FIRST WORKS (1993-1998)

The old adage that “first impressions are everything” is especially true in the world of cinema. Chances are, if the first film an average moviegoer sees from a given director leaves a bad taste in his or her mouth, there won’t be much in the way of eagerness to see that director’s other work.

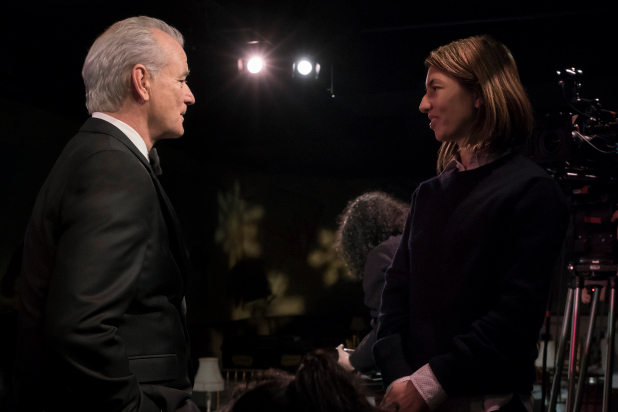

Some even take their criticism to a personal level, dismissing the director outright on terms of character and artistry. For instance, the first film I ever saw from director Sofia Coppola was 2003’s LOST IN TRANSLATION.

I was captivated by the quiet sensitivity of her characters and the evocative melancholy of the Tokyo setting, and as such, I’ve come to regard her as an accomplished filmmaker with a uniquely sensitive worldview worth expressing.

However, I know plenty of other people who saw the same movie and have written her off entirely as “boring”, “out of touch”, “over privileged”. As is the case with all forms of art, beauty is in the eye of beholder, and to my mind, Coppola’s films are all filled with an ethereal, ephemeral beauty and deftness of touch that’s exceedingly resonant in our increasingly-mechanized modern world.

The highest-profile and, perhaps, most serious, charge leveled against Coppola’s artistic character is the charge of nepotism. Nepotism courses through nearly every profession, naturally, but it’s an especially-visible phenomenon in Hollywood– after all, when you live in a town where a key barrier to success is “who you know”, having legendary New Hollywood auteur Francis Francis Ford Coppola as your father gets you a pretty serious leg up over the competition.

The film industry is full of such privileged and meagerly-talented royalty with which one could credibly argue for a case of actual nepotism, but the Coppola clan proves the exception to the rule. From immediate offspring like Sofia, Roman, and Gia, to extended family members like Nicholas Cage and Jason Schwartzman, visual artistry clearly runs through Coppola blood like a hereditary trait.

Sofia in particular has had a steeper uphill climb than the others– not only did she have to contend with charges of nepotism from an early age, she also had to overcome the inherent challenge of simply being a woman in an almost-exclusively male profession– indeed, she’s only the 3rd woman in Oscar history to be nominated for Best Director.

She’s never disavowed her admittedly privileged upbringing, which has given her an unique, well-traveled outlook on life that many find to be uncompelling at best, and hopelessly out of touch at worst. It’s easy to dismiss her work as a series of shoegazing portraits about the white leisure class, but look again, and you might see a biting self-awareness that adds layers of subtle nuance and humanizing depth.

Over the course of five features (as of this writing), Sofia Coppola has proven her bonafides as a director with her own distinct stamp, and has stepped out from under the overbearing shadow of her father’s legendary career to forge her own path.

Born in New York City on May 14th, 1971, Sofia Coppola was the youngest child of father Francis and mother Eleanor. She quickly earned her status as an artistic figurehead of Generation X by getting herself involved with film and fashion at an exceedingly early age.

She made her film debut only a year after her birth, standing in for Michael Corleone’s infant son during the iconic baptism scene in her father’s 1972 classic, THE GODFATHER. Her childhood was well-traveled, often accompanying her parents on Francis’ film shoots around the world– including a long stretch in the Philippines while her father was making APOCALYPSE NOW (1979).

In the 1980’s, she made efforts to cultivate an acting career by appearing in several of her father’s films from that decade: THE OUTSIDERS (1983), RUMBLE FISH (1983), THE COTTON CLUB (1984) and PEGGY SUE GOT MARRIED (1986).

She even appeared in Tim Burton’s 1984 short FRANKENWEENIE under the name “Domino”– a stage name she adopted for what she perceived to be its implications of glamor. At fifteen, she began exploring a lifelong interest with fashion by interning at Chanel (1).

1989 saw her professional writing debut, having collaborated with her father on the script for LIFE WITHOUT ZOE, a short film contained within the larger omnibus feature NEW YORK STORIES. Following her graduation from St. Helena High School in New York in 1989, she moved to Oakland, CA to attend Mills College.

After her disastrous, Razzie Award-winning supporting performance in THE GODFATHER PART III (1990), Coppola abandoned her budding acting career altogether in favor of one behind the camera. She would transfer to Cal Arts in Valencia before dropping out altogether to start a fashion line called “Milkfed” (which is still sold exclusively in Japan)(3).

WALT MINK: “SHINE” (1993)

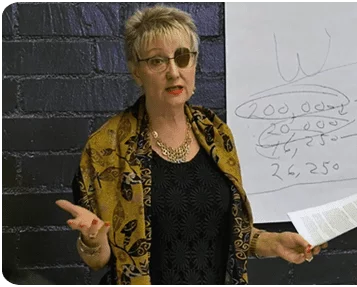

Coppola’s first official credit as a director is for a music video– a format that served as the entry point into the industry for many members of her generation. Created for Walt Mink’s track “SHINE” in 1993, the video marks the first appearance of several themes and images that would come to define Coppola’s distinct aesthetic.

“SHINE” seems to foreshadow the central approach Coppola would take for her 1999 debut feature, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES: a dreamy, shoegazing feel with a pastel color palette and a warm, summery setting. The piece is mostly shot as a conventional performance video, intercut with handheld footage of teenagers napping in the grass and swimming in the pool.

It’s obvious that Coppola is depicting a world she knows quite well– one of suburban privilege and leisure (that’s also exclusively white). Notably, the video was shot on the Coppola estate, and edited by filmmaker Spike Jonze, who Coppola would marry in 1999.

A simple concept with little structural shape to speak of, “SHINE” nonetheless hints at the artistic style Coppola would come to be known for: an observational and nostalgic gaze spiked with a punk edge.

THE FLAMING LIPS: “THIS HERE GIRAFFE” (1996)

Coppola’s second music video, for The Flaming Lips’ “THIS HERE GIRAFFE”, further embraces the rough-hewn punk inclinations of its predecessor. She again adopts a loose, cinema-verite approach that utilizes handheld photography to capture fleeting moments instead of staged setups, while embracing the imperfections of the format by keeping in light leaks and other filmic aberrations.

When combined with the punches of bright pastel colors dotting the otherwise monochromatic, blue-collar suburban environs, the overall effect reads as an avant-garde twist on the mundane. The video, which also delightfully features literal giraffes, further explores Coppola’s aesthetic interests in the iconography of suburbia as perceived by the teenage female.

A substantial amount of attention is paid to what is undoubtedly a girl’s bedroom– festooned with cats, rock band posters, and a plentiful splash of pink. Coppola’s unpolished technique echoes the rough, crunchy quality of the Flaming Lips’ track, making for an effortless match between sound and picture.

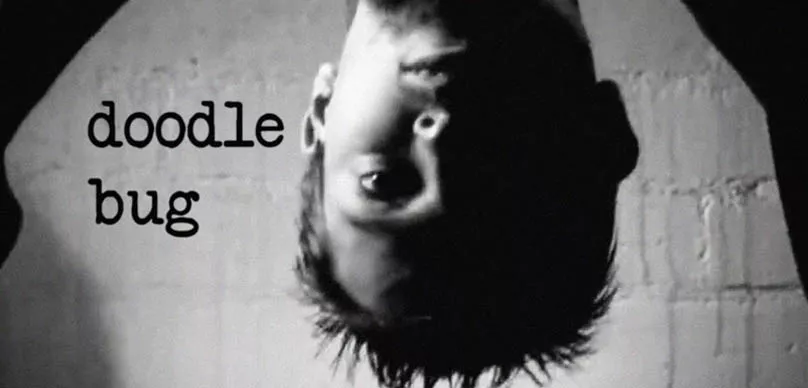

LICK THE STAR (1998)

At the age of twenty seven, Coppola made her narrative debut with the 1998 short film, LICK THE STAR. She wrote the script in collaboration with Stephanie Hayman, spinning a story about a clan of vicious teenage girls who hover obsessively around their queen bee while hatching a juvenile plot to poison the boys at their middle school.

Whereas most burgeoning filmmakers must make their first narrative efforts on a truly independent scale, her status as a second-generation Coppola filmmaker availed her of some admittedly enviable production resources.

LICK THE STAR was produced by Andrew Durham and Christopher Neil through Francis Ford Coppola’s production company American Zoetrope, as well as through her own directing representatives at Director’s Bureau. She even got such cinematic luminaries (and family friends) as Peter Bogdanovich and Zoe Cassavetes to make brief cameos as a principal and a PE teacher, respectively.

Despite these considerable helping hands, Coppola’s work on LICK THE STAR ultimately asserts itself, reinforcing the strength and competence of her own unique voice.

LICK THE STAR was shot on black and white 16mm film by cinematographer Lance Acord, who would go on to become a regular collaborator of Coppola’s on her feature work, in addition to the work of other directors in their wider social circle (Spike Jonze, Michel Gondry, etc.).

The decision to shoot in this format is undoubtedly an aesthetic one as opposed to a pragmatic necessity– Coppola’s handheld, observational approach effortlessly melds with the grainy monochromatic film stock and various needle drops from various garage bands like Free Kittens, The Amps, and The Go-Gos to create a tone that’s unequivocally punk rock.

The compositions are mostly functional and close-up, rather than deliberately artistic and cinematic. At the same time, however, Coppola punctuates her fairly straight-forward cinematography with impressionistic flourishes like languid slow-motion shots at key beats in the story.

While the rough-hewn cinematography may stand in stark contrast to the dreamy beauty of her feature work, the narrative themes on display in LICK THE STAR are part and parcel with her core aesthetic. The most obvious of these is the singularly feminine perspective, detailing the exploits of a squad of proto-Mean Girls who have managed to grip their entire school in a stranglehold.

They inflate the superficial dramas of middle school with life or death stakes, injecting a heavy dose of existential angst into the world of white suburban privilege. Coppola delicately walks the fine line between empathy and self-awareness, giving the plight of her characters serious weight while never losing sight of the larger social perspective– these girls aren’t inherently bad people, they’re just conditioned that way by the materialistic culture they were born into.

Their disaffected style of talking isn’t simply bad acting (although that may indeed be the case for some), it’s a deliberate decision employed to illustrate how complacency can lead to a severe detachment from reality and emotion.

Beneath its choppy surface layer, Coppola’s first short evidences a substantial degree of directorial promise and raw talent. It would go on to screen regularly on the Independent Film Channel, but has otherwise been little-seen by all but her most die-hard fans.

Nevertheless, LICK THE STAR accomplished its purpose of opening a path for Coppola to espouse her own distinct voice– one that has made American independent cinema all the richer.

THE VIRGIN SUICIDES (1999)

Some stories are so perfectly suited to a particular filmmaker that it’s inconceivable to think of anyone else sitting behind the camera. Director Sofia Coppola’s 1999 debut feature, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, is such a film: a stunning harmony of source matter and artistic vision that immediately announced her as a major new voice in American independent cinema.

The film was adapted by Coppola herself from the 1993 Jeffrey Eugenides novel of the same name, which spun the nostalgic and melancholy tale of five sisters blossoming into womanhood one fateful suburban summer, hidden away from the world by their overbearing but well-meaning parents.

At the sprightly young age of 27, the music video director / budding fashionista / art world socialite reportedly hadn’t yet considered a feature filmmaking career for herself, but when she was given a copy of “The Virgin Suicides” by her friend (and Sonic Youth frontman) Thurston Moore, she knew she had the perfect story with which to make her feature debut.

Undeterred by the fact the book was already in development elsewhere, she went against the advice of her father, esteemed 70’s auteur Francis Ford Coppola, and wrote her own script anyway. When she presented her draft to the rights holders, they agreed to make her version of the film instead of what they’d been developing on their own.

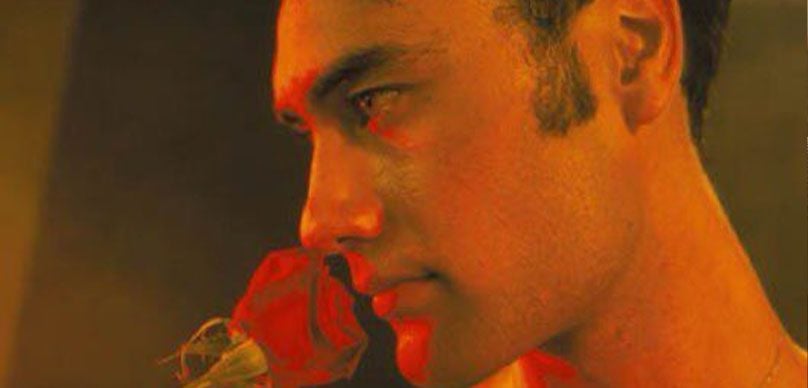

Soon enough, Coppola found herself in the suburban outskirts of Detroit, Michigan, shooting her first feature film with a budget of $6 million and the production oversight of her father’s company, American Zoetrope. THE VIRGIN SUICIDES is set firmly in the 1970’s, but the film’s perspective approaches the story from a point of hindsight, narrated in the present day by the curious neighborhood boys at the center of the film.

Now grown men with careers and family of their own, they can’t help but steal away to quiet corners whenever they’re back together, going over their old teenage obsession with the five Lisbon sisters who all took their own lives in a defiant act of rebellion against their strict parents.

James Woods and Kathleen Turner (who played Coppola’s older sister in father Francis’ 1986 feature PEGGY SUE GOT MARRIED) play Mr. and Mrs. Lisbon, an uptight religious couple who fear for their daughters’ collective chastity to the point that they are willing to seal them off almost entirely to the outside world.

As such, the five sisters– Bonnie (Chelsea Swain), Therese (Leslie Hayman), Cecilia (Hannah R. Hall), Mary (AJ Cook), and Lux (Kirsten Dunst)– have taken on an enigmatic, almost-ethereal air that captivates the neighborhood boys.

Their focus (and Coppola’s) converges on Lux in particular, played by Dunst with a flirty, knowing sensuality. This may be Coppola’s first film, but this isn’t the first time she’s worked with Dunst– the actress previously appeared in Francis Ford’s LIFE WITHOUT ZOE, a segment for the 1989 omnibus film NEW YORK STORIES that she co-wrote with Dad.

This particular summer coincides with Lux’s sexual awakening, sparked by a romance with the school stallion Trip Fontaine, played by a gangly Josh Hartnett in an aloof, cocksure performance. The revelation of this development causes a crackdown on the girls’ freedoms, leading to the mysterious group suicide that will captivate the neighborhood boys’ attention for the rest of their lives.

THE VIRGIN SUICIDES places an emphasis on its cast’s performances in lieu of sweeping turns of narrative, a challenge to which the members of Coppola’s cast ably meet– including short cameos from Danny DeVito as a psychiatrist and future Anakin Skywalker, Hayden Christensen, as a moody member of Trip’s football team.

Edward Lachmann’s cinematography ably evokes the summery, nostalgic vibe that Coppola aims for, and in the process helps to establish the foundations of Coppola’s signature aesthetic. Exterior scenes are lathered in warm, saturated tones, golden highlights and lens flares, while interiors are rendered with pops of bright color against the beige florals of white suburban domesticity.

Coppola and Lachmann manage to imprint a palpable sensuality on the 35mm film image, imbuing it with a soft, creamy texture not unlike sun-kissed skin. She frames the action primarily in wide, thoughtfully-considered compositions, making full use of the 1.85:1 frame while accentuating the potency of her closeups by virtue of their relative scarcity.

The camerawork adopts a classical, period-appropriate approach, utilizing dolly moves, locked-down one-offs, and languid traveling shots from the perspective of a car’s backseat (something of a signature shot within Coppola’s features).

Other aspects of the film, however, suggest more of an impressionistic, contemporary vibe– seen most visibly in the use of double exposures, 8mm home movie footage, timelapse photography, and even a present-day, documentary-style testimonial from a middle-aged, burned-out Trip Fontaine.

The most effective of these techniques is the staging of key conversations behind closed doors, reinforcing the film’s central themes of isolation and secrecy while subtly placing the audience in the same space of physical remove and unknowable speculation experienced by the male narrators. Production designer Jasna Stefanovic rounds out Coppola and Lachmann’s approach with scene dressing, props and costumes that authentically evoke a vintage 70’s, yet timeless, feel.

While Coppola might embrace a subdued application of period iconography, she uses the opportunity afforded by the film’s soundtrack to indulge in some iconic 70’s-era jams. Whereas other 70’s-set films like Paul Thomas Anderson’s BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997) embraced the glitzier disco aspects of the era, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES explores rock-and-roll’s contributions to the musical landscape.

Well known tracks like Electronic Light Orchestra’s “Strange Magic”, or Heart’s “Magic Man” and “Crazy On You” round out a suite of needle drops sourced from artists like Todd Rundgren, Al Green, and The Bee Gees.

French electronica band Air crafts a laid-back and melancholy mix of xylophones, beat kits, and other synthesized elements into an original cue called “Playground Love”, serving as the film’s de facto theme song while evoking the feel of a languid summer afternoon.

Like her generational peer Quentin Tarantino, Coppola isn’t afraid to abruptly silence a moment of non-diegetic music when she transitions to the next scene with a hard cut. The soundtrack works in perfect harmony with Coppola’s dreamy aesthetic, establishing her reputation as a filmmaker with a strong ear for sublime music.

The feminine mystique is a common concept present through Coppola’s work, perhaps none more so than in THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, which is literally drenched in it like humidity. The male narrators can’t seem to figure out what drives these enigmatic young women– their detached emotionality bears nothing in the way of clues or insight as to how they’re really feeling, which is why their dramatic group suicide comes as such a shock.

The artifacts of their lives– magazine clippings, records, hairbrushes, etc– become objects worthy of intense scrutiny and study. Their bedrooms become sacred shrines to girlhood. The process of puberty, of flowering into womanhood, is a magical, mysterious phenomenon to these boys.

The girls are fully aware of the mystery of their inner lives, evidenced early in the film by Cecilia’s response to a doctor who asks her why she would attempt something so drastic of suicide: “Obviously, Doctor, you’ve never been a thirteen year old girl.”

The quiet, observational femininity that drives Coppola’s worldview dovetails nicely with THE VIRGIN SUICIDES’ themes of teenage suburban angst. Like her approach to her 1998 short LICK THE STAR, Coppola walks the fine line between empathy for her characters and a wider perspective.

The reasons for the girls’ group suicide are ultimately trivial– a permanent solution to a temporary problem– but she never discounts the sincerity of the personal stakes that the girls have staked to their situation.

When hormones are running rampant, emotions have a life-or-death immediacy– a notion that’s amplified in a privileged suburban setting, where there’s the time and the luxury to dwell on heartbreak and despair, and true love is the only thing that money can’t buy.

The punk flare that also ran through LICK THE STAR surfaces throughout the VIRGIN SUICIDES, most visibly in the hand-drawn title treatments, which resemble the daydreaming doodles of a teenage girl’s school notebook. Behind the camera, Coppola also adopts her father’s tendency to mix work and family– recruiting her brother Roman as the 2nd Unit Director and bringing on Francis Ford as a producer and on-set source of sage advice.

Many directors’ first features are plagued by a variety of production difficulties and challenges, especially on the independent level. By most accounts, Coppola’s experience on THE VIRGIN SUICIDES was a relatively smooth one– she proved herself a hard worker and a confident visionary.

The biggest challenge she reportedly faced was a shortage of film stock, often hitting the allotted daily maximum by lunch. Her name and American Zoetrope’s backing may have played a part in securing a coveted slot at Cannes and Sundance, but the warm critical reviews made it quickly apparent that the film’s strengths were entirely a product of her own.

THE VIRGIN SUICIDES’ modest indie success proved that a talent for filmmaking ran in the family, establishing Coppola’s feature career with one of the best films of the 1990’s.

AIR MUSIC VIDEO, “PLAYGROUND LOVE” (2000)

With the 1999 debut of her first feature, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, director Sofia Coppola made a distinct splash in the world of independent longform narrative filmmaking. Like many of her generational peers, Coppola got her start in music videos, but unlike many of those some peers, she wouldn’t leave that world behind entirely once she’d made the big jump.

In 2000, Coppola released a promotional music video for THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, taking the film’s original theme song by French electronica band Air and turning it into a pop single in its own right. The resulting music video, “PLAYGROUND LOVE”, was easily integrated into the shooting schedule of THE VIRGIN SUICIDES by virtue of it simply re-using several prominent shots from the movie.

Presented in the square 1.37:1 aspect ratio, “PLAYGROUND LOVE” supplements the repurposed footage with new 35mm film shots that were captured on set, forming a vignette about a wad of gum being passed around the characters and locations seen in the film.

While the cue’s appearance in THE VIRGIN SUICIDES is purely instrumental, the music video incorporates vocals that are sung on-screen by the aforementioned wad of gum using subtle animation techniques. As the video unspools, Coppola spins a larger meta-narrative that breaks the fourth wall to reveal the production itself, even going so far as to incorporate herself in a cameo as the production’s director.

“PLAYGROUND LOVE” is a simple, clever concept that’s executed very well. The usage of chewing gum as a narrative device reflects Coppola’s thematic fascination with the teenage feminine mystique, what with its cultural connotations of emotional detachment, aloofness, and seductive allure crashing up against the trappings of adolescence.

Under Coppola’s subtle guidance, “PLAYGROUND LOVE” becomes more than just a standard-issue promotional piece; it’s a piece of art in its own right, further reinforcing Coppola’s undeniable appropriateness in adapting THE VIRGIN SUICIDES to the screen.

LOST IN TRANSLATION (2003)

I first saw director Sofia Coppola’s LOST IN TRANSLATION (2003) in college, and like several other films I saw at that time, the experience of watching had an immediate, profound effect on my own artistic development as a filmmaker.

I tried on certain aspects of the film’s stylistic sensibilities with my own work and found they suited me, but it wasn’t until my most recent viewing of the film for this essay that I became acutely aware of just how integral LOST IN TRANSLATION was to the backbone of my aesthetic.

As someone who spent a substantial portion of his early 20’s traveling back and forth across the country for college, the core of Coppola’s emotional message– the alienation of being a stranger in a strange land– resonated deeply with me.

Coppola too spent a great deal of her 20’s engaged in travel, although her status as the daughter of a wealthy film legend enabled her to voyage to farther-flung locales than people like me. She had a particular affection for the city of Tokyo, Japan, citing the city’s luxuriously labyrinthine Park Hyatt Hotel as one of her favorite places in the entire world (3).

That hotel would serve as the setting for LOST IN TRANSLATION, her second feature following 1999’s THE VIRGIN SUICIDES. Beginning with a series of short stories and personal impressions about the hotel and her experience in Tokyo, Coppola labored for six months to craft a screenplay about an understated love affair between a man nearing the end of his career and a woman just about to start hers– if she could only figure out what she actually wanted to do (4,5).

Coppola wrote the story with comedy icon Billy Murray in mind, even going so far as to leave hundreds of messages on the actor’s private voicemail box and enlisting her friend and fellow director Wes Anderson to make a personal overture (6).

Reportedly operating off of only a verbal agreement from Murray, Coppola and her producer Ross Katz risked $4 million in financing and untold professional humiliation, and moved to Tokyo to begin production without a firm contract from their lead actor. Much to their relief, Murray did show up on the first day of production, and as they say, the rest is history.

Much of LOST IN TRANSLATION may be predicated on the absurdities that arise from the culture clash between east and west, but in endeavoring to make a film about a brief moment of romantic connection rather than a conventional plot or story arc, Coppola had to create a sustained mood of subdued emotional tension.

The film’s storyline is the faintest of sketches: a quietly inquisitive newlywed named Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) travels to Tokyo on a business trip with her husband, but spends most of the time brooding alone in her hotel room. She’s coaxed out to experience the magic of the city by Murray’s Bob Harris, an aging, downwardly mobile American movie star who’s there to shoot a whiskey commercial.

During their various misadventures across the city, Bob and Charlotte develop a unique bond that allows them respite from their individual marital troubles. It’s easy to dismiss the film as a story where “nothing happens”, but to do so misses the point entirely– Coppola’s narrative is about those fleeting moments that make us see the world in a different way.

A glance, a brush of fingers, a barely audible whisper in the middle of a crowded plaza. It’s a film where every subtle interaction contains emotional magnitudes; the performances are the events. The chemistry between the melancholic Murray and the contemplative Johansson (only seventeen years old at the time of shooting) is as sublime as it is unconventional– the marriage of an old soul and a young heart.

While Wes Anderson’s films RUSHMORE (1998) and THE ROYAL TENENBAUMS (2001) foreshadowed the “Sad Bill Murray” persona, LOST IN TRANSLATION is the film that cemented it, fueling a late-career resurgence that would yield several similarly-sensitive performances that continue to this day.

Johansson’s work here put her on the map, paving the way to A-List stardom by acting as a fictional avatar for Coppola herself. The supporting characters further point to the personal nature of Coppola’s story, with Giovanni Ribisi’s busy, disengaged performance as Charlotte’s husband, John, allegedly serving as a veiled reference to Coppola’s own husband, director Spike Jonze (they would ultimately split later that year).

Anna Faris’ bubbly turn as the aggravatingly ditzy actress, Kelly, is generally considered to be a swipe at Cameron Diaz, who had worked with Jonze in his 1999 feature, BEING JOHN MALKOVICH. You’ll notice that all these familiar faces are almost exclusively white– a peculiar choice for a film set entirely in Tokyo.

While there are Japanese actors throughout, they exist almost exclusively in the periphery, confined by the bounds of their stereotype by The Anglo Gaze– a sore point of contention for the film’s many critics that lent ammunition to their argument for Coppola as an over-privileged rich kid with nothing meaningful to say.

While LOST IN TRANSLATION’s main cast may not be Japanese, the film’s approach to cinematography falls very much in line with the observational, interior nature of Japanese filmmaking espoused by such directors as Yasujiro Ozu. Lance Acord, who shot Coppola’s 1998 short LICK THE STAR, joined Coppola on her trek across the Pacific to serve as the film’s cinematographer.

LOST IN TRANSLATION’s visual style is simple, but deceptively so– every shot is deliberate and thoroughly considered, even in the haphazard-seeming documentary-style setups achieved via guerrilla filmmaking techniques in stolen, uncontrolled locations.

Because the cinematography is so minimal, every composition and the action contained within it has a specific narrative purpose. This begins with Coppola’s choice to shoot on 35mm film stock for its organic, romantic qualities– despite her father and executive producer Francis Ford Coppola’s insistence that she shoot on high definition video because it was “the future” (5).

Sofia and Acord draw a marked distinction between the tranquil, refined Tokyo contained within the Park Hyatt and the buzzing urban sprawl just beyond its walls. The hotel scenes are often locked off into wide, observational compositions with a shallow focus that throws the surrounding city lights into the shape of glowing incandescent orbs floating in a sea of black.

Bob and Charlotte’s forays into the city are rendered in the aforementioned handheld, documentary-style photography– partly as a directorial decision, but also because the modest budget precluded Coppola from obtaining permits for every exterior locale she wanted to shoot in.

This meant keeping the crew to a minimum (a challenge compounded by the predominantly-Japanese crew’s linguistic barriers), but the effort results in a film that properly captures the vitality, vibrancy and unpredictability of urban life.

Despite this bifurcated approach, Coppola and Acord maintain a visual continuity by establishing a few visual constants like color, light, and compositional framing devices. Coppola’s Tokyo is a megalopolis rendered in dusky blue skies, imposing grey monoliths, and garish neons.

She and Acord routinely shun artificial film lights, using the soft ambient light of the surrounding city as much as possible– an approach that gives the nocturnal exteriors in particular a distinctly textured immediacy.

Many shots, especially those of the up-close variety, use transparent or translucent framing devices and abstractions– glass, reflections, prisms, lens flares, etc– to break up the image’s natural lines into smaller segments, evoking the emotional barriers between the characters while reinforcing a subtle thematic undercurrent about the compartmentalization of modern urban society.

This idea arguably informs the evolution of a unique shot that Coppola would claim as a personal signature, akin to generational peer Quentin Tarantino’s iconic “trunk shot”. This particular composition, which also pops in her later films, is captured from the back seat of a moving car.

THE VIRGIN SUICIDES contained an earlier iteration of this shot, assuming the characters’ POV looking out on the neighborhood as it rolled by. LOST IN TRANSLATION flips the angle by mounting the camera to the car’s exterior and peering in on her characters caught in a moment of lonely reverie.

They’re moving through the world, yet they are also removed from it– enclosed in an alienating bubble of glass and steel. Indeed, Bob and Charlotte can only truly connect with their surroundings once they engage it on foot.

LOST IN TRANSLATION’s musical landscape reflects the interior nature of Coppola’s story, sculpted by My Bloody Valentine frontman Kevin Shields using a variety of New Wave and Tokyo dream pop tracks. Just as Air had crafted an original song for use as the theme for THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, Shields contributes a downbeat shoegaze track named “City Girl” in addition to My Bloody Valentine’s iconic song “Sometimes”.

Also boasting contributions from Death In Vegas, Jesus and Mary Chain, and her current husband Thomas Mars’ band, Phoenix, the soundtrack is more reflective of Coppola’s personal tastes rather than the cultural setting of her story– nevertheless, the cumulative effect of the chosen tracks is a sublime experience that resonates in perfect harmony with the story’s emotional truths.

To this day, LOST IN TRANSLATION remains the prime example of Coppola’s distinct voice as an artist. The quiet, navel-gazing nature of her aesthetic is crystallized here in her treatment of a story that shows subtle growth through observation rather than direct conflict.

The air of detached emotionality and feminine mystique that pervades her filmography is embodied in Johansson’s performance as the disaffected and lonely Charlotte, often seen languishing in her hotel room in nothing but a t-shirt and panties.

The controversial opening shot is another example of this, imbuing the film with a lingering sensual charge as well as a youthful vulnerability by shooting Johansson’s butt in close-up while she sleeps– the contours of her shape just barely visible through her translucent underwear.

The emotionally distant protagonist (both Bob and Charlotte in this case) is a staple throughout Coppola’s filmography, but with LOST IN TRANSLATION she uses the archetype to begin another career-long thematic exploration: the malaise of privilege and the ennui of the entertainment industry.

Being a successful (albeit fading) movie star, Bob can have anything he wants. However, the materialism of his profession leaves him longing for a profound emotional connection that he can only find with a complete stranger in a foreign land.

Coppola’s upbringing as a member of one of Hollywood’s royal families gives her a unique “inside baseball” perspective that fundamentally informs LOST IN TRANSLATION, as well as later works like SOMEWHERE (2010), THE BLING RING (2013) and A VERY MURRAY CHRISTMAS (2015).

Just as much as it is about the cultural landscape of Tokyo, LOST IN TRANSLATION is also about the emptiness of commercial Hollywood. As such, the film is peppered with winking in-jokes to the film industry, like the aforementioned Anna Faris being a veiled jab at Cameron Diaz, or any one of Bob’s frustrating Suntory shoots.

The whirlwind shoot for LOST IN TRANSLATION spanned just 27 days– but in that short amount of time, Coppola managed to capture more emotional truth than three or four Hollywood films combined. This can be attributed in part to her encouragement of Murray and Johansson to deviate from her script and improvise– a technique that, funnily enough, would net her first Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

Coppola’s emphasis on improv would also result in perhaps the film’s most memorable and dissected moment– Bob’s inaudible whisper into Charlotte’s ear during their final embrace, just before a kiss that’s both anticlimactic and cathartic at the same time.

The dialogue is inaudible because it wasn’t planned for– it’s a fleeting, beautiful moment of improvisation on Murray’s part that fits perfectly into Coppola’s established tone while also conveying the novel idea that audiences aren’t always entitled to the complete bypassing of a character’s privacy.

While technically-oriented fans of the film have spent years analyzing the specific audio bite in a bid to parse out Bob’s exact words, we can’t know what he said with 100% certainty. That ambiguity, however, is the key to the film’s profound emotional resonance– occurring at a register just below our conscious awareness.

After premiering at Telluride, LOST IN TRANSLATION quickly accumulated a high regard amongst critics. Many felt the film’s sensitive, nonjudgmental approach to the otherwise-unsavory theme of infidelity represented a new wave in cinematic depictions of love.

Academic Marco Abel called it “postromance cinema”, a subgenre that offers up a negative view of love and sex while rejecting the romantic ideal of “soul mates” (2). The negative reviews (of which, admittedly, there were many), tended to fixate on Coppola’s treatment of Japanese culture from her “outside” (read: white) perspective, citing her depiction of Tokyo’s native inhabitants within stereotypical constructs as a patronizing choice that undermined her core message.

Ultimately, a film like LOST IN TRANSLATION is going to be polarizing– I personally know several people who hate it because “nothing happens”– and any given individual’s impression of the film is going to differ from the next.

By conventional metrics, however, LOST IN TRANSLATION was a success, scoring $120 million in worldwide box office receipts and four Oscar Nominations for Best Original Screenplay, Best Actor, Best Picture, and Coppola’s first nod for her direction.

With LOST IN TRANSLATION, Coppola fulfilled the promise she showed with THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, delivering an achingly beautiful portrait of longing and discovery while consolidating the formal aspects of her artistic aesthetic.

MUSIC VIDEOS (2003)

Shortly after the release of her second feature, 2003’s LOST IN TRANSLATION, director Sofia Coppola capitalized on her rising profile by directing two more music videos that would further reinforce her street cred as a tastemaking filmmaker associated with the “cool” of alternative musical acts.

KEVIN SHIELDS: “CITY GIRL” (2003)

Much like she did for “PLAYGROUND LOVE”, Air’s promotional single for THE VIRGIN SUICIDES (1999), Coppola repurposed the numerous reels of footage she shot on location in Tokyo for LOST IN TRANSLATION into a moody piece for Kevin Shield’s original contribution to the film’s soundtrack: “CITY GIRL”.

By mashing together outtakes, b-roll footage, and printed dailies, Coppola manages to shape the video into a loose narrative vignette about a young American woman (LOST IN TRANSLATION’s Scarlett Johansson) roaming the streets of Tokyo while caught up in an introspective reverie.

By nature, the video is inseparable from the feature it’s meant to accompany, but it nonetheless stands on its own as an effective example of Coppola’s artistic signature from the period. LOST IN TRANSLATION— and to a lesser extent, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES— boasts numerous documentary-style shots captured from (and looking in on) the back seat of a car, so it’s no surprise that “CITY GIRL” is comprised almost entirely of these setups.

As far as promotional music videos go, Coppola’s repurposing of filmed footage conveys the same kind of economical and minimalist approach that Coppola would cultivate in her later feature work.

THE WHITE STRIPES: “I JUST DON’T KNOW WHAT TO DO WITH MYSELF” (2003)

Throughout the 2000’s, alternative rock band The White Stripes managed to achieve a sizable cache in the minds of creative influencers, to the extent that frontman Jack White’s distinct approach to old-fashioned blues and garage rock came to define a large aspect of that decade’s particular character. Coppola directed the video for the band’s 2003 single, “I JUST DON’T KNOW WHAT TO DO WITH MYSELF”, turning an act of sexual objectification into a liberating rallying cry for third-wave feminism.

The concept for the video is very simple: supermodel Kate Moss aggressively pole dancing in lingerie for the entire length of the video. Coppola takes what would be an otherwise-leering and arguably misogynistic concept and executes it with the arresting flair of an edgy fashion film.

Her technical approach is as simple as the concept– she shoots on a square 1.33:1 canvas using high contrast monochromatic film, keeping the angles fairly static except for when she stylishly rocks the camera back and forth on its tripod hinges in sync with White’s percussive guitar riffs.

By juxtaposing Moss’ nearly-nude body in silhouette against a blank grey background, Coppola creates a look that focuses on the interplay between light and shadow. Whereas her previous explorations of the feminine mystique in THE VIRGIN SUICIDES and LOST IN TRANSLATION broached the idea from the perspective of chaste, youthful innocence, “I JUST DON’T KNOW WHAT TO DO WITH MYSELF” finds Coppola conveying the same idea in the decidedly-sexualized syntax of stripping.

In the absence of the dreaded Male Gaze, however, the video instead becomes a punk-rock celebration of the female form in motion. These two videos would constitute the last of Coppola’s output for a number of years– her next major work, MARIE ANTOINETTE, wouldn’t arrive until 2006.

Despite their relatively short length, these two music videos show Coppola’s subtle, but continued, growth as a director while effectively acting as the close of the first chapter in her celebrated career.

MARIE ANTOINETTE (2006)

The timing of this essay on director Sofia Coppola’s third feature, MARIE ANTOINETTE (2006), is curiously coincidental, considering that I first saw the film in college during its theatrical release with my friend, Scott Nye. Nye is now a well-regarded film critic and writer, and just last week he posted his own thoughts on the film.

The timing of both these essays is of course a funny coincidence, but perhaps it’s more telling of the lingering impression the film has made upon us. Ten years later, the climactic sequence where the furious rabble threaten to storm Versailles still fills me with the same abject dread I felt in the theater, striking right into the heart of an emotional center that’s not usually moved by stuffy Victorian costume dramas.

This power and sense of immediacy, I think, stems from the one of the most contested aspects of Coppola’s vision: her re-contextualization of the past in the pop-cultural parlance of our present. MARIE ANTOINETTE is one of those rare films that challenges the most deeply-held preconceptions about period storytelling, proving that a filmmaker doesn’t have to be a slave to the tiny details if he or she is still able to tap directly into the story’s emotional truth.

As Wikipedia would tell it, Coppola initially wanted to make MARIE ANTOINETTE after the success of her 1999 debut, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES. However, her relative inexperience as a filmmaker made for an unwieldy writing experience considering not just the sheer scope of the subject matter, but also all the various interpretations that 200+ years of historians have applied to the personal figure of the last Queen of France.

To overcome her writer’s block, Coppola set MARIE ANTOINETTE aside and started writing a small script about a love affair in Tokyo that would ultimately become 2003’s LOST IN TRANSLATION. The success of that film eventually gave Coppola both the inspiration and the artistic momentum to complete the script for MARIE ANTOINETTE, setting it up at father Francis Ford’s American Zoetrope studios as her third feature.

The third film in any given filmography typically finds most directors flexing their muscles and aiming high, and Coppola’s MARIE ANTOINETTE is no different. Armed with the confidence gained from her two previous successes, Coppola set out to tell at once both her most epic and her most intimate story yet, rendered in a stunning blend of candy-coated colors and sumptuous scenery.

One of the most impressive aspects of MARIE ANTOINETTE is that Coppola and her producing partner Ross Katz managed to obtain special permission from the French government to shoot entirely within the hallowed halls of Versailles Palace– a masterful producing coup the likes of which we’re likely never to see again.

The gilded seat of the French monarchy hasn’t changed very much since 1768, which gives MARIE ANTOINETTE an unrivaled authenticity and sense of place. The plot chronicles Marie Antoinette’s development from her arrival at Versailles as a fresh-faced Austrian princess betrothed to the young French prince, Louis XVI, to her eventual fall from power as the despised symbol of royal excess on the eve of the French Revolution.

In her second collaboration with Coppola, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES’ Kirsten Dunst fully embodies the flirty, fun-loving teenager who would grow up to be a dignified (if misunderstood) Queen. Her nuanced, sympathetic performance reinforces Coppola’s attempts to humanize a historical figure we only know from old oil paintings hung in stuffy museums while drawing a direct line to contemporary socialites like Paris Hilton or Kim Kardashian.

The first act of the film finds Marie Antoinette adjusting to life as a French royal, which apparently involves consuming an endless series of decadent luxuries. She fulfills her initial duties by marrying the meek, effete French prince, Louis XVI.

Played brilliantly by Coppola’s cousin, Jason Schwartzman, the young man seems utterly uninterested in his new bride– which understandably complicates her efforts to produce an heir. She ultimately prevails, becoming a beloved figure throughout France for her youthful rebelliousness (a trait that doesn’t quite go away even when she becomes Queen).

Unfortunately, the sun is not destined to shine on Louis and Marie Antoinette’s reign for long: the combination of her decadent spending and his unwavering insistence on helping the American Revolution along by sending funds overseas earns them nothing but violent contempt from the French working class.

The daily economic hardships suffered by their subjects seem a world away from the gilded halls of Versailles– that is, until the rabble show up on their doorstep to demand not only the end of the French monarchy, but Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette’s own heads.

The tragic story of France’s last King and Queen is told with the assistance of an inspired supporting cast, each portraying an actual historical figure with a similar postmodern flair. Rip Torn plays King Louis XV as a well-respected (if a little pervy) ruler, while Asia Argento slithers around the palace as his slinky mistress, Contesse du Barry.

SNL alum Molly Shannon is well-suited to her character, gossipy noblewoman Aunt Victoire, as is Steve Coogan in his role as Marie-Antoinette’s lifelong counselor, Ambassador Mercy. Jamie Dornan’s performance as the smoldering Count Axel Fersen– with whom Marie-Antoinette initiates a secret love affair– foreshadows his breakout in a similar role in 2015’s FIFTY SHADES OF GREY.

A few other familiar faces stand out, like Danny Huston as Marie-Antoinette’s reassuring older brother, Emperor Joseph II, and a baby-faced Tom Hardy as a stoic soldier named Raumont. And last but not least, no conversation of MARIE ANTOINETTE would be complete without mention of my personal favorite cast member: Mops the pug, whose masterful turn earned him the Palm Dog award for Best Canine Performance at the Cannes Film Festival.

MARIE ANTOINETTE owes a clear debt to the visual style of Terrence Malick, Milos Forman, and Stanley Kubrick, who’s 1975 masterpiece BARRY LYNDON haunts nearly every frame. LOST IN TRANSLATION’s cinematographer Lance Acord returns, shooting once again in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio on 35mm film.

As evidenced by his work in LOST IN TRANSLATION, Acord is quite adept at working with soft, natural light– a strength that pays dividends in MARIE ANTOINETTE by faithfully rendering a pre-industrial society. The use of lens flares, especially in the sequences where Marie-Antoinette retreats to her small villa in the country, infuses Coppola’s story with a modern, casual edge that helps bring out her heroine’s interior state.

The film’s camerawork leans into the regal flavor of their setting, highlighting Marie-Antoinette’s increasing alienation from the royal court with formal locked-off compositions, steady dolly shots, and slow zooms. Acord’s work is harmoniously complemented by Coppola’s own brother, Roman, who serves as the second unit director in charge of capturing select shots.

Coppola even manages to find an opportunity to incorporate her signature shot– mounted on the side of a car, looking in on a character sitting in the backseat. Since there were no cars in 18th century Versailles, Coppola simply swaps in a carriage. It’s a small substitute, but it nonetheless reinforces her attempts to humanize the figure of Marie-Antoinette in the cultural parlance of today.

The use of the real halls and ballrooms of Versailles injects every frame with a palpable sense of history and grandeur, but returning Production Designer KK Barrett ably conveys a postmodern pop edge by providing fabulously ornate costumes, furnishing, and food in searing pastel colors like baby blue, hot pink, and seafoam green.

A sense of decadence and luxury pervades every lingering closeup of Marie-Antoinette’s material riches– Coppola even goes so far as to personally enlist legendary fashion designer Manolo Blahnik to provide the Queen’s endless supply of heels (2).

Little attention is paid to ensuring a temporal authenticity– in fact, Coppola and Barrett lean heavily into the film’s anachronistic elements, to the point that Marie-Antoinette is even seen wearing a pair of Converse sneakers. Indeed, it wouldn’t have been surprising to also see her donning a pair of Apple earbuds.

This, perhaps more than any other aspect of Coppola’s approach, is the most controversial and contested factor in the entire film. Critics fixated on the audacity of including the aforementioned pair of Chucks, or Coppola’s use of 80’s pop, shoegaze and punk tracks on a soundtrack that would traditionally be comprised of baroque classical compositions by Vivaldi (which, admittedly, Coppola does include to great effect).

Tracks from well-known New Wave bands like New Order, The Radio Department, and Gang of Four routinely pierce the stuffy bubble of regality that threatens to smother the film, creating a unique energy that many critics simply could not wrap their heads around.

In decrying Coppola’s vision by fixating on her decision to include anachronistic elements and music, they unwittingly prove that they miss the point entirely– and not just of the film, but art itself. At the risk of going off on a larger tangent, cinema is an art, and art is about expressing some kind of an emotional truth about the human experience.

The world of 18th-century Versailles might seem totally alien to someone living in the 21st, but Coppola’s use of modern touches allows her to transcend the time barrier and give us a direct line of emotional access to her characters’ fundamental humanity.

We can see ourselves in Marie-Antoinette’s youthful misadventures, and as such, the film is exceedingly more vibrant and relevant to our time than others of its ilk (even more so now, after Wall Street’s similar decadence led to the 2008 collapse and the rise of the Occupy movement, who resemble the angry French mob in wanting to string up the bankers responsible).

The life story of Marie-Antoinette provides ample opportunity for Coppola to further explore her key thematic fascinations. Like the ill-fated Lisbon sisters in THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, Marie-Antoinette has little agency of her own– she’s expected to adhere to a set of behavioral traits and customs that stifles her individuality.

She’s a kept woman, only coming into her own when she starts expresses herself and up-ending the court’s antiquated perception of how a Queen should act. The air of mystique that surrounds Coppola’s female protagonists reaches something of an apex in MARIE ANTOINETTE, finding a palpable charge in the eponymous Queen’s transgressive femininity.

She remains an elusive figure to those around her– even those as close as her own husband– and it’s precisely that unknowable quality that draws people to her like a magnet; they’re all trying to figure out the mystery of her inner life.

Dunst plays Marie-Antoinette with the same kind of emotional detachment that defines most of Coppola’s female protagonists. It’s a detachment rooted in loneliness– by virtue of her Austrian background, she is a stranger in a strange land. She’s eternally set apart from everyone else, exiled into her own interior state.

Roger Ebert perhaps said it best in his review: “This is Sofia Coppola’s third film centering on the loneliness of being female and surrounded by a world that knows how to use you, but now how to value and understand you”. (3)

Just as much as MARIE ANTOINETTE is an inward-looking film on a historical figure, so too is it an intensely personal film on Coppola’s part. The film’s extreme attention to detail in its costumes (and the narrative purpose thereof) echoes Coppola’s own association with the fashion world, but that’s merely the tip of the iceberg.

Her background as a child of privilege and status allows her to sympathize with her heroine’s plight. As such, MARIE ANTOINETTE marks something of a turning point in the artistic character of Coppola’s filmography. Beginning here, we see the director really begin to embrace her background as the daughter of a cinematic titan.

Growing up Coppola no doubt meant a childhood of frequent exposure to fine art (and fine wine), but it also meant being born with a pre-established air of pseudo-celebrity. Before she was a filmmaker, she was a globetrotting socialite– her peers were the offspring of other similarly influential and wealthy households.

She very easily could have become another Paris Hilton or a Kim Kardashian, but instead she exploits that familiarity with the world of empty celebrity (and our obsession thereof) to give her work an added layer of thoughtfulness and relevance– especially in the context of MARIE ANTOINETTE’s endless pageants of manners, customs, and decadence.

A vision as bold as Coppola’s is bound to beget equally bold reactions, and MARIE ANTOINETTE certainly received its fair share– on both sides of the aisle. Critics famously booed the film after its Cannes premiere, yet it also ran in contention for the festival’s highest honor: the Palm d’Or.

Domestic reviews were similarly mixed, with the audiences that made LOST IN TRANSLATION such a runaway success largely staying away; in the end, the film grossed only $60 million over its $40 million budget. $20 million is certainly nothing to sneeze at, but the bean counters at Columbia Pictures no doubt wrote it off as an underwhelming performance.

Still, MARIE ANTOINETTE’s inherent charms did not go unnoticed– many critics responded quite favorably to Coppola’s revisionist take on the French monarchy, placing lavish praise on its Oscar-winning costume designs in particular.

MARIE ANTOINETTE was released at the height of the aught’s prestige-picture bubble, shortly before it popped (along with the world economy) in 2008. In the years since, the film seems to have only grown in appreciation– time has made Coppola’s intentions more apparent, leading some critics to come around on their initial distaste for her usage of anachronistic elements and dub it one of the best American works of its decade.

To this author in particular, time has also made it apparent that MARIE ANTOINETTE marks Coppola’s emergence as a mature filmmaker (an ironic notion considering the story is about a youthfully immature heroine). Coppola’s pioneering vision remains as divisive as ever, but if you can manage to connect with MARIE ANTOINETTE on her own level, you just might find a beautiful and precious jewel of a film that’s as subversive as it is classic.

CHRISTIAN DIOR COMMERCIAL: MISS DIOR CHERIE (2008)

Of all the brands that director Sofia Coppola could have collaborated with on her first commercial, perhaps it’s appropriate that the honor went to the French fashion label Christian Dior. Coppola’s lifelong interest in haute-couture fundamentally informs her artistic aesthetic, to the point that any given frame from THE VIRGIN SUICIDES (1999), LOST IN TRANSLATION (2003) or MARIE ANTOINETTE (2006) could be mistaken for a fashion shoot by the casual observer.

As her artistic profile has risen, so has the balance of influence– many prominent fashion designers now reference Coppola’s work for their look books and photo shoots. It was only a matter of time until commerce sought to appropriate her cultural “cool factor”, which leads us to her 2008 spot for Christian Dior, titled “MISS DIOR CHERIE”.

The spot follows the format we’ve come to expect from a modern fashion commercial: a glamorous young woman frolicking about in urban vignettes– in this case, Paris. The piece plays evokes MARIE ANTOINETTE in its baroque, Old World setting while the handheld, naturally-lit cinematography and Brigitte Bardot’s midcentury pop song “Moi Je Joue” suggests a considerable debt to the traditions of the French New Wave (and a dash of Fellini for good measure).

The muted color scheme– comprised primarily of fashionable pastel pinks– echoes the female mystique that runs through Coppola’s filmography, employed here as a kind of carefree femininity; the kind that arises when a girl is comfortable and confident in her sartorial choices.

Coppola’s work here is evidence that her particular talents are naturally harnessed in service to the advertising industry. Despite serving the overlords of commerce instead of her own artistic self-fulfillment, her vision remains as distinctive and immediately identifiable as ever, and makes for memorable ad that walks the runway with its head held high.

SOMEWHERE (2010)

Growing up as a member of Hollywood royalty, director Sofia Coppola spent a large portion of her formative years in hotels, often accompanying her father, iconic 70’s auteur Francis Ford Coppola, on film shoots in various locations both near and far.

The lack of attachment to a singular house or place during her childhood appears to have a direct correlation with the dreamlike emotional detachment of her own film work as an adult– her protagonists are almost always adrift in a sea of malaise, simply occupying a space rather than living in it.

Watching her fourth feature effort, 2010’s SOMEWHERE, it becomes readily apparent that Coppola regards Los Angeles’ historic Chateau Marmont hotel as her own kind of home; a place in which she spent a great deal of her youth because of her father’s work.

Within these hallowed halls, Coppola feels a special kinship with the actors, rock stars, and fashionistas that have lived, laughed, and loved there. Over the years, Coppola has forged her own personal relationship with the hotel and its staff, to the extent that they would host one of her birthday parties and, like her all-access pass to Versailles Palace during 2006’s MARIE ANTOINETTE, allow her carte blanche use of the site for the shooting of SOMEWHERE.

After the extravagant period production of MARIE ANTOINETTE, Coppola was compelled to return to a simpler form of storytelling– a form that resembled her 2003 feature LOST IN TRANSLATION in that it served as more of a mood piece than a conventional narrative.

Indeed, SOMEWHERE plays like a close companion piece to her earlier film, dealing in the same feelings of alienation and uncertainty while effectively sealing off her protagonists from the outside world within the walls of a visually-distinctive hotel.

Coppola’s script drew inspiration from various aspects of her personal life (her own history with the Chateau Marmont and the birth of her second child) as well as a variety of other sources, from Bruce Weber’s Hollywood portraits, to Helmut Newton’s photos of models taken at the Chateau, and even Chantal Akerman’s 1975 film JEANNE DIELMAN, 23 QUAI DU COMMERCE, 1080 BRUXELLES (2).

SOMEWHERE— financed by Focus Features and produced by Coppola, her brother Roman, G. Mac Brown, and her father’s American Zoetrope studios– is especially unique within her filmography in that it is the first that follows a male protagonist: a burned-out film actor named Johnny Marco.

Played with effortless shabby-chic nuance by underrated character actor Stephen Dorff in a role written specifically for him, Marco is an artist who has lost sight of his art (1). He’s marooned within the Chateau, bogged down in the boring, everyday business of acting: being shuttled around to promo shoots and press conferences, attending vapid awards shows in glamorous locales like Italy and Las Vegas, and navigating the endless, snaking boulevards of Beverly Hills in his exotic (yet unreliable) sports car.

The only thing that seems to bring a sense of life into his eyes is the sight of his daughter Cleo, played by Elle Fanning as an ephemeral and precocious little sprite who flits in and out of his life with little warning. SOMEWHERE’s key narrative turns hinge on this delicate relationship between a father and his daughter, observing how their limited time together helps the other mature into a more self-realized person.

This being a portrait of Hollywood, Coppola also peppers the film with several winking cameos by other famous faces, like THE OFFICE’s Ellie Kemper as Johnny’s eager publicist, Michelle Monaghan as his acid-tongued co-star, JACKASS crew-member Chris Pontius as his one-man entourage, and Benicio Del Toro as an incognito version of himself.

SOMEWHERE’s cinematography befits its simple narrative approach, adopting an observational, rough-edged aesthetic that makes inspired use of old lenses from Francis Ford Coppola’s RUMBLE FISH (1983) shoot to imbue the 1.85:1 35mm film frame with a timeless, vintage aura (1).

One of the last films lensed by the late cinematographer Harris Savides, SOMEWHERE revels in the long take, mixing and matching between the formalism of locked-off slow zooms and the immediacy of handheld shots. Savides was a master of harnessing soft and natural light, and SOMEWHERE stands as a testament to his abilities in that regard while reinforcing Coppola’s own established aesthetic.

SOMEWHERE contrasts MARIE ANTOINETTE’s vibrant palette of candy-coated hues with a muted color scheme that deals in creamy neutrals and rosy highlights. The film’s opening shot– a long static composition of Marco’s sports car speeding around a closed loop– establishes the elliptical nature of Coppola’s storyline, reinforced by returning editor Sarah Flack’s patient pacing and oblique assembly of key dramatic moments.

As in her previous films, Coppola uses music to striking effect, creating a soundscape where well-worn Top 40 hits are primarily heard as a diegetic element that reflects the cultural idea of what constitutes a “Hollywood Lifestyle”.

Coppola deviates from this approach only once, laying Julian Casablancas’ mellow track “I’ll Try Anything Once” over a sequence of Marco and his daughter enjoying a fleeting moment of happiness and connection in the hotel pool. The effect is a subtle, yet transcendent moment for the audience as well as the characters.

Coppola unifies her disparate musical elements with an ethereal electronic score by French pop band Phoenix (of which her husband, Thomas Mars, is the frontman; continuing the long Coppola family tradition of artistic collaboration with other members).

SOMEWHERE contains many of the surface elements of Coppola’s established thematic signatures– autobiography, the fashion world, celebrity lifestyles, and the feminine mystique– but it also expands on them in interesting and insightful ways that show Coppola’s growth as a mature artist.

Her decision to make her protagonist a man throws her longtime examination of womanhood into sharp relief, casting each female character on either side of the male gaze, assigned a corresponding value between sexual appeal and innocence.

SOMEWHERE predicates its main narrative thrust on the paper-thin conflict between Marco and his self-doubt, or the tension between himself and the expectations of others from both his professional and personal life. However, where Coppola’s film really resonates is in the dichotomy of the roles that women play in his life.

As a rich and successful movie star living in a glamorous Hollywood hotel, Marco is surrounded by beautiful women that serve as all-too-willing sexual playthings. The women of the Chateau are so sexually adventurous that he merely needs to flash a smile for them to jump into bed with him.

As a father to a young girl, however, he has to reconcile the carnal aspects of himself with the responsibilities of raising someone who will one day be a woman too, complete with a self-realized sexuality of her own. Marco’s interactions with his daughter are geared towards preserving the innocence of childhood amidst the wanton hedonism of his lifestyle, but in trying to protect her purity he also denies her a fundamental aspect of her emerging humanity.

The major breakthrough in their relationship comes when he directly acknowledges the complicated nature of adult life (signified by the failed relationship between him and her mother)– an act that requires him to view Cleo as not just his young daughter, but as an intellectual equal and a mini-adult in her own right.

SOMEWHERE’s secondary thematic exploration concerns the lifestyles of the rich and famous, a constant presence throughout Coppola’s work. Like LOST IN TRANSLATION, SOMEWHERE follows a once-successful actor on the downslope of his career, but whereas the former’s exotic Tokyo setting hinted at a vibrant, sprawling world just waiting to be discovered, the latter’s depiction of sunny LA feels confining– twisted into a kind of limbo that only resembles paradise; purgatory with a pool.

As suggested in the aforementioned opening shot, Marco’s life is something of a closed loop: he wakes up every morning late for some photo shoot or promo event he forgot about, spends the afternoon driving around aimlessly, and then drinks himself stupid to the lullaby of two blondes’ pole-dancing his hotel room… all so he can wake up the next day and do it all over again.

Even when he’s high up in the air, surveying the city below in one of Coppola’s signature backseat reverie shots, he’s still confined within a cramped helicopter cabin. Over the course of its running time, SOMEWHERE slowly shows how Marco’s connection to his daughter allows him to break out of his personal purgatory, evidenced via the closing shot that shows Marco abandoning his sports car (and thus the closed loop) altogether– setting out on foot towards an uncertain, but invigorating future.

After the gilded extravagance of MARIE ANTOINETTE, SOMEWHERE marks a return to the minimalistic form that defined LOST IN TRANSLATION. However, the film didn’t experience the same warm reception enjoyed by its predecessor.

Critics mostly responded to the film with a tempered positivity, but those with a negative reaction felt very strongly about its perceived failings. Those already predisposed to blast Coppola for her artistic indulgences were given even more fuel for the fire, citing SOMEWHERE as her most irrelevant and empty exercise to date.

Even its biggest critical win– the prestigious Golden Lion award for Best Picture at the Venice Film Festival– came under heavy criticism due to the fact that Quentin Tarantino, who once was romantically linked to Coppola, had championed the film in his capacity as the jury chairman.

This episode is a particularly unfortunate one in the annals of film criticism, in that it reinforces the deeply-entrenched marginalization of female directors by suggesting that her win only happened because of her relationship to a man, and not because of her own artistic abilities.

That being said, SOMEWHERE isn’t a particularly easy film to love; it refuses to traffick in digestible conflict or play into audience expectations. Scant as its story may be, the film is nonetheless a sublime love letter to a unique refuge within LA’s sprawling megalopolis, crafted with sensitivity and subtlety by a confident artistic voice without compromise.

Of all the films in Coppola’s career, SOMEWHERE provides the most profound and intimate insights into her unique character, allowing us to look past the glitz and glamor to find the complicated, brooding soul deep inside.

COMMERCIALS AND MUSIC VIDEOS (2010-2013)

Between the release of her 2010 feature SOMEWHERE and 2013’s THE BLING RING, director Sofia Coppola would keep her skills sharp by taking commission work that further established her influence in the commercial, music video, and fashion film realm.

Her previous advertising work hinted at the harmonious synergy that her aesthetic could bring to fashion and luxury brands in particular, but her output during this three period would cement her inherent appeal in that arena.

CHRISTIAN DIOR: CITY OF LIGHT (2010)

Thanks to her reputation as a filmmaker who can coax career-best work from her cast members, Coppola can command some serious star power whenever she steps behind the camera– even when said production is for the latest Christian Dior perfume.

Titled “CITY OF LIGHT”, her 2010 spot features established actress Natalie Portman and the up-and-coming Alden Ehrenreich slinking around the streets of Paris in elegant black-tie formalwear to the seductive strains of Serge Gainsbourg’s “Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus”.

Coppola’s distinct aesthetic is immediately identifiable– soft light, lens flares, and ephemeral handheld camerawork rendered in feminine hues like blush and cream. The piece makes significant use of the idea of “the little black dress”, a hallmark of cosmopolitan female sexuality and mystique, while shots of Portman donning oversized sunglasses in the bath echo Coppola’s career-long exploration of celebrity and glamor.

H&M MARNI (2012)

To promote their 2012 collaboration with Italian fashion brand Marni, H&M commissioned Coppola to shoot a distinctive spot featuring young actress Imogen Poots on a moody summer night at a desert retreat amongst other beautiful people.

Coppola recruits her SOMEWHERE cinematographer Harris Savides to lens the spot, once again incorporating lens flares, soft natural light and a lingering pace to imprint her distinct stamp. Several of her recurring thematic fascinations make an appearance here, wrapped up in the unmistakable iconography of California-cana: Palm trees, pools, and the back seats of cars.

“MARNI” had a high-profile rollout for a commercial, earning prominent placement and critical coverage that would position the spot as one of Coppola’s most iconic.

MARC JACOBS: “DAISY PERFUME” (2013)

In 2013, Marc Jacobs enlisted Coppola to direct a spot titled “DAISY PERFUME”, featuring a group of young blondes frolicking barefoot in a sun-kissed field. The idea isn’t exactly novel, but Coppola nevertheless manages to make it distinctive by harnessing the feminine mystique of Peter Weir’s 1975 classic PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK (as well as her own 1999 debut, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES) via the dressing of the girls in long white dresses that stand out against the pastoral scenery.

The bright cinematography flares with natural light and an airy looseness while electronic music courses underneath on the soundtrack. “DAISY PERFUME” isn’t the most memorable spot Coppola has made, but it still bears the undeniable mark of her hand.

CHRISTIAN DIOR: LA VIE EN ROSE PERFUME (2013)

Coppola delivered her third spot for Christian Dior in 2013, working once again with Natalie Portman to promote the brand’s La Vie En Rose line of perfume. Set to a new rendition of the eponymous track made famous by Edith Piaf, the style of “LA VIE EN ROSE PERFUME” recalls the pastel color palette of blues, pinks, and creams that Coppola applied to MARIE ANTOINETTE.

The natural sunlight flares into the frame, reflecting a casual and carefree approach to the camerawork, while a gauzy soft focus is employed to round off harsh edges. A fleeting reference to Federico Fellini’s LA DOLCE VITA (1960), wherein Portman happily splashes around inside a fountain, is a particularly nice touch.

The feminine mystique that enshrouds Coppola’s aesthetic is embodied in the glamorous allure of Portman as well as the unattainable air of her celebrity. However, the effect isn’t as potent as it tends to be in her feature work– the mystique tends to diminish when it can be commodified as a tangible quality inherent in an item of clothing.

With its seductive glimpses of the LA celebrity lifestyle– swimming pools, sunglasses, and classic cars– “LA VIE EN ROSE PERFUME” slides quite easily into place as yet another succinct example of her unique artistic signature.

PHOENIX: “CHLOROFORM” MUSIC VIDEO (2013)

For her first music video in nearly a decade, Coppola teamed up with her husband Thomas Mars to promote his band Phoenix’s new single “CHLOROFORM”. Like her video for The White Stripes’ “I JUST DON’T KNOW WHAT TO DO WITH MYSELF”, “CHLOROFORM” is built around a very simple concept stretched out along the track’s length.

Shooting in black and white with a slight rose tint, Coppola first shows the band performing in silhouette, the definition of their forms almost lost to the moody wells of shadow surrounding the edge of the frame. The bulk of the piece dedicates itself to a slow-motion dolly shot featuring young women watching from the audience.

Their faces– juxtaposed in shallow focus against the bokeh of fuzzy light orbs– are twisted into varying expressions of rapture, heartbreak and awe, projecting a nuanced and dignified beauty that could only be realized by someone as well versed in the inner life of femininity as Coppola is.

That being said, there’s something slightly odd (and maybe even amusing) about a director placing her husband on a pedestal for the worship and adoration of other young girls; a kind of winking in-joke to the nature of intimacy in the context of celebrity that could only come from the mind that devised SOMEWHERE.

Being the independently-minded auteur she is, Coppola isn’t necessarily the kind of filmmaker who can (or even should) stake her legacy on the box office performance of her feature work; her thematic interests and those of the megaplex crowd don’t exactly intersect.

Besides providing her with a steady stream of income, the advertising arena proves crucial to her development as an artist because it gives her an opportunity to experiment while maintaining her influence within pop culture.

Just as David Fincher helped to shape the distinct characteristics and conventions of the music video genre, so has Coppola’s unique style informed the legions of up-and-comers in the fashion film and branded content realm.

Having worked at a production company that produced a substantial amount of fashion films in particular, I can tell you from personal experience just how much Coppola’s style has influenced the next generation of directors– no matter the content, each piece bore some kind of creative debt to her aesthetic.

Her string of commercials and content during this three year period solidified her palpable influence, enabling her to weather the still-unfolding economic storm that would see the drastic drawdown of the mid-budget prestige pictures that enabled her rise.

THE BLING RING (2013)

The inherent superficiality of Hollywood, Los Angeles, and the greater cultural landscape that constitutes “SoCal” has been well-established over the past several decades. The Golden State’s wealth and fascination with celebrity has created a value system based on material goods and the pursuit of fame and leisure in all its forms.

Those who move here in their adult years tend to keep a sense of perspective, embracing SoCal’s myriad pleasures at arm’s length. But for those who are born and raised here, these material values can become their entire world– not having the latest BMW coupe or Chanel handbag is, quite literally, a matter of life and death for those more concerned with image over identity (or, more aptly, those who think the two are one in the same).

Frankly, I’m deeply anxious at the prospect of bringing up children of my own in this climate, where the biggest barometer of a person’s worth is how many Instagram followers one can accumulate. In this light, a film like director Sofia Coppola’s fifth feature, THE BLING RING (2013)– wherein a group of overprivileged LA teenagers steal from the homes of celebrities and socialites in an attempt to live like them– is my greatest nightmare writ large.

Based on Nancy Jo Sales’ 2011 Vanity Fair article, “The Suspect Wore Louboutins”, Coppola’s script slightly fictionalizes the real-life exploits of the titular Bling Ring during their short-lived reign of terror– or, considering the staggering wealth of their targets, reign of inconvenience.

The story takes place in the wealthy suburban enclave of Calabasas, which has gained a reputation for surface glamor and trashy materialism thanks to the small population of reality stars, pop divas, fame chasers, and any number of Kardashians that call its endless rows of gaudy McMansions home.

It’s an honest mistake for non-Angelenos to make, but it bears repeated mentioning that Calabasas is not LA– a fact that THE BLING RING’s fresh-faced kleptos are all-too-painfully aware of as they gaze out at LA’s twinkling lights from a distance.

With the exception of Emma Watson and Leslie Mann, Coppola’s cast is composed primarily of unknowns– anchored by newcomers Katie Chang and Israel Broussard. Chang, who had never been in a film before and only scored the role off the strength of her self-tape, plays the crew’s ringleader, Rebecca.

Rebecca’s love for fashion combines with a reckless amorality to create a sociopathically nonchalant teenager that effortlessly convinces the introverted new kid, Mark– played with a nuanced sexual ambiguity by Broussard– to rob nearby homes with her.

What begins as a way to combat their everyday suburban boredom soon grows into an all-consuming compulsion that ropes in their friends: aloof bad girl Chloe (Claire Julien), playful Sam (Taissa Farmiga) and the frighteningly vapid Nicki, played by Watson in a scene-stealing performance that she watched a disturbing amount of reality television to prepare for.

Adults hold little influence over the Bling Ring’s self-contained world of shiny baubles and expensive trinkets, which is not to say that their guidance would even be particularly helpful in the first place. Mann’s Laurie, the only prominent adult in the film, is the kind of parent that would let kids get drunk at her house after prom; a self-styled “Cool Mom” whose utter ineffectiveness as an authority figure is rooted in her devotion to “The Secret” and its snake-oil “religious” message just as much as her obliviousness to what’s going on around her.

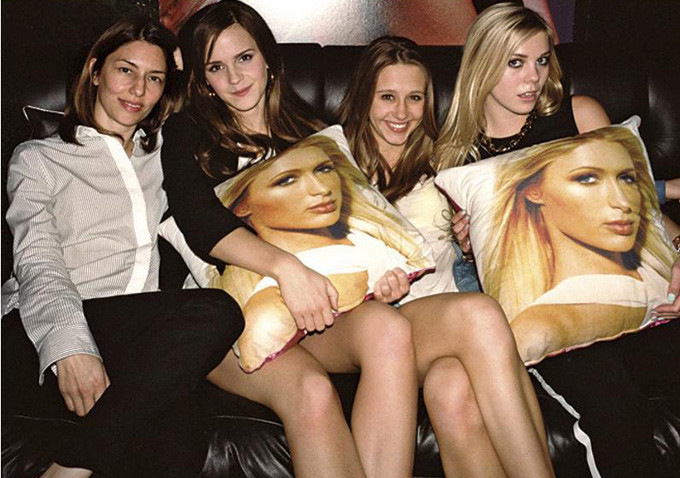

As the young criminals grow increasingly bolder in their exploits, they are seduced by the glitzy Hollywood lifestyle they think they’ve become a part of. They may be partying in the same clubs as Paris Hilton and Coppola-regular Kirsten Dunst (each making brief cameos as themselves), but they’ll never truly be in those social circles– no matter how many of Hilton’s shoes they have in their possession.

They believe they’ll never have to answer for their crimes, despite conducting their raids on fleeting whims and making no effort to disguise their identity from security cameras. Their perceived invincibility proves the Bling Ring’s ultimate downfall, and it’s only a matter of time until the authorities bust down their doors.