almost an oxymoron. In many ways, like jumbo shrimp or military intelligence is like many multiples, like it's very difficult to do. So I always understand like, Hey, we're gonna go get a bunch of dentists to throw in 100 grand and make a movie. That model I understand. And I understand on the studio side when they're dealing with financial institutions and hedge funds and those kind of situations because at the studios, we you live in a very weird place because you live in a independent, arguably low budget, though a lot of people think under 10 million isn't low budget, but it is in the grand scheme of what movies are made for. And you're able to do this successfully and you've been able to grow your business. You're not doing one or two movies a year you're doing 60 a year. So there has to be some sort of You know, I'm just curious on if I don't know how much you can talk about the financial world behind it. But like, how do you obviously you have a track record. So you know, banks are going to do it in institutions, hedge funds are going to trust you guys to be able to make these kind of, you know, financing choices. But I'm so fascinated about, you know, returns and what is expected. And because, you know, the film business is infamous for not making money, do you group them together with like, a group of 10 films, and they kind of the, you know, the bad ones, the good ones pay for the bad ones? How does it work specifically, in your side, your corner of the industry?

Matthew Helderman 10:38

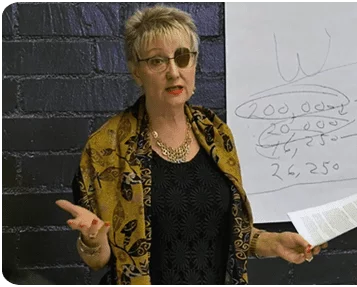

Yeah, I would actually say I'll answer the question by sort of painting a picture that is oftentimes most helpful whenever someone wants to have this discussion, which is, there are three models that effectively can work in, let's just call it independent studio world, which which I would say I know, folks who do million dollar movies, and they have great businesses doing that. And they're the folks that do sort of middle of the road, $5 million, then there's this nerve dolmen, and 7 million to $15 million, is a really hard place seven to 20 is a really hard place to make a movie, we can talk about that. But ultimately, there are three models that can work. There's the Megan Ellison model, right, your dad literally says, Here's 200 million bucks and go and you have basically a business model to say, Okay, I'm gonna lose money for seven to 10 years to build a brand to build a library and then the next seven to 10 years are hopefully making that money back and then some taking a long view on a library approach. that's never been our model. Very, very different business, then there's the business of Okay, let's come in and let you call it dentists and doctors, I would say there's definitely a sort of a single picture world where that 100% is a business. It's a really hard business. For producers. I don't think it's sustainable. I think it as an industry will continue to be a very real thing, right? There's gonna be 5500 feature films made this year globally, of that less than 10% are going to have any theatrical footprint at all. So the vast majority are either one of two things that are made for s VOD made for TV titles, or more likely, they're dentists, doctors throwing in capital that become sort of very expensive paperweights. And so we're not we're not really the Annapurna model, we're not really the dentist, Dr. model. And then there's a third model, which is you're effectively reverse engineering the content to fit the market, which is really what we've been able to capitalize on. And when you say we have a track record that we've done over 300, single picture financings, and we've lost money on less than four of them. And the reason is that we're not taking theatrical or why would even go further and colleges Commercial performance risk, which is a really tough business, I would go so far as to say it's a really bad business. Tell us about this. Yeah, and Unless Unless you have, and here's the thing, I mean, if I had 10 times the capital that we have been bonded, maybe like you're saying, you allocate some of it towards bigger trying to hit triples and runs, but funded today is you hit lots of doubles. And these are pieces of content that from a structural perspective, you know, the economics before you actually write the check, you know, what your return is, that your risk is really coming down to can the producers execute and deliver the film? Can the distributor that is signed up to buy the picture stay in business, which is a real risk in this environment? And can you do that enough times that you'll heavily outweigh any of the losses or issues that may may arise? And we've done it enough times to know there's always going to be bumps, there's always going to be challenges. But ultimately, again, we don't take I think about our portfolio, we've done 300 of these films. When bond in the early days, we were capitalized by investors that were backing the company that were backing single projects that were putting money into a farm. And we were lending that capital out against minimum guarantees, and pre sales and tax credits. And then about three years ago, we went out, we hired an investment bank to help us at that point, we had a track record, to help us go out and raise institutional money, which is insanely challenging. The administrative aspects of it reporting aspects of it on a go forward basis are mind numbing, it's equally as complex as filmmaking, except people don't want to hear excuses, and you've got to be even more on top of it. And we raised we raised capital from a very large institution that has been around for 40 years, and they provide capital to every asset class. So lending against construction, real estate and automotive, an invoice factoring. And they were able to really help us think about our business in a much more sophisticated way, especially because they can be very patient, right? They're public company. They've got $400 million balance sheets, a very different business than a film financier. And so when we got that deal done, then we were able to be a little more flexible, saying, today we have a dozen or so clients that are sales companies, distributors, animation houses visual effects companies that use bonded almost like a bank to smooth out their cash flows to finance their original productions, to borrow against their libraries. So all of a sudden, you're effectively peeking under the hood of hundreds of these businesses, whether it's on the ABS side, whether it's on the bonded side, that has allowed us to, I'm answering your question in a very roundabout way, understand through the financial dynamics of how so many of these companies are either working or not working, and then apply that when a new opportunity comes through the door.

Alex Ferrari 15:38

Very interesting. Now, in your in your experience, what is the biggest mistake filmmakers make when looking for financing? Because there are many?

Matthew Helderman 15:50

You can even write a book on it. Sure. I would say we have a number of filmmakers who reach out to us saying this isn't the next XYZ project. Yeah, it's just it's just wrong. And it's not to be arrogant or rude that maybe you could have written the greatest script in the world. Yeah. I won't, I won't say names, I'll just say, a top literary agent at the largest agency, most important agency in the world. We had lunch with them recently. And they said you could have the Best Screenplay in the whole world. And that one person gives a shit, you can actually make a decision anymore. They don't care. It has to be age based. It has to be cast as on directors on here's what the budget looks like. Here's the finance plan. Here's how we've mitigated by bringing in this number of sales. Here's how much capital has been raised to sort of hit this threshold. That's a good presentation. A bad presentation. Is this screenplays amazing, can you please have your team read it and get back to me in 48 hours, I need to go into production by this timeframe, because I have this actor who wants to do it. And his best friend is my best friend's cousin. And you hear that stuff 15 times a week. And you just know, those filmmakers are gonna have a really challenging time making that movie. And no matter how much you tell them, they still want you to get on a phone call. Just regurgitate, you can argue lead them to on our website that sort of guides them through, here's what you need, they'd rather get on a phone call and try and convince you that none of this is different. And I think that's the biggest mistake is believing that it itself is somehow going to convince someone like us would affect their institutional financier to take risks. And we see Angelina Jolie projects release their own projects, Edward Norton project doesn't matter, you still have to pass on it. If the deal doesn't make sense. We're not here to lose money. I'm not here to to have just credits. You I want to have a business that is sustainable and built for the long term. And I think filmmakers are so driven by making that movie. There's lots of producers, and I'm sure you know them too. They'll say anything, I get a deal. And it comes your job filter both the sort of two things, right. There's the passion of the filmmakers that hopefully they have good intentions from outset, when they believe the content is that good. So that's Mistake number one is not building the elements when they make that initial presentation. And then the second biggest mistake is just how much this industry attracts people that are scam artists. And I think what ends up happening ultimately, is you've got people that have good intentions, but the desperation of getting something made leads them to do bad things. And then once they've done that, once or twice, it's a lot easier to tell someone a half truth or a quarter truth than it is to actually be honest. And that's, that's a big part of our job is dealing with people that are talking out of one side of their mouth today and another tomorrow. And it's that's really challenging.

Alex Ferrari 18:41

I can only imagine what you have to deal with on a daily basis. The phone calls the meetings with people because I mean, at every level of the business, there's people who are trying to scam you, in many ways. Every every level from the screenwriter who's talking to a producer is like, Hey, kid, you know, sign this paper, and I'll option it. I'll you know, give me $1 and I'll option for 10 years. And now you've basically lost that screenplay just because, you know, there's multiple levels. But when you get to the world of money, and I've been in those meetings, and I've sat in those things, and I've meant, you know, you sometimes have dumb money, I've seen dumb money, like you know that will we'll write a million dollar check for a movie. Ever first time director, I've literally been in that room. I wasn't the director, unfortunately. But I've been in that room. So I can only imagine what you go through daily.

Matthew Helderman 19:37

It's crazy, which we tried to get better, especially over the years doing a few things, one being just listing out the exact criteria in a Frequently Asked Questions section and just directing people to this. So instead of them wanting or trying to get me on a phone call, or one of my team members on a phone call, it's guys you just have to follow this criteria and then we can really look at it and then we've also tried to get really better at there, there were days, certainly even as recently as the last few months where we've got 50 or 60 team meetings in a week that you're looking at new projects, or you're sorting out portfolio issues, and it's like, that's just not sustainable. You've got to figure out a better system to filter these projects, and also to deal with the projects when they have issues. So it's, it's definitely a continuing learning process.

Alex Ferrari 20:23

I can only imagine the egos that walk in those doors if you're sir. There is a lot I mean, how many how many? How many times have you had someone say, Well, this is going to win the Oscar

Matthew Helderman 20:34

So many times it's even better when when when the Oscars get announced like they did this morning and you've got people that are challenged say see by told you, my phone is exactly like this. It just got nominated for an Oscar and it's like, man, people will go to crazy lengths to justify why their deal is the best deal,

Alex Ferrari 20:53

Don't you love when you read a business plan? And it's like a horror movie, and then they bust out like paranormal activity. Blair Witch?

Matthew Helderman 21:01

Yeah, it's only blumhouse it's like, I'm basically just gonna make Jason blooms most successful movies.

Alex Ferrari 21:05

That's exactly everything's gonna hit exactly the way that's gonna happen. Correct. Or even worse, they'll bust out like things like, you know, easy writer. things up from the 70s in the 80s, that were independent, it's Yeah. You know, like, plan nine from outer space, man. And would he was on the I mean, look at that, how much money is that made? Over the years? Now, what are some of the biggest myths you you come across? Or would you like to dismiss regarding getting money for your independent, independent film? Because there are a lot of filmmakers have these ideas? Like many of the things we just were joking about, like, putting down examples of films like this is just like the matrix meets Marvel, like, dude, like you have it's in? It's a $50,000 budget, like, come on.

Matthew Helderman 21:54

Yeah. I would say? Yeah, yeah, definitely. I think I think there's a few of them. The first is, I'll just blanket it, which is what you've just said, which are people using comps that are not only irrelevant. It also goes into your your question about mistakes that filmmakers make, they haven't done the research to understand even the business they're trying to operate in, in the sense that a bloom is a perfect example, the number of people using vlaamse business model as a reference, he spent 10 years producing content independently with really close colleagues before he even had to deal with universal. He spent eight of those years negotiating that deal with universal, he negotiated a deal with universal that allows them to release these films on a studio level 1500 screen a minimum of the PMA commitment to be supported at 15 million or above on every picture, that cannot happen again. That way, someone will be as successful again, someone will do something and build an independent studio in a niche market again, but it won't happen that way. And so by saying, Oh, my movie is going to be paranormal activity. No, it's not because even movies that were successful two years ago, years ago, the movies that are going to look completely different because the models changing so much. I mean, Roma is a perfect example. That movie should by all file types and purposes, that movie should be financed by a single private investor, not a tech company, right? If you were trying to write the business model for Romo, you would not have written the model that ended up making the film successful. So it's dispelling the belief that what was successful will be successful, especially in today's age, where technology is changing how everything's happening in our business. And filmmakers just want to say, here are the numbers, here's the raw data. The second piece is going further into that raw data and saying, okay, so a movie makes $100 million. I don't think you understand how little of that actually goes back to the pool that you think it does, in the sense that you have so many costs in between the gross and the net, that you're not taking into account. And most producers we know don't even understand this, especially producers that are just trying to claim shot deals. And you're like he said, sell you on stats that are not truthful. That's the biggest myth is reading the Monday morning box office gross numbers and being having your jaw drop at some of the numbers because at the end of the day, cut it all in half. That's what comes back and then cut it all in half again after taxes and then hold that against the actual cost of a budget and see if it mattered, right? You've got off the top p&l costs, exhibitor costs, distributor costs, then you have the actual collection account costs, then you have latency because a lot of those costs are going to come in late so many of them are going to be written off as bad debt, then you've got to have it come back into the waterfall and you've got a senior lender on almost every movie before the equity even recoups then you've got the senior lenders premium before the equity that starts to recoup, then maybe mez, then maybe equity and then at that point, the equity has to start paying taxes. To what do you do again, an understanding of that waterfall to me is one of the biggest myths of What Hollywood has been able to really do a great job just like they do with the rest of their product, sell sexy story, as opposed to sell the honest reality of what the economic waterfall looks like. And really, art, film finance ears get this. And they, they, they use it to their advantage.

Alex Ferrari 25:18

But I think that's probably the biggest myth to me is boxoffice. Hollywood is very good at selling that sizzle, but not so much on the steak. Without question, so like, in that I want to talk touch a little bit about the box office myth, because, you know, people's like, oh, that movie made $800 million. Like, yeah, Mike, how much did it cost? How long did it take out that what's the Mark was the PNA budget that they had on it like, so movie like, justice? Like I always beat up Justice League because it deserves to be beat up. But, you know, movie like Justice League that cost upwards of over $200 million on a production standpoint, then at least 200 million on PNA. We would you agree with that. I mean, because it was everywhere, like you couldn't even move without seeing a poster for that damn thing. So now you have a $400 million plus budget, not to mention all the there's probably a bunch of other expenses. I didn't see the movie pulled in what 780 800 or something like that domestically, let's say. So if it pulled in $800 million, let's do your math. Cut it in half, then cut that in half. And it pretty much was a loss.

Matthew Helderman 26:28

Yeah. And I think what people often forget is taking the taking the gross number and applying it just to one set of economics isn't how it works. And I think the easiest way to think about this is why it's so important for a film to open up so well. We can one weekend to weekend three is that the exhibitor takes the lowest percentage of your gross in those three weekends. And even easier or set another way, as you think about the business of owning a movie theater, you're effectively a landlord, and you have a new tenant who's willing to come in each weekend and take that space and likely pay you more because more people are going to see it. So your split is going to be larger, you're going to make more money by bringing in new movies. So film that stay in theaters longer. Unless they're crushing it. They're just paying a larger percentage on a winding down tale of ticket revenues. So when you think about justice league, that movie, let's say it stayed in theaters for eight weeks. By week four, they are truly effectively at split with distribution costs, and x exhibitor costs. So now you're literally only able to justify staying in if the number of folks continuing to see the movie are outpacing the amount of economics that are being eaten away by the distributor exhibitor. Again, the collection costs, a lot of these theaters paid really, really late, and then they find every excuse in the world not to pay. So I think it's, there's so much more behind that. And just again, the box office numbers people are obsessed with. But that's not the whole story. For sure.

Alex Ferrari 28:01

What is in generally, I mean, I've heard different splits on opening weekends, I've heard a 3070. I've heard at 20, depending like I know, I remember when there's like big Marvel movies and like that is the ticket. We all know it's going to make a billion dollars and Disney will like flex its muscle like you want and it's going to be an 8020 for the first weekend, as opposed to the standard 7030 and then it just every week, you'll start glowing going down to 5050. Yeah. And how how low does that go? And in your experience,

Matthew Helderman 28:29

The lowest I've ever seen is 50-50

Alex Ferrari 28:31

50-50 is generally the lowest it'll go. But But at that point, though, yeah, it's not making it's just it's all because

Matthew Helderman 28:38

Yeah, the exhibitor doesn't have the same with you. That's a terrible tough business as well. But yeah, being the exhibitors don't have the same overhead structure. They've got their own issues to deal with, but they don't have. They also need to be recouping p&i, they also need to be recouping the actual production costs, they need to be recouping. Oftentimes, especially in those big pictures, there's huge bank loans that the interest is right and the film, The film is owned by the bank. And so that loan is paid off. The Disney is a different story Disney's effectively financing internally and then with JPMorgan. But that is a again, one of the biggest myths to me, is filmmakers not studying that understanding that and say, Okay, well then how do I how do I operate in this environment where maybe it's a better economic model to make a smaller picture that has a bigger footprint with international sales, a domestic distribution deal that might not even have a theatrical component is another one of the biggest mistakes we see filmmakers make is only wanting to make a movie if it has a theatrical footprint. That's just not justifiable anymore in the in the world we live in.

Alex Ferrari 29:45

Right and that is another thing that I love to talk to you about the theatrical because the I mean, look, theatrical is is the dream, especially for a certain generation. I'm not sure as much for the generation coming up behind us. That theatrical is going to be that big of a thing. But for us, we you know, we didn't have anything else when we were growing up. And theatrical is like the, the, you know, the the gold standard for you know, if you made it into a theater, you are a filmmaker. Right? We're now it's like you make it on Netflix, you're a filmmaker in many in many circles. What kind of you know, in your business model having, you know, budgets of 10 million? That's a 10 million and below, how important is the article? And where is the? Where are you looking for the revenue to come in from more than than not?

Matthew Helderman 30:33

It's not important to us at all. It's not that we dislike it. It's not that we dismiss deals that have either theatrical ambitions or a theatrical component built in by the time they reach us. And it's almost a certainty. What we do care about more than anything is who's selling the film internationally? Okay, what sales have they executed, both in which territories and to which buyers in those territories? And what does the domestic strategy look like more often than not, the domestic strategy is some form of the day and date with s VOD. And with theatrical maybe five to 10 City theatrical for certainly these middle market five to $10 million movies. But I think people again, miss the the rationale behind why that theatrical is often even happening, which is oftentimes it's only there as a tool to drive a Netflix deal. Now what I mean by that is Netflix has a structure in place with many distributors, that if they've opened up a film and X number of cities theatrically, Netflix takes it at a different level of their rate card. So Netflix has a rare card that is based on a number of things, and they've obviously massaged it over the years. But it can be based on percentage of box office gross, which was very famously for someone like relativity or even someone like Disney. So Netflix is literally paying X amount against box office gross, then there can be a structure in place that says if you as an independent distribution company have opened up a film in 15 to 20 of the major markets, we will take it for a million dollars guaranteed. That is usually the rationale on why distributors are playing the Xbox game, it's not knowing that they're not going to drive or attract and that much the economics from those theatrical markets, but ultimately that it's going to drive a better underlying s5 deal. So what bonded is doing is we're coming in and we're providing capital against in that example, just the Netflix piece, and whatever the guarantee was from the domestic distribution component in the other windows. So you're on the S VOD window, whether that's the utricle, whether it's traditional television pay cable, those windows, have assignable rates and assignable values and a great distributor and a good producer will pre sell those, or at least a portion of those, to make their film to not have to go out and try and beg borrow and steal from doctors and dentists. Some of the best producers we see don't raise any equity anymore. They make their films completely on negative pickup structures, using that kind of a model, where all of these windows are being pre monetized before they go into production. And I think that's going to become even a bigger piece where the business is going to go. And that's why we like the seat that we sit in, which is being selective, we'll say no to deals that we believe have too much risk, because we have a long term belief that film it content, whether that's now a television product that's being produced independently that we see a ton of whether it's digital content creators, and we have clients that are producing just content for YouTube, or Instagram, or Facebook, watch, the model is the same, those platforms are pre licensing, pre buying that content, and we're coming in and financing it, we have a very real belief that there's going to be more content. And I think probably you feel the same way, there's gonna be more content than ever before in the coming years, especially as you've got these huge players like Netflix, having these land grabs to acquire more and more so to us, the utricle is a nice component that can work for a certain kind of movie that I wouldn't want to I wouldn't want to bet on theatrical risk. And that's why we don't we don't do PNA we don't do to first out dance. The actor theatrical waterfall, we will secure against the theatrical waterfall, but only in the instances where we have the other windows as well as firm collateral because we just we see movies with projections that are incredibly aggressive and you look at them and say, oh, maybe this makes sense. And look, we've seen one of that and they have the exact names of the film. But you see Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt level movies. People are coming to us to ask you for PNA help or even production help from a financing standpoint. You take a hard look at it. You think okay, how is this going to do? If we had done those deals, you probably lose on half and make money on half but you break even at the end of the day. And those are probably two of the biggest movie stars in the world. So it's hard to justify the lower budget, theatrical play when the market even for the Iron Man talent is so volatile. And I'd even just say it's completely uncertain. It's a monkey throwing a dart with a blindfold. You just can't consistently pick winners if it's not possible.

Alex Ferrari 35:12

I mean, and that brings me to another question regards to star power. I mean, back in the olden days, stars meant some like really meant something like, you know, you put Bruce Willis Tom Cruise Brad Pitt, it's a guaranteed 20 million opening. It's a guaranteed 30 million opening. In today's world that's not the case at all. There's there's very few if I can't even even the rock you know, who's one of the biggest movie stars in the world? He guarantees certain amount but it's not like it used to be me. I remember when Tom Cruise opened the movie or Tom Hanks or or Brad Pitt or Will Smith, those those like it was an automatic people who just show up. We're in today's world. It's not that I mean, the only things that are generally winners every time are the Marvel movies. And they're very smart about how they do it. And even Disney, even Disney has their you know, long, Lone Ranger's. They're you know, john Carter from Mars, they have those occasionally, that they but they're so damn big. They could take those fibs orbit, they could absorb it and keep smiling. All they got to do is sell a couple more tickets to Disneyland. Alright, so what in your opinion like? Well, first of all, how do you guys at Buffalo eight actually assess projects for financing? I'm sure that's a question a lot of filmmakers like to know about.

Matthew Helderman 36:31

Yep. So I think what's most important is remember two completely different businesses, Buffalo eight is production post production management focus, okay, the only projects we're really looking for on that side are projects that can fit. And we have a nice overall relationship with places like Netflix and Amazon and Hulu, where we've done original content deals with them. Our goal going forward is almost exclusively to make content with s VOD platforms. It's much cleaner, when when it's a yes, it's a much safer and secure. Yes, it is with independent financing. Now, it's also the future. And I just am a huge believer. And we should just be putting all of our efforts behind building content specifically for these partners that we've built over the years. So the kind of content Buffalo, it's looking for package content. And that can be one of three things, or two or three of three things. And I think these are the underlying principles that will continue to drive this business, no matter what happens. And it's it, it's cast, or let's just call it more broadly, talent can be director can be writer, it can be cast, and it's IP. So it's IP capital. And I just, I'm a huge believer in that those are the three things, there has to be one of them, you either have to have some capital attached, the IP itself needs to be a huge meaningful piece of IP, by the time it comes to us, or you've got to have given you, you have to have one of those pieces assembled, it's too challenging otherwise, to move the ball up the field. And regardless, and we've had huge pieces of intellectual property, I mean, I'm talking Twilight Zone, I'm talking Spike Lee, I'm talking huge pieces. And it's still challenging. So buffalo eight looks exclusively for projects that have a piece that we can then move into and Shepherd into against sort of the esbat Arena abundant, we're looking at, I'll be very cut and dry first, and then I'll back it up with a little more empathy. We're, we're looking for projects that have SR collateral, it can be a tax credit, pre sales, it can be a bridge loan, it can be a negative pickup, it can be a media company looking to borrow against a library, it could be a media company looking to buy a buy another company, we're coming in and providing the capital for the acquisition. backing that out, obviously, we then care about the team involved, and the project to make sure that not only do we believe that the team can execute the project, but that the project isn't egregious. However, we want to apply that term. And also, again, is the element that we're calling collateral, actually secure the number of producers that will call and say, I've got this movie, I really want you guys to finance the tax credit, can we start closing and you look at it and say we don't have any other financing. There's no tax credit until the rest of your finances close, we'll have a filmmaker come to you and say, we've got all these pre sales want you to come in and do the pre sales loan, and you look at the company doing the pre sales and they've never sold the movie before in their life and they don't have a website. We're not doing we're not doing that. And then the number of filmmakers who say oh, I want you to come in and do a bridge loan and say, Okay, well, what am I bridging, you're bridging a guy that I met at a dinner party who said that he might want to finance my movie, that's not just called losing money. We won't be doing that. So it's, it's it's about assessing the package. And then once you actually have received the package assessing that the package is actually a verifiable opportunity versus a filmmaker again, likely being well intentioned, but just not being fully informed on what a company like us needs.

Alex Ferrari 39:56

Now, I want to ask you, what does a filmmaker need Legally to ask for money because there's so many not from you. But just as a general statement other than Look, if it's mom and dad giving you a check different, but if you're going outside of friends and family, what do you legally need to have to go out and raise money for a feature film in the US?

Matthew Helderman 40:18

Yeah. It's a good question. And like you said, it really depends how you're going out. And the terminal here is solicit. Now there are there are solicitation limitations. In regards to how you can go out and raise capital, you ultimately need a pretty, pretty serious document from from an attorney, if you're going out and trying to raise capital. That document it can take the form of five pages, it can take the form of we've seen 200 page.

Alex Ferrari 40:48

Is that is that a business plan? Or is that a ppm? What is that? Exactly?

Matthew Helderman 40:51

So yeah, it's a ppm but a ppm generally, what we see is now encompassing all of the aspects of the business plan.

Alex Ferrari 41:00

Can you tell Can you tell people what a ppm is?

Matthew Helderman 41:03

Yeah, it's a private placement memorandum. So it literally stands for going out and raising private capital. So you're you're soliciting an investor, whether that's an individual, whether it's a fund, whether it's a broker, and you're literally soliciting them to put a private placement into an entity, an LLC, or an inker Corp, whatever entity, you've set up to own the intellectual property and the underlying economic structure of the picture, the investor is buying a piece of that and to sell off security, which is ultimately what you're doing. You need to have your ducks in a row, because there there are many tripwires in regards to financial securities. So a ppm we see being the most often used tool, but I'd go and I'm sure you've seen the same thing to two sides of the market, really low budget producers, they just slingshot emails, dozens of them all over the place, every financier will get them on our buffalo emails, we'll get them in our body of emails, we'll get them in our abs. He knows like this filmmaker, this, this group is just slingshotting 15 episodes of spray and pray approach to raise money. That's probably not a good idea. I don't know many people getting movie science that way. So that's one side of the market where there's not a ton of organization. Then there's the high end of the market, where you've got the well known producers, I'll just get a phone call. And then you say, we just pre sold this for 10 million bucks, the Lions Gate. University is going to take the rest of the world for 5 million bucks, there's going to be a $1 million tax credit in Georgia despondent want to do it. You say Yeah. And then you get a finance plan that is sent via email, and you're off to the races. There's no ppm. There's no incredible documentation. It took those producers. It's kind of like that great story about Picasso dabbling on a napkin in a cafe towards the end of his life. And he was drawing and doodling and crumble the napkin up and get ready to throw it away. And a woman said, I want that napkin. And he said, Oh, I'll sell it to you. And she said, how much he said, $400,000? And she said, but it took 10 seconds makes it? No, it didn't, it took me 76 years in 10 seconds. And that's the same analogy I see with with high level producers is they are able to operate like that, because they navigated all the landmines of this business, and got to that position of being able to make a phone call and get a deal done. So the two polar opposite sides. And the reason I think we're willing to really play on both is, we have a lot of filmmakers that started on the lower side of the market that have now become really, really great producers, indie Spirit Award winners, producers that are climbing up the ladder to go do Golden Globe films. And we know that that has to be the way we think about investing in our business and investing in the community of earlier stage content creators that have to sort of get through again, that analogy of surviving the landmines of this business, but I would say hire a low cost entertainment attorney, it's a template document that they should be able to shoot out for you pretty quickly. And then just go out. And I think building that initial network of investors that believe in the filmmaker or the company, it's critical. It was what we spent the majority of our time doing is as we were building and I know it's not necessarily the most fun thing in the world, or glamorous, but it's the only way to build your real sustainable business.

Alex Ferrari 44:18

I mean, entertainment, they it's I find that filmmakers generally and I've met and spoken to 1000s of them over the course of my career, that a lot of them just don't want to do this kind of work. They just want to be artists. And they don't want to think about the business and they don't want to think about all the all the work that goes into building these relationships that you can literally just call up. Hey man, I'm just gonna call you up and I'm like, Hey, I got Yeah, pre sold this to Lionsgate for 10 million I got a 5 million let's let's make a deal. That took that took a while. I mean, you're not going to just accept that from anybody if I called you to said that. You were going to go Oh, wow, this is never made a $10 million movie. This doesn't make a lot of sense. Let me make a few phone calls to my Friends at Lions Gate at Universal, the sea, he's actually telling the truth. We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. But it takes time to build those kind of relationships up. And that's things that filmmakers don't get that this is a business. And I always I always use this line that I stole from a producer friend of mine, Suzanne Lyons that the word show in the word business, the word business has twice as many letters as the word show. And there's, there's a reason for that. Do you see? Do you see that as well, that they're just this people that just don't want? They want the quick, easy? They want that sizzle to Hollywood have sold them? But they're not willing to? To cook the steak?

Matthew Helderman 45:49

Yeah, yeah, no, of course, there's a not to use another quote. But if you're familiar with who Robert Mondavi is really famous wine maker in Napa, and towards the end of his life, they were basically reflecting on huge, crazy career, he built and launched effectively, an area of the United States into one of the most important wine industries in the world. And they asked him, he said, Well, it took a long time, he said, Well, it took a lifetime. But what else was I going to do? This is what I love. This is what I was always going to do here. And I think if you can think about filmmaking in that perspective, I think where I've always looked is, if you get the unfortunate reality of how the sausage is made with a lot of aspects of this business, and still love it, you're good, you can stick around. But otherwise, it'll it'll beat you up and tear you down, you have to be willing and able to put in a lot, a lot of hours outside of just being creative, the best producers and even the best creatives we know, they now invest time in some of the best directors we do, are now on closing costs. They're wanting to join and understand what's going on with the financials of this film, what's going on with how the finance ears are thinking about this project? What does that give me insight into the rest of the market? And I'm talking big filmmakers, right? The kind of folks that don't necessarily need to do that. But they're incredibly curious. And and I think that curiosity ends up just being a really big driving force.

Alex Ferrari 47:14

The more information you have, the more dangerous you are as a filmmaker, I always tell people, you know, you can have a conversation totally someone like yourself, and at the level, at least, or close to the level of what your expertise is. That opens up a lot of doors that would be close to filmmakers, in many ways. Would you agree with that?

Matthew Helderman 47:33

Totally agree. And I think from a finance ears perspective, or executive producers perspective, you have to be willing and able and wanting to do vice versa, right? You have to, we've made it a priority to go visit at least one set every single month. There oftentimes, there were years when we were building these companies where you have 30 movies in production in California at any given time. And you've got to be able to have that personal touch as well, it's in to know and I came up as a result from building buffalo eight and being on the ground building and making lower budget content, which is brutally challenging. From the seat of a PA to coordinator to production manager to line producer then getting pulled into a company that was producing a ton of international, freestyle driven content, trying to learn the business from if a producer calls me and says, hey, there's this issue, I get it, we've gone through it on the other side of the business and the buffalo 18 continues to go through it with projects we make. That to us is the biggest differentiator between the way we approach the market and almost anyone else is we've got sustainable long term capital. And we've got a team that likes and appreciates content, not only from an audience perspective and a creative perspective, but because we get how brutally hard it is to do it. And you've got to be willing and able to be flexible when you're a financier because of that, just like a filmmaker you like you said, should invest the time to learn some of the nuances. And even if it's just a cursory understanding of where the business is going, it'll inform you 1000 times better when you're out there trying to raise money.

Alex Ferrari 49:07

Now, I want to ask you about Netflix, and specifically because that is the the company of the day they are, they've come out and they've basically become a major studio in a short amount of time. I mean, they are bigger, and they're spending more money than most of the big major traditional studios in many ways. How have they changed the movie business landscape, in your opinion, in the sense of how business is done? I mean, they've they literally up ended this entire industry. But you want to see from your point of view, how do you feel that they've changed? Have they changed the game?

Matthew Helderman 49:47

Yeah, they changed the game in so many ways. And I would say there's a analogy that CIA has used multiple times which is Netflix is not, doesn't doesn't chain like an entertainment company. It iterates like a tech company. And so keeping up with the change of those iterations, when the tech company launches a piece of software, and then there's 2.1 and 2.2, they're literally updating the software for bugs. Bugs does that with their business model? And in an industry where things have operated pretty much the same way for hundreds of years. Yes, yes. So what a week See, I think the biggest and most obvious that is on everyone's telling us, they tapped into the reality that direct to consumer is the future. And it is the future now that really smart and agile companies like Disney, or unbeliev, unbelievably well run, arguably, more well run, we'll figure it out, we'll catch up, we'll build your own product. Netflix has a head start, no doubt about it. So I think direct to consumer that has changed a lot. We see a number of you know, even when maybe I'm sure you recall, when Uber came out, everyone in their mother was launching a business that was Uber of that Uber of eating Uber of walking dogs and car washes. So now you have everyone launching the Netflix of that

Alex Ferrari 51:04

we've got the Netflix of African American content, the Netflix of Christian content, the Netflix of children's content, and I have the Netflix of filmmaking content, you know, with irh TVs is a streaming service, right? Yes. And I position it that way. I'm like, I'm the Netflix does that something that everybody gets right away? When you say that?

Matthew Helderman 51:24

Correct. So we see a ton of those platforms popping up, which has led to great opportunity for us, because then we become the financing partner for I can't necessarily name the name of the company, as I'm sure you could research them to companies that are Netflix or African American content, and they've got 700,000 subscribers that pay 699 a month. That's a real business, oh, yeah, can you can find it, you can find some content, you can build a little platform, you can build a library and build a little studio. Same thing with the content. So that has been a big opportunity that this Netflix effect has created for us, then there are the sort of negative implications, which is the fact that Netflix expanded very quickly to 110 108, whatever the exact number is, international territories. When they did that, a lot of traditional, let's just call it second window, whether that's Home Entertainment, through pay cable free cable satellite video was up ended. And that up ending took on different forms. Because other areas of the world are just not as saturated yet, with Netflix, we're comfortable with Netflix. And they're certainly areas where they just don't have good enough internet connection to be saturated with Netflix as we do. And so we started to see a lot of these buyers in these areas, going out of business or having to merge or not pre being able to buy at the same level they did before or having to buy only an action movie starring Sylvester Stallone for X amount, that's all they could buy, because that's the only thing they knew guaranteed could work. So we again, we phrase it internally as a Netflix effect continuing to push out traditional second window, again, in many forms, pay pay cable TV, and cable and entertainment. Then you have the reality of the Netflix originals. Right. So now you're talking about the business model and direct to consumer the model being now plot as their model then expanding and pushing out a lot of these traditional buyers, which has changed the way filmmakers can pre sell content, it has changed the ways that finance ears can bank certain content, like the UK used to be one of the most important territories in the world, like to the utricle distributors left on that entire country. So that's a huge change. And then you've got the implications of Netflix originals, which is crazy, crazy, because it changed so much over the last three or four years, which was they came up big at places like Sundance and Canon Berlin buying big splashy titles. And then they said, You know what? Screw it. We don't need to acquire anything. Let's just sign over all deals with the duplessis or sign an overall deal with Woody Allen at Amazon. And all of a sudden it became okay. They're just financing all this content and producing it primarily stage. And that changed the landscape for distributors. Do you think about someone like a two for a two four has had to be reactionary, and build that business climate when third party acquisition of titles isn't the way it was when Harvey Weinstein was around getting to go out and acquire unbelievably independently made movies that he might have had nothing to do in the development phase II two, four has to be heavily involved. And when we talked to them last week, we're going to do I think somewhere between 15 to 16 films, eight to 10 of them are going to be internally developed from script stage through theatrical release. So you've got to be able and willing to again take a very long view because you can't wait because Netflix is doing the same thing. They're corralling it from the script stage. And maybe even earlier, right Jordan Peele signing an overall deal. First, look, deal with Amazon, you have to be willing and able now to operate that landscape. So what are the implications? The implications are smaller distributors getting less optionality or having to pay higher dollars for big, splashy titles, and then they still need to still needs to work. You know, you think about neon, awesome, really cool. But they come out and they spend $10 million on assassination nation and the movie makes like a million and a half dollars, you have to imagine some of that was driven by a belief that Netflix was going to try and scoop it up, or 84 was going to scoop it up. And so now you're sidestepping landmines in a completely new way that you didn't have to two years ago, at Sundance or two years ago, it can. So I think Netflix is changing the business, obviously, I think, seeing anything revolutionary, they're changing the business at every single turn.

And they're, they're unbelievable. I mean, we've done Netflix original productions with them at Buffalo weed. And it's incredible. It is, again, in my opinion, it is absolutely the future of how a sustainable middle market Independent Film and Television company will live and thrive is by doing a deal with Netflix. And some of my closest friends in this business have said, we're doing everything, we can't just sign up for picture a year deal. And that will be our entire business, Netflix will finance all of them will build producer fees into that structure, we'll build our company overhead into that structure. And we're just producing content direct for Netflix. And those are some of the best and brightest and strongest companies in the entertainment business, basically turning their back on traditional theatrical and saying it's not the future, the future is Netflix.

Alex Ferrari 56:37

I mean, if you I just saw this Christmas that Kurt Russell movie, the Christmas movie that was directed by Chris, Chris Columbus. And I saw that I was like, This is the easily could have been released theatrically correct easily would have made hundreds of millions of dollars easily. But yet it was on Netflix. I was just like, Wow, that's a moment. Like, because it makes so many originals. It's like it's hard to keep track. But that's a that was a big budget original. You know, that was a big one. That was a big one. And I was and they I'm sure they did unsane amounts with that film. I'm sure. We're sure. And what do you think about Apple and all the other big players that might be coming into this space? How? How do you because Netflix has been the big boy for a while but you know, Disney? And then if Apple decides to throw its weight around, because it's got more money than anybody? Yeah, if they want to how do you think that's gonna affect this landscape and your business in general?

Matthew Helderman 57:36

I think it's good for our business, because a lot of that that product will still need to be financed. And a lot of the banks are already at their lending thresholds for Netflix and for Amazon. And so they actually tap us and say, Hey, you guys want to look at this because we're at our threshold. Now, which is great. I think why Netflix is so good. Compared to everyone else throwing their hat in the ring, is that they've identified the fact that their brand is many things to many people, whereas Apple is trying to be brand consistent. Hulu has tried to figure itself out as it's changed hands corporate ownership wise. YouTube Red is built for that we've gone into pitch content to them. And they say, Oh, this is good. But you have anything with Selena Gomez, and they're dead serious right? Now with audiences. And you think about Netflix, Netflix can be that right? It can release Taylor Swift's reputation, concert

Alex Ferrari 58:30

and Roma,

Matthew Helderman 58:32

Correct and Roma in the same same span. So to me, Netflix is bargain. They have by far the biggest moat built around their business. But how do what what do I think about? Obviously, Disney is the big one. It's Disney's big, big, big, big and Apple's definitely big. But Apple's also very measured, right? They're not going to come out and try and do what Netflix has done by launching the nobody with the crazy stat I'm in the film stats, kind of upsetting, which is only doing 44 Netflix originals between there's there's two departments at Netflix in terms of the original film team. There's the Ian brick and Matt Bromley team, which is doing sub $15 million movies. They're only making 44 reads this year. And then there's this scottsburg team is doing it's called Netflix studio. And they're doing the 40 million to $100 million movies and they're on track to do about 15 so total they're not even doing 60 movies, right and then you've got the TV side and they're gonna make 700 pieces of original television. Whether that's contained miniseries doc series, contained format, long format, you know, season two's etc. So TV is obviously a huge focus for them. And I think the stat that came out of their quarterly earnings call last year was 70 some odd I 74 75% of content that people are watching on Netflix is television. So for every hour, every 10 hours, you have seven and a half of that you spend watching Television. So I think the big companies will have an impact. Certainly there's an impact on Disney. And a lot of these, these people have finally recognized let's rip our content off of Netflix and not give them the keys to our car with without charging them a price.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:16

But they've already but they've already changed their business model. They've already they've already adjusted that like, Okay, take Disney say goodbye, do what you want to do. We've got 700 original pieces here, and we have one of the most valuable libraries in the planet. Correct. We did it in less than a decade. Correct. It's insane. It's absolutely insane. totally insane what they've done. But I think you're right, I think it is something that a tech company would have done. Because it's traditional Hollywood, they would have just never thought of it like they could not have seen it. So. And now. I want to ask a few questions. Ask all of my guests. What advice would you give a filmmaker wanting to break into the business today?

Matthew Helderman 1:00:57

Network like crazy lead on relationships like crazy in the sense of alumni networks, or family, friends, anyone that can get you a window into sitting down for lunch and meeting picking someone's brain. There's also great resources, understand and read the books in the history of this business. And then again, I think there's a was a rule of the early days of CIA. And we applied it and made it a rule here as we were building, which was someone on the team has to be at a event every single day, whether that event is a lunch or dinner, or an opening a screening a premiere, or an investor conference or whatever, someone has to be continually building their personal brand or a business's brand every single day for years. And we were doing that 567 years where you're attending something, what seemed like just a revolving door of events, but that becomes like you've mentioned, it becomes a Rolodex and a really, really strong Rolodex. So I'd say break in by leaning on people that can help you gain access to the business.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:57

Can you tell me what book had the biggest impact in your life or career?

Matthew Helderman 1:02:03

Yeah, I mean, I'll be like a cheesy teenager and say that early days, it's like Catcher in the Rye, of course, just being being high school kid. But then in terms of entertainment business, things like Easy Rider, raging bull crap rebels. Rebels on the back lot. But I would say most recently, the biggest books are probably the CIA book, powerhouse. That book has been definitely I love, love, love that book. A book called power house.

Alex Ferrari 1:02:32

Oh, that's going to be on my list. I don't even know about that book. That's the CIA. I've read I've read over it. I read over this bio back in the day, which was Yeah, fascinating. Facts. Excellent. And then also spikes. A spike Mike, slacker and dikes. Yeah, very good. That's another amazing of the glorious 90s glorious night, the glorious 90s, which many filmmakers still live in? And they think that that's going to be yes. We're all waiting for that El Mariachi check from Columbia. Yeah. We're all waiting for that. I made a $7,000 movie too. I don't understand why I didn't get the deal that Robert did What's wrong?Now what is the lesson that took you the longest to learn whether in the film business or in life? These are heavy, like Oprah style questions? I apologize.

Matthew Helderman 1:03:19

Yeah. Yeah, it's okay. I would say that that to me is probably a but I'm sure you can recognize I build these businesses very, very, very aggressively. Building up to the sort of track record we have in the timespan that we've done it in his requires your pedal to the metal. From day one, I would say, this year, I'm definitely I would say probably learned it towards the latter part of last year, being more reflective before being so reactionary, whereas when we were building it was you have to be reactionary all the time. That's just the pace at which you're moving and growing. Oh, it's now being more reflective, whether that's dealing with the growing team here, or the projects we're working on. But it at the end of the day, it's about taking a deep breath, and through the cheesy thing of counting to 10. before you're, whether it's responding to an email or dealing with a situation with a team member or an investor or as the portfolio got bigger and bigger and bigger, so too, does the stress. And you've got to be able to sort of say, Hey, sit down for all. And it's ultimately people and if you can deal with people well, usually being more restrained as I've gotten into my 30s. Now, trying to be more restrained. It's, it's definitely the thing that took me the longest and I was not willing or not wanting to be that person in my 20s. I wanted to be an absolute maniac,

Alex Ferrari 1:04:45

As you should be in your 20s. Now, the toughest question of all three of your favorite films of all time?

Matthew Helderman 1:04:54

I'm probably gonna go and use it very similarly to the book. question in terms of those that made the biggest impact No, no in order. I think the earliest big film for me is probably something like Apocalypse Now, mainly because I remember being like 12 years old, maybe even younger. And Francis Ford Coppola, or that 60s and 70s style filmmaking was the first introduction I had through my parents do really high level quality content that clearly was not made in through the traditional way. So I'd say that was huge. I don't even necessarily call it a favorite, I will call it one of the biggest life changing movies. The second would be, I was a freshman at a boarding school in Connecticut, and I had an unbelievably awesome English teacher who had just gotten out of college. And he had tremendous taste and the films that he introduced me to still to this day. I mean, I saw I saw Rushmore when I was 13 years old, and I've been a lifelong Westerners and obsessive ever since. Yes. So that was huge, definitely changed my life in a major way. And that was one of the first movies where I remember saying to that teacher at that time, like, I need to understand how this movie got made. who financed this?

Alex Ferrari 1:06:05

How does that work? What kind of what is this pitch? How do you pitch a film? Like?

Matthew Helderman 1:06:11

Correct? So I'd say Russian was probably my second. And then I would say that teacher definitely I won't even I won't necessarily reference him, you know, he turned me on to I guess it was awkward by then. A lot of painful so getting into it, obviously really breaking we'll European film, but I'm only a very long engagement in sort of the john Peters in that filmmaking. And then that got me into European film rights. film. Definitely. As I got older, Ingmar Bergman became like, yeah, especially in college, when I was studying film, philosophy and film history, scenes from a marriage totally changed my life, and just how, how talented you are as a filmmaker, basically, all you have is a room, a camera, and two actors and like four lights, and you're making a movie that is arguably one of the most powerful pieces of content ever. That was mind blowing. And I could go on and on. But I would say those three are probably the sort of end but then I got really into even around that time into what are the spielbergian history of it all? Of course, that's with Spielberg.

Alex Ferrari 1:07:16

Who wasn't? And if you're not, you're crazy. I mean, come on. And look, you can watch jaws right now. That movie was made in 77 and 76 forever, and, or 7576. And it's still holds. And not a lot of films in the 70s there's only you know, Scorsese stuff Spielberg Coppola. There's a handful of movies a hell hold and that's one of them. You know? Agreed. Watch Raiders of the Lost Ark today. Still still good. The fax still good. Now this last question, I'm gonna ask you, please be careful how you answer it. Where do you want people to find you? And how do they want you to find? Like, how do you want people that? Where can people find more about what you do? But do not give them personal information? I promise you you will be inundated.

Matthew Helderman 1:08:02

Yes. It's a bandit website, www.bonded.us. And there's a there's a application form there. If someone wanted to reach out with a specific project. It's just [email protected]. And then the buffalo wait website, buffalowaves.com. Abs, abspayroll.com. And we're all over social media as they think everyone our ages. So surely on Instagram, probably most active but Facebook and Twitter as well.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:31

Matt, Matthew, thank you so much, man. It has been an actually eye opening conversation with you. You've dropped an insane amount of knowledge bombs on the on the tribe today. And hopefully, we've helped a few people along the way today not to make some mistakes. Thanks, Matt.

Matthew Helderman 1:08:47

Very good. Of course.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:50

I want to thank Matt so so much for dropping some major, major knowledge bombs on the tribe today. And I am in that list. I learned so so much from doing this interview with him. And again, Matt, thank you so much for being so forthcoming. So open about the process, and really educating the tribe on how you actually get movies made, how you get money for those movies and how you should approach investors and so many other things we talked about. So if you want to get links to Matt, anything we talked about in this episode, please head over to indiefilmhustle.com/309 for the show notes. And guys, I know a lot of you are finishing your movies and you need close captioning, to put them on different SVOD, or TVOD or just deliverables to a distributor and you need closed captioning. So I am going to give you the tool that's going to save you hundreds of hundreds of dollars. It is called Rev. All you have to do is go to indiefilmhustle.com/rev. And you will get closed captioning done. professionally done for $1 a minute. That's right. It used to cost like $8 a minute to do just normal closed captioning, but now it's done. A minute, so just head over to indiefilmhustle.com/rev, and sign up and you get $10 off your very first order. And that's it for another episode of the indie film hustle podcast. As always, guys, keep that hustle going. Keep that dream alive and I'll talk to you soon.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

YOUTUBE VIDEO

LINKS

- Matthew Helderman – Official Site (Buffalo 8)

- Matthew Helderman – IMDB

- Matthew Helderman – LinkedIn

- Alex Ferrari’s Shooting for the Mob (Based on the Incredible True Story) Book- Buy It on Amazon

- Indie Film Hustle TV (Netflix for Filmmakers and Screenwriters)

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Filmmaking or Screenwriting Audiobook

- Rev.com – $1.25 Closed Captions for Indie Filmmakers – Rev ($10 Off Your First Order)