During the waning years of 1950’s England, a group of documentarians arose to address pressing concerns, including poverty as seen through the eyes of working class citizens.

The movement was dubbed The Free Cinema (1956-1959).

Many Free Cinema movement filmmakers began as writers writers for leading film related publications, most notably Sequence and Sight & Sound.

These filmmakers were the polar opposite of the previous British documentary movement which was much more wistful and nostalgic, and seemed to be more propaganda than anything else. The Free Cinema movement was committed to documenting the realities of England’s working class.

Free Cinema Manfiesto

The Free Cinema Movement’s Manifesto was created by Lindsay Anderson and Lorenza Mazzetti at a cafe in Charing Cross called “The Soup Kitchen”.

Here’s the basic text:

“These films were not made together; nor with the idea of showing them together, we felt they had an attitude in common. Implicit in this attitude is a belief in freedom, in the importance of people, and the significance of the everyday.”

They go on to say:

“As filmmakers we believe that no film can be too personal. The image speaks. Sound amplifies and comments. Size is irrelevant. Perfection is not an aim. An attitude means a style. A style means an attitude.”

The Free Part

The free in Free Cinema refers to the fact that the films were made on the cheap, made outside the studio system, and were singular in terms of their style, attitude, and production values. They were usually shot in black and white on 16mm film using hand-held cameras. They also stayed away from the Voice of God narration of the previous movement.

The British Film Institute’s Experimental Film Fund provided most of the funding for the films. Ford Motor Company funded some of the later films. Most of the films did not have narration. The film-makers wanted to focus on ordinary, working-class British subjects.

The people felt that they had been overlooked by the film industry. The Documentary Film Movement of the 1930s and 1940s, which was associated with John Grierson, was dismissed by the movement’s founding fathers. Jean Vigo was acknowledged as an influence. Free Cinema is similar to the cinéma vérité and direct cinema movements.

Notable Directors

Notable Free Cinema documentarians included:

- Lindsay Anderson

- Karel Reisz

- Tony Richardson,

- Gavin Lambert

- Lorenza Mazzetti

While they were the central figures of the movement, others came on board later as well, including Robert vas, Michael Grigsby, Claude Goretta, and Alain Tanner.

Want to watch more short films by legendary filmmakers?

Our collection has short films by Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, the Coen Brothers, Chris Nolan, Tim Burton, Steven Spielberg & more.

The National Film Theatre

The movement needed a forum to showcase their work, and it found a home At the National Film Theatre, which also showcased foreign filmmakers by upstarts Roman Polanski and Francois Truffaut.

The first “Free Cinema” program at the National Theatre consisted of three films: Lindsey Anderson’s O Dreamland; Karel Weisz and Tony Richardson’s Momma Don’t Allow; and Lorenza Mazzetti’s Together.

The final three programs at the National Film Theatre were largely devoted to foreign film; the fourth program showcased the work of Polish Directors; the fifth program showcased the work of emerging French directors, and The last of the programs at the National Film Theatre took place in March of 1959.

Free Cinema Filmography

O Dreamland by Lindsey Anderson

Momma Don’t Allow by Karel Weisz and Tony Richardson

Together by Lorenza Mazzetti

Nice Time by Alain Tanner and Claude Goretta

Free Cinema’s Major Players

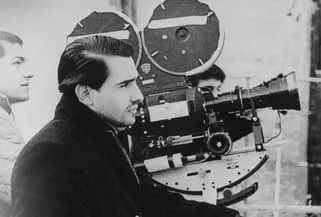

Karel Reisz

Karel Reisz, born in Chechoslovakia, emigrated to England in 1938 and joined the Royal Air Force; unfortunately his parents, of Jewish Descent, died At Auschwitz. After the war, he wrote for both Sight and Sound, and Sequence Magazine, which he co-founded with Gavin Lambert and Lindsay Anderson in 1947.

His first short film,Momma Don’t Allow, about a North London Jazz Club premiered at the National Film Theatre in 1956. His other documentary works included xi and We Are the Lambeth Boys, which were selected as entries into the Venice Film Festival.

Reisz made his feature film debut with the movie Saturday Night and Sunday Morning in 1960, which would put a little-known actor by the name of Albert Finney on the map. He would eventually make several major Hollywood films, including The Gambler (with James Caan), Who’ll Stop the Rain (with Nick Nolte and Tuesday Weld), The French Lieutenant’s Wife (with Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons), and Sweet Dreams (with Jessica Lange as the legendary Patsy Cline).

Lindsay Anderson

Lindsay Anderson was born in Bangalore South India. After his parents separated, his mother returned to England, where Lindsay would later on receive a scholarship to the University of Oxford. He served in the Army for three years, then returned to Oxford to complete his studies and graduated with an MA in English in 1948.

Anderson was a prolific Theatre Director at the Royal Court from 1957 to 1992, but also served as director for This Sporting Life (1963), Look Back in Anger (1980), The Whales of August (1987), as well as acted in the movies Chariots of Fire and Blame it on the Bellboy.

Free Cinema’s Impact

Free Cinema had a major impact on the British New Wave, and most of the documentarians would venture into narrative filmmaking, including Look Back in Anger (1958), The Loneliness of the Lone Distance Runner by Tony Richardson; and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1962), just to name a few.

Many of these films have been categorized as part of the kitchen sink realism genre, and many of them are adapted from novels or plays written by members of Britain’s “angry young men”.