COMMERCIALS (1963-1965)

In Greek mythology, there was a boy named Icarus who, longing to escape from his island home of Crete, constructed wings from feathers and wax in an attempt to fly away. He was warned to not fly too close to the sun, but—of course—he ignored such warnings. You probably know the rest: Icarus’ magnificent wings melted and he plummeted into the sea, where he drowned.

Film critics like to invoke the myth of Icarus when referring to once-promising directors who fizzle out in short, spectacular fashion. It’s easy to see why—there’s something compelling about watching the public disgrace of a prodigy. It’s reassuring to see the best of us cut down by hubris and excessiveness, if solely for the reminder that they’re only human like the rest of us.

No other director has generated comparisons to the Icarus myth more than Michael Cimino. When his film THE DEER HUNTER (1978)—only his second feature at the time— swept its way to Oscar glory, he was hailed as something of a second coming. Fortunate enough to be working within the auteur era of filmmaking where a director’s voice reigned supreme, Cimino suddenly found himself with the keys to the kingdom.

What happened next is the stuff of cinematic legend—his next feature, 1980’s HEAVEN’S GATE, became the most expensive film of its time, epically flopped at the box office, and nearly bankrupted its parent studio, United Artists. Now the prodigy had become a pariah, and while he would direct a few more films in his lifetime, he would never (at the time of this writing, at least) achieve a respectable level of success again.

The purpose of the Directors Series is to examine the works of great directors and chart their development along their road to success. I also believe it’s equally as valuable to examine the works of promising directors with a very different (downward) career trajectory, if only to see where they went wrong. Sometimes there’s more of a lesson to be learned in failure. Who better to tackle for this type of analysis than Cimino, the granddaddy of cinematic hubris?

Born in 1939 in New York City, a third-generation Italian and son to modestly artistic parents, Cimino’s promise was evident at the very start. After a rough childhood spent as a delinquent, Cimino enrolled in graduate school at Yale University and studied painting, architecture, and art history. While a future working in films wasn’t quite clear on the horizon, his interest in the broader sense of art drew inspiration from the films of John Ford, Luchino Visconti, and Akira Kurosawa.

After college, Cimino was living in Manhattan and working in advertising. He found that he was incredibly gifted in directing commercials, which led to considerable early success. Even then, Cimino’s penchant for obsessive meticulousness and perfectionism was well-known, and often irritated his clients—but in the end, they would always have to admit that the final product was excellent.

Cimino directed commercials for a variety of clients like Eastman Kodak, Kool Cigarettes, and L’Eggs. Unfortunately, the majority of his commercials aren’t publically available to view for the purposes of this article, and it seems that a comprehensive list of his commercial work doesn’t exist. However, there are two commercials available for us to examine– ones which helped to make his name as a director.

UNITED AIRLINES: “TAKE ME ALONG” (1963)

This is the commercial that put Cimino on the map, and is still admired today as one of the best spots ever made. The spot is a cheery, bouncy little number that’s styled like a big-budget Hollywood musical. In “TAKE ME ALONG”, a variety of housewives musically plead with their husbands to take them along on their business trips, a request that United Airlines is more than happy to accommodate with their special deals.

Watching the spot forty years later, it’s difficult not to be reminded of TV’s MAD MEN and the rampant, unacknowledged sexism of the era. The women plead to be taken along with such zeal, you’d think they never get to leave the house. Business travel is portrayed as something like a men’s-only club, something to which the women can only look in on from the outside.

(Assumingly) shot on 16mm film, the look of the spot is purely commercial and a fascinating time capsule for the early 60’s. The jet-set culture was in full swing, travel was a glamorous luxury, and upbeat jingles were still the best way to sell product. Cimino replicates United’s color branding space with generous amounts of blues, red, and whites.

The men are clad in the grey suit uniform of the era, and the women sport bright pastel dresses for a contrasting, somewhat-mod effect. Cimino frames a lot of the action using one-point perspectives, and incorporates a lively mix of dolly shots and rack zooms to create a kinetic energy and complement the choreography.

Some of what would become Cimino’s signature stylistic elements are present here. The elaborate set design and the Americana imagery on display would become staples of Cimino’s work, and it’s clear from even this earliest of jobs that Cimino was fascinated with these preoccupations.

Later on in his career, Cimino would express his interest in helming a big-budget, old-fashioned Hollywood musical called PORGY & BESS. Due to reasons very much apparent in hindsight, “Take Me Along” is arguably the closest that Cimino will ever get to realizing that dream.

PEPSI: “DISNEYLAND” (1965)

Seemingly the only other publicly available commercial work of Cimino’s, this joint collaboration between Pepsi and Disneyland is a curiosity. Produced in 1965, the spot entitled “DISNEYLAND” still retains the relentless, cheery optimism that was the mandate of advertising in the 60’s—however, it also has a gritty, verite edge reminiscent of John Cassavetes’ work. I actually hesitate to say “reminiscent”, as “DISNEYLAND” predates Cassavetes’ first feature FACES by three full years.

The spot is a freewheeling, dizzying take on a romantic date at Disneyland. A young, beautiful couple smiles gleefully as they ride the Matterhorn and Thunder Mountain. A narrator expounds upon the virtues of the so-called “Pepsi Generation”—perhaps one of the earliest examples of catering to the youth market in advertising.

(Assumingly) shot on 16mm film, Cimino’s black and white handheld photography is kinetic and exciting. He utilizes point of view shots to recreate the rush of the rides, and plays fast and loose with continuity, framing and geography. It’s more of a montage of moments than a traditional spot. The cheery jingle accompanying the spot is emblematic of advertising conventions at the time, but Cimino’s visuals give the spot a gritty edge—something Disneyland isn’t necessarily known for.

If anything, the spot indicates that, even at the earliest stage of his career, Cimino had a bold, daring vision that he was confident enough to execute well. While this type of approach would serve him well in his debut film THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT (1974), and exceedingly well in THE DEER HUNTER, time would eventually show that there’s fine line between confidence and indulgence. For Cimino, crossing that line would ultimately be his undoing.

THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT (1974)

By the early 1970’s, director Michael Cimino had already made a name for himself as a helmer of standout television commercials. At the time, Cimino had moved to Los Angeles from his native New York, to pursue a career in movies. As it happened, Cimino’s first major feature came about due to a perfect storm of factors. After the breakout success of Dennis Hopper’s EASY RIDER (1969), road movies had become all the rage.

Cimino’s agent gave him the idea for a road/heist movie, and then partnered with a fellow agent at William Morris Agency to bring the idea to actor Clint Eastwood’s attention, who had earlier expressed interest in producing a road picture of his own.

Eastwood liked Cimino’s script, and intended to direct it himself. However, upon meeting Cimino, he was impressed with the young man’s confidence and relinquished the reigns, giving Cimino his big cinematic break. The final result was 1974’s THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT, a lighthearted buddy movie/heist film that announced his arrival as a new, major talent in Hollywood.

THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT roots its story in the conventional tropes of the classic heist genre, but imbues the countercultural edge of films like EASY RIDER and Monte Hellman’s TWO LANE BLACKTOP (1971). Thunderbolt (Clint Eastwood) is introduced to us as a mild-mannered preacher in a rural Montana town.

Imagine our surprise when, in the middle of his sermon, an armed thug enters the church and tries to kill him. Meanwhile, in another part of town, a young playboy drifter named Lightfoot (Jeff Bridges) steals a car right under the nose of a salesman at the dealership. These two men’s paths collide, and they end up getting along so well that they decide to keep each other company for a while.

When two men from Thunderbolt’s past—his ex crime partners Red Leary (George Kennedy) and Eddie Goody (Geoffrey Lewis)—come back into his life with a debt to settle, he convinces them to join him in one last heist. They decide on an audacious plan—to rob the very same bank they heisted in their last job together. The four men move in together into a small trailer in Warsaw, Montana and take on cover jobs– all the while planning the heist of their lifetimes.

THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT benefits from some truly fantastic performances. While there’s nothing that truly challenges any one actor in terms of their reach or craft, Cimino nonetheless compels them to turn in high quality work. As a hard-edged man with a mysterious past, Eastwood’s Thunderbolt is intriguing and inherently watchable. It’s not too far of a cry from his career-making turn as The Man With No Name in Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns, but since when has Eastwood ever been noted for the diversity of his roles?

Additionally, a fresh-faced Jeff Bridges portrays the dandy-ish Lightfoot as relentlessly energetic and good-natured. He’s the optimistic foil to Eastwood’s grizzled cynic, which creates an endearing friendship dynamic. We get the notion that, had their partnership gone on longer, they might have become the next great crime duo, like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

This is a very male-oriented story, and as such there isn’t much in the way of female supporting performances. George Kennedy, that lovable heavy from Stuart Rosenberg’s COOL HAND LUKE (1967), gives a layered performance as the film’s main antagonist. As a former friend and war buddy of Thunderbolt’s, his Red Leary is a conflicted antagonist motivated mainly by a sense of macho principle—he thinks his buddy burned him, so he wants retribution.

He also makes the most of the surprising number of comedic opportunities afforded to him, and manages to steal almost every scene he’s in.

As more of a side note, a young Gary Busey cameos as Curly, Lightfoot’s co-worker at his landscaping cover job. He’s got the frame of a scrawny kid, but that creepy, bucktoothed stare of his is just as present as it’s always been. Despite only being in one scene, he somehow still gets prominent billing in the film’s opening credits.

One of Cimino’s strong points as a filmmaker has always been his visual eye. His striking compositions and attention to detail have given his films a unique, sumptuously cinematic patina. Working with Director of Photography Frank Stanley, Cimino effortlessly makes the transition from the claustrophobic television screen to the wide vistas of a 2.35:1 35mm film frame. THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT was shot in Montana’s Big Sky Country, and Cimino takes full advantage of the location by using wide angle lenses to capture Montana’s striking mountain vistas in all their glory.

Cimino employs a natural, lifelike color scheme and prefers to frame his compositions wider and more symmetrical than most directors. Each background is distinct and lovingly rendered, from the moldy wood slats of a dingy motel to the snowcapped peaks of distant mountains. His studies in painting and architecture subtly inform images that deal in layers of perspective and an awareness of setting.

The frame is packed with details that enrich the story, yet are unobtrusive. Much of these details create a distinctly American feel—a tone that Cimino would incorporate into his signature style.

Cimino’s camerawork is mostly classical, preferring to tell the story via static and dolly shots. However, more experimental techniques, like rack zooms, handheld takes, and moving point of view shots, point to a knack for innovating within the confines of time-honored cinematic boundaries. For example, Cimino and editor Ferris Webster employ a powerful cross-cutting technique during the heist sequence as a way to build tension and spread the action out.

By going this route, Cimino pays homage to similar cross-cut sequences like the climatic baptism scene in Francis Ford Coppola’s THE GODFATHER(1972), as well as the racetrack heist scenes in Stanley Kubrick’s THE KILLING (1956). Although he references the masters who came before him by adopting this technique, his unique characterization and comedic timing gives the proceedings his individual stamp.

Dee Barton provides an appropriate, if not entirely memorable, musical score. Taking on a decidedly country “honkytonk” tone, it’s rolling, rambling nature is suitable for a lighthearted road film. Cimino also peppers the film with an eclectic mix of prerecorded tracks, starting with an austere church hymnal and going on to cover genres like folk and rock. Given the time period of its release, the musical landscape reads as hip and contemporary, and gives the film a distinctly “good old country boy” flavor.

Out of Cimino’s successful films (which unfortunately only make up a small percentage of his filmography), THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT is curiously underrepresented. It’s a first-class effort that did well upon its release and paved the way for Cimino to make his crowning achievement, THE DEER HUNTER.

Many storytelling devices that would become Cimino’s calling card make their appearance here—his geometrically-minded compositions, a preoccupation with Americana imagery, and the use of spirituality/religion/ritual to inform his characterization. Watching the film for the first time, after having seen some of his later works, I found that Cimino’s skill as a director was immediately apparent in his debut. His career may not be something to emulate, but his visual style most certainly is.

Perhaps it’s appropriate, given how Cimino’s own career has played out, that his films seem to have a subtext of sadness or nostalgia for a time gone by (or, alternatively, a time that never existed). There’s an underlying, subliminal current of loss to THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT that yearns for a more innocent time, when the land was pure and untouched. When cars had the freedom to go off the road and roam the countryside as they saw fit. When a criminal could disappear into a small Western town and remake himself into a model citizen.

It’s not a coincidence that the film’s final moments take place in an anachronistic, one-room country schoolhouse that’s been moved from its original site to a highway rest stop and now serves as a historical sideshow. For Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the times are a-changing—the landscape is changing under their feet and, just like that one-room schoolhouse, they’re quickly becoming relics in a world that no longer has any use for them.

THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT is a striking debut—indeed, it’s one of Cimino’s very best films. I’d venture so far as to even say that it’s worthy of a spine number in the Criterion Collection, especially given its under-appreciation in the years since its release. With all the negativity surrounding his later works, it’s refreshing to go back and remind ourselves why we fell in love with him in the first place.

THE DEER HUNTER (1978)

The annals of film history are dotted with enduring classics that define their time. They act as avatars for the national mood, and are a dreamlike reflection of our collective unconscious. It’s not a coincidence that some of the most potent films ever made came out of the 1970’s, a time of great social unrest and doubt. As the Vietnam War raged halfway across the world, , we experienced a national crisis of conscience– spurred on by the nightly images of violence and death beamed directly into our living rooms.

It was a loss of innocence for America, in that a far-off fight shattered thousands of families, communities, and towns. A countless number of promising futures were tragically cut short in service to a war that we couldn’t necessarily justify getting into. We began to question the moral authority of our leaders and the decisions that were made in the best interests of “democracy”.

It was into this climate of social upheaval that director Michael Cimino released his second feature film, 1978’s THE DEER HUNTER. The film painted a sobering portrait of a small Pennsylvania steel town rocked by loss when three of its sons go off to Vietnam. The war was still something of a taboo subject in cinemas when Cimino made the film, but the man had already become well-known for his bold, confident vision and daring subject matter.

In the context of its time, a three hour film about an unpopular war was a huge roll of the dice, but the gamble paid off in spades– THE DEER HUNTER is a qualified masterpiece, and one of the most emotionally harrowing experiences in cinema. It would go on to secure an Academy Award in Directing for Cimino (as well as Best Picture, among many others), and would undoubtedly become the crowning work of his career.

However, success has a dark side– and the perks of all these accolades would subsequently enable Cimino to indulge in excess. In other words, Cimino’s yellow-brick road was a road to ruin.

THE DEER HUNTER also holds the personal distinction of being one of my favorite films of all time. A number of the story’s themes are ones that I’m drawn to as a filmmaker in my own right. I could expound at length about the film’s subtext and message, because each subsequent viewing of the film (I’m now up to three) reveals new insights.

The story is so layered and dense that it requires multiple viewings– a task made not-so-easy by the film’s ponderous three hour runtime. When I first saw the film, I didn’t particularly respond to it, and it was only upon my second viewing that something clicked. THE DEER HUNTER demands your time and your patience, but it will reward you substantially in return.

The film is splint into three distinctive, hour-long acts that form a framework not unlike the triptych in classic art. Act One takes place in the sleep mountain town of Clairton, Pennsylvania. Michael (Robert De Niro), Steven (John Savage) and Nick (Christopher Walken) are three old friends from childhood, having never left their sleepy community.

They spend their days forging steel and their nights drinking copious amounts of Rolling Rock beer and chasing after the town’s slim selection of women. When the film begins, it is Steven’s wedding day, and these rambunctious boys are intent on getting absolutely shitfaced before the big ceremony. In the town’s community center, a raucous reception is held to not only to send off the groom and his bride in style, but to celebrate Michael, Steven, and Nick as hometown heroes before they depart for Vietnam to serve their country.

One of the biggest complaints against the film is the lengthy reception scene, which is one of the most drawn-out and longest in the film. Initially, the scene seems aimless and bloated– however, this extended sequence sees Cimino planting the seeds of his story in an uncontrived, almost invisible fashion.

The sequence introduces Linda (Meryl Streep) , a beautiful young woman who finds herself the unwitting object of affection between both Michael and Nick. We also meet Steve (John Cazale), one of the few members of the rambunctious boys’ club that finds himself impotently left behind while his more-virile friends go off to glory.

In a way, THE DEER HUNTER’s first act symbolizes a pre-Vietnam America, drunk off its innocence and presumed supremacy as a superpower. This is alluded to in a striking interlude halfway through the party, where a haunted-looking serviceman back from Vietnam disrespects Michael by refusing his drunken attempts to buy him a drink. It’s a ghostly preview of the shocking transformation that lies in store for our three heroes.

The film’s second act shifts abruptly to a startling explosion, deep in the jungles of Vietnam. Michael finds himself in the middle of nightmarish chaos, and then suddenly/impossibly reunited with Nick and Steven. Their reunion is cut short when they’re captured by Viet Cong forces and imprisoned in a claustrophobic water prison along the banks of the river Kwai.

As prisoners of war, they’re forced to engage in emotionally battering games of Russian Roulette for their captors’ entertainment. They escape by riding a piece of driftwood down the river, but are separated by a botched rescue attempt by American forces.

A short while later, Nick is treated for his wounds and released back out into the bustling city of Saigon. Looking for a cathartic release from the POW experience that haunts him, he’s lured into the lucrative world of underground Russian Roulette. Cimino’s second act depicts a harsh awakening to the hellish nature of war, and the lingering scars its causes.

The third act finds Michael returning to Pennsylvania. Clad in an ornately-medaled military uniform, he projects an image of success and honor, but like the spiteful serviceman earlier in the film, he too is haunted by spooks he can never quite shake. He reconnects with Linda, beginning a reluctant affair that’s driven more by comfort and companionship than lust or passion.

His transition back into normal life is a hard one, filled with many stumbling blocks. He reunites with Steven, who has since lost both legs and an arm. Heavy painkiller drugs cause Steven to ramble incoherently and make him a fraction of the man he used to be. Curiously, Steven mentions that money is regularly sent to him from Saigon– from who, he doesn’t know. Michael deduces that it’s Nick, which means that he’s still alive. Invigorated by the realization, Michael heads back to Saigon to save Nick from a devastating fate.

THE DEER HUNTER is full of nuanced, involving performances. Cimino aptly captures the drunken playfulness and nonchalance of his homegrown subjects, which give this very serious film its only moments of levity. When the tone changes, Cimino is equally perceptive at capturing their faded smiles and hardened hearts.

The 1970’s was a great decade for Robert De Niro, which saw him turn in his best performances in some of the greatest films of all time. In THE DEER HUNTER, De Niro embraces a blue collar, flinty mentality– externalized by a scraggly goatee and a trucker cap. Despite his gruff exterior, he’s quiet and sensitive; somewhat distanced from the carousing nature of his friends.

His insightfulness translates into a steely resolve and quick wit under the pressure of Vietnam’s hostile conditions. It’s an Oscar-nominated performance every bit as iconic as TAXI DRIVER’s Travis Bickle or THE GODFATHER PART 2’s Young Vito Corleone.

Christopher Walken won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance as Nick. Nick is initially presented as the group’s jester, but it’s a facade meant to disguise how scared shitless he is about going overseas. In a private, drunken moment early in the film, Nick begs Michael not to leave him behind in Vietnam, no matter what.

This anxiety ultimately breaks him, and his transition from eager and fresh-faced to gaunt and lifeless is captivating to watch. His performance is entirely deserving of the Oscar, and endures as one of cinema’s most haunting figures.

John Savage, who in my opinion is a severely underutilized character actor, also experiences a striking conversion. He’s the picture of virility and swaggering machismo at the beginning of the film, only to have his character broken by the brutal conditions of Vietnam. His rapid mental unraveling is shocking, leaving only a hollow shell of himself by the end. Steven represents the countless maimed soldiers who were lucky enough to not come home in a body bag, but maybe would have been better off if they had.

THE DEER HUNTER was Meryl Streep’s breakout role, resulting in her own Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress. While she isn’t particularly given a lot to do, she gives the film a softer, feminine edge to counteract the broken machismo that runs through the film. It’s worth also noting that she’s just as tough and courageous as the men.

And then there’s John Cazale, a figure who absolutely must be mentioned. Name five of your favorite films from the 1970’s– odds are he’s in every single one of them. No other actor has made such an impact on the cinematic landscape in only a few films. Cazale acted in just five films before terminal cancer took his life, but his selection was impeccable.

From Francis Ford Coppola’s THE GODFATHER (1972), THE CONVERSATION (1974), THE GODFATHER PART II (1974), and Sidney Lumet’s DOG DAY AFTERNOON (1975), and finally to Cimino’s THE DEER HUNTER– each one an enduring classic in its own right. His particular brand of shuffling fuck-up has been unmatched in the years since, the dedication to his craft urgently apparent in each one.

Cazale suffered through the filming of THE DEER HUNTER, summoning all his strength each day to help Cimino achieve his vision. Sadly, he died shortly before the film was released– but he leaves behind one of the most artistically pure filmographies in all of cinematic history.

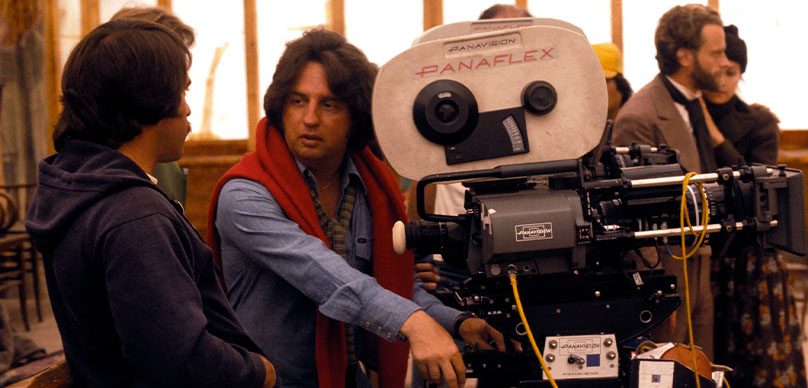

To bring his richly textured vision to life, Cimino enlisted the help of cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond. Shooting on 35mm film in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, Zsigmond crafts an image that retains Cimino’s signature visual style. The saturated, naturalistic colors jump off the screen- particularly, the blood-red bandanas worn by contestants of the Saigon Russian Roulette operation.

Foregoing the use of subtitles to let the audience know when the action shifts to Vietnam and back again, Cimino instead employs a dreary, autumnal color palette for the Pennsylvania sequences while the Vietnam and Saigon scenes explode with intense greens, browns, and oranges.

This approach is mirrored in the camerawork: the smoky, mountainous vistas of Pennsylvania are rendered in slow zoom and dolly shots, while Vietnam is depicted through the jumpy unsteadiness of handheld camerawork. His preference for wide angle lens creates panoramic vistas in which the subject appears tiny against the landscape– undoubtedly influenced by the framing techniques of John Ford. A variety of stock footage is added to the Vietnam sequences to heighten the realism and supplement Cimino’s depiction of The South Pacific as a hellish nightmare.

Cimino’s richly-detailed compositions are a sight to behold. His preference for deep focus and slow-paced editing (courtesy of editor Peter Zinner) allow the viewer to absorb themselves into the world of the story, choosing where they want to look within a frame. As a result, we never see the same movie twice– there’s always something different to notice in each scene.

Stanley Meyers contributes the film’s haunting score, most notably the elegiac “Cavatina”, or as it’s better known: “The Theme From Deer Hunter”. Even if you haven’t seen THE DEER HUNTER, you’ve more than likely heard the somber mandolin strings of “Cavatina” at some point in your life.

It’s an iconic composition that has aged as gracefully as the film itself. Cimino also uses an inspired mix of source music that gives the film its rough-edged, blue collar patina. Frankie Valli’s “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” recurs throughout the film, sounding like it’s been beaten into submission by the bar’s junky jukebox speakers.

Traditional Eastern European polka and folk songs during the wedding sequence gives us a great deal of insight into the characters’ cultural heritage– a tactic that arguably inspired director James Gray in his own intimate depictions of modern immigrant families decades later.

One of the most striking uses of music in the film, however, is Cimino’s incorporation of a non-diagetic choral piece/choral hymnal during the scene’s titular deer hunting sequences. The foreboding, majestic voices hang in the mountain’s hazy air as De Niro maneuvers across the rocky landscape in pursuit of his prey.

It’s at once both unsettling and beautiful, suggesting an uneasy harmony between man and nature. Or perhaps it’s subtly commenting on the cycle of life and death. That’s the beauty of film though– every interpretation is valid.

Speaking of the cycle of life and death, the film uses both ritual and liquid as potent metaphors. THE DEER HUNTERbookends with a pair of celebrations, albeit differing drastically in tone. In the beginning, a wedding is the cause for raucous, drunken revelry. Liquor flows freely and several toasts are made.

As I wrote before, this symbolizes an America drunk off its victory in World War 2 and confident in a similar outcome on the eve of their entry into Vietnam. Water is used to great effect in the Vietnam sequences as a sort of torturous cleansing agent, traumatically detoxing the characters of their confidence and innocence. The end of the film is like a great national sobering, closing with both a somber funeral and an epilogue involving coffee instead of alcohol.

Perhaps the liquid metaphor is reading into the film a little too much, but this is Cimino we’re talking about here– I would be doing a disservice to the man’s spirit if I didn’t indulge myself a little.

Cimino’s signature storytelling themes are perhaps at their most potent in the context of THE DEER HUNTER. The effects of fractured male camaraderie are soulfully explored as the friends literally go through hell and back. The film is very much a love story– the love between brothers. Sure, they bust each others balls on a frequent basis, but it’s done so out of a deep, profound affection.

Additionally, Americana imagery is on full display, much more so than any other of his films. What’s striking about their incorporation here is the deeply ironic, bittersweet implications they take on within the events of the story. The film famously ends with the characters somberly singing “God Bless America” after a funeral that has effectively stolen their innocence.

Hollywood executives were furious over the film’s ending, and they accused Cimino of anti-patriotism. Much has been written about its inclusion in the story, so I’ll simply add that its presence is well-justified, and serves as a pitch-perfect coda to Cimino’s weary tale of innocence lost.

Any way you slice it, THE DEER HUNTER is inarguably the high point of Cimino’s career. The large scope and broad canvas afforded to him by the subject matter made for emotionally arresting cinema, but it also enabled his indulgent tendencies. Indeed, many of the same traits that would spell his downfall in his very next film (1980’s HEAVEN’S GATE) are present here. There’s long sequences that bog down the pacing, and a pompous sense of grandeur and grandiosity liberally applied to the proceedings.

The tone almost seems to explicitly tell you: “This is one of the greatest films ever made”, but in this case, it actually is. This is a film where Cimino put a live round into the gun chamber during the filming of the Russian Roulette sequences in order to heighten the actors’ tension– with that degree of ballsiness and dedication to craft, greatness is simply inevitable.

There was a lot of critical revisionism going around in the wake of the HEAVEN’S GATE disaster, but with five (well-deserved) Academy Award wins and a secure spot in the National Film Registry, THE DEER HUNTER is an undeniable masterwork that’s just as relevant and arresting today as it was in 1978.

HEAVEN’S GATE (1980)

A gigantic albatross. A modern masterpiece. The worst film ever made. The best film ever made.

Few films swing so wildly between those two poles of public perception. No other director experienced so quick a career-ruining plummet from monumental heights. No other film has had such a wide-ranging effect on the industry at large, effectively ending the era of director-dominated filmmaking and ushering in a time of high-concept studio blockbusters.

This is the legacy of Michael Cimino’s HEAVEN’S GATE (1980). His third feature film was his most ambitious project, and resulted in becoming the most expensive film ever made at the time. However, the excessive stylistic indulgences glimpsed in THE DEER HUNTER (1978) matured fully into a debacle– a box office disaster that sank its parent studio and effectively cut a gifted director down in his prime.

It has been thirty three years since Cimino’s darkest day– more than enough time to pass for a critical reassessment, free of the baggage surrounding its release. Its 219-minute initial running time cut down to an impotent 149 upon release, HEAVEN’S GATE was recently restored to Cimino’s original vision and premiered at the 2012 Venice Film Festival— to rave reviews.

Judged by its own merits, HEAVEN’S GATE could be considered one of the greatest films of all time, a staggering masterpiece of epic proportions and scope that rivals the likes of LAWRENCE OF ARABIA (1962) or GONE WITH THE WIND (1939).

After the runaway success of THE DEER HUNTER, Cimino chose a long-gestating project originally called THE JOHNSON COUNTY WAR as his follow-up. Emboldened by his Best Director and Picture Oscars, he was determined to make The Greatest Film Of All Time, the pursuit of which would become his undoing.

Set in Wyoming in the dying days of the Old West, HEAVEN’S GATE tells a version of the eternal American conflict: natives vs. settlers– however, it’s not cowboys and indians that Cimino’s concerned with. His natives are the American-born men of privilege, the settlers a massive wave of Eastern European immigrants trying to realize their own version of The American Dream.

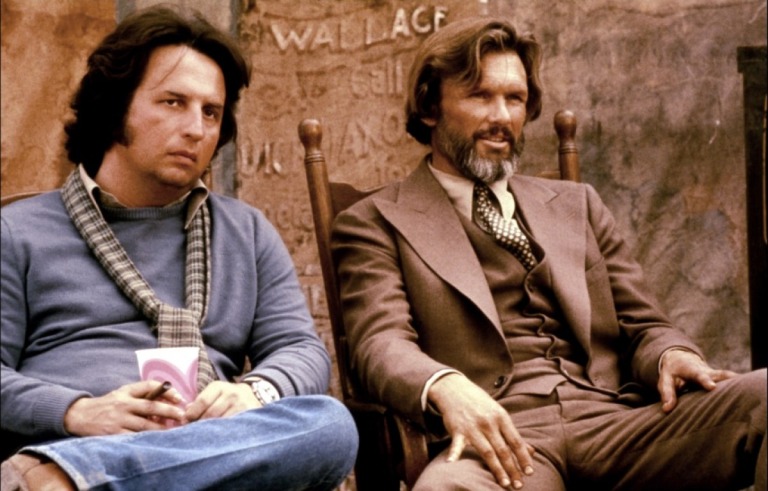

The settlers have been stealing the cattle of wealthy landowners for food. As each day passes and more immigrants arrive by the train load, these powerful landowners realize something drastic must be done to rid themselves of their pests. It’s into this uneasy environment that James Averill (Kris Kristofferson), a Harvard-educated man of privilege and US Marshall, arrives at the bustling boom town of Casper, Wyoming.

He immediately comes into conflict with the landowners, led by the cunningly deceitful Frank Canton (Sam Waterston), who have devised a death list that calls out the names of several immigrants suspected of thievery and anarchy.

As he becomes acquainted with the town and befriends the settlers, Averill cultivates a romance with Ella Watson, a beautiful bordello madam. Promising to take her away from her brothel, Averill vies for her affection in competition with Nathan Champion (Christopher Walken), a skilled hunter employed by the wealthy landowners to maintain the law with deadly force.

When they find out a team of mercenaries are descending on the town to execute the landowners’ death list, Averill and Champion find themselves unlikely allies in the attempt to marshall the distraught settlers into defending their home.

The truth is, with a running time of three and a half hours, no short synopsis of HEAVEN’S GATE is going to perfectly encapsulate Cimino’s richly detailed and layered story. Of all the reason’s cited for the film’s failure at the box office, Cimino contends that it was the neutered running time that excises a substantial amount of scenes necessary for the full impact of the story.

Luckily, now that the film has been restored to its original length and has become the sole version publicly available, we can see the story as it was first intended.

Cimino is well-known for commanding strong performances from his cast. Kristofferson owns the film, depicting Averill as a weary, principled man uncomfortable with luxury and excess. His transformation (taking place over the span of thirty years in the film) from wide-eyed, energetic college graduate to dim-eyed burnt-out aristocrat is stunning. His Averill is a quiet, dignified man that’s equally ferocious as a lover or a fighter.

Walken delivers an equally compelling performance, capitalizing on the success of his past collaboration with Cimino that resulted in a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. His Nate Champion, mustachioed and assertive, is a cunning marksman who only shares Averill’s passion for justice when it affects him personally.

Walken is given an introduction in one of the scene’s most iconic sequences, where he’s seen as a shadow behind a hanging sheet through which he mercilessly shoots a settler. When his face comes into view in the jagged hole left by his buckshot, it is pure cinema.

In a film rife with such masculine themes, French actress Isabelle Huppert’s presence is a refreshing one. As Ella Watson, essentially a hooker with a heart of gold, she is the crucial motivating factor for both Averill and Champion. Upon the film’s release, many found it strange that an overtly French woman was living out in the Wild West, and I can’t say that I disagree with them.

While Huppert does perfectly fine in the film, she does take some getting used to. That said, she gives the film an air of Old World charm whenever she’s present.

Cimino fills out his supporting cast with a number of recognizable faces. Jeff Bridges returns for his second collaboration with Cimino by playing John Bridges, a bearded saloon owner who leads the settlers to charge against the approaching aggression. The talented John Hurt, with his shock of red hair, plays William Irvine– an old Harvard friend of Averill’s whose rebellious, rowdy ways have distilled into an uneasy disillusionment with the wealthy elite that he’s surrounded himself with.

Though he fights on the side of the bad guys, he is the sole voice of conscience in their ranks– but even all his of education and sympathy won’t save him from himself.

As the film’s main antagonist, Sam Waterston is the picture of mustache-twirling devilishness. He’s a hardliner with little regard for the poor and the desperate. His cowardice– meant to symbolize Cimino’s contempt for the greater cowardice of the self-serving wealthy– is repugnant and deceitful, and leads directly to his end at the hands of Averill.

The underrated Brad Dourif is credited only as “Mr. Eggleston”, a thick-accented immigrant who finds the courage to lead his people into battle. Curiously enough, Willem Dafoe and Mickey Rourke also show up within in the film, albeit in “blink and you’ll miss it” cameos. I didn’t see them when I watched the film, but apparently they’re in there somewhere.

To create the film’s sweeping look, Cimino collaborated with his cinematographer for THE DEER HUNTER, the great Vilmos Zsigmond. Shot on 35mm film in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, Cimino’s signature visual style is consistently reproduced. The striking vistas of Wyoming are well-suited to Cimino’s panoramic frames, and when combined with his well-placed crane and dolly-based camera movements, the film takes on the gravitas of a sweeping epic.

When the film was released, it notoriously featured a heavily sepia-hued color scheme, to the point where it looked like the film had been dragged through mud. Thankfully, as part of the Criterion Collection’s extensive restoration, Cimino’s definitive cut now features a naturalistic, vibrant and even color scheme that renders his vision with crystal clarity.

Zsigmond’s wide angle lenses capture dramatic skies with startling detail, as well as heavenly shafts of light that stream in from windows for an almost operatic effect. The symmetrical framing, combined with incredibly deep focus, creates a staggeringly immersive picture.

Art Director Tambi Larsen provides impeccably-detailed production design that allows Cimino to work within a fully realized period environment that can accommodate his more-outrageous demands (a well-known story is that Cimino had the entirety of his Casper town set torn down and rebuilt several times to his specifications).

For the film’s music, Cimino recruits David Mansfield, a young musician who also appears in a bit part onscreen. His score, adapted mostly from existing Americana folk songs, arranges itself into something more resembling a 70’s style epic. His use of the violin, the fiddle, and the guitar blends together into a theme that sounds a little bit like Nino Rota’s theme from THE GODFATHER (1972) had an affair with Ennio Morricone’s spaghetti western compositions.

The film is also peppered with well-known works like The Battle Hymn of the Republic and The Blue Danube waltz, which cleverly re-appears after the climactic battle in a minor key– providing a somberly ironic counterpoint to the jingoistic sentiment and wide-eyed innocence seen in the film’s beginning.

For Cimino, HEAVEN’S GATE was a huge leap forward, mainly from a technical standpoint. His scope was enormous, calling for hundreds upon hundreds of extras to be present at any given moment. He more or less built an entire town from scratch and populated it with the characters of his story. Because of this, his ongoing exploration of the immigrant experience in America is arguably at its most potent in HEAVEN’S GATE.

The scene where the town reacts in horror as their names are read aloud from a copy of the death list is a gut-wrenching highlight, and one of the clearest examples of Cimino’s confident mastery of his craft.

However, no discussion of HEAVEN’S GATE is complete without acknowledging the elephant in the room. The very same gifts that would boost Cimino to unfathomable heights would also become a curse. Cimino’s demanding directing style on-set earned him the nickname, “The Ayatollah” from disgruntled crew members. His indulgence in long celebration sequences contributed to the bloated running time (if cut right, I think a good hour could be cut out of the film without comprising an iota of Cimino’s vision).

The editing team of Tom Rolf, William Reynolds, Lisa Fruchtman and Gerald Greenberg were at the mercy of Cimino’s bidding, so fault can’t necessarily be traced to them. It’s telling that Cimino reportedly heard that Francis Ford Coppola had shot a million feet of film on APOCALYPSE NOW (1979) and felt compelled to beat Coppola’s record. It probably didn’t help that his producing partner Joan Carelli enabled his excessive tendencies by not reigning him in.

Ultimately, the overwhelming success of THE DEER HUNTER boosted Cimino’s ego into a place where he believed he was infallible. Careless cost overruns and shooting delays threw the film recklessly over budget, and the subsequent final product alienated audiences enough to stay away in droves.

The resulting fiasco nearly sank United Artists, and ended an era of innovative films that saw the director as the de facto “author” of a film. For Cimino, the disaster of HEAVEN’S GATEmade him a pariah, effectively throwing his career into a state of dormancy for the ensuing five years.

The glory of Oscar gold and the temptations of infinite money and final cut were the catalysts for Cimino’s downfall. In the decades since, HEAVEN’S GATE has become something akin to a cautionary tale to would-be directors, warning them of the dangers of excess and ego. Reactions to the film in recent years are still as polarized as they have ever been.

To me, however, the film is undeniably accomplished– a masterpiece that holds its own against THE DEER HUNTER. When the baggage surrounding the film’s history is taken away and it is allowed to stand on its own merits, one can clearly see the staggering grasp of craft on display. While I realize the film is deeply flawed as a result of Cimino’s excesses, HEAVEN’S GATE has aged incredibly gracefully.

DVD culture has given rise to an appreciation to “The Director’s Cut” (retroactively saving many films from failure), and HEAVEN’S GATE is the grandfather of them all.

Cimino’s original vision is a thing of arresting beauty, and startlingly prescient in its subject matter. The story of HEAVEN’S GATE, indeed a number of Cimino’s films, strikes right at the heart of America’s deepest internal conflict. America was founded on the idea that all people are created equal, but our society is structured to favor the wealthy and unequal distribution of wealth.

To Cimino, it’s not birth that makes us equal. Birth only makes us lucky, or unlucky, depending on the lifestyle we’re born into. The only true equalizer is death, where money and status have no bearing.

HEAVEN’S GATE is the kind of film that I cannot make an unequivocal, collective statement about in regards to its quality. It’s a film that has to be experienced and judged on an individual basis. No two people will come to the same conclusion. What I can say, without reservation, is that HEAVEN’S GATE will elicit a reaction from you. Whether that’s positive or negative, I don’t care. Art is art by virtue of creating a reaction. By that logic, HEAVEN’S GATE thus is, inarguably, a work of true art.

YEAR OF THE DRAGON (1985)

The complete and utter failure of director Michael Cimino’s film HEAVEN’S GATE (1980) left a number of bodies in its wake, not the least of whom was Cimino himself. The next five years would be the darkest time of his career– a forced, unwanted sabbatical in which he couldn’t get any films off the ground.

He floated noncommittally between various projects like THE POPE OF GREENWICH VILLAGE and BORN ON THE FOURTH OF JULY. In that time, his biggest success as a director was managing to get hired to helm FOOTLOOSE, only to be fired before production started when his excessive set design demands led studio executives to believe they were making another HEAVEN’S GATE.

Finally, in 1985, Cimino returned to cinemas with a completed picture. Titled YEAR OF THE DRAGON, Cimino collaborated on the script with Oliver Stone, under the supervision of producer Dino De Laurentiis. Set in contemporary New York City, YEAR OF THE DRAGON tells the story of Stanley White (Mickey Rourke), a Vietnam veteran and decorated lawman working the city’s Chinatown beat.

He comes into conflict with Joey Tai (John Lone), an ambitious young businessman who violently assumes control of the city’s Triad operations. As a shaky ceasefire between the Triads and the police bubbles over into violence, White finds his family drawn into the conflict and his pursuit of Tai becomes a personal vendetta.

This was my first viewing of YEAR OF THE DRAGON, and had I not watched in the context of Cimino’s career, I probably wouldn’t have thought much of it. In an approach that’s unexpectedly un-Cimino, the film doesn’t pretend to be anything more than what it is– which is a gritty, pulpy noir film that capitalizes on the 1980’s (and Oliver Stone’s) fascination with Asian culture. In that light, and considering the disaster of Cimino’s previous film, YEAR OF THE DRAGON arguably holds up well.

The craft is strong and competent, but there’s something missing in the execution. There seems to be a degree of reserve– Cimino’s direction doesn’t have the same kind of confidence that it used to. It’s akin to a war veteran who walks with a limp: the functionality and drive is still there, but the malady hobbles its operation; a limp that impedes the reaching of its full potential.

Cimino eschews most of his regular collaborators, opting for a creative refreshing both in front of and behind the camera. While Rourke previously appeared in HEAVEN’S GATE, he was so underutilized that he might as well have never been in it. Given the limelight here, Rourke does his best Bruce Willis impersonation as the grizzled, emotionally fractured Stanley White.

He’s not exactly a savory protagonist– his experiences in Vietnam led to a head of grey hair and a particularly vocal distaste for Asians. It’s interesting to see him in a pre-boxing career performance, where his face hasn’t been pounded into hamburger. Ultimately, though, it’s a bizarrely eccentric performance that does neither Rourke or Cimino any favors.

As the ruthless Joey Tai, Lone is suave and poised. He’s sophisticated and elegant, but its a facade that hides a ruthless monster who would decapitate a member of his own family– and that’s not a metaphor, he actually does that. The character is a decent villain, but it’s nothing we haven’t seen before. Ariane (no last name is credited to her in the film) plays Tracy Tzu, an ambitious and street-smart television reporter that starts a love affair with the married White.

Films in the 80’s and early 90’s seem to have an obsession with the overbearing TV reporter character– April O’ Neill from TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES (1990) being a prime example. Ariane was an unknown when Cimino cast her, and for good reason– she’s quite simply a terrible actress. Her delivery is wooden, hollow, and stilted. Her apartment in the film is awesome, but her physical presence in the film distracts from the main narrative– providing only a half-baked romantic arc for Rourke.

The supporting cast is lackluster. Not that the actors are miscast or deliver bad performances, it’s just their characters don’t have much to do. Caroline Kava plays Connie, Rourke’s screeching harpy of a wife. She’s supposed to only be thirty five in the film, but she looks like she’s closer to fifty.

She spends most of the film wallowing around, feeling sorry for herself that her marriage to White is crumbling, and when she’s killed halfway through the film, it had no emotional resonance for me at all. I was actually glad to see her character bow out. Ray Barry shares a couple scenes with Rourke as Louis Bukowski, White’s colleague and closest confidant.

However, his character is a stock figure too. He’s just someone for Rourke to bounce lines off of and discourage him from completing his arc. Barry is believable in the role, but his character isn’t given much of a chance to shine.

For the look of the film, Cimino switches up some key elements while retaining the core of his signature visual style. YEAR OF THE DRAGON is Cimino’s first collaboration with new Director of Photography Alex Thompson. Shooting on 35mm film in Cimino’s preferred 2.35:1 aspect ratio, they depict a claustrophobic, gritty New York by using wide lenses in tight spaces.

While Cimino employs dolly, zoom, and crane shots to add scale to the story, there is much more of a pared-down aesthetic at work. Colors are naturalistic, yet drab– save for the bright pop of reds, which are an appropriate visual motif considering the Chinese imagery that the story requires. The deep focus renders decrepit slums and postmodern penthouses alike with staggering amounts of detail.

There are no panoramic mountain vistas to be seen here (save for the film’s scenes set in China), so instead Cimino swaps snow-capped peaks for the gleaming steel towers of Manhattan.

Music is provided by David Mansfield, who previously supplied the score for HEAVEN’S GATE. For YEAR OF THE DRAGON, Mansfield constructs a score that blends Asian influences with string-based compositions not unlike THE DEER HUNTER’s Cavatina. It’s not particularly memorable, but it adheres to Cimino’s preferred musical palette quite well.

Cimino also employs a variety of source cues like rock and choral church hymns, as well as those strange synth-based traditional/pop tunes you typically hear in hole-in-the-wall Chinese restaurants.

By abandoning any pretense of Great Filmmaking (the likes of which sunk HEAVEN’S GATE), Cimino turns in a fairly entertaining (albeit neutered) film. Action is explosive, often appearing out of nowhere (a shooting in a crowded Chinatown club is especially heart-stopping). The pacing charges along, never meandering like it did in Cimino’s previous works (a first time collaboration with editor Francoise Bonnot might be to thank for that).

The final shootout is moody and expressionistic– one of the most clever showdowns in recent memory. It’s a sublime moment of cinema and a reminder of the pure talent Cimino holds within himself. Overall, there seems to be a real sense of lessons learned where it counts.

Cimino also finds plenty of opportunity to indulge in his thematic preoccupations. Americana imagery is seen in the form of American flags, and references to railroads– an apt allusion considering Chinese Americans’ own experience in that chapter of history. The immigrant experience in America is front and center. Their spiritual ceremonies– mainly funerals– are worked into the story and rendered in striking detail.

Cimino’s fascination with Christian imagery also re-appears here, in the form of Stanley White’s own religious convictions (or lack thereof) in a cathedral during his wife’s funeral. Throughout YEAR OF THE DRAGON, Cimino uses funerals as an effective focal point on which to compare East and West cultures.

YEAR OF THE DRAGON sees Cimino crafting a story set in his own hometown, so it naturally benefits from the tactile sense of place Cimino brings to the film– an ironic notion, considering the majority of the film sees Cimino eschewing his preference for location shoots, and choosing instead to use studio sets and backlots.

The set design, courtesy of Production Designer Wolf Kroeger, was apparently so authentic-looking that Stanley Kubrick (who had attended the premiere) did not believe Cimino himself when told that none of the locations actually existed in real life. Little anecdotes like this go a long way towards illustrating Cimino’s unparalleled attention to detail.

Negative criticisms of the film were plenty upon the film’s release, as has become the standard for Cimino’s work. A lot of the controversy centered around his supposedly false and blatantly racist depiction of New York’s Chinatown, and Chinese culture at large. Criticism of this sort helped undermine any shot of success for HEAVEN’S GATE, when it was found Cimino recklessly warped the truth behind historical figures and events entirely into the realm of fiction to suit his narrative.

Indeed, there’s many justifications for similar criticism in YEAR OF THE DRAGON, but Cimino contends that the subject matter of his story demanded a degree of damning treatment. It’s not exactly the best defense on his part, and helps explain why he fell out of favor increasingly politically correct world.

All in all, YEAR OF THE DRAGON marks Cimino’s return to filmmaking after five years of exile. By eschewing his grand, operatic pretensions, the back-to-basics approach works to create a modestly effective and lean thriller. That said, the film suffers from a profound hesitancy; a doubt in confidence that impedes the story from realizing its full potential.

Whether Cimino exhausted all his remarkable talent in the making of HEAVEN’S GATE remains to be seen, but for the time being, YEAR OF THE DRAGON stands as an underrated film that would be an exceptionally strong effort by most other directors’ standards.

THE SICILIAN (1987)

After YEAR OF THE DRAGON’s (1985) modest success, director Michael Cimino again found himself as an employable filmmaker. While it didn’t reach the heights that THE DEER HUNTER (1978) or even THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT(1974) did, Cimino could at least show that he was able to overcome the catastrophe that was HEAVEN’S GATE (1980). However, that success was short-lived, as it further emboldened Cimino’s indulgent eccentricities and led him further down the path of obscurity.

Two years after YEAR OF THE DRAGON, Cimino re-teamed with his HEAVEN’S GATE producer, Joann Carelli, to make his fifth feature film– THE SICILIAN. With a story based off a novel by Mario Puzo that was considered the true literary sequel to “The Godfather”, expectations for another cinematic masterpiece like Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 adaptation were understandably high.

The producers took a gamble by hiring Cimino, believing that he still was capable of delivering a film on par with THE DEER HUNTER. To hedge their bets, they brought an uncredited Gore Vidal on as the screenwriter (final credit went to Steve Shagan). Unfortunately, their faith was misplaced– the final result was an incoherent mess capped with a bizarre lead performance that continued Cimino’s road to ruin.

Puzo’s source novel was a much sought-after film property, as it fleshed out Michael Corleone’s exile in Sicily and his encounters with Salvatore Guiliano, a bandit turned folk hero. Due to copyright issues, however, the cinematic adaptation had to sever any connection to THE GODFATHER whatsoever. As a result, Vidal’s screenplay shifted the focus to Guiliano himself, depicting his rise and fall as a transformative figure in Sicilian history.

As filmed by Cimino, the story follows Guiliano (Christopher Lambert) and his loosely organized militia during the early 1950’s as they try to subvert the Italian government and established Sicily as an American state— weird, I know. Like Robin Hood, Guiliano roams the countryside, stealing from wealthy property owners and giving back to the poor.

As his infamy spreads, his ego gets the best of him (something tells me Cimino didn’t realize the irony here). This leads to the ruthless assassination of his own men, whom he suspects of betraying him. His megalomania grows to a point where he believes himself to be more powerful than his financial benefactor, the Mafia Don Masino Croce (Joss Ackland). Enraged by Guiliano’s hubris, the Don conspires with Pisciotta (John Turturro), Guilano’s cousin and closest friend, to put Guiliano down for good.

There is a great movie in this material, but it is not this film. The story is hamstrung by a frankly bizarre performance by Highlander himself, Christopher Lambert. He certainly looks the part as the courageous, dashing hero, but there’s a strange, dead intensity in his eyes that comes off as off-putting. It’s like a vanity performance by someone who thinks they’re more charismatic and talented than they actually are.

His laughable delivery manifests in barking his lines with an off-kilter intensity that sounds border-line mentally challenged. Even taking into account Cimino’s eccentric direction, Lambert still is the film’s weakest link. There’s a reason he fell off the acting map after the mid-90’s.

The supporting cast fares much better. The always-impeccable Terence Stamp plays Prince Borsa, a dandy aristocrat who finds himself the frequent target of Guiliano’s crusade. He spends much of the film reclining in an opulent watchtower attached to his country estate, listening to old opera records. Stamp depicts Borsa as a smart man whose distance from the hardscrabble peasants have made him out of touch and irrelevant.

It’s a reserved performance, to be sure, but Stamp never hits a wrong note. As Don Masino Croce, Joss Ackland cultivates a strange father/son-friend/enemy relationship with Guiliano. He thinks of Salvatore like a son, but the Mafia code of honor dictates a degree of respectful animosity when he breaks rank. Croce ultimately comes off as a dignified, almost sympathetic antagonist.

John Turturro has perhaps the meatiest role in the film– that of Pisciotta, Guiliano’s cousin and best friend. Initially presented as somewhat of a fool, he transforms into a hardened killer in the service of Guiliano’s mission. However, he ends up being more of a Judas, becoming the instrument of Guiliano’s downfall when he realizes their fight can’t be won.

He receives his comeuppance in a very satisfying way that ties into Guiliano’s earlier methods of branding traitors. These moments are where the influence of Puzo and THE GODFATHER are the most potent.

The supporting cast is rounded out by fine performances from Richard Bauer, a seasoned character actor, as Guiliano’s crippled godfather, Hector, and the fire-headed Giulia Boschi as Giovanna, Guiliano’s wife. It’s a little perplexing when Cimino’s supporting players are well-cast, but his lead is completely wrong for the part. However, we should come to expect odd casting choices from Cimino by now.

To capture Sicily’s expansive vistas, Cimino again works with cinematographer Alex Thomson. I’m aware that the film was shot on 35mm on the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, but I unfortunately was not able to see it in the way Cimino intended– the only available home video release of THE SICILIAN was released at the dawn of DVD, when lazy pan-and-scan presentations were the norm.

However, many of Cimino’s signature visual elements are present: deep focus, symmetrical frames, dramatic mountain expanses, and a masterful sense of epic scope achieved with dolly, crane, zoom, and moving POV/on-rails camerawork. Indeed, THE SICILIAN marks somewhat of a return to form for Cimino’s grand, romantic style of filmmaking.

Early in the film, Cimino employs an interesting cutting technique that he never revisits again. He symmetrically frames an image with the subject in the center, as we’re tracking forward or away from him/her. Then, he cuts right on the 180 degree line, flipping to front and back views in a disorienting jumble of visual information.

While the technique is a little strange, it seems to come from a true creative drive within Cimino– a vitality and willingness to experiment that hasn’t been since since THE DEER HUNTER. It’s too bad that this courage doesn’t persist through the remainder, as it could have resulted in a very different, very dynamic experience.

Warm color tones complement a naturalistic lighting scheme, despite claims upon the film’s release that its visuals were smeared and muddy. Ultimately, despite the high production value, the look of the film feels somewhat neutered. It’s as if THE SICILIAN was a TV Movie Of The Week blessed with an unusually large budget. Overwrought dialogue and a weird sense of dramaturgy contribute to a tone that’s off-balance and uneven. As a result, the whole experience feels lackluster, strange, and decidedly un-cinematic.

David Mansfield once again provides music for the film, crafting a sweeping, romantic score that evokes Nino Rota’s iconic work for THE GODFATHER– which is appropriate given the source material. Well-placed opera tracks also dot the soundscape, in addition to the unexpected inclusion of swing music. One of my favorite musical moments was during the wedding scene, which takes place on top of a mountain.

Since they have no instruments or record players, Guiliano’s poor guerrillas loudly (and horribly) sing the swing music themselves. It’s a sublime moment that wordlessly communicates the themes of the story and endears us to the characters.

It’s easy to see why Cimino was lured to the story of THE SICILIAN, besides the intention of making the next GODFATHER. It’s an unconventionally personal film for Cimino, in which the action takes place in the land of his ancestors. There is a clear love and exploration of his heritage at play here, which allows him to focus his preoccupation with cultural persecution on a subset of people he identifies with. Ritualistic ceremonies like weddings and funerals are all important story events that allow Cimino to explore his own relationship with religion.

This being a Cimino film, there is a lot of detail to soak in. One of the film’s strongest aspects is the production design, by recurring collaborator Wolf Kroeger. Together, Kroeger and Cimino craft an authentic and immersive portrait of mid-twentieth century Sicily, a land of great natural beauty and history. But even in a setting that’s half a world away from America, Cimino finds regular occurrence to reference the United States.

He even goes so far as to prominently highlight one of the more eccentric goals of Guiliano’s crusade, which was to make Sicily an American state. Personally speaking, I found this to be a very strange, naive goal– even if it was true in history (Cimino has a habit of playing fast and loose with historical events to fit his purposes).

States like Alaska and Hawaii already are stretching the conceptual boundaries of American statehood by virtue of not being connected to the contiguous US, so the notion of establishing an Italian island halfway across the world as the 51st state is, frankly, nonsense. However, it is an effective subplot if its aim is to communicate the insular, megalomaniac nature of the story’s protagonist. If he thinks that’s a realistic goal, he’s crazy.

Upon its release, THE SICILIAN was essentially a flop. It made less than half of its budget back, and was entangled in a nasty lawsuit that pitted Cimino against his producers in a battle over running time. The production echoed that of HEAVEN’S GATE, with the film falling behind budget and schedule, and Cimino fighting his backers over final cut.

The finished film clocked in at just under two hours, while Cimino’s cut ran almost twenty minutes more. However, the longer version of THE SICILIAN wasn’t fated to have the same critical re-appreciation that HEAVEN’S GATE was blessed with. Even in the director’s cut I screened, the final result is a jumbled, largely incoherent exercise in complacency.

There’s a few sparks of true inspiration and glimmers of greatness, but they are too few and far between to surmount the film’s profound flaws. Barring an exhaustive restoration on par with HEAVEN’S GATE, I can’t imagine THE SICILIAN’s place in cinema garnering a better standing anytime soon.

THE SICILIAN is currently available on a standard definition DVD via MGM, but I wouldn’t recommend it. Due to being dumped as a minor catalog release in the format’s early days, Cimino’s original widescreen framing and other details are lost to a claustrophobic pan-and-scan scan formatted for older television sets.

DESPERATE HOURS (1990)

Ever since the disaster of 1980’s HEAVEN’S GATE, director Michael Cimino had been in a career tailspin from which he could not recover. Each successive, new project (themselves many years apart from each other) were met with an increasing chorus of negativity and a diminishing box office take. Despite his best efforts, an increasingly vain self-image and eccentric vision continued to betray him. His sixth feature, 1990’s DESPERATE HOURS, could’ve been a bid to reclaim his former glory with a gritty, contained thriller.

Unfortunately, it was met with a profound indifference, signaling the dying throes of Cimino’s relevance. As of this writing, DESPERATE HOURS was the last film of Cimino’s to ever be released in cinemas.

A remake of the 1955 film (and hit Broadway play) of the same name, DESPERATE HOURS features Mickey Rourke as Michael Bosworth, a charismatic criminal that stages a shockingly simple jailbreak and takes over an elegant, comfortable house in the suburbs as his hideout.

While they wait for Bosworth’s lawyer-turned-lover to spirit them away to freedom, Bosworth and his posse hold the house’s inhabitants– the fractured Cornell family– hostage and subjects them to several days’ worth of psychological trauma.

DESPERATE HOURS marks Rourke’s third collaboration with Cimino, and it’s not a good sign when he’s one of the most watchable things about the movie. He paints Bosworth as a civilized psychopath; a whip smart man with thuggish instincts and a dime-turn ferocity. He calmly commands his hostages to do his bidding in a manner that’s so respectful it’s unnerving. While it’s an original characterization, Rourke ultimately can’t transcend the well-worn material and Cimino’s overwrought sense of drama.

Anthony Hopkins is one of the best actors of his generation, but his sole collaboration with Cimino as Tim, the Cornell family patriarch, is puzzlingly underwhelming. I’d even go as far as to say that Hopkins is utterly miscast in the role. Tim Cornell is a sophisticated man of taste, enabled by a lawyer’s salary.

He’s also a philander and a bad husband/father– when we first meet Tim, he’s in the midst of a messy divorce with his wife, Nora (Mimi Rogers). As the man who must live up to his responsibilities and deliver his family to safety, his arc is theoretically the more interesting one in the film, but Hopkin’s delivery falls flat. I don’t discredit Hopkins with that statement, as he obviously is giving it his all– rather, it’s once again a reflection on Cimino’s uninspiring direction.

The supporting cast doesn’t fare much better. Elias Koteas, who is perhaps my favorite character actor, was the sole highlight of the film for me. He plays Wally Bosworth, Michael’s jittery younger brother. His performance has a greaser-vibe to it, channeling a countercultural energy and spirit that brightens the dour mood every time he appears on-screen.

David Morse is equally sympathetic as Albert, the third wheel of the criminal posse and the emotional wild card. Morse plays Albert as an impotently frustrated man who yearns to be smarter than he actually is. This complicates the fact that he has much more of an imposing frame than his two counterparts, which adds a layer of tension where the viewer wonders if he might bite the hand that feeds him, so to speak.

Morse conveys depths of information about his character without the luxury of dialogue, which leads me to believe that his is the most accomplished performance in the entire film.

Cimino’s stories are decidedly muscular and brawny– which usually means women are placed predominantly into supporting character roles. As Nora, the Cornell family matriarch, Mimi Rogers is as strong, if not stronger than her husband. This strength initially comes across as a little off-putting during her early squabbles with Tim, but it soon morphs into a rock-solid determination and desire to see her family safely through the ordeal. As Bosworth’s lover Nancy Breyers,

Kelly Lynch is appropriately sexualized to match the brutish sensibilities of her paramour. Her feminism is strikingly different from Rogers’– it’s a dainty, delicate feminism that is easily manipulated and broken down. Lynch spends most of the running time delivering her lines in between sobs, but manages to transcend her situation to become one of the key agents of Bosworth’s demise.

Additionally, Lindsay Crouse appears as FBI Agent Chandler, a laughably ridiculous stereotype of your typical gruff police chief. Barking every line like she’s an angry Danny Glover, Crouse is the most curious aspect of the entire movie. She’s doggedly determined, kind’ve like an angry poodle that won’t stop barking.

Her approach to policework is dodgy as well, manifested best in the scene where she announces her presence to Tim– the very man she’s trying to save– by pointing a gun to his head. This is the kind of bad, ill-advised performance that people make drinking games out of.

To bring Cimino’s home invasion potboiler to life, he enlists the services of a new cinematographer, Doug Milsome. While shot on 35mm film, this is the first of Cimino’s works not to be photographed in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Instead, Milsome composes a 1.85:1 frame that suggests the distinctive air of a second-rate television film.

Make no mistake, DESPERATE HOURS is one of ugliest, if not the ugliest, film done by a director otherwise noted for visual flair. The narrower frame takes away from the power of Cimino’s mountain vistas– a major disservice to a film that places itself firmly within the natural beauty of Utah. The colors are natural, albeit subdued and drab.

Instead of using well-composed frames to convey narrative and information, Cimino’s restless camera changes angles on an whim by utilizing unmotivated dolly or zoom moves. The deep focus provides for ample opportunities to show off the details of Victoria Paul’s production design, but Cimino takes no such opportunities. Visually, DESPERATE HOURS is an exercise in lazy filmmaking of the highest order.

The music, provided by regular Cimino collaborator David Mansfield, is laughably inappropriate. Criticized as one of the film’s biggest flaws upon its release, Mansfield’s score comes across as an incoherent oddity. The intent is present– it’s obvious that Cimino and Mansfield fancied a big, brassy old-school thriller score that harkened back to the 1950’s– but it feels woefully out of place amidst Cimino’s blandly modern visuals.

It barnstorms across the film’s running time, barely ceasing to bludgeon us over the head with proclamations of “atmosphere” and “drama”. As of this writing, this score would become Cimino and Mansfield’s last collaboration. Much like Cimino’s career itself, their partnership started off strong in HEAVEN’s GATE, but quickly descended into depths of incoherence and indulgence that it could not transcend.

DESPERATE HOURS, also the last of Cimino’s collaborations with producer Dino De Laurentiis, still manages to maintain some of Cimino’s thematic preoccupations. Just like Rourke’s Stanley White character in YEAR OF THE DRAGON (1985), his character in DESPERATE HOURS is a Vietnam vet that lives uneasily with his wartime experiences.

While this manifests itself in the former film as a vicious volatility, the latter film fosters an ideological, megalomaniacal bent in which Rourke’s character breathlessly pontificates on the sad state of American affairs while providing no alternative solutions.

The gorgeous Rocky Mountain locales provide Cimino with ample opportunity to employ his dramatic mountain vistas that creates a mise-en-scene dripping with detail. But Cimino’s films are infamous for their inaccuracies and one-sided storytelling, and some dramatic details– like the presence of motor checkpoints at a state border– are downright ridiculous.

Like his other films, Cimino employs a deliberate sense of pacing, courtesy of editor Peter Hunt. In fact, this is the first film of Cimino’s since THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT (1974) to run under two hours– thanks to Cimino eschewing his tendency to dwell unnecessarily on big setpieces. Unfortunately, Cimino and Hunt aren’t able to channel this newfound brevity into anything resembling suspense– a fatal flaw that ultimately sinks the picture.

DESPERATE HOURS is a largely forgettable film, undone by the overcooked dramaturgy of a tragically deluded director. The lack of creative inspiration on display gives the sense that it was a journeyman, for-hire job on Cimino’s part– a lazy bid to get out of “director jail”. Whether he genuinely wasn’t trying, or if his talent has truly left him, it’s impossible to say.

It’s clear that everyone involved was trying to do their best work, but they are ultimately a sacrifice to the fire of Cimino’s pretensions. If DESPERATE HOURS is anything, (and there’s a strong case to be made that it’s nothing), it is the final nail in the coffin of Cimino’s once-promising career, and the squandered last chance to reclaim his place amongst the greats.

SUNCHASER (1996)

After the dismal reception of DESPERATE HOURS in 1990, director Michael Cimino again went into a self-imposed exile from the screen. It would be six years until he was able to put together another film. By all accounts, Cimino was a washed-out has-been; an irrelevant filmmaking force for almost twenty years. In 1996, he broke his silence with the release of SUNCHASER, a film that initially got Cimino’s hopes up with its inclusion into competition at the 1996 Cannes Film Festival.

However, the film was received by US test audiences so poorly that it was never released theatrically. With this development, Cimino was dealt a killing blow. The once-great director of THE DEER HUNTER (1978) saw his last film condemned straight to video, and his career’s tragic fate was sealed.

In a move that comes full circle with his debut film THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT (1974), SUNCHASER is a modern road film starring mismatched “buddies” who rage against the American landscape in roaring muscle cars. The story follows Michael Reynolds (Woody Harrelson), a young, mild-mannered doctor on the verge of a big promotion.

When he’s kidnapped by his patient– a teenage convict with terminal abdominal cancer named Blue (Jon Seda)– he’s forced at gunpoint to drive his hostage-taker out into Najavo Country in search of a mystical mountain lake with healing powers. Along the way, they form an unlikely bond, and Reynolds decides to risk everything to bring his captor to his destination.

The characters, as written by screenwriter Charles Leavitt, are oftentimes stereotypical and one-dimensional. Even Harrelson and Seda, whose characters actually undergo a transformation, have to contend with cliché plot developments and archetypes. As a man made cynical by virtue of his intelligence, Harrelson is convincing in the role of Dr. Reynolds.

It’s not a particularly memorable performance, but it never feels false either. There’s no doubt that Harrelson is an excellent performer, and – like a consummate professional– he gives everything he has to the lackluster material he’s got to work with.

As a foul-mouthed gangster with a spiritual side, Jon Seda is the most compelling character in the story. He’s overly intense and mean, but one suspects it’s a façade meant to cover up at the sheer terror he feels internally at the prospect of only having two months to live.

He assumes the symptoms of his disease convincingly, and the earnestness in which he believes in the healing lake ultimately renders his character endearing and sympathetic. He’s a by-the-book foil to Harrelson, subverting him and providing conflict at every turn.

The only other cast member worth mentioning is the venerable Anne Bancroft, in an appearance that amounts to a glorified cameo. She plays Reneta Baumbauer, an elderly New-Age hippie who shares a brief ride with Michael and Blue. While her screen time is scant, it’s a testament to Bancroft’s talent that she remains one of the film’s most memorable characters. Unfortunately, Leavitt’s characterization and dialogue leave her with a fairly stock granola-cruncher persona that doesn’t have a whole lot to do other than reinforce the film’s stereotypical New Age themes.