EARLY WORKS (1962)

Few figures in the world of cinema cast a shadow as long as Francis Ford Coppola’s. He’s a giant of the art form, with a handful of movies that have redefined film as we know it. His inherent genius, which has cost him considerable grief throughout his career, is abundant enough to be passed down to his offspring.

Indeed, the Coppola family dynasty is something of a phenomenon– there’s his daughter, indie darling Sofia Coppola, as well as his filmmaker son Roman (and that’s not even counting more distant family like Jason Schwartzman or Nicolas Cage). His recent films may only have a fraction of the power of his early work, but Coppola’s place in the annals of cinema history is undeniable.

Born in Detroit, but raised in New York City, Coppola found his love for film by way of the theatre. Suffering from polio during his childhood, Coppola entertained himself by putting on puppet shows and dabbling with the family’s 8mm film camera. This led to substantial training in music and theater, capped by a bachelor’s degree from Hofstra University.

It wasn’t until he enrolled in graduate school at UCLA that he began formally studying film. Influenced by the works of Elia Kazan and Sergei Eisenstein, Coppola was a member of the earliest wave of directors to directly benefit from a dedicated filmmaking program. It was during this time that Coppola cut his teeth with shorts like THE TWO CHRISTOPHERS and AYAMONN THE TERRIBLE.

What’s interesting about the beginnings of Coppola’s career is that his work found wide distribution before he even graduated. A full five years before he earned his graduate degree from UCLA, Coppola had already made several feature-length films. Some of these have been lost to time, such as his first work– 1962’s TONIGHT FOR SURE– a softcore comedy meant to titillate rather than entertain.

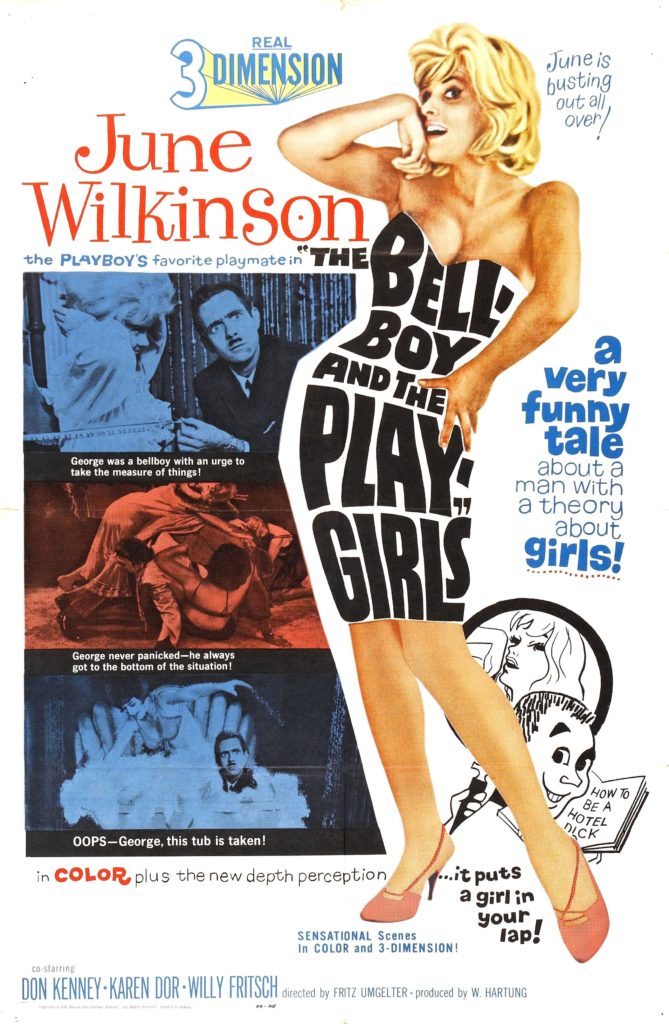

THE BELLBOY AND THE PLAYGIRLS (1962)

His next work, however, exists in bits and pieces around the internet. Also shot in 1962, THE BELLBOY AND THE PLAYGIRLS was more of an editing job than a directing one. However, recutting and adding new footage to German director Fritz Umgelter’s film MIT EVA FING DIE SUNDE AN earned him a full director’s credit.

The film, shot in black and white, was yet another stag/nudie comedy. The only clip I’ve been able to find, presented above, makes no mention of whether the footage belongs to Coppola or Umgelter. It doesn’t appear to be dubbed, so for the sake of this article I’ll assume it’s Coppola’s.

This brief snippet shows an intimate scene between newlyweds, as the husband tries to cajole his timid new wife into sex. Coppola shoots wide and straight-on, capturing the action dispassionately until we pull back to reveal that these characters are actually actors rehearsing for a play.

It’s a playful move on Coppola’s part to deceive us using only the boundaries of the frame– an effective trick that hints at Coppola’s budding desires to challenge convention and redefine the language of cinema.

BATTLE BEYOND THE SUN (1962)

That same year, Coppola found work as an assistant to legendary B-movie producer Roger Corman. Coppola’s first task under Corman was a daunting one: westernize an existing Soviet sci-fi film entitled NEBO ZOVYOT for American audiences.

Coppola’s take on the material, subsequently retitled BATTLE BEYOND THE SUN, became a schlocky monster film, albeit one with the conviction and resourcefulness of a young director with something to prove.

BATTLE BEYOND THE SUN (presented above in its entirety) concerns a space race between a unified Earth’s two latitudinal hemispheres, set in a then-future 1997. Which is hilarious, by the way. When the South Hemis nation attempts to beat the North to Mars and crash-lands on a nearby moon, the two powers must work together and fend off vicious space monsters so they can return to Earth safely.

This film is probably the epitome of Eisenhower-era B-movie cheese. Spacecraft models and props are janky, special effects are laughable, and the limited understanding of actual space travel is preciously quaint. However, it is surprisingly watchable, if only for the glimpses of Coppola’s earliest directorial choices.

His largest contribution to the film, besides the dubbing over of dialogue with American actors, was to inject a space monster battle midway through the film. Long before Ridley Scott made the sexualization of aliens cool in ALIEN (1979), Coppola crafted his dueling monsters to resemble vaginas and penises. This was a common characteristic of the lurid films that Corman produced, all of which were churned out rapidly and cheaply to maximize profit.

Ultimately, these films aren’t reliable indicators of Coppola’s growth as a filmmaker. Put simply, they’re glorified editing jobs where Coppola got to re-conceptualize an existing film and conform his edit accordingly. However, they’re fascinating looks into how film school students gained experience in the early days of the institution, when the costly nature of celluloid prompted experience gained via unconventional avenues.

Coppola’s work with Corman would eventually lead to the making and distribution of his first, true feature film. His early works served as important stepping-stones on that path, and now they serve as assurance for up-and-coming filmmakers that even the greats had to start somewhere.

DEMENTIA 13 (1963)

In 1963, director Francis Ford Coppola was deep into his apprenticeship with schlock mogul Roger Corman. That year also found Coppola in Ireland, working as the sound man for Corman’s feature THE YOUNG RACERS. When filming was finished, Corman found that he had a substantial amount of money leftover in the budget.

He may not have been a great film director, but Corman was undoubtedly a shrewd businessman, and he saw an opportunity to invest that money in Coppola’s untapped talent.

Corman gave the money to Coppola, with an assignment to stay behind in Ireland with a few of THE YOUNG RACERS’ cast members and make a low-budget horror film in the vein of Alfred Hitchcock’s PSYCHO (1960). Coppola responded to the challenge with DEMENTIA 13, his first true feature film of his own making.

While today the film comes off as understandably dated, low-budget and schlocky, it also offers a captivating insight into the mindset of a young, hungry director who would go on to become one of the greats.

The story of DEMENTIA 13 is well-rooted in classical and cliche horror-tropes. When her husband unexpectedly dies of a heart attack during a late-night boating excursion, Louise Haloran (Luan Anders) unceremoniously dumps his body overboard and heads to his family’s ancestral home in Ireland.

Acting under the guise that her husband is still alive and absent on a business trip, she maneuvers to get written into his mother’s will so she can cut out with a hefty portion of the family’s wealth. What she doesn’t count on, however, are the meddlings of her husband’s two brothers (William Campbell and Bart Patton), their macabre obsession with their deceased sister Kathleen, and a mysterious axe murderer stalking the grounds.

Despite DEMENTIA 13’s campy, trashy roots, the cast seems to be aware that they’re working with a great director, accordingly giving themselves over entirely to their performances. Anders is the archetypal Hitchcock blonde at the center of the story, and her shrewd, calculating ways aren’t as off-putting as they are lurid and compelling.

Campbell and Patton are the brothers to Louise’s dead husband, and they embody stubborn conviction and haunted torment, respectively. Veteran character actor Patrick Magee delivers a standout performance as Justin Caleb, the family doctor whose gruff mentality raises questions about his true intentions within the story.

DEMENTIA 13 is positioned as a slasher film, but it also dabbles in the murder mystery genre by giving us a gallery of characters with their own potentially-murderous motivations. Due to the speed in which Coppola wrote the screenplay, the identity of the murderer is easily deduced about halfway through the film– which doesn’t make for much in the way of suspense.

However, the pure excellence of Coppola’s craft, even at this early, low-budget stage, is undeniable. DEMENTIA 13 is absolutely the kind of film that shouldn’t hold up fifty years after its release, but there’s a small, palpable aura of prestige that lingers over it. Yes, it’s shlock, but it’s the kind of schlock you might find given a reverent release by the Criterion Collection.

Coppola’s camerawork is simplistic, belying the shoestring nature of the production. However, its minimalism draw inspiration from classical filmmaking techniques that give the film a timeless feel. This low-key approach amplifies the few stylistic flourishes peppered throughout; the opening high-angle shot looking down on a rowboat bobbing in the lake, as well as the floating, dreamlike nature of the underwater photography come to mind.

As lensed by Director of Photography Charles Hannawalt, the 35mm film image uses the low-budget necessity of the black-and-white format to its advantage. The contrast is crisp and moody, alternating between naturalistic and high-key lighting scenarios as needed. A vicious knifing sequence halfway through the film uses rapid-fire edits to create disorientation and a sheer sense of terror.

The homage is so apparent that it matches PYSCHO’s infamous shower murder scene shot-for-shot. This doesn’t read so much as Coppola trying to rip off Hitchock as it does as an example of Corman’s business model for deliberately emulating successful films in his cheap knock-offs. The same practice still exists today, most notably in “masterpieces” like SNAKES ON A TRAIN, churned out monthly by cheap production companies like The Asylum.

The music of DEMENTIA 13, provided by Ronald Stein, is appropriately gothic and mysterious. It’s traditional in that it’s composed like most orchestral scores of its day, but Coppola’s rebelliousness as a young filmmaker gets another chance to shine with the sly inclusion of diagetic rockabilly music. Using prerecorded source tracks may be commonplace in films now, but In the early 60’s, it was virtually unheard of.

The practice didn’t really gain steam until a generation of film brats like Coppola, George Lucas, Brian DePalma, and Martin Scorsese adopted it as an aesthetic trademark.

As a low-budget genre/exploitation film, DEMENTIA 13 doesn’t give us much in the way of a personal insight into Coppola’s psyche or development as a filmmaker. While it trades heavily in the tropes of schlock cinema, such as weak acting and easily-corrected inconsistencies (if the film takes place in Ireland, how come nobody is actually Irish?), it also carries a great deal of pathos and understated style.

It might seem dated by today’s standards, but I was surprised to find how effective DEMENTIA 13 was as an old school chiller. Its gothic iconography has considerable spooky charm, and it’s easily one of the better films within Corman’s extensive library. But most of all, it’s a solidly-constructed first effort from a blossoming filmmaker (who was still in film school, to boot) who was on the verge of shaking up the entire art form.

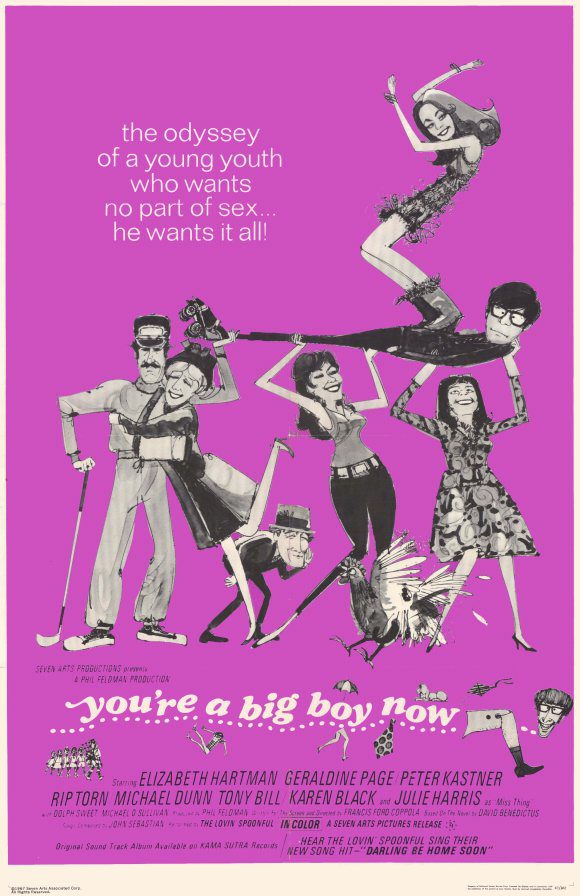

YOU’RE A BIG BOY NOW (1966)

It’s an inarguable fact that director Francis Ford Coppola benefited greatly from the nascent days of the film school institution. Making a film wasn’t as commonplace as it was now– back in the 60’s, your film was remarkable for the fact that you even made it.

Coppola was a different force altogether– before he had finished his master’s degree at UCLA, he already had the successfully-released features DEMENTIA 13 (1963) and BATTLE BEYOND THE SUN (1962) under his belt.

In order to graduate, Coppola needed to complete his master’s thesis film. Naturally, he crafted the most ambitious student film ever, a feat unmatched even by today’s standards. This effort was 1966’s YOU’RE A BIG BOY NOW, a feature adaptation of the David Benedictus novel.

Shot for the obscene sum of $800,000, Coppola’s little “student film” eventually premiered in competition at Cannes, secured distribution with Warner Brothers, and netted an Academy Award nomination for supporting actress Geraldine Page. If this were to happen to a student filmmaker today, he’d be hailed as the second coming of Christ– but for Coppola, this was only a taste of things to come.

YOU’RE A BIG BOY NOW tells the story of Bernard Chanticleer (Peter Kastner), a bookish, virginal young man who works in his father’s library in New York. HIs mother Margery (Geraldine Page), sets him up with an apartment in the city but aggressively warns him about the dangers and evils of women. Now living on his own for the first time, the sheltered young man’s eyes are opened to a whole world of sexuality and danger.

He begins dating the sweet Amy Partlett (Karen Black), but he quickly finds he can’t help himself when a beautiful, glamorous go-go dancer (Elizabeth Hartman) shows interest in him as well. Caught between Mrs. Right and Mrs. Right Now (I hate that I just wrote that), Bernard learns that there’s a lot more to love than sex.

The performances are appropriately outsized to match the comedic, absurd plot developments, but they also traffic heavily in a rebelliousness that lends the film a countercultural quality. The dynamics between the excitable Kastner and the seductive Hartman are well-drawn, if not a little cliche.

Kastner does an admirable job as the lead, delivering a performance reminiscent of Dustin Hoffman in THE GRADUATE (1967)– despite the fact that he had never seen it himself (THE GRADUATE was still a year away from release). Hartman’s character of Barbara Darling is distant and cold, completely unaware of the psychological damage she inflicts on her suitors. She fully embodies the weaponized sexuality that was an unintended product of the free love era.

Page’s Oscar-nominated performance is quite funny, if not entirely memorable. Her conviction that girls are the devil is a well-worn character trait, but she performs the role with a fresh urgency. Torn and Black would go on to have bigger careers after this film, so it’s incredibly interesting to see them as young upstarts here.

Torn is so young and fresh-faced that he’s nearly unrecognizable as Bernard’s stern, reserved father. Black does an admirable job embodying the kind of girl that a budding lothario knows he should pursue, even if that comes at the cost of a milquetoast characterization. While she’s innocent and sweet, she doesn’t judge Bernard for his transgressions, which is refreshing for her character’s archetype.

Bucking the trend of student films shooting on 16mm film, Coppola uses his considerable budget to film on 35mm. Andrew Laszlo, serving as Director of Photography, gives the film a fresh, energetic look that suits Coppola’s countercultural aesthetic.

The cold grays of New York City are contrasted with bright pops of color seen in the young characters’ attire and props. Indeed, all the adults are depicted in boring, neutral tones so as to make the teenagers’ vibrancy stand out. One great instance of this is the film’s opening shot, which starts wide on a dull, quiet library scene.

Suddenly, the camera rushes in towards the door, and Hartman’s character storms into the room. Clad in screaming orange and accompanied by the blasts of rock and roll music, her entrance signifies nothing less than the arrival of a new generation intent on upending the traditional order.

Editor Aram Avakian complements this attitude by employing fast-paced, experimental editing influenced by the then-burgeoning French New Wave. Other stylistic flourishes, like on-screen titles animated to resemble typewriting, further push the experimental tone that Coppola is after. As a result, the film must have felt very fresh and bleeding-edge in its techniques upon its release.

Robert Prince contributes a jaunty, energetic score, but the musical soul of the film belongs to rock band Loving Spoonful, which firmly roots the film in the teenage counterculture of the 60’s. It’s unpolished guitar riffs chafe against the edges of the frame, encroaching ever closer and eventually consuming its characters entirely.

YOU’RE A BIG BOY NOW finds Coppola combining his experience with his early softcore comedies with the hard-edged vitality of the emergent youth culture. The film’s tone is breezy and playful, with the kind of boundless optimism and curiosity reserved only for the young. There’s even a sense of burgeoning filmography to Coppola’s craft, manifested by the use of footage from DEMENTIA 13 as an art installation in a nightclub sequence.

By this point in his career, Coppola had yet to establish a consistent visual aesthetic, but his taste for experimentation and boundary-pushing is quite evident. With the release of YOU’RE A BIG BOY NOW, Coppola established himself at the forefront of his generation’s ascent into the industry. Not bad for a student film.

FINIAN’S RAINBOW (1968)

Full disclosure- I’m not a big fan of musicals. Something about people spontaneously bursting into song and dance makes me profoundly uncomfortable, and I can’t explain it. Naturally, I approached my viewing of FINIAN’S RAINBOW (1968), director Francis Ford Coppola’s third true feature film, with a large degree of hesitation.

While I don’t plan on watching it again, I have to admit it was much better and watchable than I expected it to be, thanks to young Coppola’s considerable storytelling ability and an evocative Southern setting. FINIAN’S RAINBOW, distributed by Warner Brothers, is Coppola’s first big studio picture, and the modest success of the film would further propel his career to new heights.

FINIAN’S RAINBOW is about Finian McLonergan (Fred Astaire) and his daughter Sharon (Petula Clark), who’ve recently left their native Ireland to venture to the mythical land of Rainbow Valley, Missitucky. Unbeknownst to Sharon, Finian is carrying a bag full of gold that he stole from a leprechaun named Og (Tommy Steele), and plans to place the gold in close proximity to Fort Knox so that it may multiply.

While Sharon falls in love with Rainbow Valley’s most eligible bachelor, Woody Mahoney (Don Francks), Og The Leprechaun tracks down Finian to Missitucky and attempts to take back his gold before he becomes mortal. Toss in a little song and dance, and a lot of Irish stereotypes and you’ve got the idea. It was by complete coincidence that I watched this very Irish film on St. Patrick’s Day, but my general amusement at that fact helped my enjoyment of the film overall.

Every member of the cast seems fully devoted to Coppola’s vision. Even the seasoned movie star and dancing legend Fred Astaire gives himself fully over to Coppla’s whims. Pushing 70 during the film’s production, FINIAN’S RAINBOW became Astaire’s last major movie musical. It’s a great send-off that allows Astaire to retain his youthful vigor, dazzling grin, and fancy-free footwork despite his elderly, frail state.

Clark garnered a great deal of acclaim for her singing talent as Irish lass Sharon McLonergan. Francks drew from the folk persona of Woody Guthrie for his portrayal of the rakish Mahoney. Keenan Wynn is a good sport, allowing himself to be humiliated at every turn as the film’s racist, lily-white antagonist, Senator Rawkins.

The sprightly Barbara Hancock plays Susan the Silent, who is unable to speak but communicates effortlessly via dance. As the cartoonish leprechaun Og, Tommy Steel received the bulk of ire directed at the film. His goofy, slapstick-laden performance was decidedly off-tone (despite the inherent whimsical nature of the story). I can’t say I blame his detractors– I hated that guy’s shit-eating grin, too.

FINIAN’S RAINBOW sees one of the largest casts that Coppola has ever assembled, and he does a great job filling out the population of Rainbow Valley with outsized, memorable personas. The expansive world-building on display proves to be a great training ground for the kind of epic filmmaking Coppola would take on in THE GODFATHER (1972) and APOCALYPSE NOW (1979).

Indeed, FINIAN’S RAINBOW marks a considerable uptick in scale and production value for Coppola, who makes great use of all the extra toys afforded him. The sunny, springtime exterior locales are given scope via extensive crane and dolly movements (and even the occasional helicopter shot), and all the set dressings required to sell his story are in abundant supply.

Curiously enough, Coppola mashes together location/exterior footage and sets made to look exterior with reckless abandon, oftentimes creating jarring transitions and leaps in logic. While some of these sets were built for valid reasons (lighting a forest at night would be too expensive), others seem to have little explanation.

However it does illuminate Coppola’s internal battle over shooting the film like a traditional Hollywood musical or indulging his experimental, more-realistic tendencies cultivated in film school. One instance of this indulgence is allowing specks of water to remain on the camera lens during a firefighting sequence, which gives the scene an immediate presence not unlike documentary.

While the film is decidedly old-school in its approach, an undercurrent of film brat rebellion charges the picture with a harder edge than it normally would have.

As lensed by Director of Photography Philip H. Lathrop, the 35mm film image– framed at the 2.35:1 widescreen aspect ratio– is heavily saturated with the gonzo hues of Technicolor and lit within an inch of its life. Coppola and Lathrop show an aptness for staging complicated group numbers with a breezy energy that draws the audience into being active participants in the song and dance.

The sleepy southern town of Rainbow Valley and its rich, brown/green color palette is fleshed out in great detail by production designer Hilyard M. Brown. Ray Heindorf rounds out the list of technical collaborators with his arrangement of the musical’s many numbers into jaunty, energetic orchestrations that retain a decidedly Irish influence.

Having been released in the prime days of the Civil Rights movement, FINIAN’S RAINBOW’s racial and cultural politics have now aged into amusing, quaint oddities. Its incorporation of actor Keenan Wynn playing blackface (having been magically transformed from white to black in the course of the story) was understandably met with controversy upon its release.

So many decades on, it still comes off as extremely politically incorrect, but is now more-easily written off as a product of antiquated cultural views. This is further reflected in the film with earnest, positive expressions about the benefits of credit, and even asbestos. Moments like these paint a fuller picture of an optimistic time gone by, albeit at the cost of losing a certain, timeless aura.

Coppola does an admiral job directing FINIAN’S RAINBOW, breezily clipping along the film’s 2 ½ hour running time so that it’s not a complete snoozefest. There are many positive things to recommend about it– Astaire’s performance, and the set design to name a few– as there are negative.

Its cultural legacy has since become its relevancy to Coppola’s development as a filmmaker. It was a huge step up for him, and the first real test of his talent. The sheer task of directing such a big, mainstream production would efficiently prepare Coppola for the biggest challenges of his career, and would allow him to soar like Astaire himself when lesser filmmakers would’ve fallen flat on their faces.

THE RAIN PEOPLE (1969)

A year after releasing his first big-budget studio film (1968’s FINIAN’S RAINBOW), director Francis Ford Coppola was back in theaters with a markedly different feature film. Channeling the experimental sensibilities and understated narratives of the French New Wave, 1969’s THE RAIN PEOPLE was a subtle, introspective road picture that eschewed all the frills of contemporary studio filmmaking.

For Coppola personally, the film is further notable in that it was the first project released under his fledgling production studio, American Zoetrope. In the years since, American Zoetrope has been a source of great trial and tribulation for Coppola and his associates, but has consistently delivered on its promise of making original, thought-provoking acts of cinema. As Zoetrope’s first feature release, THE RAIN PEOPLE is a fascinating window into the principles and ideals that shaped an upstart indie studio into a cinematic institution.

THE RAIN PEOPLE assumes the perspective of Natalie Ravenna, a lonely housewife who abruptly picks up and hits the road upon learning that she’s pregnant. Spurning her husband’s pleas to return home, she picks up a handsome, mentally stunted hitchhiker named Killer (James Caan). The two form an unlikely friendship, with Natalie becoming something of a caretaker to the young man.

Inevitably, Killer falls in love with Natalie, which doesn’t make their situation any easier when Natalie becomes romantically involved with a lonely police officer named Gordon (Robert Duvall).

Coppola’s command of his cast’s performances, especially in regards to their emotional restraint, is superb. Natalie, as played by Knight, is reserved and conflicted as she suddenly finds herself in the throes of a quarter-life crisis brought about by pregnancy. It’s a haunting performance, and Knight was rightfully recognized for the strength of her portrayal.

In hindsight, the most interesting aspect of Coppola’s casting is the first instance of collaboration with both James Caan and Robert Duvall. Everyone knows they’d both go on to legendary performances in Coppola’s next film, THE GODFATHER (1972), but not a lot of people know that Duvall and Caan were actually roommates at one point. If that doesn’t compel you to amicably figure out who’s taking care of those dishes in the sink tonight, I don’t know what will.

Caan is fresh-faced and quiet as Jimmy Kilgannon, affectionately nicknamed Killer. His character was a college football player who was left mentally stunted after a particularly bad concussion. He embodies a child-like innocence, with an unflagging loyalty and obedience to Natalie that’s not unlike a dog. Duvall, in contrast, is inquisitive and tough as a widowed cop looking for some rough love.

He’s dangerous and unpredictable, which makes him so attractive to Natalie in the first place. The battle between these two men is well built-up to, and when it finally explodes, it does so with the force of an atomic bomb.

What struck me most upon watching this film was Coppola’s visual treatment of the story. The picture, lensed by Director of Photography Wilmer Butler, is simple and unadorned. Coppola and Butler are content to let the 1.85:1 frame simply dwell on its subject, passively observing long, quiet moments of reflection and malaise.

The lighting is as naturalistic as the performances, and the air of realism hangs heavy over the proceedings. It’s almost the prototypical mumblecore film, what with its low-key look, simple performances and barely perceptible plot developments.

Ronald Stein, who previously supplied the score for Coppola’s DEMENTIA 13 (1963), creates a staccato, melancholy score here that also infuses a little bit of jazz into the rural West Virginian setting. Contrasting with the musical bombast that was FINIAN’S RAINBOW, Coppola adopts a reserved approach to music that matches his minimalist aesthetic. Even the film’s opening credits eschew music, opting instead for the quiet patter of early-morning rain and ambient clanking of garbage truck machinery in a quiet suburban neighborhood.

Curiously incongruent with the low-key nature of the photography, however, is Barry Malkin’s editing. Borrowing heavily from the innovations of the nascent wave of cinema rebels in France, Malkin incorporates a variety of avant-garde techniques like jump-cuts, poetic juxtaposition, mismatched sound cues, etc. Coppola and Malkin often pepper dialogue scenes with wordless flashes of perpendicular action, flashing forward or backwards to illuminate events that bring greater meaning to the dialogue sequence at hand.

The groundbreaking editing, when combined with the minimalist visual style, gives the film a very European vibe.

This points to a common, definitive trait of the “Film Brat” generation of directors– that of reference and/or allusion to classic works as well as the work of their contemporaries abroad. Unlike the directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age, directors like Coppola were part of a larger community of filmmakers inspiring each other in their attempts to redefine the language of cinema.

Coppola counts THE RAIN PEOPLE among the top five favorite films of his own making, and for good reason. It’s a strikingly confident work, free of the studio interference that would come to plague him as he became more successful. It was also his first collaboration with future STAR WARS creator George Lucas, who served as production associate on the film.

Filmmakers like Lucas were one of the reasons that Coppola founded American Zoetrope– he sought not only to advance his own cinematic interests, but to further the innovative spirit of filmmaking by empowering like-minded directors and giving them the resources to create outside of a stifling studio system.

Ironically enough, Coppola’s next film would beholden him to the studio system more so than he ever wanted (albeit at great benefit to his career). In that context, THE RAIN PEOPLE is an interesting look into an artistically pure Coppola, unfettered by outside opinions and influence, as he cements his particular brand of storytelling and characterization.

THE GODFATHER (1972)

What more is there to possibly say about 1972’s THE GODFATHER that hasn’t already been said? It is undoubtedly, inarguably one of the greatest films ever made. It’s a goddamn institution of cinema that dares you to find fault with it. Yes, you could say it’s overlong, convoluted, even boring– but by no means can you not respect it. I suspect that director Francis Ford Coppola had no idea what he was getting into when cameras first started rolling that fateful day in 1972.

Coppola initially took the job, not for passion, but for money. American Zoetrope, the company he founded with the intent to liberate himself from the studio system of filmmaking, found itself in debt to those very same studios due to budget overruns on his good friend George Lucas’ directorial debut, THX 1138 (1971). As the producer on that film, Coppola found himself deeply in debt and took on THE GODFATHER so that he could afford to feed his growing family.

It was precisely this familial element of the film’s genesis that threw the story into focus for Coppola. Paramount saw another cheap gangster film that would turn an easy profit, but Coppola saw a sprawling epic about loyalty, family, and honor that became a grand metaphor for the ruthless mechanics of American capitalism. So convinced of his own vision was he, Coppola endured a trial by fire wrought by studio executives who made very vocal their distaste of his casting and directorial choices at every step along the way.

It was the single most formative experience of Coppola’s career, even more so than his fiasco of a shoot in the jungle for APOCALYPSE NOW (1979).

We all know the characters, and we all know the story– to a varying degree, of course. THE GODFATHER’s famously labyrinthine plotting slowly reveals itself only through multiple viewings. By my own estimations, this was the the third or fourth time I’ve seen the film, but it was probably the first time where I was able to really follow what was going on throughout.

I also had the distinct pleasure of watching the film with my girlfriend (hi, Chelsea!), who was watching it for the first time. Many of the film’s sequences are iconic, but it was refreshing to see someone experience it for the first time, and still be actively engaged in a story that is nearly forty years old. This speaks to the great deal of timelessness that THE GODFATHER is imbued with– it’s truly a film that will endure through the ages.

THE GODFATHER focuses on the Corleone crime syndicate, a close-knit Sicilian-Italian family who have amassed a tremendous fortune through illegal gambling operations. As run by aging patriarch Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando), the Corleones are a well-oiled, efficient operation with friends in high places.

Set in New York in the decade following World War 2, THE GODFATHER chronicles the internal upheaval that the Corleones experience when pressure builds to join the increasingly-profitable narcotics trade, or risk losing their relevance in the world of organized crime. As a man of honor and principe, Vito is staunchly opposed to dealing drugs, which angers the heads of rival crime families.

An unsuccessful assassination attempt on Vito’s life sparks open warfare involving his sons, particularly Michael Corleone (Al Pacino), a war hero and the youngest of Vito’s progeny. When the heir apparent to Vito’s empire, hotheaded eldest son Sonny (James Caan) is betrayed by his brother-in-law and brutally gunned down in the street, and middle son Fredo (John Cazale) is deemed unfit to head the operation, Michael decides to assume control of the family. However, the cost of this decision will be his very soul.

The performances in THE GODFATHER are career-defining, and nothing short of legendary. A great deal of the film’s power comes from the sheer pathos and gravitas embodied by each and every character. This is all the more-remarkable due to the fact that the studio infamously hated the cast and fought to have some of the key players replaced.

Brando won the Best Actor Oscar for his role as Don Vito (and famously refused to accept it in order to call attention to the terrible depiction of Native Americans in cinema). Only 45 at the time of shooting, Brando assumed the affectations of a man twenty years his senior, all while under heavy prosthetic makeup and an elaborate jaw appliance that gave him a severe underbite. His heartbreak at the sight of his empire crumbling and the corruption of his sons is heartbreaking to watch, and makes his performance one of the most iconic in history.

Pacino’s portrayal of Michael Corleone became his career breakout and instantly established him as one of his generation’s top acting talents. Pacino’s Michael is vindictive and ruthless while still remaining likable, which makes for a believable performance as a man fated to become the very devil he meant to dispel. His character arc is one of the most compelling trajectories ever devised, and while it came close to a reality several times throughout production, it’s very hard to imagine anyone else other than Pacino in the role.

James Caan and Robert Duvall continue their collaboration with Coppola as Sonny and consigliere Tom Hagen, respectively. Caan is all fiery temper and braggadocio as the heir apparent to Vito’s criminal empire. Despite his presence in only 1/9 of the entire GODFATHER TRILOGY’s 9-hour running time, his presence hangs heavy over the entirety of it like a specter.

While Caan would continue delivering iconic performances throughout his career, his portrayal of Sonny Corleone will arguably be the one he is always remembered for. Same goes for Duvall, who as Vito’s adopted son of Irish and German descent, is one of the family’s most trusted outsiders. Acting publicly as the family’s lawyer, he privately takes on an advisor role to Vito, dispensing wisdom and objective reason.

Filling out the Corleone family is the inimitable Cazale in his film debut as middle son Fredo, as well as Coppola’s real-life sister Talia Shire as their sister Connie. While Cazale’s true importance lies in the events of THE GODFATHER PART II (1974), the roots of those problems are firmly established here by depicting Fredo as somewhat of a black sheep, too stupid and clumsy to reliably lead the Corleone family on his own.

Filling out the cast are Diane Keaton and Sterling Hayden as key players in the Corleone family saga. The impeccable Hayden plays Captain McCluskey, the repugnant, corrupt cop that Michael murders in cold blood. Keaton plays Kay Adams, who becomes Michael’s wife in the film.

Her anglo-saxon, WASP-y ways stand in stark contrast to the Corleone’s reserved familial identity, a dynamic visually reinforced by having her continually clad in bright primary colors that scream compared to the dark neutral shades that The Family dresses in. Her growing despair at the realization of Michael’s corruption is a focal point for the saga’s continuing conversation about ethics, and she becomes an avatar of sorts for our own arms-length distance from the family affairs.

Coppola finds an elegant way to visually depict this at the film’s end, when Kay stands outside the inner chamber of Michael’s office as his capos come to kiss his ring as the new Don Corleone. We see the remove from her perspective, and then Coppola elegantly cuts to the reverse shot– a close up of Kay’s falling expression as the door closes on her. The moment is pure cinema: the culmination of all that came before it and a charged beat that brings the film’s central conceit into clear focus.

The mastery of craft on display extends to the film’s cinematography, courtesy of Gordon Willis- a man who who’s ability to capture evocative shadows earned him the moniker “The Prince of Darkness”. Indeed, THE GODFATHER is a very dark experience visually and thematically. Shot on 35mm film, the image’s pervading darkness is broken only by strategically placed pools of light which create an exaggerated chiaroscuro without departing too far from reality.

Colors are washed out and desaturated, taking on a warm sepia tone that resembles a faded old family photograph. The darkly handsome 1.85:1 frame is given life by elegant, classical camera movements and deep focus that highlights well-worn, distinctive set dressing by production designer Dean Tavoularis. THE GODFATHER is often imitated and held up as a gold standard in cinematography, and after recent restoration efforts by Coppola himself, the film looks just as good as it did when it first unspooled on unsuspecting audiences forty years ago.

Any discussion of THE GODFATHER wouldn’t be complete with mentioning the film’s iconic musical theme. Composed by Nino Rota, the theme has ingrained itself into pop culture so much that it is instantly recognizable, even among those who haven’t seen the film. It’s a mournful waltz that effortlessly incorporates the major themes of the film into musical form.

The music is one of those serendipitous things that just resonates with the zeitgeist and becomes a part of the human experience– the mere mention of the words THE GODFATHER makes you immediately hear the song in the head (admit it, you’re humming it to yourself even now) . Part of why the films will never be forgotten is due to Rota’s score being so damn unforgettable. As for Coppola personally, it will accompany him in major milestones for the rest of his life– Oscar wins, public appearances, etc. I’d bet it’s even played at his funeral.

THE GODFATHER is a master-class in directing, revealing new insights upon each subsequent viewing. Many things, like Coppola’s inclusion of oranges in a given sequence as a bellwether of impending death are well known, but many more of THE GODFATHER’s secrets aren’t given up so easily.

Coppola’s rich explorations of the themes of family, loyalty, and obligation can be seen as explorations into his own cultural identity and heritage. For Coppola, and Italian culture at large, communal rituals, traditions and ceremonies are major life milestones by which the plot points of our lives are played out. The film begins with a lavish wedding steeped in Old World custom, designed to introduce us not only to this detailed world but to the complicated characters who inhabit it.

Conversely, Coppola ends the film with a baptism by both water and blood. It’s the most stunning sequence of the film, and arguably the single best contribution Coppola has ever made to the ever-evolving language of cinema: as Michael’s nephew and godson is baptized into the Catholic Church (and thus delivered into the proverbial saving grace of God), Michael’s capos carry out an elaborate series of murders designed to knock off the Corleones’ rivals and consolidate power in a baptism of blood (thus delivering Michael into the hands of Satan).

It’s a bone-chilling and haunting sequence, effortlessly orchestrated by Coppola in a way that takes full advantage of his experimental affectations. It literally created the cross-cut, a perpendicular editing technique that is still used to today to lend immense power to films like SKYFALL (2012) or THE DARK KNIGHT (2008).

Even Coppola’s contemporaries have referenced it, most notably in the Jedi extermination/creation of the Empire sequence in George Lucas’ STAR WARS EPISODE III: REVENGE OF THE SITH (2005). In this sequence in particular, THE GODFATHER’s hidden, double meaning as a title is revealed. While initially presented in assumed reference to Corleone patriarch Don Vito, it’s not until the end that we realize its in reference to Michael as he fully embraces his descent into evil.

THE GODFATHER has left an enduring legacy on the American psyche that’s almost unfathomable to comprehend. It was a bonafide phenomenon and instant classic upon its release, resulting in the highest box office returns and acclaim in Coppola’s career.

It catapulted him into the echelons of cinema’s great directors nearly overnight, and even though many of his contemporaries’ films have lost some of their luster upon reappraisal, THE GODFATHER still holds up as a sterling example of what cinema is and should be. It truly is one of the greatest films ever made, and anyone who thinks different is liable to find themselves sleeping with the fishes.

THE CONVERSATION (1974)

I have a strange, contentious relationship to director Francis Ford Coppola’s feature film THE CONVERSATION (1974). It is widely regarded amongst film circles as a masterpiece in its own right, and I tend to agree. However, there’s something intangible that I find alienating on a personal level. I don’t know what it is, so I can’t really explain it.

I had the same reaction the first time I saw the film in college– that of a deep, yet cold respect that left little in the way of actually loving it. I was hoping that this might change upon revisiting the film, but I can’t really say that it has.

After the Best Picture win for 1972’s THE GODFATHER, Coppola was awash in acclaim and could choose any project he wanted. Despite the calls to go right into production on a sequel to THE GODFATHER, Coppola chose instead to shoot a small, personal project as a palette cleanser.

This arguably began the trend of successful directors leveraging a blockbuster’s warm reception into making a passion project of their own design (a trend continued most recently by Christopher Nolan when he made 2010’s INCEPTION between the two final chapters of his DARK KNIGHT TRILOGY).

THE CONVERSATION concerns a private investigator named Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) who specializes in audio surveillance. He and a team of associates have been contracted to record a clandestine conversation between two seemingly-innocuous pedestrians in a crowded San Francisco park.

As Caul refines and mixes his recordings in his warehouse studio, the nature of the conversation reveals itself to be of murderous intent. Thinking he might be indirectly enabling a horrible crime to occur, Caul descends into an abyss of paranoia and mystery, convinced that he has become a target of surveillance himself.

The film was released just as the Watergate scandal broke, which made the story feel extremely relevant. The performances, which tapped into a fundamental distrust of authority figures, are striking without being over-the-top. As Caul, Gene Hackman eschewed his leading-man good looks by donning ill-fitting glasses and an unflattering plastic jacket that looks not unlike a placenta.

However, he injects a paranoid pathos that is utterly compelling, taking us along for the ride as he descends into madness. Caul might be one of the more intriguing protagonists in recent memory: his career consists of recording unsuspecting targets, but he has developed an extreme case of paranoia about his own privacy– even going so far as to tear up his entire apartment when he suspects it’s been bugged.

Coppola also enlists the help of GODFATHER alumnus John Cazale, who plays Stan, Caul’s bookish surveillance assistant. Out of the six films in which Cazale appeared during his lifetime, this is probably his smallest role, while also being his least neurotic/eccentric. Despite the limited screen time, Cazale brings a highly memorable presence to the film.

It really is a shame that we lost Cazale so early, as he might have been one of cinema’s most treasured character actors.

Rounding out the cast is Allen Garfield, Cindy Williams, Harrison Ford, and recurring Coppola collaborator Robert Duvall. Garfield plays Bernie Moran, a sound surveillance expert from New York and a friendly rival of Caul’s. Williams plays Ann, the anxious, vulnerable woman at the center of Caul’s surveillance. Ford, who was introduced to Coppola via George Lucas’ AMERICAN GRAFFITI (1973), plays Martin Stelt, a well-dressed businessman who stalks Caul in pursuit of his recordings.

It’s interesting to watch Ford in his pre-Han Solo days, as his developing talents are very noticeable. He’s not particularly good in THE CONVERSATION, but you can tell the potential is there. Meanwhile, Duvall appears in somewhat of a glorified cameo as the mystery man who commissions Haul to record the targets, only to find himself a victim of his own suspicions.

THE CONVERSATION has a much more even look compared to the amber-soaked visuals of THE GODFATHER. Originally lensed by director of photography Haskell Wexler, Wexler proved to be combative with Coppola and was replaced by Bill Butler, Coppola’s DP from THE RAIN PEOPLE (1969). The 1.85:1 35mm film frame is appropriately gritty and seedy, dealing in a bland color palette of grays and neutrals.

This color scheme is further reflected by Dean Tavoularis’ production design, which features cold, brutalist architecture at odds with its picturesque San Francisco setting. Perhaps this is why I feel so alienated by the film– a great deal of the film’s story takes places in cold, imposing locales that blot out clarity and logic. While opting for a relatively realistic presentation, Coppola does include an impressionistic dream sequence rendered in a cobalt blue through a thick layer of smoke.

Despite the unassuming visual presentation, Coppola makes artful use of his camerawork in a way that reinforces the story’s central themes. A recurring visual motif is “machinery in motion”, most notably seen in the whirring gears of Caul’s audio equipment. Telephoto lenses prove to be a boon to Coppola’s aesthetic, giving the film’s surveillance sequences a verite feel that’s highly effective.

The opening shot (a slow zoom-in from a bird’s-eye perspective that finds a single conversation amongst a crowd of people) is one of the most famous of its kind, praised for its virtuoso sound editing by legendary cutter Walter Murch.

The camera movements are mostly restricted to the functional movement of actual surveillance cameras (the ending shot that pans back and forth is the clearest example). This is an inspired move from Coppola, and yet another example of how he has redefined the visual language of cinema throughout his career to better tell his stories.

THE CONVERSATION utilizes the jazzy piano work of David Shire for its score, which combines the sounds of swing and ragtime music with minor keys that suggest intrigue and mystery with sinister underpinnings. While it may seem odd for such a low-key, paranoid film, the sound reflects Caul’s own musical inclinations– he’s seen throughout the film playing his saxophone along to jazz records when he’s alone in his apartment.

For the entirety of the 1970’s, Coppola found himself on a directing hot streak in which he could do no wrong. THE CONVERSATION falls somewhere in the middle of this streak, and sees Coppola embracing the low-key aesthetics of his independent roots while applying them to the trappings of a big-budget genre picture.

Coppola looked to his filmmaking peers abroad for inspiration when crafting the film, a practice that would come to define the film school-bred directors of his generation. His chief influence was Michelangelo Antonioni’s Italian hit, BLOW-UP (1966), which featured a similar plot of using recordings (photographs in Antonioni’s film) to uncover a murderous conspiracy.

It could also be argued that Akira Kurosawa’s RASHOMON (1950) was another big inspiration to Coppola, with its multilayered narrative featuring different interpretations of a single event. These European sensibilities lend at once both a worldliness as well as a bracing sense of innovation to what was somewhat of a stale period of American filmmaking.

THE CONVERSATION went on to snag the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, and has since joined the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress, thereby stitching itself into the very fabric of American culture. Coppola himself has stated that THE CONVERSATION is his favorite film of his own, owing to the very personal nature of the story. For Coppola’s production studio, American Zoetrope, the film’s success was a validation of everything he had set out to do with its creation.

By tackling a smaller, radically different film after the success of THE GODFATHER, Coppola bought time to creatively refresh himself before embarking on production of THE GODFATHER PART II that very same year. THE CONVERSATION has aged remarkably well since its release, becoming a classic in its own right. While I still found myself inexplicably put-off by its subdued charm, I can’t deny the film’s sheer excellence that has contributed to its longevity. THE CONVERSATION still has many secrets to tell us… all we have to do is listen.

THE GODFATHER PART II (1974)

As a general rule, sequels are pale imitations of the original films whose stories they continue. In the modern Hollywood climate where franchised properties rule supreme (and nine out of ten films are a sequel, prequel or remake), it’s almost unfathomable to think of a time when sequels were looked down upon with disdain.

It would take nothing less than the man who single-handedly re-energized American cinema to make a sequel that stood on equal footing with its predecessor and usher in the age of the serial film franchise. Released in 1974, director Francis Ford Coppola’s THE GODFATHER PART II undoubtedly (and ironically) became the genesis for today’s serialized cinematic landscape.

There is considerable discussion as to which is the superior film, with a substantial camp proclaiming THE GODFATHER PART II as not only superior to the 1972 original, but one of the greatest films of all time. Personally, I fall into this mode of thought as I find THE GODFATHER PART II to be a richer exploration of the themes of loyalty and succession that so brazenly defined THE GODFATHER.

The film marks a substantial expansion in scope and vision for Coppola, who enjoyed abundant resources and minimal studio intrusion during the shoot due to the runaway success of the original film. As such, THE GODFATHER PART II is arguably Coppola’s biggest, most-fully-realized film– and undoubtedly his best.

Picking up right where the first film left off, THE GODFATHER PART II finds the Corleone family thriving in their adopted home of Lake Tahoe, Nevada. On the occasion of Michael’s eldest child receiving his first communion, interfamilial conflict is brewing anew.

The new leader of Clemenza’s spinoff caporegime, Frankie Pentangeli (Michael Gazzo), comes to Michael (Al Pacino) requesting his help in resolving a dispute with the NY-based Rosato brothers. Michael refuses, citing a conflict of interests with the Rosato brothers’ employer, a Florida-based Jewish gangster Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg.

That night, an unsuccessful assassination attempt is made on Michael’s life, throwing the Corleone compound into chaos. Michael travels to see Roth in Havana on the eve of the Cuban revolution, whilst trying to figure out who betrayed his family. As the truth becomes evident that the betrayal rests inside his innermost circle of trusted advisors, Michael must sink to an unprecedented level of darkness to consolidate his power, even if it comes at the cost of his own family.

Meanwhile, a parallel narrative runs side by side Michael’s 1958 storyline. This alternate story takes place in New York City’s Little Italy during the early twentieth century, as a young Vito Corleone (Robert DeNiro) rises to become the all-powerful Don Corleone introduced to us in THE GODFATHER. Arriving in Ellis Island as a child refugee from his hometown of Corleone, Sicily, Vito adapts well to his community’s particular brand of American capitalism.

The major milestones of Vito’s life are presented in comparison with Michael’s own tyrannical reign, which creates nothing less than the grand American Epic in its chronicle of power and destiny.

Chances are if you ask any professional actor about their reaction to THE GODFATHER series, they will gush at length about their love of the performances. The series boasts one of the most unexpectedly impeccable casts of all time, and THE GODFATHER II resulted in no less than five acting nominations at that year’s Academy Awards. Of those five (Pacino, DeNiro, Talia Shire, Lee Strasberg, Michael Gazzo), only DeNiro walked away with a golden statue, but that doesn’t mean any of the other performances are less distinguished.

THE GODFATHER PART II is Pacino’s show, showcasing his total embrace of moral bankruptcy and fundamental distaste for the necessity of his sins. It’s a tour de force performance, embodied by a quiet, haunting intensity that lingers on a fundamental level.

DeNiro, an unknown whom Coppola cast after remembering his strong audition for the original film, is impeccable as the young Vito, channeling all of the physicality that Marlon Brando made famous while giving it the vigor and virility of a young man. DeNiro’s Vito is the strong, silent type– a family man with vision and honor that could easily become a feared criminal leader.

The role was DeNiro’s breakout performance among mainstream American audiences (he had previously made a splash as Johnny Boy in Martin Scorsese’s MEAN STREETS a year prior), and was a stunning first act to one of the most acclaimed careers in cinema. The presence of young Vito makes the entire GODFATHER saga richer and is the best manifestation of Coppola’s exploration of what it means, to quote those infamous opening lines to the original, to “believe in America”.

The supporting cast is just as compelling as the marquee talent, helped largely by the considerable investment audiences made in their emotional arcs during the first film. Diane Keaton reprises her role as Michael’s wife, Kay, continuing her trajectory as a disenfranchised wife who finds she must do the unthinkable in order to truly hurt him as much as he’s hurt her.

Regular Coppola collaborator Robert Duvall’s reprisal of consigliere Tom Hagen is also given added responsibility this time around as a reluctant accomplice to Michael’s nefarious aims.

John Cazale returns as Fredo, playing a much larger role in the Corleone’s Shakespearean drama as the older brother who’s upset over being passed over. Cazale’s performance in this film is easily his career-best, imbued with a seething resentment stemming from his incompetence. As I’ve written before, Cazale was only with us as an actor for a very short time.

He only made six films before suffering a premature death, but what impeccable films those six were (the two GODFATHERS, Coppola’s THE CONVERSATION (1974), Michael Cimino’s THE DEER HUNTER (1978), and Sydney Lumet’s DOG DAY AFTERNOON (1975)). Cazale is heartbreaking here in that his actions lead to very tragic consequences, even though he’s just trying to earn a little respect. Cazale will always be synonymous with his depiction of Fredo Corleone, and it’s a shame he was never formally recognized for his subtle, excellent performance.

Talia Shire returns as Connie, who has fallen into bouts of deep depression and ill-advised relationships with men Michael doesn’t approve of, all as a way to get back at him for having her first husband murdered. No longer the hysterical, tearful woman that she was in the first film, the Connie found in THE GODFATHER PART II is refined and elegant, taking her first steps on the path to becoming the Corleone matriarch after her mother’s passing.

A gathering of new faces breathe fresh blood and dramatically-rich conflict into the series, most notably Lee Strassberg and Michael Gazzo. As the wizened Jewish gangster Hyman Roth, Strassberg was lured out of retirement to craft an unforgettable character who’s frailty belies a lethal menace. Initially presented as somewhat of a buffoon, Gazzo’s Frankie Pentangeli is an unexpected, conflicted antagonist to the Corleones whose actions cause key members of the Corleone family to question their own motivations.

Surprisingly, a young Harry Dean Stanton pops up as Frankie’s bodyguard, who I had never noticed in the film during previous viewings. And last, but not least, James Caan famously received his entire pay from the first GODFATHER for his one day shoot reprising Sonny Corleone for a flashback sequence at the end of the film. The balls on that guy, but credit is due since he actually pulled it off.

One of the defining traits of THE GODFATHER series is that all the films visually resemble each other. When taken together, all three films coalesce to form a single, nine hour magnum opus. This is due in large part to Director of Photography Gordon Willis, who devised THE GODFATHER’s striking visual look and replicated it in subsequent installments.

The 1.85:1 frame, shot on 35mm film, is rich in darkness, continuing the sepia-tinged aesthetic established in the first film. The increased budget means more resources, which Coppola uses to great effect to expand the scope of his story with sweeping, operatic camera moves and a heavily detailed period recreation by production designer Dean Tavoularis.

One interesting thing that Willis does to help differentiate the two time periods can be found in the 1917 sequences, where sunlight is depicted in interior sequences as an intense glow that gives a distinct halo to characters when they stand in front of windows. This approach subtly recreates the evolving nature of photography at the turn of the century, where greater degrees of latitude had yet to be developed and there was a much harsher contrast between light and dark.

Composer Nino Rota returns with his mournful, elegiac waltz of a score that has lingered in our collective consciousness for decades. With THE GODFATHER PART II, he builds upon themes and leitmotifs that show the progression of Mario Puzo’s beloved characters and to reflect their growing inner turmoil as the stakes stack ever-higher.

Coppola also includes a variety of diagetic source cues that paint a bigger picture of the Italian culture at large. This is most notable in the Fest of San Gennaro sequence (which I’ll discuss at length later), which uses the fascistic Old World sound of “Marcia Religioso” to astounding effect.

Put simply, THE GODFATHER PART II is a staggering accomplishment of directorial prowess. That Coppola reached this level of skill so early on in his career is astounding. While many sequels fail in their rush to rehash the story beats that worked in the original, Coppola’s original vision for THE GODFATHER was so strong and compelling that, when given carte blanche to do as he pleased, the subject matter yielded entirely new, unexpected and shocking ways for the story to continue.

Many casual filmgoers don’t know this, but while the original film was based off of Mario Puzo’s novel, there was never an accompanying sequel novel off which to base a film version. The entire story of the Corleones in midcentury Lake Tahoe (and their presence during the Cuban revolution) are entirely new fabrications devised by Coppola himself, albeit with some help from co-writer Puzo. The Little Italy sequences set in 1917 are derived from a single chapter in Puzo’s original novel, yet fleshed out in a way that contrasts Michael’s fall from grace with Vito’s rise to power.

Indeed, this parallel rendering of a father and son at the same point in their lives during different time periods is one of the most affecting and relatable aspects of the film, and an unprecedented, inspired move on Coppola’s part. As a young man myself, trying to establish my career and rise up to become whatever person I’m meant to be, I often find myself reflecting on how my own father came to be the person that I now look upon as a leader in his community and a model of manhood and success.

Obviously, he didn’t shoot people or join organized crime to get where he is, but the pursuit of the American Dream is something that everyone can relate and aspire to, regardless of their trade. So naturally, I respond on a profound level to this kind of portraiture that Coppola has developed.

There’s one scene in particular I’d like to highlight as profoundly effective on me as a filmmaker, while also being a master-grade illustration of what just might be the perfect cinematic sequence. Succession and ascendance into power are primary themes in the trilogy, with an act of murder usually serving as the initiation into the upper echelons.

In THE GODFATHER, this is shown when Michael murders Salazzo and Captain McCluskey at a quiet Italian restaurant. In THE GODFATHER PART II, we witness young Vito’s own baptism of blood, which takes place during the famous San Gennaro street festival in Little Italy. Vito stalks the rooftops above the celebration, following the movements of his target: Don Fanucci, a wealthy gangster who’s been oppressing and intimidating the community. The soaring brass of “Marcia Religioso” serves as a quasi-fascistic accompaniment to the proceedings and lifts it to the level of opera.

If THE GODFATHER is about rising to power via succession, then THE GODFATHER PART II– with its inclusion of this sequence and the Cuban revolution storyline– is about taking power by force. Coppola’s sequel is about the deposition of kings, and how delicate that power is to hold onto once achieved. The San Genarro sequence itself is perfectly paced, with nary a single shot wasted.

Each detail and moment is precisely calculated to generate suspense: from Vito’s prolonged stalking, to his manipulation of the lightbulb, to the use of a towel to dampen the sound of his gunfire, to Don Fanucci’s stunned reaction to the messy, imperfect red button that’s been punched haphazardly into his cheek and through his brain. As far as the construction of a sequence goes, it’s perfect. Coppola earned his first Oscar for directing with THE GODFATHER PART II, arguably in large part to this simple, yet riveting sequence.

Due to the relative freedom he enjoyed making the film, THE GODFATHER PART II is a view into Coppola at his most unfiltered. As his own family was growing and he bought an estate out in Napa, CA to house them, he channeled the insights learned from these life experiences into his depiction of the Corleone family. The story is a deeper exploration of the customs and culture of his ancestral heritage, which yields some of the most memorable and dramatically-rich plot developments in cinematic history. Furthermore, the story requires Coppola to run a production on a personally unprecedented scale, especially in the young Vito Corleone sequences. For a filmmaker who’s start was in small-budget schlock films (indeed, Coppola’s old boss Roger Corman makes a cameo appearance in the Senate Committee scenes), Coppola rises to the considerable challenge with bold vision and an effortless grace.

Objectively speaking, this is the pinnacle of Coppola’s career as a filmmaker. It was met with a huge box office take, but ironically had a modest critical reception that only grew as people had a time to reflect on it. This proved to be beneficial as THE GODFATHER PART II swept that year Academy’s Awards, netting gold statues for Best Art Direction (Tavoularis), Best Score (Rota), Best Adapted Screenplay (Coppola & Puzo), Best Supporting Actor (DeNiro), a repeat Director (Coppola), and Best Picture.

All the more astounding for the fact that it was a sequel (and one that started the trend of including numbers in the title to boot), THE GODFATHER PART II became a phenomenon that cemented the series’ place in pop culture and cinematic history. Furthermore, the Library of Congress deemed it significant and worth preserving in 1993 when it inducted the film into the National Film Registry.

A film can’t get any more successful than that. Even though his recent output has been somewhat weak, Coppola remains at the top of the heap of respected auteurs precisely because of the lasting fallout from this film. THE GODFATHER PART II is a cornerstone in the house that cinema built, and it will endure long after its makers are gone.

APOCALYPSE NOW (1979)

Some films are to be cursed from their very inception. They taunt their makers with Herculean obstacles, only to break their spirits when they fall far short of their goals. Some of these filmmakers would never recover (like Michael Cimino and 1980’s HEAVEN’S GATE), their careers never again retaining the same heady heights as their previous successes.

A select few manage to overcome these soul-crushing challenges, and fewer still actually manage to make a truly transcendent piece of work. No film’s making more embodies the term “fiasco” than director Francis Ford Coppola’s passion project APOCALYPSE NOW (1979). Shot as the follow-up to the unfathomably successful THE GODFATHER PART II (1974), Coppola suddenly found himself in those most treacherous of directorial waters: complete financial freedom.

The production of APOCALYPSE NOW, which dragged on for close to three years, most certainly took many years off of Coppola’s life (as well as hundreds of pounds). However, this sacrificial (and literal) pound of flesh netted him something much more valuable: immortality, in the form of one of the greatest and culturally significant films of all time.

APOCALYPSE NOW is nothing less than a cinematic descent into madness. Based off Joseph Conrad’s lurid novella HEART OF DARKNESS, Coppola and screenwriter John Milius have kept the basic plot conceits while updating the setting from a turn-of-the-century Congo River to the Vietnam War.

Initially developed to be a directing vehicle for Coppola’s American Zoetrope colleague George Lucas, Coppola took the helm after Lucas departed to make 1977’s STAR WARS (a move which insulted Coppola so much they didn’t speak for years). Coppola’s vision was to paint the Vietnam War as it truly was– a psychedelic, deeply disturbing voyage into the darkest corners of men’s souls. Coppola aimed to make the greatest film ever created; an allegory for the entire American experience in Vietnam. It’s safe to say that he more or less succeeded, despite the infamously-troubled production nearly killing him.

APOCALYPSE NOW tells the story of Willard (Martin Sheen), a burnt-out Army captain who’s sent out on a confidential mission: find and execute a rogue Colonel, Walter E. Kurtz (Marlon Brando) who’s gone insane and established his own kingdom of brutality in the upriver jungles of Cambodia.

To transport him up the river, Willard is assigned a patrol boat operated by a small team of Naval officers. As they inch ever closer to Kurtz’s savage compound, the men endure the hells and existential crises of the Vietnam War that rages around them. When they finally arrive, Willard experiences a strange emotional connection to Kurtz’s deranged dogma that threatens to foil his mission and consume his sanity.

The film is a staggering achievement on all fronts. As to be expected from Coppola, the cast is exemplary, with many turning in career-defining work despite the brutal filming conditions. Martin Sheen, who replaced original actor Harvey Keitel two weeks into production, gives one of the best performances of his career as Captain Willard.

We first meet Willard as a strung-out husk of a man, rotting away in his hotel room in wait for an assignment that may never come. Sheen’s haunting voiceover provides a dark, interior perspective to the events of the film, helping us to understand his psychological connection to Kurtz.

Sheen gives all of himself over to his character, even to the point where he infamously suffered a heart attack at the age of 36 as a result of the stress he endured during production. With his haunting performance, Sheen seared himself into our collective consciousness and became an avatar for the American experience in Vietnam.

Marlon Brando, despite only having a few minutes of actual screen time, easily earns his top billing by ominously towering over the story as the near-mythical Col. Kurtz. Coppola managed to lure the reclusive star into the jungle for one more collaboration, but Brando certainly didn’t make it easy for his exhausted director. Famously, Brando not only showed up (late) to set overweight and bald, but having not read the screenplay or Conrad’s original novel.

Brando battled Coppola on every single element of his character, but given the unfathomable genius of Brando’s performance, it’s easy to see there was a method to his madness. Coppola shot Brando in shadows and close-ups mainly as a way to hide his enormous girth, but in doing so, he created a staggering personification of unknowable evil.

Of his late career roles, Brando’s performance as Col. Kurtz eclipses even that of Vito Corleone in Coppola’s THE GODFATHER. While he would go on to do a handful of roles in smaller films until his death, APOCALYPSE NOW marks Brando’s last great appearance in cinema, closing the book on one of the medium’s most talented personas with a pitch black conclusion.

Robert Duvall, who by this point had appeared in every Coppola film since 1969’s THE RAIN PEOPLE, channels a very different kind of unhinged psychopath in the form of Lt. Colonel Bill Kilgore. Duvall’s Kilgore heads the 9th Air Cavalry Regiment, a cocksure squad of gung-ho helicopter jockeys who tear ass across the jungle while blasting Wagner’s “Ride of The Valkyries”.

Representing the testosterone-laden braggadocio that led us into the Vietnam War in the first place, Kilgore barks each line with a forceful authority. His eyes obscured behind pitch-black sunglasses, Kilgore’s specialized brand of cowboy diplomacy leaves nothing but fire and death in its wake. His lust for war is matched only by his love of surfing, which he manages to pack in even under heavy artillery fire.

Duvall clearly enjoys the chance to chew scenery, which he doesn’t usually get to do under Coppola’s direction. Despite a comparable screen time to Brando, Duvall’s performance is highly memorable due to his pathological delivery of enduring lines as “I love the smell of napalm in the morning”. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was the only one on the entire production who actually had any fun.

Accompanying Sheen on his journey upriver are the colorful characters of the PBR boat, manned by the gruff quartermaster George Philips (Albert Hall). The late Sam Bottoms appears as Lance, a boyish California surfer whose clean-cut persona descends into a druggy haze as he tries to cope with the horrors of the war.

A young Laurence Fishburne (only 14 at the time) plays Mr. Clean, a cocky kid whose self-deceit over his own mortality will be his ruin. Finally there’s Frederic Forrest, who previously appeared in Coppola’s THE CONVERSATION (1974). Forrest plays Chef, a mustachioed saucier from New Orleans and an unpredictable, manic presence. These characters help to establish levity and companionship as the circumstances grow more dire.

Rounding out the cast are Dennis Hopper, Harrison Ford, and G.D. Spradlin. Hopper plays The Photojournalist, the strung-out jester of Kurtz’s court. Hopper adds a great deal of energy late into the film, drawing on his hippie persona that he established ten years earlier in EASY RIDER while taking it to a dark extreme.

A pre-STAR WARS Ford, having previously appeared in THE CONVERSATION for Coppola, plays Col. Lucas, a bookish officer who briefs Willard on the mission. Spradlin, who played Senator Geary in THE GODFATHER PART II, plays the general that gives Willard his assignment.

To create APOCALYPSE NOW’s acid-baked look, Coppola turned to Director of Photography Vittorio Storaro. Filmed on 35mm film, Coppola and Storaro take advantage of the panoramic 2.35:1 aspect ratio to capture Vietnam’s nightmarish vistas. A palette of saturated earth tones and yellow highlights gives a sweaty, slightly sick look to the visuals.

This burnt-out look is further complemented by the use of lens flares and relentlessly plodding camerawork. Coppola utilizes a great deal of aerial photography to give an uneasy majesty to the proceedings, capturing Dean Tavoularis’ exhaustive production design in all its sprawling glory. The editors (Walter Murch, Lisa Fruchtman, and Gerald B. Greenberg) make recurring use of crossfade transitions and double-exposed/layered shots that give the film the surreal aura of a bad acid trip. APOCALYPSE NOW is easily Coppola’s most visually stylized film apart from 1992’s BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA, accentuating the psychedelic, nightmarish nature of Vietnam.

Sound plays an enormous part in Coppola’s grand vision, beginning with its pioneering use of the Dolby 5.1 Surround sound system– which has since become the exhibition standard for all major films. APOCALYPSE NOW paints a sonic portrait of Vietnam even more hellish than its imagery, punctuated by concussive bomb blasts and the menacing drone of helicopter rotors.

Coppola’s vision for a psychedelic experience extends to the sound design, where he synthesized many sound effects so as to be indistinguishable from the score (the helicopter droning being the most famous example). Continuing his penchant for collaborating with family members, Coppola enlists the help of his father Carmine to craft the score.

Coppola the elder creates a foreboding electronic score that uses discordant tones to create a fundamental unease and an encroaching sense of malice. Francis Coppola also utilizes the druggy sound of The Doors and The Rolling Stones to further establish the psychedelic aspects of his vision.

It’s a big feat when a filmmaker is able to indelibly link a pre-existing song to a film so strongly that they become inseparable. The auteurs rising up amongst the Film Brat generation realized the power of well-placed music, not the least of whom was Coppola himself. With APOCALYPSE NOW, Coppola creates several such such moments as easily as you would tie your shoe.

There’s the brooding vocals of Jim Morrison’s “This Is The End” playing over silent footage of napalm reducing an entire jungle to cinders, or the unforgettable “Ride Of The Valkyries” sequence (which was referenced later in Sam Mendes’ JARHEAD (2005) as a way to pump up young Marines on the eve of their deployment to Kuwait). There’s even Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Susie Q”, which accompanies the appearance of three dancing Playmates during a rowdy USO show. I can’t think of another film that so brilliantly and creatively mixes sound and music to such striking effect.

Coppola’s habit for experimentation with the language of cinema is on full display with APOCALYPSE NOW. He paints Willard’s journey upriver as an allegory for a journey backwards in time, beginning with the machine-based warfare of the present and reaching back to the primitive, sacrificial nature of tribe-based social systems.

He also released the film without titles or credits, originally intending to tour the film around the country with printed programs. While this didn’t exactly come to pass, most home video releases of the film omit credits, making for a fully immersive descent into madness free from conventional cinematic constructs.

In a rare move, Coppola appears in a cameo as a newsreel director who yells “pretend you’re fighting!” to soldiers as they run by his camera. This is, of course, an allusion to the manufactured image that the television/entertainment complex depicted the war with, but it also goes a long way towards establishing the story’s startlingly self-aware viewpoint.

The Vietnam War was the first major war to be beamed directly into our households via television, and Coppola gracefully touches on the point while making a concise point about the media’s perversion of combat.

The story of APOCALYPSE NOW’s production has been extensively documented in print and film (most notably in wife Eleanor Coppola’s brilliant HEARTS OF DARKNESS documentary), so I won’t go into too much detail. It was (and still is) the biggest production Coppola has ever mounted, with a scale and scope so staggeringly massive that one film could barely contain it all.

THE ODYSSEY-like nature of the story required an equally operatic point of view, which Coppola was well-equipped to handle due to his previous experiences. What he wasn’t equipped for, however, were the almost-biblical challenges he had to face with shooting the film in the primordial jungles of the Phillippines.

Before he even could get a firm handle on his operation, the production ballooned millions of dollars over-budget and months behind schedule. A six-week shoot turned into almost thirty, and the tempestuous tropical climate wreaked havoc on expensive sets as well as morale. Coppola found himself shouldering nearly all of the burden alone, losing nearly 100 pounds during the process. Simply put, the shoot was hell. The fact that such a great film, let alone a coherent film, emerged from the wreckage is nothing short of a miracle.