In the larger film community, director Paul Thomas Anderson is widely considered to be one of the greatest living directors in America. While his output is relatively small compared to his peers, each of his films is of such an impeccably high caliber that his impact on the medium is undeniable. Affectionately called PTA by his fans, Anderson is held up by his contemporaries as a shining example of a true artist creating truly important work—high praise for a man who has yet to even win an Oscar for himself.

Filmmakers of my generation look to Anderson like the Film Brat generation looked to Stanley Kubrick—a god walking among us, an elder young enough to accessible, an ideal to which we aspire. It should come as a surprise to no one that Anderson is a profound influence on my own work. I had first heard rumblings of his greatness towards the end of high school, when all the artsy drama kids could talk about was 1999’s MAGNOLIA during its cult resurgence on DVD a few years after its release.

When I entered Emerson College as a second-semester freshman, my roommates sat me down to watch 1998’s BOOGIE NIGHTS, his second feature and his mainstream breakout. I was instantly hooked. Anderson was the first filmmaker where I could actually see how his work was constructed and subsequently desired to emulate it. He was a role model and a guiding light in the crucial moment of my life when my paradigm of what film could be was radically blown open.

To later find out that Anderson too attended Emerson (albeit only for a year) was a moment of untold delight for me—validation that I was on the right path towards a rewarding, fulfilling career in filmmaking.

Born in 1970 in Studio City, California, Anderson is firmly a member of Generation X, whose filmmakers were raised on an endless diet of movies on videocassette. The first to cut their teeth using cheap video and not expensive film, they could afford to make mistakes– and they made plenty of them.

Like his peers Steven Soderbergh and Quentin Tarantino, he broke out as a professional director in the heady days of 90’s independent film, catapulted into the limelight by a formidable debut at the Sundance Film Festival. But unlike Tarantino and Soderbergh, Anderson came from a family already well-steeped in the entertainment industry.

His father, Ernie Anderson, had been a late night horror TV show host under the name of Ghoulardi—a name that Anderson would later appropriate for his own production company.

At the age of eight, Anderson made his first home movie, and at twelve he began regularly making them with his father’s Betamax video camera. His father encouraged his pursuits, unconsciously enabling them by providing the junior Anderson with a never-ending source of creative character fodder- Ernie’s own eccentric showbiz friends. From this ragtag collection of aging hooligans, PTA drew inspiration and began to forge a distinctive voice for himself.

By age seventeen, Anderson felt ready to tackle his first “serious” project. He recruited the talents of his father and his friends, and raised the money he needed to shoot by taking on a job as a birdcage cleaner. He wanted to make a film about John Holmes, the legendary pornographer with a legendarily large package. He was fascinated by the subculture of pornography, at least as it existed in the late 70’s when it was still relatively underground and unregulated.

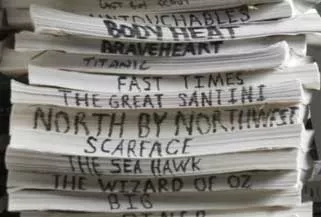

Stylistically, he was influenced by Rob Reiner’s THIS IS SPINAL TAP (1984) and its comedic documentary conceit. All of these elements converged to form THE DIRK DIGGLER STORY (1988), a mockumentary about the eponymous, John Holmes-inspired porn star with a large endowment rivaled only by an even larger ego. Clocking in at 30 minutes (noticeably long for a first work), the short plays like an early blueprint for his breakout feature BOOGIE NIGHTS by featuring prototypes of characters and the same basic plot progression found in the full feature.

Anderson’s friend Michael Stein plays the role of Dirk Diggler, establishing the character as a combative, egotistical force of nature long before Mark Wahlberg got his hands on the part. Bob Ridgely, a friend of Ernie Anderson’s, plays the role of director Jack Horner (later inimitably played by Burt Reynolds in his career comeback).

Ridgley wrings a lot of emotion out of his role, despite hiding his eyes behind giant black sunshades. Other core characters from BOOGIE NIGHTS make their prototypical appearance here, like John C. Reilly’s Reed Rothchild in the form of an impossibly buff Eddie Delcore and Rusty Schwimmer’s Candy Kane, an early version of Julianne Moore’s Amber Waves.

HARD EIGHT (1996)

Screening his short film CIGARETTES & COFFEE at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival was a transformative event in director Paul Thomas Anderson’s career. Not only was he invited to workshop his film in the Sundance Institute’s prestigious Directors Lab, but he was also approached by producer Robert Jones, who offered his assistance in expanding the film into a feature.

Naturally, Anderson went to work, developing his short into a larger story that concerned itself with an aging gambler who will do anything to hide his dark past from a pair of close friends he’s come to love as if they were his children. Anderson lovingly gave his story the name SYDNEY, like he was naming a child. His experience in making the film, however, was anything but blissful.

He was hamstrung by Jones’ constant meddling and sizable ego, and further compromised by an inept distributor (Rysher Entertainment) that strong-armed his film away from him only to dump it into theaters with little fanfare. That film exists now as HARD EIGHT (1996)—beloved with immense fervor by Anderson’ cult of followers but completely overlooked by the mainstream film community. Last released as a bare-bones DVD in the early 2000’s, HARD EIGHT is in desperate need of a latent rediscovery and a restoration of Anderson’s original vision.

In a diner in the middle of the Nevada desert, an old man named Sydney (Philip Baker Hall) offers a forlorn-looking young man named John (John C. Reilly) a cigarette and a cup of coffee. They get to talking, and John reveals that he’s just lost all his money in Vegas after going there in hopes of winning enough money to pay for his mother’s funeral. Sydney takes pity on this poor soul, offering to take him to Reno and teach him a little trick that will net him some money at the casinos.

Two years later, John and Sydney are nearly inseparable—that is, until a streetwise cocktail waitress and sometimes-hooker named Clementine (Gwyneth Paltrow) enters their life. Initially, the three form something of a family unit, with Sydney acting as the father figure. However, Clementine risks everything when she makes a bloodied hostage out of a cheap john who won’t pay up. Fearing the legal repercussions of Clementine’s actions, Sydney urges her and John to flee the city and lay low for a while.

At the same time, he’s approached by John’s friend Jimmy (Samuel L. Jackson), a smooth operator who knows a secret about Sydney’s dark past– a secret that would destroy Sydney’s little family unit forever.

Veteran character actor Philip Baker Hall finally steps into the limelight as Sydney, a paternal and patient soul. He’s a helper of people, seemingly trying to atone for some great wrong he’s done in his life. Hall brings a great deal of class and respectability to the film, expanding upon his role in CIGARETTES & COFFEE with an involved performance that might just be his best. Known primarily for his Judd Apatow comedy gigs, John C. Reilly turns in a rare dramatic performance as the anxious, yet loyal John.

Reilly plays the character like a dog who doesn’t know any better, constantly screwing up and depending on Sydney to bail him out. John is a lost young man, deeply in tune with his emotions but unable to properly express them.

Gwyneth Paltrow is convincing as the cynical, disillusioned cocktail waitress/hooker Clementine. Considering her real-life personality, the role of Clementine is an extremely edgy one for her. She courageously lets her makeup smear and doesn’t shy away from the inherent ugliness of the character’s personality. As Jimmy, Samuel L. Jackson is dangerously slick and unpredictable.

The 90’s were Jackson’s heyday, seeing him turn in unforgettable performances for directors like Quentin Tarantino and Steven Spielberg. His trademark pitch-black charm is present all through HARD EIGHT, providing yet another variation on that Jackson persona we all know and love.

Over the years, actors like Hall and Reilly have become a core part of Anderson’s repertory of performers. A few cameos contained in HARD EIGHT illustrates the foundations of this repertory, like the appearance of Oscar-winning actor and regular Anderson collaborator Phillip Seymour Hoffman as a cocky craps player, and THE DIRK DIGGLER STORY’s Robert Ridgley turning up briefly as a schmoozing keno manager.

Anderson’s repertory isn’t just limited to the talent, it extends to the skilled craftsmen he employs to help bring his stories to life. As his first feature, HARD EIGHT naturally sees the first instance of collaboration with several of them. Robert Elswit serves as the cinematographer, shooting on Super 35mm film and helping to establish Anderson’s formalistic aesthetic.

The film is presented in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, but it wasn’t shot in anamorphic, despite Anderson’s desire to do so (budget constraints). The visual presentation applies the same approach used in CIGARETTES & COFFEE—a classical, economical style of photography that’s short on fuss and long on power.

The gaudy Reno setting and a low-key lighting scheme lends HARD EIGHT a loungy, neo-noir vibe. This is also reflected in Anderson’s constantly moving camera, which is always precise and never frenetic. He utilizes graceful dolly moves, using handheld cameras only sparingly to convey immediacy. More notably, Anderson incorporates several Steadicam tracking shots that create a slick energy and sense of space.

While he would later use the Steadicam to more striking effect in his later films, Anderson keeps its usage in HARD EIGHT relatively simple, following Sydney as he walks through the casino floor, or as he approaches the fateful motel room that will shake up his adopted family unit forever. Overall, Anderson chooses to cover a lot of his close-ups in profile, which subtly conveys a feeling of precision and thoroughness in his compositions.

HARD EIGHT also marks the first time that Anderson works with the musician Jon Brion in a score capacity. Brion collaborates with Michael Penn to create a jazzy, cool-cat sound that accurately reflects both Reno and Sydney’s aged sophistication. The film also contains the first instance of a particular tonal bell cue—dark and relentlessly foreboding.

It works so well that Anderson opts to use it again in his later works, unconsciously creating a musical bridge between his first few films. A couple Christmas songs litter the soundtrack in order to give us a sense of the film’s wintery setting (because we’re in the desert, we wouldn’t know it’s December otherwise). Furthermore, an Aimee Mann song shows up in the end titles, which is notable because Mann would later become a very important collaborator for Anderson in his 1999 feature MAGNOLIA.

Of all the themes that Anderson continually explores throughout his career, the theme of the family unit is the most apparent in HARD EIGHT. The characters have all adopted each other in some fashion, as they all seek the comfort of companionship in a cold world. Sydney and John share a father/son relationship, while John takes the very literal step of inducting Clementine into his family by marrying her.

Sydney’s unconditional love and uncompromising generosity towards his young charges is revealed to come from a terrible secret that threatens to undo their union, thus the theme gives the film its stakes and driving force. The tone is very similar to CIGARETTES & COFFEE, with the first scene of HARD EIGHT lifted nearly directly from the short. Nonetheless, Anderson does a fantastic job expanding the scope and changing the focus of his story while creating a consistent tone.

While the process of production was relatively painless, Anderson’s experience in post-production was a hard lesson in the corporate obstinance of the studio system. He was faced with a difficult distributor in Rysher Entertainment, who wanted him to change the film’s name from SYDNEY to HARD EIGHT out of a fear that people would mistake the film for being about the city in Australia.

Anderson begrudgingly acquiesced to their demands, but they weren’t about to stop there. Producer Robert Jones became a constant source of headache, refusing to give his consent for Anderson’s request to place the credits at the end of the film instead of the beginning (despite the rest of the cast and crew being fine with it). When Jones and the studio balked at Anderson’s 150-minute director’s cut, the young auteur refused to make any cuts and was subsequently fired. Rysher took the film away and re-cut it.

Anderson’s original vision was validated when HARD EIGHT was accepted into Cannes’ Un Certain Regard program—on the condition that his director’s cut was the version to be screened. After the festival, Anderson’s cut was never seen again, and the finished film languished on the shelf for two years after Rysher suddenly (and unsurprisingly) went belly-up. Given how much of a mess Anderson’s experience in post-production on HARD EIGHT was, it’s something of a miracle that his debut turned out as assured and confident as it did.

A dismissive attitude towards the film hasn’t stopped the home video market from reclaiming HARD EIGHT as a lost treasure. Most cinephiles agree that it’s an underrated gem of a film, a work on par with any of Anderson’s best. While it exists today as an outdated transfer on a bargain bin DVD, HARD EIGHT marks the humble starting point of one of our greatest contemporary auteurs.

Until somebody (come on, Criterion) comes along and releases the director’s cut, we’ll just have to content ourselves with a watered-down, abridged version that provides fleeting glimpses into a brilliant young filmmaker finding his footing.

BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997)

For most filmmakers, every one has that singular film that serves as a flashpoint in their own individual development; a film that lets them see the whole medium of cinema through new eyes, informing and shaping everything that comes after it. My flashpoint arrived in the winter of 2005—I had just moved to Boston to attend Emerson College, and my film watching experience was limited to whatever was new in theatres or at Blockbuster.

One night, my new roommates sat me down to watch a film by a director I had never of heard of before—Paul Thomas Anderson. The film? Anderson’s second feature:BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997). I was transfixed; riveted by the subtle layers and subtext unfolding before me in such rich, dynamic and new ways. BOOGIE NIGHTS is one of my favorite films of all time—a film that I return to time after time for inspiration and guidance.

Despite having previously made the well-received HARD EIGHT in 1996, BOOGIE NIGHTS became Anderson’s breakout force and announced him to the film community as a bold, new force to be reckoned with. The success of HARD EIGHT had enabled access to the executives at New Line Cinema, who wanted to help him make his follow-up.

With these powerful forces at his side, Anderson turned to his 1988 short, THE DIRK DIGGLER STORY, for inspiration in creating the backbone of a new story. He fleshed this little nugget out into a sprawling meditation on the San Fernando Valley’s pornography industry over two decades of success and upheaval.

BOOGIE NIGHTS begins amidst the glittering disco lights of 1977, before the specter of AIDS took away the notion of free love without consequences and spurred heavy government regulation on the porn industry. Eddie Adams (Mark Wahlberg) is a young high school dropout from Torrance who buses into his nightly job as a bar-back for a disco club out in Reseda.

Eddie is a quiet, unassuming boy, save for his hidden talent: an abnormally large penis, which he uses to generate extra income by masturbating in front of strangers for money. One night, he meets Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds), a director of exotic adult films who invites Eddie into his world with a friendly smile and a firm handshake. Eddie eagerly takes Horner up on his offer, quickly ingratiating himself into the larger-than-life world of pornography and finding a close-knit family in the group of collaborators that Horner has assembled around himself.

Eddie takes the stage name Dirk Diggler, and with his inherent natural talent and sexual prowess, soon takes the entire operation into the stratosphere. Diggler and company ride high through the remainder of the 70’s, but a murder/suicide committed in Jack’s house on New Year’s Eve 1979 welcomes the 80’s with a foreboding, bloody omen.

The dawn of a new decade also heralds the arrival of a new technology that promises to upend the industry as they know it: videotape. As video becomes more commonplace, Jack Horner and company find their artistic integrity compromised, and their personal lives significantly altered for the worse. As Dirk strays increasingly further from Jack’s clan, he risks destroying himself upon the very altar of his own success.

Despite dealing with such lurid subject matter, Anderson finds a peculiar kind of dignity and grace within his characters. He shows us that pornographers are people too—just as capable of real love as we are. Before BOOGIE NIGHTS, Wahlberg was “Marky Mark”, a young rapper with a few unimpressive film credits to his name, but the role of Dirk Diggler established him as a genuine acting force that persists to this day.

Reynolds is inspired casting as the patriarch of his little porno family/empire. Like John Travolta in Quentin Tarantino’sPULP FICTION (1994), Reynolds’ against-type performance resulted in a newfound cultural relevancy after a long spell of waning popularity, eventually culminating in an Oscar nomination for his performance. Ironically, Reynolds hated the role and didn’t get along with Anderson during filming. He even went so far as to fire his agent for recommending the role to him.

Julianne Moore counters the two-fisted machismo of Wahlberg and Reynolds as Amber Waves, Horner’s wife and a mother figure to Dirk. She’s heartbroken over her real son being taken away from her by child services, so she turns to Dirk for a surrogate relationship—one that becomes incestuously sexual. Moore turns in one of her most beautiful performances here as a conflicted, inherently sad woman with deep reservoirs of unconditional love, walking away with an Oscar nomination for her efforts.

BOOGIE NIGHTS also serves as an establishment of Anderson’s close-knit repertory of performers—actors who have come to regularly appear in his films throughout his career. These include Luis Guzman (as a nightclub owner and pornstar-wannabe), John C Reilly (as Dirk’s doggishly loyal friend and co-performer), William H Macy (as the disgruntled, cuckolded assistant director), Ricky Jay (as the droll cinematographer), and Philip Baker Hall (as Floyd Gondolli, a smug rival of Jack Horner’s who personifies the encroaching malevolence of videotape).

Are you Tired of Paying Film Festival Entry fees?

Learn the techniques that worked in 600+ film festival entries. Download our six tips to help you get into film festivals for cheap or free.

On the female side, there’s Melora Walters as a sweet and naïve porn actress, and Heather Graham as the plucky, somewhat-ditzy Rollergirl. Further rounding out the cast is Don Cheadle as urban cowboy Buck Swope, Thomas Jane as cocky bad boy Todd Parker, and Bob Ridgley, who starred as Jack Horner in THE DIRK DIGGLER STORY and makes his last film appearance before his death here as The Colonel, an eccentric dandy who finances Jack’s films.

And last but not least, there’s Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Anderson’s closest acting collaborator who tragically passed away last week. He left behind an enduring legacy of masterful performances, one of which is found in BOOGIE NIGHTS’ Scotty J, a sexually confused and awkward boom operator who carries a one-sided torch for Dirk.

BOOGIE NIGHTS is the work of a young, ambitious filmmaker with bottomless reserves of zeal and talent. The tone is a distinctive blend of the multiple-perspective affectations of Robert Altman and the volatile, kinetic energy of Martin Scorsese. HARD EIGHT’s cinematographer, Robert Elswit, returns to shoot the film in the true anamorphic aspect ratio of 2.35:1 (achieved this time via actual anamorphic lenses and not a workaround like Anderson and Elswit had done previously).

Bob Ziembecki’s authentic period production design never reads as over-the-top and kitschy, instead popping from the frame in appropriate blasts of psychedelic color. The brilliant performances and Anderson’s bold narrative are aided by a constantly-moving camera that glides through the various scenes like an unstoppable rollercoaster. Even from an early age, Anderson has utilized the camera more confidently and audaciously than any of his peers, effortlessly mixing Steadicam, dolly, and handheld shots into a coherent whole.

Anderson’s use of the Steadicam in particular is worth noting, choosing to cover many of the scenes in long, traveling shots. The most notable of this is BOOGIE NIGHTS’ opening shot, which is, bar none, one of the best openings in recent film history. We start on a neon marquee flashing the film’s title, and then crane down to reveal a lively street scene that establishes both the setting and the time period.

Then, without skipping a beat, the camera operator steps off his platform on the crane and then enters Guzman’s nightclub as Anderson introduces us to all the major players of the story in one unbroken take, a la Altman’s iconic opening to THE PLAYER (1992). Of course, all this virtuoso camerawork wouldn’t be nearly as effective without editor Dylan Tichenor to stitch it all together. The film runs nearly three hours long, but if feels half that length thanks to Tichenor’s breathless pacing and exuberant sense of energy.

A major commercial selling point of BOOGIE NIGHTS was the music—specifically, the glut of 1970’s and 80’s pop hits that likely moved more copies of the soundtrack CD than the actual film itself. Anderson’s ear for music is spot-on, using several well-known cues in interesting ways that fill out the reality and authenticity of the period. The indulgence of the era is reflected in the glitzy needledrops, oftentimes creating an association between song and picture that becomes forever joined in the mind.

One instance of this is a scene where Alfred Molina’s drug dealer character sings along to Rick Springfield’s “Jessie’s Girl” during a particularly foreboding business exchange. It’s an unbearably tense sequence and a master-class in direction even without the music, but its inclusion transforms the scene into a truly transcendent moment.

For the score, Anderson recruits HARD EIGHT’s Michael Penn, who bases his musical palette around an inspired conceit—a carnival. The film opens against black with a somber dirge that sounds like a sad clown flailing around under the big top, a theme that reprises itself later on as a motif signifying Jack Horner’s little family unit.

The strange, carnivalesque nature of Penn’s score reflects Anderson’s bizarre, yet touching display of humanity while highlighting the hidden similarities between two decidedly different performance-based occupations.

Several of Anderson’s thematic preoccupations are present here, coalescing into an identifiable set of tropes. As a member of the first generation to come up under the rise of video, Anderson’s incorporation of the medium is more involved than any other filmmaker of his ilk.

In BOOGIE NIGHTS, the arrival of video is a major plot point, throwing the industry into a state of massive flux and becoming the fulcrum of conflict between Reynolds and Hall’s characters. Videotape highlights the characters as ideological opposites, fighting a war that pits economics vs. artistry—a conflict that can be argued to encapsulate the film industry as a whole.

To the characters of BOOGIE NIGHTS, video is a harbinger of doom and betrayal. Its arrival coincides with the fall of Dirk Diggler and Jack Horner, the fallout on their professional and personal lives being akin to a devastating meteor, or a nuclear bomb. BOOGIE NIGHTS shows remarkable prescience in its insights into video’s role in the video arts. We’re still having the film vs. video argument today, although now the two mediums are virtually indistinguishable from each other.

Because Anderson’s films very rarely have life or death stakes, the driving force and the emotional drama stems from the theme of family—specifically the threat of abandonment or loss. BOOGIE NIGHTS places this dynamic at the core of its story, presenting Horner’s filmmaking crew as a legitimate family, sharing in each other’s big life moments and cheering them on at weddings and awards shows.

Anderson also shows us how Dirk Diggler’s abandonment of his adopted family of pornographers leads to ruin. At the end of the day, he saves himself by crawling back in shame to Horner’s patriarch figure. In ending his story in this fashion, Anderson has created a prodigal son fable for the twentieth century. It’s a parable that illustrates the conceit that tragedy will ultimately befall those who choose to permanently turn away from family.

Anderson’s films often set their stories in his home state of California, and BOOGIE NIGHTS—perhaps more so than his other works—could not have taken place anywhere else but the Golden State. The San Fernando Valley, just north of Los Angeles, has served as the epicenter of the porn industry since its inception. Just like porn plays the redheaded, swept-under-the-rug stepchild to the Hollywood film industry, so too does the Valley sit offset from Los Angeles, stigmatized and dismissed because of its sleepy, suburban airs.

Like it or not, the porn industry is very much a part of southern California’s cultural heritage, so who better to paint its portrait than Anderson, the great cinematic recorder of California himself.

BOOGIE NIGHTS is also perhaps the most frank look at another of Anderson’s key recurring themes, that of sex dependence. HARD EIGHT and BOOGIE NIGHTS both flirt with sex as a paid profession: the former’s emotional tensions that stem from the troubles of Gwyneth Paltrow’s weary hooker Clementine contrasts with the latter’s celebration of sex on camera as an act of liberation and expression.

This also highlights a strange double standard when it comes to paid sex—the presence of the camera, for whatever reason, is the final arbiter between what is legal and what is not. The characters ofBOOGIE NIGHTS come to depend on their sexuality, as if it were a drug. Towards the end of the film, Dirk Diggler is back to where he started, reduced to jerking himself off in front of strangers for a couple bucks.

For others, like Cheadles’ Buck Swope, their past as porn stars hangs like a noose around their necks, impeding their progress in real world pursuits like starting a family or taking out a business loan.

BOOGIE NIGHTS caused quite a stir when it released, with high praise for prestigious film festivals like Toronto and New York leading to three Oscar nominations (one of which was a Screenplay nod for Anderson himself). The film was a breakout hit, its success arguably fueled by a bout of 70’s nostalgia that was pervading pop culture at the time. Thankfully, BOOGIE NIGHTS’ legacy has outshined the trends of it day, enduring to become one of the best films of its decade and ensuring Anderson’s future as a major new talent on the scene.

MUSIC VIDEOS & SHORTS WORKS (1997-1999)

During the period between the release of his breakout feature BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997) and his sprawling follow-upMAGNOLIA (1999), director Paul Thomas Anderson branched out into other forms of cinematic expression. He did what many filmmakers do between features to pay the bills: shoot commercials and music videos.

However, unlike other directors, it can be argued that he wasn’t exactly doing for-hire work. Almost all of his short-form work from these years can be tracked to some kind of investment in his feature work or his personal life.

MICHAEL PENN: “TRY”

For instance, his first music video was made for BOOGIE NIGHTS composer Michael Penn to promote his single “TRY”. The video was shot almost entirely in secret, with Anderson, Penn, and co-producer JoAnne Sellar stealing away during BOOGIE NIGHTS postproduction for a couple hours. They shot in what is allegedly the longest hallway in America, located in downtown Los Angeles. The video follows Penn in one long Steadicam take as he sings to camera and marches through various vignettes.

The piece is indicative of Anderson’s mastery of the camera and sense of movement, as well as his confidence with a Steadicam rig. Complex moves are pulled off with a dance-like grace that makes the entire piece look effortless. Anderson is known to be somewhat of a mischievous director, and “TRY” follows suit with a cameo by his close friend and collaborator, the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, as a slobby sound recordist.

FIONA APPLE: “ACROSS THE UNIVERSE”

The success of BOOGIE NIGHTS led Anderson into an echelon of celebrity that was previously unknown to him. He started dating singer/songwriter Fiona Apple, a relationship that birthed a small run of enchanting music videos. The first of these was for Apple’s cover of the Beatles’ “ACROSS THE UNIVERSE”, a track commissioned for director Gary Ross’ film PLEASANTVILLE (1998).

Anderson adopted PLEASANTVILLE’s black and white midcentury aesthetic for his video, albeit with a twist. Conceived as a series of long takes, Apple sings to camera while hooligans in letterman jackets trash a diner in slow-motion around her.

“ACROSS THE UNIVERSE” is a deceptively simple piece, with expertly-executed camera movements that give no trace of the complicated rigging and blocking required to achieve such shots. For instance, in the opening shot we track in directly on Apple, but we don’t see the camera in the mirror behind her (when common logic dictates we should).

The piece is filled with little “how’d they do that” flourishes like this, and like Michael Penn’s “TRY” before it, includes a cameo from one of Anderson’s repertory performers in the form of John C. Reilly as a suit stealing music from the jukebox.

FLAGPOLE SPECIAL

For 1998’s RET Inevitable 1 Festival in New York, Anderson was commissioned to make a seventeen minute short titled FLAGPOLE SPECIAL. The short apparently works as an indirect groundlaying for the Frank TJ Mackey character played by Tom Cruise in Anderson’s MAGNOLIA.

Based on a random conversation Anderson found on an old audiotape, FLAGPOLE SPECIAL was shot on digital video and features John C Reilly and Chris Penn riffing on their frustration with women and coming up with plans on how they would “Seduce and Destroy” them. As of this writing, it is publicly unavailable for viewing.

FIONA APPLE: “FAST AS YOU CAN”

In 1999, Anderson made his second music video for Fiona Apple, for her song “FAST AS YOU CAN”. It’s a much simpler piece, with Fiona performing straight to camera, locked into very precise compositions. While the video is straightforward and uncomplicated, Anderson does add various visual obstructions to the frame, like smudges and smears on the lens in a bid to make things a little more interesting.

FIONA APPLE: “LIMP”

Anderson’s third video for Apple covered her song, “LIMP”, and takes place in a dark mansion as a lovesick Apple roams the house, unable to sleep. The piece is full of the graceful, fluid camerawork that Anderson is known for, but he counters the elegance by chopping it up into a series of staccato, rapid-fire edits as the song’s intensity builds.

MAGNOLIA (1999)

During my senior year of high school, I spent a grand majority of my time in the halls of the campus’ performing arts center. The eclectic mix of creativity and awkward hormonal clashes was endlessly fascinating to me, no doubt because it reflected what was churning inside of me. Within the rigid and confining social structures of high school, it was the one place I could go where I could truly be myself.

Towards the end of my time there, the more literary-minded and illuminated types began talking earnestly about their love for this 1999 film called MAGNOLIA—I film I had never heard of. I even acted in a one-act play whose author made no attempt to hide how much it had been influenced by the film.

I never got around to seeing the film myself until my first semester at Emerson College, where I was introduced to director Paul Thomas Anderson’s work by way of BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997). When I finally sat down to watch MAGNOLIA, it became immediately apparent to me that I was watching a masterwork from a highly confident director who was wielding his camera with a degree of energy and power unlike anything I had ever seen before.

The runaway success of BOOGIE NIGHTS resulted in New Line Cinema gifting Anderson the opportunity to do anything he wanted as his next project. Knowing he’d never again be in this enviable position, Anderson decided to go for broke and make a passion project that he described as the All-Time Great San Fernando Valley film. In plotting out his story, Anderson tapped into great reservoirs of creativity and inspiration.

What started off as a small, off-beat character piece soon blossomed into an all-encompassing statement on loneliness, regret, and chance in a small patch of suburb just north of bustling Los Angeles. MAGNOLIA sees Anderson step ever more firmly into Robert Altman territory by weaving together several disparate threads and slowly pulling them taut to reveal a tightly-woven tapestry of life, love and loss.

Simply put, it is the magnum opus of the first phase of Anderson’s career, capping off a long fascination with sprawling ensemble-based stories.

The central conceit of MAGNOLIA is that the film’s story unfolds along a stretch of the titular street, located in the San Fernando Valley—purportedly all within a span of a few square miles. The idea is to communicate the range of humanity that can occur in such a small amount of space, and how we’re more connected than we think. At the center of the film is an awkward romance between Claudia Gator (Melora Walters), a nervous wreck of a woman who’s been hollowed out by excessive drug use and several emotional trauma.

After playing her music so loudly that the neighbors call the cops, she’s visited by John C Reilly’s Officer Jim Kurring—a gentle giant who finds in Claudia a beacon of hope and a potential cure for his romantic ailments. Claudia’s father, venerated game show host Jimmy Gator (Phillip Baker Hall), also tries to reach her, struggling to find some redemption from the sins of his past as he loses a fight with cancer.

A short distance away, Donnie Smith (William H. Macy), a former child genius and famous contestant on Gator’s game show, is struggling to hold on to his job at a local furniture outlet so he can pay for braces he doesn’t need, all to impress a male bartender that’s caught his eye.

As all of this is going down, an old man named Earl Partridge (Jason Robards) lies on his deathbed, attended to by his nurse Phil Parma (Phillip Seymour Hoffman). Earl’s wife Linda (Julianne Moore) storms about town trying to make her own wrongs right in the wake of the realization that only now has she come to actually love her husband.

And last but not least, there’s Frank TJ Mackey (Tom Cruise), Earl’s estranged son and a chauvinistic pick-up guru/artist hawking an allegedly “foolproof” seduction technique, bound for an emotional reckoning of his own.

As MAGNOLIA unfolds, all these story threads draw closer together; the major events rippling like waves through the narrative. Destiny has intertwined their fates. MAGNOLIA explores ideas about chance and coincidence, comparing them against a larger, pre-determined arc of the universe. In a move that’s both inspired and utterly baffling, Anderson uses a counterintuitive image to state his case: a random, inexplicable downpour of frogs, materializing as if from nowhere and hurtling towards the earth with biblical fury.

The film goes to great pains to suggest that these seemingly random events might just be the opposite, and that our fates may indeed by pre-ordained and unforeseeable as a sudden hailstorm of amphibians.

While an expanded budget allows for higher-profile actors, Anderson culled his cast mostly from his pool of BOOGIE NIGHTS alumni. Reilly, Walters, Hall, Macy, Hoffman and Moore all deliver some of their best work, thanks to an unwavering dedication to Anderson’s vision and an eagerness to play against type.

MAGNOLIA is perhaps the most definitive example of Anderson’s company of actors, featuring supporting performances from Luis Guzman as an irritable and impatient contestant on Jimmy Gator’s game show, Ricky Jay as the show’s producer and the omniscient narrator during the film’s prologue and epilogue sequences, Alfred Molina as Macy’s Persian furniture store boss, and even Thomas Jane as a young Jimmy Gator.

Of the new talent, Robards gives a heartbreaking performance in his final film role as a man besieged by regret at the end of his life, and Cruise was nominated for an Oscar in what is generally considered a career-best performance as the scene-stealing chauvinist who uses bravado and machismo to bury his crippling daddy issues. MAGNOLIA is the kind of film that lives or dies off of its performances, and thankfully the collective efforts of Anderson’s brilliantly-chosen cast helps the piece soar to exhilarating heights.

MAGNOLIA is not as visually stylized as Anderson’s previous work, but he still manages to achieve a larger-than-life feel thanks to returning cinematographer Robert Elswit’s virtuoso camerawork. The film’s aesthetic is textbook Anderson: a 2.35:1 anamorphic frame given vigor and color by a mix of confidently executed dolly, crane, Steadicam, and handheld compositions.

Like BOOGIE NIGHTS before it, MAGNOLIA uses long tracking shots to convey space and time, pulling its characters along their cosmic journeys. Elswit and Anderson find the opportunity to experiment with different film stocks and cameras in MAGNOLIA’s bookending “chance or fate” sequences—a highlight being Anderson’s use of an authentic, hand-cranked Pathe camera to simulate the look of old silent pictures.

With MAGNOLIA, Anderson’s regular editor Dylan Tichenor has his work cut out for him in keeping track of all these disparate story threads. If Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory established how editing could be used to tie two separate events into continuous time and space together, then Tichenor’s work on MAGNOLIA serves as the arguable evolution—interweaving the sweeping emotions of human experience into a cosmic tapestry.

Anderson and Tichenor’s edit plays like the film equivalent of a symphony, with harmonies and choruses organized into distinct movements. The movements themselves are distinguished via an inspired intertitle conceit that, instead of conveying the passage of time, notates changes in weather and humidity. It’s an interesting idea that we’ll certainly never the likes of again, further evidencing Anderson’s unique worldview.

MAGNOLIA is the first of Anderson’s features to not feature the work of composer Michael Penn, but he does retain musical continuity in Jon Brion and Penn’s wife, Aimee Mann. Brion’s score in particular is worth singling out, as he has created a brooding suite of orchestral cues that are at once both foreboding and elegiac, giving the necessary weight to the burden that Anderson’s characters must carry.

The score ducks and weaves through the piece, oftentimes playing against or running under diagetic source tracks from Mann and Supertramp. The effect is disharmonious, but in a good way, further solidifying the film’s mosaic conceits. Mann is a huge vocal identity within the soundtrack, providing several key songs such as the showstopping “Wise Up”. The song is incorporated in a strikingly original way, playing over a sequence in which the characters sing along to it, staged within their various individual vignettes.

The result is nothing less than one of the most unexpected and memorable moments in recent film history.

The medium of video plays a huge role in shaping Anderson’s worldview, like it does for several of filmmakers in his generation. However, his treatment of the format undergoes something of an evolution throughout his filmography. In BOOGIE NIGHTS, video was a disruptive, transgressive advancement that held malevolent implications for its characters.

By the present-day narrative of MAGNOLIA, video had become commonplace and commodified. Its power harnessed by people like Frank TJ Mackey as a sales tool— a slick, well-lit means to nefarious ends.

Mackey’s “Seduce And Destroy” operation is indicative of another of Anderson’s thematic fascinations, that of sex dependence. Mackey employs a tactical, scorched earth approach to seduction, viewing women purely as targets to be eliminated with the ballistics rocket below his belt. As his character arc plays out, it becomes quite clear that this militaristic, highly-disciplined and aggressive approach to sex is a crutch he leans on, a shovel to bury deep-seated rage about his past and his family.

Indeed, several of MAGNOLIA’s characters’ dramatic troubles stem from sex in some manner—Reilly and Walters’ fumbling romance, Robards’ abandonment of the love of his life for a fleeting affair, or Hall’s continuing infidelity and the implied sexual abuse of his daughter. MAGNOLIA’s thematic exploration of sex dependence overlaps with his exploration of family dynamics, digging deep into his characters’ insecurities and faults to find an inherent desire for the comfort of home and family.

Like any wildly ambitious film, people didn’t quite know what to make of MAGNOLIA when it was released. The film didn’t do well at the box office, but critics hailed it as a profound expansion of Anderson’s directorial skill. People were just as quick to deem it a masterpiece as they were to deride it as an overindulgent failure. Regardless, MAGNOLIA went on to considerable awards seasons success, winning the prestigious Golden Bear award at that year’s Berlinale as well as an Academy Award nod for Anderson’s screenplay.

Now that over ten years has passed, MAGNOLIA’s legacy as one of the 90’s best films is assured. It is an undeniable technical triumph, and a product of a confident virtuoso aesthetic that, for all its complications and flourishes, never loses sight of the big picture.

MUSIC VIDEOS & TV WORK (1999-2000)

With the release of 1999’s MAGNOLIA, director Paul Thomas Anderson had arguably reached the peak of what he could do with his particular stylistic conceits. As he developed ideas for his next feature project, Anderson dove right back into the world of music videos and short-form work as a way to keep his directorial skills active and engaged.

AIMEE MAN: “SAVE ME” (1999)

Like the music video for Michael Penn’s “TRY” following BOOGIE NIGHTS in 1997, Anderson created a tie-in music video for one of MAGNOLIA’s musical muse, Aimee Mann. The track, “SAVE ME”, appears during the closing scene of MAGNOLIA, and was written specifically for the film. To reflect his, Anderson and Mann settled on an idea that would recreate key moments from MAGNOLIA in motionless tableau form, while integrating Mann singing towards camera in the background.

Anderson’s fingerprints are all over this video, with a camera that continuously dollies forward on Mann with a creeping confidence. He also throws in a little visual variety by way of moving the furniture and set dressing around in elegant, almost impossible ways that reveal the hidden artifice of each vignette. “SAVE ME” is a simple, yet moving little music video—and arguably Anderson’s most popular.

FIONA APPLE: PAPER BAG (2000)

The turn of the millenium found Anderson and then-girlfriend Fiona Apple collaborating on a music video once again, this time for her song “PAPER BAG”. The video finds Apple performing at a bar inside of an expansive lobby, surrounded by little boys dressed as grown men. Anderson shoots wide to feature the location’s beautiful architecture, as well as to showcase elaborate old-school musical choreography.

The piece is again an instance of Anderson’s elegant camerawork, incorporating the same whip-pan technique that he made a motif of in MAGNOLIA.

SNL: “FANATIC” (2000)

By the year 2000, Anderson’s work began to shift away from the sprawling, dynamic style that had made his name and towards experimental explorations into comedy and other genres. The first of such projects was done almost as a lark– less of a serious, cerebral project and more of a fun diversion for him and his friends at Saturday Night Live. The piece is a spoof on MTV’s show “FANATIC”, where a mega-fan gets the chance to meet his/her object of worship.

Anderson recruits SNL cast member Jimmy Fallon as “Fanatic’s” overly-aggro host, who tracks down Anna Nicole Smith’s biggest fan (played brilliantly by Ben Affleck in a role that lets him eschew his romantic leading man persona and ham it up with a false set of horrible teeth and giant braces). While Anderson’s “Fanatic” is undoubtedly a fun little side-project, in an oblique way it still fits naturally amidst his larger body of work.

The handheld video format and the reality TV conceit echoes THE DIRK DIGGLER STORY’s presentation and comedic tone, while Affleck’s quest to make Anna Nicole Smith his mother echoes Anderson’s thematic explorations of family and the search for home.

THE JON BRION SHOW (2000)

During this time, Anderson’s regular composer Jon Brion was trying to launch a new music-oriented variety show, appropriately titled THE JON BRION SHOW. Brion was unsuccessful in finding a home for the show at VH1, so Anderson stepped in to finance and direct a new pilot. While three episodes were produced in total, only the one featuring the late Elliot Smith has been made publicly available.

THE JON BRION SHOW follows a pretty standard, generic variety show format, utilizing multiple video cameras to cover Brion as he guides us through the evening’s playlist. The piece is a very rough, yet fascinating look into Anderson’s interests outside of just filmmaking, as well as a nostalgic little time capsule of a very particular sound that flourished during the turn of the millennium.

While Anderson’s output during these years is relatively small, he was able to capitalize on the popularity afforded to him byMAGNOLIA’s modest success with a string of experimental works that allowed him to broaden his scope and expand his aesthetic.

PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE (2002)

By 2002, director Paul Thomas Anderson had gained a reputation for long, sprawling features with multiple points of view. He had arguably reached his personal apex with this style in 1999’s MAGNOLIA, and began feeling a desire to subvert his critics and move away from the types of films that had made his name. During interviews, Anderson began to vocally express his wish to make a short romantic comedy with Adam Sandler—a wish that was laughed off by most critics who knew of his mischievous nature.

So imagine their surprise when he actually follows through on his promise with 2002’s PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE, an off-the-rails romantic comedy inspired by the real-life story of a California man who exploited a loophole in a Healthy Choice/frequent-flyer promotion for personal gain.

On paper, a rabidly quirky Adam Sandler vehicle directed by an arthouse auteur would read as a surefire failure, but Anderson’s fourth feature finds him feeding off the energy of a particularly experimental phase, making for the shortest, most idiosyncratic (but also the most charming) film of his career.

PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE follows Sandler’s Barry Egan, a neurotic entrepreneur of novelty hotel plungers and a man prone to volatile emotional outbursts and crippling anxiety. Despite being surrounded by seven overbearing and suffocating sisters, Barry is a profoundly lonely man who takes a simple pleasure in running a modestly successful business.

One night, a misplaced yearning for human connection leads Barry to dial up a phone sex line, inadvertently exposing himself to a ruthless extortion scheme that thrives off the guilt of so-called “perverts” like himself. As he battles with fraud, he’s introduced to the calm yin to his powderkeg yang: a pretty Englishwoman named Lena (Emily Watson). She’s socially awkward like he is, and their off-kilter chemistry brings out an adventurous side to each other that they never knew they had.

On top of all this, Barry has also stumbled upon a loophole in a frequent-flyer promotion run by Healthy Choice that nets him an insane amount of airline miles at the cost of several pudding packs. Emboldened by his newfound love towards Lena and flailing rage at his fraudulent tormentors, Barry sets about collecting as many pudding packs as he can to rack up miles and take control of his life.

Sandler, one of the most polarizing figures in Hollywood, is rightfully vilified for his dumb, juvenile slapstick comedies. To the complete surprise of the stuffy film elite, Sandler’s performance in PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE turned out to be one of 2002’s best—his conveyance of a dark, complicated soul is routinely hailed as his finest hour.

Watson’s casting is equally inspired, her gentle eccentricities becoming the perfect foil to Sandler’s tenuous grasp on his temper. The reliable stock company of actors that Anderson had cultivated in his previous three features is largely absent from PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE, save for the late, brilliant Philip Seymour Hoffman as the cocky sex-line extortionist and Luis Guzman as Barry’s loyal, if somewhat dimwitted, business partner.

Much like the title suggests, PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE is a strange brew of discordant influences and tones, taking conventional rom-com tropes and filtering them through Anderson’s unique worldview. Cinematographer Robert Elswit returns to lend some visual consistency to an otherwise-radically different project for the director.

The pair continues their use of the anamorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio, as well as dynamic Steadicam camerawork and bold, deliberate compositions. Anderson also builds upon his core aesthetic with several expressionistic visual abstractions, like unmotivated lens flares, harsh highlights, silhouettes, and animated watercolor-painting interludes courtesy of video artist Jeremy Blake.

Production Designer William Arnold also returns, creating a bright, yet drab, every-world for the characters to inhabit. Arnold utilizes a red, white, and blue color palette to convey Anderson’s curious vision. A film’s color palette should be an active participant in telling the story, and Arnold’s work accomplishes it with a minimum of fuss.

The white, colorless walls of Barry’s apartment and warehouse suggest a bland, directionless existence, so when Barry shows up in a bright blue/indigo suit, the act is indicative of Barry opening himself up to the potential of excitement and change. Watson’s Lena appears primarily in a bright red dress, nicely complementing Barry’s own wardrobe with the color of passion—a passion that will fully consume Barry and give him the necessary courage to overcome his obstacles.

Anderson’s musical choices also mark a direct shift away from his past work while still maintaining a degree of continuity. He retains the services of composer Jon Brion, who utilizes the distinctive sound of the harmonium to create a discordant electronic sound that bubbles furiously and echoes Barry’s severe internal stress. Indeed, watching PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE can be a very stressful watching experience, mainly due to Brion’s jittery, unrelenting score.

Want To Learn From Oscar® Winning & Blockbuster Screenwriters?

Learn from some the best screenwriters working in Hollywood today in this FREE three day video series.

Instead of the wall-to-wall jukebox approach that Anderson employed in his previous films, Anderson employs a much more disciplined approach to his needledrops. He limits them to just one: Harry Nillson’s “He Needs Me”, a rather strange little ballad that captures Anderson’s darkly whimsical tone and becomes the de facto theme song to the piece. PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE is the end of an era for Anderson, with the film being his last collaboration with Brion (as of this writing).

In Anderson’s subsequent hiatus from filmmaking during mid-2000’s, Brion became one of the unfortunate casualties of the director’s artistic reinvention. I don’t imagine that this could be attributed to bad blood between the two, but rather an amicable parting of ways as the result of Anderson’s evolution of style requiring a sound far different than what Brion could deliver.

Despite creating such a radical stylistic experiment for himself, Anderson can’t help but incorporate his major thematic fascinations into PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE’s story. The film is fundamentally a love story, and love stories are fundamentally about the search for a mate—- with the creation of a family being the larger implication. Barry’s search for a mate, personified in Lena, is a way for him to escape his own family of seven emasculating sisters and become the head of a new one.

PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE’s love story also serves as a convenient conduit for Anderson to explore ideas toward sexuality by way of Barry’s varied responses to his newfound feelings. He confuses sex for love, initially trying to alleviate his loneliness in the companionship of a phone-sex line girl. Their conversation is hollow and transactional despite being laced with aggressively sexual dirty talk.

Contrast that withBarry’s wooing of Lena, a dynamic that is almost child-like in its innocence while simultaneously providing a profound, intimate connection and a foundation for love to flourish. Anderson’s love of California iconography and culture is also present, albeit in a subdued form that accurately conveys the colorless palette of the San Fernando Valley’s suburban/industrial outskirts.

A distinct step away from the kind of films people loved him for, PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE was a bold gamble for Anderson—a gamble that ultimately paid off when critics hailed Sandler’s performance as one of the best of the year and awarding Anderson himself with the Best Director prize at the Cannes Film Festival. While not his best-known film, PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE has attained a cult following that’s kept it within cinema’s collective consciousness.

It may be minor in terms of impact and scale, but PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE is a major shift towards a new phase of Anderson’s career and in-depth character studies that continue to this day.

ANDERSON’S SHORT WORKS (2002-2006)

After the release of 2002’s PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE, director Paul Thomas Anderson embarked on a little hiatus from feature filmmaking that would last for five years. While he decided on what he wanted to develop as his next project, he took on several small-scale projects to keep his skills sharp and his creativity active.

BLOSSOMS & BLOOD (2002)

Several of Anderson’s works from this period are conceptually supplemental to PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE and his collaboration with Adam Sandler. When tasked to find a purpose for his feature’s deleted material, Anderson decided to forego the conventional route of including them as DVD bonus content.

Instead, he whipped several of his leftover elements into a self-contained mood piece called BLOSSOMS & BLOOD. The piece is an artfully-blended mash of deleted scenes, video artist Jeremy Blake’s animated paintings, and the music video for composer Jon Brion’s single “Here We Go”. BLOSSOMS & BLOOD utilizes flares of color and light, as well as a disorienting, experimental sound mix to reflect the abstractly-whimsical tone of PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE.

Freed from the demands of feature-length storytelling, Anderson is able to crank this particular aesthetic into overdrive, giving us a glimpse into Barry Egan’s inner madness and rapture.

MATTRESS MAN (2002)

The production of PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE spurred another set of works for Anderson, and while they are tangentially influenced by the feature, they aren’t as directly intertwined with it as BLOSSOMS & BLOOD is. In 2002, the internet was just beginning to take off as a forum for short-form video exhibition.

Anderson, perhaps consciously or not, took advantage of this nascent technology by releasing a trio of very small sketches based around a singular, slap-sticky joke.

The first, MATTRESS MAN, sees the late Philip Seymour Hoffman reprise his sleazeball character from PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE filming a commercial for his mattress retail business. The piece is filmed in analog video to emulate the homegrown, lo-fi nature of regional retailer commercials.

Aside from being hilariously entertaining in the span of a single minute,MATTRESS MAN is valuable within Anderson’s body of work in that it continues his exploration of video as a medium. Whereas MAGNOLIA’s (1999) Frank TJ Mackey character employed slick, well-lit video to sell his “Seduce & Destroy” technique, MATTRESS MAN shows us how in a different set of hands, video can come off as inept and clumsy.

BALLCHEWER (2002)

The second piece from this period is BALLCHEWER, which also appears to have been shot during the production ofPUNCH-DRUNK LOVE. It features Anderson regular Luis Guzman and PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE’s Emily Watson interacting with a pitbull. Curiously, this piece looks to have been shot on film in Anderson’s signature anamorphic aspect ratio, leading one to believe it might have been shot on a lark at the end of one of the feature’s shooting days.

The punchline toBALLCHEWER is oblique and a little muddy, making it the weakest of the trio.

COUCH (2002)

The third and final film of the trio, COUCH, continues Anderson’s collaboration with Adam Sandler, who plays a man trying out new furniture at his own peril. The piece is shot in black and white, and told mostly in silence except for exaggerated sound effects.

None of Sandler’s restraint or nuance from PUNCH-DRUNK-LOVE is present here. Instead, Anderson lets Sandler go full-on clown mode, creating a dynamic that feels distinctly out of place with Anderson’s aesthetic. Together, these three sketches form a triptych exploring the fine line between lowbrow slapstick and highbrow art—a conceptual investigation whose promise Anderson ultimately mined better in PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE.

DEMO JAIL (2006)

Anderson was largely absent from the scene during 2003-2005. His first child (with comedienne Maya Rudolph) was born in 2005, and the same year he served as the standby director on A PRAIRIE HOME COMPANION, directed by his hero Robert Altman (who was ailing in health and was obligated to hire someone to replace him in the event of his death for insurance purposes).

Needless to say, big things were happening in his life that necessitated a short break from his career. By 2006, Anderson’s productivity began picking back up, beginning with a short sketch he directed for (the short-lived) THE SHOWBIZ SHOW WITH DAVID SPADE called DEMO JAIL.

The piece riffs on an old joke within the entertainment industry—that of the wanna-be who forces his awful demo on an established and successful friend. David Spade naturally plays the successful friend, who is trapped inside his intern’s car and forced to listen to the same terrible song again and again.

Shot on video, the sketch itself isn’t particularly good, with nothing in its execution to suggest Anderson’s hand. All in all, it’s rather forgettable, but it does serve as a warning shot for Anderson’s career comeback the following year with his staggering epic, THERE WILL BE BLOOD.

THERE WILL BE BLOOD (2007)

The year 2007 was a very special year in cinema for me. On a personal level, it marked the tenth anniversary of my own first short films, an occasion I celebrated with a limited engagement of a feature I co-directed at a local Portland arthouse theatre.

On a wider scale, 2007 saw the release of three of my favorite films of all time (NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN, ZODIAC, and THERE WILL BE BLOOD), by three of my favorite directors (The Coen Brothers, David Fincher, and Paul Thomas Anderson respectively). Now that we’re some years removed, these three films are generally considered to be among the very best films of that decade.

Watching these films was a religious experience for me; I could only imagine that this was what it must’ve felt like to take in the first screenings of films from the French New Wave of the 60’s or the American crime dramas of the 70’s.

It was the height of a very special time in cinema, where visionary auteurs found homes for their passion projects in specialty studio shingles like Focus Features or Fox Searchlight. The aforementioned three films represented the apex of this movement, and were the culmination of an unsustainable model that would cause the whole house of cards to come toppling down only a year later (an implosion I would unwittingly experience firsthand during my internship at Warner Independent Pictures).

Out of these three pictures, THERE WILL BE BLOOD cut through to affect me on the most fundamental level. My initial impression of the film was that it was a staggering achievement—I walked away convinced I had seen the modern equivalent of CITIZEN KANE (1941), and that a new contender for “best film of all time” had just been christened.

Time has softened my hyperbole, but my conviction remains—THERE WILL BE BLOOD will stand the test of time as one of the greatest films ever made. THERE WILL BE BLOOD’s conception was something of an unexpected lark. After the release of 2002’s PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE, director Paul Thomas Anderson was out of the public eye for five years, undergoing lots of personal and artistic growth, building his family, and finding inspiration from unlikely places as fan anticipation for his next project grew to a fever pitch.

While experiencing a bout of homesickness during a trip to London, Anderson purchased a copy of Upton Sinclar’s novel “Oil!”, mainly because he liked the image of California oil fields on its cover. Transfixed by the novel’s cinematic potential, he began pulling further inspiration from the biography of real-life California oil tycoon Edward Doheny and John Huston’s classic 1948 film THE TREASURE OF SIERRA MADRE (which he watched nightly).

He gave his project the lurid title THERE WILL BE BLOOD, constructing it as his own version of the great American epic—a grand statement on capitalism and the perversion of all-consuming ambition, embodied by one of the most original and compelling antiheroes in cinematic history.

In turn of the century Bakersfield, California, ruthless oil tycoon Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis in a career-defining, Oscar-winning performance) is very rapidly accumulating wealth from his growing oil enterprise. Along with his adopted son HW Plainview and business partner Fletcher (Ciaran Hinds), Plainview negotiates the purchase of the Sunday Family homestead, located in the barren deserts of a village called Little Boston.

Unbeknownst to the Sundays, the land has an ocean of oil underneath it, just waiting to be drilled by Plainview and his cohorts. His supremely profitable enterprise brings unprecedented growth and prosperity to the inhabitants of Little Boston, turning it into an overnight boomtown.

However, success has its dark side, which Plainview learns as he grapples with Sunday’s son, Eli (Paul Dano)—an aspiring evangelical preacher who extorts Plainview into building a church for him and his flock. The two viciously lock horns in a battle that pits capitalism against theocracy for the soul of Little Boston.

Anderson has painted in THERE WILL BE BLOOD a dark portrait of greed, corruption and power that forces us to confront the ugliest aspects of our American ideals. Day-Lewis’s portrayal of blackhearted Daniel Plainview possesses shades of Bill The Butcher from Martin Scorsese’s GANGS OF NEW YORK (2002), only more intelligent and sophisticated in both temperament and taste.

He simply looms larger than life, and in the process becomes a legendary screen villains on par with Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula or Heath Ledger’s Joker. As Plainview’s ideological foil Eli Sunday, Dano could have very easily been overshadowed by his co-star’s scene-shredding gravitas.

Fortunately, Dano more than holds his own with an amazing performance as a vain, manipulative so-called Man of God whose intentions are just as slimy as the “devil” he endeavors to destroy. THERE WILL BE BLOOD focuses mainly on the duel between these two unconventional titans, thus eliminating the need for Anderson to recruit any of the members of his personal acting company. Working with a suite of fresh new faces, Anderson’s focus is invigorated.

Despite the changing of the guard in front of the camera, Anderson still relies on most of his usual technical collaborators: producers Daniel Lupi and JoAnne Sellar, editor Dylan Tichenor, and cinematographer Robert Elswit who won the second of the film’s two Oscars for his stunning work.

Anderson’s preferred 2.35:1 aspect ratio is perfectly suited to capture the dusty, earth-toned vistas and sweeping, confident camera moves. While Anderson’s visual language doesn’t change physically, the dynamic of its intentions has.

Elaborate camera moves project a grand scale that evokes the work of John Ford and John Huston and lends the picture an overall air of myth. The grandeur is almost overwhelming, and would risk coming off as supremely pretentious in the hands of a less-capable director. Thankfully, Anderson’s confidence and mastery of his craft assures the tone attains the right balance of gravitas.

Anderson scores a new collaborator in production designer Jack Fisk, who had already become a legend in his field for his work on Terrence Malick’s films. With THERE WILL BE BLOOD, Fisk does what he does best: bringing an authentic, lived-in period vibe designed to place us firmly in the time and place of the story. Fisk’s attention to detail is truly incredible—everything falls within Anderson and Elswit’s established color palette, and nothing rings as false or out of place.

Anderson’s reinvention of his visual aesthetic extends to the music, where he finds an inspired, creative refreshment in his collaboration with Radiohead guitarist Johnny Greenwood. The music in Anderson’s films have always erred on the side of quirky, but in THERE WILL BE BLOOD the musical character shifts from Jon Brion’s curiously endearing compositions to something more classical and avant-garde.

Greenwood uses harrowing, discordant strings to pervert the conventional orchestral sound into a droning echo of Anderson’s portrait of brutal capitalism. Anderson supplements Greenwood’s compositions with classical source cues like Arvo Parte’s Fratres suite or Brahm’s Violin Concerto in D Major, creating a distinctly Kubrick-ian vibe.

At the center of the film is a tense dynamic between Plainview and his adopted son HW, a precocious and intelligent little boy whose increasing rebelliousness earns him a one-way ticket to an expensive boarding school far away. The elder Plainview is too consumed by his drilling operation to properly raise his son, and in the process inadvertently turns his little business partner into a competitor.

Anderson’s career-long exploration of family dynamics takes a left turn in order to reflect Plainview’s empty soul. Plainview uses HW to project the appearance of an affable family man, even as he takes over people’s land and robs them of their potential fortunes.

In eschewing a conventional plotline or story-arc, the emotional climax ofTHERE WILL BE BLOOD hinges on this tension between Plainview and HW, which comes to a head when HW is a grown man and expresses a desire to move to Mexico with his wife and start an oil company of his own.

Plainview sees this as an act of betrayal and rejects HW as his heir while revealing his true lineage. It’s a pitiful power play that affords Plainview a temporary, petty victory, but it’s clear to the audience that he’s damned himself to a short-lived future of loneliness and regret.

In Anderson’s eyes, tragedy ultimately befalls those who choose to permanently turn away from family. Plainview’s ultimate tragedy is that for all the material wealth he could accumulate, he would always be emotionally and ideologically bankrupt and didn’t have the wherewithal to recognize it.

Anderson’s other thematic fascinations are present in THERE WILL BE BLOOD, albeit in surprising ways. His stories and characters are inherently Californian in nature, meaning that they always reflect some aspect of the Golden State’s rich cultural heritage.

The oil boom that fueled the rise of cities like Los Angeles is depicted here during its infancy (however, the film was shot, ironically, far away from California in Malta, Texas). The fields of steadily-rocking oil derricks profoundly shaped California’s geography and culture, and one need only to look at the expansive oil fields of LA’S Baldwin Hills to see that oil continues to drive California’s economy to this day.

THERE WILL BE BLOOD’s true genius is in its understated relevancy to our modern age, and how our actions can reverberate over the course of a century. Despite all of our technological advances and progress as a society, we’re still down there in the muck, bludgeoning our way to prosperity.

Anderson’s filmography is greatly interested in sexuality and the human dependency on it. THERE WILL BE BLOOD is notable in this regard for its curious omission of all sexuality. Plainview is driven purely by greed, and hasn’t the slightest care of what other people think of him, much less the opposite sex.

Even the process of obtaining a son comes to him by way of something resembling more of a business transaction than the result of a sexual act. The absence of Plainview’s sexuality in itself is a profound comment on the intricate relationship between ambition and sexual longing, and how non-sexual pursuits like wealth and power can still be fetishized and obsessed over.

Need Sound Effects for your short or feature film project?

Download 2000+ sound effects designed for indie filmmakers & their projects for free.

Anderson’s classical, formalist style had been used to subversive effect in his previous work, but his full embrace of it inTHERE WILL BE BLOOD points to his maturing into a very different kind of filmmaker, one whose work is infused with an almost Orwellian sense of self-aware importance (oftentimes mistaken for pretension).

The palpable influence of Robert Altman, Jonathan Demme, and Martin Scorsese in previous films gives way here to the unimpeachable greats—John Huston, Stanley Kubrick, John Ford. As a whole, THERE WILL BE BLOOD feels very Kubrickian, its opening prologue running for a full twenty minutes before the first line of dialogue is spoken (a surefire nod to the Dawn of Man sequence in Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968)).

This choice doesn’t come from a desire to deliberately emulate Kubrick, however—instead it comes from a place of supreme confidence in Anderson’s skills as a visual storyteller. In seeing Plainview doggedly persist against a series of debilitating mishaps to get his first oil well up and running, we learn more about the ruthlessness and intelligence of the character far more than a dialogue scene could ever tell us.

Of course, Anderson’s knack for memorable and striking dialogue continues to be put to incredible use here. While there’s less of it, Anderson manages to concoct some of the most-quoted lines in recent film memory. The film would’ve been legendary enough even without the inclusion of Plainview’s “I Drink Your Milkshake” monologue, but its inclusion brings Anderson’s full vision over the top and into the territory of unimpeachable greatness.

THERE WILL BE BLOOD was hailed as a masterpiece when it was released, with critics praising its metaphors for a modern-day thirst for oil, an unquenchable commodity that is widely believed to have driven us into a needless war with Iraq under President Bush.

It is arguably Anderson’s most successful film, with a wide swath of nominations at that year’s Academy Awards (and two wins, but none for Anderson himself). Anderson dedicated the film to the memory of his hero Robert Altman, and in doing so, he closed the book on the first part of his career—a career that Altman had directly influenced—and began an exciting new one, marked by laser-focused character studies and a sense of grandeur unmatched by any other filmmaker working today.

THE MASTER (2012)

It’s symptomatic of a high-concept, tentpole-driven system of studio filmmaking that even one of our most treasured directors must struggle to find funding, despite an unbroken string of critically acclaimed works to his name.

After the collapse of specialty studio shingles like Paramount Vantage and Warner Independent Pictures who had churned out dozens of dramatically rich prestige pictures (albeit admittedly calculated to snag Oscars) during the mid-aughts, directors like Paul Thomas Anderson suddenly found themselves shut out from a Hollywood game that increasingly favored mindless popcorn fare.

For Anderson in particular, his long-percolating idea about a religious cult inspired by L. Ron Hubbard’s Church of Scientology was deemed too risky of subject matter for its asking budget. Anderson and his regular producers, Daniel Lupi and JoAnne Sellar, struggled to find funding for nearly five years, a fact made all the more excruciating because his previous film, THERE WILL BE BLOOD (2007), had generated some of the best reviews and press of Anderson’s career.

For a long while, Anderson’s highly-anticipated project, known by various names asTHE UNTITLED PAUL THOMAS ANDERSON PROJECT and THE MASTER, looked like it would never see the light of day. Enter: Megan Ellison, a hotshot twenty-something heiress with a love for visionary auteurs and their work, as well as the considerable financial resources to help make them.

In an industry increasingly paralyzed by risk and creative bankruptcy, bold figures like Ellison represent a beacon of hope that art and commerce don’t necessarily have to be separate from one another. Drawing further inspiration from LET THERE BE LIGHT (1946), John Huston’s World War 2 documentary about soldiers and PTSD, Anderson centers THE MASTER’s focus on Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix)—an eccentric, unstable man whose condition was amplified by the shell shock he contracted during the Pacific Theatre of WW2.

reddie can’t hold a steady job, is obsessed with sex, and is slowly drinking himself to death with a potent brew of whiskey, paint thinner, and torpedo fuel. In a drunken stupor, he wanders onto the yacht of a fatherly middle-aged man named Lancaster Dodd (Phillip Seymour Hoffman), who is revealed to be an enigmatic and charismatic scholar as well as the figurehead of a new religious following known simply as The Cause.

Freddie and Lancaster share a curious attraction to each other, with Lancaster tickled by the sense that he and Freddie have met once before—perhaps in a past life. Freddie uses Lancaster’s hospitality to ingratiate himself into The Cause’s good graces and inner circle, eventually earning himself a spot as a Lieutenant and Lancaster’s right-hand man.

THE MASTER defies narrative convention in that there’s no traditional story arc for audiences to follow. Instead, Anderson lets the story unfold in a compellingly obtuse way that highlights the leads’ off-kilter orbit around each other.

The result is a strange hybrid combining the starkness and gravitas of THERE WILL BE BLOOD with the eccentric abstraction of PUNCH-DRUNK LOVE (2002). There’s no condemnation of Scientology to be found here, like many had simply assumed or believed before seeing it—instead, Anderson’s vision is a portrait of a deeply disturbed individual finding his place within a community.

It just so happens that the “community” also happens to be a cult. The character of Freddie Quell is played with rapturous abandon by Phoenix in his first major role since his staged breakdown-as-performance-art seen in Casey Affleck’s I’M STILL HERE (2010).

He crafts a haunting, Oscar-nominated depiction of a man ravaged by war and self-abuse, commanding our undivided attention in every frame while fully immersing himself in his character (much like Daniel Day-Lewis had done in THERE WILL BE BLOOD).

Likewise, the late Hoffman was nominated for an Oscar in his last collaboration with Anderson before his untimely death in early 2014. Due to his long, rich working history with Anderson, Hoffman had the benefit of the role being written expressly for him, making for an effortless performance that projects a paternal warmth and convincing gravitas.

As one of the last roles of his career and life, Hoffman’s quiet, authoritative presence and un-showy confidence proves why he was considered to be one of the best, if not the best, actor of his generation. And last, but not least, Amy Adams plays Peggy Dodd, presenting a warm, matronly front as Lancaster’s wife—but behind closed doors, she’s more calculating and manipulative than Lady MacBeth.

In a film devoted to the two titan performances from its male leads, Adams more than holds her own, ending up with Oscar nomination herself for the trouble. Anderson’s regular cinematographer, Robert Elswit, was unavailable to shoot THE MASTER, so the auteur enlisted the help of Mihai Malaimaire Jr—currently making a name for himself as Francis Ford Coppola’s go-to cameraman.

The visual style of Anderson’s sixth feature is starkly different from what came before, the chief difference being Anderson’s choice to shoot the picture on 65mm film, making it the first feature to utilize the format since 1996.

This decision informed every subsequent choice down the line, meaning Anderson couldn’t shoot in his preferred anamorphic aspect ratio, and that the 65mm film camera’s sheer bulk limited his ability to execute his signature, dynamic movements.