Right-click here to download the MP3

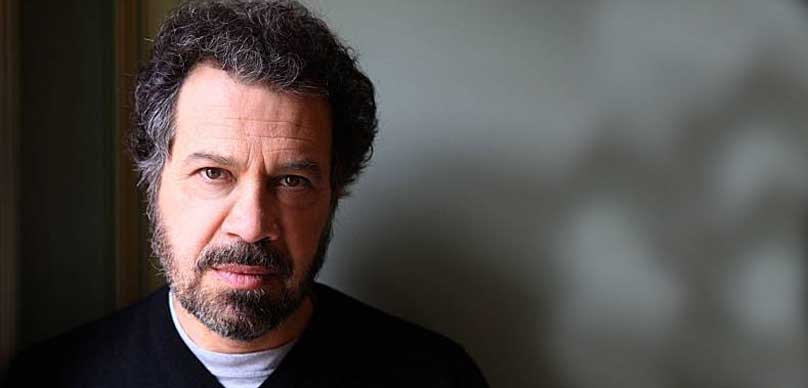

There are a few filmmaking books that have made as big of an impact on the craft of directing like today’s guest’s Film Directing: Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen, written by director Steve Katz.

Shot by Shot is the world’s go-to directing book, now newly updated for a special 25th Anniversary edition! The first edition sold over 250,000 copies, making it one of the bestselling books on film directing of all time. Aspiring directors, cinematographers, editors, and producers, many of whom are now working professionals, learned the craft of visual storytelling from Shot by Shot, the most complete source for preplanning the look of a movie.

The book contains over 800 photos and illustrations and is by far the most comprehensive look at shot design in print, containing storyboards from movies such as Citizen Kane, Blade Runner, Dead-pool, and Moonrise Kingdom. Also introduced is the concept of A, I, and L patterns as a way to simplify the hundreds of staging choices facing a director in every scene.

Shot by Shot uniquely blends story analysis with compositional strategies, citing examples then il-lustrated with the storyboards used for the actual films. Throughout the book, various visual approaches to short scenes are shown, exposing the directing processes of our most celebrated auteurs ― including a meticulous, lavishly illustrated analysis of Steven Spielberg’s scene design for Empire of the Sun.

Enjoy my conversation with Steve Katz.

Alex Ferrari 2:04

Today's guest is legendary author Steven Katz, whose book film directing shot by shot visualizing from concept to screen is been one of the best selling books on directing ever it is a book that had a huge impact on me. And the book is celebrating its 25th anniversary and it's sold hundreds of 1000s of copies over those years. And I wanted to have Steven on so I can pick his brain on what he has learned over the course of his career and all the massive amount of research he put into this legendary book. I mean, he has like over 800 photos, illustrations, and is by far the most comprehensive look at SHOT design ever put to print. So without any further ado, please enjoy my conversation with Steven Katz. I like to welcome to the show Steve Katz man. Thank you so, so much for being on the show. I appreciate it.

Steve Katz 3:03

Thanks for having me.

Alex Ferrari 3:04

Yeah, you know, uh, guys, so if you guys don't know, Steve's work, he wrote a book a seminal book for filmmakers called shot by shot back in 1991. And that book was one of the one of the first books I ever read on the craft of directing. And it was around the time I was getting into college. And it changed my life it really did was a wonderful book. And it's something that I refer to for years to come. It's just it's just one of those seminal, you know, filmmaking books. So I'm super excited to have you on the show, Steve.

Steve Katz 3:36

Well, thanks so much. Glad people like the book. It's been out there a long time. Then we just did the second edition. So long overdue.

Alex Ferrari 3:43

Yes. Yes, yes. Now, how did you get into the business in the first place?

Steve Katz 3:47

I was a kid filmmaker. And I grew up in Westport, Connecticut, which is a very it's in it's in Connecticut, and quite near New York is considered a bedroom community like in Mad Men. Okay, though, and so we have live advertising people but it's known as sort of a Hollywood illustrators art and we had the famous artists was their famous photographer, famous writers, Rod Serling was there live there. And f Scott Fitzgerald and Harpo Marx and Betty Davis and Johnny Carson and the Newman's Of course Paul and Joanne and many, many, many others, and it had it had the oldest summer stock in the Westport country Playhouse which was a feeder to New York. So there's a lot of this stuff in town, relatively small town 28,000 people. And my mom was a illustrator in early part of her life and then she became a businesswoman. And my dad was very seriously into photography up until I was like five. But you know, there was an appreciation for that and then in our living room, we had a tons of shelves and filled with books and on the bottom shelf for all the coffee table size books. So from the time I was a little kid I remember flipping through you know, they were coffee books about artists and photography with Brett West End and minor wide and ancel Adams On photography and on the art side was just you know, Janssens history of art and all that. So I was always doing that. And then when I was, my dad had a camera with a revere, eight millimeter with a stop motion button. And, and like most kids, I was into Harryhausen in horror films and all that. But I also like to read so there was a story in Paris as well. But anyway, for one year, my life, my dad's company, flew him out to Cal, cool napkin on the same scope in the middle part here. And then one day, when I was nine or eight, I went to a, to the pharmacy kind of magazine store with the old counter with the stools and ate ice cream and all that anyway, make a long story short, I find a magazine called Famous Monsters of filmland, which is everybody knows that of a certain age. And I'm flipping through it and and it was the first time I was now I love movies at this point. And my mom and dad, well, particularly my mom loved movies, and we would sit there and watch old movies rather than TV shows. This is in the 50s. And then, so I knew a lot about movies, because I'd be sitting there with my mom, and she knew all the secondary character actors like and whether it was in, you know, Adventures of Robin Hood, or whatever it happened to be. So I was absorbing all this. And then, so I looked at this magazine in a drugstore and I'm like, wow, here's this armature for willalso Brian's King Kong model, and, and, you know, Marcel Delgado and all his work, and then the illustrators from our kayo, who were fantastic. So then may make long story short, I saw storyboards. So I was like, Oh, my God, this looks, I draw, I like photography, I was encouraged in my photography. So it all kind of came to a head, it was almost moment, right? In that moment, I said, Wow, I'm gonna, I'm gonna do with this, I'm going to do this animation thing. So I got into that for a while. And that was my start. And then I just started to get books on film. And when I was in high school, we had probably, I think, the best theatre company in the United States in staples High School, and was running like a professional theater. And we would end the same people there. I would go in the summers. And I would sit in the dark and the Westport country Playhouse because I was working there. And I would watch famous directors direct for, you know, usually for two or three days before the show star would go for a week, it was Woody Allen, and it was Josh Logan, and many, many, many others. And that was when I was probably 1415. around then. And, and by that time, I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker, and I'd gone from the eight millimeter to a bolex. And I also the other thing that sort of, I guess pushed me in that direction was that I had a second cousin, my dad's first cousin, Milton Olson, and he was the senior visual effects projectionist in New York City and he owned all the process gear so that was like a Mitchell. projector and water cooled carbon arc, and then it had a marked Oh, it was a massive carbon art was like I think it was like a, it was like a 14 millimeter carbon maybe. And then, and I was on set then on car 54. Where are you when I was 10 years old? Wow. Four story stages up in 120/6 Street in Manhattan. And then some years after that. I was on a set was Burt Reynolds before he became famous on a TV show called Hawk. And he played an Indian detective in New York. Yes, and different times. Right there and I was there for all the background projection. So Mike Melton would have me go on there. And I learned how to load and all that stuff. Before I was 16 years old. And he also did a lot of stuff with projection with, you know, rear projections with slide projectors and stuff for large corporate presentations. And I got into that as well. And that served me well, because when I was 17, stop me if this is boring.

Alex Ferrari 8:54

I mean, what was basically what basically what you're saying is you were kind, it was kind of destiny, basically.

Steve Katz 8:59

I guess it was, I mean, I made some choices along the way. But I was, you know, it was just around me. It was just available in nearby and people close to me, encouraged me at some level, not all the time. But anyway, so I got into live shows. And I did that for the Grateful Dead and a bunch of those things. Starting when I was 17. Then I played bluegrass banjo for professionally for a few years. And then when I was like 25 or 26, that was ridiculous. I've got to get back to filmmaking. And even along the way when I was 22, I think john McTiernan, who did diehard predator and read October, he married a girl from high school, who is a good friend of mine, and he made a film his first kill demons daughter, and 16 millimeter and shot it in Westport, Connecticut. And he came I was 21 years old. I was I was on the nagre for like, some of the time was the sound guy. Other days I was the productions like because I can I can write and draw, I mean, I can draw and do some sculpting and physical things. And so I helped with that, and so I got to meet john. And so I was

Alex Ferrari 10:02

How was it working with john and his like, first film

Steve Katz 10:05

He was a kid. He was like 20. We're both 21 and 22 with 16 millimeter. It was just at a school. And john, john is, you know, he's a, he's the real deal. He understands film craft, he has an eye, he understand understands sequences go together was very, very good. It was very professional at that age. And that way, it would be a decade before he then broke through.

Alex Ferrari 10:27

Right. And that's a good message to everyone listening, you know, someone like john McTiernan, who is arguably one of the best action directors of all time. And, yeah, he's basically created Die Hard, which is basically the model from I don't know how many rip offs in the course of the decades to come even still, to this day, people are rolling off Die Hard and predator for that matter. Two of the greatest action movies of all time. He he took it took a decade to look for someone to go, this kid has talent.

Steve Katz 10:55

Yeah, no, that's true. And so he went, he got back into Juilliard. And his wife, I think, was production managing at the Met. Maybe I may have that wrong. So check that fact. But anyway, john did go to Juilliard. Then he came out and did corporate move down to the west coast. And he was doing corporate films and just shooting shooting kinda like I did. And some world and I don't even know where the connection came into haul into a into theatrical. But he everything he was doing was pointing him in that direction. And that's what he wanted to do. He just was making the living, shooting anything he could. And somebody was early 30s. He was already I think he did. I can't remember. And nomads. Yeah, no, not the script. And I can remember my sister was investor on knotfest. She was at Viacom in New York City. And she knew that I knew john. And so she said, Hey, you know what I got? internally, I got some coverage on your friend John's, a film Nomad. And you know, and so it basically what it said was a glowing report about john, they said the script was pretty good. But they said, this guy's a real director, we got it. And that was I think, that was that got him into the business. Now, always in the business to do Nomad, I should say that,you know what I mean,

Alex Ferrari 12:06

But got him to get them to the next level. Now, I want to ask you, you since you've written shot by shot and you've discussed the craft so much in your career, what are some of the biggest mistakes you see first time filmmakers make?

Steve Katz 12:20

Wow, well, you know, I'm biased because, of course, I like to pre plan a lot, and improvisation is great. But I see many directors who come in and they have not planned out their shots and they wait to do it on the day they're doing it. They may have a shot list they've done, but they haven't really considering where the tools are today, they haven't done everything they can to eliminate waste of time, which is what it really gets down, you got an eight to 10 hour day. And that's the that's your that's the thing that, you know, is certainly one of the major controls, or limits to what you're going to be able to do artistically. And everything takes longer than you think. Oh, and he's always, yeah, so you just you just doesn't we know you in your head, you know, if you're new director, you go home, we're gonna do this and this, and then it goes off the rails pretty quickly when you get on set, you know, most of the time because you're dealing with actors, and they have their own pace. And you know, and I remember once I wrote about the fact that someone was talking to you about directing to two actors who work at very different ways. One who got things in the first two or three takes and didn't like to do it over and over and another actor in the scene who had to work with, and actually it was Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor, Richard Pryor didn't like to do things over and over. And, and whereas Gene Wilder like to kind of build up. And so those are kind of things to get on set. So I'm just a little odd practice. First timer mistakes, I would say not planning your shots out with even thumbnail again. And I think doing, I've seen people come in with that, not knowing how to do a rehearsal, a blocking rehearsal. So I think that's

Alex Ferrari 13:56

Can you explain what a blocking rehearsal is for people

Steve Katz 13:59

Right, right. So you're going to, you're going to, you know, shoot your scene. And, you know, you're ambitious enough that you want to have multiple, you know, you're going to have establishing shots, you may move your characters around the room a little bit. You'll have shot rivers show you some things that are going to look like covered, but some things that are not. So you have to figure that all out. So you go into the location, and with your actors, and you basically start to do the scene, but it's a rehearsal, there's no shooting, and at that point, and you might take an hour might take 45 minutes in the morning, to go. So it was time to sell the blog where you guys are sitting here with the DP. And you know, now if you're starting with really no idea and you're and you're more of an actor's director, you should have had some conversations with your dp and looked at some movies and things. But let's say you're pretty raw on that first day or third day, whatever it is. And you're going to basically, you know, walk through the scene with the actors and then say, well, could you go here and they're going to say whether, well, I don't feel comfortable, why would I go there? Well, Let's find a reason. And then you work it out with the diet through the dialogue with the intention, whatever that actor is supposed to be doing in the scene. And you you're asking them to do things, sometimes that is extra work for them. But and by that I'm talking now about an actor say, they don't like to hit their marks, having to move around the setting a complex choreography is a distraction to the actor. So those are things you have to learn to do. But that's what a blocking rehearsal is, you don't know where they're gonna stay on set, when they're going to get up when they're going to sit down while they're sitting at a table. For the whole time, that's easy, but what happens when they're not and you want to use the room more. So that would be then then that also includes walking through that with the with the DPS, the DP is saying, okay, we can do that, and I can move the camera. Well, how much extra time is it going to take? Well, we got to move the furniture here and relight this a little bit. And and so you got them in the in the line producer and your production manager and you're an A and your ad and you're conferring on whether or not it's such a great idea to do the dolly shot, or the boom shot and how much you willing to give up. If you do that. You may lose this at the end of the day. So those are the kinds of decisions that are being made during a blocking rehearsal. But if you storyboard nude first, you eliminate a lot of that.

Alex Ferrari 16:17

But isn't it? Isn't it true that directing is basically compromising? That is the biggest thing that directing is you're compromising constantly because of things and elements that are being thrown at you on a daily on a minute by minute basis on set?

Steve Katz 16:29

Absolutely, then that is exactly what it is. It's all everything is a negotiation between the actors, and your ambition artistically in a good sense. And then all the other people who were there kind of to make sure you you know, everybody stays on track, which is the line producer down in the DP. And much of the time lighting is is the time consuming part. Even you know, and so that's how fast is your crew? And what are you willing to do now, with the new tools, you can go back after the fact and do some cleanup in lighting that you otherwise couldn't have done. But then you know, that's extra expense. And you can't do everything that way. But we're moving in a direction where you can but I mean, you're gonna be able to extract your me right now you look at us, we'll be able to extract I mean, this is possible now, but it hasn't really been streamlined. And you got to be able to get a rough model of your face that moves with your face. And you can track and new lighting.

Alex Ferrari 17:24

Oh, yeah. And DaVinci Resolve has its some the facial recognition and the tracking on it is insane, you literally could start pulling out the bags under my eyes. And I mean, it's pretty insane. But if you don't have that skill set, it is going to cost money and plenty of it, you know, either put those tools in your toolbox, or just like the dam seeing properly.

Steve Katz 17:46

Right, right, right. Well, I well in the da Vinci. That's, that's great. And it's also beauty box, a number of things out there that do similar stuff. That's a 2d, facial recognition. And it works, you know, through a certain amount of rotation. But I'm talking about doing in 3d. So I would get everything would get the headphones that you would give it would be a rock, you could you could substantially rely.

Alex Ferrari 18:09

You could but that's really costly.

Steve Katz 18:11

That is costly now, but what's costly today in four years will be free from Blackmagic. feature.

Alex Ferrari 18:19

I'm serious in the in the new resolve backwards, right, and then you resolve packets. Now how should a director break down a screenplay? I think that's something that it's really not taught. And it's something that directors really don't even think about, like when you read a screenplay, for the first time what a director should be doing in actually breaking it down. Because I've taught I've spoken to a lot of Craftsman PDR directors who are just craftsmen, they just understand the process. Yeah. And they have specific like, okay, boom, boom, boom, boom, it's almost created. It's almost it seems almost non creative. But it is creative, because it's almost like a blueprint. But how would you suggest that?

Steve Katz 18:57

Well, first of all, I think that very important to do a table read. And to get your actors, if you if you're that powerful, if that's in the budget, whether they're available or not, sometimes those things aren't the case. But before you're shooting, because you when you hear your dialogue the first time, it's a very different thing from your actors. It's always a surprise, and you have to adjust. So I think that that's usually the first step, even if it's just a couple of table reads, maybe only partial cast. But once you have that down, then you start with your script. And now this is Judith Weston has written a terrific book about preparing probably the best by far the best one, in fact, on the subject, but it's very actor driven. It's not really visually driven. So since I mostly write about the visual side, even though I have gone to acting classes and gone through and done a fair amount of that kind of those kinds of workshops, visually when you break it down, you're you know, you are drawing little boxes in the margins of your script. And you're you know, you're closing your eyes. You're going through it line by line and whose took no? Is this a close up? I mean, usually no kind, okay, you were to dinner scene. And let's say that's a simple one because people who see it and so you're looking at that and you get to break that down. So that probably means you're going to do over the shoulder shots and reverse shot reverse pattern. So they that's, that's kind of set for you. But at the same time, you may want to move the camera at some point you want to know, do you want to do a two shot and what a lot of directors do, and even Spielberg and others and many have, they built the screen other films. And at this point in their career, once they've been doing it for a while, this is less of an issue. But I know Phil was talking about looking at films at night when he was doing close encounters. So you kind of look and you'll get a sense of how a basic style for the film. So Gordon Willis the DP for let's say godfather did things differently with different lenses than say St. Martin comedy. So he in which they're using much wider lenses. So you get your so you listen to the actor, you got to get a new sense of your what your dialogue sounds like and how people play together, then you have sort of a sense of the style, it's been slightly longer lenses is a comedy going to why you're gonna exaggerate and then you're gonna sit down, and then that's the line by line. And because you let an actor speak to hold on to the whole scene, indicating cuts is not really all that critical. Because I've set up a an idea or a scene that's primarily, you know, locked into over the shoulders and such because you're not moving but um, then you go line by line and on an emotional basis, you have to sit, you know, who's who is what line has to be emphasized what doesn't. So I go for the emphasis in the line, I go for turning points in the drama. And I really sort of do what would be a description of the flow of the scene, because a scene has a beginning, middle and end. And you have to identify one the most important, a lot of this is for the actors, it's not really just for its for In other words, it's what I need to be able to say the actors and breaking it down, I'd also have notes for the actors, what intention, can I give them, what it because you don't want to say, move to the left, and Ray and do this and sometimes do that for an action, but you don't do it for performance. So in terms of breaking the script down that I you know, I usually go through and just a lot of notes in the scripts, and then I retype it separately outside the script, and give myself a little bit more room for for doing storyboard panels. And, you

Alex Ferrari 22:34

know, so the one thing that you were saying, in regards to coverage and things like that, and you have over the shoulders and things, I've noticed that a lot of young film directors, myself included, when I was starting out, we tend to kind of try to do these Scorsese style shots, or these kind of, you know, Spielberg esque kind of shots, which, you know, they're either very convoluted, I'm going to reflect off of this light, and I'm going to do it Yes, lossky over here, then I'm going to grab a Hitchcock and a Truffaut over there. And like they do these kind of insane amount of, you know, visual, and I hate to use the term but visual masturbation almost. Yeah. And in the sense that it's not propelling the story. It's propelling the ego, but it's not propelling the story. What's your experience on that? Because I think a lot of first time directors that I've seen and I did again, I did it myself is we go to so complex when you when you bring that kind of that kind of shots or shots to a seasoned dp or seasoned first ad, they just look at you going Alright, good. Yeah, it because I feel it's just not moving the story for it because shots should move the story for so forth. The question basically is when should you move the camera and why should you move the camera? And, you know, kind of goes along with that first question.

Steve Katz 23:53

Right? Well, I think you're right back what Orson Welles did Citizen Kane, you know, that was the that was the movie that even in its day, the the critics were saying wow, he there's so much technique exposed here that we hadn't seen before drawing attention to how it's put together with all these you know, aggressive techniques. And but today that's that's the way things are that's sort of the base level Ambien is you know, there's going to be a lot of technique and so you're absolutely correct every wants to do the vertigo shot once in their in their career, you know, the zoom and the push in and all those and there's a lit there's a long list and actually there's books that even from Michael we see about the 100 most important shotguns Yeah, it's like well, okay, that's fine, but that doesn't really help you do a scene you know, for me this what kind of director are you I I'm I love technique. But at the same time, it's the story is everything for me, I have to get that part right and that's not easy. So I don't want to have to add burden myself with a lot of exercise but really, um, you will know when the way you You won't know, but you'll learn when the time is to do something more, it has to have a really, really, really good reason for being there. And how do you know, you do it by continually going back? Am I telling the story, you remember, you know, that was you analyze it, as I mentioned from really, from a line and, and, and a emotional arc point of view, then you've kind of you get that into your head. And that's that's kind of what you're doing. That's the highway you're on. You're not it's not a highway to technique, it's a highway to the story. And then you build from there. Now Now, one other thing that you mentioned, the shots where they're aggressive, technically, but there's also something which is the sequence shot because the opposite of you know, doing something with a lot of special techniques is coverage. Well, there's also the master shot, which has disappeared Spielberg is you know, one of the few who still does it, where he'll do a scene without a lot of cuts, you know, when he'll move his actors instead of the camera. You don't see that much of that today. I remember when I saw the second matrix, I was the all the visual effects scenes, all the action scenes look great. And then they had really boring and not particularly well done scenes, but with your dialogue scenes, they're like, wow, that's that's kind of, you know, all that doesn't really live up to the rest of the movies. So But anyway, in terms of sequence shots, I like sequence shots, because I think some people overcut and and producer investors and such, you're nervous about it, because it doesn't give them room to make changes later, once you do a sequence shot, it's very difficult to suddenly cut into a medium or a close up, it looks it just breaks the whole, the whole mood. So it's kind of a one or the other scene and one of the other way to do things. But that that falls into the category of being something that, you know, people trying to do a complexity choreograph scene, well, sometimes it's a really good emotional story reason for doing that.

Alex Ferrari 27:02

Right? And maybe if you go back and look at Scorsese's, I'll bring up Marty's work at first place. Like if you look go back to the taxi driver, where there's so many shots that we you know, as filmmakers, because that's, you know, the prerequisite you have to watch taxi driver, if you're a filmmaker and we get most of Scorsese's work if you're if you're a filmmaker, but you go back and you look at the stats, some of those shots that people want to grab on Raging Bull that you want to grab. When he does it. There was a really good story point for him. It's not just like when he does that nine minute no cut Goodfellas shot. Yeah, you know, going through it completely is about telling the story. But he does it in a unique way as opposed to sometimes I see filmmakers will just try to replicate a shot purely to say that they replicated the shot, right like this. The jaw shot the the vertigo shot, which everyone thinks Spielberg came up with it. But I think it was. I think it was Hitchcock first if not even before vertigo. Yeah. Yeah. But the way he did it on the beach with this event, how many times we've seen that. And sometimes it's appropriate. I've seen it and I'm talking about major television shows major Yeah, movies, sometimes it's appropriate. Sometimes it's not. But you know, that's a director going, I need my Spielberg shot. So I right. It's, it's, it's what we do, we're you know, we, we pay homage as much as we can. But if you go back and actually study, all of those guys, all of them will have a very specific story point to them. And it's not just, I can do this because I can do this.

Steve Katz 28:32

Yeah, and Spielberg never moves the camera unless there's a reason for it in the story. It's just that he thinks in a way of telling a story in a nonverbal way much of the time, and that forces those things. But yeah, all the all the great directors of the 70s were terrific craftsman. And but they were all story driven. The whole I don't think they knew or were you trying to achieve something that was technically that? I hope you're able to cut this

Alex Ferrari 29:03

No, no, we leave it we let it go flying, sir. Go ahead. Oh my god. It's like so

Steve Katz 29:10

anyway, so those those guys were all very, very disciplined. But they had stories they wanted to tell they, they didn't have a problem with a finding material. And so anyway, I think that you know, you know, you're probably doing too much with the camera. If you ask yourself, what, how is this helping this moment? Well, I'll read these few sentences here. I'm doing this with the camera. Is that really the best thing to do? And so if you go through your own stuff, I suppose in a day so we're doing you know, here's how to conceive and I'm talking to my dp now, and you know, and I write down a list here these five techniques I want to go on I want to circle at the table where these people is the card table. Five people playing poker, do the camera with a 360. That's a nother cliche and seven then you would have to ask well what's being said, why are you doing it? And there may be a good reason. But then sometimes there isn't. But I'm not sure that people who want to do it in the first place, are that attuned to the drama anyway, I mean, I know a lot of young filmmakers who are really interested in the technique, they're really more like DPS, and the story, and they want to do the story, but it's not the characters and you talk to them. And it's just not the first thing on their mind.

Alex Ferrari 30:24

You know, right, which isn't, which is insane. That tells you something right there. So we'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. Now, I come from the story side, right. And most good directors and good filmmakers come from the store side, because we're here to tell stories, we're not just here to make a music video. I mean, if you want to do technique, go to make a music video, right? Make a commercial, you know, go make an art piece, where you can throw the camera around. And in today's tech with today's technology, that I mean, things that used to cost a lot of money to move that camera, and you literally could do now for a few 100 bucks, crazy, it's insane. It's insane. You could do a 120 minute, you know, non cut movie fairly, fairly easily, early on, on a technical standpoint, not on a choreography standpoint, but on a technical standpoint, you can get somebody to walk around with it. And I've had many filmmakers who've done that on my show. Where before that I mean, what would Hitchcock did with rope. I mean, that was a thing you could it was very, very difficult to move that camera and keep it going and to do tricks and all sorts of things. Well, then you couldn't go continuously because you had to change magazines, 10 minutes, every 10 minutes, you had to change the magazine. Now I wanted to I wanted to talk real quickly about the director on set. And I always try to tell people this one when I have young filmmakers talk to me is understand that, do you have different department heads? So you have your your dp your production design? Those are the two biggest collaborators on a technical standpoint on the set? Would you agree with that? I mean, of course, there's costumes and, and then their sound and, and first ad. But if you don't have if you have not done your job properly as a director, by casting your crew, I call it casting your crew, if you don't have a good working relationship with them. They will smell you your insert, insert uncertainty, or uncertainty about what you're doing. And many times then everyone else's agenda starts to fight. And it takes over and then you got Yeah, you got all this all these things coming at you. And it's really difficult for us, especially a first time director to even deal with that. So how what advice do you have when you have a rogue crew who doesn't respect you as a first time director, and is going off trying to do their own thing or have their own agendas? And like the DP is like, well, this movie's gonna blow. So I'm just gonna create something real. I mean, that I mean, I've seen that happen. So what's your opinion on that?

Steve Katz 32:56

Well, I think it's, um, you're asking me what happens on the day of the shoot, and it's already too late. So if this is something that you're done, yes, it's fixed by preventative medicine really, is you come in prepared. And that's what a director's it. That's what he has to do. And he has to do it with the individual members of department now on set. I mean, it just becomes a political issue. You get everybody together. And you know, I suppose you just say, Look, guys, here's what I see what's happening right now. And here's my agenda. For the end of the day, here are the things I want to accomplish. Let's figure out how we can do it and I need so less conflict so that you could do but the best way to to not be discovered as really not being prepared is to be prepared. So it's, you know, it is the script breakdown. It is a shot list. And, you know, and storyboards. If you can do it, you know, storyboards don't have to be that difficult. You know, for many, many things. You can go you can even do a rip ematic if you had Oh, I remember rip ematic II

Alex Ferrari 33:51

some people over Appomattox, I use I did a bunch of those. Those are fun.

Steve Katz 33:54

Sure, well, you've aIIow if you want well, that usually done to sell the picture movie, oftentimes, but you can use it for anything. And the basic idea nowadays and with live action, at least, is that there's so many action pictures and so many explosions that you can actually make a trailer for a movie. And if you're really good at it, no one will know that it's it's it's pieces. It's Frankenstein. It's made up of pieces of like nine different movies. And you can do this I mean, you know, how many times is New York been blown up by aliens or, you know, in superhero movies, New York and San Francisco and when a building goes over, if you needed to come up with your own movie, when that you've got a city destroyed, you can get those shots no one will ever know when you can color correct and do things so but you could do the same thing. Rip ematic for a scene you could and it's basically you goes to LA when I've got people sitting at a table how many times it has been shot in a movie 1000 you know when I can go online, I can find that. So you find those things and then you can recut them. They don't even have to be from the same movie. They don't even have to look that close. You're just going for lenses and you're just going for framing And you could put together literally a U turn the sound off of course, and and then have pretty much most of the shots you would have for your scene. And you could probably let's say you have a for a typical four minute scene. You could go get footage from other movies that look like your movie and just cut them up and make it and once you see it, even though it might look silly, maybe you've got a girl in a guy's Park because that was the best angle you could find or whatever but you would you would suddenly Oh, okay, there is the this is long this is that, you know, I could do something else, you would get to see it. storyboards do the same thing but romantics what, you know, pretty fast. And you know, right now there's software I can go, it used to be, I have to do a screen grab from YouTube,

Alex Ferrari 35:41

right? Let's say you can just do screen grabs and paste them literally on paper for the shots that you want.

Steve Katz 35:46

You can do that too. And, or if you want to do video, video work, you know, that's that's really taking it to another level. And then you know, it sounds like I'm copying somebody, no, you're just getting a sense of this complex thing that's going to happen from these pages of paper, which don't tell you very much about what the scene is going to look like. And, you know, if you do it with actual cuts and motion, even if you only did it a couple of times, it's a great learning experience for your own. If you did you take a scenes there, how would I do this? And sometimes you can't do it, but you know it depending on what the situation is.

Alex Ferrari 36:22

And I would like to just clarify something too, for everyone listening. A lot of filmmakers like, well, I'm copying or I'm stealing from directors, I'm stealing this shot. I don't feel right about it. I'm like, we are all stealing from DW Griffith from Edison, from the guy who put the camera up and made the first medium shot, the first two shot the first over the shoulder shot. We're all copying those things, you know, so it's just what artists do everyone, to everyone. You look at what they've done in the past, there's technique. And you you know, you model yourself after that technique, and then you make it your own but a two shots a two shot medium shots a medium shot. It's not right. Right, right.

Steve Katz 36:59

And if you go look at the films for like the golden age in Warner Brothers, for example, and I loved their film work, I thought they were fantastic. And Arthur Edison and Saul Polito and Tony Gowdy and all the others who are their DPS. They have how style, they definitely have style. So if you grab any one of 250 films, the way they do the over the shoulders, the way they do the close up their phones, their singles, all that stuff is done in a way that the Warner Brothers way. Now it's not you know, it certainly MGM and Paramount did, you know, there's a lot of overlap with them as well, but Warner Brothers had a very specific look. Oh, yeah. And, you know, and the way that they move the camera was, you know, was their own? Well, you know, so they were copying themselves, they made, you know, 15 or 20 years of pictures all within that framework. So, and I learned a lot from Warner Brothers. When I was a kid, there was a studio that I most, I guess, identified with visually. So I watched those films over and over. And so that it's, I could probably say the same of Spielberg, I think that sort of his base level was Warner Brothers and universal. And they're very dramatic black and white stuff. But yeah, so but you are. So yeah, so you're gonna be copying at some level, but you're being influenced at the same time. That doesn't, once you've done once you've gotten that and you've, you've laid that down, your own personality will definitely seep into it most of the time, and your actors are going to be doing things and they're going to end you got a production designer, and all these different forces are going to, you know, basically give your whatever you're doing something that's different and unique compared to what was done in the past.

Alex Ferrari 38:40

I mean, I can I always argue him like, basically Tarantino is the greatest remix artist of all time. I mean, that's all he does. He literally take shots from movies like, and I'm not even saying omaggio literally takes them and puts them into his movies and literally takes concepts and storylines and mix but he puts it all together in such a unique and powerful way. Yes, that he is a master but he is a remix artist. Unlike anybody I've ever seen in cinema history. He is a unique filmmaker without question.

Steve Katz 39:14

Yeah. And what's interesting, what you're saying is that he is a pastiche er is at some level, but at the same time, his writing and when he worked with actors drives these stories I can remember in what was the crime thing,

Alex Ferrari 39:27

Jackie Brown? No. Oh, Jackie

Steve Katz 39:29

Brown was fantastic. That was an amazing film. But now I'm thinking of the other one with before that is first. Oh, no reservoir. Yeah. So Reservoir Dogs. And there's a scene where do the gangster friends are getting get it and they're sort of roughing up each other into the mafia is the leader of the organized crime leaders. And it's an incredibly put together scene. No one does no one else. And when I saw this, wow, that was an amazing way to write that scene. And it was something has not been done. Before it was really, I was fantastic. So that drives so anything he does with the camera is secondary. Even though even though he's he is a stylist,

Alex Ferrari 40:09

no, you can tell talentino film from frame one. Yeah, yeah. And that is something Can you define style, if you will like what like and I know that's a very difficult question to ask but like, there are certain directors and I always use this as an example to like you see a frame of Tim Burton. The our sequence you know, it's a Tim Burton movie. You see Spielberg you see a Scorsese, you see a Coppola? There are certain things, but then you see a Ron Howard movie. And I don't there's not a Ron Howard feel to it, though. He's one of the best craftsmen by far I've ever seen. So there's just kind of a distance like, you know, McTiernan, I can see I can Tony Scott Ridley Scott. I mean, yeah. Is there anything that you can suggest? I don't even know if there's a question here? Maybe this is just a conversation. But is there anything that directors can do to kind of like stamp their their style on a film?

Steve Katz 41:03

Well, that's interesting. I think by the time you get to be directing, although much younger and younger directors, you're kind of I would say you're divided. But you're either coming from a visual starting from a visual sign, or you come from an actor side. Now, Robert Altman, one of my favorite directors is not a visual stylist. But early, early on vilmos gives men shot super long lenses in mash. And you know, all men then use it for the rest of his career. But I don't think that was his idea. At least that's not what I've heard. And he adopted that. But he was only interested in the actors really, and he got these amazing performances. So that's one and Ron Howard is an actor's director. And from the time he got started, I just you know, I, we did Willow at ILM and the visual effects picture. And before that, in interviews and such, he was talking about how he learned the visual side of the business now when he said that he was probably in his 20s and he had been Opie on TV for so he'd been around the business for a long time

Alex Ferrari 42:01

his entire life almost

Steve Katz 42:02

right. So So he said, money, you know, George Lucas told him go and get a camera and shoot something. And well, that was kind of late in his career in a way when you so by personality, he was from the actor side, and not from the, from the from the visual side. So how do you become a visual person is really the question, because that's what we're talking about for style, I suppose. Although you could, you could have a style in the way you work with actors too. And that would drive some of the visual, but I think the question you're asking is, how do you become a visual stylist? Well, you kind of have to immerse yourself in and do it. You know, Spielberg was shooting from the time he was 910, or 11. Most of the most of the directors who are purely visual start very young. Because it's, it's photography for them first released, that's a big part of it. But if you want it, to develop it, you basically have to go study visual or the visual arts, you have to go and look at movies. But I hate to say this, but I think some people either have a gift for and they've done it, and they're drawn to it, or they're not. And there may be some very small percentage of that total, that totality of people who are very visual, but never really discovered it yet. And then they become visual. But by and large, I think the world is made up of the people who are comfortable, the actors and that and they're just not lining up shots. I mean, I know I've been asked to help and train people who don't come from the visual side. And at the end of the day, they kind of want to turn it over to their dp. And they want to work with the actors. So they're not looking to do. And that's how I see the world mostly in my experiences in this division. And there aren't a lot of wonderful visual stylists out there who who need to be helped to become visual stylists.

Alex Ferrari 43:49

I think you kind of grow into it. But you can be helped. But a visual stylist can be helped to be an actress, director or directors actor or actors director much easier than an actress director becoming a visual stylist.

Steve Katz 44:01

That's a fantastic point. I never thought of it that way before. But I think that's a very shrewd observation. And I think it's 100% true.

Alex Ferrari 44:08

I mean, you look at Ridley Scott's work, you know, and by the time Ridley Scott did, the dualist, if I'm not mistaken, was his first film his first picture. Yeah, yeah. He was in his early 40s and had directed commercials for 20 years. Yeah. So he knew the craft inside and out. Same thing with Fincher, same thing with Bay. Same thing with Mike Jones. And these guys, I mean, they just had so much style. I mean, you look at bay bay is just Michael Bay is all style. Yeah, but arguably, and now we're getting off the topic for a second but not on the topic. Arguably. You know, when the rock came out, pretty much every action movie after the rock. Yeah, everyone was trying to basically do what he was doing. It's kind of like what happened with iheart but like visually, I mean, if you before the rock and after the rock, which Am I am I wrong? I mean, all action movies kind of started to turn into Michael Bay. extravaganzas, he had such an impact on action films that everyone kept trying to steal from him. Am I am I right?

Steve Katz 45:06

No, I agree with that. I think he is certainly his kind of cutting. Yes, just continuity cutting. Now that it already sort of appeared known in we have traced this in the 1950s. We had it there was a you know, it was the avant garde, and we and we began to see more handheld camera and there was symbol there today. And in that was an influence to television commercials, yet less than one motion pictures in the West in general, commercial films. And but then it crept into commercials, and there were a few directors that started to do so discontinuity cutting and commercials. And that was like in the Well, yeah, I would say when it became, yeah, 80s, late 80s, into the 90s. And that that was a change. Anybody was doing that and everything, but he was doing shakey cam, and that was more like late 90s. And, and that all led to what Michael Bay was doing. Right? Without question. Yeah. And what you essentially is always trying to make order of these little shots you throwing at them. And there's a there's a higher engagement at the most base level of perception when you're doing Michael Baden because you're having to really pay attention, because it's not all making as much sense as you normally would you know what have happened?

Alex Ferrari 46:19

He's not Yeah, he's not a fan of the master shot.

Steve Katz 46:23

Rock. I'm sure I am I, you know, I liked it. We looked at Roma. And Roman is like a friend, you know, it's like, it's an incredible I know, people who said, I saw it on TV, I said, Well, don't go see t TV, go to movie theater, and sit reasonably close to the screen. So you're not at the back. And just let it sort of sweep over you because that's what you know, if you love film, and but yeah, that's that, that that kind of filmmaking is in short supply in the career

Alex Ferrari 46:49

without without question. Now, one thing I always talk to young filmmakers about is production design, and how powerful of visual style it can help you with because especially in the indie world, you know, you've basically got a white wall, and maybe a pot, maybe a potted plant. And it's not even the corner of the white wall. It's literally a white wall. And that's, you know, where the scene is taking place. And you're just going, Man, you just don't even know, a the ABCs like at least now give me some depth go back in front of the lens, give me something production is is such a powerful part of this whole process. And can you talk to talk to two people listening, what the importance is a production of dying in creating a look and creating a visual style. Because if you look at a movie, like one of my favorite movies of all time, the matrix, I mean that the production design in that movie, not to mention the visual effects and stuff in the color palette, but the color palette, all that stuff was a production design that was productions and mixed in with color grading mixed in with the lenses mixed in with everything. So can you explain a little bit about that?

Steve Katz 47:55

Yeah, well, certainly the productions is one of the key people in a film but you know, if we're talking micro budget, you can be smart for you gave me you know, example of a white room, I've got to shoot something like that myself fairly soon. So what would I do I get a quilt I put something on the wall. So one end had a painting that was red, blue, green. And on the other side of the, let's say, it's a long conference table, which is what I ought to be shooting. And you know, so yes, I will have different things on all four sides of the room, so that there'll be some geography that you can grab onto you know, where you are now, a production designer would be doing that and much more because he would not just be choosing random objects to sort of help us find out where we are he would be everything would contribute to what the story is. So What color is this thing that you're putting on the wall behind this actor? Should it be red, blue, what does that what is it representing maybe it should be neutral. Um, and a production designer goes through the entire script. And he works in a he's working at the story level. For example, in Chinatown, Richard Silbert, going to reasonably well, and Dick was a great, a great production designer and also ran a studio at one point, and it went to Chinatown. He said he wanted jack nicholson to be going uphill, much of the time when he was going to home because the detective shows you're going to one residence or location, and is often that he could, they were going up the hill and they chose locations like that because it was effortful. It was always having to make the effort. And it was a very subtle thing that was in the background. But those are the kind of global decisions that someone will make in the beginning of the thing to say okay, and they also wanted to have a lot of water motifs going through which they did you know, he sees the guy washing the car and squeaking they made a little moment and tells nothing for the story. It's just a little mood thing, but it advances the whole notion of the LA is a desert town and needs water. But the production designer is in charge of the color script. Meaning that for every location could go to eat. And in his mind, it ought to have a color and color scheme and lighting scheme to support the accent may say, Do you know this, we need to be backlit, I want to say having to be looked at the character, we can't see him so well. I want all these scenes shot like that. And so they're all these mood driven, visual decisions that the production designer will go the deep end and the editor, and the director will also, you know, have something to say, but the production designer is the guy who organizes all this. But it's, you know, it's a cost for a micro budget film, you can be smart, but

Alex Ferrari 50:37

you know, but I mean, in all honesty, though, I mean, in today's world, there is a cost. I mean, we're not trying to create the matrix, we're not building sets out. But there are there are techniques that you can create, like when composing shots, to make them more interesting, even a white room, you could throw something in the foreground, defocus it a little bit, kind of like, you know, Pan through something given a depth is something I see that younger filmmakers don't understand depth, which is a visually stimulating thing. And it could be easily like, if you're shooting in your, in your apartment in Van Nuys, and you're shooting your web series, why not put the camera in the kitchen, and shoot through all the opening all the open stuff. And then but the scenes taking place in the living room that just makes it more visually stimulating, as opposed to setting up a master shot in front of a white wall? And yeah, and they're sitting on a couch, like it's not as stimulating is not as you know, but there are things with, with composition, and just placement of camera and nine camera movement that can give you a bigger budget field you Would you agree with that?

Steve Katz 51:40

Oh, absolutely. And again, people tend to if they're not visual, they want you know, they're going to shoot someone saying something, they're going to want to fill the frame with that person. And, you know, good filmmakers know that withholding material is sometimes more compelling, and exactly what you're saying. So you've got a living room, and I'd say a medium sized apartment, you've got a kitchen, and the kitchen has got an open, you know, I will call it a window. But it is a window into the other room. So you can see someone in kitchen, they can see you, you could have someone shot and they're small on the frame, you can you know, if there wasn't the kitchen barrier in your way, there, you're doing a full shot from head to toe. And so what you're basically seeing is like he got this at a distance and me, and Okay, the audience is gonna lean forward to hear that they're going to, you know, that's going to make them engage more, it makes it feel more like a real room. And what your experience would be, if you think of it from the point of view of the point of view, that even though it's not directly a POV shot of one character, it's like, well, if I'm moving around this room, and I'm, and this conversation is taking place in real life, and I they invite me over for dinner on the third person, and I walk around and see them, you know, how would I see them. And so that would be at least one way to keep yourself honest in terms of the shot size, and how much you show or don't show because would force you probably to push things away quite a bit in stage and depth. And you know, when people can come to the camera, they can go from camera, and even not even having someone in this in the scene. So let's say you did something in the kitchen, and the guy and you know, you've got a window, but there are other barriers. And maybe you let him instead of saying oh no, you I can't see you now get back in the shot you don't go to do when you go to the fridge refrigerator tournament, let them go out of the shot. And so you still see the refrigerator door open, there's light changes of light in the room, it's going he's only gone for a few seconds he comes. that's those are things that pull you in. And you could even take it further so that the actor could go into a bathroom. Leave the door partly open. And that's a whole nother thing. So he's washing his hands or he sits on the toilet, whatever is going on. You don't see him. But the doors enough open that you can hear him.

Alex Ferrari 53:47

Right? It's Hitchcock. It says Yeah,

Steve Katz 53:49

yes, yeah. Yeah. And right. So that, yes, he would have done that, that sort of thing. And so all those things are used. But again, the technique I think that sort of gets you in that direction to say, Okay, well, let's say I'm not shooting a movie, I'm just in the scene. You know, I'm an extra person that came over to hang out with my friends. And I sit on the couch, because one guy is at the kitchen table, the other guys in the kitchen fixing food or the girls. And so I'm looking from back and forth. And okay, those are shots. How big are those shots? You know, and when this guy talks to me and says, Hey, jack, would you like a drink? And yeah, what do you want comes from the kitchen, you look, you know, those are shot sizes. And that should and then you could say, okay, that sort of sets the key signature for the eye. These are all wide medium shots. Okay, so I do that, and I can, but I'm going to need a couple of close ups. So where will I get those frames? And then then you add those and then suddenly, you've got as you're saying a space has been defined, which feels like a real space,

Alex Ferrari 54:43

right? And it's visually stimulating and much more so than just shooting against a white wall. Unless you're unless you're Wes Anderson, and then that's how you shoot everything and it's okay. Because that's a style and that's a very specific style that he has. Yeah, and it works for him. I don't know why it does, but it does work very well. I love this film. I love this film. It's just but he shoots everything like that. And even when he moves, I you saw that I saw one I forgot what movie it was where he shoots it and it's dead center. There's no rule of thirds. There's nothing. And then he pans across like to the other side of the behind the scene all over the ones and then lands in the exact same framing. It's just so wonderfully done. Was it moonlight kitten kingdom was I think it was a monkey in them. Yeah, yeah, it was. I think it was. It was just so brilliantly composed. But yeah, it's so simple. He's not a he's not a Scorsese esque moving over the camera. Yeah, it's all composition.

Steve Katz 55:39

It's like, these a little bit like a Jim Jarmusch with a little more energy. It's all flat frontal,

Alex Ferrari 55:45

and a lot and a lot of production design, a lot of production

Steve Katz 55:47

and a lot of production design. Oh, yeah. Well, and in a very stylized way, but in Kingdom. it to me, I just love the way it's shot. I mean, it's so different than I would ever think to do something, which is why I like it, I guess. But it was also driven by the script because you have bomb Baron is balla ban as the narrator. And so he comes in and so it has this odd mixture of referencing a music score and history of the island in this particular storm. And that sort of that that's part and parcel of the whole visual style is interrupting it as a sense of almost like competition you might find in a book, or in an illustration rather than in a film, or at least in class in classical Hollywood de couponer. So but yeah, he's you know, he probably the most significant stylist working in American film I mean, you we others we named have a style, but not like Anna

Alex Ferrari 56:44

Anderson's literally a frame of Anderson's Yeah, and you know, it's an Anderson film. But it's but but for everyone listening when you study, what's Anderson Look at his films are simple, but deceivingly simple because the framing is it's textbook framing, yeah. But the way he does it, and what he puts in that frame and how he puts everything centered, like that's his thing. He dead centers everything.

Steve Katz 57:09

Or does or does the the the the dolly shots are always the same? They stay absolutely flushed to the to the plane. Yes. And he'll get one moment to another moment too. And he just lays them out in a row, like the boy scout camp, which very funny, a Budapest Hotel, Budapest, same thing.

Alex Ferrari 57:25

Yeah, he's, he's wonderful. I know what look we get. We have two directors, we're going to geek out a little bit on the show, guys, I apologize. We're going to talk a little bit about it. And one other tip I wanted to throw out there. And I want to see if you agree on for low budget films, especially when you don't have a lot of productions that are your your sets aren't particularly that interesting. Using longer lenses to defocus dialogue scenes, really just adds production value. Would you agree? Yeah,

Steve Katz 57:49

I do. And and there's also that now we're talking about spatial relationships. And if you have a very wide lens, it tip for me, it takes you out of the out of the scene. And when Gordon Willis shot the Godfather, he shot slightly longer lenses for everything, I think like a 70 millimeter. Yeah, that's pretty. And so it did have a little bit of a longer feel. But once you're in the film for the whole way, you never felt like you're looking at, you know, long lenses, it just had a and what it does is it compresses the middle ground, foreground, middle ground, background and the foreground in such a way that there's more dimensional connection to the to the viewer. And when you do ultra wide, it's kind of a disconnect. And here's sort of why, if you were to sit in a movie theater, look at the screen, there is in fact, a mathematics about what focal lanes in a way that is sort of glossing over a lot of neuroscience here because we don't actually, we make a single image of lots of saccadic patterns which are moving all over the place, scanning an object, but for the perception point of view, what we think we're seeing or the way we're seeing, and if you have a very wide angle lens, then the math would say that for you to be in the right place for that lens, you've got to be you know, three rows back from the screen. And if you're doing a telephoto, you would have to be all the way at the back of the thing. So we're but we're changing lenses into movie. So there are certain lenses, what we call the so called normal lens and a little bit longer, which create a more palpable feel of spatial relationship between the viewer in the screen. And now you can break that, for example, in Orissa, in Citizen Kane, you know, we have the scene at the very end when Kane is smashing the room and the cameras put very, very very it's a super wide angle lens and we're mostly meant to have distance from him. We're separated from him but ordinarily, longer lenses a little bit longer lenses have a lot of value and I don't know why they're not used more. We tend I see you know, the iPhone automatically gives you a wide angle lens. So unless you can lengthen the phone And you're shooting with that, you're creating a very depth, the kind of spatial relationship in your shots in a way that it's not as compelling as maybe a longer lens would be.

Alex Ferrari 1:00:15

We'll be right back after a word from our sponsor. And now back to the show. But then you look at someone like Kubrick, and then he shoots with his 9.8, super wide and Clockwork Orange and shiny Oh, to amazing effect. So it really depends on the art it's always it's never the the plot, it's never the plunger, it's always the plumber. Right? You know, it's, it's always the master behind the tool, because if you give Spielberg a wide angle lens, I promise you, he's gonna make it look amazing. If it was the story.

Steve Katz 1:00:55

Well, also, it also has to do with using a wide angle lens, the further the character is, if you go you're talking about when you talk about Cuba key shooting locations rather than faces correct. And so that's a very different, that's, I would say, that's a different category of use of wide angle lens, because there's nothing that close to camera. So some of the distortion, some of the distortion goes away, it's what I was talking about creating a certain depth that was when there's a character in the scene, not necessarily a close up. And you're trying to bring them into some kind of believable relationship with through lenses in the spatial relationship, then you you know, you probably which, it's gonna say you have to shoot longer, but that's something and how would you say comfortable feel for a certain kind of scene, the wide angle would be right for something else. But yeah, nothing Kubrick getting everyday reverse shots. Right. And also auto premiered a director that's greatly underrated. He was very frontal, but he moved the camera. And so you go and look at something like in harm's way, a 1964 war picture about the aftermath of Pearl Harbor. And it's a great looking film shot by Greg Tolan who shot Shane, and it's just a it's a great look, movie. It's an absolutely great and you get to see the stage actors and to move the camera. In very, very, very few reverse shots in his style.

Alex Ferrari 1:02:22

Yeah, and look, when you look at a comedy is shot with lemon lenses, like you if you're going to do a dialogue scene, it's going to be a long lens with all the sparkling lights in the night seat behind them completely defocus as opposed to get all being unfold. That's like a romantic that's like romantic comedy.

Steve Katz 1:02:38

Yes, but a comedy comedy. A little bit flatter. Yeah, well, then, you know, they end up people end up shooting wide a lot, you know, because they think it makes it gets a character, if that's what's right for you. And all these things relate to the kind of story you're going to be doing. You know, in the old days, they shot tests for everything, every feels, you know, every every you know, every actor was shot from different lighting, or whether was Clark Gable, or Betty Davis, all those people were shot over and over again, almost for every movie, and they do all the costumes. And they would do it was black and white. And they didn't color test that came later. But yeah, all that preparation goes into kind of understanding what was the best lens for an actor or actress and anything like that today?

Alex Ferrari 1:03:22

It's sometimes at the bigger higher studio levels, when you got 200 bucks, they're gonna they're gonna do a couple of screen tests.

Steve Katz 1:03:29

that they'll do a screen test. And that's for casting, but and yes, they will go test other costumes and stuff. Yeah, right. But even there is almost like nothing as important. Because well, even today's because you can go you know, can die at later.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:43

Yeah, or, or the costume is going to be CG.

Steve Katz 1:03:48

Right, but we just have so much control now that I just find all the time people are just, they're short circuiting the process. So whether it's a script development, whether it's table reads, or whether it's, you know, production design meetings that are a little go more in depth as a collaborative effort between the creative team in advance all those things you see less of than people so I'm just gonna go make it. Right, then people go out, and sometimes they do well anyway, because the writing is good. And the dialogue is great.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:16

If you got a good script, that's always a good starting point. And if you got good actors, that's the second point. And then if you if you can make it look decent, then you've got to hit

Steve Katz 1:04:25

it. But if you do the first two, and you only do an soso job on the third how it looks, you got to you got to hit you're gonna make it work. So that's it really, it's one a single actor can carry a movie.

Alex Ferrari 1:04:37

And again, I'll go back and not to beat up Ron Howard because I actually love Ron Howard's work and he's an Oscar winning director. But he is one of those guys that his films aren't extremely visually stimulating, but his performances his stories, you look at Cinderella man, you look at beautiful mind, and they do have visual style to it to some extent, but it's not Ridley. You know, it's not it's not Scorsese. It's just not the way he directs but His story I mean, Apollo 13 just made you know, Apollo 11. Excuse me, it was amazing. You know those kind of films? And I think also he shoots a tremendous amount of courage. Oh, he's got a master series on on you. Oh no, I saw it. That's why I haven't I have not seen it. For anyone listening. That's good. It is by far the best masterclass I've ever seen. Because Ron literally says that Ron like I know him. Mr. Howard sits there and literally directs a scene from frost Nixon, which is also meant for us Nixon, by the way, is a masterclass of how to shoot a very confined space. I mean, seriously, and make it interesting. It's fascinating to watch. But he shoots this kind of walk and talk kind of scene. Seven times, I think, with different budgets in mind. So he's like, okay, so I have three cameras, I'm going to shoot and he like, literally, you literally are sitting there for an hour and a half watching one hour direct, is fascinating. It is if you just sit there going. Amazing. Okay. And if you got an indie budget, you got one camera and you've got 30 minutes to shoot, this is how I would do it. And he goes in there, and he just does it on the flies like he's such a craftsman. craftsman.

Steve Katz 1:06:07

Well, he's been doing a very, very long time. And he's a very, he's a nice guy, and I think very buttoned up as a director. So he I've seen little excerpts of it, and I and I guessed it was going to be really good. I had that feeling. But you know, I did he direct parents with this Terran hoodie Mark Parenthood, right. Yeah, he did. And I and I heard him talking about it. This is decades or 1520, whatever. We're logging tonight and released in 89. Wow. Okay. So yeah, it was a long time ago. And I heard him talking about it. And they were talking about five cameras, and five cameras. And that's a very accurate way of doing thing. And, you know, it prevents them from moving the actors. Because the actor always go in front of a camera, you know, you have a very confined space when you shoot that way. So that's something I would you know, I I don't think that way you're probably wouldn't do things that way.

Alex Ferrari 1:06:57

Well, he shot I remember him shooting far and away with Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. Well, I love that movie. That movie. He shot over a million feet of film. Yeah. Oh my god, it was so much footage. But that's how he shoots. He just shoots the hell out and covers the heck out of it. And then in Edit, he finds the performance he finds that thing that's just his style of doing it as opposed to right. Doing doing a winner.

Steve Katz 1:07:23

Yeah, right. Right. Well, Spielberg, you know, he's, you look at how much his gigantic blockbusters are, they're always 60,000,040 $50 million less than everybody else, not 200. They're like 110 at night, you know. And it's because he's just so buttoned up, both on the set and off the set. He comes in, it's or, you know, when he talks about early in his career, I think, at the ASI. There's some maybe on YouTube, where he's in a couple of classes, and he was talking about jaws and the guys who probably 25 or 26 years old, and he was a he's talking about how they storyboarded the entire film. Same thing with duel. I think there were a lot there was a lot of mostly storyboard the whole thing. He did that for the first few films. And I can remember much later in his career when he said, You know, I'm still not storyboarding, and now I'm not storyboarding everything. But that's because he had a 10 or 12 movies under his belt. Right and by that time, you know, so yeah, preparation and that's what's shot by out and selling away. You know, that if you want, all the things we're talking about don't just happen and they definitely don't just happen on the day of the shoot your first day, you know, that stuff there may be for the first day. There's weeks and weeks and weeks of prep.

Alex Ferrari 1:08:37

Yeah, without question and anyone listening please go watch Spielberg's films. Like he sees a masterclass in watching his stuff. I mean, you could still watch jaws today. Oh my God holds 110% it's in digital no CG there's no CG in it. There's nothing any still terrifying to watch and it's just such a masterclass in film directing

Steve Katz 1:09:00

it even though even the family the Americana family scenes are wonderfully you know, at the table when you know when Richard Dreyfus comes to the first time in his bed, and the three of them Roy Scheider, his wife and the other character all three are there and it's very simply shot but it's it's just beautifully shot. You know that where he pushes in when the when the boy when the sun comes in, then it's a anyway, he's certainly one he's probably the greatest living Hollywood style director out there in terms of his the precision of his work and the breadth of the of the shot flow. Now we have newer players who are you know, breaking more rules, but Spielberg has done that a little bit of himself, although I don't particularly care for it. But in some of his more recent film, he's he's resorted to some more modern techniques, but I bet you know, he's the only one doing what he did. So Well, I'd rather see that.

Alex Ferrari 1:09:55

Right. I mean, you look at someone like Nolan or Fincher, you know, both come from school of Kubrick without question or both, they both said it very frankly, their students have Kubrick's work but fit and Fincher and Nolan are extremely different in the end style and everything. But yet you can see that undertone of Kubrick and both of their works I think, Nolan more psychological and, and framing more adventure. But Fincher also was a director who directed 20 years of commercials before he ever I think it was an art Was he an art director, he started he started with Return of the Jedi as an art director at ILM, and then slowly worked into commercial work, and then became one of the biggest commercial directors ever. And then alien three, you know, seven Fight Club but you watch seven and Fight Club, which are two of my favorite films of all time. And you did that to us, Donnie? Just Yeah, yeah, style just like, oozes right off the screen.

Steve Katz 1:10:52

And Fight Club was so unusual. The Chuck apologia novel that it was that was added to all his films before that were sort of, I wouldn't quite call them genre films, but they storywise weren't breaking out anywhere near his Fight Club was really quite different.

Alex Ferrari 1:11:06

On a fight is one of my top theories without question. Perfect film. Very, very good film. Now. I wanted to ask you something you talk about in your in your book, opening and closing frames? It's something that Yeah, they don't talk in and close frames. Yeah. closers, can you please tell us a little bit about opening closed frames?

Steve Katz 1:11:25

Well, if you have a Hallmark card of snow scene with a little house, it will be a, it's framed in such a way that it's very cleanly framed, everything you need to see is right in the middle, there's a border of sort of open space around it. When we have open and close frames. And in photography, it would be like right now, if you were if I was cropped, or I was a little bit, you know. So the notion being that dumb, you're withholding more, it's more like you would see things in real life where they're Michael Kirti is the Warner Brothers director, much very responsible for the style of almost all their films was he loved was always putting things in the foreground. He was always now he didn't use open and close. I mean, he didn't use open framing enormously. But some I mean, a lot of people over frame. So in other words, start if you want to have an open and closed frame, just start looking at movies with three and four actors in the frame and see, if you see them all framed, and the two outer actors of space around them. That's, that's a closed frame. If you want to open framing, then you'll cut them off. Because that's it looks more realistic, I suppose it's more, it's more verisimilitude, ish. And so colostrum is over is over framing, it means that you're, you're leaving too much space around the actor. It's not really how we see things in real life. And if you do things where it's an open frame, where things are moving in front of you, or the actor is partly cropped out of the frame, you're you know, give me a little bit of a haircut. If there's multiple actors, that's when you really are aware of it. Because you might have the camera bisecting. So the frame is over here. And I'm on the edge of the frame or here's the end of the frame. Now, I'm not the main guy though. He's over here. But that kind of thing would be that was that a reasonably good explanation? Yeah,

Alex Ferrari 1:13:18

that explains that I'm thinking as you're talking, I was thinking of examples. So like Wes Anderson's style is pretty open. In the way he frames things, but still not overly open. But he is he would never cut a guy off on the edge like that. No, no, no, no, never in a million years will that happen? But then you look at someone like Leoni, Sergio Leoni and his framing which is I mean, epic. And like, once upon a time in the West, and I wanted the ones Yeah, once upon a time in the West, that opening sequence is that is that the movie right? Is that the right one? That like a sequence right? Yeah, when the guy gets up that is what but once upon a time in the West, right? Yeah, yeah, that opening five seven minutes is is is some of the best cinema ever shot

Steve Katz 1:14:01

is Yeah. Well, when you think about an over the shoulder shot Yeah. Where you're where you're you know, we're getting got an ear and a head that's you're cutting off the Why Why? Why we see the whole head well, because you don't need to write and

Alex Ferrari 1:14:13