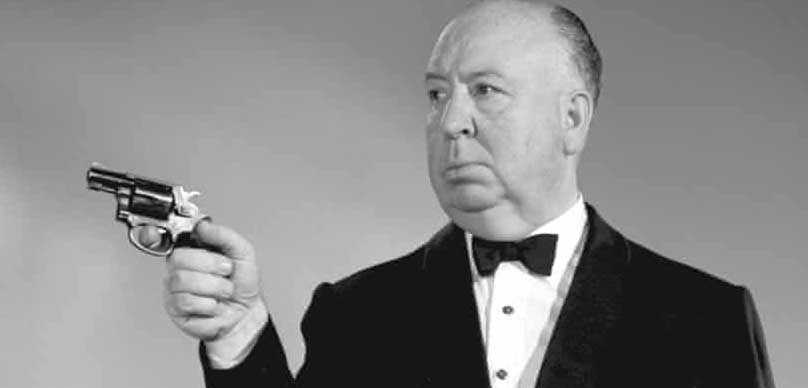

Alfred Hitchcock is the master of suspense. You’ll see what I mean. A hand draws back a shower curtain and a blade appears through the steam. A man descends a staircase, bearing a tray with a glass of milk that appears at once nurturing and suspicious. A young woman, alone in a museum, stares transfixed at a mysterious portrait.

“In feature films the director is God.” — Alfred Hitchcock

A man trips and falls, his vision deteriorating into a disorienting spiral. A woman boards herself up in a house, to escape the incisive beaks of the murderous creatures outside. A man and a woman press up against a windowsill, watching domestic scenes unfold as though on a television screen.

WATCH Hitch20: Exploring Hitchcock’s 20 Works of TV on Indie Film Hustle TV

Docu-series bringing the forgotten skills of Alfred Hitchcock to today’s pro filmmakers, film students, and the wannabe videographer. Experts examine each of the 20 episodes of television that Hitchcock himself directed.

A woman enters a basement, spins around a rickety chair, and finds herself face-to-face with a decomposing corpse. A brooding man wavers on the edge of a wild, windy cliff, before stepping back from the precipice. A prisoner raises his eyes to meet the camera directly and breaks into a smile.

The Cinema of Alfred Hitchcock is such an integral part of the film canon that these descriptions instantly evoke iconic images. The blade in the steam has been reinterpreted so many times throughout the years that the image has taken on a life of its own, beyond the boundaries of the film Psycho.

Alfred Hitchcock’s classic titles feature in most critics’ Best Film shortlist. Indeed, since 2012, Vertigo has beaten Citizen Kane to the number one spot on the revered Sight and Sound critics’ film poll. Hitchcock’s position as a film master is a well-deserved one. Yet in canonizing – and parodying – his work, we often lose sight of how inventive it was. For the ‘Master of Suspense‘ taught us to question both the suspicious and the mundane.

He taught us to see the danger not only in the blade through the steam, but in the empty night sky. He taught us to fear not only the suspicious stranger in the trench coat, but the husband with the glass of milk.

Alfred Hitchcock is undeniably the world’s most famous film director. His name has become synonymous with the cinema, and each new generation takes the same pleasure in rediscovering his films, which are now treasures of our artistic heritage.

Alfred Hitchcock started out in the British silent cinema of the 1920s, which reached its peak with successful thrillers such as “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1934), “Sabotage” (1936) and “The Lady Vanishes” (1938). Recognized as a ‘young genius’, Alfred Hitchcock moved to Hollywood and set about reinventing cinematic tradition, combining the modern with the classic in films such as “Psycho” (1960), “North by Northwest” (1959) and “The Birds” (1963).

Hitchcock gave talented actors such as James Stewart and Cary Grant the chance to play enduring antiheroes and imprinted the public imagination with the myth of the ‘blonde‘, as embodied by Grace Kelly, Kim Novak and Tippi Hedren.

Below I have compiled over 9 hours of the master breaking down his own work as well as many scholars doing the same. As a HUGE Alfred Hitchcock fan I really enjoyed putting this post together. It’s truly like going to film school watching all of these remarkable videos. Enjoy!

96-Minute ‘Masterclass’ Interview with Alfred Hitchcock on Filmmaking

Spoiler

Alfred Hitchcock Analyse

We turn today to Alfred Hitchcock, one of the most remarkable if not the most remarkable and significant of what we might call the great studio directors, the people who worked with great ease and success inside the studio system that developed in the United States began to develop in the United States in more than embryonic form in early systematic form in the silent era, and then was fortified and extended into the great manufacturing mass manufacturing center for dreams and movies, the Hollywood system of the studio of the studio era, and I wanted to begin by saying a word about Hitchcock in relation to that great system. If we think about a famous quotation from the great film scholar, pioneering film critic, Andre balzan, to whom we will return later in the semester, because he is among his other influential comments.

This one is particularly powerful and significant one, the American cinema who said, wrote in 1957, is a classical art. And it’s unclear exactly what he meant by that. But most most critics assume that what he meant by that is that it’s a system that works according to essentially classical genre forms, that, that, that these genre forms have origins behind the movies and that that and that the system works in a kind of generic way.

That at least that’s a part of what he meant, when he called it a classical art. The American cinema is a classical art, but why not then admire it in what in what is most admirable, not only the talent of this or that filmmaker, but the genius of the system. I think I alluded to this phrase or use this phrase earlier in the term and want to do justice to it by acknowledging its origins.

Andre Bowser is also a wonderful book by a film scholar from Texas named Tom Schatz, called the genius of the system. And it borrows uses this quotation as its as its inspiration, and it’s an analysis, systematic analysis of the Hollywood studio system, in which he talks about the interaction of individual agency that writers, the directors, the camera people, and so forth of costumers, the interaction of those creative or semi creative figures with the with the manufacturing and publicity practices and rituals that surrounded the production of movies and books.

He tries to provide a kind of integrated sense of how the system worked to explore what present apparently meant when he talked about the genius of the system, when one way of understanding the genius of the system is to recognize that it creates a an environment, first of all of stability, in which particular filmmakers or particular writers or directors can have confidence, sometimes overwhelming confidence because they’re ordered to do the job by the studio head can have confidence that the job that the genre stories, they’re they’re creating have an audience.

That’s been sort of established by the essentially, assembly line system that develops them the elaborate system of distribution and access that developed in the United States, the major studios, actually, although they only controlled something like 16% of the resources, they have moviemaking actually controlled a much larger percentage of the theaters because many of the theaters either were owned outright by major studios, or until a certain point when the Supreme Court decision divested the studios from rip forced the studios to divest themselves from their theatrical holdings.

When it when the system was in place, it was a monopoly system in which the rich got richer in some sense, the major studios controlled owned many theaters themselves and and by a system of what was called block booking by they forced theaters, not just to book particular films in particular stores that they might like. But MGM would say to theater, independent theater owners, if you want the MGM films, you have to take my whole card, you can’t just choose the Clark Gable movies, you have to choose the whole thing.

This stability created an environment in which in which each student each major studio was confident that it had infected had a captive market for its product and it created an immense sense of stability and confidence that when the system was working at its best and what so what am i Of course, again, because it was a system that was committed to entertaining, the largest number of people that it could reach as possible.

It meant that there were certain parameters that were established within which the the entire system was forced to operate, whatever genre was involved, there were certain kinds of limits. It’s what I was talking about earlier, trying to get at this aspect of the system earlier, when I talked about the idea of consensus narrative, if the Hollywood film is reaching out to the whole of the society, and it’s telling, essentially a story that appeals to or is supposed to embody the consensus view, the largest general view of, of what the belief system of the of the society is, what that means is that there are limits very sharp constraints, political and moral constraints within which the text operates.

As you know, especially if you’ve been reading your cook, the introduction of a particular sensory system, introduced by Hollywood itself, in order to avoid other kinds of censorship, perhaps from the government, further constrained the kinds of stories that could be could be told, well, within those constraints, of course, as I hope I’ve already begun to show you, in our discussion of screwball comedy, there can be an immense range of of difference, but it’s still within certain controlled parameters. And one of the ways to understand Hitchcock’s immense success is to recognize that he had the kind of sensibility the kind of the kind of artistic impulses, and maybe even the kinds of limitations that made the studio system a kind of perfect environment for him.

Anyone who’s looked at a Hitchcock more than one or two Hitchcock films, is aware of the fact that there’s something obsessional, something deeply disturbing about Hitchcock’s imagination, he’s drawn again and again and again, to the same kinds of situations, to scenes of violence against women, to scenes of confinement, but the studio system was a kind of perfect environment for this kind of, for these kinds of preoccupations. On the one hand, the constraints of the system did not allow Hitchcock even if he had the impulse to do so, to press so far into the perversity and disturbance, that is the general subject matter, he is looking at, as to actually fall into, say, pornography or to fall into something that will deeply offend some segment of the population.

We can see that these were impulses in Hitchcock’s imagination, though, because after the Hitchcock lasted long enough, live for such a long time, he was he was a successful director in the silent era, then he worked in Britain during the sound era and was was was the most well known and successful of all British directors in the early sound era.

Then, in 1940, he came to the United States for what is most people recognize as his American phase, he emigrated to the United States. And and, and that that’s a separate kind of distinct part of his career, as I’ll describe more, in a little more detail in a moment. Well, when he, by the end of his career, hollywood itself was undergoing profound changes for reasons we’ve already begun to talk about in this course, and the most important of them having to do being the advent of television and the way in which through the 1950s, television began to leech away the consensus audience and the consensus function that Hollywood had played in American life.

The effect of this was to, in some sense, liberate Hollywood. And we’ll be talking about what this ambiguous liberation later in the course when we look at some of the great films that emerge in the 1970s that are free of the constraints of a consensus system, films like McCabe and Mrs. Miller, or cabaret, the two, two films that we’re going to be looking at later that embody these, these sort of post studio era ideals and principals.

Well, one of the ways in which you can see the damage that was the, the the help that was given to Hitchcock’s own imagination, by what I’m calling the genius of the system is that at we can see that Hitchcock’s Lee that the latest films that Hitchcock make, the films that Hitchcock makes, at the very end of his career, and especially a film two films, a film called frenzy starring Michael Caine in 1972.

The last film that Hitchcock made in 1976, called Family Plot, the same basic materials. But there’s something gratuitous about the nudity in these, he wasn’t allowed to show nudity in the, in the studio here, and it was good for his imagination. And when his imagination and any any honorable any any honest viewer of Hitchcock watching frenzy, or especially Family Plot, and watching this, there’s a scene in frenzy in which in which a murderer strangles a woman. Now, there have been strangulation is one of Hitchcock’s favorite forms of murder.

There have been many characters strangled in Hitchcock’s movie, but this strangulation has a pornographic dimension to it, that none of the early scenes like that. And it has to do with the fact that Hitchcock is now working in a film environment that is not telling him that he can’t go too far. And he does go too far and there’s a terrible scene in which a man a murderer takes off his tie, and he strangles this woman with a tie. The woman is naked from the waist up and you see her breasts bubbling around on the screen.

While she’s being strangled, and you can see that the camera is enjoying the looking looking at those breasts, even even though it’s a scene of murder, it’s a very, very horrible scene, very disturbing scene, it’s a scene that it almost is a scene that makes you believe in censorship and think that censorship ought to be certainly you wouldn’t want young people to see, the only reason that Hitchcock was free to make to create this scene is that they were no longer the same constraints being imposed upon him by what I want to call the constraining genius of the system.

So my point is that Hitchcock wasn’t a man of obsessional genius of a certain sort. But he had the great good fortune to work within a system that also limited his, his liabilities, that he didn’t even allow the full expression of his obsessions in ways in ways that might that might become deeply disturbing to audiences. The fact of the matter is, when you look at that scene, and then you think back at many earlier Hitchcock movies, you can see many equivalents of it. Violence and damage to women is a recurring obsession, and Hitchcock.

Hitchcock is a sick man in many ways. But he’s not a sick artist. He’s a sick person, he turns his sickness into art, he turns his sickness into us by dramatizing it. And reminding us of the though insofar as he’s a good filmmaker, he’s not a he’s not a horrible perv, right? But, but there are perverted dimensions to his guide.

In fact, part of why we find him interesting is his films are always hovering on the brink of awakening and us feelings that are disturbing and unsettling. And that, that touch on deep taboos in the, in the ways in which our culture sort of understands how we should behave, and especially in our attitudes, toward our attitudes towards sexuality, and, and, and, and, and toward the end towards seeing toward the act of seeing which in Hitchcock becomes a kind of wire ism. So one way to understand Hitchcock is to understand his genius, his greatness as a director as being directly connected to the fact that for the most part of his career, he worked in systems that constrained him, he worked in systems that had very sharp boundaries that didn’t allow him to do certain kinds of things.

Those limitations were turned into artful and, and and valuable gestures, an anecdote that Hitchcock told about himself many times, it’s deeply revealing anecdote. It may not be true, we’re not really sure. But he told it so many times that it’s true, even if it didn’t happen. That’s a line. It’s true. Even if it didn’t happen to line from Ken Keyes, his wonderful novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. And the character that the narrator in the book that was sort of a crazy man, we think he’s in an insane asylum.

He’s in a loony bin, when he starts narrating the story, tells us a story of his confinement in a lunatic asylum. And he says, you think the man who’s saying this is Raven and crazy, oh, my God, this is true, even if it didn’t happen. And what he means is there’s a kind of emotional truth, even if the actual facts aren’t true. And I think that’s true of the Hitchcock anecdote as well. And this is the anecdote he said he he repeatedly told about himself, he said, when he was a young boy, five or six years old, he committed some indiscretion that his father disapproved of, and his father in response without saying anything to the boy, wrote a note, sealed it in an envelope, gave it to the boy and said, told him to take it down to the local Constable, the policemen and in the police station around the corner from where they lived in London.

Oh, the young boy dutifully took the note to them, and they gave it to the constable and constable opened it, read it, and locked the boy in a prison cell and kept him in there for a certain short amount of time. And then finally released him and said, This is what happens to to to bad boys. And his caucus said Ever since then, I have gone to any lengths to avoid arrest, and to avoid confinement in confining spaces. And in fact, if you think about it for a second, over and over again in Hitchcock’s films, the a basic story, not the only story, but a basic story, he tells us the story of someone who is wrongly accused, we might call it the wrong man thing.

Someone who was on the run, who looked at the the circumstantial evidence against him is over or her usually him or his overwhelming, right? Absolutely looks and all the authorities all the legitimate authorities of the culture think that this the protagonist of the Hitchcock case, film is guilty, right. And his obligation is to somehow not only escaped the authorities, who are much more powerful than he of course and have had their back they’re just at their fingertips, all kinds of modern systems for for for folks searching and following and capturing people.

The the fugitive is a lone fugitive on his own without resources, right and without allies. So he’s up against tremendously difficult forces and these are the forces of legitimate authority right? So the theme of the wrong man who’s wrongly accused, the audience knows that he’s wrongly accused. Often, Hitchcock will show the real murder and will and will show us how circumstantially persuasive but also falsely evidence is. So through the most of the movie, we identify with the fugitive with the person who’s running we know he is it, he is innocent.

So what part of it is so many of his films then sort of dramatize a kind of massive principle of injustice that happens again and again, in his movies, authorities are almost always after the wrong man. So and then, and then many of his films and overwhelming an overwhelmingly disturbing recurring element in his films, his confinement in tight spaces, is the sense of being caught. And you’ll see one of the great great instances of this one of his, one of his most artistic accountings of this impulse, is fear of confinement. But this fascination with confined in the great film you’re going to see tonight rear window, which takes place entirely in a single confined space in a room, because the man who the protagonist has a broken leg at the beginning of the film, and he’s literally unable to move out of his apartment. So the entire film is confined there.

Many of Hitchcock’s films love this. So what what an interesting anecdote to be told and think and think, by implication what it says about his father, not not not to mention what it says about Hitchcock himself to have been telling a story like to tell a story like this so many times over the whole of his career. But the idea that a world that seems perfectly benign and protective, could suddenly turn menacing and terrible, that behind any door or window, lurk some monstrosity, that the ordinary world is just a, it’s just an illusion, that what you think of as ordinary and plain and prosaic can suddenly erupt in violence or in terror, or in or in or in the audience, or in some form of unpredictable assault is a constant feeling you have in Hitchcock’s films.

His films, his films dance along an edge in which the whole of the universe could be said to be in some sense, endangered the basic laws of our experience in even even though even sometimes the physical laws of our experience are, are up ended or denied or suspended in Hitchcock’s world.

Can you think of one example where the laws of nature itself, suddenly go cuckoo, one of his most famous films, the birds, of course, the late film, the birds, what happens in the birds? Yes, the most benign and beautiful parts of nature suddenly begin to attack human beings. And then you give some partial explanation in the film where you see there’s a scene in your restaurant, where you see pictures of fried chicken and people talking about how they love roast pheasant, and so forth.

As if that’s an ad, but in all of Hitchcock’s films, there is never an adequate, a truly adequate motive for the madness of terror disorder that is released in the movies. There’s often an attempt to explain that, but nobody takes the explanations very seriously. Because the point is, his vision of life is a vision in which the world is an incredibly dangerous, wholly unpredictable, monstrously fearsome place. Maybe his dominant emotion is the emotion of fear. He dramatize his fear over and over and over again, in his movies.

Here is a brief selection this, he made over 50 films, and I think 53 total films, silent and sound films in his career. This is just the list I’ve put up there. It’s just a very brief selection. But let me say a few things about the the the the trajectory of that career. And then and then I’ll turn to a little bit more about his technical behavior, about his about his technical genius, and about the central themes of his work, which I’ve already begun to elaborate and won’t won’t repeat myself too much, I hope. But let’s let’s talk a bit about his career because he’s a he like the other like, like Howard Hawks and Frank Capra.

Hitchcock is maybe even more than those two, a figure of the a dominant figure of the studio, we are maybe the dominant figure. Certainly the director whose work has been most influential has lasted the longest. One of the most interesting things about his cuts career as a whole is that form, even after film came to be recognized as something more than mere entertainment. Hitchcock was always admired as a great entertainer, and was a successful director from the from from the sound era from the silent era from the time he began to work in Great Britain when he made his move to the United States. In 1939, he was Britain’s most famous and most admired director.

In fact, when he came to the United States, there was a kind of negative reaction in Britain, because because they felt it was unpatriotic of this great director to desert his date of homeland in the middle of the war, among other things, and he did and then he didn’t feel guilt over this in many ways. Some of that guilt is said by some scholars to express itself.

Some aspects of the other feeling you’re going to see this evening. And earlier Phil made in 1943. rut shortly after Hitchcock had come to the United States, it wasn’t his first American film, while he was making that film, he was receiving news from England about his mother who was very ill. And she actually died during the myth while he was in the United States filming shadow of a doubt.

There are some scholars who say that his familial feelings, his guilt over leaving England, his guilt about discerning his mother come out in various ways, in shadow of a doubt, I’m not so sure about that. It’s it’s a pretty cynical and tough minded an anti sentimental film in its own way. But there are some elements of family life in it that perhaps recover or allude to things, aspects of Hitchcock’s own career.

One significant thing, as I’ve already suggested, is that he was successful at every phase of in the history of movies that like hawks, and Capra, he began in the silent era distinguished work, they’re moved into the sound era and to distinguish work in the in the sound here, he has something else in common with hawks and Capra.

I only recently discovered this, it’s not as systematic as in the case of Hawks and Capra, but he too studied engineering. So and there must be something in this, you guys should maybe reconsider what you’re what you’re up to here, because three of the most remarkable and technically adept directors in the history of the students of the studio era, all had partially trained at partial training as engineers. So he begins in the, in the silent era. And in fact, he began, he, lets go behind, let me say just a little bit about his background. He was an outsider in a certain way, even though he was an Englishman, because he was a Jesuit. His parents were Catholic in Protestant England, and he felt himself well, his life, I think, in some ways to be a kind of outsider.

Someone who didn’t exactly fit in, in traditional society, he, he went to work out after his schooling in the advertising department of a Telegraph Company, began to write the title cards for silent films as early as 1921. And then began for this telephone Telegraph Company began to work on uncertain features, feature films that were co produced in Germany. And this is, of course, the great period of German Expressionism, when the great German, silent directors are are creating their science fiction and expressionist works. And Hitchcock in his early life is immersed in that stuff, learns that stuff goes to school in that and you can feel the expressionist impulse in the darkness and the disturbance.

That’s a central part of almost every Hitchcock film. He makes something like, I think, a total of six or seven silent films, of which, of which the Do we have the list up there? Yes, of which the most important is that the pleasure gardens was a co production, the first film that he worked on systematically, and it was a German co production. He wasn’t the prime director and the larger is probably his most almost surely his most important and most Hitchcockian silent film. Can you guess the topic? It’s jack the Ripper. It’s a story. It’s a silent film. It’s a story.

It’s a story about a landlady who thinks fearfully, nervously that she may have rented a room to jack the Ripper, the famous killer so he’s a successful silent director already and admire director makes the transition to sound in fact, historically, he’d be famous just for this one fact blackmail, a British film he made in 1929 is the first British talking. And he almost immediately began to began to figure out how to integrate very interested in all at all the technical aspects of moviemaking, especially interested in the way you integrate sound with image.

As anyone who’s watched the the shower scene in psycho, for example, would be a famous example. Anyone who’s watched these scenes like that, in his cut will recognize the tremendous importance of music in his films, the way he uses music, to deepen uncomplicate and the the the moods he is creating, and especially how we can use mute music to enhance your sense of terror and fear, as he does in certain frenzied, powerful scenes in his most remarkable films.

Then he goes on to a really an immensely successful career as the director of action adventure mystery films, of which I’ve listed the most famous and significant ones films that are still interesting to people that are still watched today for their own intrinsic excitement even though they also many of them also feel a bit old fashioned in their in their behavior. The man who knew too much the 39 steps and the lady vanishes and there are other films he made. In this year, I’m only listing a selection, as I’ve said, then he makes the transition to the United States.

He’s lowered here by David sells Nick, direct the head of a great la studio. Hitchcock is especially drawn to coming to the United States because he envies the technical resources that are available to American directors. So because they have much more budget, they can do much more when they when they have enough when they have enough money to add cameras and to have adequate crews and so forth. And the first film he makes in the United States, Rebecca, a remake of a famous novel won an Academy Award his best film of the year, although Hitchcock did not win a director’s award.

But it’s the least Hitchcockian of all of his films. And perhaps he was restraining himself a little bit in an attempt to establish himself in the American in the American audience. It’s a very interesting film. And you can still see that it in some Broadway fits Hitchcock. It’s a gothic story, the classic English novels about governesses who go to often the country to strange mansions, and there they are both they are both attracted to and repelled by the handsome sometimes scarred, stranger who runs the place, right, I’m talking especially about what novel Jane Eyre, right, Charlotte Bronte his great novel.

That pattern that got that pattern repeats itself again and again in the movies. And Rebecca is a version of that kind of, of that kind of story. And then Hitchcock goes on in the 40s. To make a series of films in which his own interest in the technology of motion pictures and his own obsession with sitting problems for himself that are difficult to solve his own sort of engineers obsession with the technology of Motion Picture begins to become clearer and clearer.

One of the another reason that the largest and important Hitchcock film is that it’s the first film in which Hitchcock himself makes a brief cameo appearance. And after that, it becomes a kind of signature feature of his movies, that at some point in the film, a character Alfred Hitchcock, what will appear briefly won’t be identified, he won’t be noticed in the credits. But as he became more and more well known, audiences began to watch for this act, right that this bothered him in some way, because it meant it distracted them, people from the movies from the movies themselves, because they were waiting to see when hitch would emerge. So he began to do it earlier and earlier in the films in a way in order to avoid distracting audiences.

Think what it means having to devise a way for him to be in the movie. In many cases, it’s easy, okay, a man is getting on a bus so he can be in the crowd. But what happens when he makes films that are arbitrarily restricted as he does in some cases, for example, the film lifeboat in 1944, some of you know about it, it takes place entirely on a lifeboat There are eight or nine characters they’ve they’ve escaped a ship brackets of world war two parable about Nazi ism. And they’re all stuck in the lifeboat and for the entire film.

The film is confined to that lifeboat, it mean it presents all kinds. It’s not one of his best films, but it’s, but the technical challenge presented is really interesting, isn’t it? vertigo is an even more interesting instance. And a much more successful instance of the same desire or the same weird impulse in in Hitchcock himself to create confining situations, and then see what that confinement allows him to do. What what what grows out of these arbitrary these arbitrary limitations, but just as a kind of minor instance of this kind of thing, if all the characters in in lifeboat are on a, on a on a, on a boat in the middle of the ocean? How can Hitchcock appear? Because he’s not one of the main characters?

Does anyone know how he did it? He has, there’s a newspaper lying on the floor of the boat, and you pick up the newspaper. And there’s a picture of Hitchcock in the newspaper. But it’s a trivial thing, right? But it should be and if but it’s it’s triviality is exactly what makes it so interesting. In other words, what Hitchcock loved this kind of problem, when he made when he took these problems in a serious way. And when these problems sort of led him into a kind of exploration of our darker and more disturbed and more uncivilized sides, he made remarkable films that’s that, that are that are memorable, and, and haunting.

One more example of him said of Hitchcock setting himself these difficult technical feats, the film rope, well titled, in a way, it’s a murder mystery. But Hitchcock set it up in a way it’s, it’s actually such that it creates the illusion that the entire film, I don’t remember how long it is, let’s say it’s a standard feature length film, let’s say it’s at nine minutes long. It’s a standard feature length film, it feels as if it’s all unraveled in a single take, as if there are no cuts, no edits in them. Now, it’s not exactly true.

What because that film was not capable, technically, of doing that. What Hitchcock did was he had cassettes of that would that were of film that would last say 10 minutes, so he would make 10 minute long takes, but then you’d have to change the cassette put in a new one, but he’s just Sky’s the takes he disguised the cuts. And in fact, it’s an unbelievably tedious film. And because when you’re watching it, you feel you can’t look away. One of the things that is discussed that you discover when you’re watching this film is that cuts are actually a relaxation.

They let you relax, they they breaks, they break the rhythm in some way. And if you sit there for 89 minutes, watching something that seems to be unfolding them film, of course unfolds in real time. Also, they have, right, so it’s so so he’s playing both with another kind of confinement, which is the duration of the movie, he’s saying, I’m going to make the duration of the viewing the same duration of the action of the movie, and I’m never going to cut or I’m going to create the illusion that there’s not going to be a single edit in my film, when you’re watching it, you actually yourself feel trapped.

You feel you feel guilty if you look away, or you but you constantly want to blink or look down, because there’s so it’s almost as if the absence of edits creates a kind of continuous stream of imagery, and you feel you’re trapped within it like a wall that doesn’t let you escape from it.

Well, that kind, I don’t know that Hitchcock actually intended such a reaction. But it is not inconsistent with Hitchcock’s desire to manipulate your feelings as you’re watching a film. And he became a master at manipulating your reactions as you as you watch the film. So there are many. And I could I could cite many other examples of this sort of technical obsession.

Let me just say a couple of things about the major films in so he and he’s successful in every phase, but he really comes into his own most critics would say, at the end of the 1940s, with a series of making the early 50s, with a series of films that run from 51, through, maybe most people would say, through the birds in 1963. I haven’t listed all the films he made in that era, but I’ve listed the most important ones.

If you can judge for yourself how significant this is why? Because look at how many titles you recognize how many titles by directors of so many years ago, would you actually have seen, it’s one measure of what an important figure what a successful figure Hitchcock is that that he’s still so widely known that he’s more famous today than he was when he was making his movies.

I started to say earlier, one of the most distinctive things, or interesting and revealing things about Hitchcock’s career is that through the through the massive his career, even though he was one of the most popular directors at his films, made money and he was he was a totally bankable director noted that maybe the most bankable director in Hollywood during the studio era, he didn’t get much respect. Part some people have have suggested that one of the reasons for is that he gave so much pleasure, that there was a feeling that anyone who gave this much pleasure couldn’t be an artist.

That that it worked against him that he would that he was such a great entertainer. And there may be something to that, but steadily over time, and especially since his death, his reputation has increased and increased and increased. And in fact, recently, his film vertigo was voted the best film of all time the best film ever made, displacing Orson Welles, the Citizen Kane, which had been at the top of this list for something like 20 years.

This Ascension from in which Hitchcock was sort of denigrated as a mere entertainer to now being recognized as one of the greatest artists of in the movies of the 20th century is a very interesting development. And it’s a development that’s partly a function of the fact that all of that happened after the movies were no longer the central experience in, in, in America, the central narrative experience in in the modern world in which they already been displaced, as a as a as a system. So in this period between the Strangers on a Train through the birds in 1963, he was some people might include mourning, in 64, he made a series of masterpieces that are among the most significant and most powerful films ever made. Two of which we’re talking about tonight.

Hitchcock the technician. I’ve already implied something about this. But it’s worth emphasizing this Hitchcock because Hitchcock became famous, especially in the industry, for the unbelievably fastidious, almost bored way in which he carried out his direction of the movie. By the time Hitchcock got to the set of the film, he had so obsessively planned out every aspect of the movie, that that he acted as if everything was all finished his enemy and he he often annoyed his actors, some actors disliked him a lot because he gave very little instruction to his actors.

Some actors like this, but many many resented in a great deal. He said he is often quoted as as he’s been quoted a number of times as showing a kind of disregard for actors. At one point he said actors are just capital. To be moved around on the set like animals, but but it was more of the fact that the actors had trouble with him, because he seemed to have worked everything out before he got to the set, he was always tremendously calm, he sat in his director’s chair would give directions, and he had storyboarded, he had drawn out every single scene and every single camera angle before he even came to the set.

So that it was as if he had worked everything out before he reached the set. And, and what that meant, of course, is that no improvisation on the set, he would be very unhappy if people tried to deviate, never allowed people to deviate from the plans that had been set before.

This is in shocking contrast to the, to the way in which let’s say a director like genre, Anwar or sometimes Orson Welles might operate in making their from quite the looking for the contingent and the accidental that happens while you’re at work creatively, Hitchcock would have none of that. Hitchcock came into the process of directing, with the film finished, completed in his head, completely, fastidiously blocked, angled, and so forth, and there was no deviation from it.

He actually did often act bored when he did it. But how interesting that is, so he, but he’s also of course, a supreme technician of the movies, a master of camera angle, a master of montage, a master of the mingling of of music and image, right? And, and, and you’ll see many, many examples of this in the two films you’re going to see this evening. How interesting then that he is this incredibly fastidious, granular technician, who plans out every single camera angle before he comes on the set. What does this tell us? Why would he do that? What’s interesting about it, what’s most revealing about it?

Why would someone do this? Maybe if the subject matter you’re trying to deal with is so unruly and so frightening, that the only way you could handle it is by surrounding it with this pretense of fastidious coherence and control. And I think that there’s no question at all, that his cool demeanor, his mocking demeanor, and especially his sense, when it comes to make the actual make the film to actually make the film that all the problems have been solved, that everything has already been done is an attempt to compensate for or defend himself against the roiling irrational power of the subject matter that his films mobilize.

What a wonderful revealing paradox, right? He’s this fastidious technician. And he’s, but his themes are the themes of craziness of madness, of murder, of wire ism, of violence, of rape, of strangulation, of fear, of pursuit, imprisonment, confinement, injustice, one of the most interesting things about Hitchcock. And those of you have seen more than two or three of his films will feel this much more strongly than those of you who’ve only seen a few of them is how over how, essentially passive deeply and aggressive and acted upon most of his protagonists are. They’re being pursued, they’re on the run.

They’re confined in small places. They’re full of fear. One of Hitchcock’s recurring moments, a recurring scene is, is the protagonist dangling from a height, you’ll see one magnificent instance of this at the end of rear window where Jimmy Stewart is hanging like this above avoid, you see his face, and you can see his face register abject fear, right? We could call that one of Hitchcock’s iconic moments, it occurs again and again, in his movies, characters hanging over a void, terrified, terrified of what of what of what is about to happen, and often they fall into the void their image. And some of the dream sequences in Hitchcock are show us characters falling through voids into nothingness. So the subject matter of Hitchcock’s films, couldn’t be more shocking and disturbing. In some sense.

They mobilize problematic subjects that are terrifying. And they obviously were so terrifying to Hitchcock that his only way of dealing with them was to surround them with all this appearance of control. Another thing that follows from this, and it’s a very one final point to make about Hitchcock’s films is how often his reassuring are happy endings don’t reassure or make us happy.

And the reason, of course, is that he doesn’t mean the happy endings. I’ll come back to this again. But very often he even though his films fit them perfectly within that with all in perfectly but well enough into the convention, that the endings of a in a consensus system that the endings of these stories have to in some sense, restore normality and reassure us Hitchcock goes through the motions of doing that, but again, and again the endings of his films are morally ambiguous and, and provide us with kind of subtext which put in question, the reassurance that we have superficially been offered, as if there’s a kind of, as if there’s a level of, of irony and cynicism, and deconstructive contempt beneath, undermining the reassurance that the endings that the endings offer us.

That’s also a part of this, of this idea that the themes that that Hitchcock mobilizes are the are the are the dark elements of our subconscious and of our unconscious and of the and, and the fear that people have fear of authority, fear of disorder, fear of disturbance, a sense that the ordinary world is full of menace, and terror. But again, and again in Hitchcock’s films, he doubles his characters, and you’ll have a good character in the evil character, the idea, he grew up in the era of Robert Louis, steeped in the late Victorian era of Robert Louis Stevenson, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. And he actually thought that was a version of human psychology that there’s a kind of dark or savage aspect in ourselves that’s hidden or damped down by civilization.

If we, if we let it come out, we could turn monsters we could turn horrible, right? And, and again, and again, in Hitchcock’s films, we have a kind of doubling in which one character interacts with with a more villainous or murderous character who come who we come to recognize as a kind of double of the protagonist, or represents the darker, more disturbing energies within the protagonists. Nature, right. And in Strangers on a Train, what happens a guy pops up, a tennis star, who’s having trouble with his wife is on a train, and a guy pops up next to him and says, I know you’re having trouble with your wife, I read about in the newspaper, let’s make a deal.

Nobody can track us. It’ll be the perfect murder, I’m having trouble with my wife, you murder my wife, and I’ll murder yours. Then the guy said would get a Get thee behind me, Satan, right? Don’t ever talk to me again.

I’m very nervous about a few weeks later, his wife is murdered. And then he starts getting messages from this guy, when are you going to fulfill your part of the bargain, right? That’s what the film is about, right. But it’s a wonderful, interesting movie. The thing I want you to see now dramatize is some of this. And this is it comes at the end of the film at the great climax of the film. And one reason I want you to see it is that it also shows another aspect, another aspect of his what we might call sort of the world of the thematic world of Hitchcock’s films. And it’s his it’s his recurring interest in the subject of entertainment itself.

What he became aware of, and what his films often dramatize, is the illicit and disturbing dimension of our desire to go to the movies, or have our desire to have the kinds of excitements we get when we go to amusement parks. What Hitchcock understood was that these experiences have an illicit dimension, we sit in the dark, and what do we do when we sit in the dark, we watch people take their clothes off, we watch the murder each other, we’re sick, we’re in the dark, we’re safe. Nobody knows.

We’re Solitaire, we’re anonymous. But we’re what our wires were, what he understood was that wire ism was at the heart of going to the movies was not the heart of the movie experience. And if they will, we’ll come back to this, we’ll come back to this scene. So So at the end of Strangers on a Train, there’s a particularly wonderful and dramatic example of Hitchcock looking at the space of entertainment, as a space that can turn into an environment of menace and disturbance.

This his character. And and again, exactly because he’s Remember I said one of his deep themes is what might we might call the menace of the ordinary, well, what could be more ordinary and reassuring than a child’s merry go round? Here’s the great climax of Strangers on a Train in which the good and the bad, the good and the evil sides have to do engage in a kind of contest or wrestling match. And as you’re watching, note, the way in which characteristic of Hitchcock characteristic of him, there’s a combination of terror and comedy. He unsettles us also because the most often the most terrifying scenes are leavened with a kind of mccobb comedy that unsettles us even more. Here’s the seat.

Good guy, bad guy, he finally sees his problem. These are very helpful FBI people who do more harm than good. They shoot at the wrong person to begin with and they actually accidentally shoot the person who’s controlling the merry go round so it goes out of control.

Part of the comedy here is they’re wrong. They don’t know who they’re talking about. They have the wrong man, but we in the audience know it. Be able to do it yourself.

She only gets such confidence that he could introduce a comic moment like that in the middle of what is a terrifying climax, the only director would do that regularly.

Now you know who the bad guy is, right? So the hero rescues the kid. So my title reviews on Santa Fe, a montage effect, right? See the close up on the animal, the way, the way you get very, the camera itself doesn’t allow you to sort of look back and get a sense of the environment, your your emotions are controlled by the tightness of the shot by the quickness of the editing.

Comic version of a hero, right? And this is quintessential Hitchcock. Are we saved? Very helpful. All right, that’s, you get the idea. So the fact the fact that this space of entertainment, that you get lights up the fact that this space of entertainment could become a space, one more minute people could become a space of terror is the point. So finally, what would we say about Hitchcock?

He’s a double man, to borrow from the great essayist muntanya. Who said, I, we are we human beings are I know not how doubling ourselves, so that what we believe, we disbelieve, and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn, what Hitchcock tries to condemn, or what Hitchcock thinks he hates, keeps coming back in his films. Images of strangulation, of damage to women of images of fear and, and, and terror in the face of irrational authority. These key these themes keep returning again and again in this film with the power of obsession, but he controls the obsession with that fastidious tactical distance that allows these obsessions to reach us in a way that disturbs and enlightens.

Transcript: 96-Minute ‘Masterclass’ Interview with Alfred Hitchcock on Filmmaking

Interviewer 0:15

Good morning, and welcome to The Family Plot Follies. We’re, I am particularly pleased to be here. As some of you know, I’m sometimes what I like to think of as a critic. But I’m here less than my critical capacity than as a sometim. biographer, friend and longtime admirer of Alfred Hitchcock and his art. I can’t resist the kind of a brief critical comment, which is that it seems to me that this film is Hitchin, one of his most entertaining moods. And yet, it seems to me also a film that takes up as his films invariably do certain themes that have been repeated in his life and in his career, almost from the very beginning. But to begin to hit China, kind of a practical note, I’m sure everyone would like to know how long it takes you to prepare and shoot and get ready for distribution of film of the sort.

Alfred Hitchcock 1:27

Object before I answer that, I have to go back to your original comment. And that is about one doing similar themes all through one’s career. I believe it was someone who said that self plagiarism is tile. So just this particular job just completed, took about a total of two years. That was one year in the writing. And why you may ask why so long as a year. I think most of the time was spent trying to avoid the cliche. Because invariably, one worker said, Oh, this has been done before. So ideas did not flow as freely as one would like. And it was the effort to get something a little different. You know, crime is a crime, whichever way you commit it. Whether it’s a murder, kidnapping, what have you. you’re faced with that. The question is, it’s like writing the C, wave, say, Man comes through the door. But the big question is How?

Interviewer 3:19

I think you’ve said on a number of occasions that it’s important to you to be extraordinarily detailed, especially in terms of the visual aspects of a film on paper, before you ever get to the shooting stage.

Alfred Hitchcock 3:38

Well, people often ask this question. And I say, I’ve made it a practice over the years, many years to put a film down on paper. You see, people say to me, don’t you ever improvise on the set while you are shooting? And I say, certainly not. All those electricians around and everything. I would prefer to improvise in the office. And cheaper anyways, and cheaper and quieter. And after all, musicians are allowed to put their composition down on paper. And architects can put a building on paper. So why not film? It’s a visual thing. So mere description of the film on paper should suffice. I think the drawback with a lot of people suffer from is the difficulty in visualizing something you see You can’t, it’s no good for a Motion Picture, putting down on paper, he wondered, because how do you photograph one? So what what goes on paper is a description, going back to five said, how he came through the door on his face, knees or what

Interviewer 5:26

it does seem in this morning’s paper, one of the stars in the picture, Bruce Stern, is quoted as saying that, in fact, he found it very happy working with you that he finally had a lot of room himself in his performance, to go in directions, that, that he felt appropriate to his character that you were not restrictive in that sense.

Alfred Hitchcock 5:52

Well, I’m not as a matter of fact, I have had occasions with accesses, for example, who came to me extremely cheerful, and complaining they weren’t being directed. So I said, Well, I don’t read this script, we put the film down on paper, the only thing I have to do with you, is to tell you when you are doing it wrong.

Unknown Speaker 6:33

And and some of them can get in very, very intense. And mastering the entire remember, Ingrid Bergman used to get very worked up and say, Oh, I don’t know what to do here and so forth. And I used to say to Ingrid, it’s only a movie.

Interviewer 7:07

Well, this is only a television broadcast. But nonetheless, we have a lot of people out here with I imagine a number of questions. So I would like to open the floor here in Los Angeles, at least for questions. Right here for

Bruce Russell, of Reuters news agency. What is the mandatory retirement age for a director in Hollywood? I would say real well. Be told the lady right here.

The Australian consolidated press. Mr. Hitchcock, you’ve introduced many new faces to the screen. What do you look for when you’re searching for before?

Alfred Hitchcock 7:59

Well, it depends upon the character. You know, of course, in the old days, and are now going back to the 20s. The leading man had to be handsome, well groomed, dapper. The woman had to be a blonde, floppy blonde. And these were more or less stock characters. But of course today that isn’t so 110. Right. Didn’t Family Plot. Go for characters? purely characters?

Interviewer 8:47

Gentlemen, back here. stormlight archive. I’m San Francisco Examiner, Mr. Hitchcock. This firm has a great deal less violence, it seems to me than any of your others. As a matter of fact, there seems to bethe numbers move in the other direction. The one death in the film is accidental. There is no real violence in the film. I wondered if this was deliberate and why?

Alfred Hitchcock 9:16

I don’t I’ve never been a believer in violence. For example, when I when I made the film psycho, I deliberately made it in black and white, to avoid showing blood running down about I’ve never been one for violence. And this is a story called for it. Showing blood. You know, there’s nothing to it is just photography of blood. It doesn’t necessarily contribute cinematically to what the scene is about. So therefore, I’ve at least enjoyed be avoided. What about the absence of bodies? Here is where I’m at the absence of death and bodies in this in this film as compared bought you mean? nudity? No. You mean dead Bob? noodles? Well, don’t walk them. They don’t know, a dead body doesn’t that?

Interviewer 10:31

I think though there is a feeling perhaps just in contrast to your previous film friends here, which, after all does deal with a psychopath that I think is possible. And what the gentleman is getting at is that, in contrast, this is a film in which all violence is in a sense of violence of the mind. And perhaps you did deliberately veer away from the psychopathic theme to the rather clean, jewel theft kind of thing.

Alfred Hitchcock 11:08

That’s true. On the other hand, you see, the wharf kidnapping, and the kidnapping was done. with as much decorum as possible. Mr. Hitchcock since you brought up the subject of kidnapping, Do you sometimes feel that there really isn’t much room left for suspense film when you have events like this morning’s paper, kamikaze pilot trying to kill a Japanese financier or the Patty Hearst kidnapping? Is it sometimes Do you sometimes feel that real events have outpaced what you could possibly dream of in a suspense movie? Well as suspense movie, at least from my point of view, is giving the audience information in advance. Not after the fact. You see, there’s a great deal of difference between giving the audience the anticipation as again, surprising them. A surprise takes 10 seconds. But anticipation can take an hour as a big difference. But most people, you know, they made mystery films, which I don’t I call them mystifying film.

Interviewer 12:32

Yes, but you don’t you’re not really answering my question. I wondered if sometimes you feel that the real life dramas have sort of outpaced the film’s possibility of exceeding that or even giving the equivalent of that? No,

she’s saying world is such a violent and disturbing place. Is it difficult for you now?

Alfred Hitchcock 12:52

Yes, because we’re fighting headlines all the time.

Interviewer 12:56

To the degree this question raised the question in my mind, it seems to me the crime of our current time is in fact, kidnapping. There’s been an enormous Yeah. But is that to a degree? Is that in any way influenced your choice of the kidnapping theme? Or is it certainly something that filters into your mind? And no,

Alfred Hitchcock 13:17

I didn’t want I didn’t say, I’d like to do a kidnapping film. What what interested me about a story like family plot was that it was two sides of a triangle missing at a certain point. In other words, you say you started at the bottom, it was like a triangle without a base. And gradually, they apparently had no association, whatever. And as they came to their apex, that was the shape of the film. And the climax, the apex came when these two totally unrelated elements came together. And they came together, just as the leading lady rings, the front doorbell of the house, which contains a kidnapped bishop. And that’s what appealed to me was the structure of this story. And the kidnapping and all those elements were, you know, part of it, but certainly no great inspiration to me.

Interviewer 14:40

But the plot was, are you have you ever done a film with a structure at all similar to this? No, this is the first time Yes, gentlemen, right here. Craig McDonnell from lafer Publishing Company. Directors such as Francis Francoise Truffaut, and Brian dipalma. have made films that have been Hitchcock like films I wanted. That’s what the critics have called them. I want to know if you happen to have seen any of these directors films and what you may think of the influence you’ve had on directors.

Alfred Hitchcock 15:16

I’ve seen the film, but I can’t honestly say that I can see myself or one’s technique in. I think the one thing that Truffaut told me once, what he had learned from me, was the subjective treatment. In other words, a given example, what about subjective treatment is a picture like real window, you get a close up of a man, you cut to what he sees, and you cut back to his reaction. And the whole structure of that film was done on those lines, not a word, you use a camera. Or as the person who sees something, it’s a definite three piece structure. And that’s what Truffaut have learned, you see, it’s like, it’s like, when you see films of automobile crashes, the audience are on the sidewalk, they’re never involved. Now in Family Plot, you are entirely with the audience with the couple in a car, that is lost control. And the whole sequence is composed of close ups of the people and the road ahead. In fact, I took a step further than they usually do. In those sorts of scenes. I didn’t even include the dash, or the window frame or anything. I just dropped close ups of the people and the road ahead, which was the motion they were feeling our photographing an emotion, not a viewpoint. So that was a step beyond the rear window concept. Yes, well, that lady. Oh, I’m sorry, this lady. Yes.

Interviewer 17:21

I’m Nancy Anderson, with McFadden magazines and coffee News Service. But I’m also a grandmother of seven. And I think it’s in this capacity, I want to ask a question, because there’s so little violence in the picture. And it’s such good suspenseful at a time. And it would be great for family groups, except for some of the very body and blasphemous dialogue here on the air. And has there been any thought of editing any of that outgoing speech or general audience appeal?

Alfred Hitchcock 17:51

Not so far. The people speak contemporaneously, you know, if you eliminated that, I think he will cut down some of the quality of character in the two people.

Interviewer 18:12

Mike Callahan, National Catholic reporter destructure, it seems to me or apparently comes from the original novel. And I was curious in your adaptation, one thing is to kind of visualize it, the kind of thing you’re describing, but do you want adopting from another medium? Do you make large changes in the, in the original medium? And how do you do ever consciously you kind of put in Hitchcock themes or touches to original, twice, perhaps, and never look at it again. And start from scratch. Because if you look at a book, and you try to translate it, it’s very hard to do good literature does not make good pictures. That’s been shown again and again. I think we have time for this gentleman right here. James Mead, San Diego union, you were a very heavy user of coincidence. And I wonder if you feel it coincidence, actually does influence human lives in reality, or it’s a fictional person’s device to to make things progress either in writing or in filming, and so forth. I think coincidence belongs to ordinary life. There’s a phrase very often used in coincidence, which says, Fancy meeting you of all people.

Good morning, my name is Richard J and overlay. And I was wondering during the production of family plant, you had an implant operation for a pacemaker. When you return to work, did you find that this altered your normal work pattern? Or did you look at the film or your subject matter different?

Alfred Hitchcock 20:19

whatsoever? I’m not even aware that it’s there.

Interviewer 20:23

Fabulous. Time for one more this gentleman here, Tony price or UCLA daily Bruin, I might go back to that car chase for a moment. At what point did you

Unknown Speaker 20:33

decide to have the emphasis more on the humor than the terror or the potential terror and that scene,

Alfred Hitchcock 20:40

I think the humor emerged through the players actually, is a very fine line between humor and tragedy. But really what that car chase did, it combined both elements danger, humor, and the thrill of the thing.

Interviewer 21:12

I think it’s time now for us to go to the first of the cities. For those of you who didn’t get a chance in this first go round here in Burbank. We will be coming back here for more questions from you, as we will from the other cities. But at this point, I’d like to call upon Jerry Evans in New York, who has arranged his questions, I’m sure. extraordinarily intelligent order. Jerry. Good morning. And could we have your first question? Are you there? I noticed that you and I just celebrated your 50th anniversary. I hope that helps. I were having a little trouble hearing the questions up here on the stage. But as I picked it up, they’re asking if you have another picture in in the works at this point.

Alfred Hitchcock 22:13

Now the answer is definitely not. Not at all.

Interviewer 22:18

Well, perhaps I could ask you, is the process one of slow gestation? Or how is it that you go about seeking out material of your sort and come

Alfred Hitchcock 22:29

from all it comes through literary agents? It comes through book reviews from various countries that our family plot was an English book originally. One thing we never do, we never actually take material direct from a writer. It’s too dangerous if it arrives in an envelope that by that we feel it we wait. Not to get a quality of the material inside. But the fear of plagiarism is the last digress to tell your story of a local actor, an actor called English one called power the best he played in the film with Michael Caine called out fee. And he was a little Cockney type. And he was in a group of three and he was a little too short. So somebody sent for a script for him to stand on and raise him up. The camera man was very, very slow. And finally little Alfie bash said, Who wrote this script? He doesn’t have Berkshire feet.

Interviewer 24:15

Jerry, do we have another question from New York? Or we’re moving I see we’re moving on to Chicago. And to Mike Kaplan. Hello, Chicago. Are you there? And can we hear you?

Unknown Speaker 24:34

Hello, Mr. Hitchcock. This is our scene of the Milwaukee Sentinel. Getting away from the film, per se you have a reputation for being quite a practical joker in your own part. I wonder if you might tell us what was the best practical joke ever played on you?

Alfred Hitchcock 24:56

on me, no one would dare now The best practical joke one of the best I ever made was to give a dinner where all the food was blue. And having Gertrude Lawrence was one of the guests. He was in a private room above a London hotel, also. So Gerald Omari, who was the leading actor on the London stage, and we started off with blue cream soup, blue trout, blue chicken. And then we had blue peaches with blue ice cream. Refresh success.

Unknown Speaker 25:53

Do we have another question from Chicago? Christina on Chicago Daily News. Did you consider any different endings for the film? It seems to me that there was that huge inheritance sitting there with Kathleen Nesbitt. And did you ever think about maybe Bruce Dern posing as as the son himself and making up with the money?

Alfred Hitchcock 26:12

No, never did never thought about any other ending except the one that we have in the picture? Because there’s no drama and money match? Only if you don’t have it. Is there another question from Chicago?

Interviewer 26:37

Jean Cisco from the Chicago Tribune. Right now, in the movie industry, it seems that violent pictures, sell day in and day out the best. I’m wondering how that makes you feel about the profession that you’ve given your life too. I’m wondering if you’re very optimistic about the future of the movie business? And if so, can you point to either people or trends that make you optimistic?

Alfred Hitchcock 26:59

Well, of course, as you know, we’re going to have changes in the future. some extent on gather, there’ll be a certain amount of how movies through the use of disk of vision. But, you know, many years ago, I attended a new Herald Tribune forum, in front of about 300 school teachers. And this was when television was first started. And I was asked that I think television would affect the theaters. I said it might be a little. But on the other hand, the thing is, that is really going to be affected is the cloak and suit business. Because women will want to go out with a new dress on and reminds me of those pictures, which I call sink to sink pictures. The husband comes home and he finds himself confronting his wife who is washing dishes as a sink, and he takes compassion on her. Take off your apron, put a nice dress on, we’ll get a babysitter, we’ll go out have dinner, and take in the movie. And she’s overjoyed of the prospect of getting out of the house. So they parked eventually get to set apart a car, I had dinner, and they sit in the movie house, and the wife looks at the screen. And what does she see a woman washing dishes at the scent?

Interviewer 28:57

I take it you think there’s very little future in that line of work? Wow.

Alfred Hitchcock 29:03

I think people will want to go out. Otherwise it means that if it’s if they’re going to stay at home all the time, then you’re gonna have a revolt or by by the why. Do we have another question from out in the Middle West?

Unknown Speaker 29:20

on that question, what about the quality of filmmaking? I was trying to suggest that it seems that we’re getting into very crude, broad, violent strokes with sharks biting people, things blowing up fire spreading and none of the subtlety that you were talking about gave you so much pleasure in making this film. Other people that you see working either young or old people working with give you the kind of optimism Are we going to just get blown away with big action pictures?

Alfred Hitchcock 29:49

No, I think big action pictures have their day. We always had them for the last 20 or 30 years and We shall shall have them intermingled with the more intimate picture. Another question,

Unknown Speaker 30:11

I guess the calorie for winter, what is that? I noticed in this movie that there was more symbolism than usual like with a name rainbird. And shoe bridge and Blanche, and the two kidnapping victims were like one was the bishop and the other was the Greek Constantine. And I wondered how much of the symbolism you intentionally kept in there, how much was from the bullet car? How you feel about that?

Alfred Hitchcock 30:39

I don’t think that symbolism meant a lot to this story. They just happened to be names. And types really don’t look rarely for symbolism any more than I look for messages in a film, wasn’t it Samuel Goldwyn, who once said, messages off of Western Union.

Interviewer 31:09

It is true, though, hits really from, it seems to me the beginning of your career in film, that, in particular, religious symbols have played a part in a rather subtle way in.

Alfred Hitchcock 31:26

In your films, that may be true. But I don’t think in a very, very conscious way.

Interviewer 31:37

Well, one notices, for example, in this film, the business of the abduction of the bishop, right from a place of normally we think of as the most secure and the places that we can possibly go That is to say, a church is that we understand that disorder can intrude into even sacred places.

Alfred Hitchcock 32:03

Definitely, yes, I would, I would regard that as a piece of CounterPoint. Really? Could you explain that a little bit? Well, you know, of all places to go would be to a cathedral, just as much as you might have murder in a theater, which you’ve done a few times? Yes. Again, it’s an effort to avoid the cliche. You see, for example, in that film North by Northwest, I had a situation where Cary Grant was supposed to be put, quote on the spot. And what was the cliche the cliche was that he would stand under a lamp on an intersection, bathed in a pool of light from the lamppost. Then you cut through a black cat sliver in by, then you’ve cut through a window, and the curtains were pop, and somebody would appear out? He would be midnight, this clock would chime. So I decided this is all cliche. I’m going to do it in the open air in the bright sun will nowhere for him to shelter, and apparently no place from which the assassin would turn up. So I chose flat, open country. And where does the assassin come from out of the sky. Now, all that was done to avoid the cliche. And not only that, the the attack was contrapuntal by the use of the crop duster. Now, another important point is if you use a crop duster, it must dust crops. So he went to hide in a cornfield, and the crop duster came over and drove him out in front of a road. So there was an example of doing an attempted murder in very unconventional surroundings. Right. Have another question, please.

Unknown Speaker 34:34

Mr. Hitchcock, Roger Ebert from the Chicago Sun Times. The other day, I got a call from a graduate student who’s doing a paper on the use of the staircase as a motif in the films of Hitchcock. I suggested that she write to you. How would you respond to a question like that or to academic criticism in general?

Alfred Hitchcock 34:52

I think the staircases are made to go up and down And therefore, they become very photogenic. But they that they rise, they take a finger up and down. Instead of keeping a finger on the flat, I suppose the most famous staircase I ever used was her film I made in 19. Hold on to your breath 26 and there ever was a film about jack the Ripper and jack the Ripper have to go out at night about 2am and the landlady of the rooming house in wiki live, sat up in bed and listened. And I had a staircase bill for flights I and we had to photograph her from the studio roof. Looking down the well. You saw the continuous hand rail, and just a white hand sliding down the hallway. Of course, today with sound we would do Creek from the stairs. But that was the most valuable use of a staircase under those need for condition. Another question,

Unknown Speaker 36:21

Indiana post Tribune, Mr. Hitchcock, I enjoyed the film very much. But I noticed one thing that seems all by itself separated from the rest of the film. And that was the second scene in the cemetery, when the camera came away, and you saw them like working their way through a main. And it seemed rather a romantic kind of image that you had created. Is there any particular reason for it?

Alfred Hitchcock 36:48

No one had a practical value. It showed a kind of a chase. And I was possibly influenced by the paintings of Mondrian, which are a series of lines, straight lines converging into various squares and turns. And I felt it was just a fresh way of doing the small Chase. Instead of just cutting from one period to another, or cut into the feet. It was a more spectacular way. But nevertheless, its purpose was to show that our hero was getting nearer and nearer to his goal, which was the woman

Interviewer 37:39

also thought what was rather witty about that scene was the fact that he never left the path that he was on. He could have cut cross lots, as it were, and did not the notion of staying in the past. That was kind of humorous,

Alfred Hitchcock 37:52

as well, it was it was humorous to the extent that you do try and preserve in the cemetery, some decorum. Exactly. So is there another question? Charles calorie,

Unknown Speaker 38:09

Fort Wayne, Indiana journal Gazette, you mentioned that you don’t intentionally go in for symbolism those that would be say in the names quite a bit of symbolism on the part of the writers such as Adamson’s name, the son of Adam and the good and bad symbolism and you did put Blanche for example, in a white car, which goes along with the good angle there was that intentionally or how did that just add? Gotcha now hitch,

Alfred Hitchcock 38:33

the white car was definitely huge to let the audience know, whose car it was one of the things I make mistakes in film, they get an audience confused, they make an order in say now when when, when when which has is what these have got to be identified. And if you’re going to get suspense, you got to make everything very clear to an audience especially where the diamond was hidden in the house, I had to make that if I may say so. crystal clear. An audience wondering is not an audience emotion. That is why the clothing or the types of people you use must be extremely distinctive, so that the audience know who is who. And they must not wonder they must not Naji, Java in this data And get confused. I had a very interesting story showing audience confusion where one of my assistants went to see a performance of a musical, Sweet Charity. And in intermission when the lights went up behind her were two women with their husbands. And one woman said to the other, oh, I do like, Don’t Q. And the other woman said, well, I’ve always liked Barbra Streisand. So one of the men said, What are you talking about? Bob Ross Streisand in Funny Girl. So we have a woman said, Well, this is funny girl, isn’t it? That’s a confusion.

Interviewer 41:10

We’re gonna try and solve some earlier confusion. Apparently, the line to New York is now open. So we will leave Chicago briefly, and try once again to get in touch with my colleagues in New York. And with Jerry Evans. Do we have a question from New York?

We are awfully sorry, New York. We still can’t hear you. And we’re going to keep working on that. We will now however, go to Dallas to Bill Burton, who is organizing our sounds down there. Bill, do we have a question? from Dallas?

Unknown Speaker 42:03

Yeah. Don sacnas, Dallas times Herald, Hitchcock and you referenced before to self plagiarism? At what point is it cease being style and become a cliche?

Alfred Hitchcock 42:17

Well, the cliche belongs to anyone except me. Well, there’s a brief answer. Next question. Mr.

Unknown Speaker 42:38

Hitchcock, Patrick tankard of the Austin, Texas American statesman. You perhaps more than any director I’ve seen lately hard, generous to women, both in the number of roles you give to them and in the kind of parks they play. Is this a conscious effort of yours? Or is this just part of a being Alfred Hitchcock?

Alfred Hitchcock 42:59

Well, do you know the use of women in pictures is historical, and inevitable? I’ve often been accused of using cool blonde women. I think this is because I personally, on the screen, have an objection to the type of woman who wears has sex, ran her net like jury. Great big baubles, I think they would be cold. And I don’t think it’s interesting to label or put a label on a woman and say, Oh, she’s sexy. I think it has to be discovered. Whether the woman who can look like a beak, he knows schoolteacher. And y’all eventually discover it when you are both alone in a taxi. But otherwise, I think that the the women should be discovered in the course of the story. The cool blonde type, I think, come from Northern Europe, Scandinavians, the Scottish the English, the Norwegians, and perhaps North Germany. The further south you go in Europe, the more obvious they are. I won’t go so far as to say they are obvious enough to walk around carrying a rose by stem in her mouth but I think sex should be discovered in the course of the story. You can’t walk along the street, walk along New York in Fifth Avenue and point to every type, you see and say, Well, she’s sexy. She’s not sexy, or is it has got to be found out? I mean, that’s part of storytelling.

Interviewer 45:26

One thing that does occur to me is that perhaps what the gentleman was referring to is, there’s been a lot of talk of late that there or not, or have not been as many good roles for women in films in recent years, as there has been in past years. And which leads me to point to, which is that there’s very good role for a very good actress and Family Plot, namely, Barbara Harris. Yeah. And I thought perhaps you might want to comment first on the general point. And then on the more specific point of barbers performance.

Alfred Hitchcock 45:56