On June 1st, 2020, freshly unemployed due to the sudden widespread closure of just about every movie and TV production in the world – I’m a film visualisation (previs and postvis) supervisor, more about that shortly – I decided to use my newfound abundance of time and finally take the plunge into Unreal Engine and use it to try to make a little film.

Nothing too ambitious. Three minutes, a couple of characters, no dialogue, one set. Keep it simple, you know the way.

Two years later I finished it. It was ten minutes long with five speaking characters and three settings.

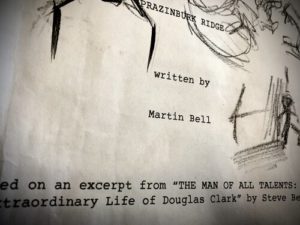

This is the story of how I made PRAZINBURK RIDGE.

Writing

I’ll be honest, I fancy myself as a writer. Always did. My brother’s one, so it might run in the family. I’ve been writing screenplays for well over a decade, I’ve had a couple of 8s on The Black List and a couple of decent competition results, and an expired option on a script.

So, on June 1st 2020, having resolved to make a film, I was exploring in my head the potential settings and scenarios that would suit a film in Unreal. I would need a setting for which there would be plenty of assets (3D models, essentially) available online – a setting that would be familiar territory for a computer game, since I was going to be using a game engine.

Sci-fi’s the obvious one, another is Fantasy. There’s countless assets like this available, and you can make it up as you go along, not worrying about things being correct to a particular period – which is handy when you’re on a budget.

But I had no story for a sci-fi film, I’d just be making something up for the sake of it – which I’m not above, don’t get me wrong. I just wanted to make something. But I didn’t have a story at all yet, so unless anything else came to mind, I figured I’d just do a short sci-fi action piece.

A war film, on the other hand… now there was an interesting idea. Not only was 1917 very fresh in my head (and on my resumé, as I was postvis supervisor on it for a little while), but there would be lots of assets on the Marketplace as it’s well-worn ground for games.

By chance, my aforementioned brother, Steve, had just written his second book that was soon to be published – a biography of Douglas Clark, a British rugby star who enlisted in World War I and ended up getting a Military Medal for bravery. I’d proof-read the book for him and remembered a couple of very exciting war sequences. I had a quick chat with him to get the nod of approval and then dug out my dog-eared A4 print of his first draft, scouring it for something that would make a good short film. And there it was, right in the middle of his book – the incident at Prazinburk Ridge, Duggy Clark’s last battle, in 1917.

Suddenly, I didn’t just have a film I could make, I had a film I knew I should make.

Previs

This can’t be a guide on how to do exactly what I did – we’d be here a long time, and I probably didn’t do it all correctly anyway. (There’s lots of guides on learn.unrealengine.com for those looking to get a taste for how it all works. I can’t promise it’s an easy thing to do if you’ve no background in 3D graphics but I can promise you that it is by far the easiest of all 3D graphics programs to get into from scratch.)

No, I want to talk more broadly about creative choices that would apply for someone making a film in any medium, and how the process of making this film fundamentally changed my life.

On early script pages you can see dialogue changes, thumbnail sketches, shot numbers, camera positions being planned…

Outside of loose thumbnails sketched on the script pages, I didn’t want to storyboard anything. I just wanted to get in there and start making shots and sequences, that’s the part of my job as a previs supervisor I love the most.

Before we go further, you may be asking, “what’s previs?”

Good question. Previs is a part of film pre-production where we basically animate and plan action sequences ahead of time, trying to nail the sequence before a penny is spent on the shoot (which gets very expensive very quickly). Here’s my reel from my 11-month stint on JURASSIC WORLD: FALLEN KINGDOM to demonstrate.

The raptor on the roof shot is still my favourite thing I’ve ever done in previs…

So anyway, I downloaded Unreal Engine, and got to work. Now, given my background (I made my first computer animation when I was 11, I’ve got a degree in Visualisation, 15 years in CGI, including 5 years as an animator and the last 5 in previs), Unreal came fairly naturally to me, and after a week or two I’d got some temp characters, a rough level, a drivable WW1 truck, and had a pretty exciting sequence coming together…

I should point out that I’ve been using Maya for 15 years and I can’t make something like this, this quickly, in Maya. That’s the power of Unreal. I’d barely started using it.

It’s worth noting that this footage, while still looking better than anything I can do in Maya, still doesn’t look as good as I wanted it to. In my head, this film should look like an almost-photoreal video game cinematic. I wanted it to look like Battlefield One, but already I knew that was unattainable by myself. I’d need help.

So I applied for a MegaGrant, which is money Epic (who make UE) give out to select creators and developers, including filmmakers, who are pushing the envelope in the engine. This would pay me for some of my time, bridging the gap in finances until the pandemic ended, and would give me a budget to hire some additional help to raise the quality. And in my naïve optimism, I assumed I’d get it. They said a decision would take 3 months. And so I got on with making previs for the entire film in the meantime.

The first edit in Adobe Premiere, July 3rd, 2020.

The first version didn’t take long, a few weeks, and I screened it for my parents and then-fiancée (now wife) once lockdown ended. They entertained it gamely, but it was a dull old affair in the first half, full of expository dialogue and with an overall lack of energy. To be fair to myself, the second half was largely the same as it is now, just without any polish.

I also showed it to a fellow previs supervisor, who said he got ‘lost’ in the first half, so I knew there was an issue there.

In my head it was obvious – the truck is here, the ammo dump is there, and the lads are moving munitions between the two. But I was learning a valuable lesson, that even when you’re working alone, filmmaking must be a collaborative effort to some degree! Somebody needs to be able to see the work at its infant stages and say, “I don’t get that bit.”

And that’s the beauty of previs. More than storyboards, where everything is static, being able to see the action play through, even rough and ugly, can really help shape decisions. I re-worked this section a few times over to make sure the story and action were crystal clear.

Another friend (a film editor) saw it and was very enthusiastic about the parts where it transitions to the rugby pitch. In this early version, the film started at the artillery battery, with the “we need more ammo!” line, and the first time we were on the pitch was after Duggy gets hit by shrapnel. My friend suggested this would carry more weight if we knew Duggy was previously a rugby star, and maybe it was worth adding a scene earlier to give the audience that information.

I loved the idea, and went about crafting a new opening with Duggy in his war uniform, saying a silent goodbye to the hallowed sports ground. But the thing that was still missing at this stage was the speech that Duggy recalls. That idea hadn’t come to me yet.

Dressed in his war uniform, Duggy says goodbye to Fartown, the rugby pitch where he played for Huddersfield…

The summer was coming to an end, TV and film productions were starting back up. My free time working on this was almost over. I’d bashed the previs into a pretty decent shape, there was a good film in there, it just needed lifting from its primordial state into something altogether more polished. And to do that, I still needed help, and a budget.

And then I got an e-mail from Epic’s MegaGrants team – they hadn’t made a decision and needed more time. They didn’t specify how long.

With work about to start back up, I decided I’d have to put the project down for a while. But I needed something to show for three months of work, so I edited together a quick trailer. Then I dressed up the shots that were in the trailer – I only picked shots that didn’t show character faces much, as they were all still intended to be temporary. I gave the characters stand-in outfits that would pass for World War I uniforms to the untrained eye, and I added rain, effects and other eye candy.

I went back to work, and in doing so I was able to ask my VFX supervisor to take a look at the whole film – the previs for it anyway. “It’s really great,” he said. “Just get it voice-overed and put it out.”

That suggestion rattled around my brain as the following year rolled on. If only it was that simple! I wanted it to look better… like a Battlefield One cinematic!

Research

Autumn 2020 was getting close, and with it came a brief window to travel. My brothers-in-law (the husbands of my wife’s two sisters) were planning a trip to Ypres, near Passchendaele, it turned out, to look at war sites. I had no idea they were war history buffs.

I hadn’t been such a buff, when all this started. There seemed to be something altogether morbid about it, and I’m a pacifist, as was Duggy – I’d always thought an interest in war suggested an interest in going to war.

I hadn’t been such a buff, when all this started. There seemed to be something altogether morbid about it, and I’m a pacifist, as was Duggy – I’d always thought an interest in war suggested an interest in going to war.

At the behest of a friend, I listened to Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History series about WW1, and was completely enthralled. I consumed any WW1 movies I could find, and picked up books about it. Pretty soon that also expanded to WW2 as well.

In Ypres, we stood at the Menin Gate while the Last Post was played each night. We looked at graves of our fellow Irish, Scottish and Yorkshire men (as we are each in turn) who never went home. We walked through craters and old trenches that still remain, and looked at rusting shell cases that still lay on the ground, over a hundred years after they fell there. It was very moving.

And, doing some detective work, I found Prazinburk Ridge, (Frezenberg Ridge, actually – the name was miscommunicated by the British soldiers and recorded incorrectly in Duggy’s diary) and the site of Duggy’s last stand.

I learned new things that affected the film in some ways. For example, the shot of a German soldier in his trench spotting Duggy’s truck through binoculars, I soon realised, was impossible – he would have been in a spotting balloon, high above the battlefield. Gas masks weren’t as I’d imagined. They had a satchel associated with them, and a pipe that fed into it.

A German spotting balloon. I bought this 3D model from Turbosquid. I hoped to rig it and simulate its ropes shaking in the wind and the rain, but ran out of time so it remained a static object.

In my spare time, here and there, I added these bits and pieces to the film. That’s actually pretty common in previs – as other departments do their work, things are re-designed, and we feed the updates into our work, and adjust as we go to accommodate them.

I’d also had the idea about the stirring rugby speech – a real speech that was given to Duggy’s British rugby team before a big game – to the opening scenes, and have him recall it later. I updated the script and felt that this new addition would really make the film sing.

But as time wore on, with no sign of any budget, I began to think that the film would never be finished. I stopped even the sporadic work I had been doing on it and left the project where it was, like an empty shell on a battlefield long after the war has ended, left to rust.

I made other, less ambitious projects, in Unreal. I worked on more films as a previs supervisor, wrote more scripts, and Prazinburk Ridge slipped from my mind, another unfinished project destined to go on the pile.

Just before Christmas 2021, I got the inevitable email from Epic to inform me that my application for funding was being turned down. By this point I had lost all hope anyway, and my finances had recovered from loss of work during the pandemic. It was the last nail in the coffin for Prazinburk.

That was that, then.

Polish

By Spring 2022, I was frustrated. After all these years of trying, I still hadn’t been able to complete a proper short film. I found myself in the same place I was back in June 2020 – trying to think of a project I could make in Unreal that would constitute a proper short film. Something that could get into festivals. Like Prazinburk Ridge could have, if it could only be finished.

Then I saw the trailer for Richard Linklater’s latest film, Apollo 101⁄2, which is actually rotoscoped, not animated, for the most part. But the effect is the same – it looks like a type of traditional animation. And a thought hit me –

Unreal can do that.

In CG terms, the process is called cel-shading. I’ve never been a huge fan of it, but Unreal can do it, and then it wouldn’t matter that half of my assets, including my characters, aren’t up to the standard of game cinematics. Everything would be cel-shaded, like a great equaliser. And if I did the film on “2s” (an old animation term meaning each frame is repeated twice, so there’s 12 drawings per second and not 24) then my motion-captured animation would be much easier to edit.

Applying cel-shading to everything seemed a bit overkill, though. There was already a slightly stylised feel to the project, the sky seemed painterly, in a way. Maybe I could lean into that. I applied a kuwahara filter to everything, which gave it that nice painterly look, and then I applied cel-shading to only specific things in each shot, exactly like in a classic cartoon where everything that moves is animated on a cel, placed upon a painted background.

Shot comparisons between first pass of previs (left) and finished film (right).

It worked. It even looked quite… nice.

I set myself a deadline. My wedding was approaching in July, and it would be great to have the film done and dusted by then.

Every spare moment I had, I spent on the film now. I got the train to Yorkshire to record a voice-over artist I wanted, and on the journey I edited audio from another actor I recorded over Zoom. I enlisted my old bandmate, Mike Payne, to compose an original score. While on my stag (bachelor party) weekend I took my laptop and worked, only stopping to party when it was appropriate. Assets I needed previously that I couldn’t find had become available to buy, including a crowd system for my rugby stadium, and a nicely accurate WW1 uniform. I ingested them hungrily, and let them proliferate through the shots. I threw out parts of the latest script that were going to take too long, including another return to the rugby ground right at the end of the film. I decided against spending time doing things that weren’t going to add to the story, like simulating the truck blowing apart at the end.

On the morning of the day I’d set as a release date, I was still tweaking shots where I could.

After the wedding, on holiday in Spain, I got my first festival decision. The film was selected for the Wigan & Leigh Film Festival, not far from where Duggy was born in Cumberland. I was over the moon.

In the end, the extra gestation time, and lack of budget, helped the film. If Epic had given me the grant in 2020, the film wouldn’t have been as good. If they’d given it to me in 2021, it wouldn’t have covered everything it needed to, as the project had grown in scope so much, so it would have probably looked like a second-rate game cinematic, and not something unique – which it is now, I think.

But mostly, that extra 18 months gave me the time to mature as a filmmaker, as both a writer and director. And it gave me the experience and knowledge in Unreal to actually execute a vision.

The moral of the story, I guess, is that everyone gets told “no” when they’re starting out. But, think about what Duggy would do: “It’s my truck, sir,” he says in the film. “I’ll bring it back.”

Go do it anyway.

Written by Martin Bell

Official Site: yescommissioner.com