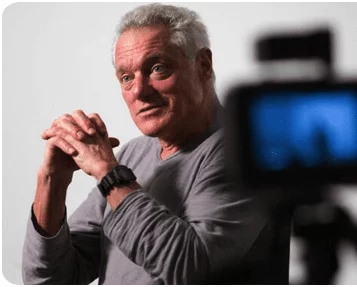

Sometimes the most unexpected turns lead us to our true calling. On today’s episode, we welcome Clarke Scott, an Australian writer, director, and commercial photographer who stepped away from academia and corporate life to pursue the art of filmmaking. His path wasn’t straightforward, but out of its twists and setbacks emerged a filmmaker determined to carve his own way.

Clarke first discovered filmmaking while burned out in the Himalayas, working on a PhD in philosophy. A chance encounter with a cinematographer shooting a documentary on the Dalai Lama introduced him to the DSLR revolution that was reshaping independent film. It was a moment of revelation. Filmmaking offered a space where creativity and technical craft could coexist — a marriage of his artistic roots in music and poetry with his love of technology and problem-solving.

That spark led Clarke to build a career from the ground up, beginning with corporate and industrial video before turning toward narrative film. Eventually, he wrote, directed, shot, and edited his first feature, 1000 Moments Later, a completely independent production. He described the film as both an artistic challenge and a practical choice — an opportunity to create a story that meant something to him while gaining the hands-on experience of every stage of production. “At some point, I decided I wasn’t going to rely on anyone. I will do everything,” he said.

Throughout our conversation, Clarke emphasized the realities of working outside Hollywood. He spoke openly about choosing not to move to Los Angeles, even when the chance was there, because he knew it would mean compromising his creative voice. Instead, he focused on what he could build in Australia, working with limited budgets but maintaining full control over his vision. For him, the long game mattered more than short-term industry approval.

He also shared the lessons learned on set. One story in particular stood out: a difficult scene that stretched over two days, with weather turning stormy and an actor struggling to hit the right emotional note. Frustration ran high, but in the end, the raw energy of the struggle — combined with the dramatic backdrop of the storm — elevated the performance. Clarke’s eye for adapting to circumstance became as important as his direction, a reminder that resourcefulness is often the hidden key to independent filmmaking.

Beyond the anecdotes, Clarke offered hard-earned advice for filmmakers navigating the realities of the industry today. He warned against chasing unrealistic dreams of festivals like Sundance as a financial plan, urging instead a focus on building a body of work, finding an audience, and learning every part of the process. In his view, the strongest path forward is to create work that proves both your creative vision and your ability to finish what you start.

His approach is clear: use the tools available, leverage your community, and never wait for permission. Whether that means borrowing locations, persuading actors to work for back-end deals, or using today’s digital platforms to self-release, Clarke believes filmmakers have more opportunities than ever to make their work seen — if they are willing to do the hard work themselves.

In the end, Clarke Scott leaves us with a portrait of a filmmaker committed to telling stories his way, on his terms. His journey is proof that determination, creativity, and adaptability can turn even the smallest production into something meaningful.

Right-click here to download the MP3

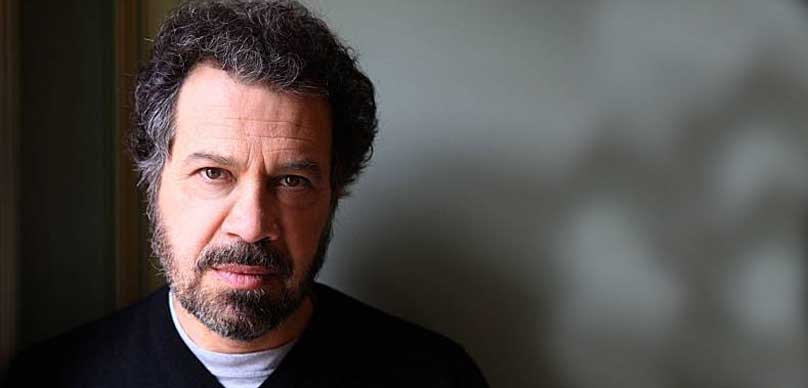

Alex Ferrari 1:49

Enjoy today's episode with guest host Dave Bullis.

Dave Bullis 1:54

On today's episode. Clarke is an Australian writer, director and commercial photographer. He just recently shot his first feature film, 1000 moments currently in post production. So here we go with Clarke Scott. Hey, Clarke, thanks a lot for coming on the show.

Clarke Scott 2:11

My pleasure.

Dave Bullis 2:12

So Clarke, I wanted to ask, you know, it's a question I always ask everybody, and that is your background in filmmaking. So you know, I wanted to ask, you know, what brought, brought Clarke Scott into the filmmaking world?

Clarke Scott 2:26

Do you want the long answer or the short answer Dave?

Dave Bullis 2:29

I will take the long answer along the long answer.

Clarke Scott 2:32

All right, so it's actually pretty long. I will. I'll go backwards. How's that sound? So I'm currently in post production on my first feature film called 1000 moments later. It was a tiny, little independent movie that I shot, I wrote, directed, shot. I'm doing the editing. I'm doing basically everything other than acting. And that came about because I'd spent a couple of years writing and trying to get projects up through to the point where I'd had producers reading scripts, and I'm from Australia, from Melbourne, but I'd had, I'd had a guy in LA looking at some of my work and things, it was just difficult. Things fell through. So I pulled the plug because it was just moving too slowly for me, and that's where the film came about. Filmmaking prior to that, I'd worked in kind of commercial, corporate video, industrial video, and for about six years. So the whole filmmaking thing came about because I was, we're going to remember, I'm going backwards in time, right? So 2010 I'm doing a PhD. I'm in the hills of the Himalayas. I'm totally burnt out. And the PhD was in philosophy. So I was taking a 14th century Tibetan philosopher and his notion of the self, and parsing that via six Western philosophers, including John Locke, David human for those interested, the American Constitution was actually came from John Locke's political philosophy so, and he was a British guy. I'm not sure how many of you American listeners would know that. I had no idea. But I was burnt out, and so I was walking through the the foothills of the Himalayas, and I was in a place called Dharamsala, that's where the Dalai Lama lives. And I came across a guy with what turned out to be a Canon 5d, Mark Two, and he was from LA. He was a small time DP, he was shooting a documentary on the Dalai Lama. And I stopped as you. Do like this. It's the Himalayas. There's no one around. It's like, dude, who are you? You know, what are you doing here? So we got to chatting, and that kind of opened up a whole new world to me. Philip Bloom, Vincent la Ferrari, the whole 5d revolution was taking place at that very point. So it was, I don't know, might have been oh nine, so I was perhaps a little late. I think the was it the five to mark to come out in oh eight. I think I can't remember anyway. And so when I say it opened up a whole new world, it? It? It was a whole new world for me, but it was also a reconnection with my past and where I'd come from. So as a young bloke, I went to music school, a prestigious Music School in Melbourne called Victorian College of the Arts. And at the time it was, it was like Juilliard in a lot of ways, and I was kind of earmarked for a career in that so I was from a young the time of a teenager, young teenager. I was doing all kinds of things. I was designing my own my own clothing. I was playing in rock bands, I was writing poetry, and I was a very creative kid that kind of got knocked out of me through life. So just I guess, following the advice of people who I shouldn't have they they hadn't been their best. They had my best intentions in mind, but they wanted me to do something that just wasn't right for my personality. So between the PhD and this kind of creative phase of my life, where I was at music school, there was a phase where I was doing web development and I'd taught myself to code, and I kind of got into a whole corporate world, but that that I got burnt out by that, and I'd had a love of philosophy all at the same time, so I thought that rather than continuing on in it, I'd go and do a PhD and then perhaps go into academia. And that kind of didn't work because it didn't really suit my personality. So when I, when I came along and found this DP from LA with a Canon 5d and then through that, going onto the internet and seeing Phil blooms work and Vincent la Ferrari his work, my mind was blown. And what it what it did allow me to do is it allowed me to couple my love of being creative with the kind of the geeky aspect of filmmaking in so filmmaking can be quite technical, and there's the Whole gear thing. So marrying those two plus, I really wanted to create stories of the told stories of human potential, something that that I'm keenly interested in, and something that I pursue in my own life. But it helped me, and what 1000 moments later in in essence, is actually about it's an exercise in that. It allowed me to do that, but also have a career where I could feed my family. So if that, the way I looked at it was, if I go ahead and I stop my PhD, and I start this other thing, and I there's a whole bunch of things that I have to learn at the if all of that fails, at least I've got skills that someone can employ me for. I can I can learn editing, and I can go off and earn money cutting shitty corporate videos. And actually, that's what happened for the first couple of years. So that's, that's kind of, that's the that's the verbose version Dave.

Dave Bullis 9:07

I will always choose the long version if I ever get the option, because I always find the long version always includes a lot of, you know, interesting tidbits and side roads that I always find fascinating. Because I find one thing that happens to a lot of us in this industry is it's not a clear path from A to B. Usually it's from like a to b. You have to go through all the other letters of the alphabet and then come backwards, and then come through, and then you can get to from A to B, you know, stuff like, you know, when you were just saying about learning side going into the side jobs and and doing all the corporate work and stuff like that. That's what happened to me. I actually went into academia, and I ended up teaching classes that I wasn't getting paid for. I ended up, you know, and then finally, you know, you get burned out. And finally, April of this year, I had to leave because I was like, this job is literally. I am living and breathing it, yeah, and I could never get away from it,

Clarke Scott 10:14

Yeah, yeah. I was surprised, actually, when I went into the whole world of academia, I was two things, I was surprised by, actually three. They worked incredibly hard for not a lot of financial return, like, you know, some of my professors 8090 hours, and they were earning not a lot of money. And that, that may be an Australian thing. I don't know what it's like in the US, but the politics, and because of that, the politics that that kind of environment fosters, meant that that and these people aren't sages, they're not Bodhisattvas. They're not, you know, their lives aren't embedded in notions of compassion. Some of them are, but a lot of mad. So there's a lot of kind of there was a lot of backstabbing, I guess, just a lot of politics. And I was really surprised by that. So the fact that I burned out and didn't finish, I'm it's a regret. I would have liked to have finished, but even if I had, I would not have gone into into into us. I was going to say politics. I wouldn't have gone into academia.

Dave Bullis 11:21

Yeah, where I worked, a lot of politics, it was a smaller school, and it was just some of the professors would, I mean, I'll give you an example. There was a multimedia professor who who taught editing, who knew nothing about editing. He would literally just send them to me, and never asked me about it. And he would just say, hey, go talk to Dave. And you know, he'll help you out. Well, finally, I'm like, you know, why are all these people coming to me? And then they would say, well, all the students would say, Well, you know, Dr blah, blah, blah told us to go talk to you. And meanwhile, he's at home, you know, having dinner with his family, and I'm down there teaching editing. And you know, you complain to people and nobody cares. It's a shame, I but I think academia, at the most part, has pretty much been eroded over the years because of that, because of the political game, but be also because there used to be where they'd be working professionals, and they would be, you know, they get their bachelor's, go out into the real world at the same time, work on their masters, and then they would come back and maybe get that PhD and then start teaching at the same time to start in the real world. I don't think they do that anymore, at least for the most part. At least I don't see that is, I think it's basically they get their bachelor's, they jump on board as a TA or something, working inside the school, get their masters and do the same thing for the PhD. So they have no real world skills, but they have a lot of very fancy degrees and that. I think that's the problem, and I think that's the reason they play the political game, because anybody who's better than them immediately has to be taken out, because otherwise, what do we need this guy for?

Clarke Scott 12:55

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I think Australian academia is probably a little bit softer than that. That's does not sound like an enjoyable environment to work. So, yeah,

Dave Bullis 13:08

But, but, you know, I wanted to go back to what you were talking about, you know, you were talking about, you know, the the guys from LA were, you know, taking too long, you know, I'm sure, you know, you know they were, they were probably, it was probably it was probably a money thing, right? Like they're probably trying to find fund, financing,

Clarke Scott 13:28

Yes and no, they wanted to make changes in the so I'm sure they were, but they're also making changes to the script that I felt were more than unjustified, and I didn't want to go down the road of and I thought about it. I thought about moving to LA. I didn't think about it for very long, to be honest. But the changes were they just didn't suit my Australian esthetic. Not to say that the LA esthetic is less sophisticated, but I just I wanted to produce something that I was going to be proud of as a body of work over time. And in the end, I could see that I could very easily continue along this path, and I could move to LA and I could potentially get something happening, but how's it going? What kind of taste is that going to leave in my lot in my mouth over the longer term? So I made the decision just not to go that route and to stay in Australia, and even if that meant that I was going to end up producing much smaller films. I'd rather do that and earn money in a way that allows me to produce something that had that that I'm essentially proud of the quality because. Dollars of the budget will be less. That's just, that's just true. And I know that's true because I've gone through 1000 moments later we did essentially on my own coin. The actors worked on the back end. So we were all was very DIY. And while we worked our asses off, we didn't, we didn't have, we didn't have the crew to allow us to produce something that was, you know, what's, what's the, what's the cliche that the the the parts and the the parts are greater than the some of the parts are greater than the whole, or something like that. I'm vaguing right now, but yeah, so that's, that's what I decided. I decided that I would pull back and just stay where I am, be a little bit more patient, because I think I was, I think it was sometimes we can, we can push really hard because we feel like it's got to happen tomorrow. And if you look at some of, certainly, some of my filmmaking heroes, they don't look at it that way, someone like Terry Malek, you know, he goes off and he produces his first couple of feature films and then hides for 20 years. What was I mean, no one really knows, other than his close friends and family, no one really knows what he was doing. And then he comes out and does a thin red line. I mean, that's and it's probably the greatest war movie ever made. So, yeah, I wanted to take a different approach. And one of the guys, the Turkish director, by the name of Yuri Baja Long, who did he won the the Palme d'Or in 2014 with winter sleep. I started researching his his career and the way he went about things. So he'd gone in his last film one the palm door doesn't mean a lot of financial return or but it does mean a lot of I mean, it's the palm door. But where he started, he started from very, very humble beginnings. And he started late, like I did so late 30s, the the ice, I could really, I felt close to him, so I was confident in what I was doing, in not going to LA so, but I think the guys in LA that was surprised, to be honest, I think they were,

Dave Bullis 17:38

You know, That's actually an interesting strategy Clarke, because that's something that you know other people to have used, other guests that I've had on the podcast, and that is, you know, in your hometown, wherever that might be in the world, you have advantages and disadvantages. Yes, you know it's not la unless, of course, you know you're in LA, but unless you're born near La. I mean, you know, but, but with the advantages I always talk about it are, you know, if you live in a small town, and you know, a small town America, in the middle of America, and you know, you have a list of people that you know, and because this, the town is smaller, you usually know a lot More people, and usually are able to get things, most likely, for free or even at a highly discounted rate, because they're going to say, hey, look, there's, you know, I'm sure people in Melbourne, you know, and I want to ask you about this, we're probably saying, hey, look, there's Clark, you know, you know, maybe you know in your neighborhood, or you know, the people knew you and said, Hey, look, there's, there's Clark, You know, he's making a film. He needs a car of some kind. He needs this. He needs a location. They might have been more willing to help you out, because, you know, you're a familiar person, and that's why you know, whenever we, you know, when I talk with guests about moving to LA, we always talk about a strategy to it, where they always they either have meetings or a connection, a place to stay, a job already, you know. And it's sort of like stacking the deck in your favor as much as possible, because we both know Clark things will go wrong pretty quickly, as they usually do in this world, but, but you know what? So that you know that is something I've seen before. That's a strategy, but I'm using myself, because even filming here in Philadelphia, it's, you know, the seventh or eighth most populous city in America. And even filming around here, I've been able to to sort of finagle things free or cheaper, because I'm a local guy making a local film, if you know what. I mean, yeah, yeah.

Clarke Scott 19:35

I think it comes down to this. Those that want to move to LA are probably looking to to work in the film industry, but if you want to make films, there's absolutely no reason. In fact, it can be detrimental to move to LA if you want to be if you want to make films, stay where you are. Good stories leverage the tools that we have available to us now to to create those films. And then go out, find an audience, create an audience, if you have to find an audience. And then over time, take the long game. Over time, you'll find that you'll create work if you're talented, because all of this is predicated on talent. If there's no talent, there's no career. Over the over the long game, a talented person will naturally rise. It'll just happen. But if you think that. And it was a guy, a guy by the name of Stuart McDonnell, who's a fairly big director here in Australia. He's done TV. He's done film. He's actually been to LA, shot some some TV in LA, come back to Australia. I knew him through through philosophy, and my interest in philosophy has, he has a similar interest. And he he said to me, unbeknownst of where I was, so I was just some guy that that, you know, he was speaking to, although I knew him through philosophy, he said, Clark, don't line up at the end of the film school. The film school line. I was a whole bunch of people that go to film to film school, he was one of them, or want to work in the film industry, and that line is really long. Do not do that. Go and buy a Canon 5d and make your own film. That's the way to get to get in. And I think that's true even if you do want to work in so I think LA is probably harder, but if I wanted to work in TV in Australia, in Melbourne, which I'd love to do, by the way, the best way for me to do that these days is actually to go and produce something of a certain kind of quality under a certain amount of time and budget constraints, and then show that to the gatekeepers in TV via relationships that I've created through the process of creative, of creating, of making a film, and then over time, and do that a couple of times, and people will see that they that you've you've got the you've got, you've got both the balls to go and do something, the audacity to do Something like this, but you've also got the skills, so not only the esthetic skills, but also the management and communication skills and and also the skills of persuasion. Because you need to be able to go to an actor and say, Look, I don't have any money to give you upfront, but I can give you a piece of the pie on the back end. That's just an example, and that's what I did with my two two actors. But they didn't do it because, just because, you know, just because of that, just because of who I am, they read the script and said they read the script, and it was a fairly undeveloped script as well because of the way I shot it, but we had meetings, and they were convinced that I was the kind of person who could finish a project, and that it would be of a certain kind of quality. So they came on board for those reasons. So I was able to I was able to get great actors for my project through my ability to communicate with others. If I take that as a package to a TV producer, someone who actually has money to produce episodes of television, here in Australia, there's a good chance that all of that information will go down a lot better than some kid that's gone through film school who is, you know, who's got a great looking CV, but, but nothing other than that. And I know that that's true because there was a an Australian directors conference a couple of years ago, and they recorded all of the sessions. And I was listening to it. It may have been three or four years ago now, and one of the sessions they had was breaking into TV, and it was a whole bunch of both TV execs here in Australia and producers. And the one thing that they all agreed upon was that that the the road, the path to becoming a director in episodic programming here in Australia was not necessarily your esthetic style, but your ability to get the day done to shoot. If you got to shoot four pages or six, or, excuse me, Dave, six pages, then you've got that, that kind of general esque ability to get a whole bunch of people together and move them along through the day and to make the day, and that's the one skill they all require, because then they're going to hand over half a million dollars or a million. Dollars for a production to someone who who can't make that happen. So that's the skill they're actually looking for, and that, if you think about it, that makes total sense. If you have a director who doesn't have those skills, you don't have a television program, you don't have a product to sell. So from a producer's point of view, that almost Trumps esthetics. So yeah, that was a bit of a rant. Sorry Dave.

Dave Bullis 25:32

No, no, no problem. You know, people on this podcast tend to rant. Clark, so please, you're, it's, it's par for the course. I tend to bring that out in people, but, but, um, but, but, but, no, I agree with you completely. You know, I used to be a part of a screenwriting group, and everybody who was, who was in it, was a lot further ahead. I mean, this was years ago, but they were further ahead than I was. And I remember the one guy had just got done pitching to the Sci Fi Channel, and he had, he said two things that he took that, that I really took away from what he said. He said, number one, you know, when you're in those pitch meetings, they don't care about what your dreams are. They only care if what you're pitching to them will be profitable and viable in that market. Number two, when you go into a Walmart or a wall, or, yeah, Walmart or a Best Buy, or, you know, anywhere, you know, you have that physical shelf shell, shelf space, that is, you know, everything has $1 amount to it. So he said, when they put out, you know, those movies, you know, like, you know, zombie headhunter, 18, the reason that they give that shelf space is because that's going to sell a certain amount of units, and they know exactly how many, usually, they can make a, you know, prediction, or, you know, an estimate of how many units that's going to sell. And they're able to, you know, calculate that up and then give that X amount of shelf space. And you know, I started to take that and realize, you know, this is so true. That's why you see movies, certain movies, and you don't see other movies. It's because, you know, they wanted to make sure that they have a viable product. And you know what you were just saying, you know, obviously, yes, you know they're not, you know, it's like what Dolph Simons always says. You know, they're not just gonna give somebody fresh out of film school $100 million and say, Here, go make this movie, and then, you know, it's gonna be in every theater in the world, and you're gonna make, you know, $10 billion it just doesn't happen that way. You know, you have to make a movie, you know, even, even if it's guerrilla filmmaking, even if it's no budget filmmaking, where it's, you know, you know, you yourself. And maybe you get some, you know, hire some actors, you get a move. You go gig, you get that. And if, and if it's good enough, if it's slick enough, they'll give you, then you can tell producers, look what I did for nothing. Imagine what I could do for 10,000 and then you sort of move up to 50, then 100 and then as you can keep increasing that process with more money, then they'll start, you know, trusting you with the bigger budgets and the bigger crews and all that stuff. And then, you know, finally you can, you know, start, start getting that, those big paydays, but, but, but, you know, I agree with you completely, Clark, and that, you know, that's, that's where I'm at right now too, is trying to convince, well, I'm trying to actually write stuff right now, but then that the part will be to convince, you know, hey, you know, give me money. I'm not a, not a complete idiot. I'm a somewhat of an idiot. Clarke, but I'm not a complete idiot.

Clarke Scott 28:09

Yeah, I think, I think we need to, I think we need, we need to understand the game that's played and to not belittle the game. So sometimes I hear, and I'm not suggesting this is what you're doing, Dave, but I do hear younger people, it tends to be complaining about the state of the industry. And I think if you're complaining about the state of the industry, then you're actually two things. You're missing a massive opportunity that has afforded us as filmmakers these days, regardless of your age and the tools that are available, but you're also you're kind of missing the point of how, how the game is played. And that's not to say that this is a business. You hear the opposite is. You hear people say, Well, it's a film business. When I hear that, I think, yeah, you're a marketing bullshit artist. I don't know if that translates well to the American kind of vernacular, but you're, you know, someone that that's all marketing, all it's all source and no substance. The guy the game that, and even use the phrase the game, I'll change that up. The context in which we live is such that our industry is and works on the supposition that it is product based, and the only way that we can get stuff made is to is to give someone something in return that helps them feed their family. It's called money. It doesn't have to be a dirty thing, so we can either. Yeah, and I don't believe that you have to live on either extreme. Either we you're one of these people that say it's the film business, or you're one of these people that is pure art and and hates anyone that's wearing a suit. I think there's a middle, a middle way approach, to use a philosophical term, from from India. And the Middle Way is understand the context in which you live, and then live as best as possible. So within the context of filmmaking, understand that that it requires money, and it requires it requires money in a way that without it, it cannot work. And there and then pitch yourself with at the at the the level at which you want to make your art. So for me, going to LA wasn't going to work, because I would have to, I would have to produce and create stories that didn't have the kind of esthetic appeal that I wanted to be able to show other people and say I did this. So therefore I have to bring and even the notion of levels that somehow that that's a better level than you know, the LA films are better because they're more money, I think is kind of weird, because some of the best films that I've seen are are actually made for a lot less money, and they're a lot more important, and they say a lot more important, they're not, it's not popcorn, but not popcorn movies, but they do, and they will live much longer in cinematic history than a lot of films that come out of LA so I think by understanding the context in which we live and work, then we can better understand ourselves and our own esthetic, and then move forward with confidence, both from a from a producer's point of view, and which is The kind of the sooty side, the business side, and from the the the artistic side, from the director, writer, cinematographer, from from that side, so that you're not butting heads with these two aspects of filmmaking, but you understand each side of the story. And even anyone that that has to write, direct and produce their own material has to balance those aspects out anyway. I know that's what it was like with 1000 Moments later, I had actors saying we should be doing it this way or that way, and they don't know the story. They don't know how I want to shoot it, but they also don't know how much time we have. So there was some scenes that I I got one scene in particular where we did a lot of takes, because the actor was just not getting what I wanted. And it was very, very important to me and to the film that she delivered in a certain kind of way. And she never, never really quite got there. But we ended up, I spent probably two days getting this one scene, and in the end, it was just, it was, she was super frustrated. But that's actually that frustration. There was two things that happened. Dave was the weather change on the second day. So we actually got stormy weather. There was a big storm that was coming in, and she was backing into this storm with this kind of a tirade of dialog at her, at her, at her husband, but because she was so frustrated by the fact that she just wasn't able to get what I was asking her to do. And it wasn't a lack of skill, it was what I was what I was asking you to do was actually really, really fucking hard, because she was frustrated, frustrated with me, frustrated with herself. They came out in the performance, and it actually improved the performance, but the only way we were able to get there was to spend much more time than was originally allocated for that particular scene. But I knew that I could do that because I knew the scenes after that we could get on the same day in a car, and I could just rip through them, because I was also the cinematographer, so I knew, Okay, so if we just go down this road and then turn there, I can point the camera this way. I can do that. I can point the camera that way, while the actors are just we're going from 111 location to the next. So I think by understanding the context in which we live, both from a human point of view, I think that it's true. If you look at your own life, if you understand the context in which you live as a human being, then you're able to be a better human being. And it's only when we live from from through ignorance that ignorance influences us in in negative ways. So again, another, another rant. Apologies,

Dave Bullis 34:56

Like I said. Clarke. No, no worries at all. You know, I wanted to ask about 1000 moments later. So, you know, what was your what was the you know, when you started writing the script? I wanted to ask, you know, I wanted to ask, did you know? Did you subscribe to any sort of method when you write? Or do you, you know? So, how you know? Basically, because, obviously, everything starts with the script. I just want to ask, you know, how you put that all together?

Clarke Scott 35:21

Okay, so here's the thing, by this stage, I was, I'd I was super frustrated. I'd spent a couple of years writing a number of scripts, working with producers, and I got to a point where I just, I was deflated to I was going to say I was ready to give in, but that's not true at all. But I was certainly deflated in my enthusiasm for working with others. And I'd just recently found the Turkish director that I mentioned earlier his work, and I'd researched him, and I'd emailed him, and I was super enthusiastic about how he about his life and how he went about things, and I basically had a little bit of a man crush on this guy. I was certainly a fanboy. I love his esthetic. I love the way he moves the camera, but I also love the way he goes about it, and that is the way he does go about it. I used as a template, and that is to say, I'm not going to rely on anyone, no one. I will do everything. And with from that point, you then go out into the world and you tell people what you're going to do. That enthusiasm and that kind of resolve somehow shields, it makes you bigger than you really are. And people, people want to be a part of that kind of magnetism. So I, I, I essentially, I think, at the roughly at the same time I came across the movie Blue Valentine by Derek C in France, with Michelle Williams and Ryan. Ryan Gosling, who's the male actor? Yeah, Ryan Gosling, great film. If you haven't seen it's a beautiful little film. But look at the, look at the behind the scenes and going to how they got, how they had, how they shot it. And I wanted to use that kind of semi doco style, because I knew that I could, I could produce a film in as in a similar way. So what I did was, I, I, I used, I actually used Aristotle's cathartic moment and structure of his dramatic storytelling as the bedrock from which the story grew. And I also started with a theme. And the theme is that love is a choice. So love is not something that happens to us. It's, in fact, something that we choose. And I then wrote an outline that that essentially resolved that issue. And the way I did it was I went, Okay, so I need two actors, like Blue Valentine. Let's put it in like a mate, make it a road movie. So I can, I can get, I can use, we've got a in Melbourne, we've got or Victoria, we've got a road called The Great Ocean Road. And it's this, this road that winds around a coast that is incredibly scenic. So by putting two people in a car, making part of it a road movie, I can use the natural environment as part of the set. So I'm getting production value from, from where I've shot the film. That was something that that new Bella shallon had used. So I'm not really, I'm basically just copying others in a lot of ways. What do they say we we, we stand on the giants of we stand on the shoulders of the giants that have come before us. And I did just that. So I took aspects of different filmmakers the way they got things done, and then just uses those as both inspiration and templates from which I would then work. And so I had this outline, I then put a casting call out and and made it sound, I mean, I told the truth, but it, but it sounded like a fantastic little story to be a part of, but I didn't make it sound better than it was. I just, I'm just, I spend a lot of time nuancing The words so that I would get the right kind of people. And I think I auditioned about 80 people all up. In the end, actually was 160 was 82, men and 81 women and but even that, the audition process is pretty simple, because as soon as particularly with Lily, as soon as she walked in, I knew this was the girl. And the reason why I knew this was the girl was that she had food poisoning, yet she still turned up. She walked in and apologized. She looked like shit. She was really crook. She had sweat pouring down her face. And halfway through the interview, which didn't go for very long, because I felt sorry for her, she's she excused herself and ran off to the toilet, but I knew it was her immediately, because anyone that wants to be a part of a production that much, then they're going to see it through. And of course, I had to, I had to make sure that she could act. She looked the part. She looked great, right height, right eye color, right hair, all of that stuff. But she could also act really, really well. So, but she, she won me over by just turning up crook. So she had she had gusto, which I loved. But to be honest, even when we were into pre production, when I hired the actors, they were on board, I hadn't finished the script yet. I was still writing the script, actually, as we were right, as we were shooting the film, there's a there's a few big dialog scenes that I wrote in the days before that were they're not just dialog with two people talking. They're they're actually a part of they function in a way that tell the subtext of the story. And I did it that way because two things, I knew I could do it. I knew the story well enough I did. I'd had visualized basically every scene, every look, every turn that the the actors were going to do before I'd even written the script, so I knew the outline. And this is something that I heard Derek see in France. This is what he does. He He visualizes the film ever like every cut, every shot, every cut, and he's got a detailed visual outline in his mind before he's and he's writing at the same time, so the outline kind of gets fleshed out, if you like, over time, through this process and and I'm a very visual person, and I find myself writing in a similar kind of way. And I've heard other writers right in similar ways. When it's in, when they write prose, they write books, but they'll write via an outline. So so we did that. And what that meant was that that I I knew the film inside out, and then it was just a matter of finding interesting ways and interesting locations to embed that story in. And we did that. We we Chris and I, the actor who helped me a little bit with, with with the producing side. We'd done a scouting location. So I, I had this one scene where, after a little bit of a battle, they they come along, and then she's, it's, it's a, it's a moment in the film that's supposed to be slightly comedic, but its function is to just release a little bit of tension. So storytelling and movies are kind of like jazz, right? It's tension and release it slope music. So there's this really tense part, and then there's this kind of letting go of that, and then a slight comedic moment before there's another piece of tension. And in this I needed to find a certain kind of location, so we went for a drive down the greater road, and we just drove around for a day, and I made notes, took a couple of photos, and then when we were shooting, we just drove to where we thought that would work. And if the weather was good, great. If the weather sucked, fine, no problems. I'll shoot in a different angle and then try and cut it all together. So that seemed to work really, really well.

Dave Bullis 44:20

So, you know, that's excellent, you know what? You know, you find the process that actually is going to work for you. You find a process that, you know is indicative to the project. And, I mean, I think that's, you know, a key that a lot of filmmakers miss, is that they they try to emulate too many people that that may have either more time, more money, more people, whatever. But if they could just, you know, find that process, you know, that that can, that fits in, within their budget, and fits within his, in his, you know, fits with the project, they would have more success. I mean, I've done that myself as well, where I've, you know, tried to emulate too much and try to do too much with with with not having. Having the proper sort of foundation set, if you know what I mean,

Clarke Scott 45:03

Totally if you you gotta watch a bunch of film school kids or young kids try and produce, try and create a feature film that's sci fi, it will probably suck, because they just don't have the millions of dollars that it takes to make the special effects not look laughable. I've never seen one sci fi, and I love sci fi, but I'm not a sci fi geek. So there's probably people out there going, what an idiot. That's just wrong. But from my, my point of view, it never works. And but what does work? If there's, there's actually a really good behind the scenes of the film brick. I'm vaguing I know the guy first. The guy's name is Ryan. I can't remember his surname. He's now directing Star Wars and but he's Ryan Johnson. Ryan Johnson, that's him. Great guy. Really, you should try and get him on on your podcast, or maybe because he's doing Star Wars now he's too busy, but he's incredibly approachable on social media. He's done some great films, but his first film brick, there's a there's a fantastic behind the scenes on that, and you'll see that he's done the same thing. Use the sets. Use the locations you know from your local area that will add value, production value to your and that you can get for free, right? Because you can do you can use if he used a car park from his school. He used his school, his high school, in fact, because he knew that area. And the film, the film is great, and it has a, it has a kind of a film, you are kind of vibe to it. I think the first time I saw actually, was on television, late night television here in Australia. And from there, I then researched and found this dude, and it's amazing some Yeah, so that's both. He's just he, I'm I've done exactly what he did. He's probably got more talent and skill than than i i have certainly had more money, because bricks still the bricks still cost money, but it was done in in in a time prior to DSLR. So I think if he was around today, he wouldn't, he wouldn't be making excuses. He'd be, he'd be the kind of guy that just go out and and use the tools to his advantage, so rather than so DSLR can be or, you know, the new Sony's is quite I shot 1000 moments later on an A 7s use the esthetic of the of the equipment you've got to enhance the story, not try and create a million dollar looking film on something that's never, ever gonna look that good. It's just not so, yeah,

Dave Bullis 47:56

you know, you brought up the film students trying to a sci fi piece. There was some film students that I knew who were trying to do a time period piece, and they were trying to raise 5000 on Kickstarter. And they, they asked me what I thought of it, and I said, Guys, you will spend $5,000 on costumes alone and and that will only for half of the of the cast. I got one costume. Yeah, yeah. I mean, the because you're doing something from the 1800s where everything was a lot heavier, it's, you know, all of this stuff that, and just to get, and I've dealt with those rental houses before who rent those kind of costumes. And, I mean, it's not like because I think they're thinking that they could just skirt by by getting some, like, cheap replicas, you know. But I told them, You people are going to be able to tell that, you know, people are going to be able to tell this stuff. And if it looks chintzy and cheap, you know, if the esthetic looks chinchy and cheap, the production value looks chinchy and cheap, it's going to come it's going to come through. And I said, you know, you could create a better movie setting it in today's world, and just, you know, using what you have access to and creating something that way. And then you can move on to do something else. You know, when you need we have a more audience, more of a budget, you know, stuff like that. Just tweak the story like you could do. You could make them speak like, use, use the costumes of today, get them to use their own clothes, but make them speak as if they're from the eight and hundreds, and tweak the story so in an interesting way to leverage what you've got on you right now, that's, that's, to me, I'd be more interested imagine a film, of course, the story's got to be good about a bunch of people from the 1800s but, but, you know, somehow their their clothing is all modern. I mean, to me, that's far more interesting already. The only people that can do period are people who have the budget. Downton Abbey is Downton Abbey, and it's never, ever going to be shot without millions and millions of dollars behind it, because it just would not work.

Dave Bullis 50:11

Well, and we were talking about brick, you know, brick was set in modern times, but everyone talked like they were from like, the 1930s or 40s. You know, there was like, a, you know, they kind of, kind of speech. So, you know, I wanted to ask you 1000 Moments later, you know, it's, it's in post production right now, correct? Clark, that's correct. Yeah. So do you have a time? Do you know of that you have an estimated time to be when will be released?

Clarke Scott 50:35

I'm hoping to release it or submit it to a couple of film festivals, and then I'm going to self, I'm not going to sell it, even if someone was willing to buy it. I'm going to release it on iTunes and basically do a digital release after a series of a film festival run. So that, you know, with film festivals, that's a little bit of you're basically just leveraging, leveraging them for marketing. So again, looking at the the long term game here my my thought behind this strategy is, is this, if I can get the film into a film festival with a little bit of prestige, I can then use that on my CV, and it's really that's the only thing, the only reason why I would do this if it can get into a Sundance, and the likelihood of getting into a Sundance is just ridiculously slim. It's ridiculous to even mention the name Sundance, but I'll do it just for an example. If 1000 Moments later, was able to get into Sundance, I could then go to a producer and say, here's here's a screener for the film. We are in Sundance. Here's my name, here's my CV. Please give me and here's another project. Here's another script. This is the thing I want to do next. Can you help me? Someone is likely more likely to to help at that point then if it's not in Sundance. So we can, you know, Sundance, slam dance, there's, there's a bunch of film festivals that I can use to help me step up on my next with my next project, and then, and after that, then I will release it via iTunes, the digital platforms, and try and recruit recoup the money that I spent, which wasn't a lot, we're talking, you know, 1000s of dollars, not 10s of 1000s of dollars, certainly not hundreds. That's probably including my time. It'd be 10s of 1000s, but not hundreds of 1000s. I'd like to be able to recoup that money and and then pay the actors for their time. So that's what I'm looking to do.

Dave Bullis 52:54

Yeah, you know, I guess they had on here. Jason Brubaker always would talk about that as well. He'd always say that, you know, getting into Sundance is not a financial or distribution plan, because a lot of filmmakers would say that, you know, that would be their pitch to investors, or even to anybody else would be, hey, you know, we're going to get this into Sundance. We're going to sell it for a mill, and then that's how we'll recoup the budget. And he said that's not realistic, because, you know, every year, Sundance has more entries than it had the year before. And, you know, they have all sorts of movies coming in, and it's just, you know, it's a, it's that golden ticket type of thinking that he always tells people not to do. And instead, just get a website, put a big Buy Now button on the website, and you could sell your film through your own website,

Clarke Scott 53:39

Sure. And it not only is it, I mean, it just that's not how Sundance works anymore, and it hasn't for quite a while. So anyone that's saying that to investors is cheating their investors, because that's not how the business works anymore. The business has fundamentally changed over the last five years, and even over the last two years. You just look at digital platforms that are available now compared to two years ago, we are, we are in a totally different environment. So anyone, anyone that wants to lay down some coin on the on the potential hope that you even get into Sundance, let alone someone gives you a million dollars. No, it does not happen that way. And you've just you, anyone that understands the way distribution, even traditional distribution, works, will will know that the possibility of recouping money is is so slim. I'm sure, look, I'm sure I'm probably overstating the facts. I'm sure someone will say, Clarke, you're wrong. Here's an example, sure. Okay, but how many films applied at Sundance, let alone submitted? Or what's what are the numbers that 3000 feature films

Dave Bullis 54:56

Last year, they had 15,000 submitted. Yeah.

Clarke Scott 55:00

Yeah, so, so, yeah.

Dave Bullis 55:04

And you know, every it gets more. Every year, you know, Clark, we've been talking for about, you know, 50 minutes now, you know, just in closing, is there anything that you know we didn't discuss, that you want to just talk about, or is there anything you want to sort of say to put a period at the end of this whole conversation?

Clarke Scott 55:22

Um, not really. I think we've, we've, we've gone into we're gone, we've, we've dived deep, haven't we?

Dave Bullis 55:31

Dave, yeah, well, we have dove pretty deeply, yep.

Clarke Scott 55:35

So yeah, no, no, I'm, I'm cool, man,

Dave Bullis 55:39

All right. Excellent. Clark, where people find you out online.

Clarke Scott 55:42

Best place is Clarke Scott. That's Clark with an E clarkescott.org from there almost social media links. There's a newsletter. The links to 1000 Moments later, website where people can there's a newsletter there, also with the film. Once I do release it, I've got a load of of behind the scenes, things that I've produced for and bonus content that I produce for the film. So you can, you can hire and here in lies the real benefit of of the the age in which we live, I can on my own bat, in a day, whack up a website, throw up a website and a buy button or a hire button, and as long as I've produced content for it, I can give people an option to just hire The movie for 48 hours, or buy it for download. They can buy that and behind the scenes or and I've got three packages. The full package I go into it's basically a, almost essentially a course in how to produce your own independent film. And I do that for like 50 bucks. So for 50 bucks, I'm opening the door to my entire process, from the screenwriting how I used Aristotle's cathartic moment and his structure to create the dramatic and thematic essence of the film, through to screencasts of how I edit interviews with the actors I've got. I recorded the voiceover session with with Chris, so you get to hear him stumble through the voiceover and me give him points and notes, directors notes on you know, we need to do this and that, and it's totally unedited. There's no in that. At least there's, there's, there's no, no editing so, and I can do that for virtually no real upfront cost, because I've got all the skills and all the equipment and all the all the tools at my disposal in order to create all of that, and then I can just put it online. And the way I look at it is that if, if people, if they, if people want to buy it, then it's there. If they don't, no problem. And that will help. It helps both me, but it's also it allows me to give something back, if I, if I use the word universe, it sounds kind of new agey, but I'm just, I'm giving something back to whatever it is that allowed, that allowed me to be born and be sitting here right now talking to you and that with that from that place of generosity. I'm hoping that over time, people will just, I mean, there will be some people listening to this now, in fact, if they've got this far, they're probably thinking, there won't be too many people who think that I'm an absolute wanker, but there will be people who go, I don't like the way this guy talks. I don't like his his esthetic, but there are, and they're not my people. They're my people. Are the ones that look at my work, that look at my esthetic, that look at the approach that I've taken, that I've taken, and they go, this guy is fantastic, just the way I looked at Nuri Bala Jalan and went, Man, I fucking love this guy. He, he's so ballsy. He, you know, the first film he did, he used his own money, and he did everything himself. And I love that approach. I got really excited and inspired me. So by me putting this stuff out out there, I'm helping others. I'm being generous, because it's a hell of a lot of work for 50 bucks, I'm not going to make any money back, but what I will do is create connections, and I believe that those connections, fundamentally are is the foundation of a good life. You cannot have a good life without other people involved. Involved, family, friends, etc. So, yeah, sorry, Dave, I ended on a rant, right?

Dave Bullis 1:00:07

It's no problem at all.

Clarke Scott 1:00:09

I will. I think you're right. Yeah, you bring it out, right? You really do. It's like, I do. I'm sorry.

Dave Bullis 1:00:15

I mean to cut you off, yeah, you're right. And I go for it, yeah? I was just gonna say, I do. I just have a tendency to bring that out in people. Clark Scott, I want to say thank you very much for coming on the podcast.

Clarke Scott 1:00:25

My pleasure Dave great to speak to you.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

LINKS

- Clarke Scott – Official Site

- Clarke Scott – IMDb

SPONSORS

- Bulletproof Script Coverage – Get Your Screenplay Read by Hollywood Professionals

- Audible – Get a Free Filmmaking or Screenwriting Audiobook