Everyone is quite familiar with the famous Rashomon Effect and those who are not, the term refers to the real world situations in which there are versions and testimonies of various eye-witnesses.

These eye-witnesses can be in your head what is described in the actual movie is what happens to us every single day.

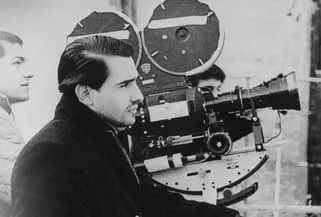

Directed by Akira Kurosawa and released in 1950, Rashomon has won numerous international awards and introducing the world to the Japanese film scene.

Kurosawa was forty years old when he made this movie and was at the initial stages of his career which was to last for five decades giving some greatly produced movies to be ever made in the Japanese film industry. And also to leave a lasting impression on film production. Rashomon surfaced at that time of his career journey when he left Toho for some time where the studio was located which was to be the home of his many more films to come.

Apart from being incredibly directed, Rashomon became renowned for grasping the difficulties which humans come across regarding experiences and memory.

The plot of the movie is focused on a grove where an accident took place. A dead body of a samurai is found who was stabbed to death by a woodcutter. With reference to this crime a bandit is captured but the twist lies in the fact that his testament in court as well as those of the samurai’s wife and the woodcutter who came across the samurai’s body all happen to present outspokenly different realities or versions of the truth.

The various perspectives are portrayed in the movie but the most vivid and clear concept is that the stories happen to be self-serving. The bandit’s narrative shows him as a braver and a bolder character as compared to the other accounts.

The woodcutter on the other hand, leaves out a very significant detail which could have raised fingers at him and get him into jeopardy. Whereas the samurai’s wife is either a very helpless victim or rather a scheming and sinister woman.

The viewer is left in speculation though and may be even those who are telling the stories and not too sure what the truth actually is which will make them face the reality.

During the years from 1949 to 1951 Kurosawa made movies for Shintono, Shochiku and Daiei. Albeit Daiei was somewhat hesitant and showed reluctance to fund Rashomon because he was of the view that the movie was quite unconventional and exceptional from the traditional movies that are generally made. According to Daiei, the film was quite eccentric and will be difficult for the audiences to understand.

All of those fears doubts and proved to be groundless when Rashomon became one of the most worthwhile and profitable films of 1950. Daiei’s view that the film is unconventional was not all wrong, it was and even quite deep-seated in design as well and all of these added into its originality and aided in making it go sky high with international cinema at such a time when art cinema was surfacing with very strong and powerful potency on the film circuit.

With immense averseness, the film was allowed to be submitted for an overseas festival competition. Rashomon won the first prize in the prestigious 1951 Venice Film Festival. It was through Rashomon that world got to know about the expertise and talents of Kurosawa as well as the assets of Japanese cinema.

Rashomon Effect is not only about the variations in the perspective but is occurs specifically where these differences arise combined with the lack of evidence to heighten or disqualify any version of the truth including the social pressure for the closure of such situation.

Want to watch more short films by legendary filmmakers?

Our collection has short films by Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, the Coen Brothers, Chris Nolan, Tim Burton, Steven Spielberg & more.

Rashomon Effect: Kurosawa’s Other Films

Similar to a number of movies by Akira Kurosawa, Rashomon is two-story based film and set during a time period when the society was going through a social crisis. And in this instance, Japan’s 11th century period is revealed which is chosen by Kurosawa to shed light on the farthest points and extremities of the human behaviour.

As the film is opened, the screen shows three characters who are seeking shelter from a raging rainstorm underneath the ruined gate of Rashomon. This gate is used to guard the southern entrance of the imperial capital city of Kyoto.

As this group waits for the storm to pass, the priest (Minoru Chiaki), the commoner (Kichijiro Ueda) and the woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) dicuss a scandalous crime of a noblewoman (Machiko Kyo) who was raped in the forest and her husband the dead Samurai, (Masayuki Mori) was killed by someone or himself and a thief Tajomaru (Toshiro Mifune) who was arrested in this regard.

Rashomon Effect on the World

Rashomon has surpassed its own status as a film and effected the culture at large too. It symbolized the general notions about the truth and the unreliability of memory. The Rashomon Effect is usually spoken of in the legal industry by judges and lawyers when the first hand witnesses come up with conflicting testimony.

Kurosawa came to rank amongst the leading international figures of cinema with Rashomon and following movies by him. It was more than just a commercial entertainment film. It had ideas of a serious artist possessing aesthetic design.

The modernist narrative not only impressed the audience making it a classic but the massive visual skill and power which was brought to the screen with amazing shots of forest, the sun directly. It was incredibly a sensual film. Nobody has ever filmed forest like this.

The film was a conscious attempt to recreate and recover the marvel of silent filmmaking. The cinematography by the Kazuo and editing are marvellous. Many sequences of the film were purely silent in which the imagery seems to speak and carries the action.

One such sequence which was the best in the series of moving camera shots was of following of the woodcutter in the forest before he happens to find the evidence of the crime.

The brilliant designs of Kurosawa’s films which are motivated with precision makes him a great filmmaker. Like the rest of his outstanding films, Kurosawa responds and reacts to his world as a moralist as well as an artist.

Japan was devastated after the Second World War and that is why Kurosawa’s embarked on a journey with immense artistic ambition as well as moral urgency to make a series of films. Seeking via his art, to produce a legacy of hope and faith for a ruined nation.

The desire for restoration which these stories clearly exemplified had to deal with a struggle with an entirely opposite and dark too. Rooted in the cynical and distrustful reflections of human nature, Kurosawa’s films tend to have a tragic dimension.

With the aid of the common human propensity to cheat and to lie, he manifested a tale in which the ego, disloyalty and conceit of the characters make the search of truth such a tough thing to find making it too difficult. The question arises that whose account is to be believed? Whose testimony of the crime is to be relied on? Who is correct? It is a question which one cannot seem to find the answer to as all versions of the truths are distorted in such ways that only benefit their narrators.

The world faces a dark moment as the ego takes over everything. Portraying a quite dark scenario, at the last moment with utter simplicity and beauty, Kurosawa pulls back from the darkness he exposed. The woodcutter makes the decision of adopting the abandoned baby and as he walks away with the child in his arms, the rainstorm lifts.

No matter what one decides regarding the conclusion of Rashomon, it is as genuine and real as it comes making it truly a classic. The greatness that emanates from this movie is both undeniable and palpable.

The nonlinear narrative and the sensual style which formed this film and in turn reformed the face of cinema is outstanding because to expect this from someone who was still a young filmmaker is astonishing.

Transcription: Kurosawa and Rashomon Kurosawa’s Rashomon is a particularly dramatic example of a film that understands itself to have the kind of claim on its audience that the greatest art has always imagined itself to have on its audience. So I want to begin by talking very briefly about what I call the moment of Rashomon. There’s a bit of confusion or at least historical, chronological confusion, or inconsistency in the notion that in the in the principle that we end the course with a film that was made and shown internationally before the sum of the last two films that we’ve seen in our course. But my reasons for that, as I partly explained in an earlier lecture had to do with the fact with my desire to show a certain continuity amongst forms of European cinema, and the link between genre Anwar and the Italian Neo realists, and the French nouvelle vog is so intimate, that it seemed to me important to show you that progression in sequence. But if we had been going by strict chronological order, we would have introduced this Kurosawa film a bit earlier, because it was made in 1950. And, and in 1951, it won an important International Prize of the Golden Lion, the highest prize available at the Venice Film Festival in 1951. And this had a seismic effect on internet on movies around the world. The dramatic and powerful subject matter of Kurosawa’s film, of course, riveted attention. But even more than that, the the freedom and imaginative energy of his stylistic innovations in the film had a profound impact on on filmmakers around the world. And the the when the film was shown in at Venice in 1951. What another affected had been one of the prize was to introduce Japanese cinema to a wider world. It was the first significant Japanese film, Kurosawa, the first important Japanese director to gain reputation a reputation outside of Japan itself. In fact, there are many film buffs, and especially specialists in Japanese film, who are somewhat resentful of Kurosawa’s eminence, even though no one denies that he is an eminent director. Because there are other directors, the two I’ve listed under item two in our in our outline are the most dramatic examples, Mizoguchi and also who are often thought to be his superior, even greater directors than Curacao. This is a debate forth. This is a debate of nuances. All three of these directors are major artists. But But it is true, I think. And it is widely recognized that Kurosawa was the director who, who crossed that barrier more, more immediately, at more dramatically than any other and open the world, not just to Japanese cinema in some degree, but opened the world in some longer sense to Asian cinema more generally, that the so called Western world, the European and an American cinema universes, had been fairly oblivious to Asian cinema and certainly to Japanese cinema. Prior to this, and the appearance of Rashomon, its enormous impact in 1951, began to change that. So that was demonstrated in part in that moment in when when Rashomon won this award, won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival was a reinforcement of a principle I’ve been discussing throughout the semester, the notion of film as an international medium, the idea that the notion that that directors from different national cinemas were now being deeply influenced by directors from from other nations. And that and that film itself was in some deep way, a global phenomenon, this even even an international form. And, and this, I think it was in the 50s and early 60s that this idea began to become more and more widely embraced by film goers in the United States and in Europe, but perhaps especially in the United States. And one mark of this of this, of this the emergence of cinema as a as a fully recognized independent art form. Obviously, people had thought this and many directors had achieved artistic distinction before this, but I’m Talking about sort of the public understanding of movies, the way people in different cultures actually recognized implausible thought about movies. It was as if this is the moment in which movies were understood to enter the museum in a certain way to earn in public in a public sense, the status that that more traditional art forms had had. And one of the explanations for why this would have been so why it would have had such a powerful impact. I think I mentioned last time that this insight was partial in the United States, especially That is to say, in the 50s and early 60s, it began to dawn on movie critics and scholars and of whom there were only a few at that time and and then movie audiences that European films and Asian films, especially Japanese films, might have great artistic value. But it was it was a longer time before Americans began to realize that their own native forms of films had had a similar kind of authority. And so this moment, in the in the early 1950s, was a deeply significant one. Let’s remember, historically, what it represented in in in Europe and in the United States. It’s the moment of the emergence of Italian neorealism, which itself begins to establish a kind of very powerful claim on people’s on people’s attention. Oh, one irony of Rashomon success was that it was not very successful in Japan, when it was released in 1950. And the producers, the production company responsible for the film was very dubious about entering it in the competition, didn’t think it was a significant film. But even though it transformed Kurosawa’s career, because of the immense recognition, it finally got, and corsola himself recognized, he’d been making films for almost a decade before that, but Rashomon was his most ambitious film to that point. And it also incorporated more innovative strategy, visual strategies than any he had tried before. established him as an international director, and I mentioned the names of two other directors, just as a from different traditions as a way of reminding you of, of another feature of this phenomenon. Another reason, as I began to say earlier, for why this moment was such a significant one. And the term I use here is modernism modernist cinema. Remember, one of the ways to understand this idea is to recognize that a great revolution in the arts had occurred at the turn of the 20th century, the end of the 19th. And at the turn of the 20th century, and we’ve talked about this earlier, it’s the movement we call modernism, right? It’s the moment of Picasso, it’s the moment of James Joyce. And it was a kind of revolution in both art, visual art, literature, music, took place in this period, and and what was characteristic, among the characteristics of this modernist movement was a new was it was a newly complicated and self conscious attitude toward narrative itself towards storytelling. So it was a modernism in literature and ignored, involved, among other things are kind of a continent, if not a hostility, at least a kind of a kind of, or antagonism, at least the kind of skepticism about inherited traditional categories and ways of doing things. One form this took a narrative was to decide what to dislocate or disorient the narrative line, instead of telling a story in a chronicle chronological sequence, a lot of the great works of fiction of the modern of the modernist era of books, books by writers like Joseph Conrad, or or Proust, the great French novelist who was so preoccupied by memory and human subjectivity, or the great German novelist, Tomas, mon, number of other great figures that we could mention began to construct stories in which in which chronological order was profoundly disrupted. And they also began to connect, create stories in which there were multiple narrators, in which and the effect of multiple narrators begins. Even in even if you do nothing more than have multiple narrators, you begin to raise questions about the about the veracity, the truthfulness of the of any single perspective. And you will understand when you look at Rashomon why this movie embodies the many of these same modernist principles. But the point is that cinema as a as a as a narrative form, lag behind these more traditional arts. And it really wasn’t until the 1950s. And partly because of films like Rashomon, that it began to be recognized that the movies too, could embrace and embody the principles of modernism. So one way to understand what happened in the 1950s was, was to right now is to is to recognize that directors like Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman, the great Swedish director, and Fellini, the great Italian director of the the inheritor and a expander of the Neo realist tradition going far beyond a narrow realism, that directors like that began to create films that in a in a formal sense in a structural sense, in and also in terms of their content had the kind of complexity nuance and skepticism, that and even the philosophic of self awareness that would that was characteristic of high modernism at the turn of the 20th century. So it’s as if what was going on was the movies themselves, were now asserting themselves as a modernist art, right? I don’t mean as a contemporary art, right, I’m referring specifically to the modernist movement and to the end to the end to the dislocated, and, and, and, and much more demanding kinds of narrative strategies that are characteristic of the modernist movement. So Rashomon played a fundamental role in this sort of transformation of what we might call the cultural understanding of movies among ordinary people, as well as among scholars, critics and other filmmakers. I want to mention one other point, give you a kind of note, to clarify, from some of what I’ve been implying, what what I want some of what I implied when I talked about Mizoguchi and Mizoguchi and Ozu as directors who are often more even more highly regarded than Kurosawa. I’ll leave that to each individual film goer. All three directors are astonishing and remarkable. But it wouldn’t it be appropriate to talk even about this single film Rashomon, without paying respects to those two great directors whose dates I’ve put on your on your outline. I won’t talk about individual films by these directors, but I urge you all to look them up in in read about them in David Cook’s history of narrative film, and think about experimenting by extending your knowledge of Japanese cinema by trying films by these two remarkable directors. One of the things that’s characteristic of all three of these directors of Kurosawa, even more fully of Mizoguchi, and ozone, ozone most fundamentally of all, is that their films are marked by a kind of impulse towards stylization, toward fabulous, feeble like creations, that distinguish them in some ways from Western from European and American films. And I think that one reason one explanation for this has to do with the long, longer artistic traditions of Japanese society. Japanese film grows out of theatrical traditions like kabuki theater, or no drama, and drama, both of which have profoundly stylized and fable like qualities. They’re anti narrative, in some sense, and any of you who have ever had even minimal experience with either of these two theatrical traditions will understand what I’m what I’m discussing that these are theatres of gesture, and up and up, and have very decisive sort of symbolic representation. They are what we would think of as sort of realistic characters, or realistic stories are, are not a part of these very ancient traditions, these theatrical traditions go back hundreds, even 1000s of years. So there’s a there’s a tradition in Japan of a kind of stylized, of symbolic representation. And, and you’ll, you’ll see, I think, how of how, in Russia, how powerful this principle operate, how powerfully this principle operates in Rashomon, what even when the film even when film itself emerged in Japan in the silent era, when emerged in a slightly different way. And one of the most interesting features of the silent film tradition in in Japan was the appearance of a character who has no counterpart in western cinema, a character called a Benji bns, a char, any of you heard of it? None. What he was essentially was a narrator and explainer, and he stood next to the movies in a way and gave explanations right, he said, Now, we will introduce the villain now we will introduce the you know, he was like a kind of intermediary, a narrator, or, or a concierge Who, who, who mediated between the audience and the text who gave the audience information. Again, it’s a deeply in one sense, we might think of it as a as a as an anti narrative tradition as a tradition in which things are presented or spoken rather than literally acted out or, and certainly one in which in which, in which the details of a story are less important than its than its general, then its general outline. So when we talk about stylization, one of the things we’re talking about is an impulse toward what we might think of as generalized argument instead of a specific argument, and an impulse to have one moment stand symbolically for many other moments. And what we might think As a simplification, or a, or a distillation of reality, into certain symbolic moments that are that are thought to be emblematic in certain ways, but don’t necessarily have a realistic feel. And you’ll see almost instantly when this film begins, I mean, there’s a there’s a kind of prologue. And then when the film makes a transition into the first sequence that takes place in the forest, you’ll begin to see what I mean when I say that the film seems to enter into a kind of symbolic realm in which you’re in which your sense of reality is, in some sense of undermined, as if you’re entering into a dream or a symbolic space. Kurosawa, talking about that astonishing sequence at the beginning of Rashomon said that the the cameras, complex movements and the movements of the of the character himself, everything is in motion in that remarkable opening sequence. Some people have called it the most visually poetic sequence in the history of movies, what you call our call, this moment, a moment in which the camera was shown to be penetrating where the into a space where the heart loses its way, as if you’re penetrating into a, into an ancestral space, into a, into a space of space that’s dreamlike, in fundamental ways. So that very opening of the film istat were almost very opening of the film establishes this kind of complexity, this kind of I don’t want to exactly call it an ambiguity, but this, this, this complexity, about the about the nature of the reality that you’re watching, and this is even before the film proceeds to to present, essentially four different accounts of the same event, these four different accounts conflicting with each other in a variety of ways. So these, these abstracting, or symbolizing, or stylizing narrative of add dramatic traditions lie behind and shape the movies in Japan, even movies like Kurosawa’s, which embrace the cameras freedom in a way that’s much more characteristic of Western directors than of then of Eastern ones. Although the the the second of the two directors I’ve listed on your on your outline is especially famous for holding his camera almost stationary for tremendously long time for and in fact, he sometimes he is sometimes called he sometimes called a director who tries to create a Zen aesthetic, because the camera is so quiet and so stationary. And so in relatively inactive, it’s a it’s a style that lays tremendous emphasis on the nuances of facial expression and, and vocal tone. So that and both Mizoguchi and those who do, in some sense, have an even greater sense of stylization in many of their films than then Kurosawa does. But I don’t want to oversimplify because they are also capable of very great realistic moments. And they have a moral realism that’s at least as powerful in their films as Kurosawa himself. Of course, I was career is a very remarkable one. And and I wish I had time to talk about it in detail. Organizational Structure of Japanese cinema was not unlike the structures that developed in in Western societies in the United States or in France, there were essentially monopolies of not not a small number, but a relatively larger number of film production companies operating at at different levels of significance. So they were second rate, and there were second level and third level production companies as well. But all of them operated in similar way there was the director was a was a more dominant and major figure in this system. And they surround surrounding each director, what were a group of workers and a group of creative people, including usually performers who went with the director from space to space, from film to film, as well as his technical people that he would often use, they would often use the same people to write the music and the same crew to work on the film that the same if they could succeed, get the same cinematographer. And the Kurosawa’s It was called Kurosawa’s group was called the Kurosawa Gumi, jus EMI means the group or or khadra, the chorus, our group worked with us on a series of film, I don’t mean it was always identical. There were changes, but it was a stable group unified especially by Kurosawa’s vision and, and supervision. And I’ve listed here a few of his most famous and fundamental films besides Rashomon, ikiru maybe his greatest film I really Stick film set in the modern world, the title means to live. And it’s about a man who discovers that he has only a few months to live in it stars. The actor, techie Xu Mora who plays the woodcutter in Russia on the actor, the other actor that you’ll see in in Russia on that, that that is one of Kurosawa’s favorites and appears again and again, Kurosawa’s films, is the act of Toshiro BuffOne in Russia, and he plays the bandit, and you’ll see what a remarkable figure he is, though, so I’ve only listed a few of his films here. But among his most important, Rashomon, ikiru, Seven Samurai, many people would say, the greatest of all Samurai movies, and probably the greatest of all western movies, because it puts most westerns, American westerns to shame. It’s influenced by American westerns, as as Kurosawa himself acknowledged, and it was itself that film and made in 1954, remade as an as an American film some years later, under the title, The Magnificent Seven. And it was so successful that it was then there was a sequel was made something like this Magnificent Seven return. And in fact, one of the deep features of Kurosawa’s work is that many of his films have been remade by other directors, both American and European directors. Rashomon was made 14 years later or remade. 14 years later, with Kurosawa given screenplay credit in a film directed by Martin rich in the United States called the outrage and it really tells the story that’s at the heart of of Kurosawa’s film. It starred Paul Newman, among other things, and Edward G. Robinson, among other significant American actors, Throne of blood I mentioned because many people see it as the most successful of all adaptations of Shakespeare. It’s a Japanese Kabuki eyes version of Macbeth, and many people starring to shiroma funi. And many people think of it as the greatest of all Shakespearean adaptations. Yojimbo is a samurai film a much more straightforward Samurai film in many ways than Seven Samurai, also stars made funi and it has brilliant, brilliant sword fight sequences in it and anticipate the kind of thing that is now common in Asian cinema, but much less trivially done in Kurosawa’s, then many of these later films that merely seem to want to entertain us by their sword play and and the physical grace of their of their actors, but don’t connect nearly so powerfully as cortisol was films due to a profound and serious historical setting and story. Yojimbo was also made into an American movie called Last Man Standing in 1966. I mentioned kagemusha, only because it’s a later film, and it’s many people, many people admire it. Because it shows that Kurosawa was working effectively, even in old age. He made another film in 1985, one of his final films called Ron ra n, which is a remake of King Lear. And these two older films. Later films kagemusha and Ron, show his v show Kurosawa’s visual sense of visual imagination to great effect. But they feel stylized in a way that they weren’t stylized may not be the right word. They feel abstract in a way that earlier, Kurosawa’s films do not. They are extraordinary spectacles, but they don’t have the same interest in character, the same focus on character that his earlier films, despite their stylization, seem to do. I’ve saved my most of my time today to talk about Russia on itself. Because it’s such a central and significant film, and I hope when you when you will watch it, you’ll not be impatient, and you’ll especially that you’ll watch for the ways in which from sequence to sequence, the visual style alters it’s a very, it’s a very demanding film in that sense. Let’s begin by talking a little bit about the problem of rape in cultural stories, because I think that one of the problems with responding fully to Russia man is is that we especially in in, in the in the Western world, are, are newly struggling with notions of of gender identity and, and, and and of the legacy of patriarchy. That gives us a particularly fraught and complex, but put us in a fraught and complex position in relation to stories like that of this film, and I want to be, I want to confront it right in the beginning. As some of you may know, the story of Rashomon is the story of a rape. There are four different A rape occurs at the center of the film. And the and there are four different accounts of what happened of how the rape occurred. And the film is partly a meditation on why would What? What motives do the different tellers have for for putting this particular spin on the story? How, and and part of what’s subtle and disturbing about the movie is that when when the first testimony is given, it’s not fully clear yet to us that we should be skeptical of the testimony. And when I think the first time, I think the first one of the test one of the people whose testimony we heard is the murderer himself, or the or is it the rapist himself, the phony character, he’s the first one to testify. And it’s, as he’s testifying, it begins to dawn on an attentive viewer, that maybe his testimony is self serving in certain ways that there are certain way things he’s saying that maybe we shouldn’t fully accept. And, and then when the next account comes, our sense of skepticism is reinforced, and fortified, we begin to worry about what what and and then the film itself reminds us of the fact that these tales are problematic, because the film structure is so interesting. roughly every 10 minutes or so I’ve timed most of them that are a little less than 10 minutes, in some cases a little longer than some, you’ll have an extended narrative sequence, which will last about 10 minutes. Usually, it’s the testimony of one of the one of the people appearing before the before the court. And then when that after that happens, the the film, the film sort of shifts into or shifts into another mode. And the way you can tell is that it shifts back to the scene with which the film opens with all the way through the scene. It’s marked by this, but the structure of the film is marked by this return to a scene at at Rashomon gate, and which I’ll explain in a moment. So the point of the one point that I’m trying I’m trying to get to here is the idea that as we watch the film, and we begin to sort of weigh the accounts that different people give of this, of this rape, many of us are likely to feel uneasy and different and disturbed, because that one of the things that disturbs me in the film is the woman’s reaction to her rape, she feels terrible shame. It’s as if she had felt, and and there’s an impulse, there seems to be an impulse in the film that certainly some people have certainly gotten there, they at least they perceive an impulse in the film, or an impulse in the narrative to blame the victim. Right? We have to get in some sense, what I’m suggesting is that, not that that response is inappropriate, but that that, that it’s a little bit off key off off center, because if you recall, the idea that the film is deeply stylized, and it’s said in an in an ancestral past in a, in a, in a, in a in a in a in a in a in a medieval Japan, in a moment of terrible social breakdown, in which vestiges or ancestral attitudes towards sexuality and gender are being are being mobilized or awakened. Right. And if we understand that, in that way, we can begin to recognize that our own discomfort with the subject matter is a discomfort that the film itself may even be aware of and may even be encouraging. And I what as you’re watching the film, watch how in some sense it especially in in one moment, where the where the victim of rape makes an appeal to her husband right after there’s a sequence where, where we see her embracing her husband and looking into his face. Now, the problem is she’s giving this testimony. And there’s some reason to, it’s after the fact and there’s some reason to doubt what she’s saying, especially as the film goes on. Nonetheless, it’s a it’s a moment of, of great power, and what what and and that moment at least mobilizes sympathy for the victim of rape that is very significant, because you hear so little of it elsewhere, elsewhere in the film, not that the woman is, is is treated badly or but but she’s subjected to the same suspicions as the other as the other central characters. But there’s a larger thing to think about a larger a larger way, a larger way in which we can accommodate ourselves to the slight discomfort we might feel at turning a story of rape into a philosophic discourse as this film does. And that’s simply here’s how we might do that. Let me just remind you that stories about rape are at the heart of many cultures. How many of you have heard of the story of the rape of Europa? It’s a Greek myth. None of you. In many ways, it’s the story of the foundation of Europe. Zeus, disguised as a white bull is to the great Greek gods, right the God of all gods and one of one of Zeus. His best habits are the most most remarkable habits in the in the, in this in the in these mythological stories is that when he gets a yen for a human female he will disguise himself as a as a creature of the earth and rape her go down and rape her right and he does this with Europa and the story of the rape of Europa is a kind of symbolic story which is which which later, Europeans actually took as a kind of one of the founding tales of how Europe itself was founded. Can you think of another story in which Zeus is a rapist? How about Lita? How many of you know the story of Lita and the swan? About about which gates wrote So, so, such beautiful poems, again, Zeus, the God of gods disguises himself as a great Swan, and swoops down on Lena, this beautiful woman, and rapes her as it were in the, in the guise of the swan, and there’s a brilliant, almost pornographic, really powerful poem by wb Yeats, in which he describes this terrible moment of rape. It’s one of the, it’s one of the great poems of the Western world, and it, it’s about this rape and so that what I’m what I’m reminding you of is that the massage money that you may sense there is a massage money that’s embedded in culture, it’s a massage you need that’s embedded, it’s a massage need that’s embedded in, in all the stories that human beings tell them in many of the stories that human beings tell themselves about, about the world, about the relations of men and women, and often, especially about the foundations of society. So that so that this, so that this meditation, on on human frailty and human deceit focused on a rape it from that perspective is one of many such stories, not a unique object at all. And it seems to me that it’s that that, that that’s one of the ways in which we can recognize that what Kurosawa is doing is part of a more long and complex and in many ways, very disturbing. habit of mind that many, many cultures share the title, Russia among Western people, students are often puzzled by it, it’s a reference to the name of the gate. But the word gate is complicated, too, because it’s not an American gate that just opens and closes. It’s a great, great massive entrance to the city of Kyoto in the southern part of Japan in the late 11th, or early 12th century, it’s a period of complete disillusion and, and, and, and destructive poverty, in political chaos. And the broken down condition of the gate, which you get long shots of, you know, you see this massive structure in, under which it’s a terrible rainstorm going on, under which certain people come to get shelter from the rain. And that is Russia, gate, right. And, and it’s broken down condition symbolizes the broken down condition, of politically and socially of the society represent that is represented there. And again, and again, the characters gathered beneath the gate, to protect themselves from the weather engage in conversation about the about the nature of about human nature, are human beings innately evil, do they always lie can we never trust them. And one of the characters who carries on this discourse is a is a priest, who has a kind, who has an idealizing tendency, which another of the characters a commentary, he’s called the commoner, he’s an ordinary man is constantly mocking and arguing against, it’s almost a kind of argument that reminds me in some ways of the argument between spirit and flesh, in, in Cervantes Don Quixote, in which in which sansho, Pons is constantly reminding the idealizing Quixote of the miserable actuality of the world look, when you get stabbed, you bleed, when you’re, when you haven’t eaten, you’re hungry, right? The world is real in a way that that that ideal, that ideal and miserable in some respects, in a way that idealists don’t like. And so that’s the kind of argument that runs through these interludes as the as the film goes on. So the title refers to the Russia gate and Russia gate is itself a massive symbol for the breakdown of order for the misery of India for the miserable circumstances that individuals find themselves in and what you one of the things you’ll see is that it’s it’s chilly, it’s cold, it’s raining like mad have tremendous torrential downpour, incidentally, created partly by fire trucks. In his autobiography, Kurosawa talks about how difficult it was to create this sense of an immense ongoing almost a tsunami of rain. And he talked about the technical difficulties of of doing so. Very impressive, very impressive rain, the most impressive rainstorm in the history of movies, I think. And so these, these these people are gathered beneath the gate in order to in order To protect themselves and the gates symbolic significance is it is important, we will notice that one of the things they do when they get cold is they go over to certain parts of the of the building, it’s a wooden structure already half broken down and, and, and in decay, and they’ll break off banisters or other pieces of wood and rake them up and turn and burn them up. And the implication is if things go on like this, pretty soon the whole gate will have will have been consumed by people who have tried to take shelter under it. So it’s so it’s a symbol of the breakdown of social order, and of an end of the society. I’ve already mentioned, the medium the name of the Japanese word is Meiko. And I mentioned it here just because I wanted to clarify, I wanted to be sure all of you understood what was going on there, the husband is dead. When the testimony begins. He’s a samurai. So a husband, a samurai who is the husband of the of the rape victim. And as the story unfolds, you’ll see what what you’ll get the basic facts, but you’ll also find that even when the film is over, there are many fundamental things you won’t be able to have decided. And I think that’s part of certainly part of Kurosawa’s point. So the medium is just this this clairvoyant type apparently, characters, real characters believed in and socially recognizable in late middle in late medieval Japan, a character who had claims to have access to the words and beliefs of dead people. So the dead man testifies in another way of reminding you that we’re looking at a very stylized a dream, a story that isn’t in a narrow sense realistic at all. The visual style of the film is especially remarkable, and and astounding, in some ways. It’s almost as if each of the tested, each form of testimony has its own style. And you might want to watch the the way in which Kurosawa sort of builds his eclectic and dynamic since of the eclectic and dynamic way in which in which Kurosawa’s editing camera work use of music combined to create a kind of almost constant visual excitement. One of the most remarkable things about the film is how many sequences in it are without dialogue with extended wordless sequences, truly, entirely cinematic, the opening sequence is almost the opening sequence, the first extended sequence in a forest, which comes after the sort of introduction, which I’ve described earlier, is a magnificently clear example of that process. And in that, one of the things that you may notice, in that sequence especially, is the way in which you become increasingly disoriented about the direction in which the woodcutter is going. He’s apparently narrating the story in his narration sort of segues into a visual experience, as happens again and again in the field. And the visual experience we have shows him going into the woods, walking and then discovering first a woman’s hat, and then discovering other things and discovering a body and then running away in fear. And and as he penetrates into the woods, one of the things that happens is the camera is always moving and and the camera becomes as interested in the in the forest itself in this densely wooded forest and in the play of light and dark. Because the sunlight comes through the wooded canopy in odd and profoundly, visually powerful ways. It’s as if you begin to have a sense that that that the camera is at least as interested in the woods and in the play of sunlight, as it is in the motions of the of the woodcutter and that the whole sequence has a kind of profoundly lyrical, but also in some degree, disorienting sense that as Kurosawa said, you’re entering a space in which you’re you’re you’re entering a space that’s dreamlike, that’s dangerous, a place where the heart will lose its way, right as if you’re you as if you’re entering a symbolic space, not a realistic space, right, a stylized space and in some in some in some deep way. And there are there are a couple of specific strategies that Kurosawa uses in in the in the film to reinforce I think our sense that he is indeed that he’s engaging every element of the of his of his cinematic palette, in order to create his effects. One thing he does violate certain rules that Beth especially at the time, which would have been tremendously shocking to professional directors, one thing he did does in the film, was he points the camera at the sun and he creates sun effects, right? That was a no no, it was a sort of rule that directors should never do that. Of course, it doesn’t. It does and you’ll watch while he does it. It’s very it’s it’s very powerful that it also has As a disorienting effect of the effect of making us understand more deeply what it’s like to work to work our way through this incredible dense forest in which the event occurred in which the crime occurs as if the forest itself is a space. So complex, and so private, so caught off from from the outer world that almost anything could could happen there a space of dream, a space of terror, a space of symbolic fable. And, and there’s, there are a couple of other things I wanted to mention about the way his camera behaves. One is that he, of course, I will use this here a device at certain points in the film that a very interesting device, it’s the official name for it that the fancy name for the technical term for it is, he makes what is called an axial cut a XL, it’s really a form of a jump cut. That is to say in, you know, an abrupt edit, which which you’re not fully prepared for which breaks in it, a jump cut, as you know, breaks the the action in in mid stride or in mid action and then jumps to something else in a kind of in a way, that’s slightly disorienting. that eliminates, right, it’s elliptical, it eliminates, it eliminates connection or transitions, right. And, but, but the axial cut does this in a very dramatic way that also calls attention to the apparatus of the movies. The most dramatic places in which this occurs in the film are certain scenes in which you see the samurai husband tied up sitting on the ground, tied up like this, kneeling on the ground, and the cameras at some distance from him and moves toward him. But it doesn’t move toward him in a smooth tracking motion that is characteristic or tracking motion characteristic of most films, what it does is it moves forward and it stops and then it jumps, it moves forward. And then it and what you feel is leaps forward. And what’s happening, of course is that he stops the cameras forward movement moves, it further makes a cut so that what you want. So the effect is the camera moves, method, the cameras jerky, but it’s it’s, it’s as if it’s, it’s as if it’s a speeded up, in some sense, we can feel that the camera is becoming elliptical. So say this fellow in the front is the person I’m focusing on, I’ll be here that you’ll see this shot, then you’ll make two minutes and then you’ll see this shot and it will. And the effect is very abrupt, and you watch what happens. So one effect at one One consequence of this kind of a shot, is that you watching it, you can feel how mechanical it is you you begin to think to yourself, well how could that have been created, you’re aware of its mechanical qualities, that is to say, you become partly aware of the apparatus behind the making of the movie, it’s a moment of self consciousness that other elements of the film also reinforce. So the visual style is profoundly eclectic and dynamic. I’ve mentioned at the axial cut and pointing the camera at the sun. Maybe I’ll mention one other device that he one of the other technically intricate and and at the time revolutionary thing that Kurosawa did was he violates what’s called the 180 degree rule. And the 180 degree rule essentially has to do with your sense of spatial orientation in it within the frame, right? The essentially the 180 degree rule holds that if you’re showing characters moving in this direction, right? See, you’re showing a character moving this way, you won’t suddenly if he’s still going in the same direction, show him walking this way. Because it disorients the viewer, right? So that if but what is in our film in in Rashomon, there are certain moments and there are hints of it in that opening sequence, or that lyrical first sequence in the forest that I mentioned, in which you in which you can see that the cameras own movements. complicate and in some sense, confuse our sense of where the woodcutter is going. And, and, and it’s in that sequence and some other places in the film as well with 180 degree rule is violated. And the effect again, is to disorient us is to feel, gee, I don’t know whether I’m coming or going this guy doesn’t know whether he’s coming over what kind of space is he in, again, violating certain conventions of traditional filmmaking in order to create new effects. So it’s, and the, the the consequence of these choices, the impact of these choices in 1951, when the film won its prize was profound. I want to say one other thing about another aspect of the film’s structure, which I’ve described perfectly and I apologize for being so Tongue Tied about it, but as I tried to describe earlier, the basic structure of the film becomes fairly clear. What happens is you get testimony. Then there are interruptions in which you as essentially all four of the primary pieces of testimony take place in the past, right. So there, so what we have are flashbacks, but competing flash And that various points, the film returns to our scene of rain at Russia gate in which the people under the gate, the three people under the gate, two of them are actually partial participants. The third, the commoner was just a kind of listener to the story, although a profound commentator on it, right, the Santo ponza type who’s, who says, look, the world is miserable. Why should you? Why should you believe anyone, and the priest is constantly resisting him? Well, when we return to these moments, and it was so so we returned to Russia on gate several times, many times in the film, and every time we returned to that spot, where are we we’re in the present time of the film. So one of the things that film does, it creates what I call a drama of the telling of the story in which the conversation that’s going on in underneath Rashomon gate is a kind of meta commentary on the story that we’re watching, right? The characters inside the film, comment on Well, can we believe her? Is this credible? Why did she say this? Right? And the effect of this meta commentary is to create essentially a separate story. What’s the separate story? It’s a philosophic topic. The topic is the telling of stories. In other words, this interruption creates a new kind of moral and thematic complexity in the film, something that’s characteristic of the great novels, and fiction works. I’d mentioned earlier in our in the lecture that appeared at the turn of the 20th century, what we have not only are the is the principle of unreliable narration being introduced, and the principle of competing flashbacks being introduced, and the principle of dislocated chronology being introduced, all of those things are operative. But what is even more important about it is that this more these moments of conversation amongst this, those three characters, that Rashomon game also constitute a kind of philosophic meditation on the nature of storytelling and the nature of truth. Right? And they actually say, Well, how can you believe a person or what is truth? How can we believe what anybody says? So the so the film calls attention, not only to the profound subjectivity, of human responses, and the profoundly unreliable nature of memory, right, but also the extent to which individuals themselves have reasons developing from their egos, right, to distort and tell stories that are more flattering to themselves, right. And so that by the time we come to the end of the film, it isn’t clear at all, when the film is over, whether there is a truth and whether there is any final truth that we can embrace. The issues are not finally resolved. But what is resolved for us is the idea that human reality is immensely complex, that that human beings are endlessly deceitful, that that the stories they tell about themselves and others may not be trustworthy. So in other words, that the film opens out into a kind of philosophic profundity that’s partly a function of its structure. So it’s another example, one of the most remarkable examples that we’ve seen in our course of what I call organic form of a film whose have a text whose whose structure helps us understand what it’s about, and whose structure is part of what it means whose structure is essential to its meaning. We couldn’t imagine this film as a straightforward chronological sequence, it wouldn’t be it wouldn’t be able to do what it does. This so what i what i mean by the drama of the telling of the story is literally that that is to say, there’s a second story that in a second subject matter in these interlude, let’s call them interludes in these interruptions, in which we return to the present time get out of the path. And those those interludes are an extended, philosophic and moral conversation about human nature, about the nature of the human of our human capacity to understand the world. And, and, and our capacity to talk about it, to narrate it accurately and fully. So this drama of the telling of the story, this drama of the screening, this drama of the making of the story, is as important a dimension of the film as its actual story as the actual story that it wants to tell. I have two other points to make about this remarkable film, and I’ll be done. The first is that one of the things I think you’ll notice, as the story goes on, and as different different people give different accounts of what happened is that the actual physical conflict between the two male characters, which one would expect to be grand and heroic, is almost always clownish and on heroic, we expect this great. He’s a samurai warrior after all, and the man he’s doing battle with is a very famous or infamous, banded, criminal, so gifted a criminal that he has that he’s famous right. And yet in there, and both what what one realizes in retrospect that we When the criminal the tissue to shiroma phony character gives his gives his testimony in the beginning of the, in the early part of the film. He’s exaggerating his own his own martial genius, so that we don’t fully realize that at first, but it becomes clear and clear to us as the film goes on, that he has a motive to sort of exaggerate his heroic stature and his strength and so forth, not to mention a motive to exaggerate and maybe to lie about the woman’s reaction to his to his forced attentions. All of that is, is is a is a central part of of our of our of our understanding of what of what is at this what is at stake, I guess, when when we think about the the subject that Russia among the various subject that Rashomon gestures toward. So it the clownish on heroic behavior of these fighters is something to note because there’s a deep skepticism in the film itself about about all forms of a grand of human aggrandizement, there’s a there’s a skepticism that the film shares with the commoner who said, Who, who maybe is too negative about human nature, who thinks human human beings are completely objective that this is the justification for the most selfish kind of behavior, because no one can behave well. Alright, I have hardly exhausted the film. But I hope I’ve said some things that will be valuable and useful to you on your first viewing. But let me end by talking about the ending. Because the ending of Rashomon presents us with a problem similar to the problem that we confronted in a film like the last laugh during that sermon, in which there seems to be a kind of optimistic or, or reassuring ending. To the to this film, The film has been very dark and rain. And in fact, one of the ways you can tell that the film has changed registers is that the rain finally disappears. Well, as you’re watching the ending, which way which is quite explicit, even heavy handed about its attempt to return us to a sort of more hopeful view of mankind, you should ask yourself, does it deserve to be deleted. All through the 40s when Kurosawa was first learning his trade, he began to direct early in the 40s. And he directed this film in 1950, his his his his first real master work, he’d become more and more confident and ambitious as a director during this period. But he hadn’t sort of displayed his full capacities as a director until this point, most accounts of his career suggest. But during this period, in the 1940s, Kurosawa took upon himself what he regarded as a social project, which was to try to help renovate Japan after the devastation of the war. And his films of the 40s almost always tried to suggest various forms of wit, various ways in which people could behave decently and heroically, if not decent, not heroically, at least decent decently, in an effort to sort of renovate and re reconstitute a damaged society, a broken society, one of the reasons that the that the breakdown of ancient Japan is so powerful in Russia, man, is that no question that is that a corsola. and his and his cast believe that in some sense, there was a symbolic analogy to be made between conditions in Japan, in actual Japan in 19, in the 1940s, and early 50s, and the broken, terrifying conditions of society in the in the 11th and 12th centuries. In the past parable, that narrative is telling us. And so and this film continues that tradition. I think, I think many, many viewers, I among them, have the feeling that, that this is more wish fulfillment on Kurosawa’s part than reality. And one could say, from an artistic standpoint, then one might conclude that it’s a weakness in the film, I think I might say that, that the film might be more powerful, more truthful to itself, that it may, that that the ending, that that the ending that’s tacked on May undermine its deepest energies in disturbing ways. So it’s another example of a way in which commercial and social imperatives may be may be interfering with the artistic integrity of the text. But it’s significant, important to understand that this was a tendency that was present in Kurosawa’s work all the way through the 40s. And that therefore, it’s a kind of expression of of a of a of a Have a moral sense that the director had that that would be that begins to become less powerful after Rashomon. And although although he remains deeply moral director, so the ending is a question and you might want to ask yourself what, how you would react to how you would respond to the question of the relevance of the of the ending to the rest to the rest of the film. Let me end with a reminder about maybe what is, in some ways, the most powerful aspect of what happens when you’re watching Rashomon, I’ve said that you feel that you’ve entered into a kind of, if not a dream, into a kind of uniquely stylized space in which what happens resembles what happens in real life, but is, but but also distills what happens in real life highlights in a way that isn’t true of actuality, right. And I think you’ll feel this, I think you’ll feel this, this mythic tendency, all the way all the way through the film. But it’s in a in a certain in a certain sense. It’s a way one way of capturing what I’m saying is to say that there is a tension in the film between this impulse to be mythic, to tell a story that it understands to have a feeble like significance. And its sense of the complexity and, and concreteness of actuality, one, that is to say, so there’s this wonderful constant tension in the film between the enormous persuasiveness of the individual images that you see. But your sense also that you’re in a world that’s not totally real, that so this is the tension I’m trying to get you to feel you can feel it in the dialogue, you can feel it, but especially you can feel it in the visual images, in the in the visual texture of the film, you can feel a kind of tension between an impulse to mythologize and to stabilize and an impulse to show the world in its in its in its deepest and most concrete elements in its most in its most authentic actuality. And the tension between the two g This is so real. This is so unreal, this is so fable like, it’s part of the secret of the movie. And one way you can feel it within immensely intense power is sometimes when you see the way the film deals with human flesh. There are certain scenes for example, where a woman’s hand will be on a on a man’s body, right? Talk about what you can, how you can be erotic without, without offending anyone. There’s a moment where you can see the woman’s fingers pressing into the man’s flesh, right? It’s an immensely erotic and powerfully concretizing moment, it reminds you of flesh, it reminds you of the film’s power to capture actuality with the vividness that goes far beyond what words can ever do, right? The visual power of movie. And that’s what I mean when I say that there’s this constant tension in the film, in the film between the mythologizing tendencies of the story. And of course, I was imagination, and what we might call the breaking tendency, the the concretizing tendency of the of the, of the film medium, which, which has this growth pack this capacity to register the gross concrete reality of our experiences with a detail and a power that no other medium can, with this sense of tension between a story that wants to be a fable and a story that wants to persuade you of its of its concrete reality is part of what makes the film so memorable. And so and so significant.Spoiler