STUDENT SHORTS (2003)

In 2017, Time released its annual list of the 100 most influential people in the world (2). Among the usual assortment of entertainment personalities, politicians, and various thought leaders, one name would stand out as a particularly noteworthy inclusion: Barry Jenkins, an independent filmmaker who had recently won the Best Picture Oscar for his film, MOONLIGHT (2016)— only the second African-American director to do so in the Academy’s long history.

While his ethnicity is undoubtedly an important & inextricable element of his artistry and his worldview, it could be argued that his inclusion on Time’s list was due more to his individual significance within the media landscape. To me, Jenkins isn’t just a profoundly inspirational figure who launched himself from the microbudget realm to Oscar glory, he’s also wholly representative of ideals that the theatrical medium must adopt if it hopes to survive the 21st century.

Jenkins’ cinema seems to argue for a better path, where the insatiable quest for ever-higher box office returns and the cynical catering to the lowest-common denominator is replaced by a decentralized model that favors self-expression, empathy, and community-building. Indeed, his complete lack of ego and his palpable, non-competitive passion for the work of his contemporaries shines through in his work.

From his 2008 microbudget debut, MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY, to his recent streaming series THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD, Jenkins’ work radiates compassion and love. To watch his work is to watch his empathy in action; we bear witness to a kind of unconditional love for his subjects not necessarily for who they are, but for who they have the potential to be.

Straddling the informal threshold that separates Generation X and the Millenials, Jenkins was born November 19, 1979 in Miami. He was the youngest of four children, none of whom shared the same father. His family life was anything but the nuclear ideal, with Jenkins forced to navigate a rocky relationship with a father who refused to believe the authenticity of his paternity and abandoned his mother during the pregnancy.

He grew up in an overcrowded apartment in the neighborhood of Liberty City, raised by an older woman who had looked after his own mother as a teenager. At twelve, his estranged father passed away, further isolating him within the world. Despite his hardscrabble origins, Jenkins would display his bright potential quite early.

While a student at Northwestern Senior High, he would demonstrate his inherent athleticism by running track and playing football. He also displayed an insatiable curiosity about art— specifically, cinema. He would continually raid the Foreign section of his neighborhood Blockbuster Video, gorging on French and Asian New Wave films in particular.

The sight of Quentin Tarantino on a VHS cover led to his larger discovery of Wong Kar-Wai’s CHUNGKING EXPRESS (his distribution company had brought the film to the States), which Jenkins would later credit as the “inciting event” that drove his decision to pursue filmmaking as a career.

The path to said career began in Tallahassee, where he enrolled at Florida State University’s College Of Motion Picture Arts. Jenkins thrived in this new environment, feasting on foundational texts like Walter Murch’s “In The Blink Of An Eye” and surrounding himself with like-minded people who would go on to become key creative partners— people like cinematographer James Laxton, producer Adele Romanski, and editors Nate Sanders and Joi McMillon.

This period would result in the production of Jenkins’ first serious works, a pair of shorts titled MY JOSEPHINE and LITTLE BROWN BOY (2003). Both films evidence Jenkins’ talent in its rawest form, with the growing pains that accompany the discovery of his voice’s particular contours.

MY JOSEPHINE

Believe it or not, Jenkins’ career in filmmaking was almost over before it even began. At one point in his studies, he experienced a crisis of confidence so severe he took an entire year off. As he worked through his doubts about his own talent, he began to piece together the inspiration for the short he’d make upon his return.

He was struck with amusement by his roommate’s obsession with Napoleon Bonaparte, finding himself on the receiving end of a relentless stream of arcane trivia. At the same time, he was still processing his own personal response to the world-shattering events of September 11th two years earlier; more specifically, he was interested in the fortitude of the immigrant experience in America, resilient in the face of racist hostility that now flourished out in the open under the guise of “patriotism”.

Unlike the vast majority of student films that arise from a desire to emulate their makers’ favorite works, the short that Jenkins would come to call MY JOSEPHINE is the product of genuine self-expression; it is filmmaking as an act of empathy. In using the artistic process as a means to sympathize with a worldview drastically different from his own, he finds that he and his subjects are more alike than they are different— united by the universal emotions of love and heartache and the existential alienation of their “otherness”.

That Jenkins considers MY JOSEPHINE one his own favorite pieces to this day speaks to his refreshing lack of ego. Presented entirely in Arabic, MY JOSEPHINE would rekindle Jenkins’ faith in his artistic abilities via the embrace of his visual impulses. In other words, he doesn’t attempt to overly compose the image or find “the perfect shot”; the lyrical, expressionistic style that results is pure emotion and feeling.

Shot on 16mm film, the short roughs out a simple, yet evocative sketch about an Arab-American laundry store owner (Basel Hamdan) pining for his beautiful but standoffish employee (Saba Shariat). Jenkins and cinematographer James Lanton amplify the emotionality of their subtle narrative with a high-contrast, desaturated image awash in a teal tint.

They also employ a variety of camera techniques in a bid to capture the volatile interiority of the story’s protagonist: handheld camerawork and dolly movements set the stage for a continual struggle between passion and discipline, while overcranking, slippery rack-focusing, and even a spinning “tumble-dry” effect evoke the dizzying intoxication of unrequited love. Jenkins also employs an ambient orchestral score, the distorted qualities of which foreshadow the “chopped & screwed” approach of MOONLIGHT’s music.

MY JOSEPHINE derives its title from the eponymous historical figure— the great, one-sided love affair of Napoleon Bonaparte’s life, and the one thing to remain out of reach of the man who otherwise would have everything. In transposing this framework onto the figure of a middle-class business owner, Jenkins reminds us that we are the world-changing figures of our own lives, our personal stories no less worthy of the grandness we ascribe to the major names of history.

However, MY JOSEPHINE achieves an even-more potent resonance in its narrative conceit of washing the American flag. In the years immediately following 9/11, laundry owners took to washing their customers’ American flags free of charge as a show of patriotism and solidarity. It shouldn’t be lost on us that, with the vast majority of these owners being minorities, these gestures of good faith and community-building were not frequently reciprocated.

Jenkins’ story reinforces the honorability of our immigrants— especially American Muslims, who endured no shortage of racist mistreatment as they were lumped together with a small band of extremists who did not share their values. This idea was born of Jenkins’ observation that in the modern South, being Muslim was “the new black”, but it also illuminates a more-universal truth: simply by being here, our immigrants are arguably our greatest patriots… working invisibly, behind the scenes, doing the thankless, unglamorous work of spit-polishing the American Dream.

That they don’t fit into the dominant white Anglo-Saxon paradigm speaks to the core of Jenkins’ artistic character, predicting the subsequent shape of his career as a tireless search for the dignity, beauty, and humanity of all people— and an insatiable desire and curiosity to tell the stories that mainstream American cinema will not.

LITTLE BROWN BOY

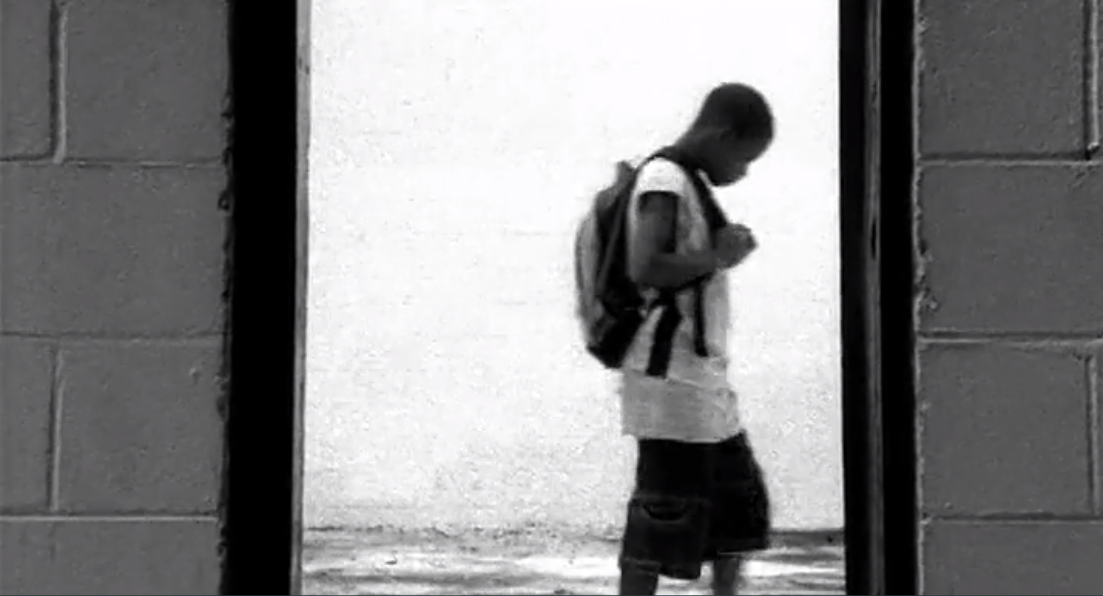

Also made in 2003, LITTLE BROWN BOY doubles down on Jenkins’ interest in stories from the edge of society. The short features DeQynn Gibson as CJ, a lonely & withdrawn boy who, given what we know about Jenkins’ own backstory, seems to share more than a few traits with his maker. He’s introduced in a rather shocking manner, witnessing a shooting during a heated argument at a basketball game and subsequently using the victim’s own handgun to dispassionately dispatch the original shooter.

This episode, however, seems to be a bit of venomous fantasy— a bitter projection of anger that’s been fostered by his solitary existence. Indeed, he seems to have no friends or family to speak of, save for a distant father who can’t be bothered to come to the phone when he calls. At 8 minutes long, LITTLE BROWN BOY is more of a tone poem than a full-blown narrative, with Jenkins content to simply follow CJ around the industrial fringes of town until the young boy discovers the unexpected beauty of ruins in an overgrown field.

Jenkins’ second student short reteams the burgeoning young filmmaker with his MY JOSEPHINE collaborators, cinematographer James Laxton and production designer Joi McMillon. The resulting style is expectedly similar to their first effort, albeit rendered entirely in high-contrast black and white.

The handheld camera is loose and restless, responding intuitively to action within the frame rather than imposing a particular style. Also like MY JOSEPHINE, a slippery, shallow depth of field continually searches for focus, echoing CJ’s tenuous grip on his surroundings. All this, combined with moments of CJ breaking the fourth wall to look directly into the lens, is highly reminiscent of early portions of MOONLIGHT— the short becomes, in retrospect, a proving ground for the later film’s animating ideas and unique tone, allowing Jenkins to test out a soulfully evocative style in a safe environment.

Despite his high-profile triumphs in recent years, Jenkins is quick to proclaim that he’s still as much of an amateur as he was during the time of these productions. What he’s really saying, though, is that he’s a perpetual student, and that seems to be the key to understanding his artistic nature. His steadfast refusal to believe his own hype has arguably made him one of the most likeable personalities in the industry.

Whereas other filmmakers of his stature tend to make grand proclamations, Jenkins uses his work to pose thoughtful questions. By actively inviting us into his artistic process, his inclusive worldview becomes all the more accessible and genuine.

MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY (2008)

While the 1990’s are often (and rightfully) regarded as a heyday for independent cinema, the late 2000’s saw the proliferation of truly indie films— a microbudget wave fostered by the rapid advancements of digital video, the rise of democratic digital exhibition formats like YouTube, and a do-it-yourself ethos that made almost any subject worth making a movie about. Soon enough, a distinct subgenre emerged: the mumblecore film.

Given critical legitimacy by tastemaking festivals like South By Southwest and Sundance as well as prominent distributors like IFC, this particular movement of American cinema is marked by a lo-fi digital aesthetic, and is mostly concerned with the low-stakes romantic exploits of upper middle-class (usually white) American twentysomethings.

Cornerstone works — Andrew Bujalski’s MUTUAL APPRECIATION, Aaron Katz’s QUIET CITY, Joe Swanberg’s HANNAH TAKES THE STAIRS — were praised for their abundance of emotional authenticity and lack of melodramatic artifice, but to those more accustomed to a “polished” cinematic experience, these works were frequently derided as needless, boring, empty, even masturbatory (in Swanberg’s case, quite literally). The general sentiment is right there in the name, dismissing a whole swath of naturalistic characters as a generation of ineloquent and inarticulate mumblers.

Like the French New Wave before it, this particular movement isn’t for everyone — nothing that merits the designation of “art” ever is — but to deny it of cinematic “legitimacy” because it doesn’t conform to cultural expectations of mainstream filmed entertainment is a form of gatekeeping. All too often, the cost and resources required in making a Hollywood-caliber theatrical feature are used as a kind of cudgel to beat back the inevitable democratization of filmmaking.

By establishing a high barrier to entry, this approach works to ensure that the industry is controlled by the whims of an elite few. The entire concept of independent cinema has always challenged this ecosystem, but mumblecore — a subgenre nimble enough to be produced on four-figure budgets in their creators’ own apartments — stood as a particularly acute threat to the status quo.

The movement is more or less extinct now, having failed to catch on in the mainstream sense while its founding fathers (and mothers) have blossomed into mature filmmakers in command of higher budgets and more-polished resources.

Director Barry Jenkins’ debut feature, MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY, is a product of the same DIY ethos & by-any-means-necessary attitude that define the mumblecore movement, but its thematic sophistication and acute focus on social justice sets it apart. If films are a reflection of their creators, then mumblecore as a whole reflects a white, relatively-privileged and over-educated segment of the artistic population.

For all their individual charms, these films reinforce the unfortunate truth that the pursuit of art as a lifestyle is a luxury afforded primarily to those who don’t have to work for a living. In contrast, by the time Jenkins sat down to write MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY in 2006 (3), he had already cultivated a substantial resume out of sheer necessity.

Within a week of graduating from Florida State University, Jenkins had already moved out to Los Angeles to work his way up the professional ladder. For the first couple years, he worked as a production assistant, most notably as an assistant to the director for THEIR EYES WERE WATCHING (2005), produced by Oprah Winfrey’s production company Harpo Film. During this time, he also co-founded a full-service production and advertising company named Strike Anywhere, which still operates today..

Only two years later, Jenkins would move to San Francisco, having decided Los Angeles wasn’t the right fit for him. Though he was drawn to the Bay Area’s film community, he mostly limited his interactions to special repertory screenings while he worked in the office of a local political campaign. MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY grew out of his fascination with San Francisco’s sociopolitical climate of gentrification and contentious racial assimilation, but found the inspiration for its narrative framework in the breakup of his first interracial relationship.

In processing his heartbreak, he came to see the episode as an opportunity ripe for dramatic exploration— and on a scale accessible enough for his limited resources. Produced on a minuscule budget of $13,000, the scrappy MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY makes up for its lack of technical polish with its fierce display of ambition and thematic conviction.

Wyatt Cenac and Tracey Heggins headline as Micah and Jo, respectively— two Black San Franciscans brought together by their shared affection for alcohol, and yet have little else in common. After a night of partying, the two strangers wake up in bed together and begin the awkward process of navigating their newfound intimacy.

As they traverse the city, visiting coffee shops, museums and each other’s apartments, Jenkins frames their fumbling romance through the multifaceted prisms of race and class. Micah is a relatively sedate young man whose passions are fired up by political and racial agitations unique to San Francisco (but have since been snaking their way to other major metros).

Stung by a recent heartbreak, he’s further frustrated by the downwardly-mobile trajectory of Black San Francisco, already massively underrepresented in a majority-white city that’s only grown richer and whiter with the arrival of Big Tech and the artificially-inflated economy that follows.

He’s also frustrated by the need to “assimilate” his racial identity into the nascent hipsterdom of his generation. Conversely, Jo has seemingly shed herself of racial preoccupations in favor of an easygoing upper-middle-class lifestyle. While Micah pays his ever-increasing rent by installing aquariums, Jo’s worry-free lifestyle is subsidized by her white art-curator boyfriend, freeing her days up to focus on her passion for making t-shirts emblazoned with the names of female filmmakers.

Though her minimization of racial identity has allowed Jo’s personal individuality to flourish, Micah perceives this as nothing less than a complete abandonment. This all leads to a cold, lopsided chemistry— indeed, there isn’t much in the way of “romance”, let alone connection. In its place, Jenkins seems to be positioning his framework as a conduit for conversation about how these disparate viewpoints can harmonize towards a better realization of racial self within an oppressively homogenous environment.

Like so many indies of the mumblecore era, MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY possesses a unique video look that has since been eclipsed by higher-quality formats. Though digital cameras that could approximate the qualities of celluloid existed, they remained out of reach for the budgets of most independent productions. As such, they used the cameras available to them: prosumer HD camcorders that could be bought off the shelf at Best Buy.

MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY employs the Panasonic HVX200, a fixed-lens HD upgrade to their wildly-popular DVX200 model, which was one of the first digital cameras capable of recording at twenty-four frames a second. Jenkins recruits James Laxton — the cinematographer of his student shorts at FSU — to perform the same duties on his first feature, resulting in a striking 1.78:1 frame that turns the perceived shortcomings of the video format into narrative assets.

The most immediate aspect of MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY’s aesthetic is its lack of color: not purely monochromatic, but heavily desaturated to the point where otherwise-strong primary colors are extremely washed out and dull. The peculiar look plays directly into Jenkins’ thematic interests, dialed back in post by editor Nat Sanders to 7% color saturation— a visual reflection of the fact that African Americans make up only 7% of San Francisco’s population.

Indeed, the only moment where Jenkins allows his image to achieve full color saturation is a short sequence shot on Super 8mm film, meant to evoke the aspects of San Francisco that evoke Micah’s affection rather than his scorn.

Because the lens was fixed to the body and couldn’t be swapped out for different glass, this generation of digital cameras limited filmmakers’ ability to fully shape the contours of their image. A few aftermarket solutions were available that offered an advanced degree of fine tuning, like the popular Red Rock line of adaptors that softened the harsh lines of video while simulating a shallow depth of field to better approximate the look of film.

Such a look present throughout MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY suggests Jenkins and Laxton took advantage of this option, which also results in a rather interesting side effect: a visible vibration at the frame’s edges, as if the focal plane was hanging on for dear life in terms of retaining its clarity. This could be considered an aberration or a defect, but it subtly reinforces the roiling tensions that course underneath Jenkins’ narrative.

MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY makes no further effort to impose a deliberate “style”, arguably a reflection of the filmmakers’ attempt to simply capture the desired image quickly with whatever resources were at hand. As such, the camerawork toggles between handheld setups, locked-off compositions, and stabilized tracking moves with little in the way of aesthetic consideration besides whatever method was best to quickly and effectively capture the shot in question.

This is not to say the end result is unprofessional or chaotic; it simply speaks to the practicalities of independent production at a scale such as theirs, in which success lies in maintaining as small a production footprint as possible.

What the film lacks in technical flourish, it makes up for in an energetic mix of musical tracks that convey an idiosyncratic “cool-kid” character. Beginning with “New Year’s Kiss”, a downbeat indie pop number by Casiotone For The Painfully Alone, MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY’s soundtrack incorporates a variety of under-the-radar pop songs and electro beats to underscore Micah and Jo’s offbeat romance. In the aggregate, the musical sound is decidedly “hipster”— that is, a distinct cooler-than-thou attitude that lies at the convergence between tastemaking anticipation and esoteric indulgence.

A more mainstream-minded (if reductive) approach might have leaned into hip-hop and R&B tracks to signal the protagonists’ racial identity, but a gifted storyteller such as Jenkins realizes the metatextual opportunity in “counterprogramming” his music. His usage of a musical milieu characterized by a predominantly-white fanbase of privileged, creativity-minded college kids & young adults becomes a metaphor for the overwhelming gentrification of San Francisco and the co-opting of working-class aesthetics.

To place two Black protagonists into this environment is to reinforce the friction they feel against it— they stand out because they don’t quite fit. Their inherent incongruity makes true assimilation impossible, and makes their attempts all the more contrived and deleterious. The more they try to blend in with their surroundings, the more they lose their unique character.

This approach extends beyond the music, to the narrative thematic of the film as a whole. The spectre of gentrification looms large over Jenkins’ story, becoming a conduit through which he can explore the tribulations of the contemporary Black experience in America. A centerpiece sequence sees Micah and Jo briefly cede center stage to listen in on a community meeting, rendered in an observational, documentary-style manner. Jenkins uses real people, not actors, simply letting them vent their frustrations about ballooning rents and the existential trauma of being pushed out of their own community.

As the seat of power for the Big Tech giants that wield so much influence over our daily lives, San Francisco’s housing market has become artificially and unsustainably inflated by a perversion of the supply & demand fundamentals. The absurdly-high market valuation of companies like Facebook and Twitter have created a new kind of Gold Rush for the twenty-first century, attracting an endless stream of very-well-compensated workers who subsequently pay top-dollar for the precious commodity that is the city’s housing stock.

Slowly but surely, authentic & colorful neighborhoods like the Castro, the Mission District, or Haight-Ashbury are replaced by a homogenous populace and the artifacts of a lifestyle of conspicuous consumption. These powerful market forces, then, become oppressive to members of the minority or the working-class; an insidious ecosystem that privileges the elite few while dispassionately dismissing those who can’t succeed within it as “not ambitious enough”.

In making MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY, however, Jenkins doesn’t set out to burn down the system; he’s more interested in fostering our empathy for those who are slipping through the cracks. Rather than use his art to shame or alienate the majority, Jenkins’ compulsions as an inclusive filmmaker instead invites them to pull the scales from their eyes— to bear witness to the fact that capitalism is ultimately zero-sum game, and there is always someone who has to have lost something (or everything) for every economic gain.

The unconventional nature of the film’s central love story further establishes Jenkins’s emphasis on empathy. Though their initial connection is driven by (drunken) amorousness, the cold light of sobriety reveals them to be ultimately incompatible. They’re barely friends, let alone lovers. MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY, then, becomes a portrait of two lonely souls struggling to empathize with each other; to find the kernel of connection that they can build a relationship upon.

That it ultimately isn’t there doesn’t mean they haven’t touched each other on an emotional level; indeed, they each come away with a fresh perspective on the complicated nature of the city they call home. The profound empathy that distinguishes the film prevents Jenkins’ voice from becoming too angry about the story’s political preoccupations; it’s less of a condemnation than it is a pointed critique— a compassionate confrontation that’s ready to ask hard questions and, perhaps more importantly, is ready to listen.

MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY was released at arguably the apex of the mumblecore wave, during the brief window of time where a homegrown feature with no stars could secure a coveted screening slot at prestigious festivals like South By Southwest and Toronto. After playing in both, Jenkins’ feature-length debut was acquired and released by IFC. Though it was (and still is) criminally unwatched at a mainstream level, it nonetheless made a splash among indie enthusiasts proactive enough to read its many positive reviews.

The traction wasn’t enough to immediately launch Jenkins into a high-profile directing career, but the film’s quiet strengths would translate to a decent number of fervent admirers (this particular writer being among them). Some of them would be in high places, in a position to help him climb the precarious ladder towards higher scales of production.

For Jenkins, however, this particular ladder would be 8 years tall— he was about to enter a kind of limbo period, marked by scattered output but increased entrenchment within esteemed film circles. By the time he was ready to make his follow-up, he would be in a much stronger position to realize his vision, his convictions reinforced by the fortitude of life experience.

SHORT FILMS (2009-2012)

The story of director Barry Jenkins’ rise from shoestring indie darling to Oscar winner is nothing short of remarkable. At a surface level, the narrative would seem that Jenkins earned himself a modest breakout on the festival circuit with 2008’s MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY, only to fall into silence for eight long years.

When he re-emerged with MOONLIGHT, 2016’s Best Picture recipient at the Academy Awards, it was clear that he had made a quantum leap forward in resources, skill, and talent— all without the benefit of intervening work that built him up little by little. The actual story of what happened during this overlong sabbatical from feature filmmaking is one that many other breakout directors know all too well… although theirs tended to end a little differently.

Jenkins certainly didn’t spend the better part of a decade sitting around idly, waiting for his next big chance. He was active and engaged, albeit in a less visible capacity as a writer. He wrote several scripts for various studios, including an apparent epic about Stevie Wonder and time travel for Focus Features, and an adaptation of Bill Clegg’s memoir PORTRAIT OF THE ADDICT AS A YOUNG MAN.

He also adapted James Baldwin’s novel IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK, which would ultimately become his follow-up to MOONLIGHT many years later. At one point, he was even staffed as a writer on HBO’s hit television show, THE LEFTOVERS, although he’s quick to admit he “didn’t get to do much”.

Indeed, maybe the most interesting paid gigs that Jenkins took on during this time had nothing to do with film at all. Working as a carpenter, Jenkins could apply his exquisite sense of craftsmanship towards something more physical and lasting than cinema. Being from a Catholic background, I find this personally interesting for its parallels to Jesus’ work in the same occupation, especially when juxtaposed against the sentiment of a critic on Twitter (I wish I could remember who) who wrote something along that lines that Jenkins’ camera feels like “God looking with unconditional love upon his flawed creations”.

The throughline here is compassion, and it is a fundamental component of Jenkins’ artistry, sustaining him through the darkest patches of his journey.

Thankfully, the medium of short-form cinema always remained an option to express himself with a camera, and Jenkins indulged in the opportunity several times during this period. From 2009-2012, the production of several short films would find Jenkins developing and exploring his voice, honing in on a set of core, animating themes like racial identity, gentrification, and of course, compassion.

The films that would spring forth from this period collectively demonstrate an insatiable creative curiosity and an eagerness to grow and experiment with different aesthetic styles.

A YOUNG COUPLE (2009)

The first short from this period, A YOUNG COUPLE, closely resembles MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY in its lo-fi portrait of a twentysomething urban couple in San Francisco. The piece, filmed over two hours on a day in late January of 2009, is presented as something of a birthday gift for a “Katrina”— likely a onetime romantic partner given the short’s subject matter.

Shot by MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY’s cinematographer James Laxton on fuzzy digital video matted to the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, A YOUNG COUPLE combines documentary techniques with impressionistic compositions; Jenkins, sitting just out of frame, asks the couple various questions about their relationship, while the couple themselves are seen via window reflections, observational static shots, and unconventional closeups that emphasize the landscape of their facial features in a manner reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s PERSONA (1966).

The implied elegance of a plodding jazz track and a string composition is juxtaposed against the rough visual presentation, which slathers a heavy sepia coating over images that struggles to resolve focus— an unfortunate shortcoming of some consumer video cameras from the era. Jenkins’ own artistic preoccupations arise rather naturally, from his choosing of a subject couple from San Francisco’s creative class to his adoption of a storytelling template that allows him to organically probe for points of empathetic connection to his own life and experience.

Jenkins seems content to have consigned the piece to the graveyard of early internet video, hosting it on his personal Vimeo account in a somewhat “unlisted” privacy designation. One wouldn’t find it by accessing his page alone, but the piece can be seen as an embedded video on the website Director’s Library.

TALL ENOUGH (2009)

In the wake of YouTube’s creation and the sudden popularity of internet video, corporations sought to capitalize on its perceived potential as a potent marketing tool beyond the constraints of conventional, televised commercials; something more organic and creative. This fusion of short film and advertisement would come to be known as “branded content”, and it would become a regular forum for filmmakers to indulge in creative pursuits while getting paid for it.

In 2009, the department chain Bloomingdale’s launched a prescient initiative, recruiting five emerging filmmakers to create fashion-adjacent shorts— one of whom would be chosen by audiences to attend the Independent Spirit Awards. Jenkins’ contribution, TALL ENOUGH, plays like a better-budgeted riff on A YOUNG COUPLE in its portrait of a mixed-race urban couple.

Produced through his ad company Strike Anywhere and lensed by cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra on digital video in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, Jenkins once again utilizes documentary-style testimonials from his subject couple— this time against a blank, white cyc as backdrop. The tone of these testimonials is somewhat off… almost as if they were scripted. These are not actors, however, and it seems that their on-screen musings are a combination of authentic testimony and specific prompts from Jenkins for dramatic effect.

The handheld camerawork, which seems to wander in search of something for its shallow focus plane to latch on to, speaks to Jenkins’ uniquely sensual brand of filmmaking. He seems to use his filmmaking as an opportunity to answer the question of how one can convey the tactility of touch in a primarily visual medium.

TALL ENOUGH focuses on the act of touching itself, conjuring up closeups of hands covering eyes, or drifting across the length of an arm. He uses visual representations of texture — creamy skin, soft fabric, etc. — as a means to evoke a sense memory response from his audience, the restless camerawork moving in parallel to our own roving gaze during private, stolen moments with our romantic companions. Combined with its vignettes of the couple juxtaposed against the buzz of city life, TALL ENOUGH lays the foundation for the visceral sense of visual intimacy that would come to define Jenkins’ artistic character.

FUTURESTATES: REMIGRATION (2011)

Easily the high mark of Jenkins’ extended short-form period, REMIGRATION sees Jenkins at his most visually imaginative, spinning a futuristic San Francisco out of extremely limited resources while deploying the trappings of science fiction in service to urgent socio-political matters. The nineteen minute piece, part of a larger video project by ITVS called FUTURESTATES, imagines a future in which the wealthy elite denizens of San Francisco have triumphed in a war of gentrification, having pushed out all of the blue collar working population.

Russel Hornsby and Paola Mendoza play Kaya and Helen, an interracial married couple living out in the country with their young daughter Naomi, who has a significant but undefined health issue. Their yearnings to return to the city they once called home are given the possibility of real hope when a pair of agents from San Francisco’s upstart Remigration Program show up at his doorstep with a fateful proposition: relocate back as participants in an experimental pilot program that would house them while they work to support and maintain the complicated infrastructure of a hyper-globalized — and hyper-rich — metropolis.

REMIGRATION finds Jenkins working for the first time with an actor of some renown: Rick Yune, who played memorable antagonistic roles in both THE FAST AND THE FURIOUS (2001) and DIE ANOTHER DAY (2002), displays an underutilized charisma that makes an argument for more leading roles in the future.

As Remigration agent Jonathan Park, Yune’s quietly authoritative performance anchors Jenkins’ resourceful visuals with a sense of weight and gravitas. James Laxton returns as cinematographer, crafting a 2.35:1 digital image slathered in a saffron color cast. Lens flares continually invade our line of sight, creating the sensation of a future that’s a little too bright to look at directly.

Elliptical editing complements naturalistic camera work, which combines handheld setups with formalistic dolly moves. Composer Keegan Dewitt, a mainstay in the wave of homegrown “mumblecore” indies that dominated the decade and who has since carved out a formidable career for himself in high-profile films and prestige TV, creates a spare, elegiac score out of subdued strings and piano chords.

Two distinct elements place REMIGRATION as a kind of transitory work for Jenkins, caught midway between the scrappy microbudget filmmaker of MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY and the assured, well-funded voice of MOONLIGHT. Like one of the former’s most memorable sequences, REMIGRATION employs a documentary approach for a centerpiece scene, whip-panning and rack-focusing between various working-class subjects being interviewed about their own desires to return to their beloved San Francisco.

Jenkins interweaves this seamlessly with his narrative by placing similar testimonials from Kaya and Helen, and in the process, conveys REMIGRATION’s most resonant conceit: the socio-economic issue that drives the story isn’t happening in some fantastical future, it’s actually happening right now. Conversely, Jenkins frequently places his characters in the center of the frame, looking directly into the lens as they deliver dialogue. This creates an inclusive sensation, drawing the audience more directly into the narrative— a technique that would grow into a visual hallmark of Jenkins’ later work.

REMIGRATION provides ample space for Jenkins’ other pet themes, such as gentrification, class conflict and male vulnerability, each of which acquire additional resonance via the application of genre (horror and science fiction are particularly adept at communicating our collective anxieties). Jenkins’ narrative provides a compelling setup— so much so that it feels almost like a wasted opportunity to leave it in the realm of short-form. Indeed, there seems to be a tremendous amount of unrealized potential in the premise; here’s hoping that Jenkins is compelled one day to revisit the story in a feature context.

CLOROPHYL (2011)

Of all Jenkins’ work from this period, his 2011 short CLOROPHYL might be the dark horse contender for his most consequential piece. One can see shades of MOONLIGHT in its impressionistic, yet grounded compositions and its dreamy Miami setting. Shot on high definition video by cinematographer David Bornfriend — likely on a compact DSLR setup — CLOROPHYL is a short narrative piece commissioned by Borsch, an outfit founded by Jenkins’ fellow FSU alumnus Andrew Havia. After the release of MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY, Havia tracked Jenkins down to create a spiritual sequel of sorts, set in their shared hometown of Miami.

More than anything, CLOROPHYL stands as a low-key but profoundly resonant example of regionalism— an artistic movementI hadn’t known about until recently, but always sensed an ill-defined but personal connection to. Regionalism, as defined by Havia himself, promotes an authentic depiction of setting by placing the story in the broader socio-political narrative of its environment, combined with the familiarity that only comes from inhabiting said place for a significant period of time.

The story roughs a sketch of a young Latina (played by Ana Laura Treviño) living a somewhat dislocated existence in her own city. She lives in a blandly upscale condominium tower built atop the rubble of a former low-income neighborhood— a kind of “non-place” that promotes a dreamy detachment. Apart from a somnambulant gathering with her indistinctive but similarly-well-off friends, her social interactions are detached, occurring over phone calls and across a crowded bar as she spots the man she thought was her lover out with another woman.

The piece takes its name from a framing device divulged in a Spanish voiceover, using the natural life cycle of plant life as a metaphor for constant change. Indeed, “change” is the core idea at play here, with Jenkins and company examining the sociological ramifications of Miami’s runaway gentrification.

The searching focus that characterizes Jenkins’ camera roams over glitzy new high rises and entire sections of the city that hadn’t existed at all only a few years prior. Returning to his hometown after several years in California, Jenkins is able to portray Miami with the familiarity of a native while simultaneously expressing the alien nature of its growth in his absence.

The sensation lends itself to dreamlike imagery, finding the woman riding a scooter down broad, empty avenues lined with glamorous high rises or ensconced within a curtain of milky polarized glass that turns swaying palm trees into a kind of abstract landscape. All the while, he looks upon these disaffected characters with compassion, not pity… feeling for their sense of isolation in a rapidly-anonymizing and homogenizing urban environment.

KING’S GYM (2012)

Clocking in at a scant three minutes, KING’S GYM (2012) is a compact, wordless vignette about aspiring boxers training at a local Bay Area gym. Set to the elegiac piano chords of composer Paul Cantelon’s theme from the Julian Schnabel film THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY (2007), Jenkins’ searching, handheld camera snatches the poetry in the mundane, juxtaposing a variety of men perfecting their technique and honing their bodies, all while surrounded by dead heroes emblazoned on the flyers from title fights of yesteryear that paper the walls.

A more cynical filmmaker might have titled this piece BEAUTIFUL MEATHEADS, but Jenkins nevertheless finds compassion and empathy in his portraiture of men who are nothing like him— a mild-mannered, bespectacled intellectual in a cozy sweater.

The piece was shot on a digital cinema camera, and it shows— each shot is polished and inherently cinematic, capturing the industrial gym’s yellowed walls with a tactile beauty. The shallow focus plane searches for (and finds) little moments of visual poetry, which Cantelon’s pre-existing cue certainly amplifies. Slight as it may be, KING’S GYM nevertheless spins a different take on a well-worn image in the cinematic medium, underscoring the humanity inherent in ambition, aspiration, and discipline.

Despite accumulating significant momentum, even receiving a United States Artists Fellowship Grant in 2012 , Jenkins apparently couldn’t help feeling that he was spinning his wheels. His 37th year was fast approaching, his forties looming even larger on the horizon. Every year he let pass without a new feature-length endeavor was a deeply-felt loss; entire days, weeks and months were dragged down by the conviction that he’d never make another movie again. Scaled-back ambitions of a career in television writing and commercial directing sustained him through the roughest patches. But here’s the funny thing about genuine people with superlative talents: the less discouraged they may become about themselves, the more others tend to believe in them— and the more readily they stand to move mountains to see them realize their potential.

MOONLIGHT (2016)

It’s rare that the winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture is actually awarded to a film that truly merits the honor. Just as we look to box office dominance as a major (if mistaken) barometer of a film’s quality, the desire to declare a definitive “winner” is so deeply-rooted in the competitive nature of American cinema that we easily forget the Best Picture award is meant to honor the craft of producing— not whether a film is the objective “best”. This is why mismatches between the Best Picture winner and the Best Director winner occur with such frequency. The nuance of the category has been lost —or, perhaps, intentionally ignored — over the years, along with the perception of prestige it promises to bear. It’s not uncommon to completely forget which film was selected on a given year, sometimes not even twelve months on from its win.

The circumstances of MOONLIGHT’s win at the 2017 Academy Awards have ensured that its shocking victory won’t soon be forgotten. Critics immediately hailed director Barry Jenkins’ long-delayed follow up to MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY (2008) as an important work and one of the very finest releases of 2016, but its bid for Oscar consideration faced stiff competition from Damien Chazelle’s lavish throwback musical, LA LA LAND— the kind of richly-budgeted, affectionate ode to Old Hollywood so often showered with praise by Academy voters. As Oscar night unfolded, the narrative of LA LA LAND’s inevitable win seemed all but written in stone,, culminating in Chazelle’s win for Best Director. When Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty took the stage to announce LA LA LAND as the recipient of the Best Picture prize, the night was over… until suddenly, it wasn’t. I had read an article earlier in the day about the statistical impossibility of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the professional services firm tasked with tabulating the voting results and delivering them to presenters, accidentally announcing the wrong winner; the memory of the article had briefly crossed my mind as Dunaway and Beatty opened the envelope, so when LA LA LAND producer Jordan Horowitz interrupted the victory speech to announce that there had been a massive mistake and that MOONLIGHT was the actual winner, it was like slipping into an alternate timeline.

MOONLIGHT’s Oscar surprise was, in every sense of the word, historic. Even without the eleventh-hour plot twist, its inclusion into what is supposedly a canon of special films to be cherished through the generations would be groundbreaking on the merits of being the first Best Picture winner to feature an all-black cast and LGBTQ subject matter. As influential independent films often do, MOONLIGHT seemed to come out of nowhere— a crackling lightning bolt that formed in the blink of an eye to strike at the core of the zeitgeist. The reality was far less dramatic, encompassing a thirteen year slog wherein the material was steadily developed and reworked while its creators’ jockeyed their respective careers into better position. MOONLIGHT began life as an unpublished stage play by Miami-based playwright Tarrell Alvin McCraney, written in 2003 as an expression of his personal struggles in the wake of his mother’s death from AIDS, only to be thrown into the proverbial drawer for the subsequent decade. Titled “In Moonlight, Black Boys Look Blue”, the play eventually caught the attention of the Miami-based arts collective Borscht, who commissioned the creation of Jenkins’ short film CLOROPHYL in 2011.

Independently, Jenkins had been searching for material from which to craft his sophomore feature, growing increasingly despondent as the years passed with no long-form project to show for it. The extent of any development towards this end consisted of a few prompts & prods buried in his Gchat log with Adele Romanski, a producer he knew from back in his FSU days and who had married James Laxton, his regular cinematographer. His eventual collaboration with Borscht on CLOROPHYL, then, would prove surprisingly consequential: it was during production of that film that Jenkins was introduced to McCraney’s unpublished play and immediately recognized a profound personal connection to the material. Though Jenkins couldn’t fully identify with McCraney’s dramatic meditation on the compounded perils of growing up gay and Black, this fellow son of Miami nevertheless could sympathize with the struggle to recognize and assert one’s identity in an inhospitable environment. It was from this perspective as an ally that Jenkins adapted McCraney’s play into a film script during a trip to Brussels.

Jenkins’ success on the festival circuit with MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY had provided him with a prestigious gig judging and moderating Q&A’s for films selected to screen at the Telluride Film Festival, where he would find himself in 2013 as the moderator fielding questions for director Steve McQueen following a screening of his eventual Best Picture winner, 12 YEARS A SLAVE. That film had been produced by Brad Pitt’s production company Plan B Entertainment, who had also met with Jenkins following MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY’s release. In casual conversation following that Q&A, Plan B head Dede Gardner and other executives asked what Jenkins had been working on recently; little did they know he was about to pitch them their next Oscar winner for Best Picture.

While we can’t know how exactly Jenkins pitched MOONLIGHT without talking to the man directly, it’s a safe bet that a key factor in both Plan B’s coming aboard so quickly and distributor A24’s decision to finance and actively produce for the first time lay in the deeply humanistic perspective that Jenkins and McCraney bring to the story of a young Black man in Miami coming to terms with his sexuality over a span of fifteen years. Both McCraney’s stage play and Jenkins’ subsequent screenplay fragment the narrative into three distinct parts that confer a different name on the protagonist as a means to separate his most formative phases: his childhood (Little), adolescence (Chiron), and adulthood (Black). Where source material and adaptation diverge, however, is in their presentation: McCraney’s play called for the three chapters to unfold concurrently, ostensibly to create the perception of three distinct characters only to ultimately reveal that they are the same person. Jenkins would choose a traditional — but no less effective — route, presenting them separately in chronological order. Far from a simplistic choice, Jenkins reportedly drew inspiration from a similar structure found in Hsiao-Hsien Hou’s “Three Times” (2005), using the opportunity of a fragmented narrative and the necessity of casting three very different actors portraying a single protagonist at various ages to convey how one’s environment can induce actual, physical change in response. This narrative idea is easily MOONLIGHT’s most subtle on an intellectual level, but it carries a visceral subconscious message about the larger forces that shape our identities in ways far beyond our control.

The first fragment introduces us to a small boy affectionately nicknamed Little, played by Alex R. Hibbert as a quiet, wide-eyed latchkey kid whose sexuality hasn’t even come into the equation yet, and yet he’s already being antagonized by his peers for a perceived “otherness”. He’s not like the other boys; it’s obvious in “the way he walks”— an observation made by Noamie Harris’ Paula, the self-loathing mother to Little, to Mahershala Ali’s Juan, the neighborhood drug dealer who feels an unexpected compassion for the little man. Harris, Ali, and recording artist Janelle Monaé are easily the biggest names in MOONLIGHT, leaving tremendous impressions despite scant screen time (Ali only appears in the first chapter, and Harris squeezed her entire performance into three shooting days). In playing a character whose helpless addiction to crack causes her to spiral from a respectable occupation in nursing to a lifetime of debasing herself in pursuit of diminishing highs, Harris was reportedly reluctant to even take on a role that trafficked so heavily in ubiquitous stereotypes. However, upon learning that both McCraney and Jenkins’ take on Paula was informed by his experience with his own mother, she was able to channel a three-dimensional pathos that invites our pity and our scorn in equal measure. Ali would go on to become the first actor of Muslim faith to win the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance as Juan, drawing out the inherent humanity in a character that lesser films would reduce to caricature or stock archetypes. Juan, an African-Cuban immigrant trying his hand at the American Dream, becomes an unexpected father figure to Little just as Paula’s effectiveness as a parent starts to unravel.

Monaé’s Teresa, live-in partner to Juan, subsequently becomes a warm substitute to Paula’s growing hostilities. She follows Little where Juan can’t — into MOONLIGHT’s second fragment, which documents a formative episode from the boy’s gangly teenage years. Not so little anymore, he’s dropped the childhood nickname in favor of his given one, Chiron. Monaé, with her otherworldly grace and warm elegance, strikes a stark contrast to the dumpster fire that is Paula, pinned down at the rock bottom of her addiction. Chiron, played here by Ashton Sanders, finds himself bouncing between these opposing maternal forces while trying to figure out what it really means to embrace his masculinity (and by extension, the realization that he’s attracted to other men). The centerpiece scene in this fragment (and arguably the entire film) is a moonlit encounter between Chiron and Kevin (Jharrel Jerome), wherein both boys surrender their performative masculinity to their true feelings; a brief acknowledgment of each other’s humanity before their guard must come back up at daybreak, and the cycle of casual cruelties begins anew.

The third fragment picks up some years later in Atlanta, where Chiron is making a decent — if illegitimate — living as a drug dealer. As played by Trevante Rhodes, this Chiron is unrecognizable from his previous two iterations, having bulked up to an intimidating physicality while obscuring his charming smile behind a chunky gold grill. He goes by the name of Black now, a nickname affectionately given to him by Kevin in Part 2 that is now the last remaining vestige of the boy he used to be. Jenkins structures this third act as a double reunion, with Black being lured back to Miami by an unexpected phone call from Kevin, now an ex-con working as a cook at a quiet neighborhood diner. Along the way, he visits Paula at her rehabilitation clinic to seek an uneasy peace. André Holland delivers a memorably inviting performance as the adult Kevin, who has mellowed out after his time in prison and wishes to reconnect with Black after their moonlit rendezvous all those years ago. Black hasn’t touched anyone — let alone another man — since, having subsumed any sense of an inner sexual life in favor of a caricature of the person he thinks the world wants him to be. In finally reconnecting with Kevin, Black realizes the truth that his environment had worked so hard all his life to obscure: that he is a person worthy of love, and that true self-realization means embracing vulnerability rather than rejecting it.

MOONLIGHT’s unique aesthetic endeavors to construct a visual representation of a “beautiful nightmare”, a phrase used by Jenkins to describe Miami’s particular combination of sun-dappled lushness and outsized class disparity. Working once again with his regular cinematographer James Laxton, Jenkins uses an economic, yet stylish, approach to show audiences a different side of Miami. Far from MIAMI VICE’s glittering cityscapes or SCARFACE’s opulent neoclassical mansions, Jenkins’ Miami sees a canopy of palm trees hang over the pastel housing projects of Liberty Square, the rough-and-tumble neighborhood where Jenkins grew up. Despite going so far as to even include members of the local population as cast members, Jenkins deliberately avoids the “documentary” approach undertaken by so many contemporary indie dramas. Instead, he and Laxton adopt a classical, romantic approach more in line with Wong Kar-Wai’s gorgeous portraits of heartache and longing. Framing in the anamorphic 2.35:1 aspect ratio, the filmmakers soften the crisp lines rendered by the 2K Arri Alexa XT Plus sensor with vintage Hawk and Angenieux lenses. The 35mm and 65mm primes would emerge as their preferred focal lengths, creating a dreamy, romantic bokeh wherein the background dissolves into an impressionistic, circular smear.

Laxton further works towards Jenkins’ vision with a considered approach to light, color, and movement. There’s a diffuse, white quality to MOONLIGHT’s daylight, rendering a buttery palette of color without being too overly saturated. Befitting a locale that’s usually soaked in sunlight, Laxton opts to expose the image with a high contrast ratio, oftentimes illuminating his subjects with a single source of light and no fill. In the color correction suite, Jenkins and Laxton further manipulated their 2K digital intermediate by adding a blue tinge to their blacks, while giving each story fragment its own subtle look meant to emulate the chromatic qualities of different film stocks. Little’s segment endeavors to replicate Fuji’s distinctive rendering of skin tones, while Chiron’s emphasizes cyan colors in a manner reminiscent of an old German stock manufactured by Afga. If Black’s segment seems more vivid than the preceding two, it’s because it draws inspiration from a modified Kodak stock that adds an exaggerated “pop” to color. Laxton’ s camerawork imbues an organic fluidity into Jenkins’ storytelling with handheld and Steadicam movements in select moments, such as an opening shot that tracks Juan’s pathway around the neighborhood as he makes the rounds to his dealers on the block, inadvertently crossing paths with Little for the first time.

Jenkins pairs MOONLIGHT’s dreamy cinematography with a gorgeous, thematically-rich score from composer Nicholas Britell, who follows his director’s attempts to bridge the divide between the “arthouse” picture and “hood” sub genres by fusing an orchestral score with the rhythms and traditions of hip-hop. He begins with a central theme arranged for strings, which is intensely melancholic and suffused with pathos. While perceptibly simple in melody, the piece is highly flexible; Britell can complicate it with added orchestral elements as the story demands, or he can deconstruct it by breaking apart its various elements and processing them into samples or loops. This practice is referred to as “chopped & screwed” by southern hip-hop artists, and Jenkins and Britell employ it throughout MOONLIGHT to evoke the inner conflict that roils Chiron’s beautiful soul. Often sounding like an orchestra tuning up or breaking down entirely, Britell constructs the musical equivalent of chasing an elusive inner harmony. He even samples sound effects from prior scenes, like the soft “clap” of a handshake between Chiron and Kevin, subsequently processing it and transforming it into a percussive or rhythmic element. The overall approach is one of building outwards from the starting point of character, reflected even in an eclectic mix of needle drops that range from classical compositions to vintage R&B, hip-hop and trap— all of which work to evoke a sort of “sense memory” on the part of Chiron; in other words, music as another part of the environment making a physical impact on our protagonist.

With his three features to date, Jenkins’ primary artistic interest in Black identity is made plainly evident, but his overpowering sense of empathy & compassion separates him from similarly-minded directors. MOONLIGHT follows MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY in exploring identity through the lens of sexuality and masculinity. McCraney’s source material stages Chiron’s search for self against the backdrop of the “hood” culture so prevalent in low-income and impoverished communities, fueled by a compelling observation: in such communities, where power and privilege are in short supply and patriarchal ideals inform the bedrock of social structure, men tend to emphasize their masculinity in exaggerated manners as a way of asserting more power for themselves. This adds another layer of conflict atop Chiron’s struggles, creating an oppressive environment that’s almost sentient in its attempts to suppress a noncomforming identity. It’s also what allows Jenkins, a straight man, to successfully make that empathic leap and convincingly depict Chiron’s emerging homosexuality. Indeed, the larger prism of humanity — more so than sexuality — informs his storytelling. MOONLIGHT’s Miami is Jenkins’ Miami; these are his people. By finding his own personal connection to the material on a broader scale, he’s able to encourage a wider audience to do the same without resorting to maudlin sentiments or cheap ploys for sympathy.

Jenkins’ human-scale depiction of Miami, like MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY’s San Francisco before it, speaks to his fundamental interest in regionalism. Jenkins’ ability to render a vivid, tactile sense of place stems from the same well of humanistic compassion that fuels his exploration of Black identity. Rather than shoot recognizable landmarks or lean into the cliches of the local culture, Jenkins stages MOONLIGHT in locations that mean something to him, like the aforementioned Liberty Square housing projects where he grew up. In his commentary track for the film, Jenkins ruminates on the very real possibility that the buildings they shot in may very well have been demolished— the latest victim of gentrification and the radical reshaping of urban environments as playgrounds for the affluent. In this context, MOONLIGHT takes on added depth by capturing a vanishing Miami, rooted in small details that illustrate the socioeconomic fabric of the city as woven by its working class. Specific images linger in the mind, like Little taking refuge from his pint-sized tormentors in the crumbling ruins of a deserted tenement building; Chiron aimlessly riding a tram in a loop around town because it doesn’t cost anything; a security guard breaking up a vicious schoolyard fight, his mere presence evidencing the normalized hostility of an entire student body. It’s now something of a cliché to claim a story’s setting is a character unto itself, but MOONLIGHT can actually make that claim with a straight face— like a sentient person, Jenkins’ Miami physically acts upon our protagonists, prompting emotional and physiological response in a manner that advances the narrative.

MOONLIGHT’s success on the festival and awards circuit is well documented, initially premiering at Telluride before going on at the Toronto, New York, and BFI London film festivals. After its historic Oscar wins (which, out of 8 total nominations, also included a golden statue for Jenkins in the Best Adapted Screenplay category), the film entered wide release in cinemas, earning a worldwide gross of $65 million against a budget that fluctuates between $1.5 and $4 million depending on who’s talking. Now several years removed from its tumultuous Oscar night victory, MOONLIGHT’s worthiness of the honor has only solidified, and is well on its way to becoming regarded as a timeless classic. Often cited as one of the best films of a still-nascent 21st century, Jenkins’ sophomore feature evidences a filmmaker rapidly blossoming into his prime. Indeed, the leap from a scrappy low-budget debut to a splashy, awards-showered masterpiece hasn’t been seen on this steep of an arc since Michael Cimino, but one can reasonably expect that Jenkins won’t follow in the same ruinous footsteps as the vainglorious director of THE DEER HUNTER (1978). He’s simply too humble, too compassionate; his films aren’t a self-aggrandizing attempt at bolstering his own glory, they are genuine attempts at highlighting the beauty of our imperfect and impermanent humanity.

DEAR WHITE PEOPLE: CHAPTER V (2017)

The reviews section on any given IMDB page is a great platform for people to unwittingly tell on themselves. If we truly live in an age of unprecedented media illiteracy, then the vindictive one-star reviews that litter the website might just be Exhibit A. Everyone’s entitled to their own tastes, but like a vengeful Yelp review, the scorched-earth (and often typo-ridden) remarks on IMDB tend to say more about these anonymous armchair critics than the actual work itself. Take Netflix’s DEAR WHITE PEOPLE, a television adaptation of Justin Simien’s celebrated 2014 indie film of the same name. An outspoken, irreverent, and supremely stylish exploration of contemporary Black identity and racial politics, DEAR WHITE PEOPLE positions itself from the outset as an instigator for passionate debate.

A one-star review for CHAPTER V, an episode written by story editor Chuck Hayward and Jaclyn Moore, betrays either the anonymous author’s total inability to process nuance or an unwillingness to truly engage with the issue. “Every single white character… is either a full on evil racist or a complete idiot who means well but still acts like a total racist… I don’t know anyone who actually used the word “woke” and I’m glad I don’t… Netflix has gone full SJW in the past few months. They deserve to lose business over this terrible content”. As self-aggrandizing as it might have been to hit that “publish” button, these knee-jerk surface level criticisms only serve to prove DEAR WHITE PEOPLE’s point— it’s impossible to have an actual conversation when one party isn’t actually listening.

Such reviews also show why artists like director Barry Jenkins are so necessary these days. We need filmmakers to extend empathy where audiences won’t; to keep hammering home the idea that there are actual people on either side of the argument… even when one side is definitively in the wrong. Jenkins understands that changing hearts and minds is only accomplished through dialogue and conversation, and listening is as necessary as speaking. This isn’t to say that dyed-in-the-wool racists and malignant ideologues should be given a platform for their bad-faith vitriol. Rather, for those whose hearts might still be changed, their inherent humanity has to be addressed so as to not foster the persecution complex that reinforces and inflames their opinions.

Set at the fictional Winchester University, ostensibly an affluent Ivy League college, DEAR WHITE PEOPLE follows a group of students actively working to further the conversation on race with white classmates rendered clueless by their privilege. CHAPTER V centers on Marque Richardson’s Reggie, a character carried over from Simien’s feature, who aspires to success as an app developer and an activist for social change. His natural charisma is complicated by the palpable presence of smug self-righteousness, shared by compatriots in the cause like Logan Browning’s Samantha White, a college radio host with piercing eyes devoid of pigment. Most of the episode finds Reggie and his crew gliding through campus, espousing the state of contemporary racial politics to anyone and everyone who will listen (and to those who won’t). Safely ensconced in this liberal arts bubble, they experience the opposite of their intended effect, encountering constant resistance that views them as annoying at best, and insufferable at worst. That all changes during a pivotal moment at a house party, where Reggie gets in an argument with a white classmate about his insistence on using the N-word while singing along to a hip-hop song. A physical fight breaks out and campus security is called, and Reggie experiences the visceral terror of having a gun pulled on him by an overly-aggressive (and unexpectedly-armed) officer who regards him as the sole threat. Reggie leaves the party physically intact but emotionally broken, rendered shattered and speechless by his demoralizing brush with police brutality and racial profiling.

Jenkins’ first stint directing for television finds him foregoing his evocative visual aesthetic in favor of the “house style” cooked up by Simien— a common practice for the medium so as to maintain continuity across episodes. The style of DEAR WHITE PEOPLE’s digital cinematography (fashioned in CHAPTER V by director of photography Jeffrey Waldron) is clean and bright, favoring warm light and naturalistic earth tones. A shallow depth of field and headroom-heavy compositions inject some creative exaggeration into an otherwise-naturalistic approach. Other aspects, like a sequence where the characters break the fourth wall to proselytize to the viewer or even the percussion-heavy jazz score by Kris Bowers, lend a loose, casual air that allows the story to deftly elude the grasp of audiences who think they’re a step or two ahead of the storytellers.

As evidenced by CHAPTER V’s beginning with a James Baldwin quote and ending with Michael Kiwanuka’s single “Love & Hate”, DEAR WHITE PEOPLE is animated throughout by its ruminations on the particular complexities of the modern Black experience. It’s not hard to see why Jenkins agreed to direct this episode, despite the absence of an opportunity to put his own artistic stamp on the material. While the story allows for Jenkins to display a natural aptitude for humor that his feature narratives don’t otherwise provide, the primary emotional vessel on display is outrage— several generations removed from the passage of the Civil Rights Act, there’s a palpable sense that these characters can’t believe they still have to put up with this shit. Look no further than recent efforts to overturn hard-won voting rights, deliberately engineered to disenfranchise communities of color and suppress their vote; the battles thought to be already won fifty years ago are still being fought.

DEAR WHITE PEOPLE, especially as seen in CHAPTER V, walks a very fine dramatic line in fashioning itself as a satire; it must show that the outrage is justifiable enough to wield it as one’s entire identity while also critiquing the more-militant aspects of their persuasion campaign. Indeed, Jenkins’ particular grasp of empathy and its many nuances and complications makes for a rich deconstruction of the so-called “social justice warrior” decried by the aforementioned one-star IMDB review. CHAPTER V’s satirical focus lies not in the usual antipathies of intolerance, but on a particularly acute delusion fostered by the election of Barack Obama to the presidency: that we had entered a beautiful new post-racial era where the ascent of the first African-American to the Oval Office was somehow enough to heal the wounds of slavery and white supremacy. This delusion, sustained primarily by privileged whites in the wake of Obama’s election, was so quickly embraced because it absolved the believer of individual responsibility while “affirming” their (misguided) convictions in their own tolerance. Jordan Peele’s GET OUT, released the same year as this episode, illustrates this conceit rather brilliantly, with Bradley Whitford’s character proudly declaring to Daniel Kaluuya that he would’ve voted for Obama “a third time if (he) could”.

Though any delusions that Obama’s presidency somehow “fixed racism” have been shattered in the xenophobic wake of his successor’s “Make America Great Again” cult, their very emergence still leaves a thorny legacy that must be tangled with. Through the narrative framework of CHAPTER V, Jenkins makes his own attempt to wrestle with the matter, showing how the outrage these protagonists cultivate as their identity has a self-defeating effect: it makes their ability to foster genuine connection even harder, while leaving them shockingly vulnerable to the myriad injustices that dominate our newsfeeds. CHAPTER V in particular presents a spectrum of injustice that members of the Black community might encounter on any given day, be it the exhausting indignity of being pulled into yet another debate about how and when it’s acceptable for a white person to use the “N” word (answer: never), or the very serious matter of suddenly finding oneself on the business end of a weapon wielded by an aggressive authority figure with a twitchy trigger finger. The latter illustrates the life-or-death stakes of our continued inability to communicate; a seemingly-insurmountable bias built into the very DNA of American institutions that justifies the urgent calls for change while deflating any pretense that we’ve made serious progress towards this supposed “postracial” society.

Jenkins uses the central event of CHAPTER V — the argument over whether a white character can justifiably use the “N” word in the context of the lyrics to a hip-hop song — to illustrate how these delusions of equality can be just as debilitating as open hostility. Reggie’s sparring partner is a privileged white kid who presents as friendly and cognizant of racial politics, but nonetheless is quick to defend his alarmingly-casual (and repeated) use of the “N” word as a gesture of respect to the song’s “artistic intent”. He’s fully aware of the word’s history and corrosive effect, but his distorted perception of equality has him convinced that he’s doing the artist a favor by not censoring the work. What he’s really doing is wielding his misguided sense of victimhood as a cudgel, deferring to his ego instead of making the genuine attempt to listen to Reggie’s reasonable concerns. Indeed, the righteousness of victimhood is what allows some to rail against “cancel culture” without reflecting on their supposed misdeeds. They decry the Social Justice Warrior as its own brand of elitism, possessed by a “holier than thou” attitude that empowers the activist as judge, jury, and executioner. The phrase “when you’re used to privilege, equality feels like oppression” has been rather ubiquitous among online circles in recent years, and it feels particularly applicable in this context— reducing the efforts of progressivism to the “woke mob” allows the offending party to indulge in this persecution complex, and conveniently forget that this is all about accountability and speaking truth to power.

Jenkins’ approach benefits from the serialized television format, with the lack of a clear resolution enabling him to avoid any impressions of conclusive “preachiness”. He presents the situation in such a way as to concede the humanity of both parties without resorting to harmful “both sides” equivocations, and then simply leaves the audience to pick up the pieces and figure out where they stand. Though his artistic signature may be subdued, Jenkins’ first stint in television represents real growth into new storytelling formats and aesthetic tones, while setting the stage for forthcoming, major works like THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD.

IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK (2018)

The mid-budget adult drama is all but extinct in contemporary Hollywood, relegated to the realm of streaming platforms after having been squeezed out of theaters by bloated franchise spectacles. In the vanishingly rare instance that such a film does make it to cinema screens, there’s usually an angle, and oftentimes, a cynical one— a naked bid for awards prestige, for instance, or a celebrity’s self-aggrandizing passion project… or both. The existence of IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK — a thoughtful, earnest period romance colored by a sociopolitical urgency — is nothing if not a miracle. Directed by Barry Jenkins from a screenplay he began writing as far back as 2013, IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK is lavishly mounted on a scale rarely accorded to other films of its type. The additional resources empower a filmmaker who continues to blossom into one of the most important artists of his generation, uniquely-positioned to counter the creeping cynicism of our age with a boundless compassion.

Adapted from acclaimed author James Baldwin’s 1974 novel of the same name, IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK treads familiar dramatic territory with fresh kicks; that is to say, that Jenkins’ singularly compassionate and curious worldview serves to invigorate a well-worn narrative archetype— the social-issues melodrama. Under Jenkins’ steady hand, Baldwin’s literary exploration of a young expecting couple separated by the glass plate of a prison’s visiting room is given a higher calling than the cynical pursuits of award season. Set against the evocative backdrop of Harlem in the 1970’s, IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK tells the story of Tish Rivers and Alonzo “Fonny” Hunt, a young black couple who don’t so much fall in love as they plunge into it, quickly conceiving a child as they begin to forge a future for themselves. Said future is complicated by the squabbling between members of their respective families as well as Fonny’s incarceration following an accusation of rape from a woman that lives across town. A title card at the film’s opening explains Baldwin’s decision to name his Harlem story after a prominent Black neighborhood in New Orleans— one he describes as loud, busy, and stuffed to the brim with the type of intimate dramas seen here, effectively stitching Tish and Fonny’s trial of love into the greater fabric of our shared human experience.

Jenkins’ newfound prestige empowers him to assemble a compelling cast of black performers that give resonant breath to Baldwin’s words. KiKi Layne and Stephan James headline the film as our aforementioned couple, delivering a pair of nuanced and effective performances that quickly draw us to their side. Their youth, beauty, and tactile chemistry work together to effortlessly evoke the intoxicating sensation of falling in love, while the hardened performances delivered by their supporting cast members reflect the sociopolitical headwinds continually battering against them. Of these, Jenkins lavishes the most attention on Regina King, who plays Tish’s mother, Sharon. At turns both warm and resolute, Sharon is a fiercely protective matriarch who will go to any lengths for her family— even as far as Puerto Rico, in a bid to track down Fonny’s accuser in hiding and convince her to retract her claims. Colman Domingo delivers a memorable performance as Sharon’s husband, Joseph— an easygoing, amenable man who works overtime to smooth over the inter-family conflicts between the Rivers and the Hunts by partnering with Fonny’s father to steal clothes and sell them so as to help provide for their gestating grandson. Their particular arc serves to reinforce how, in a marginalized community where the system only works to keep its members down, sometimes the system must be subverted entirely if progress is to be achieved.

Jenkins employs an interesting tactic in filling out IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK’s minor roles, casting highly recognizable faces whose screen times stand in direct inverse proportion to their industry profile. Finn Wittrock, perhaps most distinguished by his performance in Adam McKay’s THE BIG SHORT, plays Hayward, the Rivers’ lawyer and an ally who exhibits genuine concern over their wellbeing. Dave Franco and Diego Luna also display a large degree of empathy towards the central couple, Franco being an open-minded and sensitive Jewish landlord who leases them raw warehouse space for them to build their home within, and Luna being a cheerful and generous waiter at their local Mexican restaurant. Pedro Pascal, well-known for his turns on television shows like THE MANDALORIAN and GAME OF THRONES, appears briefly in King’s Puerto Rico sequence as a protective and enigmatic family member of Fonny’s accuser.