1) Screenplay by Syd Field

The first book I ever read about screenwriting. Syd Field is the forefather of the how-to for screenwriting. He cracked the code of the three-act structure and paved the way for all other screenwriting gurus that would follow. As far as I know, he created the terms like “turning points,” and “pinch”, and much of the language that screenwriters use to describe elements and devices used in their scripts. (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

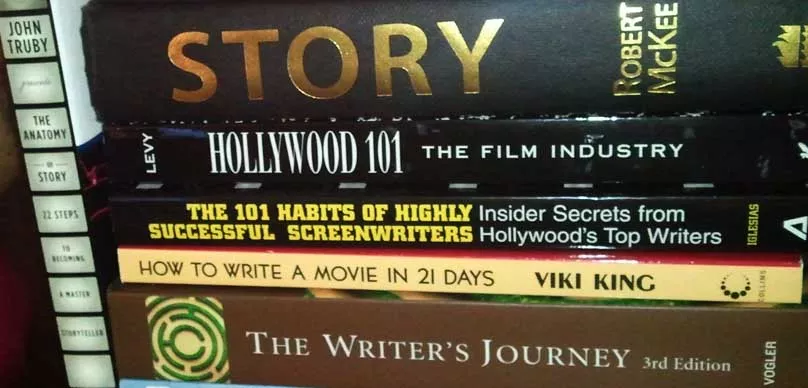

2) Story: by Robert McKee

Immortalized by the film Adaptation, McKee delves deeply into the components necessary for making a great script. I find his principles of “controlling idea” (which closely resembles Lagos Egri’s concept of “premise” in The Art of Dramatic Writing) and “gap between expectation and result” incredibly useful. I always turn to McKee’s teachings for guidance. (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

3) The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler

Vogler takes the workings of Joseph Campbell about myth and archetypes and breaks it down into easy to chew, bite-size portions. What makes Campbell so special? His writings about the universal appeal of mythological tales have inspired many other storytellers to create great pieces of work with timeless resonance — does George Lucas ring a bell? (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

4) Making a Good Script Great by Linda Seger

Seger’s book I found as a great companion piece to Syd Field’s Screenplay. What I particularly like from this book is her method of ramping up conflict by the use of “obstacles,” “compilations,” and “reversals.”

Also, check out Linda’s amazing podcast interview here: Making a Good Script Great with Linda Seger (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

5) Save the Cat by Blake Snyder

You can see echoes of all the other aforementioned writers in this book. What I like about Save The Cat is that it’s a stripped-down, fun read with a lot of helpful information. I especially appreciate Snyder’s Beat Sheet which shows with almost page number accuracy where to place those particular plot moments that help keep your story moving. Some might find it formulaic, but I think it functions very well and points to exactly the kind of scripts Hollywood has come to expect from writers. One of the best screenwriting books. (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

6) How Not to Write a Screenplay by Denny Martin Flynn

Just when you think you’ve got it all figured out on how to write a screenplay along comes this book to point out where you may have gotten it wrong. Despite the length of the title, it’s a quick read and VERY illuminating. As I skimmed through the examples of what not to do, I discovered what I was doing right, and most importantly what I was getting wrong. They say you learn from your mistakes, and reading this book sure helped to show how. (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

7) The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats by Cole Haag

This book was a required textbook back when I was at film school. Some of the formatting suggestions may be a little outdated, especially if you have Final Draft or Movie Magic screenwriting software, but there’s still a ton of knowledge to be gained about proper formatting. The quickest way to spot a novice writer is by how unprofessional their script is formatted — this book shines a light on the Hollywood standard. (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

8) The Screenwriter’s Bible by David Trottier

Not only do I dig this guy’s first name, but I found his book to be more current as far as the conventions of formatting. It covers a lot of ground with how to write a screenplay and everything else that goes with being a screenwriter and Filmtrepreneur, like how to register your script and how to write a query letter to literary agents. It’s a broad overview, but one of the most informative screenwriting books. (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

9) The Art of Dramatic Writing by Lajos Egri

This is actually a book for the aspiring playwright, but most if not all the principles can apply to screenwriting. Egri gives examples of poorly constructed scenes and explains why they don’t work — then compares and contrasts against scenes that do. This is one of my favorite books, and one I strongly recommend. One of the best screenwriting books out there. (FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE)

10) The 101 Habits Of Successful Screenwriters by Karl Iglesias

(FREE AUDIOBOOK VERSIONS HERE) Have you ever wondered how successful writers do it? If you’ve reached this point on my top ten, I would say, “of course you do!” There are good work regimens and not so constructive methods. This book gives us a glimpse into how the top Hollywood writers work, how they fight writer’s block, as well as deal with the daily grind of writing. I found it very insightful and definitely worthwhile.

BONUS: Pulp Fiction – The Screenplay by Quentin Tarantino

A must-read for any screenwriter. Tarantino…nuff said! These are our Top Ten Screenwriting Books You Need to Read. We hope they help you on your journey as a screenwriter. Remember just keep writing!

David R. Flores is a writer and artist (aka Sic Monkie) based in Los Angeles. He is the creator of the comic book series Dead Future King published by Alterna Comics and Golden Apple Books. Website: www.davidrflores.com & www.deadfutureking.com

Transcript for Robert McKee Interview:

Alex Ferrari 0:04

I'd like to welcome to the show, Robert McKee. How are you doing, Robert?

Robert McKee 0:08

Very well, very well. Thank you.

Alex Ferrari 0:10

Thank you so much for coming on the show. I am have been a fan of your work for quite some time. I've read your first two books, and I'm looking forward to reading your new one, which we'll talk about later character. But I was first introduced to your work in the film adaptation like so many. So many screenwriters and filmmakers were how, by the way, how, how was that whole process? I mean, it was a very odd request, I'm sure that you got when you got that call?

Robert McKee 0:40

Well, it certainly was, my phone rang one day and producer named Ed Saxon calling from New York and, and he said I am mightily embarrassed. This is a phone call I've dreaded. We've got this crazy screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and, and he has made you a character in his screenplay, and he has freely cribbed from your book and from your lectures, and he has no permission to do either. And, but we don't know what to do. So I said, well, send me a script, you know, I'll you know, see what's going on. So they sent me a script, and I read it. And I saw immediately that he really needed my character as a central to the film, because he wants me to, he wanted my character to represent the the imperatives of Hollywood. And that you have to do certain things certain ways, blah, blah, blah. And, you know, which is on one level nonsense. Such rules, they their principles, and there's genre convention, but anyway, but so I was a typical kind of need to slander Hollywood in favor of the artist. And, and they wanted me to do the slandering. So, but I realized that without my character there to provide some source of conflict. The story didn't work at all. So I said, and so I tell you what, I made two phone calls. I called William Goldman. And I said, Good, he was, you know, a student of mine. And I said, Bill, they there's a film and they want to use me as a character in it. What do you think? And he said, Don't do it. Don't do it. He said, it's Hollywood. And he said, they're out to get you don't do it. I said, Yeah, but I'm okay. But suppose I had casting rights. And he says, Okay, okay, who do you want? I said, Well, let's say Gene Hackman, is it? Okay. Okay. It'll be Gene Hackman, with a big pink bow around his neck. If they want to get you, Bob, they're gonna get you don't do it. So then I called my son. And I said, Paul, you know, and he said, do it. I said, Why isn't because Dad, it's a Hollywood film, you're gonna be a character in the Hollywood film. And he said, it'll be great. Do it. So I talked to Ed Sachs, and I said, Kenny, three things. One, I need a redeeming scene. I said, you know, you want to slander me fine. But then you can't leave it at that. You got he got to give me a redeeming scene. Right? To I have to have the controller the casting, I won't tell you exactly who to cast. But you got to give me a list because I ended need to know their philosophy. I mean, for all I knew this was the Danny DeVito Dan Ackroyd School of casting,

Alex Ferrari 4:28

you know, fair enough.

Robert McKee 4:31

I said, and very importantly, the third act sucks. And I cannot be a character in a bad movie. So we need meetings, they're going to have to be willing to rewrite. And, and those are my three conditions. And, and they agreed to them. And, and so they sent me a casting they gave me my redeeming scene and then they they they sent a list. Have the 10 best middle aged British actors alive? You know, everybody from Christopher Plummer to Alan Bates and I, and and I looked at the list. And I said, I want Brian Cox. And they said, Who's Brian Cox? And I said, He's the best British actor you don't know. Because Brian had been a student of mine up in Glasgow, and I'd seen him on stage in the West End of London and, and what I didn't want, see all those actors. They're all wonderful. But there's always actors have this Love me Love me thing, no matter what they want to be loved. And there's always this subtext like my heart's in the right place. And I really, you know, and I don't want to be loved. I really don't want to be respected, I want to be understood. And I want to inspire people and educate, but I do not want a bunch of people following me around like a guru. Right, loving me, right? And I knew that Brian would not do that. And, and then we had meetings and about the Act Three, and eventually got to a never got to a perfect accuracy. But it got to a point where I could sign off on so and it was, so they took my son to a screening at so at Sony and I said, you know, we think ball, and he said, Dad, he said, Brian Cox nailed you. Which I thought was great. So you know, and it was, it was, but that's not the, you know, I was I put myself in a funny date. So it's not just, but yeah, it was, um, it was a difficult choice. But I think William Goldman was wrong, that, you know, there was a way to you have your cake and eat it too. And I think an adaptation is loved. Oh, and millions and millions of people. So, so it certainly didn't hurt my brand.

Alex Ferrari 7:20

It didn't hurt your brand or business, I'd imagine. It's the term irony comes to play where you would be working with Charlie Kaufman, on a script, where your character is the establishment that he's trying to get away from and to give art but yet you are working with him to put the script together and finish the third act, which is amazing. Charlie,

Robert McKee 7:42

Charlie's one of those guys. He's got, you know, a great talent. But he's a bit delusional. What he wants to achieve is the commercial art movie. He wants it both ways. He wants to be known for making art movies, but they have to make money too. And a lot of it because he knows that, you know, his career. If he loses money, it's over. And so and, and so he wants to he wants to create the commercial art movie and a salsa dance understood, you know, things, the notion of the commercial art movie, you know, the, the, the English Patient and films like that. And I you know, in the meetings with a spike and and, and, Charlie, I, you know, I pointed out to Charlie, so you can't have it both ways. It's a you, you know, you if it's a true art movies have a very limited audience period. And art filmmakers understand this. And they budget accordingly. You want 30 million

Alex Ferrari 8:59

for an art film?

Robert McKee 9:03

Was 5 million we could, but Okay, so anyway, but it was. Yeah, the irony of it is wonderful.

Alex Ferrari 9:10

So, so you've worked with so many screenwriters and filmmakers over the course of your career, what is the biggest mistakes you see screenwriters, new screenwriters to the craft make?

Robert McKee 9:24

Well, it's not mistake so much. Yeah, I guess it is a mistake. But, uh, there's two problems. One is cliches. And they think that it that they want to be, you know, like an artist, they want to be original, but at the same time, they want. They want to be sure that it works. And so they recycle the things that everybody's always done. And they've tried to recycle them with it. difference and which is absolutely necessary, I mean, that's I get it, you're not going to reinvent the wheel, you have to just spin it yet another way. And, but then they get very easy once they sell their soul. It's hard to get it back. And, you know, you can pour on your soul for a while, but you've got to get the cash to get back. And, and so that's the war on cliches is not some, you know, it's not a fault, it's just a problem everybody faces. And, but there's a greater problem. And it's the willingness to lie. In an effort to tell their story to get it out, somehow they get it together. And they will write characters and scenes, and whatever that that lack credibility that they know perfectly well, in their heart of hearts is pure corn of some kind. And it's a it's, they're bending the truth. It's not it's, there's something false to some. And, and, and to, to, to get to something that is really profoundly honest. And it doesn't matter what the genre is, from action, to comedy. to, to a you know, as an education plan, something very interior doesn't matter what the genre is, there's truth, and then there's lie. And somehow they think that because it's fiction, that gives them a license to lie. But but they don't have that license, they have a an obligation to express the truth of what it is to be a human being and in whatever genre, they're they're writing, they have a, they have a an obligation, if they're writing comedy, to really stick a knife in some sacred cow and expose the bullshit of society. I mean, they, you know, it's not enough to be amusing. comedy is a is an angry art, that savages, all those things that, that that that are false in life, and starting with politics. Right. And, and so there's they, there's a willingness to, to fit and lie and in order to please that, okay, let me take a step back. I bulldozing cliches and truthfulness are all the byproduct of the young writer, especially the young writers desire to please they want to be loved, they want people to love what they do they want to please people. And so they write what they think, is pleasing for people, whether it's all the cards in fast and furious. Right, or the sentimentality or whatever they want to please people and and which is fine, but you can't please everybody and so you're going to write for a certain mind a certain audience a certain mentality and an educational level and taste and whatnot in a certain group of people that you know, are out there, they're like you pay and and you can't please everybody. And and so, a film like for example, Nomad land is certainly not trying to please there's an audience for it, that will get it and enjoy it and and recognize this as a deep truth about our society and about human nature.

But it's, it's not going to have a mass audience. And because it will turn off more people than it will turn out. And, but it's, it's a excellent film is an honest film. So that's the I think it's fishing around here. Because when you open the door and say, you know whether

Alex Ferrari 14:53

you're wrong, there's 1000s of things

Robert McKee 14:57

to bring up, but if I can do it down, it's that it's that the willingness to please results in recycling cliches, and basically not telling the the, the, the dark truth of things. And so you have to be it's tough, you have to be disciplined not to copy other people's success, but to, to write what you honestly believe to be the

errors in the central new genre.

And, and be rigorous about that.

Alex Ferrari 15:36

Now, one of the the hallmarks of a good story is conflict. How do you create conflict in a story?

Robert McKee 15:46

Well, depends on where you start. If you start with a choice of genre, let's say you're going to write a thriller. Right? You know, the source of conflict immediately by that choice. I need some kind of psychopathic villain. Right? I need Russell Crowe, in unhinged. Why? And so that's done for you. So that the genre sort of automatically tells you, right, on the other hand, if you're telling a family story, and that will be called domestic. Until the characters are a family and it's a family with problems, wow. The conflict could come from any direction. Who's with? Is it the mother? Is it the father? Is that rebellious children? Is it Whose is it? Some some, you know, older grandfather grandmother figure that's pulling people strings, and you know, whatever, given a family what's wrong with this family? And so you have to figure out what is it and is it social, or psychological? Is it instinctive is a deliberate you have to think your way through all that. And so you, you you start with a family and you create a little you know, a cast? And then and then you ask the question or what's wrong with this family. And a million different things can be wrong in human nature inside of a family. And that requires knowledge, you have to understand people, you have to understand that you know, the mother, daughter, mother, son, Father, daughter, Father, Son relationships, and, and you need to dig into your own experience. And ask yourself, you know, what was wrong in my family? What What do I believe, to be the truth about families? And, and, and that the genre doesn't give you that answer. And so, you have the answer will come from your depth of understanding of human nature, human relationships of a certain personal kind in this case. And, or if you're writing comedy, so as mentioned, the starting place of writing a comedy is to ask yourself what is pissing me off? What in this world is pissing me off? Is that relationships? Is it men women? Always it? Is that the is that the the the the social networks? Is it is it politics? Is it the military? Is it the church? Why what what is what what do I hate? What's pissing me off? Because the root of comedy is is anger. The comic mind is an angry idealist comic comics are idealists who want the world to be perfect or at least and when they look around the world they see where sorry, sick one place it is. And, and they realize that they're complicit, they're part of it too. And so what spacing me off then it points them in a direction to an institution or behavior in society. me like I think that great comedy series. Curb Your Enthusiasm. You know, and, and, and yes, you know, what is pissing me off and he will finds really egregious fault in, in, in people's lack of propriety. Or, or logic or clarity of thought, you know, why should there be a handicapped stall in toilets? Right that no one can use except the two times a year that a handicapped person comes into this particular toilet. Okay. Right. That is

Larry David, that is an egregious absurdity and it infuriates him. And so he goes into the handicap stall, and sure shit, this is the day

a guy in a wheelchair. So, um, so that, you know, that that's, those are the various things, you know, you, you look at yourself, as a writer, and you you have to understand your vision of life, you have to understand the genres. When you make a choice, there's certain conventions. And, and a, you can bend those conventions, what breaker if you want, but not without an awareness of what the audience expects. And so somehow, it'll between picking the setting and the cast, the genre, and then looking inside of yourself, like your comic wouldn't ask you what's pissing me off? You find your way. If I if you're in conflict, and the the most importantly, you know, it has it that you know that that conflict has to be something you deeply believe in. Now, or, or you will do what we were talking about earlier, you will fall prey to cliches because you'll you'll create false conflict, false antagonist empty, a cliched antagonisms. And like that. So it's a very important question. Now.

Alex Ferrari 22:28

So as far as one thing a lot of a lot of screenwriters try to get away from is structure, saying that structure and trying to fall into side of a structure is, it's like holding me back as an artist and I need to be free and I need to run free like a wild stallion, I personally find structure to be very freeing, because it gives me a place to go. How do you approach structure?

Robert McKee 22:55

Well, in this day, people have a course accused me of imposing structural rules in my teaching, and it's nonsense. When

I am opposed to structure, it's inhibiting my creativity do not know what the hell they're talking. They just don't they use the word structure. But they wouldn't understand or know story structure, if it fell from a height under their foot, okay, they just don't know what they're talking about. structure in every scene, ideally, is a turning point of some magnitude, the character's life, they go into a situation wanting something. And something in that moment, kind of prevents them from getting it. They struggle with that. And they either get what they want, or they don't get what they want. Or they get it at a price or they don't get it but learn something. Change takes place. And it's in a simple scene is minor. And then these changes per scene build sequences in which moderate deeper change wider change happens, these sequences build x in it. And then that climax is a major turning point that has greater depth or greater breadth or both have impact on a character's life. And so minor moderate major changes are building a story progressively to an absolute irreversible change at climax. Now, why would anyone object to what I just said? Why would anyone think that you can change Do concrete scenes in which nothing changes. And do that three scenes in a row and people will not be walking up. They come there, they come to the writer, they read a novel, kind of trying to have insight into life as to what forces in life positive and negative, bring about change outwardly or inwardly in characters lives. I mean, that's why we go to the storyteller. And so and so why would you not want change? Or why would you want repetitious change? Because the same change degree of change, that happens three times in a row, you know, we're bored. So because it's not giving us what we want, it's not giving us the insight that into character that we want. And so people who say they're opposed to structure don't understand what structure is it they don't understand, it's a dynamic and a progression of minor moderate major changes. And so I have no patience with that kind of ignorance. Hear the people who say that are the very naive, ignorant, really, people who think that if they just open up their imagination, emotion, picture will flow out of it.

Alex Ferrari 26:30

Very true.

Robert McKee 26:32

And, and they are childish in that way. I mean, you open up your imagination and see what flows out, then you have to go to work on it. And you have to step back from every, every time you you know, or let me put you this way. What in truth is it to write? What is writing actually, like, as an experience, you open up your imagination, and you have an idea for a character or two or three, and you write a page, things happen? Action reaction dialog, that when you write a page, that takes 20 minutes, then what do you do? You read that page? And you could take it does this work? would he say that? Would she act like that? would this happen with it? Is there a better way to do this? And is this repetitious? Is there a hole does it make sense, you constantly critique what you've written, and you go back, and you rewrite it. And then you read it, again, you critique it again. And this goes on all day long. And so you go inside to create, you go outside to critique, you create, your critique you curate, and the quality of your critique that guides your rewriting is absolutely dependent on your understanding to make judgments, when you ask the question, does this work? You have to know what works and what doesn't work. And, and so that on one level, everything you do is structure. Its structured to have a character say x and another character respond with y that structure action reaction, that the person who said x did not expect to hear why

Alex Ferrari 28:36

right exit Exactly.

Robert McKee 28:39

And that structure that beat of act reaction and human behavior, that structure. So is I said, People say this, say it out of out of emit amateur understanding of what the creativity, what the act of writing really is.

Alex Ferrari 29:07

And I, whenever I've come up against that, when I say no, every you know, every movie has some sort of structure. Most movies, especially popular movies have structure. And your definition of structure is wonderful. They always throw out Pulp Fiction, and I'm like, no Pulp Fiction is an extremely structured film. Do you agree?

Robert McKee 29:28

Yeah. I've when I was we were talking about when I was when they were doing adaptation, and I was working with Charlie Kaufman. Charlie had exactly that attitude. I said, the third act doesn't work. We have to restructure it. And in the end is his face went into a panic mode. He didn't want you know, scared the hell out. He said, I know. I know that. It needs some, you know, just it'll come to me it was a clo and whatnot. And it's as easy as I don't write with structure. He said that I don't write with structure. I said, Charlie, would you like me to lay out the three act design of being john malkovich as because it's a three act, play, want to hear them, act 123. And, and he almost ran out of the room. He didn't want to hear it. He wants to live in the delusion that it somehow flows, and there is no structure. And when in fact, subconsciously, at least being john malkovich is a three activist

Alex Ferrari 30:48

is a great, it's

Robert McKee 30:50

a model, it's a model, BJ Mack is a model three act design. But it's but to the romantic like, Charlie, he doesn't want to hear it. Because he thinks that that's going to constipate his creativity. And I have to agree with it. If he wants to write out of this notion that it's all a flow. And if he is aware that there's a, that there's a design happening, it would, it would inhibit him. So it's because he's a good writer, he's very talented. So it would be better for him to live in that delusion, and let it all pour out. And then he goes back, and his taste guides the rewriting and so forth. And, and, and so if you're talented, like Charlie and, and the idea of structure is frightening, then you should listen to those feelings. And not think about structure and just, you know, do what you do, and hope it works.

But

that's rare.

Alex Ferrari 32:10

Very, very, very rare. But yeah, but and so for everyone listening, you have to understand that someone like Jeff Hoffman is writing. And as he's writing, he's subconsciously working within the three act structure, honestly, on a subconscious level. And even the great writers is like, Oh, I never even think about outlining or plotting, is because they have such a grasp of the craft, that it's already pre wired in them. It's like me building a house, I wouldn't even think twice about how to pour a foundation, or how to how to how to lay out the walls, because I've done it a million times. I don't have to sit there and think about it, it's just done. But that is rare, and it takes sometimes years to get to that place or you're a prodigy, which happens once in a generation or twice in a generation.

Robert McKee 32:57

And and you're absolutely right. That's very, very well put and, and in fact, it goes beyond that you have been watching the stories on screen you have been reading them in novels, you've been to the theater, that form form is a better word than structure that form of action, contradictory reaction and reaction to that and a giant dynamic of action reaction building to change that is so built into you as a as a reader as an audience member from I don't know two three years old. Mother read your little you know, bunny rabbit stories, right? Your bunny rabbit goes out and something happens that not happy for the bunny rabbit and then you know of bunny rabbits mother comes along and pictures things whatever it takes, I mean that that form is ingrained in you from from the earliest. And so you do know it?

Alex Ferrari 34:08

Without question. Now you do more dialogue is something that is you've wrote an entire book dedicated to dialogue. Obviously, your first book is story. But your second book is dialogue. What are the three functions of dialogue in your opinion?

Robert McKee 34:25

Well, there's many of them and certainly one of them is is the obvious one of exposition by various means. So for examples simple in writing dialogue, a character has a certain vocabulary so for example, you you've done construction on houses, right? Some sure I And so how many different kinds of nails Do you know? From spiked to tact of,

let's say 10? Yeah. Okay. Now most people may know, to me one nail on a screw, basically, that's all they know.

Okay. So if if in there, if a character in their dialogue uses the, the carpenters terminology. And even metaphorically, you know, call something a five, many nail, right? The fact that he knows the difference between a temporary nail and pipe and whatever it is, his exposition is it tells us something about the life of this character, by the very word, the names of things that that this character uses in their vocabulary helps us understand the whole life of this character. So if somebody grew up, you know, around boats, and they use nautical terminology, right? And so that they the language inside of the dialogue, all that just the vocabulary alone gives us exposition, it tells us who is this character? What's their life been like? Etc. Okay, then, at the same time, the characters talking about things that are happening, or have happened. And when somebody says, you know, you're not going to leave me again, we are to instantly know, that's it, she's already left them once, at least before

Alex Ferrari 36:46

it says it says volumes with one word.

Robert McKee 36:49

Yeah, there's no word again. But so we have an insight into what their life has been like, in this relationship. And so that's number one is is, is exposition. And number two is action. When people speak, what they say, is an action they take in order to get what they need and want in the moment, but underneath that is what they're really doing. And it's what in the subtext, the action they take in the subtext is what's driving the scene? So when somebody says, Well, I didn't expect that. Right? What they're really doing, perhaps, depending, right, is attacking, criticizing the other person for doing something that's completely inappropriate. What they say is, well, I didn't expect you to say that I didn't expect you to do that. I didn't expect that. But what that is, is a way of attacking another person for inappropriate behavior. And so it's right. And so and so the dialogue is the text by which people carry out actions. But underneath the dialog, is the true action. And it that's based on a common sense, understanding that people do not say out loud and do out what they're really thinking and feeling. They cannot, no matter how they try, if they're when they're, when they're pouring their heart out and confessing to the worst things they've ever done. There's still another layer, where they're actually begging for forgiveness, let's say, right? So by confessing, actually, you're begging for forgiveness or whatever it is. And so dialogue is the outer vehicle for interaction. And, and the great mistaken dialogue is writing the the interaction into the dialogue. stead of having somebody confess, did they beg Please forgive me, please forgive me, forgive me, forgive me. Right. And, and if somebody is actually begging, there's got to be another level of what they're really doing underneath the baking. And, and so you have to, you know, the writer has to think to that by begging. What that dialogue is actually a mask for manipulating that person. Do what you have to do, right. And so, exposition, action. Okay. And then, you know, just beauty. Just Just wonderful dialogue, in character, and all that, but but a way of creating a surface that is that it draws us. Because, you know, we just love to see scenes where characters speak really well. in there. And even though even if we're using just gangster talk, good gangs, your dog, it's right to talk to each other and that kind of rap and that kind of unite. Right? That's, that's a form of beauty. It's wonderful, you know, it's pleasurable, right. The dialogue ultimately ought to be pleasing, and in his sense of kind of verbal spectacle. And so that's just, you know, that just three off the top of my head functions, but there's is there's much more right and I, I like I'm sure like you, we all love. Wonderful, memorable quotable dialogue.

Alex Ferrari 41:24

Yeah, very much like it's so obviously Tarantino and Sorkin and Shane Black and these kind of screenwriters, their dialogue is just, it's poetic in the way that they write something, certainly is, certainly, and the genius of them is they're able to do the first two things you said, within that poetry, as opposed to just poetry for poetry sake,

Robert McKee 41:46

which is, you know, that is that just decorative. They all happens all at once. You know, you're getting exposition, see who these characters are, whatever actions or reactions are driving the scene, and it's a pleasure to listen to.

Alex Ferrari 42:03

Now, one thing I've noticed in years and even in my own writing descriptions, in a screenplay, a lot of screenwriters, when they starting out, they feel like it's a novel. So, they will write a very detailed description about a scene or about something, where from my understanding, over the years, less is more and it becomes more of a of an exercise in Haiku is than it is in the novel writing. Can you kind of talk a little bit about the importance of of compacting your description?

Robert McKee 42:37

Well, it does need to be economical. Of course. On the other hand, it has to be vivid,

Alex Ferrari 42:44

right?

Robert McKee 42:46

And that's, you know, where does that balance strike you that the ambition is to project a film into the readers head. So that when they read their screenplay, they see a motion picture without camera directions without you know smash CUT TO for transitions and, you know, Dolly on and you know, and you know, pull focus, whatever nonsense, you got to use the language and description to create the effect of a motion picture, then you only use ideally, you only use the master shots, it you you only the the the shots, the angles, the setups, camera setups that are absolutely necessary. And no more you do not try to direct the film. And, and instead, you project a motion picture into the readers head. And, and, and so you need to it over, often in overriding and when, in fact, was not only overwritten, but it's not vivid. It's because writers rely on adjectives and adverbs. And what they need is to know the names of things. You know, he, he, he picks up what we're talking about before a big nail. Well, you know, big is an adjective. And so, put an image in the readers head, he picks up a spike. Spike is a vivid image. A he, he walks slowly across the room, will slowly is an adverb. Right? Right. And so you name the action of verb is the name of an action. He pads across the room he ambles, he strolls he saunters. He you know, Waltz's is an active verb without an adjective, adverb, concrete nouns without adjectives. And we see things and we see actions. And it becomes vivid. It reduces the word count. And, and here's here's something a good it's a good note for writers take your screenplay. And, and search the verb is or our urge is an are throughout your descriptions and eliminate every single one of them. know things are nothing is in a screenplay. Everything in a film is alive. And action. So you know, a name the thing. So a line like a big house, there, there is a big house on a hill.

Okay.

And what's a big house a mansion or a state? a villa? What's a, you know, a hill, a mountain. At add and add and turn it into a villa sits just that verb sits is more active than is a big house sits with a spectacular with this spectacular view. And so easy, a big house up high with a great view. And it's an image and it's active, it sits sprawls across, whatever. And so active verbs concrete nouns, and and make us see a movie. And every writer finds every good writer finds their own personal way to do that. And Paddy Chayefsky wrote elaborate descriptions. Harold Pentre described, nothing, nothing. He would just go interior kitchen dialogue, dialogue, dialogue, dialogue, describe nothing. And because his attitude was, we all know what a kitchen looks like. And they'll probably play it in the garage anyway. But if they mess if they mess with my beats of action reaction and you know, in dialogue, then they're in trouble. Okay, so every writer has to find their own way to accomplish the task of a vividly projecting emotion picture in the imagination, as you turn pages who make them see a movie.

Alex Ferrari 48:23

Now, your new book is called character. And I wanted to ask you a couple questions in regards to character because, arguably, I always like to ask the question, do you start with plot or you start with character I always say to people, you don't like Indiana Jones, his plots aren't nearly as memorable as Indiana Jones James Bond's plots aren't as memorable as James Bond. Like I don't you throw me the plot of thunder ball. I don't remember. I remember scenes, but I do remember James Bond. And that's what draws me back to his stories. So, can you talk a little bit about the difference between roles and character?

Robert McKee 48:58

Well, a role is a generic term. And so hero is a role villain is a role victim is a role. You know, sidekick is a roll. goon is a roll. shopkeeper his role in the role is as a position in a in a cast. as defined by its relationship to other characters, and or a profession. Like waiter, asked driver. And, and they're generic, they wrote something waiting to be filled by a character. And as a character comes into a story to fulfill a certain role but it's a it's a You know, it's it's a, it's a generic to that to that genre. And so if you have a family, the roles are mother, father, children guide, they're okay, those are roles, characters are our unique human beings, we inhabit those roles. And and there's a design of a cast, such that the protagonist, and the central character at role is the most complex character role. And they are they, they're, depending on the genre, they are the most dimensional character of all. And they are ideally, they, they are the center of good, there's a, there's a positive human quality, not every way certainly, but there's, there's some quality, within the complexity of that character, with which we recognize we empathize, we recognize a shared humanity, the character is then in orbit around that character that protagonists are less dimensional, but they can be dimensional as as well, then you go all the way out to the second third circles, where you have people only playing a role. cashier, restaurant cashier, okay. Now, even when you're writing a scene where your character goes up to the cashier in a restaurant, to pay a bill, and discovers that his credit card is cancelled, right, you have a clerk standing there, at the at the take, who takes the credit card and finds that it's, it's been rejected that clerk character, he be very useful to imagine that role, very specifically, what kind of human being, you know, is she or he, it because it does the, the way in which that clerk that roll says responds to your card is canceled. Your card didn't go through the, the, the way you write the words and gesture for that character gives her a trait. And so roles have traits and, and to make, even that moment, when there's a human being behind that, that trait. And so if she's sarcastic, if she's fed up with with the job itself or with with people whose cards never work, or she's sympathetic because her cards don't work.

Alex Ferrari 53:19

So,

Robert McKee 53:21

so, even in a in a simple role like that, you try to write it with a as a specific trait in the way in which he deals with that moment. And it creates a character for an actor. And so the actor come in there and realize, Oh, this is an antagonistic clerk or this is a sympathetic cleric, or an indifferent or bored or falling asleep, or glancing at her watch constantly, she just wants to get out of here, whatever it is, you give her a trait. And that makes her a character, she sends the GM to life and it gives the actor something to hang their performance on. And so dimensions the protagonists, the most dimensional of all dimensions are contradictions within the nature of the girl. And so you populate that with in my book on character, I look at characters everybody from from Odysseus in Homer's Odyssey has an eight dimensional character, all the way up to Tony Soprano, as a 12 dimensional character Walter White, as a 16 dimensional character. And so and so the complexity of character today given long form television, especially, is at is becoming your astronomical And then you have to give all the, that every one of these dimensions if a character is, is kind and cruel, okay? Sometimes they're crying, sometimes they're cruel. Therefore, you're going to need a cast of characters where the protagonist, when they meet character a, they treat them kindly character B, they treat with, with a slap with cruelty and, and so you need to design a cast around each other characters. So that when, whenever any two characters meet, they bring out sides of their dimensionality or traits of behavior that no one else brings out of them. And so, every single character is designed that whenever they encounter any other character, they bring out each other's qualities in ways that no other character does. And, and when you have a, you know, when you have that kind of cast, where every single character services, every other character, and no redundancies every relationship is unique. every relationship develops a different aspect or a different dimension. Then you have a fascinating group of people that creates a world that the audience can really

Alex Ferrari 56:38

dive into,

Robert McKee 56:39

dive into now, you know, when characters when and carrot one characters behave toward each other in the same way, no matter who it is. That, you know, that's it's a boring and do it's false. People do not treat other people, different people the same. Everybody behaves in a uniquely subtly but uniquely different way, depending upon the relationship. And it takes a lot of concentration and imagination in the writer to realize that every relationship brings out different sides of the character's nature.

Alex Ferrari 57:21

Now, I'm gonna ask you a few questions. Ask all my guests. Robert, what are three screenplays every screenwriter should read? You see? I don't answer that question. Okay. For this reason, I don't want people to copy anybody. Okay, fair enough.

Robert McKee 57:46

And so if I say, you know, if I named my, you know, my favorites, like, say, trying to tell people you know, then run to study Chinatown and emulate it. And that's a mistake. The really important question to ask people is, what's your favorite genre? Because they should be writing the kind of films they love.

Alex Ferrari 58:15

It's a good point, what

Robert McKee 58:16

I love, what are my favorites may have nothing to do with their favorites. And so the first question is, you know, what do you love? What kind of movies do you go to see what kind of things do you read? What do you love? And then seek out those? And the second thing is that if I name favorites, and, and that they, you know, they're in their pieces of perfection. Okay. What does that teach the writer? They got a model of perfection. Great. Okay, that's important, you should understand you should have an ideal, what you're trying to achieve. But one of the ways to achieve it, is to study bad movies. break them down and ask yourself, why is this film so boring? Why can't I believe a word of it? Why does this fail? and break it down and study it? To answer what this What does it lack what went wrong, etc. Okay, and then rewrite it.

Alex Ferrari 59:37

Just thing,

Robert McKee 59:39

rewrite it. fix that broken film. Because that's what you're going to do as a writer. Your first draft is going to suck. And you're going to go in and try to fix your broken script. Try to bring it to life. Try to cut edited shape and rewrite it reinvented, you're going to read it over and over again, right? Having fixed broken films, not just one, but many, many, many take bad movies, studying them and make them make them work is practice for what you're going to have to do with your own screenplay. Because it's not going to work in the beginning, it's going to need a lot of work to work. And so having rewritten bad films to make them work is, is a real learning experience. And so I say, study good films are of your genre, so that you have a an ideal that you achieve, rewrite the bad ones to teach yourself how to fix broken work. And so, and that's a personal choice. I can't say what that should be for those people. For every one of them, loves whatever they love, which may or may not be what I love.

Alex Ferrari 1:01:00

Now, where can people find out more about you? And where can they purchase your new book character? Amazon? It's pretty much it is pretty much it nowadays, isn't it? It's pretty much it nowadays, isn't it? Amazon.

Robert McKee 1:01:17

bookstores, I'm sure are opening up. And if you know if you love bookstores, as I do, you know, you can go to a bookstore and get it. But the most direct way that will be there in your budget for the next morning. It's incredible what they do, what Amazon does, and bash, you know that the other other Barnes and Noble stew or whatever it is, but yeah, it's very simple. You just go to amazon.com. Right? Just write the word McKee. And comes story, dialogue, character, in hardcover, in an audio and in Kindle,

Alex Ferrari 1:02:05

and everything else? And then how can people read it? And how can people learn more about you what you offer?

Robert McKee 1:02:13

Ah, the go to make peace story.com. The key story.com will take you to our website. And we have a upcoming. We've been doing webinars now for a year and a half since the plague hit us. And they've been very successful, very, very pleased with it. And in July, we're doing a series on action. Nice on the action genre. And so these, these are every Tuesday, three Tuesday's in a row. And they're two hour events, hour and a half worth of lecture and a half hour of q&a. Then on Thursday, I I give an additional two hours of q&a.

Alex Ferrari 1:03:01

Fantastic.

Robert McKee 1:03:03

And because I realized how important it is for people to get answers to things they're working on. So So Tuesdays and Thursdays for three weeks in a row. And there's you know, four hours of material each week. So and we will we will look at the action genre in depth with lots of illustrations and examples of an adage and I love giving these acts. webinars. And it's a favorite of mine. Actually,

Alex Ferrari 1:03:38

I love a good action movie is it's hard to come by nowadays. So I appreciate it. Robert, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to to my audience and I appreciate all the work that you have done over the years and help so many screenwriters as well. So thank you so much for everything you do.

Robert McKee 1:03:54

It was a lovely chat. Great chat. Nice talking to you.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.