MAUVAISE GRAINE (1934)

The name Billy Wilder looms large over the American cinematic landscape. Rightfully regarded as one of the finest filmmakers to ever grace the medium, he’s responsible for the creation of some of the most memorable films of Hollywood’s Golden Age- ineffable classics like SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950), DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944), and THE APARTMENT (1960).

It’s only fitting that the 20th century’s dominant art form would be sculpted in part by a man whose life story played out against a backdrop of the era’s most significant events. Unlike some of his flashier contemporaries, Wilder’s understated approach to narrative belies his reputation as a fundamental innovator in the comedy and noir genres.

He also pioneered of the idea of the filmmaker as “writer/director”– an idea that helped to usher in the auteur ere that would birth so many of our best contemporary directors. The World War II years and the 1950’s saw Wilder operating at his prime, and while he would lose some of his artistic potency in later years, he managed to establish a legacy beyond reproach as one of cinema’s greatest masters.

Born Sam Wilder on June 22nd, 1906 in Sucha Beskidzka, Austria-Hungary, the future director enjoyed a comfortable middle class childhood in a Jewish household. His father, Max Wilder, and mother Eugenia, owned a small cake shop inside the town’s train station before uprooting the whole family and relocating to Vienna in the late 1910’s.

When he decided that he didn’t want to go into the family business, he dropped out of school in favor of moving to Berlin to pursue a career as a journalist. By this time, The Great War had already been fought and won, and Germany’s economy was starting to stabilize after years of hyperinflation. He spent the first half of his twenties making ends meet by working as a paid dancing partner at dance halls and picking up the sports and crime beats for local newspapers.

It was also around this time that Wilder began developing an interest in film, spurred on by the work of German directors like Ernst Lubitsch. When Adolf Hitler was able to parlay German society’s disenchantment with its government into thrusting his Nazi party into power, Wilder saw the writing on the wall (as far as his future as a German Jew was concerned) and fled to Paris in March of 1933.

Upon his arrival, Wilder settled in at the Hotel Ansonia, which was a notorious house of refuge for other members of the German creative class who escaped fascism– people like actor Peter Lorre, writer H.G. Lustig and composer Franz Waxman. This motley crew of expats helped Wilder develop his own literary interests, one of which was a script for a feature film about the underground world of Parisian car thieves he called MAUVAISE GRAINE (1934).

Writing with Lustig and Max Kolpe, Wilder managed to hook up with producer Georges Bernier in an attempt to get the film made. For whatever reason, it was deemed necessary to find someone with previous directing experience to helm the picture alongside Wilder, and Alexander Esway was enlisted as MAUVAISE GRAINE’s co-director.

Despite his credit, it’s dubious as to whether Esway actually did any work on the film– female lead Danielle Darrieux is reported to have mentioned that she never saw him on set. Wilder would become one of the most prominent mainstream studio filmmakers of his day, but his first picture (and the first of several he’d set in Paris) was made firmly within the independent realm. The film’s low budget meant that Wilder had to make do with the limited locations and resources available to him, all while multitasking under various hats.

Translating to “bad seed”, MAUVAISE GRAINE is set in then-present day Paris, an eternal city of light enraptured by the glittering baubles of the Jazz Age. Henri Pasquier (Pierre Mingand) is a rich playboy who putters around the city in a luxury car bought for him by his wealthy doctor father. One day, however, the father decides his son should learn the value of a dollar and a hard day’s work, so he sells off Henri’s beloved cruiser and tells the spoiled young man he’ll have to earn the privilege of joyriding around the city.

Instead of getting a job, Henri decides to simply steal a car, and in the process he inadvertently falls in with a ragtag gang of low-class car thieves. Henri seems to enjoy his new life as an outlaw, and even finds love in the form of the gang’s glamorous moll, Jeannette (Danielle Darrieux), but it’s not long until he finds out the hard way that crime really DOESN’T pay.

Befitting its status as a low budget indie, MAUVAISE GRAINE’s 35mm black and white presentation is scrappy and decidedly lo-fi. However, the presence of three credited cinematographers (Paul Cotteret, Maurice Delattre and Fred Mandl) makes for a surprisingly polished lighting approach– hinting at Wilder’s big-budget studio ambitions.

This is especially evident in the low-key lighting of the climactic Avignon car chase, the murky shadows of which foreshadow future Wilder’s innovations within the burgeoning noir genre. His square 1.37:1 frame frequently showcases 2-shot masters with little supplementary coverage, strategically saving his close-ups for maximum dramatic impact.

While there are a few moments of subtle dolly work, for the most part Wilder chooses to employ a stationary camera in a bid to emphasize the performances. Part of the overall rough-hewn image is a result of the deteriorated state of the film negative, but the real world locales also lend a hefty degree of narrative grit.

Wilder naturally had to make do with several lo-fi techniques to tell his story– because his budget didn’t necessarily allow for expensive process plates or rear projection, he would simply mount his camera on the hood of the car and instruct his actors to careen around the city for real.

While this technique might seem like simple common sense today, the dearth of poorly-funded independent films during the Golden Age of cinema meant that the practice was pretty much unheard of. Wilder’s fellow Hotel Ansonia expat Franz Waxman collaborates with Allan Gray on the brassy, orchestral score, which unfurls without a break from start to finish.

Despite being made nearly a decade before Wilder’s true maturation as a director, MAUVAISE GRAINE hints at several thematic conceits that would come to comprise his signature. At 70-odd minutes, MAUVAISE GRAINE is an exceedingly brisk little caper, and its tight plotting can be credited to Wilder’s writerly discipline and disdain for indulgence.

Wilder built his career on exploring the particular characteristics of the middle class, contrasting their experience with both those higher up on the ladder and those below. However, MAUVAISE GRAINE isn’t particularly concerned with the middle class, as it was still a relatively foreign concept in the days prior to World War II.

Wilder instead compares and contrasts the privileged and working classes, showing a refined man of leisure “slumming it” with hardscrabble blue collar types who have to resort to criminality to eke out their living. This situation is exotic and exciting to the young man, who has never had to work a day in his life. Because the film is told from his perspective, the audience perceives this lifestyle as romanticized as well.

Even the film’s somewhat downer ending, where our hero and his girl have to skip town to avoid imprisonment, is slathered with a heavy of layer of idealized glamor– they’re off to exotic Casablanca, where even more adventures await. There isn’t a trace of cynicism in Wilder’s vision here, perhaps reflective of the world’s innocence and obliviousness to the world-shattering horrors of the war waiting just around the corner– horrors that would touch him on a much more personal level than most of his filmmaking contemporaries.

The French production of MAUVAISE GRAINE afforded Wilder several narrative opportunities that he would later be denied upon his immigration to America, thanks to the strict content regulations of the Hays Code established only four years prior. For instance, MAUVAISE GRAINE doesn’t shy away from letting its characters curse; indeed, it’s somewhat shocking to see the words “shit” and “bastards’ in the subtitles of an old black and white film.

Wilder wouldn’t be able to use these words in his work again until the Hays Code’s abolishment in 1968. Another example is the aforementioned ending that sees its criminal protagonist happily riding off into the sunset. This wouldn’t fly under the Hays Code, where criminal enterprise was always punished, and those who strayed from the letter of the law left themselves with only two possible fates: a jail cell or a tombstone.

MAUVAISE GRAINE wouldn’t bring Wilder much success as a working director; it would be almost a decade before he got behind the camera again. By the time of the film’s release, Wilder had already left Paris for America, where he would carve out a respectable career for himself as a screenwriter.

MAUVAISE GRAINE’s legacy within Wilder’s filmography could be positioned as a rough practice run for the stylish crime noirs that would make his name, and a safe training ground for techniques that would give us one of the most esteemed filmographies of the twentieth century.

THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR (1942)

The production of 1934’s MAUVAISE GRAINE provided a decent training ground for fledgling filmmaker Billy Wilder to hone his directorial skills, but dramatic events on both the world and personal stages would preclude him from making his next film for nearly ten years. Sensing that the writing was on the wall when Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime swept into power, Wilder fled Paris for the sunnier climes of Los Angeles.

He soon carved out a successful niche for himself as a Hollywood screenwriter, collaborating on many scripts with his new writing partner, Charles Brackett. During this time, he also married Judith Coppicus and fathered two children, Victoria and Vincent (who unfortunately died shortly thereafter). By the time he felt ready to direct his second feature film, Wilder’s life had changed quite drastically.

When we think of somebody making their “Hollywood debut” film, we tend to think of a young, hungry director without a ton of experience. At 36 years old, Wilder was certainly young, but he already had three Oscar nominations for writing under his belt when he convinced producer Arthur Hornblow Jr to let him back behind the camera. In order to guarantee himself a career as a successful Hollywood director, Wilder decided to adapt the most commercial story he could find, eventually settling on a play called “Connie Goes Home” by Edward Childs Carpenter.

Wilder and Brackett took Carpenter’s source material and turned it into THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR (1942), a lighthearted romantic comedy of the sort that Wilder would later turn into his calling card. The film is set in 1941, presenting a more-innocent America that’s yet to be scarred by Pearl Harbor and the ravages of World War II, but can still see the dark clouds gathering on the horizon.

Susan Applegate (Ginger Rogers) is a New York working girl who makes a meager living giving scalp massages to lecherous old rich men. After one unwanted advance too many, Susan quits on the spot and heads to Grand Central Station to catch a one-way train back to Iowa. She’s squirrelled away $27 in emergency cash for this very situation, but when she arrives to buy a ticket, she finds she hasn’t accounted for inflation.

Unable to afford a full-price ticket, she poses as a twelve-year old girl for the half-fare. Once on the train, she comes under the suspicions of a pair of overzealous ticket takers and hides out in the cabin of a stranger named Major Kirby (Ray Milland). Kirby is fooled by her charade, but he also takes it upon himself to act as the girl’s interim guardian, insisting she accompany him to his destination while they try to contact her mother.

Susan unwittingly finds herself at Kirby’s military base and under siege from the affections of a horde of prepubescent cadets and the side-eyed scrutiny of Kirby’s fiancee, all while falling for the dashing young Major herself.

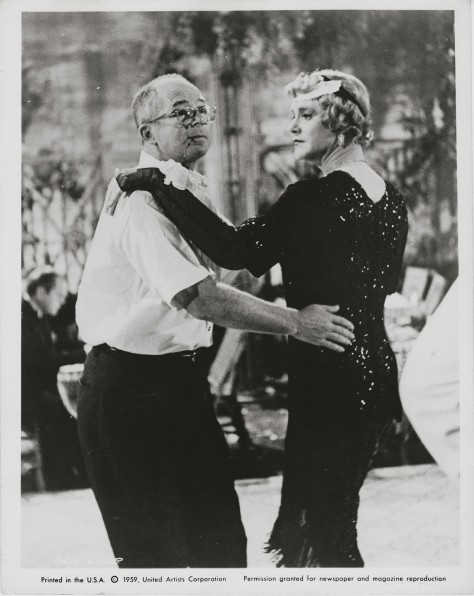

THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR’s cast is comprised of iconic Golden-era Hollywood faces. Female lead Ginger Rogers was instrumental in Wilder securing the job of director, having used her newfound clout after winning the Best Actress Oscar for 1940’s KITTY FOYLE to push the untested filmmaker into consideration. As the spunky, street-smart city girl Susan Applegate, Rogers brilliantly maneuvers a complex comedic performance that requires her to swing between a 12 year-old child and a full-grown woman at the drop of a hat.

Co-star Ray Milland more than holds his own against Rogers’ boundless energy, playing the character of Major Kirby as a decent and honorable gentleman with a bum eye that leaves him rather gullible to Susan’s fraud. His inability to correctly gauge her real age may not be the most believable aspect of Milland’s character, but his commitment to the performance helps to sell the zany nature of the plot.

If anything, the anecdote about how Milland came to be cast is more interesting than the performance itself– Wilder reportedly offered Milland the role by shouting the offer over to him in his car while the two were stopped at a traffic light.

THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR’s visual presentation represents a huge leap in quality from the scrappy, lo-fi look of MAUVAISE GRAINE. The sizable budget afforded by studio backing and the highly-controlled nature of soundstage shooting allows Wilder to pursue the glossy, polished aesthetic that was typical of Hollywood pictures of the day.

Shot in 35mm black-and-white in the then-industry standard 1.37:1 square aspect ratio, THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR sees Wilder collaborate with cinematographer Leo Tover in the creation of slick lighting setups and polished camerawork that favors static set-ups over flashy moves. Wilder mostly tends to shoot THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR in 2-shot masters to best capture the story’s physical comedy, like one would record a live stage play.

He supplements this style with an economical and minimal attitude towards coverage, employing subtle dolly work and strategic close-ups only where the story demands it. Wilder learned this approach from his editor Doane Harrison, who coached the young director on his craft throughout production. Harrison instilled in Wilder the usefulness of “in-camera editing”– the practice of pre-cutting the film in your head and shooting ONLY what you know you will need (as a way to keep outside voices from meddling too much with your vision).

Most productions shoot a lot of coverage so as to give themselves several options in the cutting room, but the technique of in-camera editing leaves the editor with only one option– the director’s vision. Due to Wilder’s success with this technique in THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR, he’d go on to adopt it in later works and develop a reputation as an extremely economic filmmaker.

Like MAUVAISE GRAINE before it, THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR is surprisingly risque considering the pearl-clutching times in which it was made, skirting around the censors by painting decidedly-mature issues like adultery and fraud in the color of family-friendly slapstick comedy.

The film is an early instance of some of Wilder’s most high-profile hallmarks as a director: tight plotting, and the presentation of complex human flaws like gullibility and willful ignorance in the context of a comedy of manners. One of the film’s key dichotomies– that of the low-class hero contending with the high-class snobbery of ignorant and out-of-touch elites– would go on to serve as a recurring thematic exploration in Wilder’s later work.

Bolstered by composer Robert Emmett Dolan’s brassy, big-band score, THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR thrilled audiences and critics alike with its bouncy effervescence upon its release in 1942. The success of the film elevated Wilder’s profile as a growing voice in cinema, opening the doors to more directorial work within the studio system and providing a pathway towards his first major work, 1944’s DOUBLE INDEMNITY.

While THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR is a lesser-known work within Wilder’s extensive filmography, the ensuing decades have seen little (if any) erosion of its original charm and wit. THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR’s artistic legacy to the medium and Wilder’s career may be… well, minor, but it does serve to reinforce Wilder’s stature to modern audiences as a first-class director of timeless, endlessly charming Hollywood entertainment.

FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO (1943)

The success of director Billy Wilder’s American debut THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR (1942) endowed the rising auteur and his writing partner Charles Brackett with enough clout to begin producing their own films with Paramount.

In the process of scouring the studio’s collection of narrative properties, Wilder and Brackett came across Lajos Biro’s play “Hotel Imperial”, and decided they would fashion it into a rousing wartime adventure picture called FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO (1943). Being the first of only two war films in his entire filmography, FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO would establish Wilder’s skills in the dramatic arena and raise his flag even higher over the mainstream cinematic landscape.

Set during the North African campaign of World War 2, FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO tells the story of Corporal John Bramble (Franchot Tone), the last surviving member of his British tank infantry, who has just emerged from the desert and been rescued by the kindly staff of the Hotel Empress Britain. Not long after Bramble arrives and recovers, the Nazis roll into town and quickly commandeer the hotel as a home base of their own.

In an effort to hide his Allied affiliations, Bramble takes on the persona of Davos, a hotel servant who was killed during a recent air raid. The plot thickens when it’s revealed that Davos was a German spy, and Bramble embraces this aspect of the dead man’s identity as an opportunity to gather valuable counter-intelligence on the Axis campaign in Egypt.

While he flits about the shadows and manipulates the German officers into revealing information, he must also disarm their growing suspicions against his true identity. Peter Van Eyck, as Nazi Lt. Schwegler, becomes the primary avatar for these suspicions, parlaying his concerns to his commanding officer, Erwin Rommel (played gloriously by one of Wilder’s personal filmmaking heroes, Erich Von Stroheim).

Bramble’s allies amidst the hotel staff include Farid (Akim Tamiroff)– the hotel owner and a constant source of comedic relief– and an elegantly pragmatic chambermaid named Mouche (Anne Baxter) who makes the ultimate sacrifice in service to the British Crown.

FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO could very well be a major influence on Steven Spielberg’s RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK (1981), but the film itself is undoubtedly influenced by the previous year’s smash hit, CASABLANCA. The arid deserts of Indio, California stand in for the fictional Egyptian sand-scapes in which FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO takes place.

When the film was made, the events depicted in the story were still unfolding on the world stage. Audiences of the time no doubt found the story to be very timely, but seventy-plus years after the fact, the heroic, rah-rah tone might besiege modern viewers with the stench of propaganda. Thankfully, Wilder recognizes some of the inherent absurdities of warfare, and takes the opportunity to milk every last ounce of comedic potential from his narrative.

Perhaps the area that sees the greatest growth of Wilder as a director is the film’s visual presentation. The first of four collaborations with cinematographer John Seitz, FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO sees Wilder expand the scope of his storytelling with dramatic compositions and confident camerawork. Shot on black and white 35mm film in the standard 1.37:1 aspect ratio, the film allows Wilder ample opportunity to experiment with the usage of shadow and light.

His delicately-sculpted chiaroscuro, like the stark overhead light from a bare lightbulb or the geometric illumination of complex window patterns, foreshadow Wilder’s coming innovations within the film noir genre while reinforcing his artistic convictions about light as a crucial storytelling tool. Wilder and Seitz employ considered dolly moves and zooms to a much more elaborate degree thanTHE MAJOR AND THE MINOR, but always in deference to character and story over flash.

One of the most notable tracking shots in FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO is also one of the most subtle– a lateral descent along the y-axis that keeps Mouche’s face centered in close-up as she walks down a flight of stairs. The shot keeps the emotional momentum of the scene going while allowing the audience to register the roiling, complex emotions Mouche is feeling as she descends the staircase to certain doom.

Editor Doane Harrison’s minimalist influence on Wilder continues to be felt in FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO, where the application of an in-camera approach to editing results in an effective and disciplined use of coverage. There are no frivolous shots that might detract from the focus. For instance, there are only 2 cutaways to airplanes flying overhead during the climactic air raid sequence.

Instead, Wilder keeps the perspective squarely on the ground, his camera following Bramble and his allies as they scurry for shelter amid the chaos. Other collaborators of note include famed costumer Edith Head (best known for her work on Alfred Hitchcock’s films), and composer Mikols Rozsa, who crafts a swashbuckling and brassy score appropriate for the film’s adventurous tone.

Despite FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO’s affectations as a somewhat-disposable adventure film, Wilder can’t help but use the story as an opportunity to further explore the idea of class conflict– a theme that Wilder would spend his career mining for material both dramatic and comic. This film meditates on the struggles between two uniformed classes: the military and hotel servants.

Both groups typically operate in service to a higher entity (hotel employees to their guests and the military to their government), but the military quickly takes on the role of pampered aristocrat as soon as they arrive. Wilder’s sympathies typically lie with the put-upon class, and FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO doesn’t break from the formula– positioning the plucky, outnumbered chambermaids and waiters of the Hotel Empress Britain as the heroes of the story.

The production’s immediate connection to the then-current event of World War 2 (which still had several years of conflict yet) can’t help but imbue the film with the manipulative air of propaganda, especially at the film’s conclusion when Bramble heroically runs off to join the British advance to victory. In a way, it’s fairly naive in its ignorance of some of the darker revelations that would come out of the conflict only a few years later.

For instance, the Nazis are depicted as civilized– if misguided patriots– of their homeland; there’s a memorable line where Rummel announces that they will conduct Mouche’s criminal trial under the Napoleonic code, just to prove that they aren’t barbarians.

Although Wilder had fled the Nazis himself and bore witness to some of their earlier atrocities, the larger horrors of the Holocaust had yet to be revealed– and his mother had yet to fall victim to them. If FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO had been made after World War 2, it isn’t hard to imagine that Wilder might’ve have painted his villains in a much more damning light.

FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO premiered in 1943 to mixed reviews, unable to achieve the same success that was bestowed uponTHE MAJOR AND THE MINOR. The bulk of the film’s critical merits went to its technical accomplishments, culminating in three Oscar nominations for Best Cinematography (Black And White), Best Art Direction, and Best Film Editing.

While FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO would quickly become overshadowed by Wilder’s bigger hits still to come, it stands on its own merits as a competently-made war film and a window into the fledgling auteur’s maturation into a confident, accomplished director.

DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944)

Of all the genres cinema has to offer, it’s hard to think of one more influential or compelling than noir. Unlike evergreen genres like comedy or science fiction, noir’s popularity is seasonal– it ebbs and flows very similar to how westerns periodically rise and fall into fashion. In a way, film noir could be seen as the anti-western; countering the latter’s sunkissed open landscapes and virtuous heroes with cramped urban environments, pervasive shadow, and compromised morals.

Noir has become so ubiquitous in both cinema and larger pop culture that we easily recognize it’s tropes and hallmarks, to the point where we feel like the idea of femme fatales and fedora-brimmed private investigators is as old as modern society itself. For a genre that trades heavily in dramatic irony, it’s perhaps fitting that director Billy Wilder – one of cinema’s most-respected comedic voices– would serve as the chief architect.

It’s interesting to watch Wilder’s third American feature DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944) now because, on first glance, the film seems so steeped in noir cliches that it’s almost laughable. It’s easy to forget that, in the context of over seventy years of noir cinema, DOUBLE INDEMNITY was actually a pioneering work in the genre– the first to use and establish these all-too-familiar stylistic conceits and imagery.

The film is regarded as one of the earliest instances of a mainstream Hollywood film exploring the opportunity and motive for committing cold-blooded murder, and Wilder and company’s unflinching embrace of the material arguably popularized the idea of a film using its controversy as a major selling point.

Based on the James M. Cain novel of the same name, DOUBLE INDEMNITY had long languished in development purgatory, placed there by the restrictive Hays Code and generally regarded as “unfilmable” due to its salacious, amoral storyline. Wilder, however, saw the property as his opportunity to break out from conventionally-anonymous mainstream filmmaking and make a name for himself.

There was just one problem: his writing partner, Charles Brackett, refused to help him writeDOUBLE INDEMNITY out of his utter distaste for the material. Wilder decided to press ahead anyway, securing the services of a new writing partner in the form of legendary crime novelist Raymond Chandler.

Their collaboration was infamously contentious, with the mischievous Wilder’s various antagonisms reportedly driving the ex-alcoholic Chandler back to the bottle. Despite this backroom drama, Wilder and Chandler emerged with a devilishly well-written script and a firm foundation upon which Wilder would build his first directorial masterpiece.

DOUBLE INDEMNITY, set in Los Angeles in 1938, tells the story of Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray)– a slick, successful insurance salesman who knows the ins and outs of his business better than anybody. We first meet him as he sneaks into his office late one night, bleeding profusely from a bullet wound as he records a confession into his boss’ dictaphone.

We then flash back a few days earlier to the cause of the trouble: Neff’s house call to the Dietrichson residence up in the hills of Los Feliz. He’s there to convince Mr. Dietrichson to renew his auto insurance policy, but instead he’s received by his client’s wife, Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck). After their first, dangerously flirtatious encounter, Neff finds himself drawn back to the house and ultimately into Phyllis’ arms.

Phyllis gradually divulges her unhappiness with her current marital situation and her attraction towards him, expressing a forbidden interest in doing away with her husband once and for all. Neff – not really of virtuous intent himself– eagerly proposes an elaborate murder scenario that would not only allow them to finally be together, but to also net a hefty payday for their trouble in the form of an insurance payout under the auspices of an “accidental death”.

As Neff and Phyllis put their nefarious plan into action, they find that the act of killing is easy enough, but the act of getting away with it is an altogether different challenge, fraught with peril, paranoia, and betrayal.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see DOUBLE INDEMNITY as it truly is: a masterfully riveting crime drama that profoundly influenced mainstream filmmaking and opened the floodgates to wave after wave of morally-ambiguous antiheroes and deceptive femme fatales. Foresight, however, is much less certain by nature, and as such, DOUBLE INDEMNITY’s pulpy story and corrupt characters provided quite the challenge when it came to Wilder attracting highly-respected talent to his cast.

After a long search for the right person to play the duplicitously debonaire insurance hack Walter Neff, Wilder found his man in Fred MacMurray. One of Hollywood’s highest-paid actors at the time, MacMurray was primarily known for broad comedies, and his appearance in DOUBLE INDEMNITY marked a rare dramatic turn that would profoundly influence the direction of his career.

His inoffensive, milquetoast handsomeness provides the perfect facade for the corruption lurking underneath– made all the more disturbing with its implication that even the most civilized, upstanding member of society carries with him the capacity for unspeakable evil.

His co-star, Barbara Stanwyck, was also one of the highest-paid actresses in the business, and her arresting performance as the seductive and conniving housewife Phyllis Dietrichson would ultimately earn her an Oscar nomination for Best Actress as well as an enviable distinction as the first true “femme fatale”. Edward G. Robinson, a well-known star of Depression-era gangster pictures, plays the supporting role of Neff’s boss, Barton Keyes.

Keyes is a fast-talking, cigar-chomping wiseguy excessively educated in the various methods one could use to kill themselves (and the accompanying success rate). Though he may be short, Robinson stands tall as a shining beacon of morality and principled decency amidst a sea of corrupt, indulgent narcissists. Finally DOUBLE INDEMNITY boasts the only appearance of notoriously-reclusive writer Raymond Chandler ever committed to film, in the form of a small cameo.

DOUBLE INDEMNITY isn’t just a showcase for Wilder’s stylistic growth– it’s the gold standard to which all subsequent noir films would aspire. Shot on black and white 35mm film in the square 1.37:1 aspect ratio by Wilder’s frequent cinematographer John Seitz, DOUBLE INDEMNITY’s striking compositions and low-key lighting setups would establish the style guide for this new genre while simultaneously harkening back to the older visual styles of Wilder’s youth, like German Expressionism.

One of the film’s innovations is the recurring motif of light streaming in through venetian blinds, casting shadows that resemble prison bars onto the characters. This technique has been widely copied through the decades, with its contemporary use by style-minded directors like Ridley or Tony Scott proving its enduring appeal.

Wilder’s actor-centric approach to directing had– to this point– resulted in fairly unremarkable wide compositions and 2-shots with spare coverage and movement. FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO (1943) saw Wilder’s first experiments with stylized cinematography, and DOUBLE INDEMNITY provides him with the opportunity to further explore his abilities in the arena.

Editor Doane Harrison’s influence on Wilder is still palpable in a minimalistic, in-camera coverage approach that supplements wide masters with strategic closeups. However, Wilder puts a lurid twist on an otherwise-pedestrian coverage by letting his closeups go on just a little too long, giving the impression that the characters are leering rather than gazing.

We also are beginning to see Wilder using his wider master shots as an opportunity to play with depth, consciously making artistic juxtapositions between elements in the foreground and the background (and often placing them both in focus).

Wilder’s reserved approach to camera movement gives the film a great deal of energy and momentum, albeit in a counterintuitive way– whereas many directors like to show off their stylistic flair by enlisting virtuoso camera movement, Wilder simply matches the motion of his camera with the motion of his subjects. His emphasis on function over flash makes for a muscularly minimalistic presentation that pulls us deeper into his story by removing extraneous technical distractions.

Wilder proves that even the absence of crucial information can be just as effective as its inclusion, as evidenced by the central murder sequence being made all the more affecting by Wilder choosing to dwell on a closeup of Stanwyck’s smiling face instead of actually showing us the murder in progress.

The film’s shadowy chiaroscuro is complemented by returning composer Miklos Rozsa’s brassy and intrigue-laden score– itself a source of controversy during the film’s making. The music may sound to us now as inoffensive and quaint in an “old-fashioned Hollywood noir” sort of way, but it apparently ruffled enough feathers to be considered bold and transgressive by the studio establishment upon first hearing it.

An unflinching meditation on vanity, adultery, and murder, DOUBLE INDEMNITY’s vice-laden narrative certainly had its work cut out for it in regards to evading complete and total evisceration by the censors. A light, winking touch was required to make the material palatable and morally acceptable to the MPAA’s professional pearl clutchers.

Wilder was in a prime position to walk that line, having cultivated over his previous works a playful approach to off-color content designed to cleverly fly under the censors’ radar. The opportunity to break new dramatic ground while seeing how much depravity he could get away with wasn’t the only appeal that DOUBLE INDEMNITY’s story held for Wilder– it also allowed him to indulge in his fascination with class systems.

Whereas THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR found comedy and romance in the divide between the rich and the poor, or FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO threw two very different service cultures into conflict,DOUBLE INDEMNITY aims squarely down the center in its exploration of the modern American middle class that was just beginning to emerge from post-war economic prosperity.

His convictions about this ascendant social group are reflected here in images that he’d later employ to much more direct effect in 1960’s THE APARTMENT– the idea of a suit as an identity-depriving uniform, endless rows of desks manned by faceless white-collar worker bees, the cramped luxury of a well-appointed bachelor pad, or even the canned domesticity of a grocery store….it’s rows and rows of identical products implying the neutered complacency of abundance.

Wilder’s insightful perception of the American middle class, seen in its earliest incarnation here, aided him throughout his career in creating some of the most effectively artful and enduring reflections of mid-century society ever committed to celluloid.

DOUBLE INDEMNITY was an immediate hit both with critics and audiences alike, boosting Wilder’s profile into the stratosphere. While Wilder was no stranger to a Best Screenplay nomination at the Oscars, the film marked the first time he’d also be honored for his direction (the film would go on to score seven nominations overall, including Best Picture).

In classic Academy fashion, DOUBLE INDEMNITY ultimately didn’t win in any category– bested at every turn by Leo McCary’sGOING MY WAY. Ever the mischievous imp, Wilder reportedly snatched victory from the jaws of defeat by sticking out his leg into the aisle and tripping the Best Director-winning McCarey as he made his way to the stage for his acceptance speech.

If it’s any consolation, time has proven DOUBLE INDEMNITY the better (and more-enduring) film, satisfying audiences hungry for complex, realistic plots where the good guys don’t necessarily always win. It legitimized noir as a genre, popularizing basic conceits like a voiceover delivered as a confessional monologue, a criminalistic point of view, and snappy dialogue.

DOUBLE INDEMNITY is the first truly great work in Wilder’s filmography, and its success would usher in a new phase of his career– one that would last over fifteen years and secure his place in the pantheon of great directors by producing several of cinema’s most beloved treasures

THE LOST WEEKEND (1945)

The year 1944 saw director Billy Wilder’s biggest success up to that point– the hardboiled noir thriller DOUBLE INDEMNITY. Of all the film’s Oscar nominations, none was perhaps as hard-fought as his collaboration with popular crime novelist Raymond Chandler on the screenplay. It’s a minor miracle that they were even able to finish the script at all, given their reportedly antagonistic working relationship.

Chandler was a recovering alcoholic, and the stress of writing DOUBLE INDEMNITY with Wilder was enough to drive him back to the bottle. This apparently hit a nerve with Wilder, who was reminded of the episode while reading Charles L. Jackson’s novel “The Lost Weekend” during a cross-country train trip later that same year.

In the book’s story of a crazed alcoholic hitting rock bottom with his addiction, Wilder saw an opportunity to explore his own experience with Chandler’s relapse– or, in his words, a chance to “explain Chandler to himself”. After he convinced Paramount head Buddy de Sylvia to secure the film rights for him, Wilder and his longtime writing partner Charles Brackett set to work adapting Jackson’s book to screen.

Wilder’s first whack at a straight-faced drama, THE LOST WEEKEND (1945) would eventually prove to be an eventful work in the director’s career, and would finally bring him the critical acclaim and awards recognition that had thus far eluded him.

THE LOST WEEKEND recounts a nightmarish, booze-soaked weekend in the life of Don Birnam (Ray Milland), a man who would be America’s next great novelist if only he could manage to stop himself from getting blackout drunk every time he sat down to write. His addiction is growing increasingly apparent to those around him, including his brother Wick (Phillip Terry) and his girlfriend Helen (Jane Wyman).

When Wick arranges for a weekend writing retreat for the both of them outside of town, Don manages to give him the slip and subsequently spends the entire weekend plunging deeper and deeper towards the bottom of a rye bottle. Don knows he’s helpless against his addiction, but will he allow others to help him before it’s too late?

Thanks to the restrictive Hays Code, the film’s attempts at authentically depicting the horrors of alcoholism are undermined by an earnestly hamfisted, old-fashioned Hollywood approach– complete with the unrealistic “Happy Ending” in which Don finally cures himself of his addiction once and for all by sheer power of will. That being said, THE LOST WEEKEND is nonetheless a powerful portrait of addiction, and served to open many audience members’ eyes to the true nature of the disease when it was released.

Ray Milland– who previously headlined for Wilder in 1942’s THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR– plays the character of Don Birnam as something of a Jekyll and Hyde type, alternating between a clean-cut, cultured, and respectable man when sober, and a tempestuously volatile drunk with a crazed glint in his eyes.

Previously known for his roles in romantic comedies and adventure films, Milland’s somewhat over-the-top performance here is a drastic departure for him. He throws himself headlong into the role, his risk rewarded with an Oscar for Best Actor. As Don’s girlfriend Helen St. James, Jane Wyman can’t help but be pigeonholed into the “glamorous, feminine saving-grace” archetype that pervades films from this era.

That being said, she turns in an admirable performance that hits all the right notes. Phillip Terry is affecting as Wick Birnam, Don’s bookish, put-together brother who is quickly becoming fed-up with Don’s unwillingness to seek help. Howard Da Silva plays a stern and vindictive bartender named Nat who somehow becomes one of Don’s confidantes.

Doris Dowling, who at the time was reportedly Wilder’s mistress, gives the minor character of Gloria a darkly seductive femme fatale flair that’s reminiscent of Barbara Stanwyck’s icy flirtations in DOUBLE INDEMNITY. Out of all the members of THE LOST WEEKEND’s cast, however, the most notable in regards to Wilder’s own personal life doesn’t even appear onscreen.

A young woman named Audrey Young was cast as a nonspeaking coat check girl, but she nevertheless managed to catch Wilder’s eye during the shoot. Young would go on to become Wilder’s second wife only a few years after his divorce from his first, Judith Coppicus, in 1946.

THE LOST WEEKEND marks Wilder’s fourth tour of duty with his regular cinematographer John Seitz, who by now has become well-versed in the director’s particularly utilitarian and minimalist aesthetic. Shot in the era’s standard 1.37:1 square aspect ratio, the 35mm black-and-white film frame boasts a glamorous, polished touch indicative of the “Silver Screen” era while alluding to the expressionist chiaroscuro that marked DOUBLE INDEMNITY (most apparent in the hospital sequence).

In fact, these dramatic shadows seem to be creeping up from the edges of the frame, reflecting the time’s growing sense of moral ambiguity and collective loss of innocence following the close of World War 2.

THE LOST WEEKEND sees Wilder further build on other stylistic conceits he’d been exploring in DOUBLE INDEMNITY and FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO (1943), like dramatic deep-focus foreground/background juxtapositions (seen most notably during a phone booth scene set in a hotel lobby), or virtuoso camera movements that aren’t always motivated by character blocking (like the Hitchcock-ian opening shot that pans across the Manhattan skyline before swooping into Don’s apartment, or the dramatic push-in to an extreme close-up of a glass of rye).

While these little moments of visual flair are indicative of Wilder becoming more secure in his technical proficiency, they are few and far between. One the whole, Wilder defers to his tried-and-true 2 shots masters, complementing them with calculating close-ups strategically placed by his editor Doane Harrison.

Miklos Rozsa, who scored Wilder’s previous two films, returns to compose the music for THE LOST WEEKEND. Typical of scores from the time, Rozsa employs a bombastic, sweeping orchestral sound with several romantic overtures that hammer home the high drama on display. This wouldn’t seem to suggest that THE LOST WEEKEND’s score was anything particularly exciting or groundbreaking– but that’s exactly what it was, thanks to Rozsa’s pioneering use of the theremin, one of the earliest instruments of the electronic variety.

The creepy, undulating sound of the theremin was used to score the nightmarish bender sequences, and its otherworldly sound would later become the aural signature of midcentury sci-fi B-films and cheesy Halloween decorations. Interestingly enough, THE LOST WEEKEND was initially released to audiences without a musical score, a version which failed to generate a positive response.

It was only after Rozsa’s score was added that the film found success (1), a testament to the transcendent quality that music can have on an image. Rosza’s work here would be nominated for Best Score at the Oscars, and while it ultimately didn’t win, Rosza could hardly have been disappointed considering he lost to himself for his work on Alfred Hitchcock’s SPELLBOUND.

THE LOST WEEKEND continues Wilder’s fascination with risque or otherwise-inappropriate content, further solidifying his artistic legacy as a filmmaker who challenged the pearl-clutching status quo and widened the range of stories that could be told in American mass media. This aspect of his career is arguably attributable to his focus on social issues directly pertaining to the middle class (aka cinema’s largest consumer group).

While alcoholism of course affects people from all walks of life, THE LOST WEEKEND’s exploration of the disease as it affects an upwardly-mobile white-collar worker helped to frame the conversation as an “everyman” issue that could happen to anybody. The film’s study of alcoholism hit a particular chord with American servicemen, who were just returning home from combat overseas and had turned to the comforts of alcohol to battle their undiagnosed PTSD.

Understandably, there were interest groups that didn’t want THE LOST WEEKEND to ever see the light of day. Paramount received enormous pressure on both sides from alcohol industry and temperance lobbyists, so the studio hedged its bets by initially putting out the film as a limited release. However, the reviews were so positive that they were compelled to ignore external pressures in favor of a wide release.

This proved to be a smart move, as THE LOST WEEKEND went on to be a great commercial success– propelled in large part by the aforementioned military audience who rewarded the film’s recognition of their plight by turning out in droves. Having endured the bitter sting of Oscar defeat with DOUBLE INDEMNITY, Wilder rode a veritable tsunami of praise all the way back to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre only a year later, sweeping up gold statues for Best Direction, Best Screenplay, and Best Picture in the ensuing riptide.

Normally, this would be the career highlight of any working director… but fate had far greater plans in store for Wilder. The crucial, artistically-validating wins for THE LOST WEEKEND would establish a firm footing for such a strong body of iconic works that his wins here look like a mere footnote by comparison.

Whereas his previous works up to this point had cultivated a reputation for Wilder as an actor’s director who emphasized writing and dialogue over visual spectacle, THE LOST WEEKEND shows Wilder comfortably settling into the height of his powers as an acknowledged master of the form.

THE DEATH MILLS (1945)

The Holocaust is easily the most horrific crime that man has ever perpetrated upon his fellow man. A genocide on the largest scale, it’s hard to comprehend or even convey the full scope of its evil. Fortunately, motion pictures have proven quite capable as a medium to appropriately hammer home the horror of these atrocities to people in faraway lands and times, in the hope that they are never again repeated.

Cinema is rife with examples both narrative and documentary–SCHINDLER’S LIST (1993) and SHOAH (1985), to name a few– but perhaps one of the most horrific displays of this genocide is also its earliest: DEATH MILLS (1945), a documentary made by renowned mainstream Hollywood director Billy Wilder.

As World War 2 came to a close and the world was beginning to find out about The Holocaust, the US Department of War was compelled to educate the German public on the monstrous actions of their former government. Towards that end, they enlisted Wilder and a co-director named Hanus Burger to create both English and German-language versions of a 20-minute short documentary.

DEATH MILLS is comprised of black-and-white film footage from the concentration camps, as filmed by those came upon them while liberating Europe from the Nazi regime. Wilder and Burger fashion these selects together into a nightmarish montage of inhumanity, unflinchingly lingering on closeup shots of mangled bodies and skeletal survivors while a somber militaristic score courses underneath.

One key aspect of Wilder’s legacy has been widening the type of subjects and stories that mainstream Hollywood deems acceptable for audiences. His previous features had pushed the envelope in decidedly adult subjects like sex and crime, andDEATH MILLS continues the tradition by forcing us to look into the cold, glassy eyes of the dead.

Despite the somewhat detached, newsreel-style narration, a quiet outrage seethes through the frame– a product of Wilder’s own personal connection to the Holocaust as a Polish Jew who fled the Nazis a decade before. These mountains of bodies are unrecognizable in death, but they were once people; HIS people. These were his town elders, his schoolmates… one was even his own mother.

Interestingly enough, the voiceover makes no mention of Jews specifically– rather, it makes the case that The Holocaust claimed people from all walks of life. This aspect of the film is consistent with Wilder’s career-long exploration of the archetypal “everyman”, the avatar through which the audience can insert themselves into the narrative and experience an intimate emotional connection.

As the first and only documentary that Wilder directed, DEATH MILLS marks a distinct step back from the glamorous Old Hollywood aesthetic that he traded in. Granted, he may not have had a choice in the matter, seeing as he almost certainly wasn’t actually present to capture these horrific images in real time. His voice instead comes through in how the film is assembled as a portrait of mankind’s unimaginable capacity for evil– far more worse and far more real than any villain on the silver screen.

THE EMPEROR WALTZ (1948)

Director Billy Wilder’s Oscar wins for Best Picture and Best Director for THE LOST WEEKEND (1945) positioned him as not just an important dramatic director, but one of the most valuable filmmakers in Paramount’s stable. Like many other directors who’ve been bestowed with The Golden Statue, the occasion marked a profound transition in both Wilder’s artistic and personal life.

At age 40, he was just entering middle age and grappling with all the malaise and neurosis that comes with it– including a divorce from his first wife, Judith Coppicus. Wanting to capitalize on his creative hot streak, Wilder immediately went back to work with his writing/producing partner Charles Brackett on a script about American troops stationed in Europe following World War II, but his research trips to German concentration camps left him so disheartened that he abandoned the project altogether in favor of pursuing something light and carefree (1).

He felt himself longing for the Austria of his youth– long before war and depression had ravaged it to ruins– and he subsequently set his sights on a light-hearted musical comedy he called VIENNESE STORY, but would come to be later known as THE EMPEROR WALTZ (1948) (1). When Wilder and Brackett managed to secure legendary crooner Bing Crosby (who was at the time considered Paramount’s top star), the film was able to come together fairly quickly.

THE EMPEROR WALTZ represents several firsts in Wilder’s body of work– his first color film, his first film set abroad since 1934’s MAUVAISE GRAINE, and his first musical– but it’s also his first stumble after a string of increasingly solid works.

Wilder’s vision of THE EMPEROR WALTZ depicts turn-of-the-century Vienna as an idyllic, mountainous land populated by innocents untainted by the devastation of world war. Crosby is Virgil Smith, a fast-talking American salesman who’s come to town to sell a new musical playback device called The Gramophone to Emperor Franz Josef (Richard Haydn under what must be a pound of heavy makeup and prosthetics).

Virgil’s efforts are derailed when the beloved dog he’s brought along with him gets entangled in a nasty spat with a purebred poodle belonging to the glamorous socialite Johanna Franziska (Joane Fontaine). They initially don’t get along very well, but this decadent world proves as irresistible to Virgil as his soothing singing is to Johanna.

What follows is a confectionary comedy about class and old-fashioned European notions on breeding. THE EMPEROR WALTZ is technically a musical, but not so much in the traditional sense in that there are very few song and dance numbers. Instead of bombastic and expansive set pieces, Wilder takes a quieter, playful approach (like in a scene where Crosby is joined in song by a supporting chorus of his own yodels echoing off the mountainside).

To shoot his first film in color, Wilder turns not to his longtime cinematographer John Seitz, but to Oscar winner George Barnes, who had previously lensed Alfred Hitchcock’s REBECCA (1940) and SPELLBOUND (1945). THE EMPEROR WALTZ certainly resembles that old-school Hollywood soundstage aesthetic: bright lights, soft/gauzy focus, and a copious amount of rear projection process shots for “exterior” sequences.

While Wilder’s visual aesthetic is relatively anonymous by design, there are a few touches that bear his mark– such as the noir-esque light cast by venetian blinds (which looks somewhat garish when rendered in candy-coated Technicolor). There’s a distinct emphasis on lavish production values at play here, with Wilder’s camera more active than usual– he employs swooping crane shots, smooth dollies, and even high-velocity whip-pans of the type that Martin Scorsese would later incorporate into his own aesthetic.

Wilder’s minimalistic approach to coverage, as informed by longtime editor Doane Harrison, alternates between wide masters that show off the ornately stuffy production design by Hans Dreier and Franz Bachelin and sustained closeups that allow us to fixate on the tiny details of the Oscar-nominated costumes by the legendary Edith Head.

Just as he traded in his longtime cinematographer for a new collaboration, so to does he forego a musical score by frequent collaborator Miklos Rosza in favor of a regal suite of cues of Victor Young. Young’s lavishly-gilded original orchestrations mix in as effortlessly with well-known classical waltzes as they do with Gioachino Rossini’s “William Tell Overture”, employed during a comic chase sequence.

THE EMPEROR WALTZ places one of Wilder’s most prominent thematic fascinations front and center: the eternal clash between the haves and the have-nots. Whereas his previous two films tackled the American middle class (a social grouping one could describe as the “have-enoughs”), this film finds Wilder flipping MAUVAISE GRAINE’s dynamic of a rich boy slumming it with some street hoods- portraying Crosby’s Virgil as the muckety-muck everyman trying to gain a toehold in an arrogant European aristocracy.

The subplot with Virgil and Johanna’s dogs hinges on the contrasting dynamics of “the mutt” and “the purebred”, becoming a conduit for a larger exploration of Victorian social hierarchy. Crosby’s huckster character is positioned as the hero, which paints the members of the Viennese aristocracy as villains by default. The rich are also portrayed as depraved in regards to their virtues, with the money-minded, shameless social-climbing character of Baron Holenia (Roland Culver) being a particularly strong example.

Additionally, THE EMPEROR WALTZ provides ample opportunity for Wilder to indulge in the iconography of uniform– the male members of the aristocracy all seem to wear extravagant military garb while Crosby dresses himself up in a stereotypical lederhosen get-up to fit in amongst the common men from the nearby village.

For a film so admittedly inoffensive and conventional, the production of THE EMPEROR WALTZ was surprisingly turbulent. Wilder and company shot in Canada, where any cost advantages it offered over other locales were soon negated by budget and schedule overruns (1). For instance, pine trees were reportedly flown in from California and planted on-location at great expense.

Crosby was reportedly difficult during the shoot, refusing to take direction from Wilder or cues from his costar Fontaine (1). Though THE EMPEROR WALTZ was shot in 1946, immediately following THE LOST WEEKEND, the film would not be released for two more years. Wilder kept having major problems during the post-production process, one being that he apparently didn’t like how certain colors looked when they were rendered in Technicolor (1).

Though he was ultimately dissatisfied with the final product, THE EMPEROR WALTZ was received quite warmly by the critics, and would even accumulate Oscar nominations for Head’s costume design and Young’s score. Time hasn’t been as kind to the film, relegating it to the bargain bin of Wilder’s forgotten minor works.

Indeed, it’s the cinematic equivalent of candy– bright, colorful, sweet, and completely devoid of nutritious value– but perhaps that’s the point. After the shadowy gloom of both his last few films and real events on the world stage, THE EMPEROR WALTZ serves as something of a palate cleanser for Wilder and his audience. Above all, the film is a pure escapist fantasy– one that mercifully allows Wilder to return, however briefly, to a world he once loved that no longer exists.

A FOREIGN AFFAIR (1948)

The destruction caused by World War II left a profound gash in the psyche of citizens belonging to both the Axis and Allied nations. Director Billy Wilder’s personal and professional life was deeply entwined with the global conflict– not only did he hail from the regions hit hardest within the European theatre, his heritage as an Austrian Jew meant that many of his direct family members–including his own mother– fell victim to Hitler’s concentration camps.

This no doubt propelled Wilder to be particularly forceful and unflinching in his detailing of Nazi atrocities in his short documentary DEATH MILLS (1945), but it would also influence his feature work. Having been promised financial assistance from the government if he made a picture about Allied-occupied Germany, Wilder decided to expand on his research experience in talking with Berlin citizens who had been left to pick up the pieces of their ruined city (1).

He was struck by one anecdote in particular, about a woman who was thankful for the return of gas service to the city….but not so she should cook again, but because she could finally commit suicide (1).

Understandably, developing a story set in this hopeless world can be quite a miserable process, so in 1946 Wilder took some time off to shoot the romantic musical THE EMPEROR WALTZ instead. During that film’s interminable editing process, Wilder returned to developing his Berlin film with writing and producing partner Charles Brackett as well as a third screenwriter Richard L. Breen, basing their efforts around a story by David Shaw.

The resulting film, 1948’s A FOREIGN AFFAIR, would find Wilder and company actually shooting amidst the ruins of Berlin– a move that brings a stark sense of bitter reality and gravitas to an otherwise-romantic wartime comedy and reflects the collective loss of innocence that World War II sustained upon the world.

The story begins when a planeload of American diplomats arrives in Allied-occupied Berlin to inspect conditions for the soldiers posted there. Among this predominantly-male group of envoys is Phoebe Frost (Jean Arthur), a prim and proper congresswoman from Iowa who’s quick to clutch her pearls at even the slightest display of moral bankruptcy.

She crosses paths with Captain John Pringle (John Lund), a duplicitous serviceman engaged in a secret affair with Ericka Von Schluetow (Hollywood Golden Age icon Marlene Dietrich), a German showgirl with ties to prominent ex-Nazis still lurking around the city. Frost knows Schluetow is sleeping with an American serviceman but she doesn’t know the man’s identity, so she unwittingly partners with Captain Pringle– the very man she’s looking for– to bring Schluetow’s American lover to justice.

This being a romantic comedy, Frost’s close proximity to Pringle naturally causes her to fall head over heels in love with him, creating a messy love triangle that somehow manages to neutralize an insurgent threat from the Nazi party’s lingering remnants.

A FOREIGN AFFAIR is a complicated film, taking on a decidedly cynical tone that explores how people might continue finding comedy when the world has been destroyed around them. Occupied Berlin resembles something of a large-scale prison, with citizens having forsaken paper currency in favor of a barter system.

They trade their goods and services (and, as the film implies, their bodies) for small, fleeting pleasures like cigarettes and candy. The societal depravity seems to have also given way to moral depravity, which Wilder frequently alludes to with a deft, comedic touch.

We see frequent images of American servicemen riding through the city on tandem bikes, catcalling German women out on their own, or those very same German women confidently striding through town with babies in strollers garnished with little American flags– all winking references to the widespread climate of fornication and adultery that has flourished in the absence of governmental order.

The relationship dynamic between Lund and Dietrich also contains slight hints towards BDSM proclivities, creating a sense of sexual delinquency that underscores an otherwise-demure romantic comedy. A FOREIGN AFFAIR’s subject matter is indeed quite risque relative to the time in which it was made, but serves as yet another instance of Wilder pushing the envelope of what mainstream Hollywood films could depict on-screen.

A FOREIGN AFFAIR’s plot hinges upon the dynamic of the eccentric love triangle between Jean Arthur, Marlene Dietrich, and John Lund. Arthur’s naive and prudish congresswoman Phoebe Frost is the chief protagonist– a bold choice given the unfortunate fact that mainstream Hollywood traditionally doesn’t make films detailing the romantic aspirations of older women.

Wilder reportedly lured Arthur out of retirement to play the role, but her experience on set just might have caused her to regret it; Wilder’s sincere admiration for her co-star Marlene Dietrich caused Arthur to become the envious second fiddle by default (1). Dietrich, to her credit, is perfectly cast as the German enchantress Ericka Von Schluetow.

In the classic femme fatale fashion (which Wilder helped to create), Dietrich exudes an icy glamor and a weaponized sex appeal in her portrayal of a nightclub singer whose allegiance to her new American conquerors is suspect.

Having spent a great deal of World War II touring the European front and entertaining Allied troops, Dietrich was understandably reticent about taking on the role of a lusty woman with Nazi sympathies, but Wilder was able to coax her aboard with the promise of a big payday as well as the company of her old friend Friedrich Hollaender as the film’s composer and her on-screen accompaniment during singing numbers like “Black Market” (1). John Lund’s Captain John Pringle is a two-faced American soldier– he projects a somewhat dopey demeanor in public, only to switch over into a womanizing cynic behind closed doors.

Lund was a Paramount contract player whose career never really took off, and his serviceable yet ultimately forgettable performance inA FOREIGN AFFAIR would arguably become his best-known appearance (1).

A FOREIGN AFFAIR marks Wilder’s first collaboration with cinematographer Charles Lang, who would go on to helm some of Wilder’s later works like ACE IN THE HOLE (1951) and SABRINA (1954). Lang was nominated for an Oscar for his his work on this film, which sees Wilder revert back to black and white photography after his first experiment with color in THE EMPEROR WALTZ.

The 1.37:1 square 35mm film frame is awash in moody chiaroscuro, incorporating the deep shadows and expressive lighting techniques that Wilder previously used in DOUBLE INDEMNITY while translating them into the language of comedy. Wilder’s belief in the primacy of writing is reflected in his mostly-minimalistic approach to coverage (using closeups sparingly as a strategic complement to his wide masters), but A FOREIGN AFFAIR can’t help being visually striking– using the real bombed-out ruins of a major city as your backlot tends to have that effect.

Wilder mounts his camera onto cranes, dollies, and even airplanes in a bid to capture the smoking cityscape in an evocative manner. There’s also a significant attention placed on depth here, as well as a running visual motif of reflections (characters are often seen in mirrors in lieu of a coverage cutaways or reverse shots). The aforementioned Hollaender provides a bouncy, marching score that’s perfectly in-line with the militaristic iconography and moody visuals.

After the lavish musical overtures of THE EMPEROR WALTZ, A FOREIGN AFFAIR finds Wilder returning to his comfort zone of hybrid comedy/dramas. Like FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO (1943) before it, Wilder is telling a story that concerns German citizens and Nazi sympathizers. Whereas FIVE GRAVES TO CAIRO painted the Nazis as intelligent, somewhat-civilized foes, A FOREIGN AFFAIR gives the director ample opportunity to extract artistic revenge on the regime that was able to justify wiping out his family and fellow countrymen.

A deep-seated rage towards Germany drives Wilder’s vision of the film, as evidenced by an anecdote where an editorial assistant expressed pity for the people of Berlin upon seeing the dailies from the rubble-strewn streets, only to send Wilder off on a screaming fit about how he hoped all Germans would burn in hell for what they did to his family (1). Naturally, then, the German citizens in A FOREIGN AFFAIR are frequently depicted as barbaric, penniless buffoons, bearing little similarity to their refined, wealthy Allied conquerors. These fundamental differences in class are consistent with Wilder’s previous examinations of the subject, as is the usage of uniform (often military in nature) to make quick, theatrical distinctions between the various castes.

Thanks to his minimalist aesthetic and usage of in-camera cutting techniques, Wilder and his editing partner Doane Harrison reportedly completed a cut of the film only a week after principal photography had wrapped (1). This no doubt was a fortuitous development for Wilder, who was otherwise mired in a post production process for THE EMPEROR WALTZthat would last a total of two years.

As timing would have it, A FOREIGN AFFAIR debuted almost immediately after the premiere for THE EMPEROR WALTZ, giving filmgoers a double dose of Wilder within the space of a single year. The film was well-regarded in critical circles, but ultimately unsuccessful come awards season.

Wilder and Brackett were nominated once more for their screenplay, but if it’s any consolation to them, the film they eventually lost out to– John Huston’s THE TREASURE OF SIERRA MADRE– would become a monumental classic in its own right.

A FOREIGN AFFAIR was no doubt a cathartic experience for Wilder, allowing him the opportunity to exorcise his inner torment over the Holocaust by bringing the Nazis to justice in the cinematic forum. While A FOREIGN AFFAIR is remembered today as a minor work in Wilder’s canon, it’s still an important work if only for its evidence of Wilder consolidating his directorial strengths into a unified approach– an approach that, when he would next apply it, would result in one of the most classic films in all of cinema.

SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950)

When we talk about “the cornerstones of American cinema”, only a select few films lay true claim to the title– films like Orson Welles’ CITIZEN KANE (1941), Alfred Hitchcock’s VERTIGO (1958), or Billy Wilder’s SUNSET BOULEVARD(1950). These are some of the greatest films of all time, made with an impeccable craftsmanship that has endured through the decades and survived countless filmmaking trends.

Wilder in particular was hailed for his strengths as a screenwriter, and as such, SUNSET BOULEVARD arguably boasts the best writing of any film of this caliber. Lines like “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small”, or “I’m ready for my closeup, Mr. DeMille” have become ingrained into our cultural subconscious, becoming synonymous with the medium of film itself.

Despite being made nearly seventy years ago, SUNSET BOULEVARDhas lost none of its macabre, biting edge. The same underhanded promise of glamor, luxury, and fame still brings in a fresh busload of wide-eyed transplants to Hollywood each and every day.

That shimmering apparatus we call “The Dream Factory” was built by a rogue’s gallery of egotistical hucksters, craven hedonists and byzantine grotesques, and Wilder’s lifelong fascination with these shadowy figures lurking between LA’s sun-soaked avenues culminates with SUNSET BOULEVARD– a legacy-defining masterpiece that will haunt the cinema for ages to come.

As the tumultuous 1940’s drew to a close, Wilder found himself on top of the world. Not only was he an Oscar winner, he was also regarded as Paramount’s most valuable filmmaker. On top of that, he was once more a newlywed, having just married singer Audrey Young following a courtship that began on the set of 1945’s THE LOST WEEKEND.

His status as a member of the Hollywood elite meant that he spent a great deal of time in the parlors of LA’s grand mansions, some of which belonged to retired, reclusive stars of the silent era. He found himself inspired by this strange, somewhat-sad scene, and began working on a new script with his longtime writing and producing partner Charles Brackett.

They were careful to tread lightly, as such an inside look at Hollywood’s seamy underbelly hadn’t really been attempted in this intimate a fashion before. Towards this end, they enlisted the help of a third writer, D.M. Marshman, who had written a critique for THE EMPEROR WALTZ (1948) that Wilder and Brackett strongly responded to.

Despite SUNSET BOULEVARD’s nature as an insider’s industry expose, Wilder and Brackett met with very little resistance from Paramount Pictures, who even went as far as far as encouraging them to use Paramount’s real name and facilities instead of a fictional substitute within the narrative.

SUNSET BOULEVARD begins at the end, with an image of a dead man floating in the pool of a grand estate located just off the eponymous drag. The dead man is Joe Gillis (William Holden), a fact revealed to us by Gillis himself via posthumous voiceover. After setting up his current… “predicament”, he then takes us back to the beginning of his story, which finds him in the midst of flaming out of his screenwriting career.

He hasn’t booked a new gig in quite a while, and the repo men are circling like vultures around the car he’s been unable to make payments on. They finally catch up to him one day while out on a drive, resulting in Gillis blowing a tire during the ensuing chase. He escapes by rolling the car into the garage of a huge, decrepit mansion that looks like it hasn’t been inhabited for many years.

To his surprise, he finds the house is occupied by Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson), an old star from the silent era, and her ghoulish butler Max Von Mayerling (Erich Von Stroheim). When she discovers he’s a screenwriter, she offers to forgive his intrusion if he’ll give her notes on a screenplay she’s been developing on her own to serve as her grand return to the cinema.

As Gillis expects, the script is objectively terrible, but he offers to take on the task in exchange for a hefty payday and a short-term residency at Norma’s opulent estate. Growing quickly dependent on Norma for shelter, clothing and money, Gillis eventually realizes he’s a kept man— a sexual prisoner beholden to Norma’s suffocating vanity and wealth.

In a bid to reclaim his agency (and his sanity), he starts sneaking out in the middle of the night to collaborate on a romance script with a beautiful young studio reader (Nancy Olson) who he also happens to be falling in love with. When Norma catches on to Gillis’ deception, she embraces her delusion and jealousy by taking action that will bring the story back full circle to its murderous introduction.

SUNSET BOULEVARD is a brilliant portrait of Hollywood’s natural megalomania and self-deceit– traits that aren’t surprising given the fact that the entire enterprise of filmmaking could be cynically boiled down to grown men and women playing make-believe for absurd amounts of money. It’s a particularly meta example of art imitating life, but the film gains another degree of resonance in that it’s also an example of life imitating art.

Wilder’s cast is essentially comprised of burnouts, most of whom were then engaged in a drawn-out period of decline following once-lustrous careers. All four of his main cast members are playing somewhat exaggerated versions of themselves (and to their credit, each of the four were rewarded with Oscar nominations).

William Holden had been regarded nearly a decade prior as a major new talent to watch, only for his buzz to fizzle out rather anticlimactically. In that way, that experience made Holden the ideal candidate to play the talented, yet hungry, screenwriter Joe Gillis. Holden wasn’t Wilder’s first choice (Montgomery Clift went back on his original commitment to star only two weeks before production, and Wilder’s appeals to DOUBLE INDEMNITY’s Fred MacMurray were turned down outright), but his refined grit and dry gallows humor made him a natural fit for the part.

Holden’s naturalistic, low-key performance is contrasted against Gloria Swanson’s grandiose, kabuki-style theatrics. She turns in one of the most unforgettable performances in the history of the medium, channelling no less than Count Dracula in her attempt to communicate Norma’s delusions of grandeur and vainglorious imperiousness.

She slinks and slithers through the film, a vampire sucking on the lifeblood of those in her orbit to feed her own narcissism. As a former silent film star herself, Norma Desmond’s overarching attempt to mount her big comeback is a plot device that hits close to home for Swanson. She was ultimately unable to make much of a comeback herself, and would retire from the cinema altogether in 1974, citing that the only offers she received were to play lesser variations on her character here.

Newcomer Nancy Olson’s natural wholesomeness draws a nice contrast to the dusty theatrics of Norma Desmond and makes her convincing as Holden’s optimistic young love interest, Betty Schaeffer, while Erich Von Stroheim’s stern ex-husband-turned-butler Max Von Mayerling mirrors his own career trajectory as a disgraced silent-era director whose films actually featured a younger Gloria Swanson.

Finally, Wilder mischievously stunt-casts real Hollywood icons like Cecil B. DeMille and Buster Keaton to play themselves, grounding the macabre theatrics of the plot in a realistic world the audience can recognize.

SUNSET BOULEVARD is often characterized as a noir, building on the aesthetic innovations Wilder established in DOUBLE INDEMNITY. On closer look, however, it actually starts to resemble something more akin to the classic Universal horror films. The exaggerated chiaroscuro and gothic haunted-house iconography of those films are given a distinctly Californian twist, which makes the monsters residing within all the scarier because they actually exist.

After sitting out Wilder’s previous two features, John Seitz returns as cinematographer, ably capturing the director’s shadowy, monochromatic vision onto the 1.37:1 35mm film frame. SUNSET BOULEVARD sees continued instances of Wilder exploring his understated visual aesthetic, with many of his compositions emphasizing depth of focus as well as employing subtle framing devices like mirrors and reflections as a way to add intrigue while minimizing the need to cut.

Wilder’s camera is always motivated by the movement of the subject or actor, but the moves themselves exhibit a growing comfort on his part with grandeur and kinetic energy. He uses the formalistic signatures of Golden Age moviemaking (dollies, cranes, and soundstage process shots), but he also incorporates newer, less formal techniques like whip-pans during action sequences.

Seitz’s moody cinematography is given weight and authenticity by the darkly ornate production designer by Hans Dreier and John Meehan. The cavernous interiors of Norma’s mansion are depicted like Dracula’s castle, with the numerous candelabras, heavy drapes, and stone tiles choking out any natural sunlight.

This idea is further reinforced by Edith Head’s garishly glamorous costumes, which call to mind a vampire’s draping cloak just as much as they do the byzantine indulgence of the silent era. Interestingly enough, the decrepit mansion itself (of which only the exteriors were used) was not located on the titular street of Sunset Boulevard– it was instead located to the south in Hancock Park, along Wilshire.

While this fact is understably attributable to practical and aesthetic production reasons, it also points to cinema’s ability to join distant geographical points together into a convincing temporal continuity via the magic of montage.

Towards this end, editor Arthur P. Schmidt proves a capable substitute for Wilder’s longtime editing partner Doane Harrison, intuitively placing strategic close-ups within Wilder’s otherwise-minimal coverage to maximum effect. SUNSET BOULEVARD’s last shot is easily the most skin-crawlingly sublime of these close-ups, which sees the Norma Desmond character– completely surrendered to her fantasy– break the fourth wall to acknowledge our presence directly as “those wonderful people out there in the dark”.

Finally, Franz Waxman, one of Wilder’s oldest and best friends from Europe and the composer for his first feature MAUVAISE GRAINE (1934), returns with a tense score that subverts the brassy orchestral sound of Hollywood convention with a frenetic dissonance.

SUNSET BOULEVARD’s story feels just as relevant today as it did back in 1950, its timelessness owing to Wilder’s fascination with resonant thematic material. Wilder’s general approach to filmmaking reflects his belief in the primacy of the screenplay, an observation that’s supported by the fact that his protagonists are often writers themselves.

Just like THE LOST WEEKEND before it, SUNSET BOULEVARD concerns itself with the trials of a struggling young writer– a narrative device that makes for a smooth pivot to explorations of class conflict, another Wilder signature. Wilder takes every opportunity to juxtapose Gillis’ ragged poverty against Desmond’s vainglorious decadence– like his tiny, cramped apartment versus her sprawling mansion, or his car getting repossessed because he can’t make the payments while she owns an expensive antique she barely even drives.

This dynamic creates a mutually dependent, symbiotic relationship– she needs his companionship in order to perpetuate her own delusions, and he needs her material fortune in order to stave off the complete collapse of his screenwriting dreams. This burgeoning “kept boy’ aspect of Gillis’ identity becomes a major source of internal conflict for him.